No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

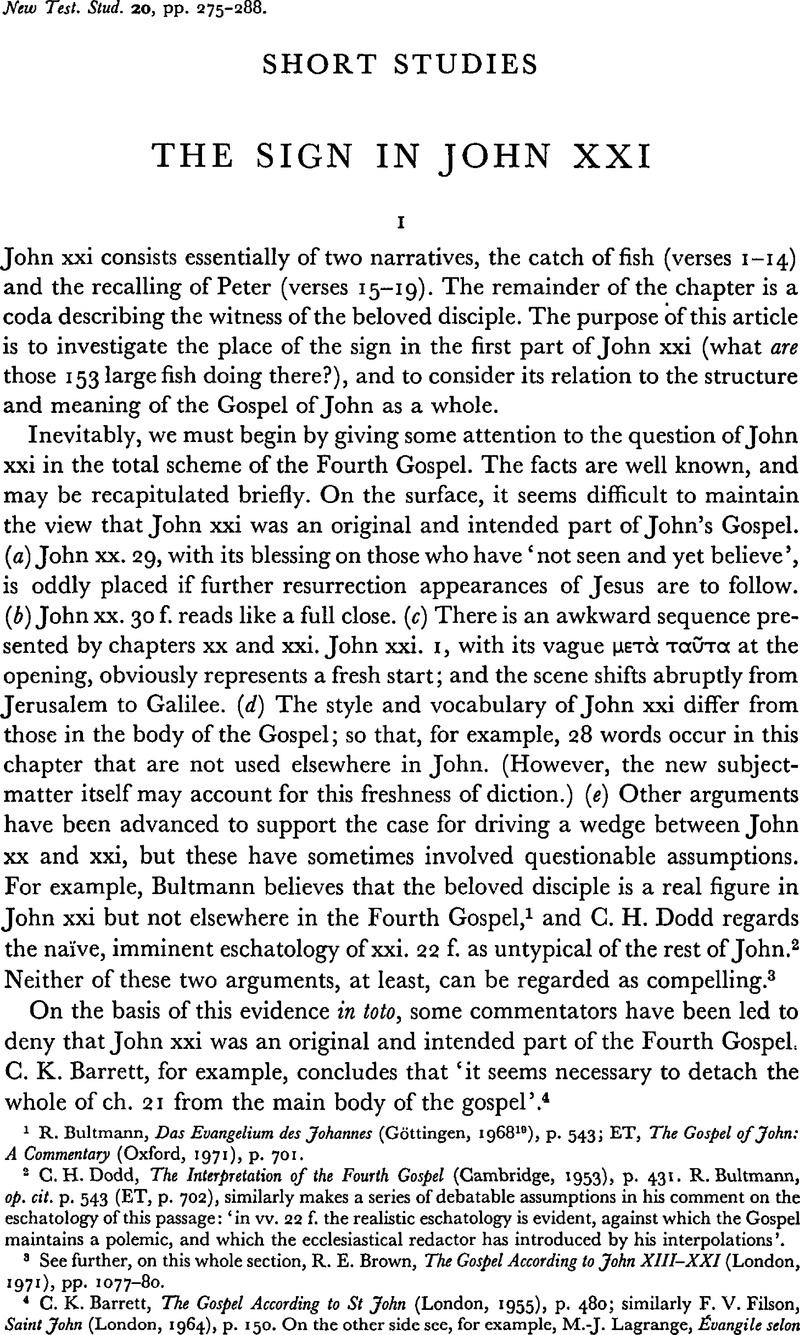

The Sign in John xxi

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 February 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Short Studies

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Cambridge University Press 1974

References

page 275 note 1 Bultmann, R., Das Evangelium des Johannes (Göttingen, 1968 19), p. 543;Google Scholar ET, The Gospel of John: A Commentary (Oxford, 1971), p. 701.Google Scholar

page 275 note 2 Dodd, C. H., The Interpretation of the Fourth Gospel (Cambridge, 1953), p. 431.CrossRefGoogle Scholar R. Bultmann, op. cit. p. 543 (ET, p. 702), similarly makes a series of debatable assumptions in his comment on the eschatology of this passage: ‘in vv. 22 f. the realistic eschatology is evident, against which the Gospel maintains a polemic, and which the ecclesiastical redactor has introduced by his interpolations’.

page 275 note 3 See further, on this whole section, Brown, R. E., The Gospel According to John XIII-XXI (London, 1971), pp. 1077–80.Google Scholar

page 275 note 4 Barrett, C. K., The Gospel According to St John (London, 1955), p. 480;Google Scholar similarly Filson, F. V., Saint John (London, 1964), p. 150.Google Scholar On the other side see, for example, Lagrange, M.-J., Évangile selon Saint Jean (Paris, 1925), pp. 519–21;Google ScholarHoskyns, E. C., The Fourth Gospel, ed. Davey, F. N. (London, 1947 2), pp. 561 f.Google Scholar; Lightfoot, R. H., St John's Gospel: A Commentary, ed. Evans, C. F. (Oxford, 1956), pp. 338 f.Google Scholar See also Marsh, J., The Gospel of St John (Harmondsworth, 1968), pp. 653–60.Google Scholar

page 276 note 1 Morris, L., Studies in the Fourth Gospel (Exeter, 1969), p. 318.Google Scholar

page 276 note 2 For an exhaustive analysis of the literary characteristics of John xxi, see Boismard, M. -E., ‘Le Chapitre XXI de Saint Jean: Essai de Critique Littéraire’, R.B. LIV (1947), 473–501.Google Scholar Boismard concludes that this chapter is not by John himself, but by an ‘anonymous redactor’, a disciple of John, whose style displays affinities with that of both John and Luke (p. 501).

page 276 note 3 Note Barrett, C. K., The Prologue of St John's Gospel (London, 1971);Google Scholar reprinted in Barrett, C. K., New Testament Essays (London, 1972), pp. 27–48.Google Scholar Professor Barrett draws out the intimate relationship in terms of both history and theology between the prologue and the rest of the Gospel of John.

page 276 note 4 Cf. Robinson, J. A. T., ‘The Relation of the Prologue to the Gospel of St John’, N.T.S. IX (1962–1963), 120–9, esp. pp. 124 f.Google Scholar This article is reprinted in Aland, K. and others, The Authorship and Integrity of the New Testament (London, 1965), pp. 61–72;Google Scholar see p. 67.

page 277 note 1 Brown, Cf. R. E., The Gospel According to John I-XII (London, 1971), pp. xxxiv–xxxix.Google Scholar Professor Brown believes that the composition of the Fourth Gospel involved five stages, not three. See also Tasker, R. V. G., The Gospel According to St John (London, 1960), pp. 11–20,Google Scholar for a related theory of authorship.

page 277 note 2 R. E. Brown, op. cit. II, 1078 f.

page 277 note 3 Cf.Bishop, Cassian, ‘John XXI’, N.T.S. III (1956–1957), 132–6,Google Scholar who argues that the epilogue was connected from origin with the rest of the Fourth Gospel, and that it can only be understood now in that context. He finds its key in John x.

page 277 note 4 C. H. Dodd, op. cit. pp. 289 ff.

page 277 note 5 John ii. 1–11; iv. 46–54; v. 2–9; vi. 1–14; ix. 1–7; xi. 1–44. I do not regard the cleansing of the temple (ii. 13–22) or the so-called ‘walking on the water’ (vi. 16–21, where έπί in verse 19 seems quite clearly to mean ‘beside’) as signs in the same sense. For a different view of John vi. 16–21, see C. K. Barrett, op. cit. pp. 232 f.; also Morris, J., The Gospel According to John (Grand Rapids, 1971), pp. 347 f.Google Scholar

page 277 note 6 Significantly enough, it is on just these two counts that Jesus is criticized by the Jews in the confrontation of John vi: because he said he came down from heaven, and because he promised resurrection to every believer on the grounds of his own exaltation (vi. 38–44; cf. verses 61 f.).

page 278 note 1 Lindars, B., ‘The Fourth Gospel and Act of Contemplation’, in Cross, F. L. (ed.), Studies in the Fourth Gospel (London, 1957), pp. 23–35.Google Scholar

page 278 note 2 Cf. Ibid. pp. 30 f.

page 279 note 1 The background to this title is doubtless complex. See C. H. Dodd, op. cit. pp. 230–8, who argues that the expression ό άμνός Το⋯ θεο⋯ here is primarily messianic in meaning. See further, Schnackenburg, R., Das Johannesevangelium I (Freiburg, 1965), 285–9;Google ScholarET, The Gospel According to St John I (London and New York, 1968), 297–301.Google Scholar Schnackenburg believes that the twin ideas ‘servant of the Lord’ and ‘paschal lamb’ are both involved in the title (note p. 288; ET, p. 300).

page 279 note 2 John ii. 13; vi. 4; xi. 55; xiii. 1, al.

page 279 note 3 For a study of the Johannine doctrine of the Church, in terms of its individual as well as corporate reference, see Moule, C. F. D., ‘The Individualism of the Fourth Gospel’, Nov. T. v (1962), 171–90.CrossRefGoogle Scholar See also Smalley, S. S., ‘Diversity and Development in John’, N.T.S. XVII (1970–1971), 282 f.Google Scholar

page 279 note 4 John iii. 13, al.

page 279 note 5 Cf. Smalley, S. S., ‘The Johannine Son of Man Sayings’, N.T.S. xv (1968–1969), 278–301, esp. pp. 299–301;Google Scholar but note the strong warning against accepting apocalyptic categories to interpret Son of man christology in the Gospels given by Leivestad, R., ‘Exit the Apocalyptic Son of Man’, N.T.S. XVIII (1971–1972), 243–67.Google Scholar See further E. Ruckstuhl, ‘Die johanneische Menschensohnforschung 1957–1969’, in Pfammatter, J. and Furger, F. (ed.), Theologische Berichte I (Zürich, 1972), 171–284.Google Scholar

page 280 note 1 In the prologue, as we have seen, the incarnation is the presupposition of all the signs.

page 281 note 1 The interesting study in the composition of the Fourth Gospel by Lindars, B., Behind the Fourth Gospel (London, 1971),Google Scholar for some reason takes no account of the epilogue.

page 281 note 2 Robinson, J. A. T., ‘The Use of the Fourth Gospel for Christology Today’, in Lindars, B. and Smalley, S. S. (ed.), Christ and Spirit in the New Testament (Cambridge, 1973), 64.Google Scholar

page 281 note 3 Meeks, W. A., ‘The Man from Heaven in Johannine Sectarianism’, J.B.L. XCI (1972), 44–72,Google Scholar argues that the ‘ascent–descent’ motif is central to the Fourth Gospel.

page 282 note 1 There is no reason to regard either John i or John xxi, because of their content, as compositions which have a fundamentally anti-docetic intention. See however R. Bultmann, op. cit. pp. 38–57 (Et, pp. 60–83), who regards the prologue as making use of the mythological language of gnosticism in order to refute gnostic misconceptions of the gospel. Bultmann supposes on the other hand that the meal in the epilogue (part of an ‘early Easter story’) is a replica of the Lord's Supper, in view of its ‘mysterious, cultic character’, and that it was included by the redactor out of a specifically ecclesiastical interest (Ibid. pp. 542–50; ET, pp. 700–11).

page 282 note 2 Cf. Bailey, J. A., The Traditions Common to the Gospels of Luke and John (Leiden, 1963), pp. 85–102.CrossRefGoogle Scholar Bailey draws out the points of contact between the Lucan and Johnniner resurrection narratives, and concludes that even if an independent, historical tradition lies behind parts of each, the fourth evangelist knew and used Luke in his writing. See also Talbert, C. H., ‘An Anti-Gnostic Tendency in Lucan Christology’, N.T.S. XIV (1967–1968), 259–71,Google Scholar suggesting that an anti-docetic intention coloured the resurrection narratives (inter alia) of the third Gospel. Note also John xx. 24–9, the touching of the risen Jesus by Thomas; Cf. Acts x. 41.

page 283 note 1 Cf. also John vii. 37–9.

page 283 note 2 Robinson, J. A. T., loc. cit. (see p. 281Google Scholar n. 2).

page 284 note 1 See, e.g., E. C. Hoskyns, op. cit. pp. 552–6; Barrett, C. K., The Gospel According to St John, p. 484;Google Scholar R. E. Brown, op. cit. II, 1074–6. Guilding, A., The Fourth Gospel and Jewish Worship (Oxford, 1960), pp. 226 f.Google Scholar, in line with her thesis that this Gospel was composed against the background of an ancient Jewish lectionary system, suggests unconvincingly that I Kings v, with its mention of the 153,000 (plus) labourers and officers (‘proselytes’, according to the parallel in II Chron. ii. 17) who were engaged in building Solomon's temple, lies behind the record of the number of fish in John xxi. 11.

page 284 note 2 Cf. inter alios Grant, R. M., ‘“One Hundred Fifty-Three Large Fish” (John 21: 11)’, H.T.R. XLII (1949), 273–5Google Scholar (mathematics); also Emerton, J. A., ‘The Hundred and Fifty-Three Fishes in John XXI. 11’, J.T.S. n.s. IX (1958), 86–9;Google Scholar followed by Ackroyd, P. R., ‘The 153 Fishes in John XXI. 11–A Futher Note’, J.T.S. n.s. x (1959), 94Google Scholar (gematria).

page 284 note 3 R. E. Brown, op. cit. II, 1076.

page 284 note 4 The chronology of John xxi. 1–14 appears awkward after xx. 19–29, since the disciples apparently return (disillusioned?) to work after meeting the risen Christ and being commissioned by him. It is possible that the traditions behind John xx and xxi were originally closer together chronologically; although John's placing of the sign in the epilogue now carries immense structural and theological weight.

page 284 note 5 Cf. Preiss, T., Life in Christ, (ET, London, 1954), pp. 9–31,Google Scholar who draws attention to the juridical setting of the Fourth Gospel, and its consequent insistence on the theme of witness.

page 285 note 1 ℵ Α Β W θ al. add a verse (from John xx) after Luke xxiv. 11, which includes a reference to the ‘linen cloths’ in the tomb.

page 285 note 2 But see Steinseifer, B., ‘Der Ort der Erscheinungen des Auferstandenen: Zur Frage alter galiläischer Ostertraditionen’, Z.N.W. LXII (1971), 232–65, esp. p. 264Google Scholar (John xxi. 1–14 cannot be appealed to as evidence that Galilee was the scene of the earliest resurrection appearances of Jesus).

page 286 note 1 On this whole section, see R. E. Brown, op. cit. II, 1094 f.

page 286 note 2 See Ibid. pp. 1087–9.

page 286 note 3 Of the five blocks of Petrine material unique to Matthew (in chapters xiv, xv, xvi, xvii and xviii), that involved in the confession (chapter xvi) is perthaps most open to the charge of unreliabilitym for obvious reasons. For a defence of its authenticity, see Cullmann, O., Petrus, Jünger-Apostel-Märtyrer: Das historische und das theologische Petrusproblem (Zürich, 1952), pp. 176–238;Google Scholar ET, Peter: Disciple, Apostle, Martyr (London, 1962 2), pp. 164–217.Google Scholar Cullmann argues that the original setting of the special matterial concerning Peter in Matthew xvi was the Last Supper (cf. Luke xxii. 31 f.

page 286 note 4 The appearance of the beloved disciple in John xxi. 1–14 need not be regarded as a redactional ‘addition’. John would have obvious reasons for referring explicitly to one of the other disciples already present in the tradition.

page 287 note 1 R. E. Brown, op. cit. II, 1089–1092, esp. p. 1091. R. Bultmann, op. cit. pp. 545 f. (ET, pp. 704 f.) claims that John xxi. 1–14 is a variant of Luke v. 1–11, and that John rectains the original context. However, in his Die Geschichte der synoptischen Tradition (Göttingen, 1957 3), p. 232Google Scholar (ET, The History of the Synoptic Tradition, Oxford, 1963, pp. 217 f.Google Scholar), Bultmann maintains that John's version is later and derives from Luke. See futher Delorme, J., ‘Luc v. 1–11: Analyse structurale et histoire de la rédaction’, N.T.S. XVIII (1971–1972), 331–50.Google Scholar

page 287 note 2 Sanders, J. N., A Commentary on the Gospel According to John, ed. Mastin, B. A. (London, 1968), pp. 449–51,Google Scholar believes that the narratives in Luke v and John xxi, rather than being edited versions of each other (because of their dissimilarities), draw on traditions derived from the same basic ‘meditation’ circulating in the early Church.

page 288 note 1 Fortna, R. T., The Gospel of Signs: a Reconstruction of the narrative Source underlying the Fourth Gospel (Cambridge, 1970), pp. 87–98.Google Scholar Fortna regards the catch of fish in John xxi as the third of the seven signs which made up the basic source used by John (p. 108).

page 288 note 2 Fuller, R. H., The Formation of the Resurrection Narratives (London, 1972), pp. 148–52.Google Scholar

page 288 note 3 Ibid. p. 131.

page 288 note 4 Ibid. pp. 151 f.