Introduction

Was W. E. B. Du Bois a quant? At first blush, his late-twentieth- and early-twenty-first-century influence on sociology has primarily been seen in qualitative research and new theorizing in the sociology of race (Itzigsohn and Brown, Reference Itzigsohn and Brown2015), urban sociology (Loughran Reference Loughran2015), and the sociology of education (Conwell Reference Conwell2016), among other domains of knowledge production. Du Bois’s staggering body of writing—which traverses nearly seventy years, seventeen books, 100 published articles, and 100,000 archived documents, and which includes writings in sociology, fiction, autobiography, and other genres—makes him a polyvalent historical intellectual from whom a range of epistemological and methodological viewpoints can be derived (Jansen Reference Jansen2007; Schwartz Reference Schwartz2000). One of the central political-epistemological questions for a twenty-first-century Du Boisian sociology, therefore, is how to translate varied ideas—some now well over a century old—into a contemporary research agenda (Rabaka Reference Rabaka2010). We argue that, as part of this effort, it is time for Du Boisian scholars to make a methodological turn. In this study, we explicitly take a partial view (Haraway Reference Haraway1988) that excavates Du Bois’s approach to quantitative inquiry.

Existing scholarship on Du Bois does feature some attention to methodology—that is, his epistemological bases for the use of a particular method or set of methods (Harding Reference Harding1991; Stanfield Reference Stanfield2016). Scholars agree that Du Bois’s overall social-scientific approach was one of mixed-methods triangulation, often combining quantitative methods with interviews and field observation (Clair Reference Clair2021; Itzigsohn and Brown, Reference Itzigsohn and Brown2020; Morris Reference Morris2015; Rabaka Reference Rabaka2010; Williams Reference Williams2006). Du Bois used these empirical methods to accumulate knowledge about Black people from the group’s perspective, emphasizing individual agency from a subaltern positionality and pushing back against the speculative and racist theorizing about Blacks common to social science at the turn of the twentieth century (Bobo Reference Bobo2015; Hunter Reference Hunter2013; Morris Reference Morris2023). Speaking to Du Bois’s qualitative methods, Karida Brown (Reference Brown2018, see research appendix) provides a thoughtful analysis of Du Bois’s qualitative methodology and links those ideas to contemporary research practices.

With respect to our topic of Du Bois’s quantitative work, research on the potentially anti-racist use of quantitative methods has at times drawn on Du Bois’s use of quantitative methods in The Philadelphia Negro (Reference Du Bois2007b [1899]) as an exemplar. Tukufu Zuberi (Reference Zuberi2001) notes that Du Bois “used racial statistics to support racial justice” and leveraged descriptive statistical analysis to bring forward a structural understanding of racism’s impact on Blacks’ life chances (p. 92; see also Bobo Reference Bobo2000, Reference Bobo2015; Zuberi and Bonilla-Silva, Reference Zuberi and Bonilla-Silva2008). Our further explication of Du Bois’s quantitative methodology builds upon these prior discussions and connects Du Bois’s use of quantitative methods in the seminal The Philadelphia Negro (Reference Du Bois2007b [1899]) to some of his other early work.

The remainder of the paper unfolds in three parts. First, we offer a constructively critical appraisal of what we term the New Du Boisian Sociology, a body of scholarship that, since the 1990s, has clarified, elevated, and synthesized Du Bois’s sociological contributions and become increasingly “organized and self-aware” in the past decade (Griswold Reference Griswold1987, p. 4). We argue that greater focus on Du Bois’s empirical methodologies is an important and strategic next step for the field. Second, we provide a detailed analysis of how and why Du Bois developed an inductive (i.e., bottom-up), theoretically generative approach to his social science research, including his use of quantitative data and methods. Here we draw on writings about Du Bois’s formative educational experiences and his sociological research goals, including his first-person discussions of these topics in his two autobiographies and other works (Du Bois Reference Du Bois2000 [1905], Reference Du Bois2007a [1940], Reference Du Bois2014 [1968]). Third, we examine Du Bois’s use of statistical data and methods in “The Negroes of Farmville, Virginia” (Du Bois Reference Du Bois1898a), The Philadelphia Negro (Du Bois Reference Du Bois2007b [1899]) and The Negro Artisan (Du Bois ed. Reference Du Bois1902), framing the discussion with a review of “The Study of the Negro Problems” (Du Bois Reference Du Bois1898b), one of his clearest methodological statements. Prior work on Du Bois’s early scholarship has also discussed the Farmville study, The Philadelphia Negro, and select Atlanta studies as illustrative of Du Bois’s research approach and search for scientific “Truth” during his early sociological period; at the time, his stated goal was to understand general social laws via systematic data collection on and analysis of Black life, followed by generalization from the data (Williams Reference Williams2006, p. 368). Here we dig more deeply into Du Bois’s use of quantitative methods in these early works.

Specifically, we identify and break down the key elements of what we term Du Boisian quantification. This framework encompasses both Du Bois’s uses of quantitative data (multiple sources, levels of institutional and geographic aggregation, and generations, with attention to missing and fallible data) and his most common strategies for quantitative analysis (description, within- and between-race comparison, and intersections of race with other factors). We moderate a thematic conversation between Farmville, The Philadelphia Negro, and The Negro Artisan, illustrating each theme with selected examples drawn from our focal studies. For the interested practitioner, we also link Du Bois’s quantitative approach to roughly equivalent current research practices; some of these, like exploratory (i.e., inductive quantitative) data analysis, are underrepresented in contemporary sociology.

Our conclusion discusses potential barriers to greater uptake of a Du Boisian quantitative approach in contemporary sociology, arguing that these barriers can and should be overcome. We also enter Du Bois, as historical precedent, into broader debates regarding quantification’s productive role, if any, in social science research on race/racism and other axes of structural inequality. We foreground the tension between, on the one hand, the recent “QuantCrit” movement (Garcia and López, Reference Garcia, López and Vélez2018; López et al., Reference López, Erwin, Binder and Chavez2018)—advocating for the critical quantitative study of these social dynamics—and, on the other, the critique that, when it comes to these topics, “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house” (Bowleg Reference Bowleg2008, Reference Bowleg2021 quoting Lorde Reference Lorde1984), meaning researchers should favor qualitative or qualitative-led mixed methods approaches.

Du Bois as Scholar and Symbol: Sociology’s Collective Memory and the Politics of Knowledge

The advancement of an explicitly Du Boisian perspective in contemporary sociology is at once an intellectual project and a social movement, an exercise in both method and memorialization. As such, our effort to excavate Du Bois’s quantitative methodology must also be situated within the politics of knowledge that surround the Du Boisian moment—specifically, how Du Bois the sociologist and Du Bois the symbol create opportunities as well as constraints for initiating a methodological turn within the ongoing reclamation and theory-building work that we term the New Du Boisian Sociology (Hunter Reference Hunter2013; Itzigsohn and Brown, Reference Itzigsohn and Brown2020; Morris Reference Morris2015; Rabaka Reference Rabaka2010). At stake for many contemporary Du Boisians is the inclusion of Du Bois into what “‘the Keepers of the Canon’ regard as the core works, concepts, theories, and figures of American sociology” (Bobo Reference Bobo2015, p. 464; see also Burawoy Reference Burawoy2022; Itzigsohn and Brown, Reference Itzigsohn and Brown2020; Young Reference Young2015). Canons are socially constructed products of ongoing debates about the applicability and empirical validity of historical theories and methodologies (Go Reference Go2020; Matlon Reference Matlon2022); they are reputational achievements for the canonized scholars (Fine Reference Fine2001). But reputations change, and even the canonized are not guaranteed ongoing relevance to sociological investigations, as not all old ideas are interpreted equally by later generations (Halbwachs Reference Halbwachs1992 [1941]; Parker Reference Parker and Vallet2020). For example, some argue that Durkheim might have been wrong about the causes of suicide, but maybe he was right about the dynamics of social organization (Pescosolido and Georgianna, Reference Pescosolido and Georgianna1989; Kushner and Sterk, Reference Kushner and Sterk2005).

Despite his pathbreaking sociological achievements and decades-long stature as a foremost public intellectual, Du Bois’s writings and ideas were far from the sociological mainstream until the 1990s, and many sociologists simply never encountered his work (Anderson Reference Anderson1996; Itzigsohn and Brown, Reference Itzigsohn and Brown2020; Morris Reference Morris2015; Parker Reference Parker1997; Rabaka Reference Rabaka2010; for an exception, see Green and Driver eds., Reference Green and Driver1978). Even today, sympathetic scholars struggle to meaningfully incorporate Du Bois into syllabi and into their thinking (Flower Reference Flower1994). As Julian Go (Reference Go2016) writes, “[A]t most, mainstream social theorists pick out Du Bois’s concepts of ‘double consciousness’ or the ‘veil.’ But less attention, if any, is paid to his critique of conventional sociology [or] his analysis of racialized systems as constitutive of modern society and of knowledge” (p. 13). The central epistemic and social movement problem facing contemporary Du Boisians, therefore, is how to activate the historical Du Bois not merely as a tokenized sociological figure but as an intellectual force in the present day.

A perverse saving grace for Du Bois’s work is that his focus on the global social structures of race and racism—enshrined in his enduring quote about the “problem of the twentieth century” (Du Bois Reference Du Bois1994 [1903], p. 9)—has proved more than prophetic. Rival scholars like Robert Park might have intentionally marginalized him (Morris Reference Morris2015), and mainstream sociologists might have ignored him, but the persistence of racism has ensured that Du Bois’s ideas are far from obsolete, even as the social structures of race and racism change (Alston Reference Alston2018; Barnes Reference Barnes2021; Binkovitz Reference Binkovitz2022; Clair Reference Clair2021; Dantzler Reference Dantzler2021). If anything, the development of kindred bodies of knowledge like intersectionality and critical race theory, coupled with the potential diminishment of sociology’s “colorblind” (Bonilla-Silva Reference Bonilla-Silva2003) worldview, have only served to increase the clear importance of Du Bois’s work and the need to reconsider not only “paths not taken” (Morris Reference Morris and Calhoun2007) but paths forward.

We argue that those paths forward are ambiguous at present. Due in part to what we consider a (necessary) ‘strategic sequencing’ in the New Du Boisian Sociology, most work to date has sought to uncover Du Bois’s hidden contributions to sociological knowledge, providing key intellectual scaffolding to support new investigations (Itzigsohn and Brown, Reference Itzigsohn and Brown2020; Morris Reference Morris2015). Without these contributions to guide and organize new work, there could be no meaningful investigation of Du Bois’s methodology or new theorizing on race that meaningfully builds on Du Bois’s ideas. At the same time, we join Reiland Rabaka’s (Reference Rabaka2010) call for “contemporary Du Bois scholars, especially critical sociologists, to move beyond their meditations on his sociological negation and make concrete contributions, not simply to sociology but to the radical democratic transformation of our respective societies and the wider world” (p. 5). One crucial way for such work to proceed is by charting a methodological turn—that is, encouraging work that is not only spiritually inspired by Du Bois but work that seeks to do sociological research in the manner that he did.

Getting specific about Du Bois’s quantitative data collection practices and analytic choices—as we do here in hopes that they will be better understood by and instructive to contemporary sociologists—brings with it the necessity of acknowledging other practices in which he could have engaged; other choices he could have made; and ways his methodological practices and decisions simultaneously enhanced and limited the impact of his science, historically and at present. The latter includes discussing how his specific manner of conducting quantitative research generates both opportunities and challenges for contemporary (re)adoption. We argue that more work of this type is essential if we seek to accord Du Bois and Du Boisian sociologists the same kinds of epistemic trials (Duneier Reference Duneier2011)—and by extension, the same respect—that has for long been part of the intellectual legacies of canonized scholars like Marx, Weber, and Durkheim (e.g., Barrow Reference Barrow1993; Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Hazelrigg and Pope1975; see also Hunter Reference Hunter2016 on “intellectual reparations”).

The New Du Boisian Sociology does feature some attention to Du Bois’s methodology. As we noted earlier, mentioning that Du Bois utilized a mixed-methods triangulation approach is a common practice in this literature. Recently, in The Sociology of W. E. B. Du Bois: Racialized Modernity and the Global Color Line, José Itzigsohn and Karida Brown (Reference Itzigsohn and Brown2020) write, “[W]e are not being prescriptive as to which methods one must use in order to be regarded as a Du Boisian sociologist” (p. 200). They recommend that prospective Du Boisian scholars receive training in contemporary advanced quantitative methods and are clear that there are ways scholars can use both quantitative and qualitative methods that are more or less consistent with Du Bois’s overall social-scientific approach, which they describe as “contextual, historical, and relational” (p. 200). Building on this prior work, we argue that more depth and specificity is possible, especially regarding Du Bois’s quantitative methodology, as there is a sharp divergence between his logic and methods of quantitative inquiry and those that predominate today.

Quantitative Methodology in Du Bois’s Intellectual Biography

Three aspects of Du Bois’s intellectual biography inform our study of his quantitative methodology. First, although a hallmark of Du Bois’s written output is that it blurs binaries such as quantitative/qualitative and social science/literature, Du Bois produced a large body of insightful and still widely read work that skews heavily qualitative, in the forms of literature, poetry, essays, and autobiography. Some of these works were the places where contemporary social scientists (present authors included) first encountered Du Bois as undergraduate or graduate students. This portion of Du Bois’s oeuvre also birthed many of the ideas that contemporary social scientists most closely associate with him, such as double consciousness, from his semi-autobiographical essay “Of Our Spiritual Strivings” in The Souls of Black Folk (Reference Du Bois1994 [1903]).

Even Du Bois’s more literary and autobiographical writings, however, reveal quantification’s centrality to his thinking. Literary critic Sarah Wilson (Reference Wilson2015) argues that Du Bois used quantification and numbering (impersonal and interchangeable) as symbolic literary devices to assert a notion of Black personhood equal to that of Whites and having the same claim to be members of the nation. As an example, Wilson (Reference Wilson2015) points, in fact, to how Du Bois’s explanation of double consciousness is remarkably numerical: “One ever feels his two-ness, – an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder” (Du Bois Reference Du Bois1994 [1903], p. 2).

Second, Du Bois’s logic of social-scientific inquiry was decidedly inductive (bottom-up and theory-building), instead of deductive (top-down and theory-testing; see Bobo Reference Bobo2014; Du Bois Reference Du Bois2007 [1940], Reference Du Bois2014 [1968]; Itzigsohn and Brown, Reference Itzigsohn and Brown2020; Lewis Reference Lewis1993; Morris Reference Morris2015, Reference Morris2023; Williams Reference Williams2006). The essay “Sociology Hesitant”—in which Du Bois offers his definition of and vision for Sociology as the scientific study of the interplay of Law (social structure) and Chance (individual will and agency)—exemplifies. Du Bois also argued in the essay that the discipline inhered the possibility of taking “the Deeds of Men [sic] as objects of scientific study and induction” (Reference Du Bois2000 [1905], p. 38). Elaborating on this theme in this first volume of his two-part autobiography of Du Bois, David Levering Lewis (Reference Lewis1993) notes that, in contrast to Auguste Comte, Karl Marx, and Herbert Spencer, Du Bois’s pathbreaking empiricism inaugurated a social-scientific era in which “the watchword of the discipline was becoming investigation, followed by induction—facts before theory” (p. 202, italics in original). Lewis describes The Philadelphia Negro as an exemplar of this inductive approach: as we detail later, the manuscript is weighted heavily towards the presentation and analysis of tables and figures based on survey, census, and archival data, with theoretical arguments spliced between a litany of tables and figures.

Du Bois’s inductive social-scientific approach had roots in his cross-Atlantic higher education experiences. This journey began at Fisk University with classics, including philosophy under university president Erastus Cravath, and continued at Harvard, where Du Bois studied philosophy under William James and history under Albert Bushnell Hart; the latter specialized in research methods and was a proponent of historical inquiry that, following the physical sciences, relied on data and inductive reasoning and was “akin to a quantitative science” (Edwards Reference Edwards2006, p. 400; see also Du Bois Reference Du Bois2007a [1940]; Lewis Reference Lewis1993). Du Bois then studied at Berlin during the “Battle of Methods,” a period of fierce debate within the European academy about the relative merits of deductive versus inductive approaches to economic research (Boston Reference Boston1991; Edwards Reference Edwards2006; Lewis Reference Lewis1993; Wortham Reference Wortham2009). He studied under Gustav von Schmoller and other prominent defenders of an inductive research approach. Schmoller and colleagues’ preferred methodology was heavily data-driven, descriptive, interdisciplinary, historically and contextually informed, little concerned with theoretical abstraction, and guided by ethical concerns (Boston Reference Boston1991; Edwards Reference Edwards2006; Lewis Reference Lewis1993; Wortham Reference Wortham2009). Du Bois completed his graduate studies in History back at Harvard, after running out of scholarship funds that would have enabled him to complete the more prestigious doctorate in Economics at Berlin (Edwards Reference Edwards2006; Lewis Reference Lewis1993).

Du Bois’s data-driven, inductive approach to social-scientific research, including its quantitative varieties, combined these intellectual strands. As Lewis (Reference Lewis1993) summarizes:

Du Bois’s seminar notes quoted Schmoller as saying “My school tries as far as possible to leave the Sollen [should be] for a later stage and study the Geschehen [what is actual] as other sciences have done.” It was another way of saying what James and Hart had said—that in History, large patterns emerge only after much sifting of the particulars (p. 142).

We take seriously Rabaka’s (Reference Rabaka2010) contention that Du Bois scholars should not “incessantly seek to interpret his contributions to sociology as somehow, always and ever, derivative of or consequent to” his studies Harvard and Berlin (p. 39). However, a genuinely sociological perspective on the interplay of Law and Chance in Du Bois’s own intellectual development would hold that it was mutually constituted by, on one hand, his singular vision and determination and, on the other, his educational contexts and opportunities, including his mentors. In this vein, we keep in mind Lewis’s (Reference Lewis1993) arguments that Du Bois’s Harvard years should be seen as part of “the bed of his own contingent and very human success story” (p. 81) and that, at Berlin, “[H]ad he fallen under the tutelage of Georg Simmel, the star of sociology at Berlin, Du Bois’s approach to sociology might have been radically different, [given Simmel’s] subordination of social behavior to comprehensive systems” (p. 143). Indeed, Du Bois (Reference Du Bois2007a [1940], Reference Du Bois2014 [1968]) acknowledges scholars from both Harvard and Berlin in various writings about his life and scientific approach (c.f., Edwards Reference Edwards2006). For example, in his second autobiography Du Bois (Reference Du Bois2014 [1968]) writes of his time at Harvard: “…it was James with his pragmatism and Albert Bushnell Hart with his research method, that turned me back from the lovely but sterile land of philosophic speculation, to the social sciences as the field for gathering and interpreting that body of fact which would apply to my program for the Negro” (p. 93).

Du Bois’s inductive approach was both spurred on by his training and necessitated by his topic. Social science at the turn of the twentieth century was rife with theories of Social Darwinism, placing Blacks at the bottom of essential hierarchies and predicting the race’s extinction. In African American Pioneers of Sociology: A Critical History, Pierre Saint-Arnaud (Reference Saint-Arnaud2009) defines Du Boisian empiricism as resting on twin pillars of historicism and empirical positivism, arguing that it owes to both Schmoller’s influence (data, inductive theorizing, and hopefully social change based on facts) and the then-contemporary ‘scientific’ consensus about race: “Du Bois simply had no theoretical corpus on which to base a contrary position. He had to build a new science from the ground up, a science devoted to the advancement, as opposed to the near-term extinction, of black Americans” (p. 140).

Reliance on inductive reasoning is also key to Saint-Arnaud’s (2003) arguments that Du Bois’s scientific legacy was limited due to his failure to develop systematic theory and that he would have “run into major cognitive difficulties” had he remained a formal sociologist beyond departing Atlanta University in 1914 (p. 156). Some scholars in the New Du Boisian Sociology and other research streams have argued for and explicated systematic theory within Du Bois’s work (Itzigsohn and Brown, Reference Itzigsohn and Brown2020; Morris Reference Morris2015). Alternatively, others have acknowledged Du Bois’s failure to fully realize his research goals, including his theoretical ones, but argued that this was because of resource constraints facing his research program at Atlanta University and Du Bois’s changing philosophy of the relationship between social science and social change, which over time evolved towards more direct engagement (Williams Reference Williams2006). Saint-Arnaud’s critique on these grounds, however, only further demonstrates induction’s centrality to a Du Boisian empirical approach.

Critically, an inductive approach means that, by contemporary quantitative sociology’s standards, Du Bois’s quantitative research reads as upside-down. At current, varying combinations of deductive theory testing and causal inference based on experimental or quasi-experimental methods cohere as a “gold standard” for quantitative research to receive funding and be published in prestigious journals (Sampson Reference Sampson2010). Qualitative scholars have perhaps been most critical of these standards, countering the resulting perceptions that qualitative research is less rigorous than quantitative research. Martin Packer (Reference Packer2011) argues that the impetus towards causal inference and hypothesis testing “has become an oppressive prescription…To force scientists to conduct only hypothesis-testing research is to prevent them from challenging the rules of the game, from questioning or even examining the assumptions in the prevalent scientific paradigm” (p. 37, quoted in Saiani Reference Saiani2018). Less prominent in the qualitative/quantitative debate is the fact that these standards also marginalize descriptive and inductive quantitative research because it does not test existing theories or seek to make causal claims in formally statistical terms. But description and induction define the type of quantitative research that Du Bois had to conduct in an era of Social Darwinist theories and that, we will argue, contemporary researchers who seek to return to a Du Boisian tradition should embrace moving forward, at least in some of their work.

Third, the descriptive quantitative methods that Du Bois relied upon can appear quaint and dated in our present era of great leaps forward in quantitative data sources and collection strategies, statistical computing software, and data visualization techniques. Even Aldon Morris (Reference Morris2015) concedes that the Atlanta University studies could have been stronger methodologically, while also noting that this is often the fate of pioneers who chart a new path without models to follow, as Du Bois did. Concessions about statistical techniques contrast enormously with how scholars laud concepts like double consciousness and “the problem of the Twentieth Century” as unfailingly prescient. Even in the present era, however, Du Bois’s work encourages scholars to use available tools while making a refreshing return to quantitative research that is systematic and rigorous, yet also exploratory, inductive, and descriptive. Such a manner of working both complements and challenges the hypothetico-deductive paradigm’s contemporary dominance in quantitative sociological research.

Quantitative Methodology in Du Bois’s Early Sociological Works

Du Bois’s essential article “The Study of the Negro Problems,” published in The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science in 1898, is one of his clearest methodological statements. It justifies the completist mode of data collection and descriptive quantitative analysis featured in his early work. Writing at a time when, as described above, White conjecture formed the social science consensus on race, Du Bois (Reference Du Bois1898b) pushed for cold, hard data; numbers, he seemed to hold, were irrefutable:

The collection of statistics should be carried on with increased care and thoroughness. It is no credit to a great modern nation that so much well-grounded doubt can be thrown on our present knowledge of the simple matters of number, age, sex and conjugal condition in regard to our Negro population. General statistical investigations should avoid seeking to tabulate more intricate social conditions than the ones indicated. The concrete social status of the Negro can only be ascertained by intensive studies carried on in definitely limited localities, by competent investigators, in accordance with one general plan. […] Such investigations should be extended until they cover the typical group life of Negroes in all sections of the land and should be so repeated from time to time in the same localities and with the same methods, as to be a measure of social development. […] [S]ociological interpretation … should include the arrangement and interpretation of historical and statistical matter in the light of the experience of other nations and other ages (pp. 18-19).

Here we see Du Bois articulating a quantitative methodological philosophy including thorough data collection, sociologically informed analysis of descriptive statistics (see also Bulmer Reference Bulmer, Bulmer, Bales and Sklar1991b; Zuberi Reference Zuberi2001) and comparative and historical interpretation. He also hoped that studies conducted in this vein would be replicated and compared both in locales across the United States and over time, in line with his proposed but uncompleted plan for the Atlanta University studies; these were to repeat in decade cycles, adding up to a century of research (see Wright Reference Wright2016).

Couched within his inductive logic of inquiry, Du Bois’s quantitative approach resonates strongly, although of course not perfectly, with what contemporary scholars refer to as exploratory data analysis (EDA; c.f., Jebb et al., Reference Jebb, Parrigon and Woo2017). EDA is “the statistical embodiment of inductive research”; in contrast to confirmatory (deductive and hypothesis testing) data analysis, EDA is “characterized by an extreme flexibility that is necessary for identifying a range of statistical and substantive phenomena that emerge during empirical research” (Jebb et al., Reference Jebb, Parrigon and Woo2017, p. 266). The term describes a general attitude towards data, not a specific model or set of procedures.

Themes of EDA that resonate strongly with Du Bois’s use of quantitative data and methods include context-specificity (or, in his words, “intensive studies carried on in definitely limited localities”); simple calculations (“simple matters,” “avoid seeking to tabulate more intricate social conditions…”); openness to both regular and unexpected phenomena; and healthy skepticism of quantitative data (Jebb et al., Reference Jebb, Parrigon and Woo2017). Exploratory data analysts are detectives who answer the question ‘[W]hat is going on here?’ by identifying and describing patterns in quantitative data (i.e., phenomenon detection; Jebb et al., Reference Jebb, Parrigon and Woo2017; Tukey Reference Tukey1980). During the period we study, Du Bois used quantitative data and methods to answer this question for Farmville, Virginia (Reference Du Bois1898a); Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (Reference Du Bois2007b [1899]); Atlanta and the State of Georgia (ed. 1902); and, often while doing so, the whole United States, sometimes in both historical and international comparison—or, as he put it, “in the light of the experience of other nations and other ages.”

Data: Multiple Sources, Levels of Geographic and Institutional Aggregation, and Generations

Du Bois’s early studies blended primary and secondary data sources, spanning levels of aggregation from local to state to national to cross-national. His quantitative data also often included multiple historical time periods and generations. The former reminds of his training in history, while the latter showcases his enduring interest in Black children and young adults, particularly their education, as key to the race’s prospects (c.f., Conwell Reference Conwell2016). Du Bois’s approach to quantitative data also included consistent attention to missing and fallible data, due to issues such as poorly kept or missing records, or survey respondents misremembering information or giving false responses.

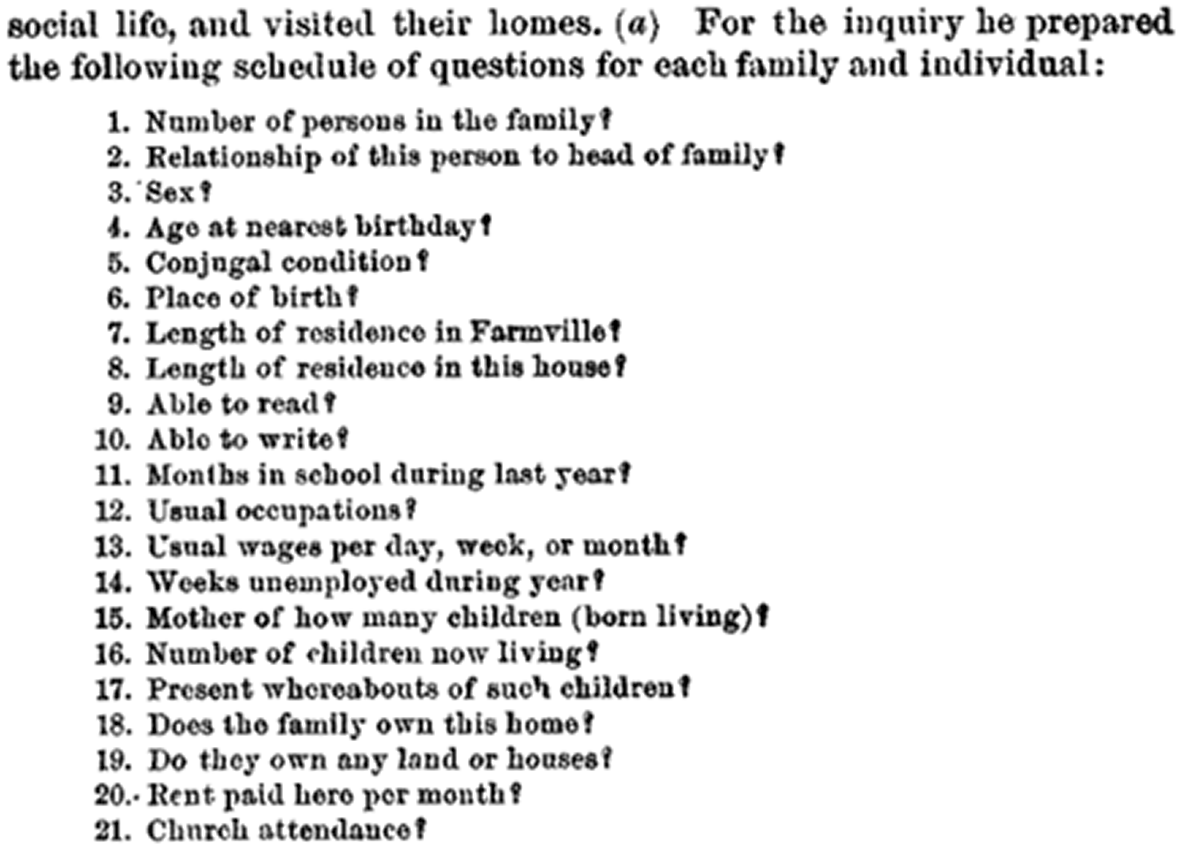

“The Negroes of Farmville, Virginia.” Even “The Negroes of Farmville, Virginia” (Du Bois Reference Du Bois1898a), a short (38 pages) and sole-authored study, exemplifies Du Bois’s ‘all hands on deck’ data strategy. The study was primarily based on a survey that Du Bois conducted in the community during July and August 1897, with reported numbers of observations varying around 1200. Du Bois (Reference Du Bois1898) included the interview schedule in the text of the “Farmville” article, shown here as Fig. 1. As the figure relays, survey questions included queries about basic demographics (age, sex, family size and configuration); residential history; educational background; work and occupations; and church attendance. The study also included data from the U.S. Census, Germany, Ireland, and France, and a supplemental survey of an all-Black district called Israel Hill (n = 123). The Israel Hill supplement demonstrates that Du Bois was not afraid of small sample sizes, owing to his inductive and descriptive approach to quantitative analysis. This practice is consistent with the tenet of exploratory data analysis that “patterns need not be ‘large’ to be noteworthy” (Jebb et al. Reference Jebb, Parrigon and Woo2017, p. 266).

Figure 1. Interview Schedule from “The Negroes of Farmville, Virginia” (Du Bois Reference Du Bois1898a, p. 7)

The Philadelphia Negro. The Philadelphia Negro (Du Bois Reference Du Bois2007b [1899]) included a survey of 9675 residents and their residences in Philadelphia’s Black Seventh Ward. This seminal text is noteworthy for the degree of saturation that Du Bois achieved in this area of approximately one-third of a square mile: he visited all Black households in the ward, sometimes returning on multiple occasions if a family was not home the first time. The family interview schedule for The Philadelphia Negro (Reference Du Bois2007b [1899]) included many of the same questions as the one Du Bois used in Farmville (compare Du Bois Reference Du Bois1898a, p. 7 and Du Bois Reference Du Bois2007b [1899], Appendix A). Additions for the expanded survey in Philadelphia included questions about health (“[S]ound and healthy in mind, sight, hearing, speech, limbs and body?”) and a systematic instrument to collect data on a household’s weekly, monthly, and yearly expenditures. He described his data collection procedures in detail:

Seated then in the parlor, kitchen, or living room, the visitor began the questioning, using his discretion as to the order in which they were put, and omitting or adding questions as the circumstances suggested. […] From ten minutes to an hour was spent in each home, the average time being fifteen to twenty-five minutes. Usually the answers were prompt and candid, and gave no suspicion of previous preparation. In some cases there was evident falsification or evasion. In such cases the visitor made free use of his best judgment and either inserted no answer at all, or one which seemed approximately true (Du Bois Reference Du Bois2007b [1899], pp. 40-41).

Du Bois ultimately surveyed or otherwise triangulated demographic data for, by his account, nearly every Black resident of the ward. He also collected separate surveys on house servants and institutions in the ward, as well as on the physical condition of homes and streets. This level of comprehensiveness speaks to his insistence on seeing a Black community in its totality as well as his emphasis on quantification, committed as he was to “the most careful and systematic study” (Du Bois Reference Du Bois1898b, p. 1) of social life in general and Black social life in particular.

Du Bois’s portrait of turn-of-the-century Philadelphia was also deeply historical and comparative. The accumulation of racialized identities and spaces over two-and-a-half centuries is foundational to his theoretical approach (Loughran Reference Loughran2015, Reference Loughran, Morris, Allen, Johnson-Odim, Green, Hunter, Brown and Schwartz2022). Particularly in the context of accelerating migration from the South and rural areas in the late 1800s, his emphasis on generations reflected his understanding that the social construction of Black identity was shaped by time and space, a clear pushback against White perspectives that saw race as biological and that saw Black people as a monolith: “A generalization that includes a North Carolina boy who has migrated to the city for work and has been here for a couple of months, in the same class with a descendant of several generations of Philadelphia Negroes, is apt to make serious mistakes” (Du Bois Reference Du Bois2007b [1899], p. 51). Du Bois also weighed Philadelphia’s Census data against the largest “chocolate cities” (Hunter and Robinson, Reference Hunter and Robinson2018) in the late-nineteenth-century United States, including Baltimore, St. Louis, and Cincinnati, and compared local health statistics with those from England, France, Germany, Austria, Hungary, and Italy.

The Negro Artisan. The Atlanta University Publication The Negro Artisan (Du Bois ed. Reference Du Bois1902) was similarly comprehensive. The study was based on a survey of Black skilled laborers in Georgia (n = 1300); additional surveys conducted by college-educated Blacks (i.e., Atlanta conference correspondents) of their own states, resulting in coverage of thirty-two states; surveys of every trade union affiliated with the American Federation of Labor (n = 97), central labor bodies of “every city and town of the Union” (n = 200 across thirty states), state federations, and a survey on business establishments in the South jointly conducted with the Chattanooga Tradesman; and surveys of Black industrial schools (n = 60), “Superintendents of Education in all the Southern States,” and children in the Atlanta public schools (n = 600). The study also drew on supplementary data from the U.S. Census, Bureau of Education, and various supporting documents, such as Black industrial schools’ course catalogues.

Analytic Strategies: Description, Within- and Between-Race Comparison, and Intersections

With such data in hand, Du Bois thickly described empirical patterns with varying combinations of within- and between-race comparisons carried out across historical time and geographic space. Besides race, his key comparative axes included, but were by no means limited to, gender, social class (particularly income), age, (il)literacy, occupation, and family/ household size. Du Bois’s quantitative work also stretched well beyond the individual level, including results on schools and colleges, churches, neighborhoods, businesses, and farms, among myriad other social institutions and units of observation.

Reading Du Bois’s quantitative work is to encounter a sheer litany of data presented in tabular form, as he seamlessly transitions between—or just plain-old mashes together— information from his many data sources. Francis Galton and Karl Pearson were still working towards regression and correlation at the turn of the twentieth century, with notable publications from each author appearing in 1894 and 1896, respectively (c.f., Stanton Reference Stanton2001). We are therefore not surprised that Du Bois’s research, published around the same time, did not rely on these techniques. Du Bois did, however, often conduct and interpret multivariable analyses based on multidimensional contingency tables, and we discuss many such analyses below. Multiple examples we discuss below also evidence Du Bois’s careful attention to missing and fallible data.

“The Negroes of Farmville, Virginia.” A table in “The Negroes of Farmville, Virginia” (Du Bois Reference Du Bois1898a), “Percent in Different Age Periods of Negroes in Farmville and of Total Population in Various Countries” (reproduced here as Fig. 2) exemplifies this approach. The table breaks down, by categorical age brackets, the populations of Farmville from Du Bois’s primary data collection; the “colored” and total populations of the United States, from Census data; and the populations of Germany, Ireland, and France, from a reference volume. Du Bois trains his eye on Farmville’s relatively low proportions of residents between the ages of twenty and twenty-nine and thirty and thirty-nine, compared to the same categories in the five other geographic aggregations. For example, only 9.79% of Farmville’s residents are between thirty and thirty-nine, compared to 11.26% for the “colored” population of the United States and 13.48% for the total population of the United States, and 12.7% in Germany. He explains:

[H]ere again we have evidence of the emigration of persons in the twenties and thirties, leaving an excess of children and old people. This excess is not neutralized by the immigration from the country districts because that immigration is apt to be of whole families…The proportion of children under 15 is also increased by the habit which married couples and widowed persons have of going to cities to work and leaving their children with grandparents. This also accounts for the small proportion of colored children in a city like Philadelphia (Du Bois Reference Du Bois1898a, p. 9).

Figure 2. “Per Cent in Different Age Periods of Negroes in Farmville and of Total Population in Various Countries” from “The Negroes of Farmville, Virginia” (Du Bois Reference Du Bois1898a, p. 9)

Du Bois’s interpretation evidences his awareness of how Black family migration into and out of Farmville shaped its age pyramid. It also shows that he had been thinking about how the relatively fewer children that he was noticing in his contemporaneous data collection in Philadelphia was related to his observations in Virginia. Lastly, Du Bois’s (Reference Du Bois1898a) interpretation also considered the possibility for inaccurate data: “[W]ith regard to persons 35 or 40 years of age or over, there is undoubtedly considerable error in the age returns. They do not know their ages, and have no written record. In such cases the investigator generally endeavored, by careful questioning, to fix some date, like that of Lee’s surrender, and find a coinciding event like marriage or the ‘half-task’ child labor period of life, to correspond” (p. 9).

The Philadelphia Negro. In The Philadelphia Negro (Du Bois Reference Du Bois2007b [1899]), the intersection of race and class looms large for Du Bois, consistent with the fact that he “saw class and race as profoundly fused in the make-up and dynamics of social life” (Bobo Reference Bobo2015, p. 466). He attended to class differences within the Black community, given racialized economic and occupational systems, as well as White observers’ assumption that the city’s Black population was homogeneous. As part of this analysis, Du Bois compared the labor force participation of Blacks in the Seventh Ward to the whole population of Philadelphia, noting Seventh Ward Blacks’ higher rates of working (78%) than the comparison group (55%), “an indication of an absence of accumulated wealth, arising from poverty and low wages” (Reference Du Bois2007b [1899], p. 78).

Du Bois (Reference Du Bois2007b [1899]) further pointed to how racial differences in class standing were also gendered, providing results on labor force participation in Philadelphia broken down by race, nativity, and gender (see our Fig. 3). His interpretation of these categories’ interrelationships focused on Black women’s especially high rate of labor force participation and how it was tied to Black men’s economic standing:

Among the men low wages means either enforced celibacy or irregular and often dissipated lives, or homes where the wife and mother must also be a bread-winner. Statistics curiously illustrate this; 16.3 percent of the native White women of native parents and of all ages, in Philadelphia are breadwinners; their occupations are restricted, and there is great competition; yet among Negro women, where the restriction in occupation reaches its greatest limit, nevertheless 43 percent are bread-winners, and their wages are at the lowest point in all cases, save in some lines of domestic service where custom holds them at certain figures; even here, however, the tendency is downward (Du Bois Reference Du Bois2007b [1899], p. 78).

Figure 3. “The Working Population of Philadelphia, 1890” from The Philadelphia Negro (Du Bois Reference Du Bois2007b [1899], p. 78)

Scholars have contested Du Bois’s relationship to intersectionality (compare Collins Reference Collins2000 and Hancock Reference Hancock2005), and resolving those disputes is beyond our scope here. Du Bois’s analyses of intersections and overlaps between race, class, gender, and other statuses are, at least indirectly, resonant with what Leslie McCall (Reference McCall2005) has referred to as an “intercategorical” approach to intersectional methodology—systematically comparing relationships within and between existing categories (p. 1786). As an alternative to intersectionality, one could position Du Bois within a more general push in inequality or ‘gaps’ research to make sure that results are “broken down by race and gender” (Leicht Reference Leicht2008), which does not claim a direct relationship to intersectionality. This aspect of Du Bois’s quantitative work also provides an early example of disaggregation approaches that are today used to analytically leverage heterogeneity within the Black population, such as by nativity, to better understand the processes leading to racial disparities in social outcomes (e.g., Ifatunji et al., Reference Ifatunji, Faustin, Lee and Wallace2022).

Moving beyond the individual level of analysis, Du Bois’s study of Black churches in the chapter “The Organized Life of Negroes” (Chapter 7) in The Philadelphia Negro is a quintessential example of his institution-level quantitative work. Understanding that occupational and educational advancement for Black people were limited by racism, Du Bois sought to quantitatively examine how class differences in the Seventh Ward manifested through cultural institutions and related cultural mechanisms, chiefly including the Black church. His survey included questions on church affiliation, and he obtained detailed financial data on Black churches in the Seventh Ward and beyond. Among other findings, this descriptive information showed how perceived class differences between the city’s African Methodist Episcopal congregations and its Black Baptist congregations, thought to be to the Methodists’ advantage, were more a question of cultural than economic capital. Black Baptist churches owned property that was worth 47% more than the African Methodist Episcopal churches (see Fig. 4).

Figure 4. “Colored Baptist Churches of Philadelphia, 1896” from The Philadelphia Negro (Du Bois Reference Du Bois2007b [1899], p. 150)

Du Bois’s study of Black churches yet again demonstrates how he was not afraid of missing data and often interrogated missingness as a finding in and of itself. As shown in Fig. 4, some Black Baptist churches were missing data on some or all variables of interest (indicated in our Fig. 4 by “…”), which was much less often the case for Black Methodist churches. On this score, Du Bois (Reference Du Bois2007b [1899]) argued that Baptists were “quite different in spirit and methods from the Methodists; they lack organization, and are not so well managed as business institutions. Consequently, statistics of their work are very hard to obtain, and indeed in many cases do not even exist for individual churches” (p. 151).

The Negro Artisan. Results in The Negro Artisan (Du Bois ed. Reference Du Bois1902) also evidence Du Bois’s 1) multilevel analytic framework encompassing Blacks as individuals, as well as the social institutions they formed and inhabited, and 2) his focus on intersections of race with other characteristics, including place, conceptualized and studied in Artisan across multiple levels of aggregation. To the first point, Artisan includes a section on Black industrial schools titled “Cost of Industrial Training,” based in part on data from the U.S. Commissioner of Education, 1899–1900. As shown in Fig. 5 (which is truncated from the original), Du Bois compiled statistics for Black industrial colleges that included enrollment; value of buildings and property; and income from gifts, state aid, tuition, interest, and other sources. The truncated figure shows, among other patterns, how Booker T. Washington’s ‘Tuskegee Machine’ held a dominant resource position among Black industrial schools, with a physical plant valued at $252,319 and, consistent with Washington’s links to White philanthropists, an income from “gifts” in the focal year ($97,231) that dwarfed that of all other Black industrial schools, with the lone exception of Hampton (physical plant valued $757,000 and gifts valued $254,333, not shown in figure).

Figure 5. “Income of Industrial Schools, 1899-1900” (Truncated from Original) from The Negro Artisan (Du Bois ed. 1902, p. 66)

However, statistics on Black industrial schools from national data did not fully satisfy Du Bois’s curiosity. He therefore sent a survey directly to all ninety-eight Black industrial schools in the country:

[E]very school in the country which is especially designed to give industrial training to Negroes was sent the schedule of questions printed on page 11. Of the 98 thus questioned 44 answered, and partial data were obtained from the catalogues of 16 others, making returns from 60 schools in all. Of these sixty a number answered that they were unable to furnish exact data or had no graduates working as artisans (Du Bois Reference Du Bois1902, p. 69).

The chapter then provides information on artisans from each school, at a painstaking level of detail. For example, at the aforementioned Hampton, 227 graduates completed trades from 1885–1902, “[O]f these 10 are dead, and 42 not heard from. Of the remining 161 heard from, 139 are working at their trades or teaching them” including, taking a few categories, twenty-six blacksmiths, four bricklayers, and seventy-four carpenters (Du Bois ed. Reference Du Bois1902, p. 70). From these results, Du Bois (ed. 1902) outlined five faults and five accomplishments of Black industrial schools. Faults included the schools’ work costing too much, while accomplishments included “co-ordination of hand and head work in education” (p. 83).

Whereas “The Negroes of Farmville, Virginia” (Du Bois Reference Du Bois1898a) and The Philadelphia Negro (Du Bois Reference Du Bois2007b [1899]) are primarily hyper-local, sections of The Negro Artisan (Du Bois ed. Reference Du Bois1902) make clear that Du Bois also used national data in his work, taking his hallmark comprehensiveness nationwide. Beyond his nationwide survey of Black industrial schools, a section of Artisan titled “[G]eneral Statistics of Negro Artisans” further illustrates: Using Census data from 1890, Du Bois first broke down the number of Black artisans in each state by gender and occupation. He then broke these patterns down further, to the city level: “[W]e may further study the Black artisan by noting his distribution in the large cities where most of the White artisans are located. For this purpose let us take 16 large cities with an aggregate Negro population of nearly half a million” (Du Bois ed. Reference Du Bois1902, p. 89). These results (see our Fig. 6) revealed “many curious differences” in the distribution of Black artisans between cities, such as relatively few, besides barbers, in the northern cities of New York, Chicago, and Cincinnati, but higher representation of Black artisans in cities in border states and in the south.

Figure 6. “Skilled Negro Laborers (by Cities)” from The Negro Artisan (Du Bois ed. Reference Du Bois1902, p. 90)

Conclusion: In Defense of Du Boisian Quantification

Returning to the question we posed at the outset: was W. E. B. Du Bois a quant? Our exploration of Du Bois’s quantitative methodology has unfolded within a surge of interest in his sociological oeuvre more broadly. The papers and books that have succeeded foundational recent works by Aldon Morris (Reference Morris2015), Reiland Rabaka (Reference Rabaka2010), José Itzigsohn and Karida Brown (Reference Itzigsohn and Brown2020), and Earl Wright II (Reference Wright2016) form what we term the New Du Boisian Sociology. Most sociologists today agree that Du Bois was, at minimum, an important classical sociologist whose work should be read, taught, and remembered. In that respect, the New Du Boisian Sociology has been unequivocally successful in shaping sociology’s current understanding of Du Bois.

We have argued that a productive next step for the New Du Boisian Sociology is to take a methodological turn—encouraging work that is not only spiritually inspired by Du Bois but that seeks to do sociological research in the manner that he did. The New Du Boisian Sociology and related bodies of prior scholarship about Du Bois do feature some attention to his methodology, including broad agreement that he utilized a mixed-methods triangulation approach to understand and combat structural racism and, simultaneously, develop a scientific sociology. Building on this work, we have brought forward a deeper and more specific engagement with Du Bois’s quantitative methodology, with an eye towards challenges and opportunities for contemporary applicability. During the height of his sociological research program at the turn of the twentieth century, Du Bois initiated an inductive, descriptive, and empirically comprehensive quantitative approach. Du Bois’s quantitative methodology, at first glance, diverges from celebrated works like The Souls of Black Folk (Du Bois Reference Du Bois1994 [1903]) and Black Reconstruction (Du Bois Reference Du Bois1935). It also diverges from the mainstream of quantitative sociology as it is practiced today.

In an era of racist and pseudoscientific speculation about Black people, Du Bois amassed data from specific localities, albeit ones he hoped were reasonably representative, to spur hypotheses and generalizations that he hoped would be fleshed out in subsequent research, including his own, although he did not fully realize these goals due to resource constraints and his increasing desire to engage in direct activism (Williams Reference Williams2006). He leveraged descriptive quantitative data to support a Black liberation sociology and contribute to the understanding of how race was “related to other social processes and examining the form of this relationship beyond that involved in the data under analysis” (Zuberi Reference Zuberi2001, p. 91). Today, echoes of the structural conclusions drawn from quantitative data can be found, among other places, in studies that seek to quantify systemic racism across various domains of social life. Research on racial disparities in health is one area where these approaches are gaining traction, and it is not surprising that some of this work cites Du Bois as foundational (see, e.g., Brown and Homan, Reference Brown and Homan2022).

Du Bois’s research agenda of using his studies to contribute to positive social change for Black people contributed to his methodological choices including his quantitative methods (Bobo Reference Bobo2014; Morris Reference Morris2023; Williams Reference Williams2006; Zuberi Reference Zuberi2001). As Lawrence D. Bobo (Reference Bobo2014) writes in the introduction to the 2014 edition of the The Philadelphia Negro: “[Du Bois] did not pursue science for science alone. Du Bois saw his scholarly work as intimately linked to the task of reform and social change so desperately needed by blacks in his time” (pp. xxvi-xxvii). Du Bois’s early quantitative work, therefore, integrated the concerns and methods of the reform-minded and geographically-specific social survey of the late nineteenth century—also exemplified, for example, by the work of Charles Booth in London and Florence Kelley and her Hull House colleagues in Chicago—with the goal of scientifically understanding society (Bobo Reference Bobo2014; Bulmer Reference Bulmer, Bulmer, Bales and Sklar1991b).

However, as Du Bois was leaving his sociological laboratory at Atlanta for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), elite U.S. academic sociologists consolidated ownership over efforts to scientifically understand society and distanced themselves from turn-of-the-century reform movements, including their key research tool of the social survey (Bulmer Reference Bulmer, Bulmer, Bales and Sklar1991a). Elite academic sociology’s preferred research method was the sociological survey and its accompanying logic of hypothesis testing. As the University of Chicago’s Robert Park wrote in 1926, “[s]ocial research, in the strict scientific sense, is confined to investigation based on hypotheses…a [social] survey is never research—it is explorations; it seeks to define problems rather than test hypotheses” (quoted in Bulmer Reference Bulmer, Bulmer, Bales and Sklar1991a, p. 303). Du Bois’s inductive quantitative approach—nested within his intertwined research goals of improving Blacks’ life chances and, in doing so, better understanding the relationship between Chance and Law within a formal sociology—falls straight through the cracks of Park’s forced and false dichotomy.

We would be remiss not to acknowledge that Du Bois sometimes used quantification and comparison to support ideas and interpretations that have not aged well. “The Negroes of Farmville, Virginia” (Reference Du Bois1898a) provides one example. Du Bois’s community survey research noted:

[A]bout 45 or 50 families of Negroes who are below the line of ordinary respectability, living in loose sexual relationship, responsible for most of the illegitimate children, chief supporters of the two liquor shops, and furnishing a half-dozen street walkers and numerous gamblers and rowdies…These slum elements are not particularly vicious and quarrelsome, but rather shiftless and debauched. Laziness and promiscuous sexual intercourse are their besetting sins (p. 37).

Du Bois’s research features occasions where his desire to see Blacks progress socially and economically combined with his Victorian morals and resulted in conclusions—particularly about the most economically disadvantaged Blacks in comparison to their more advantaged peers—that passed judgment on individual behaviors with inadequate acknowledgement of structural conditions. He often used numbers to drive home these unfortunately moralistic comparisons (Higginbotham Reference Higginbotham1993; Williams Reference Williams2006; Zuberi Reference Zuberi2001).

Our work here is not without limitations, which represent useful directions for future research. We have intentionally limited our analytic scope to a productive period around the turn of the twentieth century that clearly illustrates Du Bois’s quantitative methodology and its implications for academic sociology. We have therefore studied quantitative inquiry in what could be termed Du Bois’s ‘first wave.’ Opportunities for future scholarship in this vein include comparing and contrasting Du Bois’s quantitative approach with his historical and phenomenological approaches; considering how Du Bois utilized quantification in Black Reconstruction (1935) and other, later work; and mapping out how potential changes in his empirical methodologies related to his well-documented epistemological and political shifts during seven decades of scholar-activist output (Lewis Reference Lewis2000; Itzigsohn and Brown, Reference Itzigsohn and Brown2020). For reasons of space, we have also omitted an analysis of the innovative data visualizations that Du Bois developed during our time period of study, for instance the plates he created for the 1900 Paris Exposition (recently detailed in Battle-Baptiste and Rusert eds., Reference Battle-Baptiste and Rusert2018). We note that this aspect of Du Bois’s quantitative work also fits squarely within an exploratory data analysis approach, which also emphasizes data visualization as a means of data analysis.

Another important task for future research on Du Boisian quantification is to investigate whether and how it might be useful to put him into conversation with formal definitions of probability and sample-to-population inference. While beyond the scope of our study, this work can build on ours and further connect Du Bois’s quantitative methodology to contemporary quantitative analysis and reporting practices. Within the philosophy of statistics, scholars often align Bayesian approaches with inductive logics and frequentist approaches with deductive ones (but see Gelman Reference Gelman2011). It is therefore possible, although by no means certain, that a Du Boisian quantification approach suggests and is compatible with a Bayesian notion of probability.

Sociologists who want to embrace a Du Boisian quantitative approach in some or all of their research face two current barriers. First, based in part on the historical lineage sketched earlier, quantitative sociology currently upholds a “gold standard” for publication and funding that prioritizes varying combinations of deductive theory testing, experimental or quasi-experimental methods, and causal inference (see, e.g., Saiani Reference Saiani2018; Sampson Reference Sampson2010). To be clear, we are not against deductive and/or causal research. The standard is problematic only to the extent that it marginalizes exploratory, descriptive, and inductive approaches that we have identified here as in line with Du Boisian quantification. When engaged systematically and rigorously, inductive-exploratory and deductive-confirmatory approaches should mutually inform and strengthen each other within a well-functioning wheel of quantitative social science (Gelman and Loken, Reference Gelman and Loken2014; Tukey Reference Tukey1980).

A relative lack of emphasis on descriptive research also harms sociological theory. If we care about sociological theory and quantitative research’s contributions to it, we need more descriptive research. As Max Besbris and Shamus Khan (Reference Besbris and Khan2017) argue: “An ideal scientific discipline might be envisioned as a pyramid, built on a firm basis of description, with a smaller amount of reevaluation, and even less theorization. Yet sociology too often reverses this pyramid. Sociology is a theoretically demanding discipline that, because of its constant demands for theorization, is theoretically impoverished” (p. 152). A growing embrace of Du Boisian quantification is one of many possible means to the end of more descriptive research. The exploratory data analysis approach with which we have identified Du Bois similarly notes that a lack of description, or “phenomenon detection” blunts subsequent theory development, arguing, “theory may be the overarching ‘story,’ but phenomena are the ever-important words with which it is written” (Jebb et al., Reference Jebb, Parrigon and Woo2017, p. 265). This type of descriptive, empirically driven work, after all, helped Du Bois develop the theoretical frame of racialized modernity (Itzigsohn and Brown, Reference Itzigsohn and Brown2020) that continues to inspire sociologists more than a century later.

The second barrier confronting those who wish to embrace a Du Boisian quantitative approach in some or all of their work is our own present-day ‘battle of methods’ (to borrow the description of the European academy during Du Bois’s years at Berlin) in sociology and other disciplines. Current disagreement is over quantification’s productive role, if any, in research on racism, class domination, heteropatriarchy, and other types of systemic inequity, analyzed separately or intersectionally. On one hand, a growing “quantcrit” (Garcia et al., Reference Garcia, López and Vélez2018; López et al., Reference López, Erwin, Binder and Chavez2018) movement is working to square quantitative approaches with critical theories and cites Du Bois, among others, as precedent that this can be done. Nichole Garcia and colleagues (Reference Garcia, López and Vélez2018) write that “Du Bois was key to the development of thick descriptions of the relationships of power at the individual, institutional, and structural levels that generated inequities adversely affecting Blacks” and “made a major contribution to the deracialization of statistics by challenging eugenicist assumptions…” (p. 152). On the other hand, some remain concerned that when it comes to quantitative research, “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house” (Bowleg Reference Bowleg2008, Reference Bowleg2021 quoting Lorde Reference Lorde1984). While not necessarily dismissive of quantitative research, this line of thinking is skeptical of its assumptions and tends to favor qualitative methods or qualitative-driven mixed methods approaches (Bowleg Reference Bowleg2008).

Du Bois offers a third way. His description of systemic inequities facing Blacks, written in “The Study of the Negro Problems” in 1898, unfortunately still resonates with our present moment, for Blacks as well as for other marginalized groups: “[i]t is not one problem, but rather a plexus of social problems, some new, some old, some simple, some complex…” (Du Bois Reference Du Bois1898b, p. 3, italics in original). If his description resonates, so too should his scientific example—using rigorous inquiry to better understand inequality’s forms and sources, in hopes of contributing to lasting social change. Du Bois’s published work includes qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods products; the mixed-methods work features, among other types, quantitative investigations where qualitative observation plays only a supplementary, informal, and anecdotal role (see, e.g., “The Negroes of Farmville, Virginia,” Du Bois Reference Du Bois1898a, p.7, note a). Today’s battle of methods is, simply put, at odds with a Du Boisian approach. If we are to follow his example, we too should champion the use of any and all methodological tools at our disposal to meet our moment, as Du Bois did in order to meet his.

Acknowledgement

For helpful feedback on this manuscript, we thank Aldon Morris, Kim Goyette, the editor and anonymous reviewers at DBR, and seminar participants at the 2023 Annual Meeting of the Association of Black Sociologists, the 2023 Annual Meeting of the American Sociological Association, and the Economic and Social Inequality Working Group in the Department of Sociology at the University of Texas at Austin. Any errors or omissions are our own.