Since the end of the nineteenth century, the Alzate family grasped the magnetism of the Natural Man and its economic potential and orchestrated a family craft business of fake pre-Columbian pottery. It all began when the mestizo family from Antioquia, who had previously been dedicated to taxidermy, guaquería (the desecration of pre-Hispanic burials in search of gold and pottery), and trade, realized the gulf between the value of contemporary pottery and that of pieces created by pre-Hispanic indigenous people during a visit by Swiss naturalists. That epiphanic moment was followed by their idea to manufacture pieces for the international market, aging them and passing them off as antiques, along with the occasional original ones, which would soon disappear.

In this article, I explain how the Alzates made replicas aesthetically and narratively verisimilar to the expert eye. They created pieces that would dialogue with collectors’, anthropologists’, museums’, and tourists’ desires and imaginaries, as well as authenticity criteria, about indigenous pre-Columbian peoples. These expert and amateur imaginaries were related to multiple discourses and images that had nurtured conceptions about pre-Hispanic peoples since the late fifteenth century. In their pottery, the Alzates engaged in an aesthetic dialogue with those discourses and images so that even connoisseurs could experience the nostalgia of a pre-Columbian lost and blurred past. Thus, they not only had to replicate the styles, symbolisms, traces of decay and disintegration but also had to mimic the ways the guacas (buried pre-Columbian spiritual and material treasures) were found and unearthed, creating a theater of discovery. And for that theater of discovery of ancient civilizations, the mythical idea of the Natural Man, which Columbus imposed on indigenous peoples, was key. There was no discovery without something that was occluded for centuries or unknown for Europe (or Creoles), without a sense of adventure and risk, and without the meeting of a civilization radically divergent from theirs. This is precisely why I show the relationship between these forgeries’ process of production, circulation, and consumption and the ways Latin American indigenous peoples have been conceived by others.

When these pieces were considered authentic, they nurtured the myth of the pre-Columbian Natural Man and, together with other forgeries, nourished and transformed what was considered authentic pre-Columbian pottery. By mocking imaginaries around indigeneities, such fakes operate politically by undermining social hierarchies linked to essentialized identity and race. Fakes attack these essentializations that are erected on “material evidence” such as archaeological art or artifacts, bones, ruins, and their pastness lookalike. This research stresses how “authentic fakes,” together with official and popular discourses, certain exhibition and validation rhetorics, and other mises-en-scène construct what is sacralized as uncontaminated, original, and traditional.

The Alzate history epitomizes a myth in Barthes’s terms, in this case, the myth of the Natural Man. For Barthes ([1958] Reference Barthes1999), a myth is a widely accepted idea that is neither true nor false. It has strong emotional anchors and a repertoire of associated representations. Behind the myth, there are always certain abstract concepts, but they cannot operate without the representations that cocreate and convey them. Myths have effects on how we bond, what we can see, and how we understand reality. Precisely, their magnetism consists in the fact that they pass themselves off as unmediated reality. That is, they appear politically neutral, objective, ahistorical, and universally valid—in other words, natural. Not just anyone can give rise to a myth. Myths typically solidify through popular channels of communication that are managed by the dominant classes. Even so, not all myths are politically conservative; in fact, some of them are sustained through subversive means, and there are myths that can be used for politically opposite purposes. Even contradictory myths coexist. The problem is that they distort the way reality is interpreted, hide individual agencies, obscure the historicity of certain phenomena, and are able to pass off as natural.

The seductiveness of the myth of the Natural Man has an expanding negative influence for indigenous peoples. This is problematic because we find ourselves in Latin America with identity policies that artificialize what is cataloged as “indigenous” in a musealized way and purport the autonomy of indigenous people (Buege Reference Buege1996; Gros Reference Gros2000; Wade Reference Wade and Cheater1999; Hale Reference Hale2002, [2004] Reference Hale2016; Ramos Reference Ramos2004; Jackson and Ramírez Reference Jackson and Clemencia Ramírez2009).

The representations that give life to the myth of the Natural Man lead to ramifications such as alliances between the “permitted Indian” and neoliberalism to give no space to alternative system models (a term that Hale [Reference Hale2002] borrowed from Cusicanqui [(2004) 2016]; see also Balán [Reference Balán2023] on an earlier version of this brief state of affairs). It is also common for rights to be taken away and for treaties with indigenous peoples to be broken because of changes to traditional ways of hunting, fishing, or farming (Buege Reference Buege1996). Additionally, eco- and ethno-tourism are typically designed to comply with state development models and give no or minimum earnings to the communities involved (Jackson and Ramírez Reference Jackson and Clemencia Ramírez2009; Del Cairo Reference Del Cairo2011); an expanding market of eco-friendly products gives only decorative solutions while hiding structural ecological toxicities; bioprospecting feeds on indigenous knowledge but excludes the indigenous people from its patents; and even “environmental services” that derive pollution and waste from North to South—all these are protected under the ideology of sustainability, which is understood as a natural truth (Wade Reference Wade and Cheater1999; Ulloa Reference Ulloa2004). Also flourishing is the New Age medicine market, which uses imaginaries about ethnic spirituality (Wade Reference Wade and Cheater1999) primarily for mercantile and individualistic purposes (Sarrazin Reference Sarrazin2022), and European Indian hobbyist movements that attempt to embody and solidify romanticized ideas about indigenous peoples and disregard the history of their exploitation (Balán Reference Balán2023). As for nongovernmental organizations, there are some indigenist ones that sacrifice the needs and ethical dilemmas of the real Indian and exalt the “hyperreal Indian,” who is functional in light of their ideals (Ramos Reference Ramos1994). Additionally, industrialized and romanticizing tourist souvenirs are passed off as traditional (Phillips Reference Phillips, Phillips and Christopher1999; Jonaitis Reference Jonaitis, Phillips and Christopher1999; Steiner Reference Steiner, Phillips and Christopher1999). There is also a burgeoning of economic pyramids with indigenist discourse, as well as companies that capture the alleged identities and rights of indigenous peoples to create economic empires and declare their sovereignty from the state (Comaroff and Comaroff Reference Comaroff and Comaroff2009). And the capstone of the negative influence of the myth of the Natural Man is the justification of endemic violence, low wages, and neocolonialism in the Global South, driven by deterministic ideas linked to racial and ethnic essentialisms (Trouillot [Reference Trouillot and Gnecco2003] Reference Trouillot and Gnecco2011; Balán Reference Balán2023).

The myth of the Natural Man

Columbus came to the West Indies carrying imaginaries about the creatures that inhabited the distant lands inherited from Ancient Greek and Medieval philosophers, theologians, writers of fantasy literature, and travelers such as Homer, Herodotus, Aristotle, Pliny, St. Augustine, St. Isidore of Seville, Pierre d’Ailly, Alexander the Great, Mandeville, and Marco Polo. Therefore, his expectations of what he was going to find were filtered through mythological, biblical, and teratological lenses (Palencia Roth Reference Palencia Roth and Arnold1996). These traditions of thought contributed to Columbus’s contradictory imaginaries about the indigenous people he would find. The myth of the Natural Man reunites both the Edenic and cannibalistic perspectives on the indigenous people, which Columbus started in the Americas. I focus here on the Edenic view. In the first letter to Luis de Santangel (February 15, 1493), Columbus described the new lands as a paradise full of fresh water, natural ports, mountains, fruits, honey, spices, gold, and other metals—richness without end—and easily domesticable and kindhearted people. Columbus described these people as naked, without guns, fearful, loving, innocent, without personal belongings, community based, profoundly linked with nature, and available to be enslaved. Images such as those from America Part One (De Bry Reference Bry1590) (Fig. 1) expanded these imaginaries about America and its peoples through Europe.

Figure 1. Indigenous people in their village carrying out daily activities (De Bry, Reference Bry1590).

Even today the idea of the Natural Man positions indigenous people as having a giving nature. It is still widely believed and strategically exploited the idea that nature created indigenous people with a natural sense of protection for their environment, against all other concerns (Buege Reference Buege1996; Wade Reference Wade and Cheater1999; Ramos Reference Ramos2004; Ulloa Reference Ulloa2004; Jackson and Ramírez Reference Jackson and Clemencia Ramírez2009). It is commonly thought that indigenous people are an extension of biodiversity, that they are linked with wholeness, that they follow natural cycles by instinct, that they have a natural spirituality and a pure soul. They are still figured in an immutable intermediate stage between animal and human (Amodio Reference Amodio1993; Buege Reference Buege1996; Wade Reference Wade and Cheater1999; Ulloa Reference Ulloa2004), inhabiting a space outside time (Fabian [1983] Reference Fabian2014a, [1983] Reference Fabian2014b). This nostalgic space is similar to Eden, where innocence reigns, and everything is available to be taken without effort. Indigenous peoples are even commonly perceived as a kind of reservoir for “civilized” humans—“positioned in the centre of God’s purposes”— to study their origins, and primordial links, and to delight themselves with their own evolution. Moreover, the current world order allegedly saves us from regressing to states understood as irrational, of impudent nakedness, and superstition. Archaeological museums seem to reinforce and recreate this understanding of ancient indigenous people and the gap with contemporary ones (Gaitán Ammann Reference Gaitán Ammann2006).

Displays in archaeology museums containing pre-Columbian objects seem to whisper: “In these glass boxes we keep these artifacts to show the innocent, natural and great civilizations that nurtured our lands. Admire these pieces, as they are vestiges of our extinct ancestors, and they symbolize our national cohesion and worth. These ancestral sages are different from the indigenous people we had to conquer for the advancement of civilization—a supreme good for all. Here we honour that vanished race.” This fabrication is aided by certain staging and the object’s interaction with labels, maps, and curatorial discourses, which Gnecco and Langebaek Rueda (Reference Gnecco and Henrik Langebaek Rueda2006) emphasize as full of tyrannical categories. These categories used to be ahistorical, aspatial, essentialist, and pretended to find universal types. In recent decades, there has been a difficult movement to shift away from this kind of museum narrative.

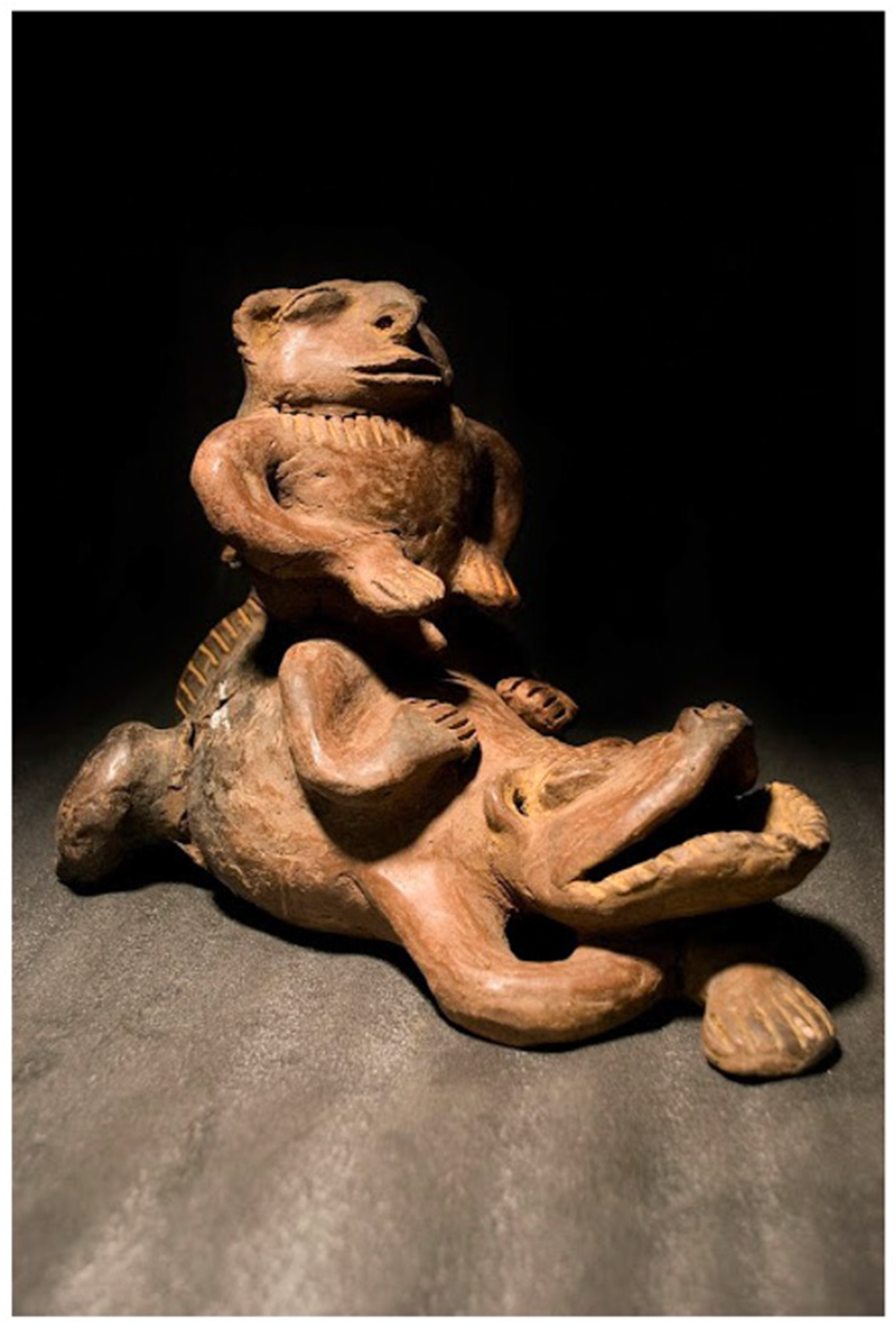

In mainstream museums intended for the admiration of pre-Columbian artifacts, just as in Foglia’s image of an Alzate piece (Fig. 2), the pottery is arranged in a ritualized manner, sharing the room with the viewer but inaccessible. Viewer and object do not enjoy the same air or even the possibility of contact; the objects are in a privileged and illuminated place, and it seems that light emanates from them. Foglia’s photograph places the piece in an inhuman space, empty and without limits. With the exception of the horizontal plane whose confines we do not know, the figure imposes itself in a solitary manner amid the weight of nothingness. Its illuminated presence breaks the blackness that seems to extend toward infinity. Both this piece in the picture and many authentic pre-Columbian ones are arranged as if they themselves radiated light. The museum expedient makes evident the aura of originality that the pieces are meant to exhibit. The pieces are energy centers that permeate the space.

Figure 2. An Alzate pottery piece now at University of Antioquia Museum (untitled photo by Andrés Foglia, 2009).

This particular energy that the museum rhetoric makes emerge from them is indeed palpable and is justified in the object’s contact with what is usually understood as a “real indigenous person” who is “racially pure.” Moreover, indigenous people would represent a whole “culture” (Clifford [1984] Reference Clifford and Reynoso1998; Price Reference Price1989; Field Reference Field2009; Holtorf Reference Holtorf2013). That is, the pieces have to be made by an ideal indigenous person who has not been perverted by “civilization,” either biologically or culturally. It is noteworthy that these two concepts still have porous boundaries (Briones Reference Briones1998; Wade [1997] Reference Wade and Wade2010).

In short, the “real” indigenous person is, in the popular imagination and in some expert discourses, someone who re-creates in a continuous present their remote past of sorcerer and savage, who lives in a premodern time and space, following the rhythm of natural laws and tradition imprinted on them. It is from the myth of the Natural Man that they draw their spiritual, feminized, and sacrificial power.

The construction of value and authenticity of pre-Columbian artifacts, their circuits, and the emergence of forgery

Since the late fifteenth century, a transatlantic colonial order emerged that sought to otherize Native American populations to legitimize its extractivist ends (Bonfil Reference Bonfil Batalla1971; Hall [1992] Reference Hall2013; Buege Reference Buege1996; Briones Reference Briones1998, 252; Quijano [2000] Reference Quijano2014, 312; Segato Reference Segato2007, Reference Segato2015; Trouillot [Reference Trouillot and Gnecco2003] Reference Trouillot and Gnecco2011). This colonial order was underpinned by so-called expert knowledge, and modern visual forms of representation that depicted the world and its peoples as available, uncivilized, racialized inhabitants of a distant past, naturally vanishing, and in need of redemption. Paintings, engravings disseminated in books, archaeological artifacts, bones, musealized ruins, national museums, anthropometric and ethnographic photography, cartes de visite, and ethnographic documentaries have been used as evidence to construct the imagination about otherness (Fabian [1983] Reference Fabian2014a, [1983] Reference Fabian2014b; Clifford [1984] Reference Clifford and Reynoso1998; Andermann Reference Andermann2006; Earle Reference Earle2006; MacDougall Reference MacDougall2006a, Reference MacDougall2006b; Juhasz Reference Juhasz, Juhasz and Lerner2006; Poole Reference Poole2000, Reference Poole2005; Reyes Macaya Reference Reyes Macaya2020; Balán Reference Balán2021). Moreover, as Poole (Reference Poole2000) would say, the visual economy of these images and associated ideas of race contributed to the formation of the European idea of modernity.

These visual representations were coconstituted with essentialist categories and legitimized a historical narrative that naturalized the enslavement, long-lasting subalternization, and the fixation of certain ideas about indigenous people in the popular imagination. It is worth noting that sometimes indigenous peoples themselves have strategically contributed to this imagination about themselves linked to Nature, mainly to gain access to certain rights, to deal with governments, and to attract tourists (Buege Reference Buege1996, 86; Phillips Reference Phillips, Phillips and Christopher1999; Steiner Reference Steiner, Phillips and Christopher1999; Jonaitis Reference Jonaitis, Phillips and Christopher1999; Ramos Reference Ramos2004; Jackson and Ramírez Reference Jackson and Clemencia Ramírez2009; Del Cairo Reference Del Cairo2011). Some of these essentialist categories are race, primitive, indigenous people, uncivilized, savage, cannibal savage, noble savage, Natural Man, and people without history. Authors such as Dussel (Reference Dussel1992) and Trouillot ([Reference Trouillot and Gnecco2003] Reference Trouillot and Gnecco2011) stress that even modernity and its fellow concept progress would not have been possible without such categories. As previously emphasized (Balán Reference Balán2023), there have been antihegemonic scopic regimes that proposed alternative narratives about indigenous peoples, such as in Los mulatos de las esmeraldas (Sánchez Gallque 1599) and in Nueva crónica y buen gobierno (Poma de Ayala [1615] Reference de Ayala1980).

Until the eighteenth century, pre-Columbian objects were conceived as obstacles to evangelization, as they were seen as diabolical idols, “imbued with an evil aura” (Botero Reference Botero2001, 1–50; Achim Reference Achim, Phillip, Podgorny and Gänger2014, 27). For this reason, colonial authorities justified the confiscation and exorcism of emeralds, the melting of gold objects, the destruction of ceramics and temples, the public burning of “seashells, vessels, pitchers, blankets, idols made of cotton and wood, stuffed macaws, human-shaped figures made of wood or cotton, head-dresses of different kinds of feathers and the clothing they wore when ‘they were singing to the devil in their temples’” (Botero Reference Botero2001, 19). Only a few of these objects survived as gifts to the crown. They were offered as tokens of the conquered territories. The first recorded collection of pre-Columbian objects was sent by Montezuma in 1519 to the king of Spain (Botero Reference Botero2001, 32–33). In Europe, unlike in New Granada, during the colonial period, the objects were considered curiosities or works of art (Botero Reference Botero2001, 8).

Botero (Reference Botero2001, 50) locates the origin of collecting pre-Colombian artifacts in New Granada at the end of the eighteenth century in the work of Father Julian, Caldas, Duquesne, and Humboldt, who began to understand pre-Columbian objects as the fruit of great civilizations, and their makers as artists with advanced technical skills. Moreover, Botero (Reference Botero2001, 6–7) states: “During the nineteenth century, the past began to be visible in Colombia. Alexander Von Humboldt reintroduced ancient America to Europe after his scientific journey through Spanish America, 1799–1804. He publicized the pre-Hispanic monuments of the Muiscas, the former inhabitants of the high plateau of Cundinamarca and Boyacá.”

Botero (Reference Botero2001, 7) locates three forces that led to the development of interest in pre-Columbian societies in Colombia: Colombian scientists strongly influenced by European ideas and commercial notions began to consider objects as antiquities that should be preserved; based on French romanticism (which idealized the harmonious relationship of the “primitive” with nature), a romantic literary trend “that enhanced the mythological roots of the Colombian nation in its indigenous past” emerged in Colombia (7); and the rise of guaquería in the Antioquian colonization.

Piazzini (Reference Piazzini2009) explains the circuit, actors, and social practices that contributed to the emergence of the category of artifacts called “indigenous antiquities” during the second half of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The author explains that indigenous antiquities had their origins in natural curiosities and antiques and later became “archaeological evidence” (49). The characters involved were “the guaquero colonizer, the antiquarian merchant, the man of letters and sometimes the foreign collector and scholar” (50). Since the end of the eighteenth century, the Antioquian colonization of western Colombia took place. According to the author, the colonists saw guaquería and agriculture as a means of subsistence, and by the mid-nineteenth century, guaquería was considered a traditional trade. For Codazzi (qtd. in Botero Reference Botero2001, 81), guaquería was “the only systematically established industry.” Botero (Reference Botero2001, 84) along with Piazzini describes the value system of the guaquería as greed for a reward mixed with protection against evil spells, visions of blue fires, and strange sounds that emerged from profaned tombs.

These practices of searching for pre-Columbian pottery and carved gold were favored by the colonial economic system, in which “the merchant granted credit in kind to the colonist, and the latter, in exchange, paid him with the fruit of his excavations” (Piazzini Reference Piazzini2009, 52), and by laws, such as that of 1883, which gave ownership of pre-Columbian objects to whoever found them (Duque 1965, qtd. in Piazzini Reference Piazzini2009, 51). Piazzini speaks of other modalities of exchange, including proposing a “guaquería adventure” to travelers. This consisted in accompanying the empirical experts to the excavation of a guaca during the day and then buying the pieces from the guaqueros (53). Travelers were the first target of the Alzates’ fake pieces (Vélez Reference Vélez1966, 159).

At the same time, in the cities, the figure of the antiquarian and literate was consolidating. Following Schnapp, Achim (Reference Achim, Phillip, Podgorny and Gänger2014, 27) states that it was in the eighteenth century, when there was an epistemological transition when, in addition to texts, objects began to be a reliable form of evidence for antiquarians. This meant the dissection of objects through the senses, as was done in the natural sciences. The figure of the antiquarian had emerged because of an imperial Spanish policy devoted to the study of ruins across the empire, and inside the Creole elite, who attempted to modify histories by philosophers such as Voltaire who undermined America’s place in the history of civilization (Achim Reference Achim, Phillip, Podgorny and Gänger2014, 27–28). In contrast, Piazzini (Reference Piazzini2009, 56) notes that antiquities also “functioned as symbols of what oneself was not or did not want to be … [;] the civilized and modern is expressed by comparison with the barbaric or antiquated,” located outside of history. Moreover, Sellen (Reference Sellen, Phillip, Podgorny and Gänger2014b) notes that antiquities were used as gifts that served to enrich the collector’s social circle. By writing about the pre-Columbian past, antiquarians added symbolic capital to the objects as scarce collection goods (Piazzini Reference Piazzini2009, 53–54, 56), which operated as “objects of prestige and markers of identity.”

In the mid-nineteenth century, the figure of the counterfeiter emerged as one of the characters involved in this market (Piazzini Reference Piazzini2009, 66). Franck even predicted as early as 1831 the forthcoming emergence of counterfeiters in Latin America, particularly in Mexico (qtd. in Sellen Reference Sellen2014a). Forgery has a long tradition in Europe, but for (what is now known as) Latin America, it was new—the category of “fake” existed only in socioeconomic frameworks that treasured objects linked to certain conceptions of authenticity. Even nowadays, the market of copies and fake pre-Columbian art continues to flourish. For example, Brulotte (Reference Brulotte2012) analyzes this market and artisans’ life history at Monte Albán, an archaeological site in Arrazola, Oaxaca.

In relation to forgery, it is important to note that at the end of the nineteenth century, definitions of authenticity emerged as an anthropological by-product of cultural evolutionism (Phillips Reference Phillips, Phillips and Christopher1999, 45). In her study on the trafficking of souvenirs embroidered with indigenous motifs (Fig. 3) from Canada to Europe, Phillips (Reference Phillips, Phillips and Christopher1999, 49) notes that when notions of authenticity linked to the makers’ race were imposed, indigenous people began to erase from their production anything not considered “purely indigenous” by European buyers: “For some years, only the Plains Indians had been able to meet the criteria of Indian ethnicity established by scientific ethnology and the embryonic primitivist movement within art history, and Woodlands Indians would increasingly replace elements of their earlier dress with the pan-Indian styles derived from Plains clothing.”

Figure 3. An example of moose hair embroidery with indigenous motifs made for the tourist industry by nuns in Quebec. (Birchbark Box with Hearts Decorations, 1780-1800). Library and Archives Canada/Cartwright fonds/e010948520).

In addition, indigenous people took advantage of the symbolic capital of their racialized origins to appropriate a market they had previously shared with nuns, the main producers in colonial times of embroidery with indigenous motifs. It is surprising that the souvenirs produced by the nuns are still presented in museums around the world to depict, for example, Woodland Indians, and that these were made according to ideas imported from Europe about the Natural Man, understood as an ecological and instinctive alternative to the civilized world. Despite the nuns’ deep knowledge of the dress, practices, and ways of life of their Woodlands Indian neighbors, they still made objects that perpetuated the idea of the romanticized Natural Man for the European market (Phillips Reference Phillips, Phillips and Christopher1999). Similar cases are reported by Steiner (Reference Steiner, Phillips and Christopher1999) on African art and Joniatis (Reference Jonaitis, Phillips and Christopher1999) on Alaskan totem poles.

What interests me primarily about Phillips’s (Reference Phillips, Phillips and Christopher1999, 48) study is that the author notes that, as early as the late nineteenth century, indigenous artists produced their ethnicity in transnational and local dialogues: the narratives in the embroideries and their markers of otherness were made in such a way as to make sense for both indigenous people and for the sensibilities of the European ruling classes. In addition, the artists modified some differential diacritics to deploy certain visions of indigeneity that were convenient for them, in accordance with what was considered preferable in each era. Moreover, Phillips says that this polyvalence probably explains the persistence of the iconography of the Natural Man. This polyvalence, fed by a symbolic market with varied actors and interests, also contributes to the vitality of the myth of the Natural Man printed on the fake pre-Columbian Alzate pottery.

Contemporary artisans who sell fakes or replicas of pre-Columbian artifacts (such as those depicted by Brulotte Reference Brulotte2012, 44) also have this understanding and immersion in transnational networks who validate the objects’ authenticity and worth. These networks “include international museum worlds, archaeological practice, and heritage tourism” who constitute the circle of the connoisseurs. Nonprofits and environmentalist and developmentalist discourses are also part of this network (Gros Reference Gros2000; Ramos Reference Ramos1994; Ulloa Reference Ulloa2004; Jackson and Ramírez Reference Jackson and Clemencia Ramírez2009). Clifford ([1984] Reference Clifford and Reynoso1998) and Price (Reference Price1989) identify the unequal power relations historically traced by anthropologists, museums, missionaries, colonial administrators, travelers, and connoisseurs with indigenous peoples through the theft, larceny, deception, and extortion of their artworks. As I mention elsewhere (Balán Reference Balán2021), regarding museum practices in the twentieth century, Price (Reference Price1989, 78) states that

collectors and museums decide which works of “Primitive Art” to “safeguard,” bypassing the priorities of their owners, … claiming the obligation to … “contribute to human knowledge” (75) within museums…. Western connoisseurs reserve the right to interpret objects…. They use financial and communicational resources to give recognition to their preferred objects among all the “anonymous” of the “third world.” They are introduced into market dynamics that both justify the extraction and modify social relations in communities and with outsiders, their economy, the role and meaning of collected objects, and the creation of new arts as a result of contact.

Nowadays, these colonial ways of dealing with objects made by people still considered the Other from “the West” are being questioned. The pieces are being historically contextualized, and indigenous peoples are asked whether and how the pieces can be displayed to account for and not affect the community’s social relations, schemes of values, and sacred places. This is transforming hegemonic Western ways of understanding indigenous and nonindigenous art, as well as the global art market. Nevertheless, despite the significance of these new ways of curating, we cannot without nuance state that this is a defetishization and decolonialization of indigenous art. Being deeply intertwined with hegemonic categories and practices, even indigenous curators sometimes reproduce dominant forms of discourse, image making and exhibition. And this may be unintentional or a form of strategic essentialism (Ramos Reference Ramos2004).

In short, fakes, in Sellen’s (Reference Sellen2014a, 160) words, “are situated in time, reflecting contemporary trends and responding to demands from the market … [they] inform us about the intricacies of social agency and networks, as well as about the tastes and trends of a certain period.” Precisely because of this understanding of the market, its agents, and the value added to the objects when the creators underline their indigeneity, artisans employ a strategic essentialism that links them with Nature, the rural, the nonindustrial, the ethnic, traditional ways of living, and handmade production of the pieces. By such strategy, they show themselves to be natural heirs of pre-Columbian indigenous people, which increases the pieces’ value (Brulotte Reference Brulotte2012, 44, 47). Brulotte (Reference Brulotte2012) points out disputes related to this type of ethnic/racial identities assumed by replica sellers in front of foreign buyers and locals, in which essentializing notions proliferate in definitions about what a “pure” indigenous person is, when an indigenous person ceases to be so, and who has the right to claim those identities. Brulotte also notes that replicas break down rationales of cultural heritage naturalized by the state and the tourist market, and that in their social lives, they acquire values depending on the circuit, the buyers, and how they are cataloged.

Brulotte (Reference Brulotte2012, 49) stresses that crafts such as the one from her case study, and the town where they are commercialized, are products of the twentieth century but are usually depicted as a premodern remnant—something similar happens with the flourishing of totem poles depicted by Jonaitis (Reference Jonaitis, Phillips and Christopher1999), African art (Steiner Reference Steiner, Phillips and Christopher1999), and other cases (Bueno Reference Bueno2021). What is usually popularly considered the most traditional and antique is actually a fabrication, or at least a reconstruction with a well-studied narrative and an orchestrated mise-en-scène.

Alzate pottery in the Global North

As for the collection of fake pre-Columbian pottery addressed here (Fig. 4), several reputable scholars have vouched for the pottery’s authenticity. One of whom was Delachaux (Reference Delachaux1914), director of the Ethnographic Museum of Neuchâtel starting in 1921, and then director of the Museum of Natural History of Neuchâtel in 1945 (Gómez Gutiérrez Reference Gómez Gutiérrez2011). He published a study defending the pieces from those who branded them as fakes, based precisely on ideas related to the Natural Man. He stated various things on the pottery (1914):

Their forms are full of unexpected elements, the invention is so fruitful, the movements denote such an intense observation of nature. (1071) [empahsis mine]

It is evident that they were not made for domestic use; they are not household utensils. Would they have been consecrated to the cult of the dead? Would they have been the object of an industry? Would their images have had a symbolic or religious meaning? (1072) [empahsis mine]

It is the living and mobile beings that interest our artists; they must have observed them in their most characteristic movements. Their fantasy went even further. Like the medieval artist, they evoked a whole imaginary fauna as vital as the real one and sometimes singularly disturbing. (1072) [empahsis mine]

Mr. [Sebastián] Hoyos, in the preface to the catalogue of the Arango collection … thinks that these black ceramics must have belonged to a civilization that had already disappeared at the time of the Spanish conquest. (Delachaux qtd. in Gómez Gutiérrez Reference Gómez Gutiérrez2011, 432; translation by the author) [empahsis mine]

We have no other hypothesis but to see in this village destroyed by the Quimbayas the authors of our pottery. As for the idea of considering them as the product of present-day Indians, or at least after the conquest, it seems to us very unlikely. The absence of representation of persons dressed in European style or of horsemen, so frequent in the ceramics of other present-day Indians, as well as the total absence of European influence of any kind, would be particularly exceptional. (Delachaux qtd. in Gómez Gutiérrez Reference Gómez Gutiérrez2011, 433; translation by the author) [empahsis mine]

Figure 4. A page in Arango collection’s catalog.

In these statements from Delachaux, a romanticized notion of the mythical Natural Man prevails. This is evident in assumptions such as their affinity for the wild, living forms, their alleged observant sensitivity to their environment, their dead cults and religious symbolism, their free and inspired spirit, and a somewhat disturbing mysterious air. These brief passages bring together the persistent dual perception of the “primitive” that Price (Reference Price1989) stresses. That is, the Natural Man is assumed to be a primordial link that acts collectively—without individual agency, someone of “pure” spirit who wisely follows nature: an alternative model of being to the individualistic and fragmentary decadence of “civilized” modernity. In contrast, there is an allusion to certain esoteric pagan rituals, which are regarded as savage, incomprehensible, and somewhat tenebrous. This imaginary being is positioned as extinct, and Delachaux’s confirmation bias inhibits the contemplation of the possibility that contemporary indigenous people, mestizos, or whites decide to erase all European traces to better commercialize the pieces.

As early as 1909, anthropological texts published by the American Museum of Natural History of New York (Meade Reference Meade1909) showed doubts about the originality of the pottery of concern. The museum had purchased approximately 150 pieces from the mining engineer Frederick F. Sharpless, who told them that they came from Quinchia and Papyal. Others were received as gifts from Francis C. Nicholas. In these writings, it is said that several anthropologists who reviewed the pieces denounced them as fakes. However, later, “very reputable travelers” (connoisseurs) saw the pieces and affirmed they were identical to those found by miners in the region. Ward brought to the museum a portion of the collection, which was certified by the antiquarian Leocadio María Arango, and the American Museum of Natural History of New York also knew about other large private collections (Meade Reference Meade1909, 333). All this led the museum to accept the collection as valid despite previous doubts (Meade Reference Meade1909, 333). As Price (Reference Price1989) says, the value of the artworks is constructed and validated through their pedigree, which is the history of owners of the pieces and of where they were first found. For Vélez (Reference Vélez1966, 156–157), the guarantee given by Arango carried weight because he was considered an expert on the subject, he lived in the country where the pieces had been found, and he had an extensive collection of them. Botero (Reference Botero2001) even says that Arango was the largest collector at the time. It must be stressed that little was known about the prehistoric and cultural context of the objects: there was no certainty about the iconography, carving style, manufacture, or materials. Saville (Reference Saville1928, 146), who had been director of the Museum of Natural History in New York when the pieces were acquired, says that almost all the museums in Europe and the United States had specimens of the pottery. He adds that a large number were circulating in New York at very low prices, which made it unlikely that they were manufactured for commercial purposes (146).

Nevertheless, Vélez (Reference Vélez1966, 156) reports that at the first International Congress of Ethnology in 1912, Seler and Von Den Steinen presented arguments that led them to conclude that the pottery pieces from Colombia were fakes (Fälschungen). Furthermore, in 1920, Montoya y Flórez (who later became president of the Academia Antioqueña de Historia) spread news worldwide that he had discovered the authors of the hoax: the Alzate family (157), allegedly with three generations in the business. However, Vélez (Reference Vélez1966, 167) says that Montoya y Flórez was just the one who spread the discovery done by the European professors. Vélez states that it was at those times when the collection was first labeled “Cerámica Alzate,” and he affirms that it was a “scientific farce that caused worldwide controversies” (157, 171)—so much so that this was one of the topics discussed at the first International Congress of Ethnology. There, archaeological practice advanced in its formalization and protocolization. I would venture to say that, in this sense, the business of fake pottery made in Medellín enjoys the prestige of having advanced scientific methods in international archaeological practice.

The birth of national museums as political arenas and places of legitimation through mythical civilizations

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, after independentist fights, the Creole elites of the nascent Latin American republics felt the need to appease the inequalities among the inhabitants of their territories that had persisted since colonial times and give the republics a national identity artificially united by race and land (Wade Reference Wade, Nancy and Anne2003), while also creating an image that would justify their promising future. To create that image, museums were prominent places, where “material representations of ideals, values, needs and tastes could be exhibited with particular purposes” (Gaitán Ammann Reference Gaitán Ammann2006). Thus, the elites patrimonialized the glorious ruins of “ancestral empires,” civilizations that they labeled as disappeared, made of extinct races. These races were positioned as the substrate of the nation.

That is, the elites dissociated contemporary indigenous people, “who [they said] did not know to appreciate or properly use antiquities, land or natural resources” (Achim Reference Achim, Phillip, Podgorny and Gänger2014, 41) from this heritage (Earle Reference Earle2006) they had looted. Archaeology favored this ideology by also neglecting the continuity of the bone record (Achim Reference Achim, Phillip, Podgorny and Gänger2014, 41). In that sense, pre-Columbian material was positioned as coming from an immemorial, mythical, and quasi-phantasmatic time, and the vestiges were imbued with a legitimizing agential capacity. Thus, the artifacts were interwoven with a narrative and an expository rhetoric that contributed to their fetishization. This fetishization and rupture between past and present-day indigenous groups that persists at the Gold Museum in Bogotá, Colombia, is what Gaitán Ammann (Reference Gaitán Ammann2006, 230, 238–239) calls the contradictions of the golden alienation.

In brief, the Creole elites appropriated an “ancestral” indigenous legacy that would serve as a bulwark against the outside world, but in the private sphere, they despised contemporary indigenous people. In this way, independence was legitimized by the revenge of ancestral peoples, whose lineages were interrupted by the conquest, lineages from which the Creole elite claimed to descend (Langebaek Rueda Reference Rueda and Henrik2008).

National museums were privileged places for organizing a logical plot of social hierarchies that needed to construct “pure” and uncontaminated identities validated by racial ideas linked to the myth of the Natural Man to fix the place that indigenous people would occupy in the nation (Pinochet Reference Pinochet Cobos2016; Earle Reference Earle2006). In fact, today’s way of exhibiting pre-Columbian objects still involves the essentialization of indigenous social life in the past (Gaitán Ammann Reference Gaitán Ammann2006, 230). The peripheralization that persists even today of contemporary indigenous people cannot be seen as dissociated from the will to conquer their territories, expropriate their work, and extinguish any trace of “barbarism” that obstructed the advance toward much-desired modernity. National museums served as a legitimizing authority, pedagogical places for citizens, repositories of identity symbols, and microcosms of the nation (Pinochet Reference Pinochet Cobos2016). Alzate pottery contributed to cover this need for pre-Columbian pieces for the Museo Nacional de Colombia (Colombian National Museum), and its educational, evidential, and hierarchizing purposes. Moreover, the pottery nurtured museums in the Global North and their rhetoric of appropriating distant lands.

Regarding the scientization of archaeology methods in Colombia, it was not until 1941 that the National Ethnological Institute was created, which then institutionalized archaeology as an auxiliary science to anthropology. Piazzini (Reference Piazzini2009, 67) notes that archaeological research became protocolized, which involved “the collecting of evidence in situ through fieldwork and data analysis in the laboratory. Indeed, some things changed: circulation circuits, the trajectories of transformation of archaeological artifacts, as well as the places of production and the forms of reproduction of knowledge.” It was then that pre-Columbian pieces became “archaeological evidence.”

Despite nineteenth-century elites’ deep political interest in pre-Columbian pottery, goldwork, and ruins, it was not until the early twentieth century that a series of laws prevented trade in indigenous antiquities: “Law 39 of 1903 provides for the organization of the museums of the Republic and the publication of the existing catalogues, while Law 48 of 1918 recognizes pre-Columbian monuments as being Patriotic Historical material, and Law 47 of 1920 prohibits the exportation of any historical object of interest for the country without prior permission” (Duque 1965 qtd. in Piazzini Reference Piazzini2009; see also Botero Reference Botero2009). And it was in March 1939 when “Colombia’s Ministry of Education formally requested that the national Central Bank purchase a Prehispanic goldwork masterpiece that was at risk of being sold to a private collector” (Botero Reference Botero2001 and Sánchez 2003 qtd. in Gaitán Ammann Reference Gaitán Ammann2006, 230). “In December 1939, the Bank officialised its engagement with ancient goldwork collecting which, in time, would result in the creation of its world-famous Gold Museum” (Gaitán Ammann Reference Gaitán Ammann2006, 230).

In the 1820s, all throughout Latin America, national museums proliferated (Earle Reference Earle2006), and a series of laws prohibiting the export of pre-Columbian “materials” was implemented afterward. However, lack of vigilance over the guaqueros facilitated the expatriation of pre-Columbian “relics” to museums in the Global North (Earle Reference Earle2006). A paradigmatic example of such expatriation is the sale of a gold raft with human figures atop it that has been celebrated since 1856 as material confirmation of the legend of El Dorado (Hettner 1888 and Zerda 1873, qtd. in Gaitán Ammann Reference Gaitán Ammann2006, 228). It was sold between 1877 and 1880 to the ethnographic museum in Berlin, whose shelves never saw it: “It is said to have mysteriously disappeared in a fire that ravaged the warehouses of the museum in the port of Bremen” (Gaitán Ammann Reference Gaitán Ammann2006, 228; Field Reference Field2012).

Evidential rhetorics of the Alzate mise-en-scène and the myth of the Natural Man

To create authentic pre-Columbian fakes, the Alzates had to understand very well the expectations of international and national collectors and scientific dealers, including who the artisans of pre-Columbian pottery were, what kind of artifacts they made, how the ancient inhabitants of these lands buried their pottery, and how the pottery should look in order to have been made in a mythical past. That is, they had to be aware of what diacritics the pieces should have for these connoisseurs to experience the nostalgia of pre-Columbian pastness (Holtorf Reference Holtorf2013). Pastness is an object age-value or an object’s condition of being perceived as from the past. Some experience pastness in a situated cultural context, irrespective of the qualities inherent in its material substance (Holtorf Reference Holtorf2013). As Holtorf (Reference Holtorf2013) states, authenticity layers can be added despite the absence of a social history and traces of years in the materiality of the object. For the people to experience pastness, it was not only a matter of the pieces following the expected forms, symbolisms, decay, tearing, and disintegration; the Alzates also had to stage the discovery and unearthing of the guacas, “a narrative that linked their past origin and contemporary presence” (Holtorf Reference Holtorf2013, 434). As if that were not enough, they inserted pebbles inside the ceramics, knowing that there was the illusion that they contained gold (Vélez Reference Vélez1966, 161) because of the El Dorado legend.

Examples of cultural products and places regarded as ancient and traditional but made of plurivocal or palimpsestic dialogues and appropriations of tastes, materials, symbols, and iconographies between indigenous peoples and hegemonic powers were mentioned previously. It is notable that, for example, the contemporary Mexican forger Brígido Lara made pottery that was considered original in institutions such as “The Dallas Museum of Art, the Morton May collection at the Saint Louis Art Museum, New York’s Metropolitan Museum,” and collections with high symbolic capital in France, Australia, Spain, and Belgium (Lerner Reference Lerner2001). Moreover, Lerner states that Brígido Lara “may have been so prolific that he had a hand in shaping what is today understood as the classic Totonac style.” He adds, “Archeologists have used his objects to draw inferences about the ancient world, Lara is guilty of adding misleading data to the pool of available evidence.” Just as Alzate pottery.

Much of the mystique surrounding Alzate pottery was because those who found them could boast of discovering treasures that had been hidden for centuries, in the same way that the conquistadors imagined the West Indies as a place close to paradise, if not paradise itself (see Columbus Reference Columbus1493; Langebaek Rueda Reference Rueda and Henrik2008), full of gold, silver, primitive people available to be enslaved, and beautiful libidinous women, all ready for the taking. Let’s imagine it: we cross the Atlantic or the continent on an enlightened expedition to supply private collections or museums in the Global North with the idea that Americans in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries are still unaware of the real value of pre-Columbian relics. Guaqueros take us on an “exclusive” expedition (Vélez Reference Vélez1966, 159; Piazzini Reference Piazzini2009) during which we see with our own eyes how the objects, buried for centuries as gifts from the indigenous people to their pagan gods or ancestors, come to light to be treasured by our centers of social, political, scientific, and economic power with the objective of knowledge for future generations and symbolic appropriation of the world and its wonders (Clifford [1984] Reference Clifford and Reynoso1998; Price Reference Price1989). Far from superstition, the noble spirit of research protects us to get these “treasures from the ground” (Pillsbury Reference Pillsbury, Phillip, Podgorny and Gänger2014, 57).

The pieces were also validated in their authenticity by renowned collectors such as Don Leocadio, an enthusiast of these objects and private collector, but above all a politician and great Antioquian businessman of “impeccable lineage.” On many occasions, Don Leocadio himself acted as guarantor of the originality of certain pieces exported to private collectors and to international museums of very high cultural capital (Meade Reference Meade1909; Vélez Reference Vélez1966). In addition, the pieces were assigned to places of origin among the most explored archaeological zones of the time: Apía, Cañaveral, Guasanó (Vélez Reference Vélez1966, 158; for more historical details on Alzate pottery, see Moscoso Marín Reference Marín and Julián2016).

Pascual Alzate told Vélez (Reference Vélez1966, 160) in an interview that the “first Alzate pieces were made based on models of the book of Dr. Uribe Angel,” Geografia general y compendio histórico del Estado de Antioquia, en Colombia, but they also added a few personal touches. How can one not fall for the charms of the newly manufactured mud pieces? Remember, these were people who mostly considered themselves enlightened, who had very few previous pieces with which to compare the new ones, who trusted specialists, and at the same time had an unwavering adventurous, romantic, and commercial spirit (Vélez Reference Vélez1966; Piazzini Reference Piazzini2009).

Still today that feeling of accessing pre-Columbian cultures through clay figures enables spectators to experience a bit of the “magic” that is believed to be impregnated in them. Museum rhetorics are key agents in perpetuating such an adventurous sensation. That is, the materiality of the object is constructed as a channel of communication with the ancient civilizations. There is a sense of contact with a knowledge that is always blurred, cryptic, or lost in time. On the one hand, the objects are positioned as coming from a nostalgic past idealized as pure, unburdened by Western values and hierarchies, a kind of primitive communism in which individuality and the collective merge organically and without friction, given a “natural goodness,” or primordial nobility of spirit, in the style of Rousseau’s lost paradise.

That feeling of the creators’ unconditional surrender to Mother Nature was evocated by the guaqueros through the story of the origins of the pre-Columbian pieces: it was said that they were buried by indigenous people as a gift to the spirits of the territory or to their ancestors. It has also been suggested that the objects were buried as a fertility ritual. And that guaqueros, beings who were half Earth pirates, half descendants of indigenous people, and sometimes even a bit protoscientific (Piazzini Reference Piazzini2009), took them from where they were ritually buried to trade them as exchangeable objects. Furthermore, in looking at the Alzate piece in Figure 5, we cannot help but fix our gaze on the numerous openings that trigger our imagination: Could it be a ritual chicha jug? An instrument for erotic use? A musical instrument? An object to smolder? For holding sacrificial blood? Altered states of consciousness, ritual lasciviousness, disinhibition, narcotic use, healing and purification rituals through blood, haunting rituals are the other side of paths of thought to which we are still accustomed when thinking of indigenous people, as seen in Delachaux’s (Reference Delachaux1914) writings.

Figure 5. An Alzate pottery piece now at University of Antioquia Museum (untitled photo by Andrés Foglia, 2009).

Thus, in the materiality of Alzate pottery, palimpsests and disputed discourses can be differentiated that contributed to generate pastness evocations. As Lowenthal (1985, qtd. in Holtorf Reference Holtorf2013) said, “To be credible historical witnesses, antiquities must, to some extent, conform to modern stereotypes.” Some of these discourses include various styles of original pieces found by the Alzates on their guaquería excursions; pre-Columbian pieces and copies as visually interpreted in Uribe Ángel’s drawings; historical interpretations by local and international scholars; expectations of the researchers sent by international museums; tastes of tourists and amateur national and international collectors; the inventiveness of the Alzates imbued with their era and their strategic use of differential diacritics that evoked the desired Natural Man as an extension of biodiversity; guaqueros’ numerous stories of finding guacas, and their strategic burial and disinterment of the Alzate pieces; and other popular and official discourses and images that circulated at the time surrounding pre-Columbian civilizations.

After the pre-Columbian masquerade

What happens when it is discovered that the supposed pre-Columbian pottery that is treasured and exhibited in a museum was created by a family of Creoles at the end of the nineteenth century? Soon, the ideological castle erected over the objects as giver of their hypnotic ancestral power vanishes and the objects are despised. The expert guarantors of their cultural capital became enraged, attacked the creators, and abhorred the low quality of the works they had previously admired (see Montoya y Flórez 1922, 3; Vélez Reference Vélez1966 on Montoya y Flórez 1922). Suddenly, the pieces became crude imitations of Creole hucksters, ill-intentioned and uneducated people (Montoya y Flórez 1920): “These figures … do not obey any canon and are like monstrous caricatures that closely imitate the art of our Neolithic period” [empahsis mine] (2); they are “mediocre drawings, twisted and of such crude imitation that at first glance they are clearly distinguishable from the legitimate ones” (Montoya y Flórez 1922, 6).

The decadence of the mystique of these pottery pieces dragged down the guarantors of their authenticity and the pedigree chain of the “relics” collapsed like badly fired clay. Just as Piero Manzoni (1961) denounced with his artwork Artist’s Shit and, before him, Duchamp (1917) with The Fountain regarding the construction of the artworks’ value in relation to authorship and their inclusion in artistic circuits and social lives, pre-Columbian pottery gains its value if legitimized with the stamp of a particular ethnic group and invited into certain anthropological circuits. This, thanks to its social life in an art-culture system composed by art curators, anthropologists, collectors, and the general public, who valorize and consume the objects (Clifford 1988, qtd. in Field Reference Field2009; Price Reference Price1989). Pottery loses its value abysmally when discovered that other hands, contemporary, and without a supposed original race made them. Field (Reference Field2009, 510) would say that the pottery is no longer considered ethnographically authentic, meaning that it no longer represents a culture, a standardized mode of production, and an iconic standard.

However, with the passage of time and as a result of a law of patrimonialization, more than three thousand Alzate pottery pieces became national patrimony. Having lost their value as ethnographic objects, they were valued as works of Creole art, reinterpretations of the indigenous past (Rocheraux 1920 qtd. in Vélez Reference Vélez1966; Friengel Reference Friengel2014). Even Vélez (Reference Vélez1966) extolled them as examples of the protoentrepreneurial spirit and of the typical picardía paisa (paisa prank). Vélez (Reference Vélez1966) saw the Alzates as potential popular heroes, and there are those who venture to say that theirs is a precursor collection of contemporary art (Friengel Reference Friengel2014). Today, most of the works have passed into the hands of the University of Antioquia and rest in the museum’s vaults. When some of the pieces are arranged for viewers, it is in a less ritualized way, without indigenist justification but still as local treasure. In other words, Alzate pottery has been reinstitutionalized and is accompanied by its family label of authorship that legitimizes the pieces as authentic pre-Columbian fakes. Field (Reference Field2009) might say that Alzate pottery turned into authentic original high art, which takes inspiration from pre-Columbian pottery of diverse periods and places and intertwines those motifs with original ones following the market taste and their own preferences.

Final thoughts

The decisions that the Alzates took regarding the design of their authentic fake pottery did not arise solely through the imitation of previous pottery that the family had known through their guaquería practices and catalogs; they also emerged in dialogue with stereotypical ideas about the pre-Columbian indigenous peoples that influenced the buyers’ expectations. These ideas took shape through narratives and images that circulated between the emerging Americas and Europe since the late fifteenth century, and the interests of international and local collectors, museum institutions, anthropologists, various elites, popular sectors, tourists, and craftsmen. That is to say, the strategic ethnicity proposed by the figurines was possible given the transnational trade of goods and ideas in which white, Afro-descendant, mestizo, and indigenous people had been immersed since the end of the fifteenth century. Thus, the pottery pieces are part of a wide range of discourses and images that cut across the popular and the scientific, were coconstituted with the constructed Otherness of the West, and contributed to updating and materializing the myth of the Natural Man.

Until 1920, what is now known as Alzate pottery was admired as pre-Columbian, with all the cultural and symbolic capital that implied. It was bought by prominent museums and collectors, and it was taken to be “material evidence” of Colombia’s purported ancient roots and the wise and highly technologized civilizations that populated the territory. When Alzate pottery was thought to be pre-Columbian originals, the pieces nurtured the myth of the pre-Columbian Natural Man. Together with other forgeries, they also nurtured and transformed what was considered authentic pre-Columbian pottery. In contrast, when the pottery was unveiled as a forgery, it revealed the pseudoscientific criteria that lent the verisimilitude of originality to the pieces and their associated history. These authenticity criteria are linked to pastness, constructed in the materiality of the pieces, their mise-en-scène, and a series of validating official and nonofficial agents and institutions.

This and other forgery revelations opened a moment of aporia regarding pre-Columbian cultures and the authority of collectors, archaeologists, and museum institutions. Various scandals were so delegitimizing that they forced archaeologists to professionalize their practices in identifying pieces worldwide. In that sense, Antioquia’s Alzate family deceived a system that claimed to be enlightened and that fixed places in a social hierarchy aided by museums’ rhetorics and written documents. This fixing of indigenous people at the low end of the social hierarchy was based on romanticized racial and identity essentialisms. Some of the “material evidence” upon which these essentialisms were erected were alleged archaeological art and artifacts, bones, and ruins, and their pastness lookalike. As Lerner (Reference Lerner2001) would say about other forgeries, the major political operation of Alzate pottery “subvert[ed] that neo-colonial project which continues to drain Latin America of its cultural heritage.”

There were many clues that the Alzate pieces were not genuine. However, various interests benefited from and even needed the trade in these pieces, whether to create stories of appropriation of distant territories or national histories, as luxury souvenirs, to signal status, or just for commercial purposes. Thus, the myth of the Natural Man, which the Alzate pottery contributed to updating and conveying, is a space of cultural negotiations and a perceptual field in movement. It is constructed dynamically and relationally, in a local and transnational symbolic market. That is to say, the myth of the Natural Man is not solely imposed from the centres of power; it is an arena of cultural negotiations nourished by varied actors and therein lies its vitality. Fakes, copies, and representations of indigenous peoples in everyday images; films; narratives; advertisements; jokes; tourist artifacts; political, developmentalist, environmentalist, nonprofit discourses; and indigenous peoples’ strategic discourses mold what is considered authentic, traditional, pastness bearer, and inherently irreplicable and irreplaceable.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their detailed readings and valuable suggestions, which enabled me to deepen the analysis and find new dimensions to the case study. I am also grateful to Latin American Research Review and Cambridge University Press for their continued support.