LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this article you will be able to:

• explain the principles of values-based practice, including its theoretical approach and practice skills

• use history taking to elicit the context of the symptoms and the concerns, preferences and expectations of patients, with improved awareness and proficiency to help them change their personal narrative and move towards recovery more effectively

• understand more about the relevance to clinical decision-making of one's own personal history and values as a clinician and recognise that some of the values at play in clinical decision-making come from the history of psychiatry.

Evidence-based medicine (EBM) can provide us with the odds ratios of treatment response or remission or the percentages of patients who will develop certain side-effects for various treatment options. In some situations, this might be perfectly sufficient to make a good clinical decision. It is, however, rarely so simple. For example, there may be several treatment options and one treatment might be more likely to be effective than others but also carry a higher risk of side-effects, or its side-effects might be particularly severe or irreversible. People are likely to attach different values to each of these options. For some, getting better from the mental health symptoms is more important than not having side-effects; certain side-effects may be more acceptable to certain people, and so on. So, how do you choose the treatment that will be best for your patient?

We probably all have faced similar difficult clinical decisions before, when knowledge of the relevant randomised controlled trials or meta-analytic studies did not really help us to know what to do. This is where you and your patient would start to be guided also by your own respective values. This is where values-based practice (VBP) comes into play.

If someone can tell us what is right, we usually feel that we know what to do. This tends to work well for the natural sciences (where often there is just one right answer) but often not so well in clinical practice. This is due to a number of factors. The first one I have already described: in clinical practice there are often multiple choices with significant diversity in the values attached to each. Also, certain elements of medicine are not driven by exact science but by the personal experience of the patient and the clinician, the history and traditions of the specialty, current codes of practice and cultural influences, all of which relate to the values of those involved. To be able to apply science to clinical practice skilfully, we need to be familiar with these values. Our knowledge of the relevant values, and the ability to work with them effectively, can help us facilitate a good process that enables the patient and the clinician or clinical team to make decisions that they can accept and own.

What is VBP?

Values-based practice (VBP) is a framework of clinical theory and skills to facilitate good process in everyday clinical decision-making. The starting point in VBP is respect for differences (Woodbridge Reference Woodbridge and Fulford2004). This does not mean that all things are acceptable: framework values are limits beyond which none of us would be prepared to go. These are the values that are genuinely shared between all of us (e.g. doctors cannot be expected to perform an intervention that they believe would be harmful to the patient's health, even if the patient is asking for that intervention to be carried out). Good process refers to, among other things, the inclusion and balancing of the values of those involved in the clinical decision-making process, similar to a political democracy.

VBP provides ten key pointers to good process (Woodbridge Reference Woodbridge and Fulford2004) (Box 1). These include four practice skills: awareness, reasoning, knowledge and communication. Awareness in this context is the skill to recognise that values are at play in a clinical situation even when it is not obvious (this is sometimes referred to as ‘value blindness’). Another practice skill is the ability to apply reasoning to explore values. VBP, similar to quasi-legal bioethics, deploys a variety of methods, including case-based and principle-based reasoning, utilitarianism and rights-based reasoning, but always in order to open up value perspectives rather than to close them down by establishing the ‘right’ values to have in a case. In VBP, unlike in quasi-legal bioethics, differences of values, while indeed sometimes requiring resolution, may also be a positive resource for clinical decision-making. Knowledge of values refers to knowing what values may be in play in a certain clinical situation. This knowledge can be gleaned from a variety of sources and include the value perspectives of all those involved in the clinical decision making process, not just the patient. Communication in VBP includes balancing different value perspectives and resolving conflict.

BOX 1 Ten key pointers to good process in clinical decision-making

Practice skills:

• awareness

• reasoning

• knowledge

• communication

Service delivery:

• user-centred

• multidisciplinary

VBP:

• the ‘two-feet’ principle

• the ‘squeaky wheel’ principle

• scientific advances increase the complexity of values

Partnership

(Woodbridge Reference Woodbridge and Fulford2004).A values-based approach to service delivery would support models that are user-centred and make good use of being multidisciplinary. A user-centred service is responsive to the values of its users (i.e. patients and their carers) and it uses the different value perspectives that members of the multidisciplinary team (MDT) bring to the case both in terms of in its understanding the patient and in deciding the treatment offered. In other words, if a team represents different value perspectives, they are more likely to be able to work with the equally different value perspectives of their patients.

The ‘two-feet’ principle refers to medical practice standing on two feet: facts (evidence) and values. The ‘squeaky wheel’ principle brings attention to the fact that values become more apparent when there is a problem. In healthcare, scientific advances increase the complexity of values and also the complexity of the evidence. When there is no treatment available, there is no choice. With the increasing number of choices science creates, there is usually an increasing role for values to enable a decision.

Finally, clinical decisions should be made in a partnership between those who are directly concerned, not by ‘outside experts’. VBP, although it involves partnership with ethicists and lawyers, puts the decision-making back where it belongs, i.e. with the patients and clinicians involved in the case.

How does VBP fit with current practice?

Spending time on the above can be useful in clinical practice in many ways, from increased patient and carer satisfaction, through better treatment adherence, to better staff retention. However, one might ask, how is VBP feasible in the current climate? How does it fit with current trends in medical training and clinical practice in the UK, increasingly dominated by targets, guidelines, codes of practice, manualised medicine, care pathways and packages of care?

Tending to patients’ concerns, preferences and expectations has always been part of good medical practice. Having the theory and skills supporting this organised into a framework with multidisciplinary input on both a theoretical and a practical level is relatively new but truly relevant to our present-day working practices. VBP principles have become part of the narrative of health and social care practice (Woodbridge-Dodd Reference Woodbridge-Dodd2012). The need to embrace the core principles of VBP such as patient-centred care, cultural competence, patient choice and co-production (patients (and their carers) making decisions about their treatment and care together with health professionals as equal partners) is very much present in current thinking in the National Health Service (NHS) (e.g. Local Government Association 2017; NHS England 2020). The curriculum set by the Royal College of Psychiatrists and approved by the General Medical Council (GMC) for core training lists many of them among the intended learning outcomes and the curricula for specialist training require trainees to demonstrate an understanding of VBP (Royal College of Psychiatrists 2020). Accordingly, an increasing number of publications is now available to facilitate learning (e.g. Woodbridge Reference Woodbridge and Fulford2004; Fulford Reference Fulford and Radden2007, Reference Fulford, Peile and Carroll2012). VBP principles are part of the fundamental standards set by the Care Quality Commission (2017) and a report commissioned by the GMC also recognises the ability to navigate conflicting values as a senior medical leadership quality (Shale Reference Shale2019). Psychiatrists at consultant level are senior clinicians expected to have the ability to recognise, communicate and resolve conflicts related to values.

How can we learn more about the values that play a role in clinical decision-making?

The first step in VBP is simply to recognise that values are at play in the clinical situation being considered.

But what are values and how can we recognise them? A simple, short definition would be that values are things or actions that are important to us. Values can be expressed in various logical forms, such as needs, wishes and preferences. In healthcare, these could present as concerns, preferences and expectations about the interventions and care provided by the clinician or the team. Our values can come from our life history and who we have become as a result of it, what profession we work in and what culture we live in.

In VBP, the first call for information is the perspective of the patient or patient group. There is a rapidly increasing knowledge base out there to help with this, including collections of first-hand narratives, ethnographic studies and social science research from anthropology, history, law and politics with a focus on mental health. The diversity of relevant values can also be grasped from media reports, literature, theatre and film portrayal of mental ill health. There are also philosophical methods that can be used to understand the values present in the patient's narrative. These include linguistic analytic philosophy, hermeneutics, discursive analysis and phenomenology.

However, relevant to our argument, VBP also takes into consideration the values of the clinician. It is easy to see that it may be less difficult to understand the patient's value perspective if we understand our own. But where do our values as psychiatrists come from? We develop our values during the entire course of our life. We bring them from our personal histories as sons/daughters, brothers/sisters, fathers/mothers, friends and doctors. They are shaped by influences from those close to us and the culture or cultures we have lived in. And some are rooted in the history of our profession.

History taking is important in every specialty, but it is really at the heart of psychiatry. From a VBP perspective, it is possible to conceive of three distinct meanings to it:

• exploring the history of the patient, similar to how we do it elsewhere in medicine. This includes the history of the presenting complaint, medical history, family history, personal history, etc., as every part can reveal important information about the patient's values and can have implications for treatment choice, treatment adherence and so on;

• developing an understanding of how our own personal history affects our own value perspectives; and

• becoming aware of the history of psychiatry itself, which shapes our attitudes and expectations as well as those of the patient and society.

The patient's personal history – why is it important?

It is of course important for the facts gathered from it (and how the patient and the clinician see these), but it is also an essential tool in establishing rapport (Andrews Reference Andrews2006) and an empathetic understanding of the patient.

As Arlene Bowers Andrews (Andrews Reference Andrews2006) points out, the helping professions, among which, apart from medicine, nursing, psychiatry, psychology, counselling and social work, she also includes ministry and law, have a long tradition of exploring and working with social histories as a tool to promote healing and growth, and, in our context, recovery. Studies from fields such as anthropology, sociology, genetics, criminology, psychology, social work, education, journalism and history demonstrate the strong influence that meaning and context can have on individual development and human behaviour (Andrews Reference Andrews2006).

The role of context

Eric Chen provides us with powerful arguments about the importance of context in psychopathology (Chen Reference Chen, Marková and Chen2020). He points out the tendency in modern psychopathology to isolate mental symptoms from their sociocultural and personal contexts and the reasons for it. He observes that taking detailed histories became associated with psychodynamic approaches, although other disciplines aimed at understanding human behaviour have also made use of similar contextualised approaches, such as the method of ‘thick description’ in anthropology (Chen cites Geertz (1973)). He argues that the use of psychological theories became more restrained after discoveries about the high level of inheritance in many mental disorders, leading to a more ‘biological’ view of them, the so-called ‘brain perspective’. The use of questionnaires has become increasingly widespread in psychiatric research and questionnaires are ‘decontextualising instruments par excellence’. Chen convincingly argues that there is a risk in ignoring context, as symptoms are not static, they interact with life experiences and evolve. Ignoring their context may prevent understanding of the changes. He explains through examples how, in psychosis, knowing the psychosocial context helps us understand to what extent the symptom is a departure from the patient's expected experience. The context can also inform the prognosis; a symptom that emerges without an external stressor would be expected to be less likely to improve with changes in the environment. He warns that although, generally speaking, it is the content of a symptom that could be influenced by context and the form is supposed to reflect more ‘stable’ brain processes, this separation is not absolute, and form and content may interact with each other.

Working with the patient's personal narrative

The patient's narrative has always been important in all branches of medicine but has never taken centre stage quite as much as in psychiatry, both in diagnosis-making and in treatment. Bruner (Reference Bruner and Bruner1984) distinguishes between ‘life lived’ (milestones, critical incidents and key decision points), ‘life experienced’ (meanings, images, feelings, thoughts of the person) and ‘life as told’ (the unique personal narrative, which is influenced by the cultural conventions of storytelling, audience and social context). In a clinical encounter, ‘the life experienced’ is communicated through the ‘life as told’, which is especially intertwined with one's value systems. As Andrews explains, ‘Like any good historical research, the meaning of the social history emerges through skilled interpretation of the history, development of a subjective current understanding about the past, and application of this understanding to future action’ (Andrews Reference Andrews2006: p. 4).

A chapter on the psychiatric interview in The Maudsley Handbook of Practical Psychiatry explains that ‘The main goals are to elicit the necessary information to make sense of the presenting problems, to determine whether you are able to make a diagnosis, and to try and understand the origins of the presenting problems in a particular individual’ (Owen Reference Owen, Wessely and Murray2014: p. 2). It points to a ‘feature of the psychiatric assessment which, although important in other specialities, is more explicit in psychiatry, i.e. using the interview in obtaining a trusting relationship with the patient’. Quite rightly, it notes that patients will have a range of preferences. It suggests asking questions such as ‘Why has this patient presented in this way at this point in time?’ in order to develop a management plan that will fit the patient's needs. It highlights the importance of exploring the time course and evolution of the patient's problems, including the social milieu within which the patient developed the problems and the patient's thoughts as to what caused the symptoms. It also encourages checking with the patient that one's understanding of their presenting problem is correct. As regards the exploration of family history of mental illness, it suggests that ‘It is better to first display interest in the family before enquiring about the health of the family’. This, of course, takes time and several sittings may be needed. These are important recognitions. Unfortunately, there is relatively little guidance in most undergraduate and postgraduate curricula on the details of how to achieve these. This is the core business of VBP.

According to Andrews (Reference Andrews2006), the health professional listens to the patient telling his or her story, contributes their own interpretations, complements the personal narrative from other sources of information (other peoples’ views, previous records, etc.), uses knowledge and skills from theory, empirical studies and past experience, shares their interpretations with the patient and reflects carefully on their own interpretations in order to distinguish them from those of the patient. This is a joint hermeneutic activity, and, as Andrews also observes, the clinician becomes part of the story.

Woodbridge & Fulford (Woodbridge Reference Woodbridge and Fulford2004) describe a particularly challenging aspect of this joint work, calling it ‘the problem of two languages’. The patient may describe a personal desire, problem or event in ‘ordinary’ language. This is then translated by the mental health worker into ‘work’ language, such as ‘symptom’ or ‘social functioning’. The mental health worker may use ‘work’ language to communicate with the patient, using terms such as ‘assessment’ and ‘care plan’, which the patient has to translate back into ‘ordinary’ language. This often becomes a problem when a word has a very different meaning in ordinary language compared with medicine. For example, in the case of the word ‘depression’ the lay and medical meanings can indeed be very far apart, making the differentiation between sadness in a healthy person, low mood in severe depression and mood fluctuation in emotional instability challenging. Or the word ‘orientation’ in cognitive assessment has rather different connotations in everyday English, such as political or sexual orientation, or establishing one's position or direction relative to the compass. Without paying due attention to this, it can lead to at least two major problems. First, a substantial amount of meaning is lost in translation. Second, the doctor can inadvertently shape the way the patient thinks of his or her experience and thereby change their shared understanding about the nature of the patient's symptoms. For example, the patient may describe several of his neighbours saying awful things about him (as a thought) and the doctor, thinking in psychopathological terms, may ask him to tell her more about these voices, assuming that the patient is describing auditory hallucinations. One way to avoid this is to ask the patient to describe their symptoms in as much detail as possible before trying to categorise them in any way.

There are a number of other factors that may make it difficult at times to work effectively with the patient's personal narrative. Donald Blumenfeld-Jones (Reference Blumenfeld-Jones1995) distinguishes between ‘truth’ and ‘fidelity’. In his definition, truth is ‘what happened in a situation’ and fidelity is ‘what it means to the teller of the tale’. Andrews (Reference Andrews2006) rightly observes that, to ensure fidelity, the clinician needs to listen carefully to the unique perspective of the client (in our case, the patient) with cultural competence about the context. She warns us that ‘People may repeat family myths, those stories that have been passed from one generation to another that may have partial or no basis in fact but are believed by the family members’ (Andrews Reference Andrews2006: p. 10). Secrets can be too difficult to communicate or they can generate emotions that are too difficult to bear for those involved. People may also decide to withhold information to protect themselves or others. A special case is safeguarding, where the need for disclosure sometimes needs to be balanced against the patient's preferences. Informants are a useful source of collateral information and can contribute to the triangulation of evidence, but they have their own agendas and personal narratives and see the patient in that context. Exploring the patient's personal history in a psychiatric or psychotherapeutic context is a very special situation. Patients often say they have shared more with the clinician than with anyone else before about their lives, including some of the saddest and happiest moments, their greatest regrets and most intimate hopes. This is often an immensely powerful emotional experience and can have a liberating or destabilising effect on the patient.

As The Maudsley Handbook points out (Owen Reference Owen, Wessely and Murray2014), in psychiatry the interview can also have value as a psychotherapeutic intervention. With the help of the clinician, patients can explore painful past events and gain new insight into their problems. Importantly, during the process of exploring their history, they can change their personal narrative. This can enable them to develop more adaptive interpretations of their experience and to use healthier ways of coping. In other words, they can start moving towards recovery. Recovery in this context does not necessarily mean becoming symptom-free but tackling one's mental health problems with hope and optimism and working towards a valued lifestyle within and beyond the limits of any mental health problem (Woodbridge Reference Woodbridge and Fulford2004).

Exploring health-related values during history taking

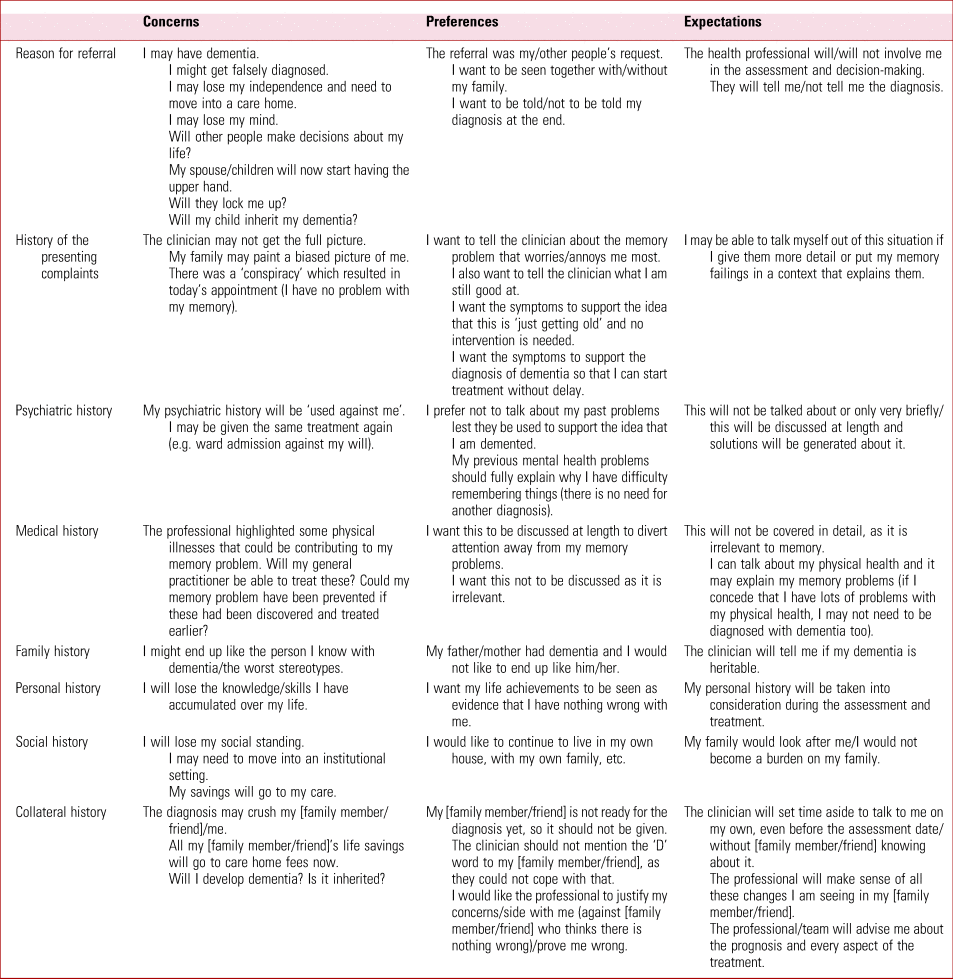

Various concerns, preferences and expectations can become evident when exploring the reasons for referral and patients’ medical history, personal or social histories. For example, patients (and clinicians!) tend to feel more uncomfortable if the referral was primarily the idea of someone other than the patient. Patients can have strong preferences about whether they would like a family member to be present when they are interviewed. Patients sometimes prefer not to be told their diagnosis; this may make the assessment less stressful for them, but it makes it much more difficult for the clinical team to support the patient and their family. An exploration of exactly what the patient means by not being told the diagnosis may reveal that their preference is not absolute. They could be, for example, perfectly happy to take a memory medication used in Alzheimer's disease, if indicated, they just would not want the word ‘Alzheimer's’ or ‘dementia’ to be used in their presence. Table 1 illustrates some of the values that might be at play during a memory clinic assessment.

TABLE 1 How the patient's (and their carers’) values might may shape the assessment process: an example from the memory clinic

The life history of the clinician

The life history of the clinician is a less discussed aspect of clinical work. Is it important? One once very influential movement certainly thought so: psychoanalysis. Although some registering bodies still require psychotherapy trainees to complete a certain number of hours of personal therapy, and cognitive analytic therapy, for example, makes use in the treatment process of the reciprocal roles played out between patient and the therapist, obviously influenced by the therapist's own personal history and values, the only psychotherapy school that really took the personal history of the therapist into account was psychoanalysis. So much so that therapists usually have to undergo personal analysis before being allowed to treat patients.

One psychoanalytic term still present in medical student and psychiatric trainee teaching is ‘countertransference’. It refers to feelings and reactions evoked in the clinician by the patient owing to the clinician's personal history and/or the patient's behaviour. Examining countertransference can be considered as a self-reflective activity (Adshead Reference Adshead2009). It is a powerful tool that can improve our understanding of our patients and our empathy.

A modern-day tendency in professional appraisal, licensing and continuing professional development (CPD) is the increasing requirement of clinicians to use reflection in their practice. The clinician's values (preferences, needs and expectations) are explored in this process. Although reflective practice includes examining one's own emotional responses to clinical situations and one's needs and preferences regarding the future, it is usually focused on one's clinical work and there is no explicit requirement to relate one's work-related values to one's own life history. One may, of course, find it helpful to do that alone or in discussion with a trusted colleague who has no managerial responsibility or conflict of interest, such as a mentor working elsewhere. Box 2 contains a number of examples of the type of questions one might want to explore.

BOX 2 Self-reflection: exploring the impact of one's own personal history

What were the key moments/influences that resulted in you becoming a psychiatrist?

Where did you do your undergraduate training and what was the attitude there towards psychiatry?

What motivates you at work? What would you like to achieve for your patients?

One source of information on how the personal history of the clinician can influence their professional practice is autobiographical writings of prominent personalities in mental health (e.g. Clark Reference Clark1996; Sternberg Reference Sternberg, Fiske and Foss2016) and biographies about them (e.g. Demorest Reference Demorest2004).

In his history of Fulbourn psychiatric hospital (Clark Reference Clark1996), David Clark writes eloquently about how his own life experiences shaped the values he held about psychiatry. Clark was appointed Medical Superintendent of Fulbourn Hospital at the age of 32 and worked in that capacity from 1953 to 1971. He was the son of a medical scientist and grew up in Edinburgh. He studied medicine at Cambridge and Edinburgh and qualified in 1943. He spent 3 years in the army before psychiatric training at the Royal Edinburgh Hospital with Sir David Henderson and then at the Maudsley Hospital in London under Sir Aubrey Lewis, where he underwent personal psychoanalysis and trained in individual and group psychotherapy under the founder of group analytic psychotherapy, S. H. Foulkes. Box 3 is an illustration of how the clinician's life experience can shape their values about clinical work using Clark's autobiographical account. Of course, not all of us have an extraordinary life like Clark did, but we all have our own significant life events, some happy and some upsetting, which influence what we regard as important in the way we relate to others, including our patients. Clark was instrumental in unlocking all wards at Fulbourn by 1958. In Box 4, he writes about how his relevant values influenced his decisions at work. Under Clark's leadership, Fulbourn became an internationally renowned centre of social treatment.

BOX 3 A clinician's reflections on how their own life events have influenced their values

‘During my time in the Army I did a limited amount of medical work. I trained as a parachutist and spent much of the time as a Section officer in a Parachute Field Ambulance leading a group of men into action; what was particularly valuable for me was that half my section were Conscientious Objectors, brave, intelligent but argumentative men who did not hesitate to question any order they doubted. I was with the armies that conquered North Germany in 1945 and saw the abominations of the Nazi Concentration Camps. Later in 1945 I was sent to the Far East and for three months was in charge of a camp of 2000 Dutch civilians in the jungles of Sumatra […] having to negotiate with the Dutch and their former jailers, the Japanese, to prevent a massacre by the Indonesian nationalists. These experiences taught me something of the perils and responsibilities of command, as well as showing me many of my own personal limitations. They also showed me the abominable things people would willingly do to one another and left me with a deep distaste for locking anybody up.’

(From Clark Reference Clark1996, p. 39; italics added)BOX 4 A clinician's reflections on how their values have influenced their clinical work

‘My motives for applying for the Fulbourn job were mixed. I was married, with three young children and I wanted the security of the Consultant post. […] I also had an enduring desire to do something to improve the lot of the long-stay, back-ward patients. In my early days in mental hospitals, I had felt deeply concerned for these patients; I had seen them left, neglected, to their hallucinatory ramblings, or worse, locked up in padded rooms, straight-jacketed or mistreated by staff because of their violence. […]

I did, however, have strong ideas, feelings and beliefs which I wanted to try out. In the Army I had been impressed with how men's psychological health could be influenced by the way in which they were led. In my psychiatric training I had been struck by the difference between patients in demoralised, static hospitals and those in hospitals that had lively, vigorous and hopeful leadership.’

(From Clark Reference Clark1996, pp. 39–40; italics added)Is there any empirical research out there about the influence of personal history on the work of the clinician? The concept of the ‘wounded healer’, i.e. that personal experience of illness can usefully influence one's therapeutic endeavours towards others, has been around for a long time (Jackson Reference Jackson2001). One popular research situation has been when the clinician has the same condition as the patient. There is less literature about the effect of the clinician's life history in general.

Personal history of migraine, for example, leads to a more somatic view of migraine as a disorder and to different treatment recommendations compared with self-treatment (Evers Reference Evers, Brockmann and Summ2020). General practitioners’ treatment choice for depression is influenced by gender, personal history of psychotherapy or antidepressant treatment, and history of depression in someone close (Dumesnil Reference Dumesnil, Cortaredona and Verdoux2012). Psychiatric, psychology, paediatric and social work professionals responsible for evaluating child sexual abuse allegations who had been sexually or physically abused were more likely to believe allegations of sexual abuse contained in 16 case vignettes (Nuttall Reference Nuttall and Jackson1994). A special case is peer support workers. Their input in mental healthcare has been shown to reduce hospital readmission rates, in-patient days and costs and to increase quality of life outcomes (Mental Health America 2018) and has benefits for peer support workers themselves (Mental Health Foundation 2020).

The history of psychiatry

The values of both the patient and the clinician are also influenced by history at a collective level: the history of psychiatry.

Medical practice never happens in a vacuum, it is always embedded in the cultural context of the era, which influences what we regard as pathology or what can be considered as treatment – appropriate treatment or humane treatment. The following is an extract from the Earl of Hardwick's speech at the laying of the foundation stone of Fulbourn Asylum in 1856. Talking about the care of lunatics in the past, he said:

‘for some time their condition was regarded as incurable, and their acts were sought to be restrained by rules and violent means. The great advancements made by medical professors has convinced the public that insanity is not incurable; and that although there are idiots whose minds are entirely gone, in most cases the patient can be restored to mental soundness’ (Clark Reference Clark1996, p. 8).

Although the founders described a rather large change in the expected prognosis (and values), we know from the records that the reality for most, if not all, turned out to be different until the 1950s. As an old age psychiatrist I still frequently find a strong fear in my elderly patients about even having an out-patient appointment in Fulbourn, more than a 150 years on from the foundation of the Fulbourn Asylum – when you were ‘carted off’ to Fulbourn, it was rare that you would ever go home again. Although the asylum as a model is long gone, the idea that coercion can be necessary in certain situations is still very much present.

An important factor influencing the values of the general public, which includes our patients and carers, is the gap or time lag between public understanding and actual current practice in psychiatry (Dudas Reference Dudas, Marková and Chen2020). Public understanding seems to reflect earlier practice or, sometimes, simply an inaccurate image. A significant proportion of patients and carers have misgivings about psychiatry and some are decidedly critical of it. It is reasonable to assume that many of the current criticisms have been the result of viewing past practices retrospectively, taking them out of their historical context and comparing them with our current standards.

By contrast, the historian tries to understand the past in its own context. Claire Hilton, the Royal College of Psychiatrists’ resident historian, uses the example of ‘malaria inoculation’ (Hilton Reference Hilton2019). It was a dangerous but commonly used curative treatment for general paralysis of the insane (a manifestation of neurosyphilis). Julius Wagner-Jauregg was awarded the Nobel Prize for his discovery of it. Hilton points out that a retrospective, hindsight analysis would discredit the treatment, whereas a historical analysis that explores the context, including the prevailing values, attitudes and the choices available at the time would not. Clark describes asylums as places where the main task was the control of physical violence (Clark Reference Clark1996). Another of Hilton's examples is the Mental Treatment Act 1930. Looking at it retrospectively one could find a lot to criticise about it, but using a contextualised historical view, one would find it easier to see how it aimed to reduce stigma through replacing the term ‘asylum’ with ‘mental hospital’ and introducing the option of ‘voluntary’ admission.

Conclusions

Values play an important role in clinical decision-making, and history taking is a good source of information about values.

Although exploring what is important for the patient while taking the patient's history has always been part of good clinical practice, relatively little explicit guidance is available in the medical literature about how to do it. History taking, if done well, offers an opportunity to understand the context of the patient's symptoms, their interpretations of them, and to help the patient change their personal narrative in an adaptive way.

Exploring the history of the clinician was important for one school of thought in psychiatry, but less attention is paid to it in current practice. Values-based practice places emphasis on taking into consideration the values of both the patient and the clinician in clinical decision-making. The clinician's history is a good source of information about his or her values.

Some of the values exerting an influence on clinical decision-making come not from the personal histories of the patient and the clinician but from the collective history of the profession, the history of psychiatry. VBP provides useful methodology for working with all these values.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Professor K.W.M. Fulford, Dr Emad Sidhom, Dr Julia Paraizs and the Values-Based Practice Special Interest Group at the Cambridgeshire and Peterborough NHS Foundation Trust for their helpful comments on earlier versions of this article.

Author contribution

This article is the work of Robert B. Dudas.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of interest

None.

An ICMJE form is in the supplementary material, available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bja.2021.45.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

1 The practice skills of VBP enable the clinician to do all of the following, except:

a becoming more aware when there are differences of values behind difficulties in practice

b identifying the ‘right’ values to have in any situation

c communicating effectively to open up the value perspectives of those involved in clinical decision-making and resolve conflicts between values

d having an understanding from a variety of sources about the values that may be at play when these have not been/cannot be explored directly with the patient or others involved in the case

e reasoning better about values with the patient, their carers and other health professionals.

2 In addition to gathering the facts, taking the history of the patient is also an opportunity to:

a build rapport and an empathetic understanding of the patient

b understand their interpretation of their symptoms and compare it with one's own

c elicit their concerns, preferences and expectations

d help the patient change their personal narrative and develop more adaptive interpretations of their experience as well as healthier ways of coping

e all of the above.

3 Exploring the context in which the patient's symptoms developed is important because:

a the psychosocial context helps us understand to what extent the symptom is a departure from the patient's expected experience

b symptoms are not static, they interact with life experiences and evolve

c the context can inform the prognosis

d the context can also inform research

e all of the above.

4 Countertransference:

a should be avoided if possible

b involves strong feelings in the patient towards the clinician

c is no longer relevant in clinical practice

d can be a useful source of information and improve our understanding of the patient

e is always a result of transference.

5 The historian of psychiatry:

a compares past practices against current standards

b ignores the historical context, including the prevailing values, attitudes and the choices available at the time

c tries to understand the past in its own historical context

d does not submit their work to any peer review

e often chooses their subject of inquiry on the basis of personal or family grievance or trauma.

MCQ answers

1 b 2 e 3 e 4 d 5 c

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.