1 What Are the Key Concepts?

Success in learning a second language depends, naturally, on exposure to the language. We need very extensive experience, and we need to “take in” what we experience. But the human mind is not a recording device, passively absorbing whatever it encounters. It is, rather, a complex information processor, using its own principles and knowledge to make sense of the things “out there” – things like instances of language – and adjusting its knowledge accordingly. Thus, a central topic in second language acquisition (SLA), and perhaps the central topic, is how the human mind deals with the language around us. It is the topic of input.

As a major research area, this topic is naturally rich in terminology. In presenting this terminology, I will begin with some terms that are not directly about input but are always present in the background and so deserve some consideration. This is followed by an extended discussion of “input” itself, after which I will consider more specific concepts related to input, some from the study of the mind and others primarily related to teaching.

1.1 Some Background Terms

A key background term that is typically left in the background is language. It can be defined in many different ways, from many different perspectives. Perhaps the most important dividing line falls between cognitive and social/cultural perspectives. Language can be seen as something in an individual’s head or it can be seen as a feature of social relations and the cultures within which they are embedded. It is undeniably both and therefore can be and must be studied from both perspectives, with the ultimate goal of establishing a unified explanation.

The concept of input belongs primarily to the cognitive side of this divide.Footnote 1 Cognitive theory owes a great deal to the computer metaphor, seeing the mind as an information processor. It receives information through the senses, processes and stores the information, retrieves that information when needed, and uses it to produce output in the form of actions, including speech. In this metaphor, input is the information taken in by the computer, or perhaps the process of taking it in. The nature of this “taking-in” process represents the fundamental issue for the study of input.

From a cognitive perspective, looking at what is inside our heads, language is the interaction among a number of distinct types of knowledge and ability. These types include, at least, phonological (linguistic sounds), morphological (the structure of words), syntactic (the ways that phrases and sentences are constructed), semantic (the meanings of linguistic units), pragmatic (meaning in social context), articulatory (the muscle movements that produce speech), and orthographic (written forms). This non-monolithic character of language will assume some importance in Section 4.

A second language shares this character, as it also includes sounds, structured sentences, meanings, and physical control of speech. The cognitive conception of a second language is well captured in the term interlanguage (Reference SelinkerSelinker, 1972). It refers to the knowledge of L2 learners, which is to say the state of their underlying linguistic system at any given point. The term has the advantage of being theory neutral, its main claim being simply that there is a system, not just scraps of information or modifications of the first language. To the extent that a given learner can use the language fluently and competently, the interlanguage is what makes this use possible.

The nature of the system has always been a source of dispute, and ideas have shifted over the years (see Reference Tarone, Han and TaroneTarone, 2014, for a useful summary). Contrary to Reference SelinkerSelinker’s (1972) original conception, interlanguage has generally come to be seen as a genuine language. Partly for this reason, universal grammar (UG) theorists (see 2.6) have embraced the concept, as it fits well with their overall conception of second language and second language learning and provides a useful way to frame major issues. The dynamic nature of the system has also come to the fore, though the details are again a theoretical issue. One important aspect is variability – not just over time, but also from one context or task to another. Research, from various perspectives, has also been dedicated to the discovery of more or less predictable ways in which interlanguage develops, on its own terms, not simply reflecting the character of the L1 or the target language. The L1 was originally given a prominent position. This role was subsequently challenged, but now it is once more recognized as a significant factor, though theoretical divergence occurs on exactly how it affects the interlanguage. Not withstanding the many disagreements, the idea of interlanguage as a developing system has become a key part of SLA and is likely to remain so.

If the interlanguage is a system, what about language-related knowledge that is not an integral part of that system? Such knowledge clearly does exist. An English learner who has been taught a given grammar rule might never manage to incorporate that rule in the interlanguage or use it in speech or writing but still be aware of it and be able to talk about it. A Mandarin learner who has little or no ability to produce the tones of the language or hear them in speech might still know that the language has four tones and be able to accurately describe them. Linguistics students may have mastered concepts like the Theta Criterion or feature interpretability, but it is unlikely that this knowledge will ever become part of their interlanguage for any second language they are learning.

This language-related knowledge has been referred to with a variety of terms, with somewhat varying meanings, notably including metalinguistic knowledge, knowledge about language (as opposed to knowledge of language), learned knowledge (as opposed to acquired knowledge), and Learned Linguistic Knowledge (as opposed to competence). It has also been associated with the notions of explicit knowledge and declarative knowledge, though considerable caution is required here. I will refer to it herein as “metalinguistic.”

1.2 Input

Many definitions have been offered for the term “input.” It is commonly understood in a traditional, intuitive way, partly reflecting the computer metaphor, and this makes a good starting point. But researchers have been aware for some time that considerable complexity lurks behind this neat metaphor. To understand input, we need to get beyond the surface, considering how it fits into the cognitive system as a whole.

1.2.1 Input: Basic Conceptions

Intuitively, the meaning of “input” seems clear. When we hear someone speak in the language that we are learning, what they say is input. When we read something in the language, what we read is input. Input is then “the material that is used for acquisition.” It is no surprise that the term evidence commonly appears in this context. Input is taken to be the evidence that learners use to determine the underlying nature of the language. The learner is then a kind of detective, or problem-solver, figuring out the principles of the language on the basis of available information – which is embodied in the input. In this conceptualization, input/evidence is naturally seen as instances of the language, providing information about its characteristics. The input-as-evidence idea can be seen in the term primary linguistic data commonly used in UG approaches, to be described in Section 2.

We normally think of input as what the learner gets from other people, but learners also hear (or read) the things that they themselves say (write), so input is sometimes taken to include their own production. This has been called virtual input (Reference Sharwood SmithSharwood Smith, 1981), auto-input (Reference Schmidt, Frota and DaySchmidt & Frota, 1986), and backdoor learning (Reference TerrellTerrell, 1991). We can imagine it playing a meaningful role in second language learning, and anecdotal evidence exists that it does play such a role, but to my knowledge the question has not been seriously investigated.

1.2.2 Complications in the Basic Conceptions

It is disturbingly easy to think of input as simply the language that learners are exposed to. But things are much more complex than such a surface view would suggest. First, we know that not everything learners hear actually contributes to their learning. For this reason, Reference CorderCorder (1967) introduced the notion of intake, to distinguish what is available for learning (input) from what actually gets used (intake). This distinction has become a standard part of thinking in the field, and it is the first step in developing a more sophisticated conception of input.

Reference KrashenKrashen (1981, Reference Krashen1982) emphasized that in order for input to be useful (to become intake, in Corder’s terms) the learner must be able to understand it, to derive its meaning. If I listen to a speech given in Swahili, I will not be acquiring Swahili. The practical point is that learners need materials that are not too difficult for them. The term comprehensible input has thus become a standard part of the vocabulary in the field. Reference Mason and KrashenMason and Krashen (2020a) characterized optimal input as that which is not only comprehensible but also abundant, rich in language, and “compelling” (see also Reference KrashenKrashen, 1982). Reference KrashenKrashen’s (1985) Input Hypothesis holds that comprehending input (optimal or not) is the essence of language acquisition.

It is important to recognize that the comprehension can come from a variety of sources, including the learner’s existing knowledge of the language but also such things as context, background knowledge, visual clues, translation, or direct explanation. This extra support can turn “too difficult” into “comprehensible,” allowing learners to take advantage of input that goes beyond their current knowledge of the language. Another kind of support is foreigner talk, the ways that native speakers of a language adjust their speech to make it more comprehensible to a non-proficient speaker. It commonly includes slowing down, speaking more loudly, simplifying, repeating, and pausing.

The concern with intake and comprehensibility brings out the importance of looking not just at what the learner is exposed to, but also at what happens to it as a result of the exposure. This point is reflected in Reference Sharwood SmithSharwood Smith’s (1993) definition of input as “potentially processible language data which are made available, by chance or by design, to the language learner” (p. 167, emphasis added). If a learner is not capable of doing anything (consciously or unconsciously) with an instance of the language, it is not input. An alternative would be to say that it is input of an irrelevant sort, what Corder would classify as input that will not become intake. The important point is that a study of input, however it is defined, must focus on language processing.

This insight has been expressed in a variety of ways. Reference GassGass (1997), for one, proposed that two stages precede the intake stage. Apperception connects the input to existing knowledge (or its absence) and can thereby identify an aspect of the input as significant, setting it up for further processing. This is followed by the stage of comprehended input, which then leads to the intake stage, at which the new information is incorporated in the grammar. Reference CarrollCarroll (1999) argued that a series of distinct stages of analysis lies between the immediate sensory experience and the language learning mechanisms, each step in the construction process producing the input for the following step. For Reference MacWhinney and RobinsonMacWhinney (2001), key to understanding acquisition is the way that learners use the various available cues in processing their input, cues such as word order, morphological markers, word meaning, and animacy.

Many researchers have stressed the importance of problems or limitations in learners’ processing of their input. Reference VanPatten, VanPatten, Keating and WulffVanPatten’s (2020) Input Processing is based on the observation that learners need to process their input correctly in order to benefit from it; training and practice in appropriate processing, focusing on places where things are likely to go wrong, thus becomes a worthy avenue of research. Pienemann’s (2020) Processability Theory holds that input is only useful if the current developmental state of the processor allows the learner to successfully process it. Reference O’GradyO’Grady (2015) and Reference Clahsen and FelserClahsen and Felser (2006) also stress, each in their own theory, the importance of difficulties and limitations L2 learners face in processing input. For N. Ellis (see Reference Ellis, Wulff, VanPatten, Keating and WulffN. Ellis & Wulff, 2020), the essential problem in L2 learning, distinguishing it from L1 learning, is that L1 processing experience has essentially set the system to ignore some aspects of the L2 (learned attention, blocking), so these aspects are in effect removed from the learners’ input.

The bottom line, again, is that we cannot understand input just as something out there. We also need to look at what goes on inside the learner’s head. What is out there retains an important role in any discussion of input, but also crucial are the learner’s ultimate interpretation of it and the process by which this interpretation is derived. It is perhaps best, then, to think of input not as a particular “thing” but rather as the name of a general topic: How what is out there comes to affect what is in the learner’s head.

1.3 Key Concepts Taken from Psychology

The importance of input for SLA lies in the contribution it makes to learning, and so learning can also be considered a key term in this area. Learning has always been a central concern of psychology, with ideas about it changing considerably over the years. A good contemporary account comes from Reference DehaeneDehaene (2020), who defines learning like this: “to learn is to form an internal model of the external world” (p. 5). He stresses that this model building is based on innate constraints – “Learning … always starts from a set of a priori hypotheses, which are projected onto the incoming data” (p. 26). Learning a language means forming a number of such models for the different components of language, based on innate constraints. The “incoming data” can be called input.

In SLA, the term “learning” is often used quite broadly, to mean simply positive changes in memory or ability. In this sense it is interchangeable with its companion term, acquisition, though a distinction is sometimes drawn between the two. Krashen in particular distinguished between a natural, unconscious process of acquisition and a more limited, conscious process of learning. When the process is viewed as natural and spontaneous development, the term growth is sometimes favored. The most neutral term is development.

L2 theory has conceptualized learning in a variety of ways. In UG approaches, for example, it means setting innate parameters, a process that is based on innate principles as well as existing settings (possibly the L1 settings) and of course input. Traditional skill-based approaches see learning as explicit study followed by proceduralization of knowledge and automatization of the resulting rules. In usage-based approaches, the heart of learning is statistical tallying of items in the input. Regardless of approach, a distinction is commonly drawn between implicit (unconscious) and explicit (conscious) learning. Increasingly important as well is the distinction between declarative and procedural learning, which is often seen now as a preferred alternative to dividing learning into implicit and explicit types (see Section 4).

The term incidental learning is sometimes associated with implicit learning but is probably better seen as the absence of an intention to learn (Reference SchmidtSchmidt, 1990). If a learner is only concerned with getting the meaning from input but in the process becomes aware of some aspect of form, learning that results from this encounter would be incidental but explicit, not implicit.

Memory can be thought of simply as what is learned, perhaps as the internal models of the world referred to in Dehaene’s definition of learning. And this simple view is often good enough for practical purposes. A serious interest in theory introduces a great many complications. Maybe for this reason, psychologists’ presentations of memory often do not include a general definition of the term, only of individual types of memory (e.g., Reference Baddeley, Eysenck and AndersonBaddeley, Eysenck, & Anderson, 2020). Alternatively, they offer lengthy discussion of complications inherent in the concept (e.g., Reference Tulving, Tulving and CraikTulving, 2000).

One important complication is that memory comes in a number of varieties. The most widely accepted categorization scheme starts by distinguishing long-term (LTM) from short-term memory (STM). Long-term consists of procedural memory, which is the knowledge underlying skills of all sorts, and declarative memory, which is then split into memories of events (episodic memory) and memory of facts (semantic memory). In SLA, the term knowledge typically covers the things that might otherwise be called long-term memory, as seen in the common terms implicit/explicit knowledge, procedural/declarative knowledge and, more generally, knowledge of language.

To these can be added working memory, a variant on the traditional idea of short-term memory emphasizing its active nature – we hold things in STM in order to use them. Increasingly important in SLA research is variation among learners in their working memory capacity, particularly how such variation correlates with success in various aspects of learning.

In current conceptions (see Reference Baddeley, Hitch, Allen, Logie, Camos and CowanBaddeley, Hitch, & Allen, 2021; Reference D’Esposito and PostleD’Esposito & Postle, 2015), working memory can almost be equated with attention – the things we are paying attention to are “in” working memory. The concept of attention has a long and very rich history in cognitive and neural research (see Reference CohenCohen, 2014; Reference Nobre, Mesulam, Kastner and NobreNobre & Mesulam, 2014), especially in the context of perception, and so, not surprisingly, has received extensive application in SLA. The logic of the application is straightforward: We are most likely to remember something, and to remember it most clearly and strongly, if we pay attention to it, so we might expect learners’ attention to input and to given aspects of it to be important for language learning. Attention has been closely associated with consciousness, in the cognitive literature and in SLA, though it would be a mistake to equate the two (Reference Koch and TsuchiyaKoch & Tsuchiya, 2012). Serious study of attention, like serious study of memory, takes us beyond the intuitive notion that we normally assume and introduces some complexities, to which I will return later.

Another important concept is consciousness (or awareness, often used as essentially synonymous). The term has been used in many different ways in different areas, but the meaning that is relevant here is the experiential one: We are conscious when we are in a normal waking state and unconscious when we are asleep or in a coma; we are conscious of something when that something is part of our immediate experience. The role of consciousness, in this sense, has always been a key issue in second language learning, if often implicitly. To what extent is learning a conscious process? Differing answers have inspired (or perhaps justified) differing approaches to teaching.

A number of common terms are related to consciousness. Reference KrashenKrashen’s (1981, Reference Krashen1982) conscious learning and unconscious acquisition are foundational concepts in the field, though the use of the terms has faded. The preferred terms now are explicit (conscious) and implicit (unconscious), reflecting prominent work in cognitive psychology (see Reference Reber and AllenReber & Allen, 2022). The terms distinguish both two types of learning and two types of knowledge. Especially important in the context of input are Reference SchmidtSchmidt’s (1990) notions of noticing and noticing the gap (Reference Schmidt, Frota and DaySchmidt & Frota, 1986). Noticing, for Schmidt, referred to a conscious registration of something present in the input, without regard to whether the learner knows what that something is or what it means. The term is commonly used with a much broader, ordinary language meaning, though. Noticing the gap is awareness that something in the input is not consistent with the current state of the interlanguage, though again the term is often used loosely. Prominent in the literature is Reference SchmidtSchmidt’s (1990) Noticing Hypothesis, which states that awareness of features of the input – “noticing” – is necessary for their acquisition.

Perception, the way that information from the senses is processed and interpreted, has not received a great deal of explicit attention in SLA. But input processing is itself a form of perception and so the concept deserves recognition here. I will consider it in some detail in Section 4 (for introductions to perception, see Reference MatherMather, 2011; Reference Wolfe, Kluender and LeviWolfe et al., 2018).

Other significant concepts in the area of input involve its emotional, or affective, aspect. It is generally agreed that language learning and language use are influenced by emotions such as anxiety, pride, and embarrassment, as is expected given the nature of perception, learning, and memory in general. Reference KrashenKrashen (1981, Reference Krashen1982; Reference Dulay, Burt and KrashenDulay, Burt, & Krashen, 1982) captured the relation in his affective filter, the idea being that negative emotion prevents input from reaching its destination, that is from being used in acquisition. Reference Sharwood SmithSharwood Smith (1996) briefly considered a possible positive role of affect, suggesting that in order to be useful for learning, input requires an affective “validation.” In the Modular Cognition Framework (Reference Truscott and Sharwood SmithTruscott & Sharwood Smith, 2019) this led to the notion of value assigned to instances of input and therefore to the target language and aspects of it (see Section 4). Dulay, Burt, and Reference KrashenKrashen’s (1982) speaker models and Reference Beebe, Gass and MaddenBeebe’s (1985) notion of learner preferences also address the relation between affect and input. The idea, in each case, is that learners attend specifically to the speech of people that they choose as their models and not to that of others, in effect selecting the input that they want to take in.

1.4 Key Concepts Associated with Instruction

A number of relevant terms are associated primarily with language instruction. One group involves the increasingly popular approach of using the target language, wholly or in part, to teach content. Such instruction is not intended specifically to provide extensive input, but this feature tends to dominate, if only because the classroom setting is more conducive to listening experience than to speaking experience. This type of instruction includes immersion, content and language integrated learning, bilingual education, content-based instruction, content-based language teaching, dual language education, and English medium instruction. The ideas and practices overlap greatly, a single type is commonly divided into several sub-types, and the terms themselves can have different meanings to different people (see, for example, Cenon, Genesee, & Gorter, 2014). The details of this confusing picture are peripheral to a discussion of input and so I will not pursue them here.

Instruction often includes efforts to provide learners with as much input as possible, spawning a number of common terms. Extensive reading is what its name suggests. Variant terms, sometimes involving limited adjustments, include free voluntary reading, sustained silent reading, guided self-selected reading, and pleasure reading, the latter term bringing out the emphasis commonly placed by proponents on the importance of learners’ enjoyment. Narrow reading focuses on works dealing with a particular topic or by a particular author. Paralleling extensive and narrow reading are extensive listening and narrow listening. To these can be added extensive viewing, which takes advantage of the visual clues provided by videos, for example. Its natural companion term is narrow viewing.

Reference LongLong (1983) argued that input is most effective when it occurs in the context of interaction. On this idea, instruction should emphasize two-way communication, in which negotiation between the participants results in modification of “the interactional structure of conversation.” Intimately associated with interaction is focus on form, introduced by Reference Long, de Bot, Ginsberg and KramschLong (1991). He defined it in part by contrast with focus on forms. The latter is essentially traditional grammar instruction, especially that following a grammatical syllabus. In focus on form, in contrast, activities are meaning-focused but with aspects of form explicitly addressed in the context of those activities. This can be seen especially now in task-based instruction. Input is a natural part of such instruction and the interventions are likely to be focused on aspects of the input, but it is only one part of the instruction.

Discussion of this topic requires some caution because “focus on form” has not always been used with the meaning that Long gave it. After Long’s proposal, the term became very popular, to the extent that it was sometimes applied to instruction and research that looked more like focus on forms. That said, the idea has generated a tremendous amount of research and will no doubt continue to do so. The looser term form focus is also in common use.

Intimately associated with interaction, as well as focus on form, is corrective feedback. It is a prominent research topic in both written and oral contexts. Particularly noteworthy in this context are recasts, which might well be considered a form of input.

Student: I yesterday went to the library.

Teacher: You went to the library yesterday.

Finally, ideas about output have acquired a prominent place in SLA, notably in Reference Swain, Gass and MaddenSwain’s (1985, Reference Swain and Hinkel2005) Output Hypothesis, which holds that comprehensible input must be supplemented by output practice.

Reference Sharwood SmithSharwood Smith (1981) introduced the idea of consciousness raising, in which learners discover features of the language guided by the teacher in different ways and to different degrees. To avoid the implication that changes in the learner’s state of mind (consciousness) are an essential feature of the process, he later offered input enhancement as an alternative term (Reference Sharwood SmithSharwood Smith, 1993), highlighting the fact that it is an external adjustment, which might or might not be reflected in the learner’s mind. This term has since become an institution in the field. As it is usually understood, input enhancement is about making selected aspects of input more salient in the hope that this will facilitate acquisition of those aspects (see Reference Sharwood SmithSharwood Smith, 1991, Reference Sharwood Smith1993).Footnote 2 A teacher or textbook writer might place past tense endings in bold, for example, to draw learners’ attention to those forms. The oral equivalent would be to stress the forms.

An alternative to making a feature especially salient in a given instance is to provide input that contains many instances of that feature. A text might be written to include repeated use of passive forms, for example. This idea of an input flood (Reference Trahey and WhiteTrahey & White, 1993) was included in early notions of consciousness raising (Reference Rutherford and Sharwood SmithRutherford & Sharwood Smith, 1985), though it was only noted briefly and without the name. It might be considered a form of input enhancement, and is sometimes used in combination with more prototypical varieties.

The notion of salience is crucial here, and also has more general significance for SLA. Learners’ success in acquiring a linguistic element might be affected by whether that element is especially salient or especially nonsalient in the input. The term has most often been used in an intuitive sense, making serious study difficult, but efforts have been made to deal with it in a more solid and scientific manner (see Reference Gass, Spinner and BehneyGass, Spinner, & Behney, 2018).

2 What Are the Main Branches of Research?

Because input is tied up in one way or another with almost everything in SLA, identifying branches of research on input is challenging, and decisions are to some extent arbitrary, especially because extensive overlap exists among various branches, as they deal with intertwined issues, though often in different terms. I will focus on research that is most clearly, explicitly about input but will sometimes wander away a bit as needed.

2.1 Maximizing General Exposure to (Comprehensible) Input

If input, and comprehension of input, is the heart of learning, then a natural goal for instruction is to maximize the learners’ exposure to the language, in ways that facilitate comprehension. Some approaches to teaching adopt this as their primary goal (Reference AsherAsher, 2012; Reference Krashen and TerrellKrashen & Terrell, 1988; Reference Mason and KrashenMason & Krashen, 2020b; Reference WinitzWinitz, 1981, Reference Winitz2020). Not surprisingly, a significant amount of relevant research exists.

2.1.1 Extensive Reading and Its Variants

Extensive reading has been extensively researched. A noteworthy example is the book flood approach of Reference ElleyElley (1991, Reference Elley2000). Elementary school learners were presented with a large number of books, selected to be of interest to them. Class activities included reading aloud by the teacher, discussion, and sometimes writing, so this was not “pure” extensive reading. The goal was, however, to provide learners with extensive exposure to the target language with a focus on meaning rather than form. The approach was used in a number of countries, focusing on the South Pacific but extending beyond this region. In each case Elley reported strongly positive results, using a variety of tests.

A number of reviews and meta-analyses of extensive reading research are available (Reference Day, Bassett and BowlerDay et al., 2016; Reference Jeon and DayJeon & Day, 2016; Reference NakanishiNakanishi, 2014, Reference Nakanishi2015; Reference Ng, Renandya and ChongNg, Renandya, & Chong, 2019). The research has addressed a variety of possible benefits, including vocabulary learning, reading comprehension, reading speed, writing, and grammar – with generally positive findings. Thus, the case for extensive reading is quite strong, though most would see it as one important part of an overall program rather than a method in itself (see for example the interview with Paul Nation – Reference Iswandari and ParaditaIswanda & Paradita, 2019).

An interesting variant of extensive reading, again, is narrow reading (Reference KrashenKrashen, 2004), focusing on works on a particular topic or by a particular author. This approach serves the basic goals of improving comprehensibility and enhancing pleasure (assuming learners are allowed to choose their topics), as well as recycling vocabulary to make it more easily remembered. Research is limited but offers some reason to think that it is beneficial for vocabulary learning (Reference ChangChang, 2019; Reference Cho, Ahn and KrashenCho, Ahn, & Krashen, 2005; Reference KangKang, 2015).

Extensive reading might or might not be supplemented in various ways. Additions are typically used to assist or check comprehension, as in the use of glosses and comprehension questions, though a variety of exercises can and have been used as well. When grammar is the focus of the activities, we are leaving the realm of “maximizing general exposure” and moving into focus on form (see discussion). The boundary between the two is, however, somewhat fuzzy, because grammar and meaning are of course intertwined with one another. When a teacher points to the word women to clarify that more than one woman is involved or to was to tell learners that a passage is about something that was true in the past, this does not mean abandoning a meaning-focused approach. But it is, in a limited way, bringing in a form focus, drawing learners’ attention to form. It thus belongs to an inevitable gray area between simple meaning-oriented exposure and form focus.

2.1.2 Extensive Listening and Viewing

The logic of extensive reading is naturally applied to extensive listening (see Reference Ivone and RenandyaIvone & Renandya, 2019), and the two are sometimes combined. Research is much more limited than that on extensive reading, and there does not seem to be any systematic effort to empirically evaluate its effectiveness, particularly in relation to the much more established practice of intensive listening. The limited research focuses instead on issues of how it should be carried out (see Reference MasraiMasrai, 2019; Reference MatsuoMatsuo, 2015; Reference RodgersRodgers, 2016; and sources cited by them). The effectiveness of the Story-Listening approach has been examined in several studies, with favorable results reported (Reference Mason and KrashenMason & Krashen, 2020b; Reference Mason, Smith and KrashenMason, Smith, & Krashen, 2020). Narrow listening (Reference KrashenKrashen, 1996), paralleling narrow reading, has also received some limited investigation. Reference TsangTsang (2022) and Reference ChangChang (2019) found it beneficial for spoken proficiency and vocabulary learning, respectively.

TV, movies, videos, and lectures are a natural source of aural input, contributing visual information that can assist comprehension, so extensive viewing is an additional, and possibly improved, form of extensive listening (see Reference Webb, Nunan and RichardsWebb, 2015), along with its natural companion, narrow viewing (Reference Rodgers and WebbRodgers & Webb, 2011). The line between extensive and non-extensive is far from clear, and so discussion of the former can readily lead into a vast literature on incidental learning, especially vocabulary learning, through various media, often supported by a variety of aids for comprehension and/or explicit learning, again leading into the realm of form focus. I will not try to deal with this literature here.

2.2 Input Enhancement and Input Flood

Input enhancement, again, is about making selected aspects of input more salient in the hope that this will facilitate acquisition of those aspects. The idea of enhancing input has generated a considerable amount of research (for review, see Reference BenatiBenati, 2016; Reference GascoigneGascoigne, 2006; Reference Han, Park and CombsHan, Park, & Combs, 2008; Reference Lee and HuangLee & Huang, 2008; Reference Nassaji, Loewen and SatoNassaji, 2017; Reference Pellicer-Sánchez, Boers, Siyanova-Chanturia and Pellicer-SánchezPellicer-Sánchez & Boers, 2019). Results have been inconsistent and not particularly impressive overall. Inconsistent results are commonly attributed, at least to a large extent, to differing methodologies, with unclear implications. Making sense of the findings probably also requires us to place them within a broader understanding of the mind, which is to say within a general theoretical framework (Reference Sharwood Smith and TruscottSharwood Smith & Truscott, 2014a). If we want to understand how adjustments in learners’ input impact their learning, we first need a clearer idea of how input is processed. Another limitation of the research is that the focus is almost always on the strictly linguistic aspects of the input. The focus could be expanded to include enhancement of other aspects, such as affect and context.

The alternative to standard input enhancement is to provide input that contains many instances of a selected feature, like simple past tense forms – an input flood. This approach has received much less attention in the research, but a number of studies have been done, a typical conclusion being that the flood can, inconsistently, help learners produce correct instances of the language but does not help them avoid incorrect instances (for review of the research, see Reference BenatiBenati, 2016; Reference Nassaji, Loewen and SatoNassaji, 2017; Reference Pellicer-Sánchez, Boers, Siyanova-Chanturia and Pellicer-SánchezPellicer-Sánchez & Boers, 2019).

2.3 Noticing and Noticing the Gap

The terms “noticing” and “noticing the gap,” ubiquitous in the literature, embody the idea that consciousness has a central role in second language learning. Paradoxically, their origin lies in Reference Krashen, Gass and SelinkerKrashen’s (1983) discussion of the way that input is used, unconsciously, in acquisition. He suggested that learners “notice (at a subconscious level)” both elements of the input and any “gap” that exists between those elements and the current state of their knowledge. This comparison process leads to acquisition. To this picture Reference Schmidt, Frota and DaySchmidt and Frota (1986) added, contrary to Krashen’s thinking, the hypothesis that the noticing is necessarily conscious – learners have to be aware of both the linguistic elements and the contrasts in order to benefit from their presence. Reference SchmidtSchmidt (1990) took the idea further, developing a more technical notion of noticing, which served as the basis for his Noticing Hypothesis – in order to benefit from input, learners must be aware of the relevant aspects of form in the input.

Noticing and the noticing hypothesis are referred to in a great deal of research on language instruction. Most of the work does not study them as such, though; the authors present them as background for the study or appeal to them as possible ways to understand the findings. A frequent but typically unrecognized problem in these references is that the meaning assigned to the word “noticing” shifts (see Reference Truscott and Sharwood SmithTruscott & Sharwood Smith, 2011). Reference SchmidtSchmidt (1990) was proposing a technical notion, with a relatively narrow meaning that excluded much, and probably most, of the things that researchers are interested in. Not surprisingly, then, there is a strong tendency in the literature to fall back on the ordinary language meaning of the word – awareness of something (anything). This research generally falls in the category of form focus, which I will briefly describe herein and then return to in Section 5.

A number of studies have specifically targeted the noticing hypothesis, usually with a recognition of the relatively narrow scope of “noticing.” This means bringing in the accompanying notion of “awareness at the level of understanding” (see especially Schmidt, 1995), a type of awareness that was excluded from the hypothesis but is important in the context of second language instruction. An important addition to this research area is the application of eye-tracking methodology to determine what is or is not noticed (see Reference GodfroidGodfroid, 2020). Several reviews of noticing research are available (Reference Gass, Behney and PlonskyGass, Behney, & Plonsky, 2020; Reference LeowLeow, 2015; Reference LoewenLoewen, 2020; Reference Loewen and SatoLoewen & Sato, 2017), reporting mixed findings. The issues involved in noticing and the research exploring it are large and complex, and I will not go into them here (for critical reviews, see Reference ParadisParadis, 2004, Reference Paradis2009; Reference TruscottTruscott, 1998; Reference Truscott and Sharwood SmithTruscott & Sharwood Smith, 2011; Reference VanPattenVanPatten, 1994, Reference VanPatten2015).

2.4 Implicit Knowledge and Implicit Learning

The notion of implicit (unconscious) knowledge/learning comes from cognitive psychology (e.g., Reference ReberReber, 1993), particularly from experiments designed to test the possibility that people can learn things without being aware of what they learned or of the fact that they learned it – in other words, the possibility of implicit knowledge and implicit learning. In one design, participants see a row of lights in front of them flashing on and off in patterns that appear random but actually follow a pattern, of which they were not told. Their task is to respond to a given light going on by pressing the button corresponding to that light as quickly as possible. It was found that their reaction times gradually decreased, as if they were correctly anticipating the lights, but no conscious knowledge of the underlying pattern could be found by the experimenters, apparently indicating that they had acquired implicit knowledge, through implicit learning.

The other standard paradigm for implicit learning research, which is perhaps more relevant here, uses small artificial grammars, mimicking natural language grammar. Learners are presented with large numbers of “sentences” that can be produced by the grammar and then tested on how well they can judge if other instances, not previously shown to them, can or cannot be produced by that grammar. If they show some ability to do so, as they often do, and do not show any signs of conscious knowledge of how they are doing it, we have evidence of implicit learning and implicit knowledge.

The implicit learning literature is enormous (see especially Reference Reber and AllenReber & Allen, 2022), and it has established beyond any reasonable doubt that implicit knowledge and learning are real and important. It is commonly conceptualized in terms of statistical learning, involving the frequencies of individual items and of the associations between them (see Reference Rebuschat, Reber and AllenRebuschat, 2022, for relevant discussion). This conception is developed especially in usage-based approaches (e.g., Reference Ellis, Wulff, VanPatten, Keating and WulffN. Ellis & Wulff, 2020). Unconscious knowledge and learning need not be seen in these terms, though. Universal grammar theorists, for example, typically take a very different view of unconscious knowledge and learning (see discussion).

The importance of implicit knowledge and learning for SLA has come to be widely recognized (see Reference Lichtman and VanPattenLichtman & VanPatten, 2021; also the various papers in Reference EllisN. Ellis, 1994; Reference RebuschatRebuschat, 2015; Reference Sanz and LeowSanz & Leow, 2011; Reference VanPatten, Keating and WulffVanPatten, Keating, & Wulff, 2020). The terms “implicit” and “explicit” now appear very widely in the research, notably in work on the effects of formal instruction. Researchers are interested in the effects of pedagogical interventions on the development of each type of knowledge and in the possible interactions of the two. For this purpose there is a need for means of distinguishing them in practice, a challenge that was taken up by Reference EllisR. Ellis (2005; see also Reference Ellis, Loewen and ElderR. Ellis et al., 2009). The criteria he offered are widely applied in research. But in this work, the role of input is at best a peripheral concern; its effects are tangled up with the effects of explicit instruction and other factors.Footnote 3 Another limitation of this work is that when implicit knowledge is acquired we do not know how it was acquired – implicitly or explicitly or through some combination of the two.

A substantial body of SLA research more directly addresses implicit learning and implicit knowledge, by studying them in controlled conditions (e.g., Reference Brooks and KempeBrooks & Kempe, 2013; Reference DeKeyserDeKeyser, 1995; Reference Hama and LeowHama & Leow, 2010; Reference Leung and WilliamsLeung & Williams, 2011; Reference Rogers, Révész and RebuschatRogers, Révész, & Rebuschat, 2016; Reference WilliamsWilliams, 2005). This work has made it reasonably clear that implicit learning does occur at least sometimes, though results are inconsistent. Perhaps more importantly, research of this type encounters serious issues of ecological validity, as it is difficult to pursue the questions in realistic contexts with realistic input and realistic measures of learning. We know that language-related knowledge can be implicitly acquired in laboratory settings, but what this tells us about actual language learning is open to dispute.

A significant issue for the study of implicit learning is whether it is influenced by explicit knowledge. We should expect there to be at least some influence of this sort, because of the potential of explicit knowledge for making input more comprehensible and its possible use by a learner to create virtual input (see Section 1). But the broader question is difficult to directly study. The problem of distinguishing implicit from explicit knowledge becomes severe when the latter has been automatized through extensive use and so is now used quickly and effortlessly and with little awareness. Reference DeKeyser, Loewen and SatoDeKeyser (2017; Reference Suzuki and DeKeyserSuzuki & DeKeyser, 2017) has been especially concerned with this problem, as automatized explicit knowledge has a central place in his theory.

Reference Suzuki and DeKeyserSuzuki and DeKeyser (2017) sought to empirically test the possibility that automatized explicit knowledge contributes to implicit knowledge. The measures that were used for automatized explicit knowledge are a possible issue in this study. The tests were timed grammaticality judgments, both written and aural, and a timed fill-in-the-blank task. The problem is that these tasks readily lend themselves to the use of implicit knowledge – people can easily perform them in their native language, for example, whether or not they have explicitly studied grammar. While the authors may be right that the tasks encouraged learners to focus on form and so encouraged the use of automatized explicit knowledge, a claim that implicit knowledge played no role in them, or that it had only a negligible role, seems doubtful. If the “explicit” tasks allowed even a fairly small role for implicit knowledge, then the weak relation that was found can be readily interpreted as a relation not between implicit knowledge and automatized explicit knowledge but rather between implicit knowledge and implicit knowledge. This is not, however, reason to close the book on research of this sort – challenges can be overcome.

2.5 Attention

Attention is an important topic in SLA, and the term appears throughout the literature. It is usually not treated as a distinct branch of its own, though, as most research on attention in SLA can also be classified as work on consciousness, noticing, implicit learning, input enhancement, focus on form, and possibly other topics as well.

Attention has been the focus of some theoretical work in the field. Reference GassGass’ (1988) integrated model of SLA (see also Reference Gass, Behney and PlonskyGass, Behney, & Plonsky, 2020, Ch. 17) gives attention a central place. Thinking on attention in SLA has been strongly influenced by Posner’s theory (see Reference PosnerPosner, 2012; Reference Posner and PetersenPosner & Petersen, 1990; Reference Posner, Rothbart, Milner and RuggPosner & Rothbart, 1992), in which attention is split into three parts: alertness (or vigilance), orientation toward the stimulus, and detection of the target. Reference Tomlin and VillaTomlin and Villa (1994) was essentially an application of the theory to SLA. Posner’s work was also used by Reference RobinsonRobinson (1995), who interpreted noticing as detection (of a formal feature in the input) accompanied by rehearsal of that feature in working memory.

Much of Schmidt’s writing on noticing (see especially Reference Schmidt and RobinsonSchmidt, 2001) focused on attention rather than consciousness, treating the two as essentially equivalent for his purposes. He argued that attention is necessary for all aspects of second language learning. While the claim has appeal, there is a problem, for this and other applications of attention to SLA. As Schmidt noted, the word “attention” has a variety of meanings in psychology. A consensus appears to exist in cognitive theory that there is in fact no single thing to which the term applies. It is a blanket term covering many different processes (e.g., Reference Allport, Meyer and KornblumAllport, 1993; Reference CohenCohen, 2014; Reference Nobre, Mesulam, Kastner and NobreNobre & Mesulam, 2014). For Nobre and Mesulam, the treatment of attention as a domain in itself has probably been a mistake; the features associated with “attention” should instead be studied as inherent parts of a wide variety of processes. There is also a danger of “attention,” like “noticing” being used in a loose, ordinary-language sense and thereby losing what scientific foundation it has. These are general issues for work that invokes attention.

2.6 UG-based Research

Universal grammar (UG) is the innate knowledge of language hypothesized to underlie first language acquisition. The extension to second language acquisition constitutes a rich area of research (see Reference HawkinsHawkins, 2019; Reference Mitchell, Myles and MarsdenMitchell, Myles, & Marsden, 2019; Reference Slabakova, Leal, Dudley and StackSlabakova, Leal, Dudley, & Stack, 2020; Reference White, VanPatten, Keating and WulffWhite, 2020), but input in itself has not been a major concern in this research, a point brought out by Reference Rankin and UnsworthRankin and Unsworth (2016). From a UG perspective, the core of acquisition is establishing the values of various innately given parameters, determining word order for example. This is done through input, of course, but UG researchers have generally been more interested in showing the insufficiency of input for learning.

The acquisition process involves learners analyzing their input, on the basis of the innate principles and the L1, and making deductions from it about the nature of the target language. This is an “input as evidence” conception, the learner seen as a detective using evidence to solve a problem. So the way that input is analyzed or misanalyzed by learners, often reflecting L1 influence, is an important concern. Within this deductive approach, there is now a general recognition that frequency is important.

The bulk of the research that has been done within the UG perspective has assumed Chomskyan linguistic theory, in one form or another. But there is substantial variety among theories. Reference JackendoffJackendoff’s (1997, Reference Jackendoff2002) linguistic theory deviates considerably from Chomsky’s thinking but remains very much within the UG camp. In SLA, the Modular Cognition Framework (e.g., Reference Sharwood Smith and TruscottSharwood Smith & Truscott, 2014b; Reference Truscott and Sharwood SmithTruscott & Sharwood Smith, 2019), along with Reference CarrollCarroll’s (2001) Autonomous Induction Theory, assumes UG but is not committed to any particular linguistic theory. Reference VanPatten, VanPatten, Keating and WulffVanPatten’s (2020) work similarly takes UG as a background assumption but focuses on the processing that produces the input to innate learning processes, leaving the nature of these processes as an open question.

2.7 Input Processing and Processing Instruction

Reference VanPatten, Piske and Young-ScholtenVanPatten’s (2009, Reference VanPatten, Loewen and Sato2017, Reference VanPatten, VanPatten, Keating and Wulff2020) Input Processing and Processing Instruction have spurred a considerable amount of research and are likely to continue to do so. VanPatten’s work combines serious theoretical development, empirical research, and pedagogical application, all focused on input as the key to learning. The work is based on the fundamental point that learning depends on the way that learners process input.

The first issue then is how the processing occurs, and this is the domain of Input Processing (IP). VanPatten accepts the existence of universal grammar as a crucial part of acquisition, but does not give it a direct role in processing. Instead, separate processing mechanisms prepare the input for use by learning mechanisms, including UG. IP is about the processing mechanisms, for which a number of general principles are hypothesized. This understanding of input processing points to possibilities for pedagogical intervention (Processing Instruction, or PI). If the processing principles being used by learners are inappropriate for the language they are acquiring, the learning mechanisms will receive bad input, and learning will suffer as a result. If the processing procedures can be altered to a more appropriate form, learning will benefit. VanPatten stresses that this is not a method or an approach but rather a particular sort of intervention that can be used in a wide assortment of methods.

IP and PI have, again, stimulated a large body of experimental research (see Reference VanPatten, Piske and Young-ScholtenVanPatten, 2009, Reference VanPatten, Loewen and Sato2017, for lengthy lists of references). As the goal of PI is to alter processing strategies, this is the focus of the research, and the main conclusions are that it is successful in this respect, both in absolute terms and relative to other types of intervention. Importantly, it is not claimed to improve learners’ communicative ability.

2.8 Use of the Target Language to Teach Content

Use of the target language to teach content is an increasingly popular approach, appearing in a variety of forms. Considerable research has been carried out in classes of these types (e.g., Reference Collier and ThomasCollier & Thomas, 2017; Reference Feddermann, Möller and BaumertFeddermann, Möller, & Baumert, 2021; Reference Graham, Choi, Davoodi, Razmeh and DixonGraham, Choi, Davoodi, Razmeh, & Dixon, 2018; Reference Martínez AgudoMartínez Agudo, 2020; Reference Watzinger-Tharp, Rubio and TharpWatzinger-Tharp, Rubio, & Tharp, 2018). In the SLA literature, the immersion research in Canada has played an especially important role (e.g., Reference CollierCollier, 1992; Reference Swain and FreedSwain, 1991). The approach tends to do well, though results are variable and it is difficult to draw general conclusions given the variety of pedagogical approaches that fall under this general heading. A common finding is that learners tend to do especially well in comprehension, often attaining native-like ability, but are somewhat less successful with productive skills. Proposed explanations for this limitation have included limited opportunities for production, narrow or impoverished input, and insufficient formal language instruction or insufficient integration of such instruction with content-based teaching (e.g., Reference Snow, Met and GeneseeSnow, Met, & Genesee, 1989; Reference Swain, Gass and MaddenSwain, 1985).

2.9 Interaction, Focus on Form, Output, and Corrective Feedback

The topics of this section are all major research areas in SLA and are intertwined with one another in theory, research, and pedagogy. They are also intertwined with input and so are relevant here, but input is not a central theme and the research does not seek to isolate or focus on input as such and so inferences about its nature or role are not straightforward.

The role of interaction in second language learning constitutes a particularly rich research area, or perhaps a cluster of rich research areas. The target of this work, interaction, is a coherent package of input, output, and feedback, within a communicative context in which meaning is negotiated between the participants. While the role of input is not isolated, most will agree that it is central. The primary motivation for Long’s early, influential proposals was in fact the idea that interaction should contribute greatly to the goal of providing comprehensible input (see Reference LongLong, 1983, Reference Long, Ritchie and Bhatia1996).

There does not seem to be any dispute regarding the value of the overall package for acquisition. This value can probably be accommodated in all major theories, and interaction research can potentially contribute to the development of SLA theory quite broadly. Probably the bulk of the research falls under the heading of focus on form, or more loosely form focus. It should be stressed that, despite the name, form focus as it is commonly recommended now treats meaning as primary, placing the form focus in the context of meaningful activities.

All the topics considered in this section are closely associated with work on consciousness and attention, described earlier, notably work on noticing and the implicit-explicit distinction. The sources cited there are also relevant here. Extensive review and discussion of research in this group of interrelated topics can be found in Reference Gass, Behney and PlonskyGass, Behney, and Plonsky (2020), Reference Gass, Mackey, VanPatten, Keating and WulffGass and Mackey (2020), and Reference Loewen and SatoLoewen and Sato (2017).

2.10 Input and the Development of Phonology

In much SLA work, including work on input, phonology tends to be taken for granted. But phonological processing and learning is in a sense the most fundamental issue, as all spoken input – and any resulting acquisition – begins with perception of the sounds. A substantial body of research exists on the development of second language phonology, and much of it involves input (e.g., Reference Bohn and MunroBohn & Munro, 2007; Reference Flege, Piske and Young-ScholtenFlege, 2009; Reference Kennedy, Trofimovich, Loewen and SatoKennedy & Trofimovich, 2017; Reference Piske and Young-ScholtenPiske & Young-Scholten, 2009; Reference White, Titone, Genesee and SteinhauerWhite, Titone, Genesee, & Steinhauer, 2017; Young-Scholten, 1996).

Largely the same issues arise here as in other areas of input research. First, the importance of input for development is acknowledged, while research is directed to the question of how important it is relative to the other factors, such as the L1 and the age of the learner. The role of consciousness and attention is a common theme in the research, frequently cast in terms of noticing. This concern is naturally accompanied by applications to pedagogy, including issues of output practice, explicit instruction, interaction, and input enhancement. The question of innateness is also pursued – the possible innateness of principles involving hierarchies and markedness as well as stages of development possibly arising from innate constraints (Universal Phonology).

2.11 Conclusion

Identifying distinct branches of research on input is, again, difficult and somewhat arbitrary. We might add research done within given SLA theories, like Reference O’GradyO’Grady’s (2005, Reference O’Grady2015) emergentist model, MacWhinney’s (Unified) Competition Model (e.g., Reference MacWhinney, Gass and MackeyMacWhinney, 2012), and Pienemann’s Processability Theory (see Reference Pienemann, Lenzing, VanPatten, Keating and WulffPienemann & Lenzing, 2020). I have left out these and other theories because, while their treatment of input is important, the research done within them is rarely focused on it. I have also left out most research done within socially or culturally oriented theories because “input,” as a cognitive, information-processing concept, is not widely accepted in these areas and does not play a major role in the research. Likewise for the Complex Dynamic Systems Theory developed for SLA by Reference Larsen-Freeman, VanPatten, Keating and WulffLarsen-Freeman (2020), who rejects the term “input” as dehumanizing (among other objections).

3 What Are the Implications for SLA?

The term “SLA” can be understood in a broad sense to include all work related to the acquisition of languages beyond the first. But here it will be used in the narrower sense of theory and research attempting to establish a scientific understanding of the subject, as distinct from efforts to establish useful guidelines for instruction. The latter will be considered in Section 5. The question at this point is what lessons might be drawn from existing research for the development of a scientific understanding of SLA. The discussion will be relatively brief, its purpose being to offer a perspective on previous sections and an introduction to Sections 4 and 5, where most of the topics will be explored in more depth.

The first lesson I would draw is that caution is required. While much has been learned, it would be bold to claim that we have achieved a general understanding or that commonly accepted ideas are now on solid ground. At this point, lack of consensus is not a problem; it is an honest recognition that while we may be on the road to real understanding, the destination is not yet in sight. That said, a number of significant points can be drawn from the research.

First, input is not just something out there. To understand the subject, we have to recognize that what is out there goes through an elaborate construction process on its way to influencing language learning. Input is best seen as the name for this process, or as the general topic of how what is out there affects what is in the learner’s head. This topic might well be characterized simply as perception – the study of how perception works in the case of second language learning.

Perhaps the most prominent theme in current research is the importance of implicit knowledge acquired in implicit learning, through input processing. There does not seem to be any serious dispute any longer regarding the existence of two distinct types of knowledge/learning, or the primacy of the type that is commonly characterized as implicit. The explicit variety of knowledge, obtained through other means, has value for learning and for use but is very much secondary – the extent of its value is a significant topic for continuing research.

Given the prominent role of implicit knowledge and learning and their contrast with explicit knowledge and learning, a crucial question is whether this is in fact the right way to draw the distinctions. Should theory and research findings be recast in terms of the procedural-declarative distinction? This would mean drawing the lines without reference to consciousness and then asking to what extent and in what ways consciousness is associated with the actual systems. I will consider this and related theoretical issues in Section 4.

There has been extensive work on the effects of instruction on implicit and explicit knowledge, including efforts to separate them using different types of tests. While claims are made about benefits for implicit knowledge, it is not easy to see how benefits from relatively brief, explicit treatments can be explained in terms of the gradual statistical tallying that is commonly taken to underlie the development of implicit knowledge. This suggests either that it is not implicit knowledge that is being acquired or that different conceptions of implicit knowledge and/or learning are needed.

Efforts to influence (implicit) learning by directing learners’ attention to features of their input have not fared particularly well in the research, a point that is far from conclusive but should raise some doubts about the value of attention to form and awareness of form. There is good reason to think that VanPatten’s processing instruction helps learners deal with problematic input, but the effects on language acquisition itself remain uncertain.

Continuing development and testing of theoretical approaches is necessary. Linguistic theory plays a crucial role – we cannot understand how knowledge is acquired without understanding what that knowledge looks like. It should not be forgotten, though, that there is not, as of yet, any definitive answer to the question of what language really looks like. The view of language on which a given approach rests is always open to challenge. Research and theory in psychology are also of great value and should continue to play an important role, though their application is by no means straightforward, nor are particular applications uncontroversial. The contrast between technical meanings of terms and their intuitive, ordinary-language meanings must be recognized.

One fundamental issue is not receiving anything like the attention it deserves. This is the foundational issue for a theory of learning: How do the proposed learning mechanisms know what to look for in their input? Our remarkable ability to make sense of what we encounter requires an account of how these mechanisms manage to focus in on the things they need without getting lost in the vast complexity of the world in which those things are embedded. This issue brings out the need for a stronger theoretical grounding.

An increased concern with theory means seriously pursuing questions that are fundamental for an understanding of input but are rarely if ever addressed, or even recognized as questions. Consciousness of input and attention to input are central issues in SLA. But input is a multi-stage construction process rather than a thing in itself. So what exactly does it mean to be conscious of input, or to attend to it? To pursue the question, we need both a more refined concept of input and clear ideas of how consciousness and attention fit into the perceptual process that is input. In their absence, “conscious of input” is vague or ambiguous; for serious study of input, this is not good enough.

4 An Integrated View of Input in Second Language Learning

It is time to put things together into what will hopefully be a coherent picture of input and its place in second language learning, one that will, among other things, address the fundamental questions just raised. The picture will be a cognitive one, placing the topics in the context of cognitive research and theory. More specifically, it will be my own picture, based on the Modular Cognition Framework (MCF; e.g., Reference Sharwood Smith and TruscottSharwood Smith & Truscott, 2014b; Reference TruscottTruscott, 2022b; Reference Truscott and Sharwood SmithTruscott & Sharwood Smith, 2019).

4.1 Input, Perception, and Bird Calls

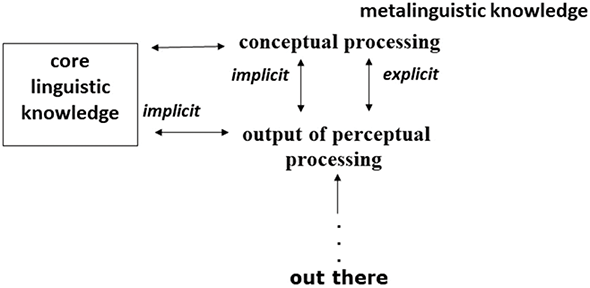

The first and most important topic is perception. And the first and most important thing to understand about perception, as noted in Section 1, is that it is not a process of taking what is outside and bringing it inside. It is about constructing internal representations of experiences. The representation constructed in this way is connected to already stored objects, and associated with related knowledge and with emotion. The end result of the process is the scene that we perceive, a representation of what is outside but by no means a simple internalization of it. The process is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Perception

The figure applies to all the senses, individually, so “perceptual” could be read as “visual,” producing images, or as “auditory,” producing sounds, among other possibilities. The perceptual output stage is the border between perceptual systems and higher level systems, particularly the conceptual. It represents the ultimate product of the perceptual processing – the sounds and images, that is – and is thus the immediate input to conceptual processing, which gives meaning to those products.

The existence of distinct perceptual and conceptual systems can be seen in two different types of agnosias (see Reference Behrmann and GoldsteinBehrmann, 2010; Reference Griffiths and GoldsteinGriffiths, 2010). Damage to parts of the brain that deal with conceptual processing can leave you with a clear image or sound but no idea what it is that you are seeing or hearing (associative agnosia). Damage to lower areas, on the other hand, can prevent the formation of a clear image or sound, making it difficult or impossible for the later processes to interpret it (apperceptive agnosia). Note also the bidirectional arrows in the figure, expressing the extensive interaction that occurs among the different systems.

The perceptual process is perhaps best understood through examples. Consider first the case of hearing a sound which you, being an expert on bird vocalization, recognize as the call of a marbled godwit. The air coming from the bird disturbs the air around you, producing vibrations in your ears. The auditory system constructs from these vibrations a representation for the sound “out there” and matches it with already existing sound representations. The candidates for this matching are contained in the store of sounds you experienced in the past – what can be called auditory output representations – one of which is the call of the marbled godwit. When this representation is activated, it activates a connected representation in the conceptual system, MARBLED GODWIT CALL. You have then perceived the call.

What about a bird call that you don’t already know? If you have never heard it before, there is no representation of its sound in the auditory store or its interpretation in the conceptual store. Auditory processing therefore creates a new auditory representation, using sounds that are already present. This new representation will then be connected to a conceptual representation. If you witness the bird making that sound, this new representation will specify that particular bird (the alternative would be a generic “bird sound” representation). You have then learned the sound that a particular bird makes.

We can now ask about the input to this learning. What exactly is it? One possibility is to identify the input as what is out there in the world, since that is what started the whole thing and is what the new representations are representing. But the new auditory representation that you acquire is the product of an elaborate construction process involving a number of intermediate representations (not shown in the figure), so maybe the input has to be placed between the bird and the output representation. The new conceptual representation is based on the auditory representation,Footnote 4 so maybe the auditory representation should be considered the real input to learning. Nothing is particularly wrong with any of these options – apart from the fact that each deals with only one part of the process. So maybe we should say the input is the whole perceptual process.

How we choose to apply the term “input” is rather arbitrary. The important point is that it is inseparable from the construction process and the individual representations involved in it. Also worth noting is the contribution of the visual experience, seeing the bird making noise. We could say it is part of the input, or that it provides the information needed to establish the conceptual representation; in other words, that it makes the input comprehensible.

4.2 Input, Perception, and Language

When we go from this simple example to language and language learning, extra complications come in, lots of them. But the basics of perception remain the same. What is distinctive about human language is that it adds a very rich means of connecting sounds (the output of auditory processing, that is) to concepts, allowing us to express an unlimited number of possible ideas and, more immediately relevant, to understand someone else’s expression of them. Figure 2 portrays the perception of language sounds (or written words).

Figure 2 Perception and language

Suppose during the bird noise someone says “That’s a marbled godwit.”Footnote 5 This event, out there, causes vibrations in your ears, which trigger auditory processing, culminating in an output representation of the sound of the utterance. To this point perception is essentially the same process as in the previous examples. If you didn’t understand English it could be almost entirely the same process: A conceptual representation would be directly constructed for the auditory output, perhaps consisting of the information that the sound was “something in English,” comparable to the concept in the previous example that you were hearing some sort of bird call.

Things are more interesting, though, if you can understand English or, especially, if you are learning to understand it. In this case processing will take a left turn at the auditory output. Specifically linguistic processes will deal with the sounds, constructing a sentence from them. Conceptual processes then form an interpretation for this sentence, just as they interpreted the bird sound (though with far greater complexity, of course). This linguistic-conceptual processing is carried out by systems having their own specializations, using the output of processing by the perceptual systems.

Note that the linguistic box in Figure 2 is labeled core linguistic knowledge rather than just linguistic knowledge. This is because of the non-monolithic nature of language described in Section 1. The core is the portion that is specifically responsible for the rich sound-meaning connections that make human language special.

At this point we can ask again: Where is “input” in this picture? The term could be used to refer to what is out there, or to any or all of the intermediate steps in the processing, or to the process as a whole. All can be useful ways of talking about the phenomena. Problems arise when we think that input is some real “thing” that needs to be pinned down. The important point is that input is inseparable from perception and therefore shows all the general characteristics of the perceptual process: multi-step construction carried out in terms of already-existing representations (linguistic and other). And it is this construction process that sets up learning and makes it possible.

4.3 Language in the Mind

The previous examples referred to different components in the mind – auditory, visual, conceptual, core linguistic – reflecting the fact that a complex system, such as the human mind, is necessarily composed of interacting parts. These parts represent different types of knowledge, encoded in different ways, associated with different types of processing. In order for the system to function properly, these various aspects of its operations must be segregated in some sense, so that a new face for example is processed as a face and not as an algebraic formula or a string of phonetic features or some mixture of these and other types of knowledge. In the brain this can mean that faces occupy a particular regionFootnote 6 and/or that face representations have especially strong connections to one another and to the lower-level visual features that are used in their construction. A central question for research and theory is the nature of the segregation: What exactly are the parts of the system? How do they interact?

The parts, whatever they may be, are often referred to as modules, and when we seek to understand their nature we are studying modularity. Many would avoid these terms, but in a broad sense everyone accepts the idea behind them. The system simply could not work without some sort of segregation of the knowledge types and the processes that construct and work with each type. Important disagreements involve the nature and extent of the segregation and especially the role of our genes – to what extent and in what sense are the modules innately determined? I will return to these questions herein.

When we talk about parts of the system, language is naturally taken to be one of those parts. Linguistic input is necessarily encoded in terms of linguistic features, and stored in a linguistic place. I use the term “place” in a loose sense, simply to mean that some sort of segregation exists. Given the non-monolithic character of language described earlier, it is actually more accurate to speak of places rather than place. Of particular importance here is core language, the knowledge that allows rich connections between sounds and meanings, as pictured in Figure 2.

What happens when there are two languages in one head? A second language has, necessarily, all the components of a first language. We also know that a bilingual’s two languages are intertwined, as seen in the ability of bilinguals to smoothly switch between their languages and merge them in rule-governed ways within a conversation. Research has shown that when a bilingual is using one language, relevant elements of the other are automatically activated, meaning primed for use (for reviews, see Reference Brysbaert and DuyckBrysbaert & Duyck, 2010; Reference de Groot, Starreveld and Schwieterde Groot & Starreveld, 2015; Reference Kroll, Gullifer, McClain, Rossi, Martín and SchwieterKroll, Gullifer, McClain, Rossi, & Martín, 2015; Reference Schwartz and SchwieterSchwartz, 2015). A reasonable interpretation is that the two languages are stored in the same “places.”

The conceptual system has a special status. Unlike visual, auditory, or linguistic systems, it is not dedicated to one type of function but is rather a very general, multi-function system, which is to say we can acquire abstract conceptual knowledge of virtually any type. What all the types have in common is that they are represented in the abstract, domain-general format of concepts. Readers familiar with research on memory might note the resemblance to declarative memory – the kind of knowledge that we can, at least in principle, describe and talk about. I will return to this point later.

The conceptual system’s ability to acquire abstract knowledge on virtually anything naturally extends to language. The knowledge acquired in a linguistics class is an obvious example. More interesting here is the knowledge acquired in a grammar-oriented second language class. Knowing that the past participle verb form is used in English passive sentences is not fundamentally different from knowing that Ouagadougou is the capital of Burkina Faso. Both are instances of abstract conceptual knowledge. What makes the language-related knowledge different is simply that it is about language. This is the metalinguistic knowledge described earlier (1.1)

4.4 Changing the Places in the Mind: Learning

Learning from input means making changes in the places where the processing occurs. Returning to the bird-call examples, if you were one of those benighted individuals who had never heard of a marbled godwit, the linguistic-conceptual processes would form new representations – linguistic and conceptual – to accommodate the new word. This is what sets up learning.