Article contents

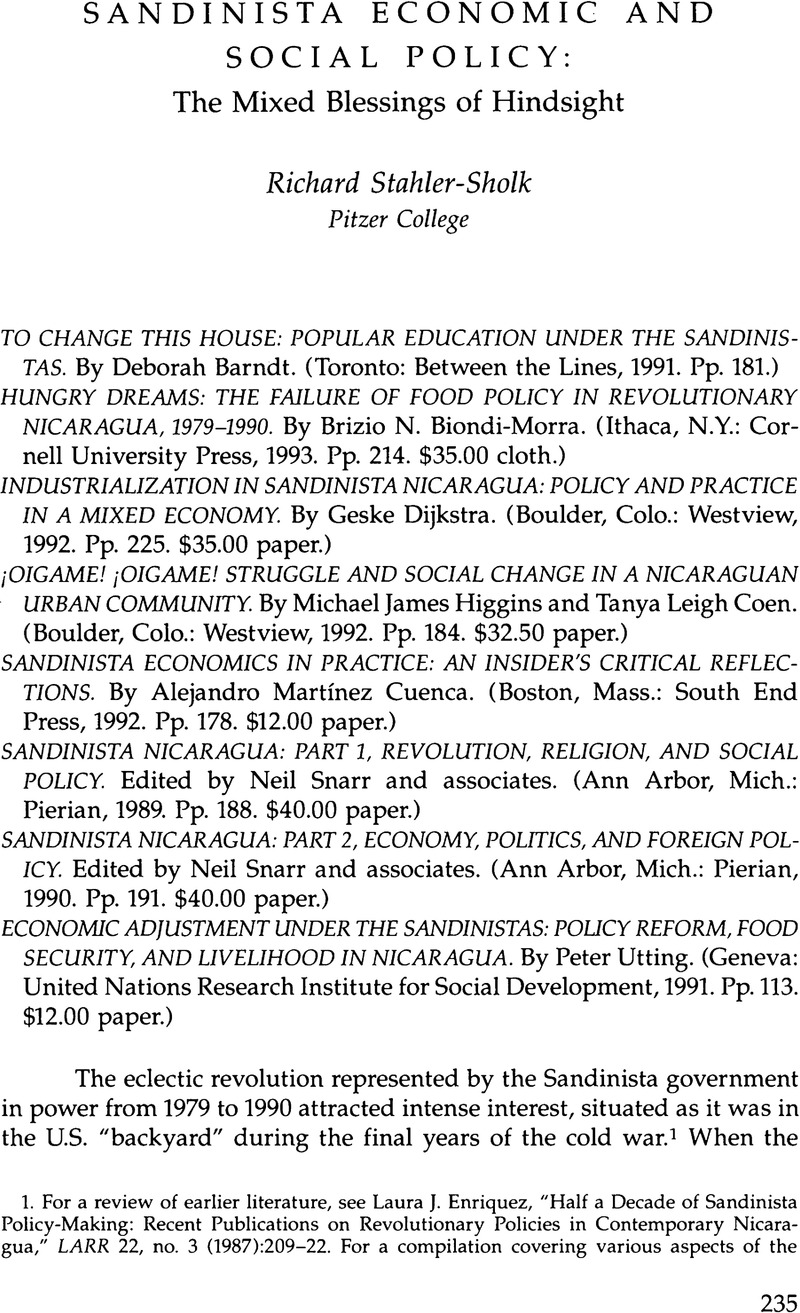

Sandinista Economic and Social Policy: The Mixed Blessings of Hindsight

Review products

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 October 2022

Abstract

- Type

- Review Essays

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © 1995 by the University of Texas Press

References

1. For a review of earlier literature, see Laura J. Enriquez, “Half a Decade of Sandinista Policy-Making: Recent Publications on Revolutionary Policies in Contemporary Nicaragua,” LARR 22, no. 3 (1987):209–22. For a compilation covering various aspects of the Sandinista government, see Revolution and Counterrevolution in Nicaragua, edited by Thomas W. Walker (Boulder, Colo.: Westview, 1991). Other recent overviews include Kent Norsworthy with Tom Barry, Nicaragua: A Country Guide, 2d ed. (Albuquerque, N.M.: Inter-Hemispheric Education Resource Center, 1990); Hazel Smith, Nicaragua: Self-Determination and Survival (Boulder, Colo.: Pluto, 1993); and Harry E. Vanden and Gary Prevost, Democracy and Socialism in Sandinista Nicaragua (Boulder, Colo.: Lynne Rienner, 1993).

2. For post-1990 reassessments, see Nicaragua: Political Economy of Revolution and Defeat, edited by John W. Soule, special issue of International Journal of Political Economy 20, no. 3 (Fall 1990); David Close et al., The Central American Maelstrom, special issue of New Political Science, nos. 18–19 (Fall-Winter 1990); Carlos M. Vilas, “Nicaragua: A Revolution That Fell from the Grace of the People,” Socialist Register 1991 (London: Merlin, 1991), 302–21; and Lisa Haugaard, “In and Out of Power: Dilemmas for Grassroots Organizing in Nicaragua,” Socialism and Democracy 7, no. 3 (Fall 1991):157–84.

3. Comandante Jaime Wheelock, “Medidas económicas forman parte de la defensa de la patria,” Barricada, 13 Feb. 1985, as cited in José Luis Coraggio, “Economics and Politics in the Transition to Socialism: Reflections on the Nicaraguan Experience,” in Transition and Development: Problems of Third World Socialism, edited by Richard R. Fagen, Carmen Diana Deere, and José Luis Coraggio (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1986), 143–70. This growing recognition of problems in economic policy in the mid-1980s is explored in The Political Economy of Revolutionary Nicaragua, edited by Rose J. Spalding (Boston, Mass.: Allen and Unwin, 1987).

4. The outlook for Nicaragua and Central America is discussed in George Vickers and Jack Spence, “Nicaragua Two Years after the Fall,” World Policy Journal 9, no. 3 (Summer 1992):533–62; and Lisa Haugaard et al., “El Pueblo Unido: A Central America Retrospective,” NACLA Report on the Americas 26, no. 3 (Dec. 1992):17–45. For a socialist interpretation of the implications for the Latin American Left, see Shafik Jorge Handal and Carlos M. Vilas, The Socialist Option in Central America: Two Reassessments (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1993); for a social democratic interpretation, see Jorge G. Castañeda, Utopia Unarmed: The Latin American Left after the Cold War (New York: Knopf, 1993).

5. See Orlando Núñez Soto, “The Third Social Force in National Liberation Movements,” Latin American Perspectives 8, no. 2 (Spring 1981):5–21; Amalia Chamorro, Algunos rasgos hegemónicos del somocismo y la revolución sandinista, INIES/CRIES Cuadernos de Pensamiento Propio, Serie Ensayos no. 5 (Managua: Instituto Nicaragüense de Investigaciones Económicas y Sociales and Coordinadora Regional de Investigaciones Económicas y Sociales, 1983); and Edelberto Torres-Rivas, Repression and Resistance: The Struggle for Democracy in Central America (Boulder, Colo.: Westview, 1989). Other histories include James Dunkerley, Power in the Isthmus: A Political History of Modern Central America (London: Verso, 1988); Sandino: The Testimony of a Nicaraguan Patriot, 1921–1934, edited by Edgar Conrad (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1990); and Jeffrey L. Gould, To Lead as Equals: Rural Protest and Political Consciousness in Chinandega, Nicaragua, 1912–1979 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1990).

6. More recent works on religion include Philip J. Williams, The Catholic Church and Politics in Nicaragua and Costa Rica (Pittsburgh, Pa.: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1989); and Michael Dodson and Laura Nuzzi O'Shaughnessy, Nicaragua's Other Revolution: Religious Faith and Political Struggle (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1990). On the Nicaraguan Atlantic Coast, see Carlos M. Vilas, State, Class, and Ethnicity in Nicaragua: Capitalist Modernization and Revolutionary Change on the Atlantic Coast (Boulder, Colo.: Westview, 1989); and Charles R. Hale, Resistance and Contradiction: Miskitu Indians and the Nicaraguan State, 1894–1987 (Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1994). On social policy, see Richard Garfield and Glen Williams, Health and Revolution: The Nicaraguan Experience (London: Oxfam, 1989).

7. See Beth Stephens, “Women in Nicaragua,” Monthly Review 40, no. 4 (Sept. 1988):1–18; Women and Revolution in Nicaragua, edited by Helen Collinson (London: Zed, 1990); Norma Stoltz Chinchilla, “Revolutionary Popular Feminism in Nicaragua: Articulating Class, Gender, and National Sovereignty,” Gender and Society 4, no. 3 (Sept. 1990):370–97; Lois Wessel, “Reproductive Rights in Nicaragua: From the Sandinistas to the Government of Violeta Chamorro,” Feminist Studies, no. 17 (Fall 1991):537–49; Margaret Randall, Gathering Rage: The Failure of Twentieth-Century Revolutions to Develop a Feminist Agenda (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1992); Randall, Sandino's Daughters Revisited: Feminism in Nicaragua (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1994); Paola Pérez-Alemán, “Economic Crisis and Women in Nicaragua,” in Unequal Burden: Economic Crises, Persistent Poverty, and Women's Work, edited by Lourdes Benería and Shelley Feldman (Boulder, Colo.: Westview, 1992):239–58; and Mercedes Olivera and Anna María Fernández, “Subordinación de género en las organizaciones populares nicaragüenses,” in Democracia emergente en Centroamérica, edited by Carlos M. Vilas (Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 1993), 161–86.

8. On the 1990 election, see Latin American Studies Association, Electoral Democracy under Pressure: The Report of the Latin American Studies Association Commission to Observe the 1990 Elections (Pittsburgh, Pa.: LASA, 1990); Jack Spence, “Will Everything Be Better?” Socialist Review 20, no. 3 (July–Sept. 1990):115–32; Carlos M. Vilas, George R. Vickers, and Trish O'Kane, “Nicaragua: Haunted by the Past,” NACLA Report on the Americas 24, no. 1 (June 1990):9–39; William I. Robinson, A Faustian Bargain: U.S. Intervention in the Nicaraguan Elections and American Foreign Policy in the Post-Cold War Era (Boulder, Colo.: Westview, 1992); and The 1990 Elections in Nicaragua and Their Aftermath, edited by Vanessa Castro and Gary Prevost (Lanham, Md.: Rowman and Littlefield, 1992).

9. I contributed to the annotated bibliography in the chapter on the economy.

10. See the ten-volume overview by the Centro de Investigación y Estudio de la Reforma Agraria, La reforma agraria en Nicaragua, 1979–1989 (Managua: CIERA, 1989); El debate sobre la reforma agraria en Nicaragua, edited by Raúl Rubén and Jan P. DeGroot (Managua: Instituto Nicaragüense de Investigaciones Económicas y Sociales and Editorial Ciencias Sociales, 1989); Laura J. Enriquez, Harvesting Change: Labor and Agrarian Reform in Nicaragua, 1979–1990 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1991); and Orlando Núñez Soto, Transición y lucha de clases en Nicaragua, 1979–1986 (Mexico City: Siglo Veintiuno, 1987), which focuses on agrarian transformation. Critical articles include Michael Zalkin, “Nicaragua: The Peasantry, Grain Policy, and the State,” Latin American Perspectives 15, no. 4 (Fall 1988):71–91; René Mendoza, “Costos del verticalismo: un FSLN sin rostro campesino,” Envío 9, no. 107 (Sept. 1990):19–51; Eduardo Baumeister, “Agrarian Reform,” in Walker, Revolution and Counterrevolution in Nicaragua, 229–45; and Laura J. Enriquez, “La reforma agraria en Nicaragua: pasado y futuro,” in Vilas, Democracia emergente en Centroamérica, 123–59.

11. See Ilja Luciak, “Democracy in the Nicaraguan Countryside: A Comparative Analysis of Sandinista Grassroots Movements,” Latin American Perspectives 17, no. 3 (Summer 1990): 55–75; Luciak, “Democracy and Revolution in Nicaragua,” in Understanding the Central American Crisis: Sources of Conflict, U.S. Policy, and Options for Peace, edited by Kenneth M. Coleman and George C. Herring (Wilmington, Del.: Scholarly Resources, 1991), 77–107; and Luis Serra, “Democracy in Times of War and Socialist Crisis: Reflections Stemming from the Sandinista Revolution,” Latin American Perspectives 20, no. 2 (Spring 1993):21–44.

12. Michael Friedman, “The Counterrevolution in Nicaraguan Education,” Monthly Review 43, no. 9 (Feb. 1992):19–28; and Rosemary R. Ruether, “De-Educating Nicaragua: Destroying Knowledge to Destroy a People's Resistance,” Christianity and Crisis 53, no. 4 (12 Apr. 1993):93–94.

13. See, for example, M. Alemán et al., “Survival Strategies in the Popular Sectors of Managua,” Critical Sociology 15, no. 1 (Spring 1988):5–32.

14. Dijkstra's definition includes enterprises with thirty workers or more. For a study of small industry, see Arie Laenen, Dinámica y transformación de la pequeña industria en Nicaragua (Amsterdam: Centro de Estudios y Documentación Latinoamericanos and FORIS, 1988).

15. The use of support prices to win the cooperation of agroexport capitalists is questioned by Vilas in “Unidad nacional y contradicciones sociales en una economía mixta: Nicaragua, 1979–1984,” in La revolución en Nicaragua, edited by Richard L. Harris and Carlos M. Vilas (Mexico City: Siglo Veintiuno, 1985), 17–50.

16. Another intriguing work with a focus more limited to the micro level is Gary Ruchwarger, Struggling for Survival: Workers, Women, and Class on a Nicaraguan State Farm (Boulder, Colo.: Westview, 1989).

17. Biondi-Morra shows 61 percent of agricultural credit going to state enterprises in 1985 (p. 175). Peter Utting's more updated table puts the figure at 26 percent (p. 15), which coincides with other sources.

18. Peter Utting, Economic Reform and Third-World Socialism: A Political Economy of Food Policy in Post-Revolutionary Societies (New York: St. Martin's, 1992).

19. For various perspectives, see Richard Stahler-Sholk, “Stabilization, Destabilization, and the Popular Classes in Nicaragua, 1979–88,” LARR 25, no. 3 (Fall 1990):55–88; Stahler-Sholk, “El ajuste neoliberal y sus opciones: la respuesta del movimiento sindical en Nicaragua,” Revista Mexicana de Sociología 56, no. 3 (July–Sept. 1994): 59–88; Oscar Neira Cuadra and Adolfo Acevedo, Nicaragua, hiperinflación y desestabilización: análisis de la política económica, 1988 a 1991, Cuadernos CRIES, Serie Ensayos no. 21 (Managua: CRIES, 1992); José Antonio Ocampo, “Collapse and (Incomplete) Stabilization of the Nicaraguan Economy,” in The Macroeconomics of Populism in Latin America, edited by Rudiger Dornbusch and Sebastián Edwards (Chicago, Ill.: University of Chicago Press, 1991):331–61; and John Weeks, “The Nicaraguan Stabilisation Programme of 1989 and Prospects for Recovery,” in Economic Maladjustment in Central America, edited by Wim Pelupessy and John Weeks (New York: St. Martin's, 1993), 25–40.

20. From the poem by Padre Ernesto Cardenal, former Sandinista Minister of Culture, “Los estantes vacíos,” Barricada/Ventana, 20 July 1985, p. 8.

- 10

- Cited by