I

In recent years, a flourishing interest in gender as an essential category of analysis has met a growing need for a historiography that could draw a more detailed picture of credit markets in past societies. The role of women as borrowers and lenders, their freedom to function as independent economic actors and the nature of the economic exchanges in which they were involved, are just some of the issues currently debated by economic and social historians. However, to study gender relations through history poses a tough challenge to scholars, who have to face both the scarcity of sources and the difficulty linked to a correct interpretation of those in their possession. Moreover, the superimposition of an uneven judicial, religious and traditional normative framework further complicates comparisons at a European level, and generalisations can sometimes be problematic.

Men and women played different roles in the credit market. The theory of the separate spheres sees women relegated to a purely private dimension, that of the household, while men were at the centre of the public one. Women were not considered to be active in the market and their role was limited to providing men with moral support, while the latter invested the family resources (Rutterford and Maltby Reference Rutterford and Maltby2006, p. 112). Of course, this is an incomplete and imprecise vision of gender relations that has been gradually overcome. In fact, it has been proved that women participated widely in the financial market. They have often been described in the literature as being more conservative than men, as they usually chose assets that presented a lower risk but offered a secure return (Carlos and Neal Reference Carlos and Neal2004; Rutterford and Maltby Reference Rutterford and Maltby2006, p. 113; Petersson Reference Petersson, Laurence, Maltby and Rutterford2009, p. 261). At the same time, they also proved to be very active and wise traders since, despite the lower risks, they often managed to get globally higher returns than men (Carlos, Maguire and Neal Reference Carlos, Maguire, Neal, Laurence, Maltby and Rutterford2009; Laurence Reference Laurence, Laurence, Maltby and Rutterford2009).

Women seem to have been able to manage effectively their large or small assets, on which in some cases their very survival depended. Regarding the case in England, Green and Owens (Reference Green and Owens2003) proved that they were ‘at the centre of a system of public finance that provided the government with revenues for imperial expansion and warfare’ (p. 524). In fact, women were important investors in government debt: in 1840, as much as 40 per cent of all fund holders were female, 19 per cent of whom were spinsters and 13 per cent widows (Rutterford and Maltby Reference Rutterford and Maltby2006, p. 122). It has to be highlighted that this was an increasingly complex financial world, proving that they were skilled players with access to a considerable amount of knowledge and information (Green et al. Reference Green, Owens, Swan, Van Lieshout, Green, Owens, Maltby and Rutterford2011, p. 77).

The aim of this study is to measure the actual extent of female engagement in the credit market in Sweden throughout the long nineteenth century, a period of strong industrial and financial development for the country. It aims to help fill a gap in the literature, since there still are few works focused on women and credit in Scandinavia. While the evolution of the Swedish economy and financial market during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries has been at the core of numerous studies, the effects of this phenomenon from a gender perspective still need to be better investigated. It is not just a matter of gauging the quantitative presence of women in the market, but rather of investigating how their credit activity varied over time, as the market was evolving, becoming more and more institutionalised (Lindgren Reference Lindgren2002).

In order to do that, this research relies on more than 1,900 probate inventories collected in the Swedish cities of Gävle and Uppsala in seven surveys between 1790 and 1910 (a survey every 20 years). Uppsala and Gävle represent ideal case studies and offer possibilities for an interesting comparison. In fact, the two cities proved to have quite differently structured credit markets because their formalisation through the establishment of new financial institutions took place in dissimilar ways. In Uppsala, the establishment of new banks seemed to have been delayed by the presence of a ramified network of private lenders; on the other hand, in Gävle the pre-bank credit market was not as developed, and this favoured the process of formalisation.

Women's economic lives and their patrimonial strategies are greatly influenced by their marital status. In particular, it is well known that spinsters, widows and married women not only had diverse property rights, but also enjoyed different degrees of freedom in managing their own assets. They all participated in the labour and credit markets but the kind of relationship they established with them was markedly dissimilar (Bennett and Froide Reference Bennett, Froide, Bennett and Froide1999; Ågren Reference Ågren2009; Spicksley Reference Spicksley and Dermineur2018). This is why this study considers each category of women separately – spinsters, married and widows – and compares them to each other.

The study of women, credit and marital status implies also a consideration of the evolution of property rights, and the complicated laws concerning both married and unmarried women, especially spinsters. These legal changes had a large impact on the possibility of them supporting themselves with an acquired wealth, in particular during the second half of the nineteenth century. This research is therefore at the crossroads between many critical topics, for example property rights, financial knowledge and female emancipation, and it dialogues with a substantial literature that assesses the economic activities of unmarried and married women in different European contexts, especially studies focused on Britain and the Netherlands.

Spinsters, married women and widows have already been at the core of numerous studies, some of which focused on the Scandinavian context. Anders Perlinge defined Stockholm as the ‘capital of maids’, indicating both the number of unmarried female inhabitants and the importance of their private fortunes (Perlinge Reference Perlinge2018, p. 30). He proved that even though there were obstacles of both an institutional and a cultural nature, these women were in fact ‘investors and shareholders of their own right in a variety of limited liability companies or in government bonds’ (Perlinge Reference Perlinge2018, p. 21). However, as we will see also in this article, it seems to be true that spinsters – and also widows – preferred slightly conservative and risk-averting investment, appearing only rarely as borrowers (Petersson Reference Petersson, Laurence, Maltby and Rutterford2009, p. 263).

According to the Swedish Civil Code of 1734, widows could enjoy full legal rights from an economic point of view, making them totally comparable to men (Holmlund Reference Holmlund, Morell and Bock2008, p. 240; Petersson Reference Petersson, Laurence, Maltby and Rutterford2009, p. 258). The literature focused on England proves that they were heavily involved in all forms of credit, in both the institutional and peer-to-peer credit market (Holderness Reference Holderness and Smith1984; Spicksley Reference Spicksley and Dermineur2018). As we will see in the course of this article, this seems to be partially true in the Swedish case as well, at least in the two cities considered here. This is probably due to the fact that, on average, widows were richer than the other categories of women and therefore they invested their money in order to increase their revenue.

On the other hand, Maria Ågren (Reference Ågren and Dermineur2018, p. 124) highlights the fact that married women made up a large share of the total investors in Sweden. She claims that, despite the presence of regulatory constraints, in practice, married women enjoyed ample autonomy, ‘as they had greater freedom to manage their own resources, which were in fact separated from their husbands’’ (Ågren Reference Ågren and Dermineur2018, pp. 125–7). This is an important issue because it allows us to question the significance of credit as a tool of female empowerment and emancipation. However, the probate inventories of married individuals do not reflect an individual situation at the time of death, but that of the entire household (Moring Reference Moring2007). This is a much more critical problem in the case of married women because their assets, debts and credits were subsumed by those of their husbands (Bennett and Froide Reference Bennett, Froide, Bennett and Froide1999; Erickson Reference Erickson2005; Ågren Reference Ågren2009). This is why this article focuses more specifically on spinsters and widows, while married women will be considered just for comparative purposes.

As we will see in the course of the article, the different evolution of the financial system in Gävle and Uppsala had an effect on the behaviour of borrowers and lenders: in Uppsala, married women – therefore, married couples – are the most reactive in starting to deposit their money in banks, especially at the turn of the twentieth century. In Gävle, where the peer-to-peer credit market seems to be less developed, widows were the first to deposit their money in banks, probably because they needed to invest their money in order to get a source of income, followed by spinsters. Married women started opening bank accounts only after 1890, which seems to be a turning point in both cities. In general, while widows were to some extent involved in peer-to-peer credit, spinsters usually chose to deposit their money in both savings and commercial banks, and were almost absent as borrowers.

This article aims to retrace the behaviour of widows and spinsters in the credit market, as both creditors and debtors. Moreover, it aims to assess whether the development of the financial system strengthened the role of women as independent economic agents. To this end, it is divided as follows: Section II focuses on sources and methodology, analysing the composition of the sample under examination and giving a brief overview of the most important issues derived from the use of probate inventories. Section III centres on the problem of studying women's agency from probate inventories. It retraces the main characteristics of spinsters and widows as they emerge from probate inventories, and compares them with married women. Section IV analyses the behaviour of unmarried and married women in the credit market, focusing more specifically on banking and peer-to-peer exchanges (in particular, promissory notes). In order to do that, I will rely on the inverse mortality method, which allows one to adjust the sample according to the characteristics of the living population (in this case, the age structure). Section V briefly reviews the most important findings.

II

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the Swedish economy underwent a remarkable period of growth and transformation, during which the innovation of the financial system played a major role in supporting and fostering the industrialisation process (Sandberg Reference Sandberg1979; Magnusson Reference Magnusson2000; Ögren Reference Ögren2009, Reference Ögren2010a). The peer-to-peer credit market remained the most important source of funding for almost all of the nineteenth century, in the context of localised and fragmented markets (Petersson Reference Petersson, Laurence, Maltby and Rutterford2009, p. 256). Progressively, the introduction of banks favoured a more organised collection and redistribution of savings, and a more efficient allocation of capital. All these changes had very strong effects on the evolution of a financial system that has been defined as ‘both effective and inclusive’ (Petersson Reference Petersson, Laurence, Maltby and Rutterford2009, p. 265). Nevertheless, this process was not without contradictions and did not take place evenly across the country, as the cases of Uppsala and Gävle clearly show.

The two cities had a completely different structure and were characterised by dissimilar economies. The Baltic port of Gävle remained, over a long period, one of the most important in all of Sweden for the export of wood, copper and minerals. It was one of the most prominent merchant cities, home of many shipping companies and shipyards. Since the fifteenth century, Gävle had enjoyed the stapelrätt, the right to import and export to and from any international port, and it benefitted from this international role. The city grew fast throughout the nineteenth century, from about 5,000 inhabitants in 1790 to more than 35,000 in 1910. On the other hand, the city of Uppsala is located inland, about 70 km north of Stockholm. Uppsala had been the ecclesiastical centre of Sweden since the twelfth century and after the foundation of the University in 1477 – the oldest in the country – it also became the main cultural hub. It was one of the most important industrial centres and one of the biggest railway junctions in the country; it also benefitted from its proximity to the capital. As was the case for Gävle, the population increased in the course of the nineteenth century, growing from about 4,000 inhabitants in 1790 to almost 26,000 in 1910.

Probate inventories reflect – though in a partially distorted way – the profound changes affecting the two cities and, indeed, all of Swedish society in this period. They draw a vivid picture of the structure of the credit market, and of all the different alternatives it offered to borrowers and lenders. Not by chance, many scholars have focused on this kind of source as a tool for the study of economic and social history, in particular to retrace the impact of informal credit on industrialisation, or the changes in personal wealth and indebtedness in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries (see, for instance, Kuuse Reference Kuuse1974; Lindgren Reference Lindgren2002; on Finland, Markkanen Reference Markkanen1978).

The Swedish Civil Code of 1734 made it compulsory to draw up a probate inventory for each deceased person within three months of their date of death (Lindgren Reference Lindgren2002, pp. 816–18). The law established that heirs could be held personally liable for the debts of the deceased if they had unlawfully disposed of their inheritance before the inventory was arranged. According to Lindgren (Reference Lindgren2002, p. 818), this was one of the most important economic incentives to draw up inventories, even though just a proportion of the deceased had one.

This research is based on a sample of 1,909 probate inventories drawn up in Gävle (1,097) and Uppsala (811) between 1790 and 1910.Footnote 1 It contains all the inventories recorded in the two cities in seven different years, 1790, 1810, 1830, 1850, 1870, 1890 and 1910.Footnote 2 The structure and the size of the sample privilege the comparative perspective, while the long period considered allows us to measure the evolution of the credit market in the long term.

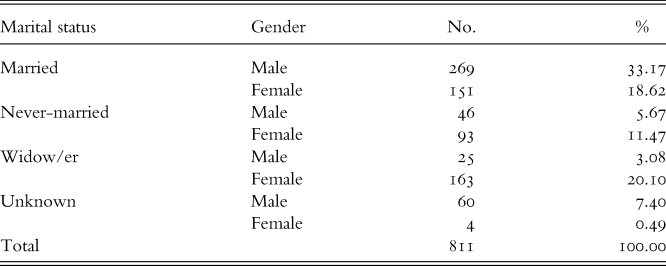

Among the inventoried decedents there are 188 spinsters, 95 in Gävle and 93 in Uppsala, and 368 widows, 205 and 163 respectively. Widows make up about 20 per cent of the entire sample, so are much more numerous than widowers (Tables 1 and 2). This could be explained by the fact that women usually live longer than men; it has also been proved that in early modern period widowers remarried more frequently than widows, who instead could not – or chose not to – do so because of their age or for other social reasons (Fauve-Chamoux Reference Fauve-Chamoux1998).

Table 1. Marital status sample composition, Gävle

Sources: see footnote 1.

Table 2. Marital status sample composition, Uppsala

Sources: see footnote 1.

At the same time, we also notice a great difference in the percentage of never-married individuals between the two genders. Widows and spinsters are much more numerous than widowers and bachelors, while the majority of men were married at the time of their death. As we can see in both tables, there is more missing data for men than for women, basically because of the nature of the source: probate inventories and civil registry almost always record the marital status of women, often also specifying names and professions of the husbands, while men's marital status is not always recorded.

Probate inventories are a rich source of information, but they also present some issues that need to be considered. The first problem is related to their representativeness compared to the living population, while the second concerns their potentialities in the study of women's agency. This section will focus on the first of these problems, and the following section on the second.

One of the most important issues that needs to be addressed when working with probate inventories is to assess how representative they are compared to the total living population. There are roughly two levels of representativeness, the first of which concerns the ratio between the number of inventories and deaths in a specific timeframe: how many of the deceased individuals actually have an inventory? To answer this question, we just have to compare the number of deceased people with that of inventories drawn up in the same year.

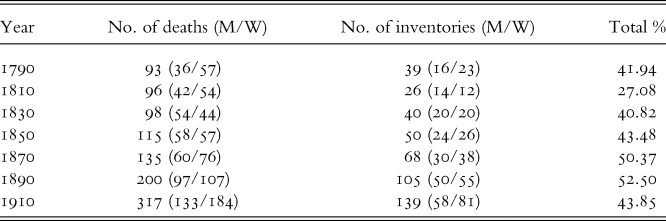

Even though the sample at the centre of this research includes all the inventories found regardless the age of the decedents, the representativeness test considers only those over 20 years of age when they died. In fact, the youngest decedents were only rarely economically independent, so there was no need to draw up an inventory (Lindgren Reference Lindgren2002, pp. 821–2): this explains why, if we consider just the younger decedents, the representativity falls to around 2–3 per cent of the total. The results of this analysis are described in Tables 3 and 4.Footnote 3

Table 3. Comparison between the number of inventories and deceased people (over 20 years old, Gävle) M: men W: women

Sources: see footnote 1; The Demographic Data Base, CEDAR, Umeå University (1790-1850); BiSOS årsberättelse 1870K, bilaga 1, s. 12; BiSOS 1890A, första delen, s. 23; BiSOS årsberättelse 1910K, bilaga 1, s. vii.

Table 4. Comparison between the number of inventories and deceased people (over 20 years old, Uppsala) M: men W: women

Sources: see footnote 1; The Demographic Data Base, CEDAR, Umeå University (1790-1850); BiSOS årsberättelse 1870K, bilaga 1, s. 19; BiSOS årsberättelse 1890K, bilaga 1, s. viii; BiSOS årsberättelse 1910K, bilaga 1, s. vi.

In Uppsala, data show a relatively stable representation, around 40–50 per cent of the total, while in Gävle we notice more inconsistencies (Table 3). In particular, in 1910 there seem to be more inventories than deceased individuals. By comparing the inventories with the 1910s register of deaths, I discovered that 14 names do not match, therefore highlighting a discrepancy in the data (census, probate inventories and dödböcker, the registers of the deceased). The most immediate explanation for this inconsistency would probably be migratory patterns: individuals moved, and it was sometimes difficult to keep track of everyone. Some of these individuals may have had debts in Gävle and, even if they did not reside or die in the city, their inventory was recorded anyway, to protect local creditors. Whatever the answer, it seems that the representativity in Gävle increased over time, with more and more individuals leaving a probate inventory after their death.Footnote 4 Finally, there do not seem to be particular differences between men and women, who are almost equally represented over the whole period.

Another type of bias that affects probate inventories concerns the socio-economic composition of the sample and how much it reflects the actual structure of the living population: briefly, are all social classes equally represented? Lindgren (Reference Lindgren2002) argues that those who had an inventory usually meet two main conditions: they had both assets to be listed and lenders claiming part of them (p. 819). He concludes that since the population detailed in the inventories had a certain wealth and was active in the credit market, it was proportionally richer than the average. In this respect, Keibek claims that although the number of households decreases in absolute terms according to their wealth, the probability of having the inventories of rich people increases progressively: this generates an overrepresentation of the higher social categories and an underrepresentation of the poorer ones (Keibek Reference Keibek2017, p. 13).

Indeed, probate inventories reflect a quite different social structure from that of the living population, dramatically evident especially among the upper and lower classes. For instance, members of the elite and of the local bourgeoisie (such as important merchants, university professors, etc.) are clearly overrepresented in the sample – they were 0.5–1 per cent of the total living population, and between 10 and 15 per cent in the sample of probate inventories. On the other hand, artisans, shopkeepers and those belonging to the lower level of society are dramatically underrepresented (59 vs 27 per cent).

To sum up, only about 40–50 per cent of the deceased population had a probate inventory, with a growing trend over time; moreover, older individuals belonging to the upper classes are generally overrepresented. This means that even though probate inventories are an extraordinary source, they describe the situation of just a small portion of the living population. Through the inverse mortality rate, it is possible to partially solve this problem and work with an age-adjusted sample, in which spinsters, widows and married women are considered singly and not as a generic group of ‘women’. Unfortunately, I cannot push forward the analysis and adjust the sample according to the social composition of the living population. In fact, the socio-professional status of women is not always indicated in the probate inventories and sometimes we do not even have that of their husbands/fathers. Moreover, even the demographic sources (like the Tabellverket)Footnote 5 often record women differently to men, and it is not possible to retrace their social strata.

III

The industrial and financial revolution engendered deep changes in Swedish society. First of all, wealth gradually increased over time, as did inequalities, peaking in the late nineteenth century (see Bengtsson et al. Reference Bengtsson, Missaia, Olsson and Svensson2018). The labour market and the socio-professional structure of society underwent a process of transformation that affected the ways in which individuals earned their wealth, and saved and invested it (Bengtsson and Prado Reference Bengtsson and Prado2020). These dynamics emerge clearly from the analysis of probate inventories, which, not by chance, contain the wealth accumulated by individuals in the course of their lives through their work, and that inherited from previous generations. It is easy to understand that in this regard men and women had dissimilar possibilities, primarily because of unequal inheritance and property rights. However, there were differences not only between the two genders but also within the category of women, according to their marital status.

At the beginning of the eighteenth century, the property rights of Swedish married women further deteriorated to the advantage of their husbands. In fact, the Code of 1734 made no distinction between the belongings of either spouse, and the marital estate became a unit of property at the husband's complete disposal. Swedish marital status, which had previously envisaged a bilateral property system, became closer to the British model, where a wife's belongings became the total and unconditional property of her husband (Ågren Reference Ågren2009, pp. 12–15). The situation for widows was slightly better, since after the death of their husbands they enjoyed the same full rights as men. Finally, spinsters could be controlled by their families or by a trustee, who managed their assets until the legal age, 25 years old from 1858, 21 from 1884 (Ighe Reference Ighe2007, p. 52).

In the second half of the nineteenth century, the situation for women seemed to improve, since we witness a profound transformation towards property and inheritance rights. In 1846, the inheritance law became more equal from a gender point of view and all children, regardless of their gender, had equal rights under law, thus inheriting the same amounts of both fixed and movable assets (Dribe and Lundh Reference Dribe and Lundh2005, p. 294; Holmlund Reference Holmlund, Morell and Bock2008, p. 240). Between the 1850s and 1880s, both married women and spinsters enjoyed more legal rights to possess and dispose of their property freely; however, this was just the starting point of a process that would reach its end only at the beginning of the twentieth century.

In general, it is not easy to retrace female participation in the credit market through probate inventories, mainly because of the scarce presence of women. In fact, even if the sample is almost equally divided between men and women, this does not mean that the two genders are equally represented. Probate inventories also include information about those individuals with whom decedents established debt or credit relations. From this perspective, the sample no longer concerns only 1,900 individuals but almost 16,000, who are involved in approximately 19,000 transactions. The gender distribution changes markedly and, considering the overall period, women appear as borrowers or lenders in less than 10 per cent of the total operations (9.18 per cent in Gävle and 9.15 per cent in Uppsala). However, these low percentages do not prove a low participation of women in the credit market stricto sensu, since they simply reflect another kind of representativeness issue: loans and debts were almost always registered under the name of the head of the family – usually a man – who was directly responsible for each member of the household.

Married women's assets, debts and credits were subsumed by those of their husbands, and it is complicated to establish exactly where the boundary separating the activity of each of the spouses lies. Widows’ inventories are partially affected by the same problem, since we do not know how much of what we find in their inventories has been ‘inherited’ from their husbands. Finally, as I have already stated, spinsters could have been influenced by their families, or by a trustee, who managed their assets until they reached the legal age. It is now clearer why the gender perspective is probably one of the most complicated aspects that could be analysed starting from post-mortem inventories. However, in the course of the article I will try to deal with this problem, at least for widows and spinsters, the two categories at the centre of the analysis.

An interesting question that may be answered by the analysis of the inventories is how the way individuals were described has changed over time, which could tell us something about the identification practices. In particular, I refer to the occupational classification of women. In most cases, the socio-professional status of a woman was subsumed under that of the householder – usually the father or husband – and his profession (daughter/wife/widow of … who is/was a …). In other cases, women were classified according to their social status, but usually only if they belonged to the elite or to the lower strata of society. To delve deeper, the specific case of spinsters is probably the most interesting to analyse (see Table 5).

Table 5. Number of spinsters listed with specific attributes (professional status, social status, etc.), Gävle and Uppsala, 1790–1810

Sources: see footnote 1.

In Gävle, the number of never-married women recorded as workers grew over time, and they are especially numerous in the inventories of 1890 and 1910. The majority of them were maids (28.72 per cent considering both cities), followed by seamstresses, some teachers and a nurse.Footnote 6 In Uppsala, the situation is slightly different: several spinsters worked since the 1830s, but their number does not increase as much as in Gävle between 1890 and 1910.Footnote 7 This trend suggests that the increase in the number of spinsters as probate inventory holders was perhaps a consequence of both the general enrichment of the society – with the rise of the middle class (Bengtsson and Prado Reference Bengtsson and Prado2020) – and the already mentioned increasingly equal judicial framework from a gender point of view.

On the other hand, the number of spinsters in the group ‘daughter of’, and therefore identified with the profession of their fathers, are just a minority of the total, especially in Uppsala. Being registered as ‘daughter of’ someone does not seem to be simply related to the young age of women, as the average age of those belonging to this group is 27.6 (considering both Uppsala and Gävle). More specifically, about a half of them (nine) were actually under 25, six of whom under 21: it is possible to suppose that those registered as ‘daughter of’ still lived in the same house as their parents, under the responsibility of a male householder, usually their father. Of course, this is just a hypothesis that needs further research, but, if true, it would confirm that the majority of spinsters in the sample (especially in Uppsala) were probably autonomous in the management of their assets, and were free in their investment strategies. In turn, this would suggest that most of what we find in their inventories is actually the result of their individual choice, and not that of external intervention.

Did the general industrial and financial revolution and the more increasingly homogeneous judicial framework have consequences for individual wealth? Looking at Figure 1, we would say yes, as the net wealth of married women, spinsters and widows grew in both cities over the nineteenth century (gross wealth has exactly the same trend). In Gävle, spinsters and widows became progressively richer over time after 1850, while in Uppsala this occurred only after 1870 (for widows) and 1890 (for spinsters), although more sharply. In both cases, the trend that characterises married women's wealth is similar to men's, something that further confirms that their inventories are almost superimposable.

Figure 1. Gross wealth, living population (age-adjusted sample), Gävle and Uppsala 1810–1910

Sources: footnote 1.

In this process of general enrichment, the weight of real estate in the total value of inventories may have played a decisive role because of the strong increase in land prices in the second half of the century (Bengtsson and Svensson Reference Bengtsson and Svensson2019, p. 132). This seems to be true in Gävle but not in Uppsala, where wealth was primarily composed of stocks, bank accounts and credits in the peer-to-peer credit market (we will delve deeper in the following section). This is further confirmation of the different structure of the economy of the two cities. However, the data used to build Figure 2 come from an age-adjusted sample, and age does not seem to be reliable in this specific case. In fact, the qualitative and quantitative evolution of wealth is much more affected by social differences than by simple demographic ones. Unfortunately, as I have already stated, it is not possible to adjust women's probate inventories with the living population from this point of view.

Figure 2. Value of real estate, age-adjusted sample, Gävle and Uppsala 1850–1910

Sources: see footnote 1.

In 1910, the number of spinsters and widows that belonged to the wealthiest part of society was bigger than ever before, and some of their probate inventories were incredibly rich. For instance, Johanna Helena Andersson was a spinster who died at 74 in Uppsala (on 4 June 1910). She has a total of 47 credit transactions recorded in her inventory: she lent more than 14,500 kronor to 15 different individuals, and at the same time she held five deposits in five different commercial banks, for a total amount of more than 42,000 kronor.Footnote 8 Johanna Helena was a woman who managed a considerable amount of money and carefully diversified her investments, as evidenced by the numerous deposits she placed in different banks.Footnote 9

Many widows also show marked entrepreneurial skills, as was the case with Johanna Carolina Åkerson (born Jonsson), who died on 19 June 1910 in Gävle. Her inventory is, in part, similar to that of Johanna Helena Andersson, as both of them managed large sums of money and appeared to have run important businesses. She seemed to be at the head of a trading company and her inventory is one of the richest in the entire sample, with a gross value of almost 900,000 kronor (indexed 1914). Åkerson lent money to individuals from different social classes, such as some farmers, and invested in funds and companies. She also deposited money in four different commercial banks and obtained loans from the same institutions for a total amount of over 270,000 kronor.Footnote 10 This was probably the result of a strategy designed to diversify her portfolio, but it could also testify to the pressure exerted by banks themselves, who were always looking for new, wealthy clients (Dermineur Reference Dermineur2021).

In order to better understand the real role that Johanna Carolina played in the family business, we can compare her inventory with that of her husband, Lars Vilhelm Åkerson, a merchant who died in 1893. When he died, Mr Åkerson had just one bank account at the Gefle Enskilda Bank (a commercial bank) containing about 12,900 kronor, and another 70,000 kronor generically defined as ‘at disposition’ (å deposition). The overall value invested in stocks was about 160,000 kronor, he possessed real estate amounting to more than 45,000 kronor, and other kinds of credit for 260,000 kronor.Footnote 11 The inventory of the widow Åkerson is very different from that of her husband. The amount invested in stocks increased by almost double, to a total of 400,000 kronor. The total value of the inventory grew considerably, as did that of liabilities, which were almost three times higher: this maybe testifies to a change in the management of the family business, a greater indebtedness aimed at favouring new investments (especially in stocks). Nevertheless, the overall net value of the inventory of the widow was almost 45,000 kronor higher than that of her husband, which means an increase of almost half a per cent a year.

Unfortunately, not even this kind of analysis allows us to clear our doubts concerning the role of widows in the management of business. In fact, the couple had six children, four daughters and two sons. Lydia and Edla Charlotta, the older daughters, were 29 and 27 when their father died, and they were probably already living with their husbands outside the family at that time. The elder son, Carl Vilhelm, was 24 at that time, and he could have played an important role in running the family business. This is a very interesting case, which proves once again how difficult it is to study household dynamics, and to understand the contribution and responsibility of each member. What is sure is that the death of the householder did not represent a problem for the Åkerson family, at least not from an economic point of view. In the course of the 17 years between the death of Lars Vilhelm and that of Johanna Carolina, the resources of the family increased consistently and it is clear that – whoever was responsible for this – there had been a change towards a more ‘aggressive’ management characterised by a strong indebtedness and investment in more diversified sectors.

IV

The Swedish banking sector experienced remarkable development during the nineteenth century, to such an extent that it has been referred to a real ‘financial revolution’ (Ögren Reference Ögren and Ögren2010b, p. 2). There are two types of institution that contributed the most to this process, namely savings and commercial banks. Savings banks were established for the first time in Sweden in the 1820s (the first savings bank in both Uppsala and Gävle dates back to 1824). They provided the working class an opportunity to save money, with the aim of encouraging the lower classes to save for hard times. For that reason, they were conceived to be relatively flexible and adapted to the various savings possibilities of their customers (Lilja Reference Lilja and Ögren2010, p. 45): they aimed at collecting as much capital as possible that was then reinvested in other productive activities. Unmarried women in their twenties were among savings banks’ preferred customers, because they ‘saved more than twice as much as men of the same age and marital status … and on a long-term basis’ (Petersson Reference Petersson, Laurence, Maltby and Rutterford2009, p. 261).

On the other hand, the right to establish commercial banks (known as Enskilda or private banks) was granted for the first time in 1824, when the Swedish government decided to allow the development of private banks with unlimited liability, which seemed to be essential to support the development of the country (Ögren Reference Ögren and Ögren2010b, p. 10). From the lending perspective, Enskilda banks initially tried to limit their customers to the most reliable kind of borrowers, and possibly to insiders. At the beginning, the deposit activity was minimal but from 1856 they started following the example of savings banks, which had proved capable of collecting and mobilising large amounts of money. They therefore started to pay interest on private deposits (Sandberg Reference Sandberg1979, p. 660).

Sweden was characterised by the presence of a lively peer-to-peer credit market, which sustained the economy long before the establishment of banks. In this context, promissory notes (or IOUs) were one of the most used instruments. They were agreements between private individuals, written notes specifying the terms of a loan that were stipulated without any intermediation (Muldrew Reference Muldrew1998). They represent the traditional form of credit: the money was exchanged within more or less extensive networks that revolved around a series of large capital-holders (usually merchants), who acted as nodal points.

Banking and promissory notes represent the institutional offer and the non-institutionalised or ‘informal’ one respectively. To compare these two contexts and examine the relationship existing between them, and to assess when and how the market started formalising is something that has already been done in several other studies.Footnote 12 What is new here is that I chose to include the variables of gender and marital status, which affect the possibilities and the behaviour of the individuals in the market considerably and therefore further complicate the analysis.

In Uppsala and Gävle, the first banks were founded around the same time, but it seems they developed differently. In fact, the use of bank accounts as a form of saving and investment was more immediate in Gävle, as is proven by two facts: first, the number of banks grew faster and larger there than in Uppsala;Footnote 13 then, as we see in Figure 3, they seem to have gained favour with both small and big savers earlier.

Figure 3. Volume of deposits in banks, age-adjusted sample, Gävle and Uppsala 1810–1910

Sources: see footnote 1.

In Gävle the volume of money deposited in the banks increases considerably after 1850, mostly because of the deposits made by widows; in Uppsala this happens only in the following 20 years and is mainly attributable to married women. In both cities, many spinsters opened bank accounts, but the average amount of their deposits was smaller than that of the other two categories of women. Up to 1870, in both cities almost all deposits were made in savings banks, and it is not by chance that widows and, to a lesser extent, spinsters could be considered as the protagonists of this phase. Between 1890 and 1910, the number of deposits in commercial banks increased consistently, triggering the strong rise in the overall volume of money deposited: this phase, a sort of ‘commercial banks revolution’, sees the incredible growth in the volume of money deposited by married women (thus, couples), even if all the categories analysed here follow the same trend. In Uppsala, many spinsters relied on the services provided by commercial banks starting in 1910s, while in Gävle data suggest that widows were – among unmarried women – the most important account holders in this kind of institution.

In Stockholm, the total number of deposits in commercial banks already surpassed those in savings banks by 1868. The analysis of probate inventories suggests that in Uppsala and Gävle this happened some 30 years later, between 1890 and 1910. Moreover, a study demonstrates that approximately 50 per cent of the adult depositors in the Stockholm's Enskilda Bank, a commercial bank, were women belonging to the middle and upper classes. A very large share of them (70 to 75 per cent) were young, between 16 and 25 years old, and unmarried (Petersson Reference Petersson, Laurence, Maltby and Rutterford2009, p. 259). Again, we notice some differences in the results of this research. In Uppsala, the average age of unmarried women that had a bank account decreases gradually over time: in 1870 they are all over 29 years of age, in 1890 at least over 20, and, for the first time, in 1910 we find spinsters under 20 years old. In Gävle, the age distribution is quite different, and we never find bank account holders under 20 years of age (almost always over 29). Of course, probate inventories are not the best source for studying this issue and, in the future, an analysis of the customers of banks starting from the registers of these institutions could provide us with more complete information.

If we focus on promissory notes (volume, credit), we immediately notice a difference between the two cities (see Figure 4). In Uppsala, IOUs were a tool widely used by all socio-professional categories, something that confirms the existence of a well-developed peer-to-peer credit market; on the other hand, this does not seem to be the case in Gävle. This is a perfect example of how the credit market of two cities could develop in different ways – probably as a consequence of the peculiar characteristics of the local economy – and it also shows which kind of effects this had on the local population, especially on women.

Figure 4. Volume of IOUs (credit), age-adjusted sample, Gävle and Uppsala 1810–1910

Sources: see footnote 1.

The figure given for investment made by spinsters in Gävle in 1890 could be misleading, since it is partly biased by the fact that it comes from a big loan made by one 25-year-old woman. This loan was very likely the consequence of household dynamics, since the debtor was her father: the relevance of this peak should therefore be reduced. In general, the use of IOUs in Gävle is very low, and this is not only true for the categories considered here. The key role of widows as bank account holders in Gävle could be explained by comparing Figures 3 and 4: in fact, we immediately notice that they seemed to be almost excluded from the peer-to-peer credit market. The quick development of banks and the amount of money deposited by widows after 1850 could be the result of an under-development of the informal market, a mismatch between an offer of capital that could not find a demand, at least before the establishment of savings banks.

In Uppsala, married women who lent through IOUs increased over time – except for a slight decline between 1850 and 1870 – and exploded between 1890 and 1910. As we have seen in Figure 3, the volume of bank deposits (especially in commercial banks) also grew significantly in the same period: what is the relationship between these two forms of investment? As I have already stated, in Gävle banks seem to have been the only available alternative, since the peer-to-peer credit was not very developed. By comparison, in Uppsala they seem to be complementary. Widows invested a growing amount of money through promissory notes throughout the nineteenth century. Like married women, widows invested their money by depositing it in banks and, albeit to a smaller extent, by lending it on the private market through promissory notes.

This is a more resolute investment strategy and probably aimed at further increasing revenues. They may have merely inherited these IOUs from their deceased husbands. However, we have previously seen in the inventory of Johanna Carolina Åkerson that the death of the householder did not necessarily correspond with the implementation of more conservative strategies, but rather could result in increased participation in the credit market, as both borrowers and lenders. Not by chance, the low participation of widows in the labour market was usually compensated for by greater activity as lenders in the credit market: in that way widows ensured themselves a regular income that allowed them to survive and possibly accumulate wealth. Moreover, only a minority of these loans was explicitly supplied to a relative (14 per cent in Uppsala and 20 per cent in Gävle), thus indicating that these were not just the result of intra-household dynamics.Footnote 14

Spinsters were perhaps excluded from informal networks, because not even the richest ones participated in them. Maybe they just chose a more conservative approach, as proved by the high number of bank accounts: on average, promissory notes paid 6 per cent on an annual basis, while a bank deposit usually paid 5 per cent but compensated in terms of constancy and security.Footnote 15 Banks were therefore on average a little less profitable, and they probably, over time, became a traditional kind of investment for spinsters. To deposit their money in a bank could represent the surest investment available on the market and this is entirely consistent with the literature on the topic.

On the debt side, the analysis largely confirms what is already stated in the existing literature: unmarried women are not very numerous as borrowers. This is true of both the institutional (bank loans) and the peer-to-peer credit market (IOUs). While spinsters are among the preferred customers of banks when they have money to deposit, there are no bank loans addressed to any of them. No bank loans, but also few IOUs: spinsters really seemed to be excluded from the market as borrowers. On the other hand, from 1870 onwards, there are inventories of widows with bank loans recorded in both Uppsala and Gävle, even though they few in number and limited to the wealthiest among them (as in the case of Mrs Åkerson mentioned above).

Focusing more closely on indebtedness through promissory notes, we immediately notice several differences compared to the credit side. First of all, the volume of transactions that involved spinsters and widows is so low that it is not even possible to compare it with that of married women (and this is already meaningful). In Gävle, the indebtedness of both categories of unmarried women is roughly the same: it reaches a peak in 1890, but in all other years the volume of exchanges falls to zero. It seems likely that the values recorded for 1890 are the result of random operations, and that unmarried women were basically excluded from the peer-to-peer credit market, at least as borrowers. In Uppsala the situation is slightly different: from 1850, widows started borrowing through IOUs as an increasing trend, even though the total volume remains limited.Footnote 16 Once again, there are no operations of this kind that involved a spinster.

It is not easy to explain the absence of unmarried women among the borrowers.Footnote 17 Maybe there was a lack of demand: widows were in many cases in their latter years, when they were more likely to have resources to invest rather than the need for capital. This seems to fit with the life cycle savings pattern highlighted by Morris (Reference Morris2005, pp. 142–70) for English middle-class males. Morris claimed that adult males seek to accumulate the capital they hold by borrowing; then, when they find themselves at a more advanced stage of their lives, they progressively reduce the share of debts in their portfolios. Their participation in the credit market shifts from active (borrowers) to passive (lenders), with investment that privileged safe returns. In this case, widows seemed to behave in a similar way. On the other hand, while many spinsters and widows belonged to the richer categories of society, others may have been considered as riskier borrowers and thus excluded from both the banking and informal offer, which appeared to be specifically addressed to men and married women, basically the same category.

V

The cities of Uppsala and Gävle prove to have had quite different credit markets. They were two results of the same process of formalisation and reorganisation in the context of what has been defined as the Swedish financial revolution. The case of Uppsala testifies that the presence of a well-developed peer-to-peer credit market could delay formalisation through the establishment of banking institutions, which instead find more fertile ground in Gävle, where there was not such a dynamic informal market. Of course, this has several consequences for the behaviour of actors involved, but it does not change the fact that the institutional offer seemed to be best suited for unmarried women. Where peer-to-peer credit was less developed, spinsters and, in particular, widows started to deposit their money in banks earlier, and in a higher proportion (Gävle): this suggests that they probably had some capital at their disposal and were looking for investment possibilities that they could not find on the informal side. On the other hand, where peer-to-peer networks were more developed, unmarried women played a secondary role both as lenders and borrowers, and the overall volume of investments was very limited. In general, it seems that the turn of the twentieth century was a watershed for both widows and spinsters, since between 1890 and 1910 their wealth and the volume of money they exchanged – especially that of bank deposits – increased rapidly and considerably.

There is no doubt that gender and marital status shaped women's economic lives. It would certainly be unwise to consider spinsters and widows as part of a generic group of ‘women alone’ because ‘they share the experience of living without husbands but little else’ (Bennett and Froide Reference Bennett, Froide, Bennett and Froide1999, p. 15). They had different property and inheritance rights, and were regarded differently both socially and morally. However, their status seems to change over the nineteenth century, while society was becoming richer and the credit market becoming more and more formal and impersonalised.

Widows were in a specific phase of their life cycle and this also had an effect on the strategies they implemented to lend and borrow. The comparison between the inventories of Johanna Carolina and his husband, Lars Vilhelm Åkerson, suggested that widows did not always prefer a more conservative approach. In fact, in the course of the 17 years following the death of the householder the family business underwent a dramatic change, towards a higher indebtedness aimed at financing the investment in stocks and in direct lending (also through promissory notes). Although widows were numerous among bank account holders, some of them were also active in the peer-to-peer market and lent through promissory notes: they seemed to be better inserted into informal networks than spinsters. On the other hand, never-married women appear as borrowers in the peer-to-peer credit market only rarely, probably when the banking offer was limited or reserved for other categories, as seems to have been the case in Gävle from the 1890s onwards.

To conclude, this study demonstrates that, as expected, probate inventories have many problems related to their representativity compared to the living population. However, they have been very useful for observing individuals’ investment strategies from a different and interesting perspective. The gender perspective further complicates the analysis and, even if probates are rich in information, when women's economic behaviour is assessed it seems that it is not possible to get a comprehensive picture of the situation. It is like a complicated puzzle, where you just have to find as many pieces as you can in an attempt to work out what the complete picture looks like.