Introduction

Food-based dietary guidelines (FBDG) are directives developed by countries to define recommendations for healthy eating(1). These guidelines should be formulated based on the social, economic, cultural and epidemiological characteristics of each country, and, therefore, be developed locally(2). They require to be updated periodically based on the changes in population health demands and new scientific evidence regarding the relationship between food, nutrition and health(1).

The current food system did not ensure adequate, healthy and affordable food availability. Currently, poor diet is one of the major global causes of low quality of life and early mortality. It is estimated that about 11·6 million early deaths could be prevented with improvement in diet quality, which includes one-third of the total deaths due to CHD(Reference Wang, Li and Afshin3). The growing consumption of ultra-processed foods is a risk factor for the increased prevalence and incidence of obesity, diabetes, hypertension and other chronic diseases(Reference Pagliai, Dinu and Madarena4,Reference Askari, Heshmati and Shahinfar5) . In addition to direct health effects, the food system is an important driver of climate changes and biodiversity loss(Reference Willett, Rockström and Loken6).

Hence, national FBDG that assume expanded paradigms of healthy eating gain relevance in recognising the determinants of the food system that impact the human and planetary health(7–Reference Fischer and Garnett10). However, their potential to promote healthy and sustainable diets would be incipient if the recommendations are not implemented effectively. Their implementation requires national intersectoral coordination to communicate recommendations and foster public policies(11).

Brazil was one of the first countries to take a broad approach to healthy eating, including environmental, economic and sociocultural sustainability as guiding principles for the second edition of its FBDG—called dietary guidelines for the Brazilian population (DGBP), launched in 2014(Reference Monteiro, Cannon and Moubarac12,Reference da Oliveira and Silva-Amparo13) . Another novelty of the DGBP was the adoption of a food classification based on the extent and purpose of processing (NOVA classification), recognising the negative effects of the production and consumption of ultra-processed foods on health and the environment(Reference Monteiro, Cannon and Moubarac12–Reference Bortolini, Moura and Lima14).

Following publication, several intersectoral measures were employed to implement the new recommendations; however, no study has analysed them to identify gaps and potential. A theoretical framework that guides the implementation of FBDG could facilitate an analysis; however, to the best of our knowledge, no such framework has been published. Therefore, this study aimed to develop a conceptual framework of the process of FDBG implementation and analyse Brazil’s employed measures to implement DGBP (2014).

Methodology

Construction of the conceptual framework

A conceptual framework of FBDG implementation was constructed using the qualitative method proposed by Jabareen(Reference Jabareen15). According to this author, conceptual frameworks are ‘networks of interlinked concepts that together provide a comprehensive understanding of a phenomenon or phenomena’, in this case the FBDG implementation. This method is based on the extensive search and analysis of a theoretical body in which concepts are identified and derived, allowing the deduction of interconnections between them(Reference Jabareen15). The required steps are the selection of the data sources; the extensive reading and categorisation of the material aiming at identifying concepts and integration and synthesis of the concepts into a conceptual framework(Reference Jabareen15).

As data sources, both materials scoped within the macropolitical sphere and scientific articles were selected. Regarding the first one, publications from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN (FAO) — the FBDG’ international body — were analysed, including technical documents(1,Reference Fischer and Garnett10,11,16–19) and videos from a webinar cycle(20). A scientific literature review was conducted for articles related to FDBG implementation, published between 1996 (FAO year of publication, establishing FBDG) and May 2020. The search was conducted in English and Portuguese using the terms ‘food-based dietary guidelines’ or ‘dietary guidelines’ and ‘implementation’ or ‘promotion’ or ‘dissemination’ or ‘communication’. Studies describing experiences or discussing theoretical aspects of FDBG implementation applicable to different contexts were included.

The FAO’s materials were used to identify the main inductive themes regarding FBDG implementation; this worked as a basis to the reading and analysis of the scientific articles. Besides the identification and categorisation of the FAO’s priori themes, emerging themes were also identified in the articles. The data source was analysed by two researchers (KTG and CRT). From these themes, concepts were derived and interconnections between them were deducted and synthesised.

Identifying actions developed in Brazil

To identify Brazil’s measures for DGPB implementation, we focussed on the actions carried out by the public authority within the National government, as it is the body responsible for these guidelines’ preparation. The DGBP constitutes the intersectoral agenda for promoting adequate and healthy eating instituted by the National Food and Nutrition Security System(21) and managed through the National Plan for Food and Nutrition Security, which should be updated every 4 years regarding budget targets and responsibility delegation for different sectors(22). DGBP’s revision was one of National Plan for Food and Nutrition Security’s goals for the 2011–2014 period, while its implementation was one of the goals for the 2015–2019 period. According to this plan, the implementing bodies of DGBP were the Ministries of Health, Education and Social Development (current Ministry of Citizenship)(23). We identified the implementation measures of these sectors based on institutional websites and technical management reports.

Results

Conceptual framework

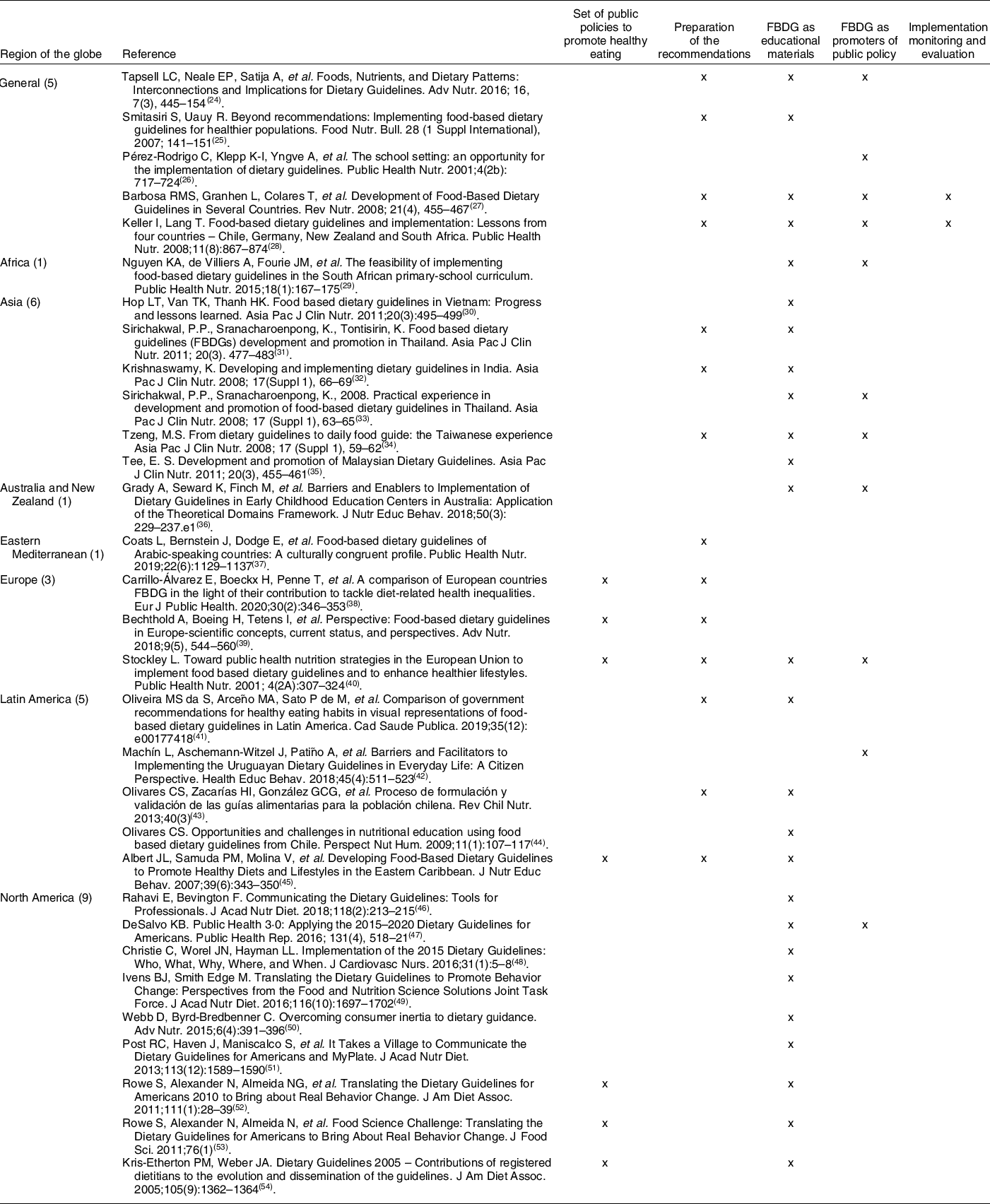

FAO directs three types of implementations of FBDG including the preparation of viable, understandable and culturally referenced recommendations; FBDG as educational materials and promoting FBDG through public policies. Thirty-one scientific articles were included, of which 6 discussed theoretical aspects applicable to different contexts and 25 described experiences of implementing FBDG in a specific country or region. Of these, the following themes emerged: a set of healthy-eating public policies; the development of an integrated implementation plan and monitoring and evaluation of the implementation. Table 1 presents the articles and the themes addressed by them divided according to the region of the globe.

Table 1 Selected articles by the framework themes and the globe regions

FBDG, food-based dietary guidelines.

The themes conceptualisation is described below:

Set of public policies to promote healthy eating

A broad set of intersectoral policies to promote healthy eating facilitate the implementation of FBDG in any country; they must facilitate the dissemination of new recommendations, enhance the educational function of FBDG and influence pre-existing and future public policies.

Implementing FBDG

The FBDG’ implementation process is composed of four steps: preparation of appropriate recommendations; implementation planning; plan execution and monitoring and evaluation. The entire process should be led by the government sector responsible for the FBDG in each country (e.g. ministries of health or agriculture), which must create mechanisms to engage and commit other sectors related to food, health and well-being and sustainability policies, as well as multiple stakeholders in all the steps. The involvement of not only other government sectors but also representatives from civil society, academy and private sector are one of the underpinnings of the implementation success.

Preparation of viable, understandable and culturally referenced recommendations

To facilitate implementation, it is important to establish recommendations based on food and not nutrients, reinforcing the main purpose of FBDG. In addition, the predominant approach that groups foods according to nutrient profile and formulate recommendations, such as that established in the ‘food pyramid’, has been considered limited to explain the complexity of the relationship between diet and health, since it ignores the interaction between both food components and foods combinations. Recommendations based on local foods and food patterns are not only more understandable and viable but also establish a cultural bond with the population. Moreover, they must target different population subgroups; multiple stakeholders should be involved in the preparation process. The recommendations should be presented in accessible language and/or communicated through visual icons (food guides).

Development of an integrated implementation plan

Along with the preparation of recommendations, it is important to create an integrated implementation plan before publication. This plan should define the objectives, goals, indicators (short and long term), resource allocation and effective and sustained participation of various political and social stakeholders.

Executing the implementation plan

The FBDG are implemented in two major ways: (a) as educational materials and (b) as promoters of public policies. The two approaches may overlap and produce a synergistic effect.

-

(a) FBDG as educational materials: The most common means of FBDG dissemination are the production and distribution of educational materials, and training of facilitators. Short-term strategies, such as a wide release and distribution of copies; medium-term strategies — such as the preparation of educational materials of different types — (folders, booklets, videos, etc.) or long-term strategies — such as the training of facilitators from different sectors and stimulation by the continued use of educational materials — can be considered.

-

(b) FBDG as promoters of public policy: FBDG can promote public policies regarding agricultural policies, education and social assistance, among others. Some strategies for FBDG implementation through public policies are: creating links with established policies, such as school feeding menus; food quality improvement via reformulation policies; advance regulatory agenda, such as regulating food advertising, establishing appropriate labelling, taxing sweetened beverages, among others and guide the development of national strategies for training professionals and facilitators.

The two means can be combined, and educational strategies can be implemented in the form of public policies, especially long-term ones. In a synergistic relationship, educational materials can influence the demand for public policies, since the appropriation of recommendations by the population awakens the need to overcome systemic obstacles; conversely, public policies might facilitate their communication. Finally, these measures’ effectiveness can only be enhanced if implemented on priority target audiences, such as schools, health services and strategic contexts.

Implementation monitoring and evaluation

This step concerns the monitoring of implementation process indicators listed in the plan, which can indicate critical points of the implementation, and the impact of recommendations on the diet of the population—useful to indicate the relevance and potentially updating the recommendations themselves. This step is of paramount importance so that it is possible to analyse and understand where, what and why impacts were or were not found.

The conceptual framework illustrating the interconnections established between these concepts is presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1 Conceptual framework for Food-Based dietary guidelines implementation

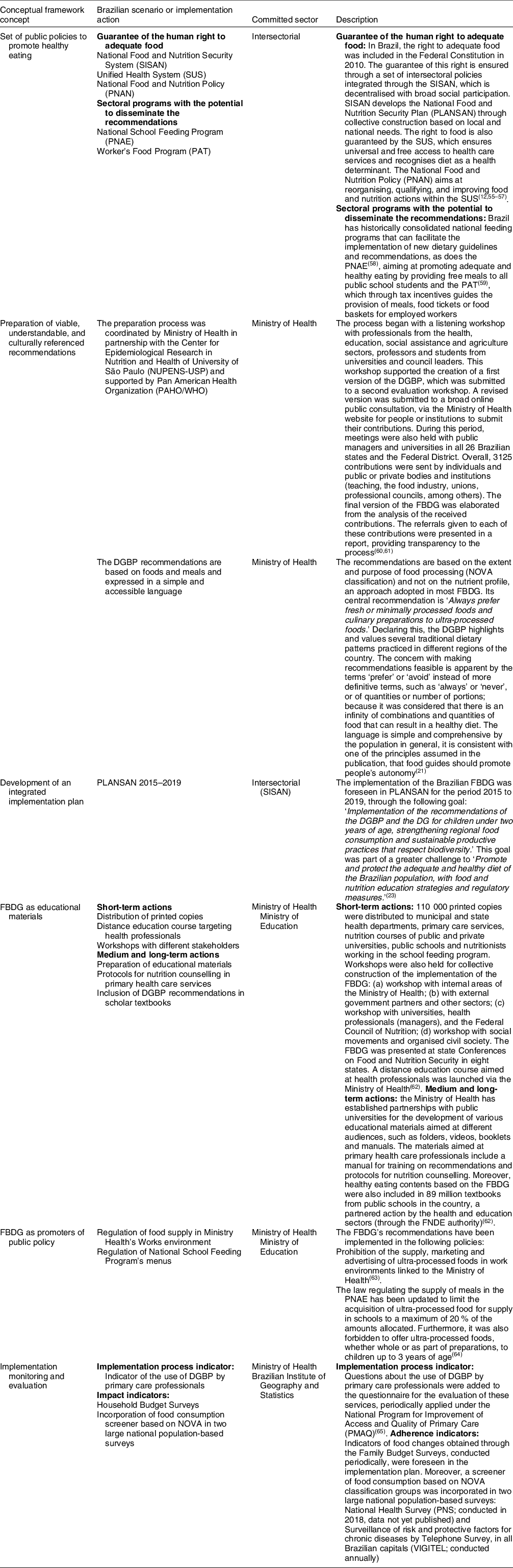

Actions performed in Brazil

Table 2 describes the characteristics of the DGBP—and Brazil’s measures—according to the conceptual framework. Brazil has a range of policies that promote healthy eating, guided by the principle that food is a right. An implementation plan was created; however, most of the implemented measures focussed on the concept of ‘FBDG as educational materials;’ although, the recommendations have also been implemented in public policies.

Table 2 Scenario or implementation action of the dietary guidelines for the Brazilian population (DGBP) (2014), according to the conceptual framework

FBDG, food-based dietary guidelines.

Discussion

A conceptual framework was developed to implement FBDG, keeping the materials published by FAO as theoretical references, in addition to scientific articles. Although the field of public health nutrition has been discussing conceptual frameworks for the nutrition science implementation, as far as we know, none has proposed a conceptual framework for specific implementation of FBDG(Reference Tumilowicz, Ruel and Pelto66,Reference Sarma, D’este and Ahmed67) . Adopted as a study case of the proposed model, the detailed process adopted in Brazil in each of the steps were analysed and described.

Given their instructive nature, several authors highlight the importance of FBDG as a broad national strategy for the promotion of healthy eating, with the commitment of several sectors(Reference Fischer and Garnett10,Reference Smitasiri and Uauy25,Reference Keller and Lang28,Reference Hop, Van and Thanh30,Reference Bechthold, Boeing and Tetens39,Reference Stockley40,Reference Machín, Aschemann-Witzel and Patiño42,Reference Olivares, Zacarías and González43,Reference Mozaffarian, Angell and Lang68) . According to Tumilowicz(Reference Tumilowicz, Ruel and Pelto66), successful implementation requires a culture of inquiry, evaluation, learning and response among implementers; an action-oriented mission among the research partners; continuity of funding for implementation research and resolving inherent tensions between program implementation, research and society sectors. The literature review showed that some regional frameworks recommend countries to build their own integrated and broad national food and nutrition policy, from which FBDG must be part(Reference Bechthold, Boeing and Tetens39,Reference Stockley40) .

Although the importance of FBDG implementation strategies being linked to plans, programs and public policies in an intersectoral way, this link is not explicit for most countries(Reference Olivares, Zacarías and González43). This gap decreases the potential for disseminating the recommendations, in addition to weakening the link with specific policy interventions and becoming vulnerable to the influence of specific interest groups(11). An exception on this regard is the USA, which clearly and systematically adopts the Dietary Guidelines for American as the basis for all food policies in the country (school, hospital, military, etc). In Brazil, although the link was not previously explicit, the existence of a previous set of policies to promote healthy eating was important in all stages of the implementation of the DGBP.

Some Brazilian’s legal frameworks operated as a driving force for the paradigm shift in the concept of healthy eating, which was consolidated in the recommendations. Namely, the Organic Law on Food and Nutrition Security of 2006 was the first to integrate health promotion, cultural diversity and environmental, cultural, economic and social sustainability in a single concept. National Food and Nutrition Security System, an intersectoral policy integrator system, was created through LOSAN to ensure multi-dimensional food and nutrition security(69). Furthermore, in 2010, the human right to adequate food was included in the federal constitution(55) and the State was imposed with a duty to guarantee this right.

Regarding FBDG’s preparation, the participation of different public sectors (such as health, education, agriculture, etc) and representatives of civil society, academia and private sector contribute to recommendations’ consistency, viability and popular comprehension(1,Reference Tee35,Reference Coats, Bernstein and Dodge37) . However, some authors argue that the economic power and potential conflicts of interest linked to the private sector participation must be acknowledged(Reference Fischer and Garnett10,Reference Sirichakwal, Sranacharoenpong and Tontisirin31,Reference Olivares, Zacarías and González43) . Accordingly, their participation must be conditioned by clear rules established by public authorities, determining their limits(Reference Fischer and Garnett10,Reference Mozaffarian, Angell and Lang68) . The DGBP preparation was internationally recognised, as multiple stakeholders participated and its conduct was transparent(Reference Fischer and Garnett10,11) .

In DGBP’s public consultation, representatives of the food industry adopted a strong opposition to the NOVA classification, denying the environmental impact of the food system, and defending individual freedom(Reference Davies, Moubarac and Medeiros70). This reaction is consistent with the fact that the DGBP identifies the hegemonic nature of the food system, which is dominated precisely by the private sector, as the root cause of a poor diet(Reference Davies, Moubarac and Medeiros70). The analysis of these contributions by the Ministry of Health was guided by principles that facilitated the entire creation of the recommendations, defined mainly within the expanded concept of healthy eating and the human right to adequate food.

Despite the resistance, adopting the NOVA classification has been shown increasingly benefit not only to the epidemiological point of view—considering the growing body of evidence regarding the association between ultra-processed food consumption and poor health outcomes—but also to the food culture perspective—since it isolates this food group, which tends to replace traditional foods(Reference da Oliveira and Silva-Amparo13,Reference Louzada, Canella and Jaime71) . By recommending that fresh and minimally processed foods constitute a diet’s basis, the DGBP provides examples of traditional meals consumed in various regions of the country(21). Therefore, NOVA is an appropriate tool to guide the recommendations based on dietary patterns that reflect the local characteristics(Reference Tapsell, Neale and Satija24).

Brazil did not create an icon to communicate the recommendations, which is justified both by NOVA’s adoption and renunciation of the indication of quantities or portions’ numbers. Although widely adopted by several countries(Reference Herforth, Arimond and Álvarez-Sánchez72), there seems to be no consensus in the literature regarding the contribution of icons to better communicate recommendations. According to Coats et al. (Reference Barbosa, Granhen and Colares27), the elaboration of icons which include culturally recognised elements can facilitate the creation of a first sociocultural tie with the population. However, Oliveira et al. (Reference da Oliveira, Arceño and de Sato41) point out that icons tend to summarise the diversity of dietary practices in a single national identity, potentially resulting in negligence of certain forms of knowledge and culturally established practices in some specific groups of the population.

The conceptual framework highlights the importance of a widespread dissemination of educational materials and public policies(17). In Brazil, a wide diversity of educational materials — such as videos, folders and a pocket version— aimed at different audiences and contexts, such as primary health care services, schools and the general population was elaborated through agreements between the Ministry of Health and public teaching and research institutions.

The predominance of educational measures over the promotion of public policies can be explained by the fact that the paradigm shift introduced by the DGBP required broad dissemination of recommendations. Furthermore, the role of FBDG as educational materials has been stimulated by FAO since they were proposed in 1998(1), unlike the promotion of public policies, which began to gain prominence only in more recent publications(Reference Fischer and Garnett10,11,16) . According to a report published in 2016, most countries have not established public policies for FBDG yet(11).

Moreover, educational measures are easier to implement when compared to promotion or reformulation of public policies, since they tend to be less susceptible to private groups’ lobbying(11). However, public policies, although less numerous in the Brazilian case, have a higher potential impact. Aligning the national school feeding program with the DGBP recommendations, for instance, can potentially reach more than 40 million 74 people daily, corresponding to approximately 1/5 of the Brazilian population.

The literature reviews found that many countries spent significant efforts on the development of FBDG but did not draw up evaluation plans(11). Some countries conducted partial assessments through population-based food consumption surveys; however, these questionnaires could not ascertain what dietary changes could be attributed to the FBDG(11).

Only impact indicators were foreseen in the DGBP implementation plan, which is related to the strong Brazilian tradition with national surveys. The last report (2017–2018) of the Household Budget Survey shows that after the publication of the DGBP, there was a slowdown in the increasing trend of the share of ultra-processed foods in the total household food purchase(73). This indicator reveals DGBP’s potential impact in resisting the growing market expansion of ultra-processed products in developing countries(Reference Vandevijvere, Jaacks and Monteiro74). NOVA-based food consumption screeners have also been included in recent editions of other population-based surveys; however, these cannot be compared to periods preceding DGBP’s publication.

Although not foreseen in the implementation plan, in its last edition (2018), another traditional survey evaluating primary health care services in Brazil included questions regarding DGPB use by health professionals in their professional practices(65). About 85 % of the multidisciplinary teams of primary care reported their use of the DGBP.(65) Although this new indicator cannot be compared with other periods, it is a relevant process indicator, since several DGBP implementational efforts targeted the primary health care. Furthermore, it is also important since 60 % of Brazilian’s households are registered in the Family Health Strategy (national primary health care strategy), which is a wide coverage(75).

One limitation of the Brazilian implementation analysis in this study is the exclusion of measures carried out by local authorities (states and municipalities). Regarding public policies, for example, one Brazilian state regulated the supply of food in canteens of public and private schools based on the DGBP. Spontaneous initiatives from other public or private institutions, such as professional councils or universities, and media influencers which play an important role, were also not included. Although our method could not reveal the exact extent of implementation throughout Brazil, it highlighted the National government’s role, which is the main body responsible for implementing and inducing local measures.

Although educational actions have predominated, the DGBP’s recommendations were included in the National School Feeding Program, the largest national food program. Beyond that, both educational and policy measures worked in a complementary way, optimising the implementation of the recommendations in key contexts, such as education and health services. However, it was noted that the absence of sectors such as Ministries of Agriculture and the Environment, whose commitment in the implementation would be essential to consolidate the recommendations related to environmental sustainability. In addition to promoting greater intersectoral cooperation, it is also important to adopt process indicators already in the implementation plan.

The DGBP is recognised as one of the emblematic examples of a virtuous cycle of progressively ensuring the human right to adequate food, which has been underway in Brazil for more than two decades. However, the advances in the public health nutrition agenda observed during that period have been threatened for the last years due to a political crisis that results in President Dilma Rouseff impeachment and the election of a conservative and neoliberal president. As one of his first government measures, at the beginning of 2019, the President Jair Bolsonaro extinguished the National Council of Food and Nutritional Security, which meant a great loss for National Food and Nutrition Security System, since National Council of Food and Nutritional Security was responsible for bringing society’s priorities on food and nutritional security to the government agenda(Reference Castro76).

Besides, in 2020, the DGBP was directly attacked through a technical note from the Ministry of Agriculture addressed to the Ministry of Health calling for an urgent revision. The document claimed especially to a change in the recommendation to avoid ultra-processed foods, ignoring the strong evidence of its association with obesity and many chronic diseases. The energic reaction of the civil society and institutions from the nutrition field, as well as the visible poor technical quality of the technical note, forced a retreat from the Ministry of Agriculture(Reference Monteiro and Jaime77).

Both episodes experienced in Brazil point that even in country with a strong public health system and well established food and nutrition public health policies, the consolidation of a FBDG is not immune to the political context, which reinforces the importance of strong democracies to guaranteeing the human right to adequate food. Further research could analyse the impact of that on the effectiveness of the implementation measures.

In sum, the implementation of the Brazilian FBDG presented advances in all elements of the conceptual framework. The main enablers in the process were both the pre-existent background of public health and healthy-eating policies and the engagement of different stakeholders through all the process—namely, government, civil society and academy. On the other hand, the barriers were the lack of commitment of some sectors and political inertia and discontinuity of politics with the change of government.

This analysis showed that the conceptual framework suited well to the Brazilian case. The analysis of other countries’ employed measures using this framework could not only bring other possible enablers and barriers of FBDG implementation but also improve this proposed conceptual framework.

The novelty of this study is the proposal of a conceptual framework, which can guide the elaboration of plans and analyses of the process of FBDG implementation by other countries and enables comparative analyses. This model frames FBDG implementation as part of a larger set of intersectoral public policies to promote healthy eating, which is significant, given these documents’ importance as promoters of healthy and sustainable food systems(Reference Willett, Rockström and Loken6–Reference Ridgway, Baker and Woods9).

Further, it also equates the importance of educational measures and promotion of public policies, expanding the historically predominant sense that FBDG help to communicate recommendations on healthy eating. The role of FBDG as promoters of healthy and sustainable food systems must necessarily consider that implementation is carried out in an integrated manner, with multiple actions and with commitment to multiple sectors.

National experiences in FBDG implementation are little documented in the academic literature, and the existence of national implementation plans is fragile worldwide. The Brazilian’s case analysis can be helpful to decision makers in food policy across the globe be inspired by the Brazilian efforts, considering that the Brazilian guide was one of the firsts to has adopted a multidimensional paradigm of healthy eating, including diet sustainability.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: None. Financial support: KTG received scholarship from São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) (process number 2019/01206-8) and from Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) (from November 2018 to July 2019, process number 169281/2018-3). FAPESP and CNPq had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this manuscript. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: K.T.G.: Conceptualisation, Methodology, Investigation, Writing — Original Draft preparation; C.R.T: Methodology, Investigation, Writing — Review & Editing; P. C. J: Conceptualisation, Methodology, Writing — Reviewing and Editing, Supervision. Ethics of human subject participation: This research does not involve human participants.