Introduction

Pragmatic trials aim to generate timely evidence for translation through conduct in real-world settings [Reference Treweek and Zwarenstein1]. While balancing research rigor and speed, researchers conducting pragmatic trials must also ensure that procedures are feasible, minimize practice burden, and maintain real-world conditions [Reference Loudon, Treweek, Sullivan, Donnan, Thorpe and Zwarenstein2]. This is critical for bolstering trial acceptability in the practice setting and increasing the likelihood that the intervention is implemented and evaluated in a manner consistent with routine care delivery.

Involvement of patients and clinicians in the design of interventions is one strategy for increasing their acceptability and feasibility [Reference Lyon and Koerner3–Reference Bayliss, Shetterly and Drace5]. Similarly, engagement of potential users in adapting existing evidence-based practices for new settings and assessing barriers to implementation of new practices are increasingly common approaches to improving intervention fit and building relationships with users [Reference Stetler, Legro and Wallace6–Reference Yousefi Nooraie, Shelton, Fiscella, Kwan and McMahon8]. Formative evaluation methods, e.g., surveys, interviews, and observations, are commonly employed to understand user needs and implementation context [Reference Stetler, Legro and Wallace6,Reference Rogers, De Brun and McAuliffe9], including in primary care and hospital settings [Reference Rogers, De Brun and McAuliffe9]. However, while formative evaluation has been conducted in hospital and emergency department (ED) settings [Reference Rogers, De Brun and McAuliffe9–Reference Piotrowski, Meyer and Burkholder11], there are few examples of how these methods can be rapidly deployed in busy clinical settings [Reference Bayliss, Shetterly and Drace5] before, rather than after, implementation begins. Qualitative research, in particular, can provide key insights related to individual (e.g., knowledge and attitudes) and organizational (e.g., workflow, billing) factors that will impact implementation success. These methods typically require considerable time and effort, though, which is a challenge for pragmatic trials that hope to generate evidence for clinical practice decision-making with little delay for preimplementation assessments.

Rapid research methods, including qualitative methods, have been a hallmark of evaluations that require timely feedback to decision-makers [Reference McNall and Foster-Fishman12–Reference Vindrola-Padros14]. They have also emerged as important tools in process evaluation and implementation science approaches [Reference Hamilton and Finley15], with emphasis on how to speed qualitative data collection and analysis without compromising quality, including methods that leverage theories or frameworks to derive a priori categories for analysis [Reference Gale, Wu and Erhardt16–Reference Nevedal, Reardon and Opra Widerquist18]. Additional work is needed to understand how best to conduct rapid qualitative appraisal in a busy clinical setting and how to use these methods in the preimplementation period of pragmatic trials, especially when study and intervention procedures need to be quickly integrated into practice.

This study was conducted in the preimplementation period of a pragmatic point-of-care trial, assessing effectiveness and implementation of a community paramedic (CP) program to shorten or prevent ED visits and hospitalizations in adults being treated in the prehospital (home, clinic), ED, and hospital settings. The aim of this qualitative inquiry was to identify issues related to successful implementation of both the program and the trial, including existing workflows that may require action to ensure feasible program and study conduct. Furthermore, by engaging individuals likely to be involved in or impacted by the trial or the intervention, the study team aimed to develop relationships that would lead to patient referrals to the trial and develop opportunities for ongoing feedback and refinement as needed.

Materials and Methods

This study took place at Mayo Clinic Rochester (Rochester, MN, USA) and Mayo Clinic Health System in Northwest Wisconsin (community hospitals and practices spanning the region between Eau Claire and Barron, WI, USA). CPs are paramedics with specialized training in chronic disease management and the social determinants of health [Reference Chan, Griffith, Costa, Leyenaar and Agarwal19]. Since 2016, CPs in the Mayo Clinic Ambulance Service have provided care in community and home settings for a range of chronic conditions [Reference Juntunen, Liedl and Carlson20,Reference Stickler, Carlson and Myers21]. The Care Anywhere with Community Paramedics (CACP) program was developed to extend care in the ambulatory setting (e.g. private residence, hotel, shelter) for patients with intermediate acuity health needs. These patients are often hospitalized because necessary interventions and services are not available in the home (e.g., clinical evaluation/triage for acute conditions, intravenous medication administration) or are not available in the home in the desired timeframe (e.g., wound care, medication management assistance, delivery of self-management education). The parent point-of-care pragmatic trial is a two-group 1:1 randomized trial of CACP versus usual care on effectiveness outcomes, including days spent alive at home at 30 days. Eligible patients were those 18 years or older and within approximately 40 miles of Rochester, MN, or in the geographic area spanning Eau Claire to Barron, WI. The trial also includes an assessment of implementation outcomes, e.g., program reach.

Developed and initially funded as a 15-month trial, the timeline included 4 months for study startup and pre-implementation assessment (i.e., rapid qualitative evaluation), the results of which are presented here. The primary method of this preimplementation assessment was interviews with individuals identified as being in roles expected to interact with or be impacted by the CACP program. Individuals were invited by email to participate. Snowball sampling was used to identify additional individuals for interviews. Interviews were conducted via video conference and recorded for analysis. The interview guide was developed by team members with expertise in implementation science and reviewed by clinical team members. It was informed by constructs in the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research [Reference Damschroder, Reardon, Widerquist and Lowery22], including perceptions of the intervention (e.g., evidence base, relative advantage), compatibility with existing workflows, perceptions of patient needs, and priorities and preferences of those who may be impacted by the intervention (See Appendix A). Prior to each interview, the study team prepared by reviewing the role of the participant and discussing potential additional question probes for unique anticipated insights of that role. The principal investigator also presented the program to institutional committees and care teams (i.e., “roadshows”) and solicited questions and concerns from attendees. Those were summarized in debriefing notes and shared with the study team, serving as a secondary source of preimplementation assessment data.

The data analysis procedures are portrayed in Fig. 1. The analysis approach was based on a system developed by the RREAL Rapid Research Evaluation and Appraisal Lab© [23] that uses table-style RREAL RAP (Rapid Assessment Procedures) Sheets to summarize qualitative content (e.g., from interviews), facilitate cross-case analysis and team reflection, and provide a format for rapid dissemination to decision makers. It is similar to other matrix-based approaches to data summarization [Reference Gale, Wu and Erhardt16–Reference Nevedal, Reardon and Opra Widerquist18] and qualitative framework analysis [Reference Gale, Wu and Erhardt16], but it differs in the iterative and team-based nature of data collection and analysis. For this study, after each interview, one member of the study team summarized the key content in a template with rows for each construct in the interview guide. A second team member who participated in interviews reviewed the summary and provided additional feedback. Time stamps for key examples of content were noted in the table to facilitate the identification of exemplar quotations for research dissemination.

Fig. 1. Data collection and analysis procedures. Data collection and analysis was iterative. Data sources included interviews and discussions with key clinical and administrative groups. Rapid qualitative analysis methods and team reflections informed changes to presentations and were used to identify areas for improvement.

Interviews and roadshows took place concurrently during the preimplementation period, and data collection and analysis were iterative, with interview findings informing additional roadshow presentations. Results from interview analysis were reviewed along with notes from roadshow presentations at biweekly study team meetings. The team refined their roadshow presentations and made changes to the program and study procedures to be responsive to requests for additional information, newly identified concerns, and potential barriers to implementation. They communicated these back to interview participants and care teams or institutional committees as appropriate to demonstrate commitment to responsiveness in trial and intervention deployment. This study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board (IRB #21-010816).

Results

Thirty individuals participated in interviews between December 2021 and April 2022. Participant characteristics are shown in Table 1. All interviews were individual except one, which was dyadic. Mean interview duration was 31 minutes (range 19, 59).

Table 1. Characteristics of interview participants

* Indicates primary role; some individuals had more than one potential role, e.g., referring provider and administrative leadership roles.

** Indicates a centralized service for locations in both MN and WI.

The study principal investigator gave “roadshow” presentations to 17 institutional committees and clinical departments. Written information about the program was disseminated to practice leaders in participating clinical and geographic areas. Presentations were conducted using video conferencing software and averaged 15 to 20 minutes in duration (10 minutes of presentation and 5 to 10 minutes for questions and answers). Attendance ranged from approximately 10 to 50, based on the size of the department or committee. Most clinical meetings were multidisciplinary and included all members of the care team, e.g., physicians, advanced practice providers, nurses, and desk staff.

Analyses identified barriers to implementation, including low awareness of the program and CP scope of practice. Concerns included potential disruption in staffing for other programs using CP services, possible program misuse (i.e., underutilizing CPs scope of practice, referring patients who are inappropriate for the CACP program or who would be better served by other home health, long-term care, or ambulatory care services), and general safety concerns for providers being sent into a patient’s home were also noted. Participants also stressed the need for constant and effective communication, especially given the large number of people involved in care for patients such as these (i.e., patients with multiple chronic conditions, intermediate care needs, and frequent hospital of ED use). Solutions included the development of program materials on the CP scope of practice, clearly defined patient eligibility criteria and referral processes, safety protocols for CPs working alone in the home environment, guidelines for communication between CPs and other clinical teams, and a CACP quality assurance review process.

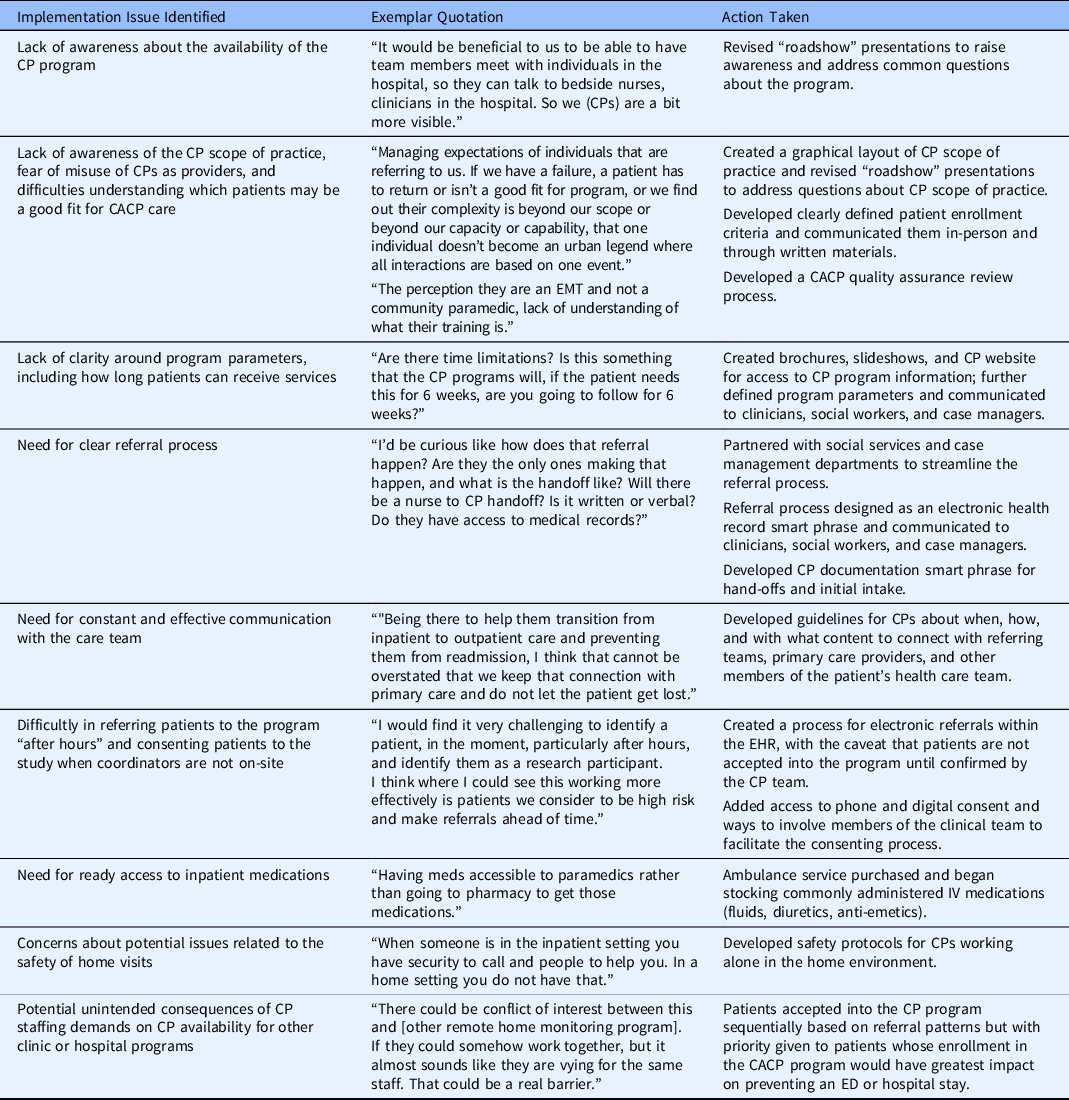

Most concerns, including those about workflows, were addressed prior to the start of trial enrollment. Most notably, the patient referral process was amended to allow for referrals to be done within the electronic health record (EHR) to lessen the administrative burden for providers. The team also developed EHR smart phrases to guide referral documentation and ensure that CPs have the information they need to safely and effectively care for referred patients, as well as CP note templates for the most prevalent clinical encounter types. Examples of issues identified in the preimplementation period, which could impact successful implementation, are listed, along with exemplar quotes from interviews and actions taken, in Table 2.

Table 2. Examples of preimplementation issues identified, exemplar quotes from interviews, and actions taken

CACP = Care Anywhere with Community Paramedics; CP = Community Paramedic; ED = Emergency Department; EHR = Electronic Health Record; EMT = Emergency Medical Technician.

Discussion

There is growing interest in pragmatic and point-of-care clinical trials, especially their ability to generate timely and relevant evidence in heterogenous real-world settings and with diverse populations. However, trials conducted within the clinical practice also have the potential to disrupt practice and compete for scarce clinical resources; in doing so, study teams may risk frustrating clinical partners, thwarting the successful execution of the trial and ultimately impeding the pragmatic and point-of-care aspirations of these studies. Early engagement of practice stakeholders can inform adaptation of trial activities to minimize their impact on the practice, but engaging clinicians and others who work in busy settings like hospitals and EDs and rapidly using data to inform decisions require new approaches to data collection and analysis.

Pragmatic trials increasingly deploy qualitative methods to understand implementation context, but there is limited guidance on how to collect and analyze data quickly enough to be actionable before enrollment commences. This study used rapid procedures that leveraged audio recordings (rather than transcription), systematic analysis by two members of the study team using a template with constructs related to implementation determinants, notes from presentations and discussion with a large number of clinical teams, and study team biweekly reflections to identify important issues and address them when possible. This approach is similar to others that use templates in analysis or that leverage implementation frameworks or other models to guide deductive analysis [Reference Gale, Wu and Erhardt16], although this study also included presentation notes and reflective discussions in the analysis procedures. Review of audio files and inclusion of timestamps to identify quotes represents an adaptation of some rapid approaches that use audio files [Reference Neal, Neal, VanDyke and Kornbluh17] and allows the study team to review segments in identified categories and by role (from the template) if questions about individual or group input arose during team reflections. They also supported findings for peer-reviewed dissemination such as this.

In addition to providing a framework for analysis, this approach also served to create lines of communication with clinical teams, garner front-line clinical staff and leadership support for the trial intervention, and ultimately support participant enrollment and trial procedures. Biweekly team reflections were an opportunity for team members involved in interviews and those involved in roadshow presentations to triangulate input from both data sources and discuss potential actions. The principal investigator was then able to report back to key informants the systematic approach to reviewing and acting on their recommendations, along with a request to use personal contact (e.g., an email to the principal investigator) for any other future recommendations for consideration.

While this approach was instrumental to the successful launch and conduct of the CACP pragmatic trial, it has limitations. Although potentially less-resource intensive than some traditional qualitative methods, the rapid approach has required significant staff resources during a concentrated period of time. Analyst and study coordinator effort to create research documents, recruit and enroll participants for interviews, and conduct and analyze interviews was significant. Analyst effort for data collection and analysis was approximately 200 hours (0.20 FTE) during those months. This estimate adds to a growing literature on the benefits and demands of rapid qualitative analysis, previous reports of which have compared hours or days to complete rapid analysis versus transcript coding [Reference Gale, Wu and Erhardt16] or that estimated analysis time relative to the length of an interview audio recording [Reference Neal, Neal, VanDyke and Kornbluh17]. Rapid work such as this often requires a team of several individuals that can collectively commit to high effort in a short timeframe so that there is dedicated time for collecting and analyzing larger numbers of interviews or group discussions in weeks or a few months rather than over several months or a year. The principal investigator also presented to 17 groups, documented the discussions, and was responsible for identifying and implementing solutions for issues raised by participants. Some of these changes were complex and required various workflow changes and institutional approvals. When solutions were not available, the study team needed to follow-up and communicate that with participants. Furthermore, although this work identified and addressed critical issues before enrollment launched and in doing so increased trial feasibility, there were challenges to engaging busy care teams in the research. These challenges were magnified by institutional restrictions on engaging care team members in certain types of research as a way of minimizing clinician burden during the COVID-19 pandemic. There were also limitations to identifying which clinicians were engaged during roadshow presentations, as attendees were largely participating via video conference. Limitations related to individual consent meant the team was unable to record presentations, so analysis relied on notetaking. Therefore, the ability to determine how effective the roadshows were at fostering trial referrals will be limited to a care team level of evaluation. Future research could investigate methods to assess participation or engagement at the individual level.

Likewise, there are limitations related to the exclusion of patient input in this preimplementation period. Members of this study team collected patient feedback during an earlier study of CP care for patients with diabetes, and those data informed the current trial intervention [Reference Juntunen, Liedl and Carlson20]. Surveys, as well as interviews with patients who received care in the CACP program, are planned for the implementation and postimplementation periods of this trial. Finally, there were some issues that did not emerge in this preimplementation assessment and were identified after enrollment began, including outpatient pharmacy regulations that precluded the dispensation of intravenous medications to the ambulatory setting. This demonstrates that critical need for ongoing trial feedback in addition to preimplementation assessment.

In conclusion, in the months prior to starting trial enrollment and intervention, this study team was able to identify and resolve key areas of concern that would have posed significant barriers to study completion. While resource intensive in the short term, actions taken as the result of preimplementation assessment were directly related to trial acceptability and feasibility. The rapid approach, which was uniquely deployed in the months prior to a pragmatic, point-of-care trial in a busy clinical practice setting, was well-suited to meet the preimplementation study objectives in a rapid but systematic way. This approach also served to foster relationships and develop open communication and feedback loops with clinical and administrative partners who would go on to refer patients to the trial or otherwise interact with the CACP program in practice.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/cts.2023.18

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Michael Juntunen and Chad Liedl of the Mayo Clinic Ambulance Service and Nicholas Breutzman of the Mayo Clinic Robert D. and Patricia E. Kern Center for the Science of Health Care Delivery for their support of this project. This study was funded by Mayo Clinic Clinical Trials Award Funding and supported by Grant Number UL1 TR002377 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) (JLR, RGM, EOWG) and the Mayo Clinic Robert D. and Patricia E. Kern Center for the Science of Health Care Delivery (JLR, RGM, OAS, MAL, EOWG, JJM). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Disclosures

In the last 36 months, Dr McCoy has received support from NIDDK, PCORI, and AARP®. She also serves as a consultant to Emmi® (Wolters Kluwer) on developing patient education materials related to prediabetes and diabetes. All other authors declare no conflicts.