European Commission, Directorate General for Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship, and SMEs, “CE Marking,” accessed May 2021, https://ec.europa.eu/growth/single-market/ce-marking_en.

Its contours are widely recognizable, but the “CE mark” appears with such ubiquity and is so deeply embedded within our collective visual memory that we think little about its significance. By indicating conformité européenne to regional standards for health and safety, the symbol serves several important functions: it is equally a source of consumer confidence in a product's regulatory compliance and a mechanism for a kind of regional “nation branding,” a logo “in the promotion of [the EC's] interests in the global marketplace,” and a visual reminder of the far-reaching influence of Brussels and its rule makers.Footnote 1 Most importantly, marks of conformity like the CE mark function dually as vectors for the circulation of goods within and among markets, on the one hand, and as non-tariff barriers restricting market access, on the other. In the case of European markets, the small CE emblem effectively determines what products in key categories such as electronics and machinery can legally be sold within the European Economic Area (EEA)—the trading bloc formed between the European Union (EU) and European Free Trade Association (EFTA) in 1994. As a result, this seemingly mundane icon of technocracy is actually at the center of the relationship between business and governance in Europe and represents the most fundamental building blocks of political economy, shaping everything from the macroeconomy of international trade to the microeconomy of household goods.

For all of its contemporary consequence, relatively little scholarly attention has been paid to the origins of CE marking, the system of conformity assessment and certification that includes affixing the emblem of the CE mark.Footnote 2 Yet, its centrality to the free movement of goods across the EU's Single Market and the EEA, as well as its ability to restrict the market access of goods and their manufacturers, underscore the importance of historicizing its development and examining the stakeholders involved in shaping its procedures.Footnote 3 The European Commission's “New Approach” to standardization—initiated in 1985 amid hurried efforts to relaunch integration and complete the Single Market—streamlined the process of removing technical barriers to trade by focusing only on “essential requirements” outlined in directives drafted by the European Commission and approved by the European Council. The New Approach delegated the development of standards to European standards bodies, kept the use of standards voluntary, and granted presumed legal conformity to products manufactured according to European standards.Footnote 4 While the New Approach lacked comprehensive procedures for testing and certifying conformity, subsequent European Commission directives for pressure vessels, toys, and construction products issued in 1987 and 1988 implemented a common mark of conformity, although they did not address the persistent patchwork of heterogeneous national systems. In 1989, after consultation with industry and business groups, the Commission's “confusingly named” Global Approach to Certification and Testing provided three major reforms.Footnote 5 It created comprehensive operational categories called “modules” for conformity assessment (the set of processes that demonstrate a product has met the requirements of a standard), consolidated the certification of conformity (verification that the legal requirements have been met), and required a universal mark of conformity for all products covered by New Approach directives: the “CE mark.”Footnote 6

How did businesses respond to the development of regional standards, essential requirements, and various systems of conformity assessment and certification? Did companies headquartered in the EC express interests that differed from those of their counterparts based elsewhere? How does the history of CE marking and its wide application inform our understanding of the business experience of integration by standardization, and what does it tell us about the dynamics of business-government relations across the European region? Motivated by such questions, this article examines the origin, implementation, and reform of the CE marking process and considers the perspectives of both policymakers and companies in developing a common system of testing and certification. Archival documents from European institutions make it possible to reconstruct exchanges between business groups and the European Commission and European Parliament and reveal that the EC solicited business feedback as it worked to develop and refine its Global Approach.Footnote 7 Because CE marking shaped the regional business environment and was the result of a public-private effort, this dialogue between business and policymakers is an essential, but understudied, chapter in the history of European standardization and market integration. And because of its application beyond the borders of EC member states, the development of CE marking occupies a central place in the wider economic history of European integration, from the EC to the EEA.Footnote 8

This article makes three main contributions. First, it considers the role of CE marking in European economic integration. In doing so, it finds that the process of conformity assessment and certification was crucial to internal market integration in the EC, advanced the competitiveness of European firms, and compelled extra-EC companies to adopt European standards in order to gain access to the region's large Single Market.Footnote 9 But common standards also presented challenges to firms operating in Europe.Footnote 10 As a second contribution, then, this article examines the ways standards and regulations shaped business environments, especially for firms producing and selling products in the key categories for which the EC issued directives. Essential requirements and rules for conformity assessment and certification had the potential to facilitate economies of scale just as much as they had the potential to create new barriers to trade.Footnote 11 As a result, businesses were eager to ensure that regional standards would not present market obstacles. This article's third contribution is its analysis of the ways business groups shaped the regulatory environments in which they operated by contributing to the development of the Global Approach to Testing and Certification. Interpretations of this history need not sensationalize the influence of business on policy in order to acknowledge that the increasing, global “privatization of regulation” augmented the “power of standards” and certification and only made firms more committed to close involvement in the standards process, motivating European multinationals and exporters to the EC to advocate for Europe's adoption of international norms.Footnote 12 Filling the gap in scholarship on both CE marking and business responses to it, this public-private history gives us purchase on the evolution of business-government relations in Europe and on the ways conformity assessment and certification shaped production, consumption, and regulation across the region.Footnote 13

To contextualize its interventions, this article begins by historicizing the foundations of European standardization and surveying the achievements and shortcomings of the Commission's “old approach” to technical regulation, in use from the 1960s to 1980s. In its second section, the article discusses the New Approach and its role in relaunching the process of market integration among EC member states in 1985. The weaknesses of the New Approach and the need for reform are discussed in the third section, along with the European Commission directives from 1987 and 1988, which introduced a mark of conformity. The fourth section turns to the drafting of the Global Approach and the contributions of business to developing its modules and CE marking procedures. The fifth section connects the development of CE marking to the completion of the Single European Market and the creation of the EEA. The conclusion reflects on the implications of this history for conceptions of European integration and of the ways business related to the rules of the Single Market and the broader European area.

Early European Standardization and the “Old Approach”

The roots of European standardization lie in the late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century globalization of ideas, trade, and norms. World War I shocked the trend of increasing global interconnectedness and creation of international standards, but by the interwar period, the League of Nations imagined new frameworks for economic cooperation, and organizations like the International Chamber of Commerce advocated for trade liberalization with common rules.Footnote 14 Such internationalist aspirations were soon stymied again, as much by the uneven development of the Second Industrial Revolution and the failed management of the peace as by the outbreak of another world war.Footnote 15 Yet, early proposals for international economic coordination paved the way for postwar designs for a new world order in which economic integration could finally guarantee stability.Footnote 16 As wartime nationalism gave way to intensive international cooperation after World War II, organizations emerged with improved plans for widespread social and economic coordination.Footnote 17 These proposed “internationalisms” required institutions to facilitate their objectives, and so sprung up a vast network of organizations like the United Nations (UN) and its economic commissions, the Council of Europe, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), and, out of the European Coal and Steel Community, the European Economic Community (EEC), the early predecessor of the EC and EU.Footnote 18

The many and diverse iterations of integration—ranging from cultural essentialism to political federalism to economic unification—shared a core element: the need for common norms and standards and the demand for an apparatus to coordinate harmonization. While “globalists” saw standards at the intersection of the worlds of dominium and imperium, capable of forging a world economy through the use of uniform technical specifications for goods on an international market, international standards garnered widespread support from those with regional and even national interests who saw standards as engines of widespread economic growth, the means by which producers could achieve economies of scale.Footnote 19 That the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) was established in parallel with the UN and EC in the mid-1940s and came to occupy a prominent place within the concentration of international organizations in Geneva and to provide standards documents to its fellow intergovernmental organizations proves just how central standardization was to the global project of economic integration.Footnote 20

As the European project took shape in the 1950s and western European countries developed their own more insular internationalism, standards acquired a new importance. They became mechanisms for integration through the removal of barriers to trade and, equally, for reinforcing the exclusivity of the EEC agreement for a common market made between France, Germany, Italy, and the Benelux countries in the 1957 Treaty of Rome. Articles 30 and 100 of the EEC treaty focused on the legal and policy regimes for legislative harmonization, the purpose of which was to overcome national differences impeding cross-border trade: Article 30 allowed for restrictions on imports, exports, and goods for reasons of security, morality, and human health and safety; Article 100 gave the European Council the power, after receiving a proposal from the European Commission and consulting the Economic and Social Committee of the Parliament, to issue directives for the approximation of legislation across member states.Footnote 21 High-quality standards offered the promise of expedient legislative harmonization. But the EEC lacked an effective apparatus to utilize voluntary standards as a means of technical harmonization.Footnote 22 Meanwhile, several European countries interested in free trade but not in the EEC's uniform tariff—namely Austria, Denmark, Norway, Portugal, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom—formed the European Free Trade Association in January 1960.Footnote 23

It was in this dual context of the EEC on one side and the EFTA on the other that “standards entrepreneur” Olle Sturén, a Swedish engineer, spearheaded the creation of the Comité européen de normalisation (CEN) in 1961, an organization that could unite the “inner six and outer seven” around the shared goal of free trade in the region.Footnote 24 CEN's mission was, from the outset, to promote open trade across the continent through the development of common standards.Footnote 25 It was designed to receive input from a variety of stakeholder groups, including European companies, governments, and, most importantly, the national standards bodies on whose cooperation the organization relied. In fact, the regional body acted as something of a clearinghouse for national standards, as well as a forum for discussion and negotiation between national bodies like the DeutschesInstitut für Normung (DIN), the Association Française de Normalisation (AFNOR), and the British Standards Institution (BSI).Footnote 26

In 1966, the French government proposed a partnership with the Federal Republic of Germany to create a Franco-German committee on standardization.Footnote 27 The Germans agreed, with the caveat that the United Kingdom be included as well, thus forming the Tripartite Committee on Standardization, a subgroup of CEN aimed at accelerating the larger group's progress toward harmonization.Footnote 28 Meeting two or three times per year, the committee tackled such topics as auto safety standards and juridical frameworks for standards enforcement, and it made agreements about norms for key items like office equipment and machine tools.Footnote 29 In 1971, on the eve of the EC's first enlargement to include Britain, Ireland, and Denmark, the UK delegation to the tripartite committee urged that “it was now essential to get the CENEL harmonized system into full operation (in the sense of putting components on the market) as quickly as possible.”Footnote 30 In addition to the “preparation of harmonized specifications,” this objective required “the establishment of an internal Mark of Conformity.”Footnote 31 A mark would indicate to consumers across the enlarged common market that a product had met the EEC's specifications. While the committee failed to advance the idea of a conformity mark any further at the time, this early proposal for a certification of conformity to regional standards laid the first layer of a foundation for what would eventually become CE marking.

Despite these supplementary initiatives to accelerate regional normalization, and despite early calls to formalize conformity assessment to regional standards, CEN made only modest progress during the 1960s and 1970s. A few achievements stand out, though. Amid the global race in computing of the early 1970s, and building on early predecessor organizations for electrotechnical standards,Footnote 32 the highly strategic electrotechnical sector developed a more cohesive regional standards organization called CENELEC in December 1972. As with CEN, membership in this expanding genealogy of electrotechnical standards organizations included EFTA members from the start, and the objectives were to promote intraregional trade and cooperation among European tech firms, which were increasingly feeling pressure from their American and Asian rivals. CENELEC benefited from being focused on fewer, more specific objectives than CEN, and it provided the first opportunity for centralized European interests to set the standards agenda for the ISO and the International Electrotechnical Commission.Footnote 33 Fueled by the momentum generated by the creation of CENELEC, the most significant breakthrough in regional standardization came just a few months later when the European Commission issued the Low Voltage Directive (73/23/EEC) of 1973.Footnote 34 This “ancestor of regional directives for technical specifications” paved the way for the EC to take the lead on standardization for the entire region in the years that followed, although nearly a decade would pass before the next major milestone.Footnote 35

During this period of the 1960s and 1970s, the Commission's approach to technical regulation in the EC proved inefficient. It strove to remedy the heterogeneity of requirements among member states through harmonization, replacing national rules with European ones. But its efforts to independently determine what specifications were needed to harmonize goods across member states was hierarchical, fastidious, and arbitrary.Footnote 36 Furthermore, its preoccupation with matters internal to the EC precluded closer collaboration with CEN, which was committed to broad regional cooperation. Because the Commission included very detailed prescriptions in proposed EC legislation, the Council found it difficult to reach any agreements at all.Footnote 37 This “old approach” was “cumbersome, unrealistic, redundant in its disjointedness from standards, slow, poorly implemented, of low priority to the Council, out of touch with the realities of global trade, and, crucially, had utterly neglected issues of conformity assessment and testing.”Footnote 38 National bodies, each with its own unique assessment criteria and procedures, were responsible for testing product conformity to the new European norms, which they did with wide variation. As a result, the old approach represented a great deal of work with dismal results. Not only were proposed common regulations already outdated by the time member states finished fighting over them, but economic pressures motivated national governments to develop economic policies designed to isolate and protect firms in their own markets, widening the chasm between member state legislations even more and further obscuring the promise of market integration in the EC.

A New Approach to Market Integration

When the crises of the 1970s gave way to the increasing challenge of globalization in the early 1980s, national governments—who had agreed to increased liberalization through the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) as a means of ensuring economic growth—also implemented protectionist measures to shore up their economies from competition. Liberal trade agreements prohibited the erection of tariff barriers, but states such as France and Italy initially erected non-tariff barriers (NTBs) like voluntary export restraints (VERs) to exclude foreign firms from their market.Footnote 39 Such measures both impeded cross-border European business and reversed the Commission's efforts to integrate EC member states by eliminating NTBs. It became clear to both the business community and regional policymakers that Europe's economic survival required the elimination of internal barriers as much as increased economic growth. The European Court of Justice's ruling in the Cassis de Dijon case in 1979 had set the legal precedent for mutual recognition of standards, allowing goods produced according to the regulatory guidelines of one member state to circulate lawfully through the others.Footnote 40 Yet, even if the narratives of “Eurosclerosis” neglect some progress made during the 1970s, it is true that in the realm of standards quite little had been accomplished within the EC since the customs union was completed in 1968.Footnote 41 Non-tariff barriers to trade persisted, impeding the realization of the original goal of an internal market.

In the early 1980s, the Commission proposed that the EC should establish a procedure to coordinate standards and regulations on a regional level to prevent the rise of new technical barriers. The Mutual Information Directive (83/189/EEC), passed in March 1983 and implemented on January 1, 1985, became the primary mechanism by which the EC could coordinate national legislative developments among member states.Footnote 42 With this directive, the Commission began to view the regional standards bodies CEN and CENELEC as partners in the harmonization process with the information on national technical specifications the Commission so desperately needed in order to eliminate barriers to trade. Notably, just like the Commission, the Secretariat of the EFTA also agreed to cooperate with CEN/ELEC in 1983. Also, in April 1984, the EC and EFTA signed the Declaration of Luxembourg agreement, providing for the free circulation of goods among the two groups.Footnote 43 In conjunction with this agreement, the EFTA developed its Committee on Technical Barriers to Trade, which began meeting regularly with the Commission on matters of harmonization and standards in industrial policy.

Building on this momentum, the Commission produced a white paper in May 1985 that enumerated concrete proposals for “completing the internal market” through a “New Approach to Technical Harmonization and Standards.”Footnote 44 The Commission recognized that “the practice of incorporating detailed technical specifications in Directives ha[d] given rise to long delays because of the unanimity required in Council decision making.”Footnote 45 Going forward, in sectors where barriers to trade are created “justified divergent national regulations concerning the health and safety of citizens and consumer and environmental protection, legislative harmonization will be confined to laying down only the essential requirements, conformity with which will entitle a product to free movement within the Community.”Footnote 46 Instead of setting detailed technical specifications, the Commission would only require conformity to a short list of essential requirements, which would then form the basis of new directives in key sectors—similar to that of the Low Voltage Directive of 1973—requiring that goods meet certain specifications before entering the EC market. Consumer health and safety, along with the estimated risk posed by products and services, determined which sectors required Commission directives. National-level technical regulations and standards were also replaced by regional ones, elaborated by CEN, CENELEC, or other bodies, thereby relieving the Commission of the generative tasks for which it was comparatively ill equipped.Footnote 47

In addition to the narrowed range of essential requirements to which firms bringing goods to the European market were required to adhere, the New Approach also established a new system for the harmonization of voluntary standards. CEN, CENELEC, and ETSI, and not public authorities, became responsible for developing regional standards. The working groups of these standards bodies included “technical experts” from a wide range of stakeholders, including business, which helped to ensure the wide acceptance of the standards they developed.Footnote 48 The Commission resolved to align its legislative aims in “reference to standards,” by “combining the total harmonization of the objectives at issue (safety, etc.) with a flexible approach of the means (standardization).”Footnote 49 As was the case with the principle of mutual recognition, national public authorities were asked to recognize that all products in accordance with harmonized standards presume to conform to the essential requirements defined by EC legislation.

Just months after the Commission's 1985 white paper had initiated the New Approach, EC member states agreed to the first major institutional reform of the Community since the founding Treaty of Rome, signed in 1957. The text of this Single European Act (SEA) described a Europe “at a crossroads”: “we either go ahead—with resolution and determination—or we drop back into mediocrity. We can now either resolve to complete the integration of the economies of Europe; or, through lack of political will to face the immense problems involved, we can simply allow Europe to develop into no more than a free trade area,” like (although it was not explicitly named) the EFTA.Footnote 50 This first amendment to the Treaty of Rome, ratified in February 1986, was designed to facilitate the completion of an internal market in each of three “pillars”—the removal of physical, technical, and fiscal barriers—across nearly three hundred agenda items. The SEA allowed the Council to act “by a qualified majority on a proposal from the Commission, in cooperation with the European Parliament and after consulting the Economic and Social Committee” to adopt, “by means of directives, minimum requirements for gradual implementation, having regard to the conditions and technical rules obtaining in each of the Member States.”Footnote 51 Such changes to the previous methods of unanimity and direct legislation were essential if the EC was to have any hope of completing its internal market by the aggressive “steeplechase” of a deadline on December 31, 1992, inspired, at least in part, by the urgings of those like Philips CEO Wisse Dekker and his even more ambitious “Europe 1990” plan.Footnote 52

Perhaps the strongest articulation of the position of business on the matter came from the European Roundtable of Industrialists (ERT), a group of business leaders who supported market integration in general and the development of common standards in particular.Footnote 53 In June 1985, the ERT, which met biannually with the Commission, issued a memorandum titled “Foundations for the Future of European Industry.” In order to stimulate the technical harmonization and cooperation needed for European firms to rise to the challenge of foreign rivals on scale, price, and productivity, they argued, the EC needed to develop “common European technical standards.”Footnote 54 Claims that the ERT “set the agenda” for the Commission's subsequent relaunching of the integration process may overstate the contribution of business, but a close reading of the ERT position papers and Commission documents from the early 1980s verifies the synergy between industry and the Commission on the need for a true internal market in light of global competition.Footnote 55

The ERT's position on regional standards diverged from those of the Commission, however, in the proposed scope of application: standards should be “EEC-inspired,” but these “new specific policies aiming at European industrial and technological cooperation” ought to be open to non-EEC Europeans and “must be framed to allow for flexibility in developing Europe's links with the rest of the world.”Footnote 56 While the Commission remained focused on the potential of standards to remove trade barriers between EC member states and achieve an insular internal market as a defense against globalization, business leaders on the ERT saw them as a way of reinforcing Europe's global trade connections. Not only did the New Approach establish a single set of requirements for goods in the markets across the EC and EFTA to the great advantage of firms from both inside and outside Europe, but the prospect of harmonizing European standards with those from other parts of the globe promised global economies of scale.Footnote 57

Problems with the New Approach and Introducing a Mark of Conformity

In sharp contrast to the inefficiencies and incrementalism of the Commission's earlier strategies, the New Approach and the SEA synergized the policy and legal regimes working to eliminate technical barriers. Speed was the driving motivation behind the impetus to streamline the regional process of standardization, especially because the Commission aimed to double the usual rate of progress toward setting international standards at the ISO and to produce exponentially more specifications in just seven years than CEN had in its two and a half decades. In addition to making haste, the introduction of qualified majority voting and other democratic instruments through Article 100-A of the SEA agreement also lent credibility to the process of harmonization in Europe. Shortly after the SEA was ratified, the EFTA resolved to incorporate the Commission's latest initiatives into its own convention, obligating its members to adhere to the regulations of Directive 83/189/EEC and paving the way for the synchronous development of common standards, conformity assessment, and certification across countries in the region, regardless of EEC membership.Footnote 58 On December 19, 1989, the EFTA agreed further to exchange information and reciprocity in detailed decisions with the EC, tightening the bond between the two groups, at least as far as standards were concerned.Footnote 59

What the New Approach delivered in expediency and credibility, it lacked in strong enforcement. Its “gravest omission” was “that it required certification “without offering any concrete proposal or initiative to deal with it at the European level.”Footnote 60 The EC had long promised the formalization of certification to regional standards, beginning with the “General Programme” proposed by the First Council Directive of 1968 and the Colonna Report on Industrial Policy in 1970.Footnote 61 It had discussed certification with the Parliament in 1980, prompting Vincent Ansquer, member of the European Parliament from France, to ask in a session the following year when, exactly, the Council intended to introduce a special “EEC Mark,” named for the European Economic Community (EEC).Footnote 62 There was some talk about the possibility of making the CENELEC Certification Agreement of 1984 more widespread to homogenize certification across other sectors.

Furthermore, the New Approach failed to address the heterogeneity of national systems for conformity assessment. When the European Council delivered its Resolution on the New Approach on May 7, 1985, it clearly stated that the “approach will have to be accompanied by a policy on the assessment of conformity.”Footnote 63 Section 8 of the Commission's text had addressed the means of attestation of conformity, including certificates and marks of conformity, results of tests, and manufacturers’ declarations. But instead of developing a comprehensive system, it relied on “specific directives to determine the best means of attestation for the specific requirements of their scope.”Footnote 64 The Commission's first major directive following the New Approach—the 1987 directive regarding simple pressure vessels—implemented a single Community mark, called the “EC mark” in some English language documents.Footnote 65 This mark, “consisting of the symbol ‘CE,’ the last two digits of the year in which the mark was affixed, and the distinguishing number . . . of the approved inspection body,” was be used to indicate a product's compliance with the essential requirements set forward by the Commission (see Figure 1).Footnote 66 Subsequent directives on toys and construction products applied the use of the mark to indicate compliance to the essential requirements established for their respective product categories as well. Still, these directives, focused narrowly on specifications for particular products, offered no remedies for the patchwork of national systems for testing and certification.Footnote 67

Figure 1. The “EC mark” in the 1987 Directive on Simple Pressure Vessels. (Source: European Council Directive 87/404/EEC on Pressure Vessels, Art. 16.)

Industry responses to the New Approach and mark were mixed. Some firms, especially large companies with the resources the conformity assessment and certification process required, welcomed what they saw as a “market passport” for their goods.Footnote 68 Similar to indications of geographic origin (IGOs) and trademarks, the mark promised a means of securing “reputation and market share,” a way to differentiate products and convince consumers of their quality in an increasingly crowded global market.Footnote 69 As a result, compliant companies typically wanted to shore up their investment in the mark by articulating a middling position in their discussions with policymakers: they wanted the mark to remain in use as a way to differentiate their products but were wary of the requirements being either too stringent so as to constrain their market advantage or too lax so as to increase competition. Other companies, often smaller and medium-sized firms, were anxious about the high costs of implementation. For businesses without the capital required to submit prototypes for testing and make production changes before entering the market, a mark of conformity presented a major obstacle.

As a market symbol, the mark promised to indicate to consumers and regulators alike which goods had met the essential requirements. Yet as a policy instrument, it lacked concrete procedures for assessing conformity beyond a disparate network of national testing centers. Without a coherent certification scheme, the New Approach and its corresponding new certification mark were, in large part, rendered toothless. That the lines of text on conformity assessment and certification in the white paper of 1985 were added as an afterthought during the Council meeting demonstrates the extent to which the EC had neglected these central elements of the process.Footnote 70 Alongside the text of a Commission note on the proposal to create a European Center for Control and Certification to solve these problems, someone scrawled “bonne idée ou pas?”—that is, “Good idea, or not?”—summing up the general ambivalence and/or uncertainty about how to proceed with assessing and certifying conformity.Footnote 71

A Global Approach to Testing and Certification

As the Commission worked on the numerous agenda items required to complete the Single Market by 1992, it recognized the need for a more flexible policy instrument and clearer protocols for conformity assessment to remove NTBs to trade between member states. Following a symposium on testing and certification held in Brussels in June 1988, which was well attended by industry representatives, and in light of questions from other EC institutions about how, exactly, “the concept of the ‘EC Mark’ should be understood,” the Commission submitted its proposal for a Council decision concerning the “Global Approach to Conformity Assessment and Certification.”Footnote 72 This proposal was predicated on findings from Commission reports that revealed the cracks in the EC's conformity assessment process and the urgent need for reform if the internal market was going to be completed by the 1992 deadline. It attempted “to bring together all the different elements [of conformity assessment, quality systems, certification, and accreditation] which, when carefully and properly assembled, will give the Community as a whole a comprehensive quality policy which is an indispensable part of any industrial policy and fundamental to the very concept of an Internal Market.”Footnote 73

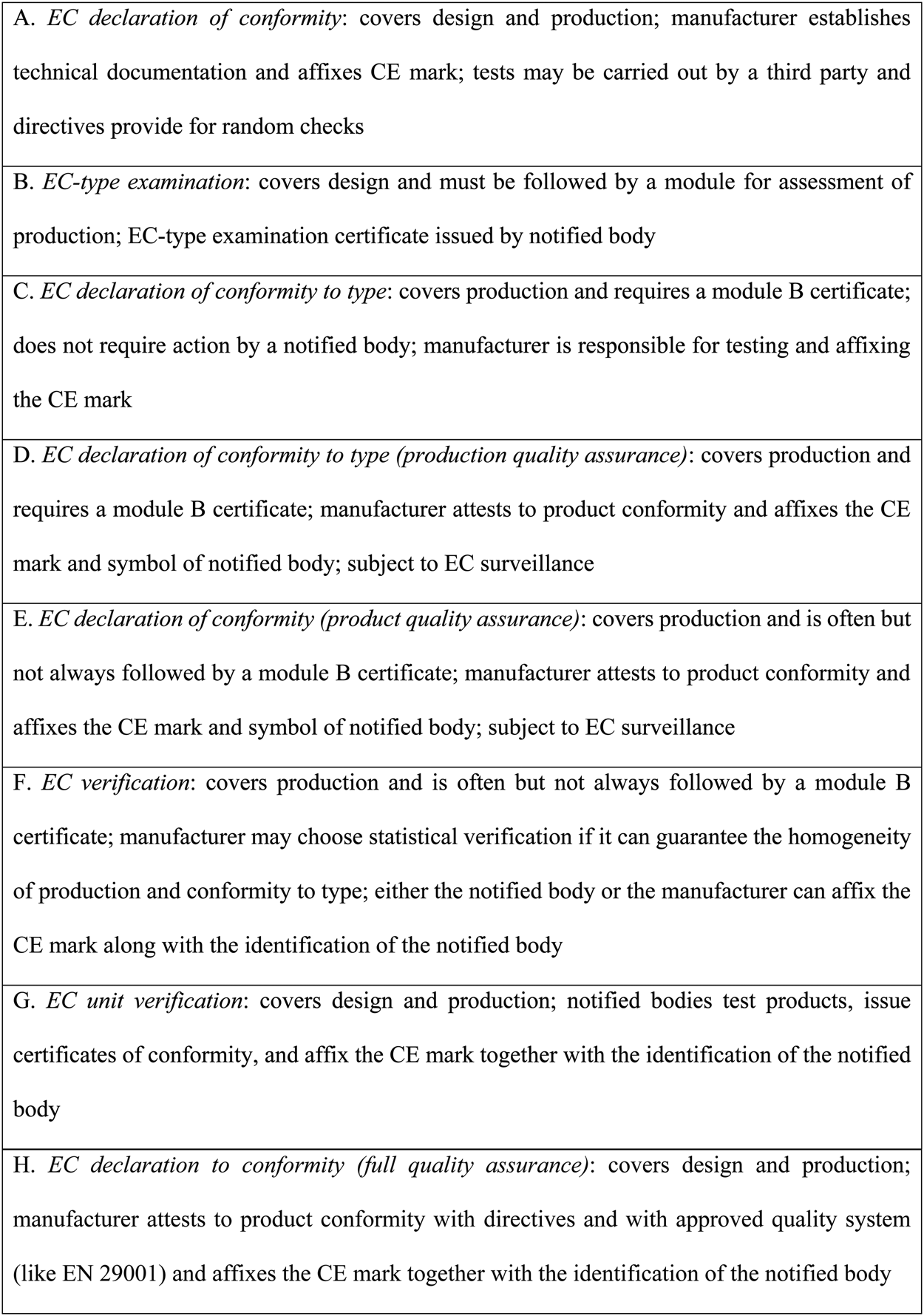

The Global Approach consisted of two core elements: “The Proposal for a Council Decision concerning the Modules for the Various Phases of the Conformity Assessment Procedures Intended to Be Used in the Technical Harmonization Directives”; and the accompanying “Communication on a Global Approach to Certification.” The first established an eight-part “modular system,” outlined in Figure 2, which “subdivided conformity assessment procedures into a number of operations (modules), which differ according to the stage of development of the product, the type of assessment involved, and who carries out the assessment.”Footnote 74 The second element laid out plans for a comprehensive scheme for conformity assessment and certification. Notified bodies, already operating in the apparatus of member state regulatory regimes, would be entrusted with assessing conformity to EC directives as well, and, depending on the module, to affix the revised mark of conformité europeenne—the “CE mark”—to verified products, along with their own identification numbers.

Figure 2. Global Approach modules, 1989. These modules were revised further during the 1990s; for comparison, see the European Commission's 2000 Guide to the Implementation of Directives Based on New Approach and Global Approach. (Source: European Commission, “Global Approach,” chap. 4, sec. 2: “New Legislative Techniques for Conformity Assessment,” 21.)

At the behest of Gerard Caudron, the rapporteur assigned by the European Parliament's Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs and Industrial Policy (CEMAIP) to coordinate the Parliament's response to the Council's request to deliver an opinion on the Global Approach, the Commission agreed to delay the submission of the resolution to the Council until the Parliament had sufficient time to consider this “very important matter.”Footnote 75 Parliamentary deliberation required public feedback on the functioning of the existing system and possible suggestions for reform. In this case, the “public” concerned with conformity assessment and certification was comprised not of individual citizens but of the firms operating within the European market. On December 22, 1989, Caudron circulated a solicitation of industry feedback on the proposal for a Global Approach to fifteen Europe-based organizations, many of them business interest associations (BIAs), asking the following:Footnote 76

1. Is the proposal for a Council decision setting out the permitted modules for future directives necessary at this stage?

2. Are the modules adequate in their present form? If not, do any of them need to be modified, or do they need to be supplemented by further modules?

3. Do you have any other suggestions for improving the Commission text?

4. Do you support the establishment of a European organization for testing and certification?

5. Do you have any comments on the criteria for the use of the CE mark?Footnote 77

The repository of position papers submitted back to the Parliament—from groups like the Committee of Common Market Automobile Constructors (CCMC), the Union des industries de la communauté européenne (UNICE), and the EC Committee of the American Chamber of Commerce (AMCHAM)—attests to the high priority that industry placed on reforming conformity assessment and certification in the EC.

Their sectoral diversity notwithstanding, the majority of these associations expressed broad support for the proposals contained in the Global Approach but continued frustration with the redundancies of assessing and certifying conformity, plagued by “too many possible methods and undue confusion and legal ambiguity.”Footnote 78 First, industry representatives noted that even the two components of the Global Approach “lacked coordination between them, with the proposal for rationalizing the use of the Community mark varying considerably from one directive to the next.”Footnote 79 Second, the Commission's ad hoc approach to developing its directives meant that many key products fell under the guidelines of more than one directive. Firms producing home cooking appliances, for example, had no idea whether their product should adhere to the directive on simple pressure vessels, machines, appliances burning gaseous fuels, or hot water boilers.

Additionally, as the Italian Confindustria ANIE pointed out, “if a product has to conform to a number of different directives, most notified certification bodies will not be competent to check conformity in all these areas.”Footnote 80 In light of these problems, and echoing the position of Europe's technology business association ORGALIME, ANIE argued that ‘manufacturers responsible for their own products should always affix the CE mark regardless of the method used to verify conformity (first-, second-, or third-party assessment) and that notified bodies should then affix their own stamps of certification alongside the curvature of the CE mark.’Footnote 81 The French Conseil national du patronat français (CNPF), dually representing the position of the CCMC, suggested the harmonization process would benefit from the creation of a consultative body and, since the New Approach had introduced standards into the process, that clarification of the differences between obligatory and voluntary conformity was necessary.Footnote 82

For its part, AMCHAM expressed concern about mechanisms for the accreditation of testing laboratories located in third countries (outside the EC), both because the manufacturing of its members often occurred in third countries and because the new EC certification requirements would likely cause a backlog of work for notified bodies and their laboratories in the EC.Footnote 83 EFTA members shared similar concerns. After quibbling over the nomenclature of “marks” versus “initials,” UNICE, compelled by a unique set of interests relative to the other BIAs consulted, took substantive aim at the certification procedures supporting the affixing of the mark, the testing for which, it argued, was prohibitively expensive for many of its small and medium-sized constituents.Footnote 84 Not surprisingly, many of the BIAs that submitted position papers encouraged the use of international ISO standards by regional standards bodies and the Commission wherever possible. Such convergence with global standards would allow European firms to achieve the scale and scope required to compete.Footnote 85 Overall, the diverse business groups consulted argued that the Global Approach's lack of clarity impeded economic development in the region because companies were unsure of how to confirm their products’ conformity to the essential requirements stipulated by the EC's directives.Footnote 86

The European Parliament made quick work of synthesizing industry feedback and submitted several amendments to the Commission at its May 1990 session, ranging from the insurance of severe penalties for abuse of the new standardization system (Amendment 3) to clarifying the conditions of compliance required for the affixing of the CE mark (Amendment 9).Footnote 87 As rapporteur, Caudron made four sets of general recommendations on “the need to avoid too much bureaucracy in the process of ensuring conformity with essential requirements, the need for certain accompanying measures to be taken, and finally the issue of whether the existing modules should be modified.”Footnote 88 In October 1990, the Commission authored the “Green Paper on the Development of European Standardization: Actions for Faster Technological Integration in Europe,” in which it stressed the need for a common marking system to remedy “the large degree of confusion on the question of marking, underlined by the different regimes existing within CEN/CENELEC circles,” and described a common mark of conformity as “a logical consequence of self-standing European standards,” which would save manufacturers time and increase consumer confidence in the entire European market.Footnote 89 By December, the Commission had drafted the “Re-examined Proposal for a Council Decision,” in which it adopted three amendments into its revised proposal for a Council decision on modules and subcontracting.

The Parliament's recommendations on amending the application of the CE mark were not accepted, however. “The Council took the view that, pending examination and adoption of a directive on the CE Mark, it would be inappropriate to prejudge the details thereof, and it opted therefore for the simple deletion of the provision of the CE Mark, confining itself to a straight factual reference to the future CE Mark in modules.”Footnote 90 The Parliament wrote back, seemingly dismayed by the Council's dropping of Amendments 9 and 11 on the use of the mark, asking for the Commission to submit its proposed directive on certification and marks of conformity as rapidly as possible, since it had neglected to do so in its 1990 annual legislative program.Footnote 91

CE Marking for the EU and EEA

Finally, in May 1991, the Commission proposed a Council Regulation on the CE mark.Footnote 92 The Economic and Social Committee and the parliamentary CEMAIP were again asked to consult on the proposal.Footnote 93 The subsequent drafting of the Maastricht Treaty on the European Union in December 1991 and its signing in February 1992 offered a boost of momentum to the Commission to finalize this previously fraught element of the harmonization process.Footnote 94 Amid the frenzied rush to complete the last of the agenda items to complete the Single European Market by the December 1992 deadline, the Commission penned its final “Amendment to the Proposal for a Council Regulation (EEC) concerning the affixing and use of the CE mark of conformity on industrial products.”Footnote 95 This amendment articulated a much more flexible approach to the CE mark, recognizing the full legal validity of marked products irrespective of the date on which the product entered the market, rendering optional the identification of the notified body and allowing a ten-year grace period for manufacturers legally using a mark resembling the CE mark to attain full compliance. As the business associations had requested, the Commission also warned that deliberate improper affixing of the mark would have serious consequences, including the withdrawal of that product from the market.Footnote 96 The flurry of parliamentary documents on the mark and its reform from the sessions of 1991 to 1993 highlight the challenge of arriving at an implementation of the mark that met the wide-ranging needs and interests of industry, consumers, and policymakers intent on completing the internal market.

In its final form, even though the EC Council declared that “the Community endeavors to promote international trade in products subject to regulation,” the Global Approach on modules for conformity assessment and certification did not allow notified bodies to subcontract work to bodies located in third countries, nor those for direct recognition of third-country-body assessment and certification aligned with Community legislation.Footnote 97 Because the EC had no way to guarantee that third-country bodies would prioritize the health and safety of European consumers and because third countries were unwilling to promise reciprocal access to European enterprises in third markets, the EC rejected the largest multilateral scope of the Global Approach's application.Footnote 98 As the EU evolved its position further in the 1990s, it agreed to favor the signatory countries of the GATT code on technical barriers to trade. But EFTA member states, already committed to the New Approach and corresponding directives, were exempt from these exclusions and were treated as members of the internal market already, at least where standards, conformity assessment, and certification were concerned.

Just months after the CE mark amendment was accepted, with only a relative few of the original agenda items remaining on the Commission's 1992 Program docket, the Single European Market was declared complete, paving a new road ahead for tEuropean Union, its continued objective of economic and monetary integration, and its external trade and economic coordination agreements. One of the most important economic agreements made by the new EU was with the EFTA. In March 1994, these two organizations, despite the differences in their member states’ desired degrees of integration, signed an agreement creating the European Economic Area.Footnote 99 Their collective aim was not “ever closer union,” as had been the case with the formation of the EEC in the Treaty of Rome.Footnote 100 Instead, “determined to contribute, on the basis of market economy, to world-wide trade liberalization and cooperation, in particular in accordance with the provisions of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade and the Convention on the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development,” the EC and EFTA agreed to form an association “to promote a continuous and balanced strengthening of trade and economic relations between the Contracting Parties with equal conditions of competition, and the respect of the same rules, with a view to creating a homogeneous European Economic Area, hereinafter referred to as the EEA.”Footnote 101 A central component of this agreement was the mutual commitment to the system of conformity assessment and certification developed by the New and Global Approaches, to which the 1993 reform directive gave the name “CE Marking.”Footnote 102 Although they were not members of the EC or EU, EFTA countries and their businesses overwhelmingly embraced the Commission's consolidated CE marking system of directives, essential requirements, conformity assessment, and certification as a means of accessing the large Single Market and all of its attendant advantages.

Conclusion

The history of CE marking highlights the centrality of standardization, conformity assessment, and certification to market integration, not just in the European Community and European Union but throughout the European region. The standardization necessary to complete the Single European Market required the EC's cooperation with several other intergovernmental organizations, including regional standards bodies like CEN and CENELEC, global frameworks like the GATT and global organizations like ISO, and other regional trade groups like the EFTA. Even if the European Commission's New Approach was developed as a defensive way to shore up the EC and its market against the challenges of globalization, it also paved the way for closer cooperation with the European region beyond the EC. From 1994 on, CE marking defined not only the EU's Single Market but the wider transcontinental market, from Britain to the Peloponnese, Scandinavia to Sicily. That more than half of the original EFTA countries had become EU members by the mid-1990s provides insight into their willingness to accept the Commission's standards regime even before accession and highlights the degree of market integration that had already occurred before the EEA agreement was signed.

In addition to expanding the narrative of European market integration, the history of CE marking also sheds light on the relationship between business and regulation in Europe during this crucial period of the 1980s and 1990s. Correspondence between business associations and the institutions of the EC and EU reveals that firms largely supported the New and Global Approaches out of a desire for access to a large internal market. What is more, the modularity and flexibility of the Global Approach made business conformity much more straightforward than the cumbersome “old approach” and incentivized firms to use voluntary standards and embrace the new conformity and certification processes of CE marking. Business groups also provided feedback crucial for developing a more cohesive and less restrictive assessment and certification process. When consulted about the Global Approach, big businesses—especially multinational corporations with operations inside and outside of Europe—wanted to ensure that European standardization would facilitate economies of scale beyond the EC and asked the Communityto align its directives as much as possible with standards set by the ISO and other international bodies. Companies with fewer resources and more restricted access to European testing and certification sites appealed for a less stringent testing system, lest CE marking become a barrier to market entry. Pared-down essential requirements and voluntary standards reduced the burden of company compliance, and the clarification of modules and greater flexibility on conformity assessment and certification enabled even smaller enterprises to bring their goods to the European market. Beyond compliance with the essential requirements, increasing use of the CE mark by businesses indicated the perceived advantages of the mark as a form of “European branding” and product differentiation on both European and global markets.

Finally, the history of CE marking poses several new research questions, especially relating to the EFTA. Building on the foundation of this article, scholars could ask, What were the positions of individual EFTA member states on the introduction of CE marking? Do EFTA archives reveal further participation by business in—or perhaps differing perspectives on—the integration of European markets through standardization? Additional research is needed to mine historical documents of the EFTA, the archives of national standards bodies, and the personal papers of leading figures involved in the development of CE marking for answers to these and other questions. More scholarship on the subject using those materials would continue to expand histories of regional market integration and further explain the complex ways businesses related to and, in turn, shaped the European business environment.