No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

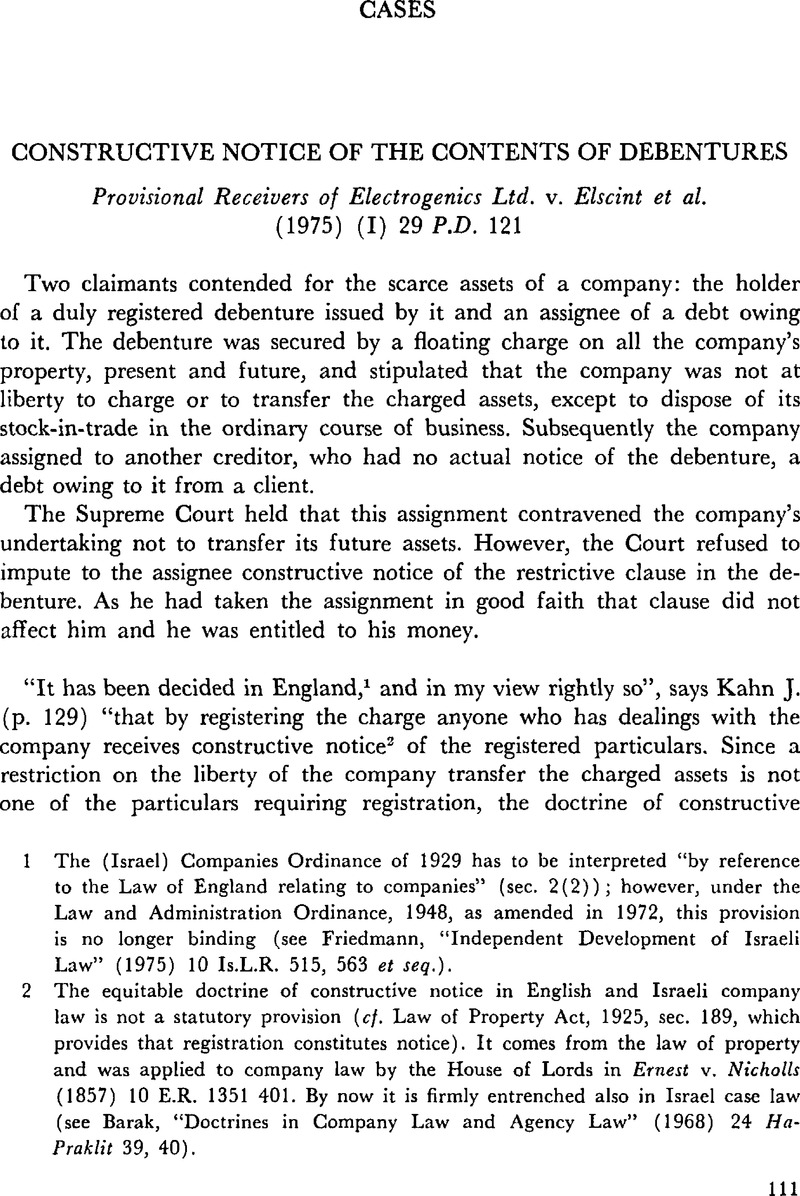

Constructive Notice of the Contents of Debentures

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 12 February 2016

Abstract

- Type

- Cases

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Cambridge University Press and The Faculty of Law, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem 1976

References

1 The (Israel) Companies Ordinance of 1929 has to be interpreted “by reference to the Law of England relating to companies” (sec. 2(2)); however, under the Law and Administration Ordinance, 1948, as amended in 1972, this provision is no longer binding (see Friedmann, , “Independent Development of Israeli Law” (1975) 10 Is.L.R. 515, 563Google Scholaret seq.).

2 The equitable doctrine of constructive notice in English and Israeli company law is not a statutory provision (cf. Law of Property Act, 1925, sec. 189, which provides that registration constitutes notice). It comes from the law of property and was applied to company law by the House of Lords in Ernest v. Nicholls (1857) 10 E.R. 1351 401. By now it is firmly entrenched also in Israel case law (see Barak, , “Doctrines in Company Law and Agency Law” (1968) 24 Ha-Praklit 39, 40Google Scholar).

3 See infra.

4 Gower, , Modern Company Law (3rd ed., 1969) 422–3Google Scholar; Palmer, , Company Law (21st ed., 1968) 242, 400Google Scholar; Buckley, , Companies Acts (13th ed., 1957) 228.Google Scholar These three are cited by Kahn J. at p. 131 in the case under review (also referred to infra as the Elscint case).

5 The value of debentures (excluding Government bonds) listed on the Tel Aviv Stock Exchange was at 31.12.1974 IL 13.9 billion, compared with a value of listed shares of IL 3.7 billion (T.A. Stock Exchange Annual Summary, 1974). Many debentures issued in series and all those issued singly are not so listed.

6 Companies Ordinance, sec. 220A; cf. Companies Act, 1948, sec. 319 (which does not include rent for houses and land leased by the company among the preferential debts).

7 Most recently by the National Insurance (16th Amendment) Law (1975) S.H. no. 764, p. 102.

8 E.g. in Mediterranean Car Agency v. Gav Yam Co. (1969) (II) 23 P.D. 276.

9 In Bank Leumi le-Israel v. Israel British Bank (1972) (II) 26 P.D. 468, per Sussmann J. at p. 477, the Court held, on the authority of Wilson v. Kelland [1910] 2 Ch. 306, that when a company borrows to buy real property and a mortgage on that property is given as security, the lender also acquires an equitable charge. This charge will rank before other, earlier, equitable rights: those of debenture holders under a floating charge which restricted the company's liberty to create charges in priority to or pari passu with it. Sussmann J. contended that where a company used loan capital to finance a purchase, equity does not regard it—to the extent of the loan—as the owner of the purchased property. As a floating charge attaches only to the assets of the company, a mortgage on such of its assets which do not form part of that property, ranks before the floating charge. In another recent case, Receivers of Hermann Hottander Investment Co. v. Israel Industrial Bank (1974) (II) 28 P.D. 68, the articles of the respondent bank provided that the bank had a lien on its shares, fully-paid or not, for all moneys owing to the bank by the owner of the shares. Kahn J. ruled that this was an equitable lien and that it did not require registration by the investment company which had purchased the shares (fully-paid up). The proceeds from the sale of those shares had first to be applied, according to Kahn J., so as to satisfy the bank's claims against the insolvent company before the claims of other creditors could be met. Here none of the other creditors was secured but it appears from the decision that had there been a secured creditor the decision would not have gone the other way. As to the preference given to a lawyer's lien over the claims of debenture-holders under a floating charge, see Brunton v. Electrical Engineering Co. [1892] 1 Ch. 434.

10 [1892] 2 Q.B. 700 (CA.).

11 It may be noted in passing that the interest charged in 1891 on an advance of money for three months against ostensibly sound collateral (an assignment of a certified sum due to the assignor from an insurance company) was at the rate of 20% p.a.

12 Today, secs. 103 and 105 of the Companies Act, 1948 and sees. 127(12) and 125(3) of the Companies Ordinance. Sec. 43 of the Companies Act of 1862 did already institute a register of mortgages and charges to be kept—open to inspection—at the registered office of the company, recording particulars of the mortgaged or charged property, the amount of the charge and the name of the mortgagee—today sec. 104 of the Companies Act, 1948, and sec. 125(1) of the Companies Ordinance.

13 Today, Companies Act, 1948, sec. 95 and Companies Ordinance, sec. 127(1).

14 Story on Equity (3rd English ed., 1920) 163, relying on Hall v. Smith (1807) 14 Ves. Jun. 426, 439; 33 E.R. 584, 587, per Sir W. Grant, M.R.: “If the circumstance that the land was in lease had been concealed, that would be a different consideration. But… if the party has notice that the estate is in lease, he has notice of everything contained in the leases; e.g., if there is a covenant to renew, the purchaser cannot object that he had not had notice of that particular covenant.”

Cf. the proviso to sec. 4(3) of the Security Interests Law, 1967: “A pledge shall be effective against other creditors of the debtor… (3) in the case of movable property and securities… upon registration of the pledge… Provided that against a creditor who knew or should have known of the pledge it shall be effective even without registration”. Prof.Weisman, J. in his Commentary on the Security Interests Law, 1967 (Jerusalem, 1974, in Hebrew) 146Google Scholar, suggests that “the notice required is not, it would seem, of the particulars of the pledge. Knowledge of the actual existence of the pledge imposes a duty to investigate its particulars. Where a third party fails to do so he is deemed to be one ‘who shall have known’ those particulars which could be ascertained by proper enquiry.” On this Law (called there the Pledges Law) see id. (1969) 4 Is.L.R. 417.

15 [1892] 2 Q.B. 700, 708.

16 These words of Lord Esher are quoted with approval by Berinson, J. in Rosenstreich v. Israel Automobile Co. (1973) (II) 27 P.D. 709, 712Google Scholar (see a digest of this case in (1975) 10 Is.L.R. 144). But recent Israeli legislation appears to tend to approve of, and even extend, the concept of constructive notice. E.g., sec. 18 of the Law of Agency, 1965, states: “Knowledge. For the purposes of this Law, a person shall be deemed to have knowledge of a matter if he should as a reasonable man have knowledge thereof or if he has received notice thereof in the ordinary way.” In his Commentary on the Law of Agency, 1965 (Jerusalem, 1975, in Hebrew) 584, Prof. A. Barak refers to the phrase “if he should as a reasonable man have knowledge thereof”, which in his view is open to several interpretations. “One might say that it is limited to those cases where a person has the means to know but does not draw the conclusion that a reasonable man would have drawn in his place. One might say on the other hand that it is limited to those cases where a person does not know and has not got the means to know but is under a duty to acquire the means and to know. In our opinion the above phrase in the Law of Agency should be given a wide interpretation, so as to comprise both meanings. There are several reasons for this: in the first place from a literal point of view, it is a reasonable interpretation and is in accord with the interpretation of this phrase in other Statutes. Secondly, from the point of view of the legal effect—namely the imposition of the legal norm on a person who does not know but has the means to know and is under a duty to know—this is a reasonable one within the framework of the Law of Agency.” See also supra, n. 14, on sec. 4(3) of the Security Interests Law, 1967.

17 The fact that the assignor misled the assignee does not seem to have influenced the judgment: Lord Esher remarked, obiter (p. 712), “I have a strong opinion that even if the false statement that the debentures did not affect the plaintiff's title to the mortgage had never been made, the doctrine of constructive notice would not have applied. It is not, however, necessary to decide this question now”. This is cited, evidently with approval, by Kahn J. (p. 130).

18 [1903] 2 Ch. 654.

19 [1892] 2 Q.B. 700. See supra text at n. 10.

20 See supra n. 12.

21 Today part of sec. 95(1) of the Act and of sec. 127 (1) of the Ordinance.

22 Sec. 98(1) of the Act of 1948 and sec. 127 (5) of the Companies Ordinance.

23 The Act of 1862 had already provided (in sec. 174(5)) that every person may inspect the documents kept by the Registrar (now sec. 426(1) of the Act of 1948 and sec. 243(3) of the Ordinance).

24 Now sec. 95 of the Act and sec. 127 (1) of the Ordinance.

25 Secs. 125–127; sees. 129–133.

26 Secs. 95–106.

27 (1906) 95 L.T. 829.

28 According to counsel; ibid., at p. 832.

29 Ibid., at p. 834.

30 [1903] 2 Ch. 654; see supra n. 18.

31 [1910] 2 Ch. 306; see also supra n. 9.

32 “[T]he particulars registered…amounted to constructive notice of a charge affecting the property but not of any special provisions contained in that charge restricting the company from dealing with their property” (p. 313) relying on the judgment of Kekewich J. in the Standard Rotary Machine case (supra n. 29).

33 Re Standard Rotary Machine Co. (1906) 95 L.T. 829, 834.

34 Brunton v. Electrical Engineering Co. [1892] 1 Ch. 434. Counsel did not do justice to his cause and had apparently not read the Brunton case. There Kekewich, J. referred to Wheatley v. Silkstone & Highmoor Coal Co. (1885) 29 Ch. D. 715Google Scholar (which had given priority to a subsequent mortgage over a floating charge), and remarked (p. 440) that the result of that decision “being, it appears, that a special form [of debentures] has been invented to meet the difficulties which that decision gave rise to”, namely to stipulate in the debenture that no charge having priority to the debenture may be created. This seems, then, to have been the practice for over 20 years before the decision in the Standard Rotary Machine case (and not 14 years, as counsel submitted).

35 (9th ed., 1906) vol. 3, p. 239.

36 Nor, it seems, did he remember his own judgment in the Brunton case (see supra n. 34).

37 K.T. no. 159, p. 731; amended after the judgment—K.T. no. 3289, p. 810 (see infra, n. 59).

38 Sec. 127(5); see supra n. 22.

39 Companies Ordinance, sec. 125(3); see supra n. 12.

40 So that the security shall not be void against the creditors of the company—sec. 127(1) of the Ordinance; see supra n. 21.

41 Gower, , Company Law (3rd ed., 1969) 430.Google ScholarBankes, L.J. thought in National Provincial & Union Bank of England v. Charnley [1924] 1 K.B. 431, 444Google Scholar (C.A.) “that the object of the legislature in requiring delivery to the Registrar of the instrument as well as the particulars is to enable him to form an independent judgment in reference to what he ought to put on the register.”

42 Sec. 103 of the Companies Act, 1948. That an examination of the instrument itself seems to be common practice may be inferred from Re Mechanizations (Eaglescliffe) Ltd. [1966] Ch. 20, per Buckley J. (p. 35): “In order to discover the terms and effect of the charge…one must look at the document creating the charge and not at the register.” Cf. Re Eric Holmes (Property) [1965] Ch. 1052.

43 It was included in the original (Palestinian) enactment of 1929.

44 Thus non-compliance with sec. 127(1) and the failure to deliver for registration the instrument creating the charge “merely” invalidates the security against the liquidator and other creditors; the duty to forward the copy under sec. 128 is absolute. This duty evolves on the company; the registration under sec. 127 may be effected by any interested person (subsec. 10; cf. sec. 96(1) of the Act).

45 Fellman, , Company Law in Israel (Tel Aviv, 1960, in Hebrew) 526.Google Scholar

46 See infra nn. 50, 51.

47 Receivers of Hollander Investment Co. v. Israel Industrial Bank (1974) (II) 28 P.D. 66, 78; see also supra n. 9.

48 This part of Kahn J.'s judgment was—it is submitted—given per incuriam: the Articles of Company X may include the (uncommon) provision that also fully-paid shares are subject to a lien for the member's liabilities to the company. Company Y purchases some of these shares. No holder of debentures issued by Company Y—and it was that kind of creditor envisaged by Kahn J. (see supra n. 9)—need know that some of Y's assets are subject to that lien: the company's balance-sheet would not normally show a detailed list of the shares in which the company had invested; even if it did, that particular investment might have been made after the date of the last balance-sheet. Moreover, the balance-sheet of a private company is still, in Israel, not a public document (sec. 36(5) of the Ordinance; but cf. Companies Act 1967, sec. 2.) Since the creditor cannot know that Y's assets include shares of X, no notice of the lien of X on those shares should be imputed to him. Seeing that such liens are normally created on partly-paid shares only—cf. art. 8 of the Israeli and art. 11 of the English Table A—had Kahn J. applied to this case the criteria as to constructive notice formulated by Lord Esher, M. R., in the English & Scottish case—see supra text after n. 17—on which Kahn J. later based his judgment in the Elscint case, he should have held that the Articles of a company “do not necessarily affect” the title to such shares of persons purchasing in good faith fully-paid shares of that company, and that such persons should therefore not be fixed with notice of the lien.

49 In Credit Bank v. Receiver of D.T.P. Co. (1968) (II) 22 P.D. 529, 532, the issue was, which were the assets included in a specific charge. Witkon J. held that, “the criterion is—will a person who comes to examine [the debenture] at the Registrar of Companies be able to elicit, by perusing it, what assets are subject to the charge?” That case did not evolve on the question of notice; had it done so, it might have been authority for the proposition that, by filing a debenture at the Registrar's, constructive notice is given also of the particulars contained therein.

50 In the normal form of debentures set out in Palmer's, Company Law (London, 21st ed., 1968) 368Google Scholaret seq., such a clause is given as the first of the “usual” conditions (at p. 372). Palmer's editors go on to say (ibid.) that “in many modern instances the prohibition to create prior or equal charges is not absolute…”

51 The Securities Regulations (Particulars of the Prospectus, its Structure and Form), 1969 (K.T. no. 2417, p. 1794) require (in r. 32(5)) that where debentures are offered to the public, the prospectus must set forth whether, and the extent to which, the issuer has restricted his right to create further charges on his assets. It is submitted that this provision is an indication that such a restriction is likely to be included in the charge. This writer has gone through several hundred different debentures issued by Israeli companies; only in one was there no such qualified or unqualified restriction.

52 See Brunton v. Electrical Engineering Co. [1892] 1 Ch. 434, per Kekewich J. at p. 440; quoted supra n. 34.

53 [1892] 2 Q.B. 700; see supra n. 10.

54 Companies Act, 1900, sec. 14(9); see supra text at n. 20.

55 [1903] 2 Ch. 654; see supra n. 18.

56 (1906) 95 L.T. 829; see supra n. 27.

57 [1910] 2 Ch. 306; see supra n. 31.

58 The fact that the Amendment—the first since 1951—deals only with this point strengthens the assumption that its purpose was to redress the effect of the decision in the Elscint case. The Order might have amended also Particular 4: “Special conditions which might change the amount secured, such as a stipulation to make payment in gold (sic) or in foreign exchange”. The Order does still thus not include a reference to a possible linkage of capital (and interest) to the cost-of-living index which, since the late fifties, has been very common in medium and long-term loans.

59 K.T. no. 3289, p. 810.

60 K.T. no. 159, p. 731.

61 Cf. the provisions regarding the registration of charges in Scotland (but not in in England), enacted by the Companies (Floating Charges) (Scotland) Act, 1961, and incorporated in the Companies Act, 1948. Under sec. 106A (7) (e), a floating charge securing a series of debentures (in the Elscint case a single debenture had been issued), a statement on the restrictions, if any, on the power of the company to grant further securities (but not, apparently to transfer its assets), ranking in priority to or part passu with, the floating charge, is one of the particulars which have to be delivered to the Registrar.

62 See supra nn. 14 and 16.