In a famous preface to the first issue of the Illustrated London News in 1842, the editors state that the new publication will, with the help of words and pictures, bring to the public “the very form and presence of events as they transpire.”Footnote 1 At least since the publication of Mason Jackson's survey The Pictorial Press, Its Origin and Progress (1885), this quote has been used to characterize the truth claims of the early illustrated newsmagazines.Footnote 2 This, and other similar statements used in advertising the new illustrated papers, suggests that the ideal of early illustrated news was both contemporaneity (“as they transpire”) and a naïve form of unmediated representation (“the very form and presence of events”): “Illustrated news promised the sort of picture that one would have come away with had one actually been at the event.”Footnote 3

Historical studies of the mid-nineteenth-century illustrated press in Europe—with such well-known publications as the Illustrated London News, L'Illustration, and the Illustrirte Zeitung—have of course thoroughly problematized this “discourse of objectivity” and criticized all claims to achieve “unmediated presentation of the world as it empirically exists” by showing just how farfetched such ideas about direct visual access to the real actually were, not least because of the lack of firsthand information.Footnote 4 In addition to this, several recent studies have also taken the analysis further by focusing on how reality effects could, nonetheless, be achieved at the time. These studies have put questions about how actual news images convinced and attracted their audience at center stage, rather than general statements about the purpose of illustrated news. Instead of discussing whether the images published were actually “a truthful mirror” of nature, they have returned to the images in order to describe how they worked in the context of the magazines as print media.Footnote 5

Scholars like Ulrich Keller, Tom Gretton, Andrea Korda, and Rachel Teukolsky have all provided important perspectives on visual realism and how early wood-engraved news images functioned.Footnote 6 The following analysis will build on their work, and I will come back to specific contributions later, but there are also certain limitations to this literature—in particular because discussions have mostly been confined to subjects such as wars and uprisings, social problems, violent crimes, and accidents.Footnote 7 This is in many cases well motivated; there was certainly an interest already in early pictorial journalism for dramatic events and socially engaged subjects. But a focus on such topics, which often foreshadow what later came to be the staple of modern pictorial journalism and photo reportage, also gives an undue weight to certain types of images and in many cases, though not all, to the eyewitness account as a journalistic practice. Especially when the development of the on-the-spot sketch is described as the most important invention of illustrated news—epitomized in Baudelaire's famous praise for the drawings of Constantine Guys and their ability to capture the fleeting moment of modernity—other images that were crucially important during the early years of illustrated news, and the often rather different codes of truthfulness they followed, tend to be marginalized.Footnote 8

An example of this tendency to overlook images that don't quite conform to later notions of the newsworthy is the comparative lack of interest shown images of ceremonies and staged public events, especially the many political and civic gatherings involving spectators and audiences that were everywhere in illustrated magazines during the early, formative years of illustrated news in Europe. Such images represented inaugurations, political rallies and meetings, visits by dignitaries, parades, popular festivities, public dinners, etc. Since the late nineteenth century there has often been a tendency to regard topics of this kind as part of a rather pompous and outmoded bourgeois public culture and instead focus on other images—or often the lack of them—that more resemble later notions of what pictorial journalism should be about.Footnote 9 A shift toward the reporting of live events, as opposed to such staged occasions, has even been described as an integral part of the creation, during the second half of the century, of a “true illustrated journalism, based on reportage.”Footnote 10 However, I would argue that if we want to understand how the average news image functioned, it is also crucial to include this type of imagery, ordinary and often bland but also an important aesthetic form in its own right. Even though the repetitiveness of such images has often been seen as something that makes them uninteresting, they can give access to an alternative history of how illustrated newsmagazines conveyed information and question assumptions about the role of firsthand observation as the primary source of truthfulness.

In the following I will discuss a number of examples, selected from the total corpus of images of ceremonies and staged public events published during the 1840s, because they are representative of important general tendencies and relate specific features of their visual rhetoric to broader aspects of mid-nineteenth-century visual culture. The examples chosen are mostly of political gatherings, primarily since such events played an important role in the illustrated press but also because interesting features are easier to observe in contexts where there is a clear agenda. Examples are taken from the most important illustrated newsmagazines during the period: the Illustrated London News and the Pictorial Times in London, L'Illustration in Paris, and the Illustrirte Zeitung in Leipzig.Footnote 11 Magazines from different European countries are included because the aim is to locate common features and images also circulated widely across borders during these years. All the magazines were aimed at similar middle-class audiences and often stood for a rather complacent form of political radicalism focused on national unity and universal progress, but at the same time, each magazine also had its own editorial policy related to national politics. Such differences, however, will only occasionally be highlighted; what is most important in this context is that they used similar aesthetic means to communicate.

The analysis will show how the new mass medium recycled and developed a number of specific pictorial conventions. More precisely, I will argue that these magazines established a new idiom for pictorial reportage that can be described as synoptic, in the sense of affording a general view of a whole or bringing together different elements to summarize a story.Footnote 12 As this type of imagery shows, the illustrated newsmagazines—in addition to eyewitness accounts from a specific, real-world viewpoint—also developed other pictorial means to condense events based on many different kinds of information (observations, texts, rumors), a visual language that also permitted, without apparent contradiction, the use of allegory and other nonrepresentational elements to create expressive effects and enhance the main points. How this worked can be seen if we focus on how images were related to a market for news in which information circulated at different speeds and in different formats, if news images are treated as visual adaptations in one medium of information from other media, adaptations that were closely related to the specific affordances of the weekly illustrated magazines as periodicals. Rather than more or less successful renderings of observation only, it is revealing to approach them as attempts to take information in one medium (whether oral accounts, printed or written texts, drawings or sketches) and accurately translate it into another “more vivid, visual, physically present medium,” that is as a form of “realization” in the sense of Martin Meisel.Footnote 13

If early news images are approached from this angle, it becomes apparent that their relation to pictorial truth was sometimes different from what has been assumed, but arguably also that their contribution to modern news time was more complex. It is easy to think of news as an ephemeral product that conveys rapid information about the passing moment; the flow of information in modern news media typically creates a sense of immediacy based on rapid access to information, and the role of imagery in this context is to convey fast glimpses of events as they unfold. This “time of the now,” with an ever-changing present consisting of rapidly produced and consumed bits of information, is often seen as a fundamental part of modern news time.Footnote 14 Accordingly, the rise of illustrated newsmagazines in the middle of the nineteenth century has often been assumed to have almost exclusively contributed to a temporality of this kind; the focus has often been on the role of the illustrated magazines in speeding up the flow of visual information about newsworthy events with the help of industrialized production processes.

But rather than only speeding up the communication of information, the type of synoptic images to be discussed here also slowed it down and focused the attention of the audience on specific events. I will argue that this type of news illustration often functioned as a form of “visual history” in the sense recently outlined by Daniela Bleichmar and Vanessa Schwartz: its role was to archive or make lasting “something in the present or near past that [was] expected to become of historical significance at some point in the future,” and it was thus in many ways the opposite of something ephemeral to be looked at distractedly.Footnote 15 This archival tendency was at work at the level of the magazine but also in the images themselves: as synoptic, the images condensed and summarized information and thus became “histories” in the sense of stories, but they also actively related the scenes depicted to earlier events and in this way “historicized” occurrences by inserting them into larger narratives.

How synoptic and archival tendencies were tied together will be described in more detail below. Taking as my point of departure previous research on the nineteenth-century illustrated press, and especially the role of the eyewitness, I will first focus on how the images conveyed information. In the second part of the article, I then discuss the archival function of illustrated magazines and analyze three strategies used to establish connections between current events and historical contexts. In a final section, I summarize the argument and contend that this type of imagery seems to have contributed to a modern sense of history as an accelerating process, but in a different way than has often been assumed.

1. News Images and the Role of the Eyewitness

Most accounts of the birth of illustrated news focus on how the development of wood engraving made new ways of printing image and text together possible during the first half of the nineteenth century.Footnote 16 Generally, they begin with the revival of wood engraving by Thomas Bewick and his pupils at the turn of the nineteenth century and how they pioneered a new way of engraving the end grain of boxwood with burins, a technique that made it possible to produce images of greater detail and finer gradations of light and shade than in the traditional European woodcut. This procedure was first used by Bewick in illustrating books of natural history but was also soon to be used in the press to depict current events. Newspapers like the Observer in London and the New York Herald, which occasionally published wood engravings already during the 1820s and 1830s, are often mentioned as early examples. Another important development was the use of wood engravings to spread useful knowledge to popular audiences in cheap illustrated periodicals, with the Penny Magazine published in London as the great forerunner, but the practice was soon to be found in many countries. These developments were then continued by the well-known European illustrated weeklies launched during the 1840s, which visualized events on a regular basis for more affluent, middle-class audiences. Even though these magazines were in many ways miscellaneous publications that contained different kinds of imagery, the focus on current events makes it easy to see this as the real birth of the news image, at least as a regular phenomenon.

Many general accounts of the development of the illustrated press stress the increasing speed of production made possible by the new techniques of wood engraving, together with the development of cheaper paper based on wood pulp and the steam press, as well as the possibilities opened up, both artistically and in terms of production efficiency, by the ability to integrate wood engravings with type in the printing processes. This focus on the development of new technical possibilities often leads to a narrative of the news image that privileges aspects such as speed in production and volume in printing, and the early news image is here inscribed in a history of modern news culture that was based on the reporting and substitution of information in an ever-increasing pace; their value is seen as closely related to speed: ephemeral products in a nascent consumer culture.

As already noted in the introduction, this fast flow of information has also been connected to a discourse of objectivity. The modern conception of visual news has been described as based on two promises to the reader: the “promise of contemporaneity,” which entails that events should be depicted when they are “hot,” and a “promise that could be called ‘naturalistic,’ which entails saying and showing the truth from nature.”Footnote 17 In this the role of the eyewitness has often been described as playing a crucial part, and especially the development of the role of the “Special Artist” who traveled to the site of newsworthy events, like wars and uprisings, to sketch the action as it unfolded.Footnote 18 Not least, the importance of this development has been underlined in studies that focus on the many problems encountered by the early illustrated magazines, before they had the real means to obtain on-site observations.Footnote 19

As underlined in these studies, claims to present readers with direct visual access to events was surely an important part of a discourse of objectivity associated with the illustrated magazines, especially later during the 1850s when the notion of the special artist had become fully developed, as we can also see from references in news articles and captions to on-site observation. However, as researchers such as Tom Gretton and Ulrich Keller have clearly shown, artistic interpretation based on established compositional and expressive codes was also an integral and accepted part of documentary image-making at the time, and it is best to avoid neat distinctions between “Art” and “journalism” even though empirical observation became increasingly important.Footnote 20 There is much to suggest that what was actually at work in many early news images was a notion of how to faithfully represent the real that made any clear-cut distinction between on-site documentation and later reconstruction too simplistic. At the time, there was simply no fundamental separation between “eyewitness observation” and “interpretive historical accounts,” as Keller puts it.Footnote 21

Furthermore, many (perhaps most) documentary images published during the early years of illustrated news were not described as the result of direct observation or attributed to specific correspondents, yet their information value seems to have been accepted nonetheless. In practice, there also seems to have been other criteria at work than eyewitness authenticity, and pictorial truth as the visual presentation of a specific moment in time from a real-world viewpoint was clearly not the only idea in circulation. The dominance of such notions is rather a later product of new standards associated with press photography and a new kind of “mechanical objectivity” in the sciences.Footnote 22 As Rachel Teukolsky has argued in a recent study of how reality effects were achieved in war pictures during the 1850s, there was rather a multiplicity of ways to achieve realism. For example, she distinguishes between “the descriptive,” focused on indexical truth and the reproduction of details and surface appearances; “the authentic,” based on the representation of experiences of participants at the scene of events; “the everyday,” where realism is indicated by a focus on ordinary characters or low-status subject matter; and, finally, “the plausible,” where a sense of truthfulness is achieved by the use of recognizable types and conventional signs.Footnote 23 This might not be the only way to classify different approaches to truth or realism at the time, but this analysis at least clearly shows that different pictorial strategies were operative in early news images.

An important point emerges from this brief summary of perspectives in earlier research: eyewitness accounts surely became increasingly important in illustrated weeklies focused on current events, but it should not be assumed that the most relevant question about the truthfulness of news images was always whether they were based on what an artist had observed at the spot; there were also other criteria at work. To this can be added that the easily observable and very common dependence on textual or oral reports in the making of news images should perhaps be understood less as a lack than as a condition of image production that was taken for granted and entailed its own specific challenges. In a situation where such intermedial relations were often unavoidable, criterions of truthfulness would not primarily have focused on whether the images always gave an accurate real-world view of specific moments, but rather whether they adapted textual or other available information in acceptable ways. It is thus necessary to look for the means of such translations of information into news images and their connections to the broader visual culture of the time, its aesthetic conventions and popular modes of expression.

2. Condensations, or Images as Summary Statements

That different strategies were used to create succinct, legible, and believable images in mid-nineteenth-century news illustration can be seen in the representations of ceremonies and staged public events that often dominated the early illustrated weeklies. An overview of how images of such gatherings conveyed information will show this. The following examples have been chosen because they clearly demonstrate different pictorial strategies, but they are otherwise highly typical and comparable to a large number of similar depictions of public events. For the sake of clarity, I will mostly discuss individual images, but in conclusion will also briefly touch upon the important effects of seriality.

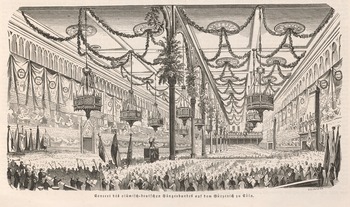

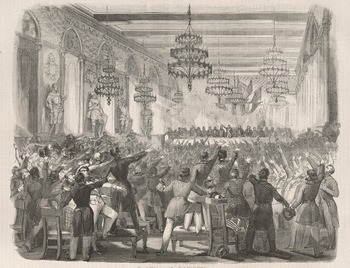

The first example shows a concert by the German-Flemish singing society in Cologne in 1846 (fig. 1). That this concert was considered an important and even imposing event is apparent from the image itself as well as the accompanying text published in the Illustrirte Zeitung, which celebrated the patriotic meaning of this meeting of “kinsmen.”Footnote 24 This representation of a public gathering clearly focuses on the whole, the totality of the people and the surrounding architecture. The use of a systematically executed one-point perspective, and especially the long row of lamps and columns that vanishes into the distance, creates a depth in the picture that enhances the size of the crowd, the sense of the hall as a vast space, etc. That the mass of people is represented as an indistinguishable sea of heads fits nicely with the general purpose of the event, which was one of fraternization, to the point of trying to assimilate the Flemish into an overarching German nationality.Footnote 25 At the same time the image also shows details of specific kinds: the dress of the participants in the foreground, decorations on the walls and the ceiling. In a typical manner, the people in the foreground are positioned at a distance into the picture but are still outlined in some detail and in darker tones, while the rest of the crowd is mostly indicated by a network of undulating or straight lines printed in the middle of white areas.

Figure 1. Illustrirte Zeitung 7 (1846): 89.

The detailed description of architecture here serves to localize the action and provide the image with an indexical—or descriptive, as Rachel Teukolsky would have it—quality that was clearly important for how it was apprehended as a faithful representation. As the architectural historian Anne Hultzsch has noted, at the time the built environment “was one of the key ingredients to situate stories, to make them real.”Footnote 26 Meticulously reproduced details of buildings, ornamentation, and spatial arrangements, often transferred directly from other printed sources, provided a way of anchoring the image in space and created reality effects through details. Over time, with the growing specialization in the studios of the illustrated press and increased capacity to render both architecture and people in greater detail in rapidly produced news images, these pictures grew ever more detailed. In their more extreme applications later during the 1840s, these images often created a kind of fish-eye effect by trying to encompass a wider field of view than usual in perspective drawings: in the interest of summarizing the size of the crowds assembled and the details of the settings, artists and engravers created images that could simultaneously give an overview of the people and document the spacious halls where they met (elaborate ceilings were often a dominant trait, as in fig. 1).

There were also other and perhaps less illusionistic mechanisms at work in images such as the one reproduced as figure 1—most importantly, what can be called a form of disembodied viewing. Used here is a very common practice in the illustrated magazines of representing an event from a detached and slightly elevated position. This positioning of the viewer has often been noted in earlier research.Footnote 27 Peter Sinnema, for example, talks about a “specific type of . . . illustration, the generic requirements of which include an elevated perspective and the ambition to encompass a large, panoramic scene” and describes this as an “ideological construction” that “consistently engages in the erasure of trauma” by obscuring social conflict.Footnote 28 According to Andrea Korda, this same viewpoint “helped cultivate a new standard of immediacy” by a “trick” that “denies the bodily presence of the author,” leading the reader-viewer “to believe that they are seeing the event for themselves.”Footnote 29 This use of an elevated viewpoint has thus been regarded as somewhat unnatural, not least since no real observer could have been located at such a point, or even as a way to dissimulate the true state of things since it produces a false sense of detachment and control. This may well be true, but what is interesting here is less the power relations inherent in this type of representation than the ubiquity of the formula and how it was used to summarize information about surroundings and people attending an event, for example.

In many ways this disembodied and detached way of viewing was an adaptation in wood-engraved news images of compositions traditionally used in both view-paintings and single-sheet prints depicting ceremonies and public gatherings.Footnote 30 It is safe to say that this representational mode in itself was nothing new at the time, and the ability of such images to deliver truths about newsworthy occurrences would not have been questioned by most reader-viewers. But this production of news images using standards and formulae from the tradition of views, printed or painted, is only part of how the illustrated magazines communicated public events. Frequently the settings were also filled with human actors in the foreground, and by focusing more directly on individual participants the images evolved from “views” into “scenes,” though the disembodied viewpoint and sense of detachment was often retained even as the images zoomed in on action and character. Convincing and telling scenes were primarily achieved using two pictorial devices, type and narrative.

Types in news reporting

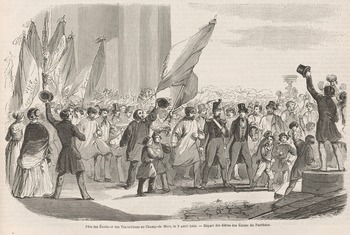

Typological aspects in the depiction of people—where the figure represented is intended to stand for a group or class—were of course present in a range of images in the middle of the nineteenth century, from caricature to genre painting, but one of the most important contexts was the representation of social or political collectives in news reporting where group affiliation was key. An example can be taken from the visual reporting of political activities in Paris during the revolutionary spring of 1848. According to the caption, the image reproduced here, taken from L'Illustration in 1848 (fig. 2), describes a procession of students and workers during a collective “fête.”

Figure 2. L'Illustration 11 (1848): 83.

In the center of the image is a stylized bearded worker in blouse and cap, a representative of the military in the costume of the national guard—a highly charged representative figure since the guard was seen as a people's army with elected officers—and a young bourgeois in a tailcoat and top hat (presumably a student). The three figures in the middle are looked up to by children running around and framed on both sides by enthusiastic male onlookers in fashionable frock coats and striped pants, as well as elegantly dressed women, an apparent sign in uncertain times of peace and order at events like these. To the left, a group of mostly proletarian characters (some carrying tools) serves as a backdrop to the three central figures, and their marching into the picture from left to right gives a strong sense of forward direction. By this arrangement of clearly legible types, and especially by the highlighting of the three central figures, L'Illustration gives a visual account of the event and its meaning with the help of a sort of pictorial shorthand. It conveys information about groups that took part as well as atmosphere and significance. In the end, of course, this particular image is one of national unity and progress, and it was obviously important for L'Illustration to show that the working classes as well as bourgeois groups were united in the spring of that year, not least since rumors were circulating about threats against the order imposed by the new republican government by unemployed workers.Footnote 31

If it is obvious that standardized features were regularly used to talk about group attendance at public events, the types could, however, be executed in many different ways. Figures could, for example, both be “composite images,” meant to summarize characteristic traits in a made-up figure, and naturalistic depictions of specific individuals that were deemed to be characteristic of a class.Footnote 32 Regardless, it is important to note that the illustrated weeklies were during this period heavily influenced by both artistic genres like caricature and scientific physiognomy.Footnote 33 The affinities between the use of types in news images and the wave of popular sketches of manners that were published during the 1830s and 1840s should also be stressed. Illustrated magazines during the 1840s, for example, were closely related to a well-known phenomenon like the “physiologies” and also to the larger collective sketch productions depicting manners that were produced in several countries during the decade, works that were in many cases illustrated by the same artists that worked for the illustrated weeklies.Footnote 34 Images from such publications were often published in the illustrated magazines, not least in L'Illustration, which even had a special heading for “mœurs et coutumes, scènes populaires, types divers.”Footnote 35 More important for the present argument, though, is that such representational conventions also contributed directly to news imagery, and to images of ceremonies and public events in particular. The appetite for generalization became important for the development of pictorial representation in general in early illustrated periodicals, and the border between the satirical or comic and typologically inclined images of current events was never strict.

As Martina Lauster has shown, the verbal and visual sketch can be seen as part of a new kind of social description that developed simultaneously in different urban centers of western Europe, in Paris and London but also in cities of the German-speaking world like Berlin and Vienna.Footnote 36 The visual-verbal sketches that were popular during this period did not aim for individual physiognomy but were part of an emerging culture of knowledge that investigated “the social,” not least by relating human features, dress, and manners to occupational and other surrounding contexts: the “countenance” in this case often did not “offer a key to passions and character, as in traditional physiognomic reading, but to an environment that produces such expressions.”Footnote 37 Related ambitions can be seen in the use of types to summarize public events; based on information about attendance and atmosphere, whether in the form of written or oral reports or direct observation, such standardized indicators could be used to sum up the presence and interaction of different collectives. As in figure 2, this meant that typological forms of representation could be used to formulate summary statements about the character of an event—its most important features or essential meaning—that were possible to decode by a general reader-viewer based on a knowledge of types.

Episodic narratives

Another important aspect of the images in question concerns narrative structure. Both traditional and more innovative means were used to depict action and to “condense many moments into summary ones” in 1840s illustrated newsmagazines.Footnote 38 It was not uncommon that images related a story that unfolded in time or compressed several occurrences into one pictorial representation, and in this respect they were directly related to established modes of narrative picture-making, not least the still highly valued genre of history painting.Footnote 39 As Ulrich Keller argues in his visual history of the Crimean War, the authority of history painting in the middle of the nineteenth century was still such that artists who worked in newspaper illustration “eagerly drew on high-art traditions, not only to fuse factual correctness with aesthetic pleasure and to legitimize their ‘parvenu’ media, but also . . . to be understood . . . in a milieu of unbroken rhetorical traditions.”Footnote 40 Narrative of this kind was, unsurprisingly, most common in imagery related to the traditional subject matter of academic painters, like the battle scenes discussed by Keller, but it was also frequently used for other occurrences of a dramatic nature, like accidents and violent crime.

Narrative conventions also played an important role when staged public events were depicted, but often in quite specific ways. It is sometimes possible to recognize the classic techniques of history painting, like a focus on the “significant moment,” namely, a moment of high drama that captures the essential meaning of an event as well as virtues and vices of the protagonists, even though such devices were often used in a less high-strung fashion in these mass-produced images than in grand-manner history painting. For example, crowd behavior could sometimes be described in this way when the focus was on emotional peaks or outbursts of either sympathy or violence that summarized the character of the event itself and its collective actors. But as two examples will demonstrate, it was perhaps more common that representations of public events were narrative in the sense that they contained several actions in one image in the form of microstories, actions that in reality would have occurred at different times. Such “episodic narratives,” as they have been called, were also common in mid-nineteenth-century battle painting, an artistic practice that not only related recent events in a way that was similar to news images but also had many personal connections to the illustrated press.Footnote 41

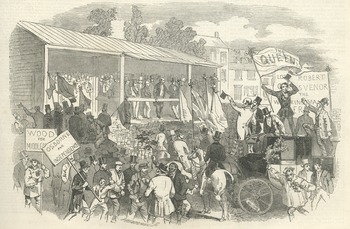

The first example of such “narrative accumulation” shows a political meeting in England, the hustings at Brentford outside London during the general election of 1847 (fig. 3). This wood engraving of a speaker and his audience relates the story of popular political participation in a country sharply divided in terms of class. It shows a lively meeting, and the figures indicate the different social groups that took part in the event, some more directly as electors and some only in secondary roles as part of the crowd. The viewpoint is slightly elevated, which permits a representation of the audience as large. At the same time, the speaker and his entourage on the platform and the onlookers in the foreground are arranged side by side forming a large oval that surrounds the schematic representation of the audience in the center, so as to permit a rather detailed presentation of participants in terms of both dress and pose. Both elite electors in their coats and with “tall” hats, and members of popular groups dressed in gowns and caps typical of working men, are clearly identifiable. In the foreground is even a character with a rough countenance and a dustman's hat, representing a popular figure (“Dusty Bob”) in the visual culture of the time.Footnote 42

Figure 3. Illustrated London News 11 (1847): 89.

In terms of action, several things are happening at the same time. The most apparent narrative concerns the candidate speaking and the response of his audience: members of the audience seem to be responding to what the speaker is saying by raising their hats in agreement, even though he is apparently still speaking. As Joshua Brown has noted, this type of time compression, where both the action of the speaker and the response of the audience are pictured at the same time, was typical in images of public meetings in the middle of the nineteenth century.Footnote 43 In the foreground there are also a number of micronarratives, with some figures entering the picture frame with political signs (presumably supporting other candidates) and another one running toward the crowd with a branch in his hand, eager to take part in the collective manifestation of support for Lord Robert Grosvenor. In this way, the image summarizes several separate occurrences and presents a picture of the many things that happened during the day according to the textual reports in the press, while it also thematizes the importance of popular participation at public events like these.

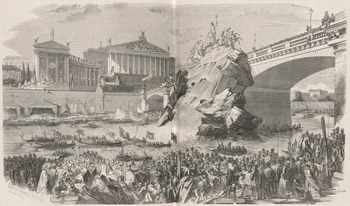

The second example is, in a way, a bit strange since it was published as being not true to the facts. It is a wood engraving of the festivities in Paris on May 4, 1851, to celebrate the third anniversary of the proclamation of the second French Republic (fig. 4). In an accompanying article, the editor of L'Illustration, Jean-Baptiste Alexandre Paulin, a moderate but steadfast republican, describes the image as a representation of how the festivities would have looked if the authorities had not failed to put together the promised show on the Seine, and if there had been any true popular enthusiasm for the celebration of the veining republic. Interestingly, the image was described as “very accurate in terms of the main view,” even though the picture had also “adapted [traduit] the program and thus added to reality.”Footnote 44 Through the ironic frankness of Paulin, we get a glimpse of practices that were probably widespread in news illustration at the time, that is, “adaptions of the program” as a way to convey the content of events rather than direct observation.

Figure 4. L'Illustration 17 (1851): 296–97.

This image is based on drawings by two artists, Henri Valentin, known for his genre scenes and French popular characters, and Édouard Antione Renard, who often drew buildings and architectural elements.Footnote 45 In this particular case, their contributions summarize different aspects of how public events were generally represented. This image contains detailed renderings of both the National Assembly (the Palais Bourbon) and the Concorde bridge as well as some of the temporary architecture and sculptures commissioned for the occasion. As in most images of this kind, the elevated viewpoint permits the representation of crowds gathered, both on the steps of the National Assembly and on the banks of the Seine. Since the image is large (it was printed from several bolted blocks over two pages in the magazine), it is possible for Henri Valentin to delineate the people gathered in the foreground in some detail. We see both men and women as well as both bourgeois and proletarian members of the public. In this section of the image, several distinct but related episodes occur. Most notably, as a clear counternarrative to the official description of the festivities—“the program”—in the foreground a comic episode can be seen where the platform collapses under the weight of a group of spectators. The use of episodic narrative to relate such a mishap clearly goes hand in hand with the description of the event as a failure in the accompanying text, and it can also be seen as a critique of those that came to watch this fake-republican ceremony. This interpretation is supported by the fact that a representative of the working classes, a man in a blouse to the right in the picture, is seen pointing gleefully at the unfortunate group.

The pictorial strategies discussed so far could thus all be used to piece together bits of information and so provide a summary event for the reader-viewer, what I would call a synoptic condensation. Even though eyewitnesses being present at the scenes were occasionally mentioned, there is not much to suggest that news illustration of this type sought to portray events as they would have been experienced by an actual observer. Instead, the visual representation focused on the essential rather than on what could be perceived as superfluous detail, and often the images were adaptations of information from many sources, drawn sketches and other prints, as well as written reports and published programs. As these examples indicate, the strategies discussed were used to relate, not how a public event might have appeared at a specific moment or from a specific point of view, but rather something more analytic. By using the possibilities inherent in the medium of wood engraving to create both all-encompassing overviews and narrative scenes, the magazines could both summarize events and say something about their essential meaning. Even though it is sometimes hard from today's perspective not to either dismiss these images as essentially untrue or to look at them like failed snapshots of occurrences, in a news culture that was still not much affected by the invention of photography, ways of working that condensed available information would probably have been expected of reportorial images.Footnote 46

Even though it cannot be described in any detail here, it is also clear that to appreciate how such news images functioned, it is necessary to consider the role they played in the illustrated magazines as periodicals. The periodicity of the magazines created specific medial affordances that contributed to how certain effects could be achieved and much of the cultural force of these publications can be attributed to their serial nature. It has often been noted that the images published by early illustrated newsmagazines were repetitive. But this was also their strength: the “illustrated periodical's unique power was that of visual and textual repetition,” as Gerry Beegan puts it.Footnote 47 And as Hartwig Gebhardt has argued, it is only by considering the incessant repetition of subject matter in early illustrated magazines that we become aware of the extent to which they also relied on and developed specific “Bildmustern” (image patterns), crucial to how the images were interpreted and experienced.Footnote 48

If the purpose is to understand how the images in these magazines could have been experienced, it is thus important to look not only at individual cases but also at how they functioned as part of longer series of similar representations. As indicated by the examples already discussed, the pictorial strategies used in representing public events functioned through the repeated use of certain means of expression that would eventually have become easily recognizable (if not always consciously) to readers familiar with the illustrated press. Magazines after a while established typological features that could easily be used to indicate popular or elite attendance at public events and, for example, certain conventional gestures that suggested speaking and audience response. Overviews with row upon row of heads created a crowd, and this crowd functioned as a sign representing interest in the proceedings. Furthermore, illustrated magazines not only repeated themselves, they also repeated representations in other media.Footnote 49 If we focus on images of staged public events, it is clear that they were often dependent on other modes of printmaking for the commemoration of important occasions in public life.

3. Allusion and Symbolism: Historicizing Events

Mid-nineteenth-century illustrated magazines created visualizations of contemporary events that relied on the information contained in newspapers and often took for granted that their readers were well familiar with the reporting in the daily press.Footnote 50 However, their dependence on this fast flow of information does not mean that they automatically followed other print media in what they reported or how. Rather, they often selected topics that were suited to pictorial storytelling and conformed to specific conceptions of what was important. For example, it was repeatedly stressed that occurrences of historical significance appeared in the columns of these magazines, events that were of interest to both present and future generations.

That the illustrated weeklies perceived their role as a visual chronicling of “history”—events that were seen as meaningful in relation to larger narratives linking past, present, and future—can be seen in their self-advertising texts. L'Illustration stressed its value as a pictorial record and wrote about how its images, “at the moment when the events are still in recent memory, do not have the same importance as they acquire when they are further away from their date of creation.”Footnote 51 The Illustrated London News called itself a “pictured register of the world's history,” and the Pictorial Times presented itself as “the graphic history of the world.”Footnote 52 The Illustrirte Zeitung explained that its unique value as a publication was closely tied to an ability to discern what was important among all that was reported in the daily press:

It is true that our magazine can never compete with the novelty of the daily papers, but it has on the other hand the advantage of being able to present nothing but important news in lucid summaries and well-arranged overviews, since, however short the span of a week may be, as time goes by the confusion of the days dissolves and the heart of the matter instead presents itself for our enjoyment.Footnote 53

As these statements indicate, the magazines were occupied with fixing an image for posterity as well as relating events for contemporary consumers. Or rather: they produced images for posterity aimed at contemporary consumers, which were thereby positioned as collectors or record keepers as well as participants in ongoing discussions.

That illustrated weekly magazines presented information in a way that suggested it should be kept as records, rather than be treated as something ephemeral, is not only manifested on a discursive level but can also be observed in how they worked as periodicals; the tendency to create history when reporting events was clearly expressed on a material level by the way the magazines were produced. Illustrated magazines such as these, primarily aimed at well-to-do audiences, were normally printed on rather expensive paper that was also durable; they were usually sold on a subscription basis and were meant to be bound into volumes, two per year. At the end of each year or volume, new title pages, frontispieces, and elaborate indexes to both pictorial and textual content were regularly published. There are also indications that earlier numbers were sometimes reprinted so that later subscribers could complete their collections.Footnote 54 Another example of how the editors created pictorial archives was the production of special issues and supplements to document certain occurrences. The collecting of pictorial documentation of especially important events during the period of study culminated in the compilation of supplements on the revolutions of 1848 and later the Crystal Palace Exhibition in 1851.

That illustrated weeklies sought to record that which had lasting significance and were in many ways produced as keepsakes, meant to be bound into volumes and presumably also reread, has of course been noted before since this is the way we encounter the periodicals in libraries today, but it has not really been analyzed in terms of how it was connected to the temporality of news.Footnote 55 The same goes for the images themselves and how events were represented within the picture frame. In news images of public events, the “historicizing” tendency is expressed on many levels. As already discussed, events were summarized and images therefore became historical in the sense of narrative condensations of actions that unfolded in time. It was also common that typological features were used to portray collective actors of historical importance in such images (“the citizens,” “the working classes,” “the people”). Furthermore, news images often contained a range of allusive and symbolic elements that helped portray events as historical, in the sense both of being connected to larger processes and of being important. Three further examples of public mass gatherings can illustrate how this historicizing tendency worked by the incorporation of allegorical elements, references to other well-known images, and the use of formats derived from traditional commemorative prints. As the examples will make clear, these practices were closely tied to the modes of truth-telling discussed above—the historicizing tendency was an integral part of the synoptic visual rhetoric used.

Commemoration and the use of allegory

When public events, particularly of a political or civic nature, were celebrated as successful, ornate images were often produced where allegorical elements emphasized their importance and related them to earlier events. Such elements were most often used as a framing device but could on occasion also be incorporated into the representation of the main subject. Regardless, the distinction between the naturalistic and the allegorical often became fluid.

One example of such practices was the English remake (fig. 5) of the French image discussed above (fig. 4), depicting the republican celebrations in Paris in May 1851. In the wood engraving of this event published in London, a rather standardized allegorical apparatus has been added to an image that otherwise contains much the same information about the celebrations as the French picture (though without the bitterness and the critique). In this version of the event, different aspects of the celebrations have been compressed into one image, not only chronologically but also spatially. Most importantly, the temporary statues of heroes from French history, specially commissioned for the occasion and in reality placed in different locations in the city, are here depicted together in a row to the left. Together with allegorical figures in the sky and to the right in the image (a version of Marianne, the personification of the republic), they both literally and symbolically frame the action. The framing is completed by a line of more ordinary figures in the foreground, which could perhaps have been seen as representations of actual people present at the scene, if it were not for the rather excessive use of typological features. When a “laborer” embraces a “soldier” in the lower right-hand corner, the figures acquire a symbolic role that makes them hard to distinguish from the purely allegorical. Taken together, this is an image that mixes naturalistic and allegorical elements in a way that creates a sort of dreamscape of contemporary history.

Figure 5. Illustrated London News 18 (1851): 462.

As Evonne Levy has suggested in an early modern context, allegory can in a situation like this be seen as an indication that “eyewitness images” were understood as “inadequate historie, as insufficiently interpreted.”Footnote 56 That is, allegorical additions to documentary images could serve the purpose of situating them in a larger narrative context and point to specific features of importance for how they should be apprehended. In the example discussed here, such additions demonstrated, in an almost exaggerated way, that the young republic was a historical feat to celebrate but also that the festivities themselves were well worth remembering. Allegorical figures with similar roles can in the illustrated magazines be found in representations of a range of other public events during these years, both celebrations of royal anniversaries and military victories and less political events, like agricultural fairs and scientific conferences. In these cases as well, the allegorical was often an addition that served to frame the central action in an otherwise naturalistic-looking depiction, even though it sometimes invaded the representation of the event itself. What these images generally had in common was the desire to commemorate, that is, to convey to posterity events that were seen as worth remembering while celebrating them as achievements in the here and now.

References and the creation of historical connections

Another way to fill documentary images of public events with historical significance was by linking them to how important occurrences had previously been pictured, preferably in high art contexts and more exclusive media like copper engraving. A category of images that well illustrates this point is the representation of political meetings, a common topic in the illustrated press during the 1840s that was closely related to contemporary debates about popular rule and sovereignty. Public demonstrations of this kind were closely connected to discussions about the legitimacy of government and who could speak for “the people” or represent “public opinion.”Footnote 57

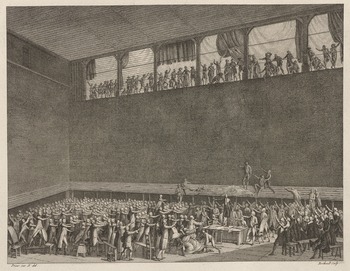

This discourse also found expression on a pictorial level, as exemplified in figure 6. Represented is the founding meeting in 1846 of the liberal party of Belgium in the Salle Gothique of the Town Hall in Brussels. As was often the case with pictures meant to commemorate events of this kind, this image was reproduced in several media. In this case it was published both as a single-sheet print (a lithograph) and as a wood engraving in the illustrated press. The representation focuses on the audience response to a speaker at the far end of the vast hall, and the gestures used to express adhesion to what is being said contain an unmistakable reference to an image that had already at the time become something of a visual icon, Jacques-Louis David's Le Serment du Jeu de Paume, or rather the many reproductions and remakes of the study for that unfinished painting that circulated in the first half of the nineteenth century. One version of that foundational event in European political history inspired by David's original sketches, which would have been widely available at the time, was the engraving in the influential collection Tableaux historiques de la Révolution française reproduced here (fig. 7).Footnote 58

Figure 6. L'Illustration 7 (1846): 276.

Figure 7. “Serment du Jeu de Paume, à Versailles le 20 juin 1789,” in Tableaux historiques de la Révolution française (Paris: Pierre Didot, 1791–1804).

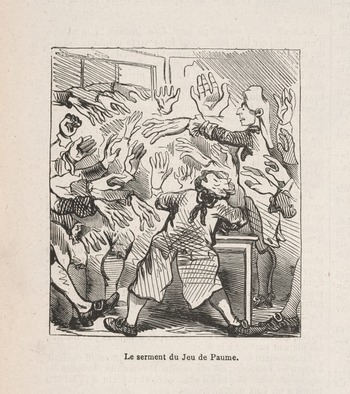

Here one can observe the raising of hands, a classicizing expression taken from David but reused in a documentary composition that focuses on the collective as a whole rather than the individual figures that would have been at the center of his more traditional history painting. A similar collective body is suggested in the image of the founding of the Liberal Party of Belgium, and by association it becomes possible to see those present at that meeting as representatives of the people in a more general sense. It is important to note that the reference, and the associations to questions of sovereignty that came with it, would hardly have been lost on reader-viewers at the time. As indicated in a caricature by the French artist Cham (Amédée de Noé), referring to a painting with a similar theme exhibited at the Salon in 1848, the gestures used in the image had already by the late 1840s become cliché to the point of invoking ridicule (fig. 8).

Figure 8. L'Illustration 11 (1848): 140.

This example is perhaps extreme since the image in L'Illustration is almost overambitiously trying to connect a later political meeting to one of the founding moments of modern popular politics.Footnote 59 But whether an extreme example or not, the general tendency to explicitly or implicitly invoke earlier representations of well-known moments of history was widespread in imagery of this kind. Images of political meetings, if we stick to that example, could reference a whole tradition of political iconography where gatherings of people were described as expressions of popular will or the rising up of the people against oppressive regimes, for example, in the many popular lithographs of revolutionary events in 1830 in countries such as France, Belgium, and Switzerland. By associations like these, quite commonplace events in themselves could be visually connected to fundamental debates about power and rule in modern society. By placing new actors into recognizable representations of earlier events, pictorial connections were established that suggested new occurrences were the continuation of longer developments, and often that the actors depicted were part of the same collective subject acting in history. On a more general level, images of public events could gain in both interest and legibility through pictorial connections of this kind, and it was one important way to make contemporary events a continuation of “History.”

Reusing conventional formats

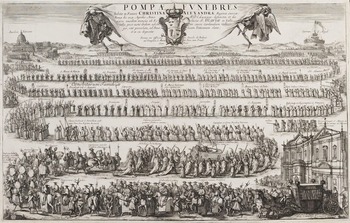

If one way that public events were made into history was by reference to iconic or well-known images, another was by the use of conventional formats that also tied the present to the past. One significant example is how processions were often represented in illustrated magazines. As Anne Hultzsch has noted in an analysis of parades, the Illustrated London News often let a pageant “walk across its pages” in “an s-shaped movement” during the 1840s, something that she interprets as a way to capture and represent modern urban “flux.”Footnote 60 However, a serpentine presentation of figures marching was also an old pictorial convention, and its use in a mid-nineteenth-century context carried specific symbolic meanings tied to this fact.

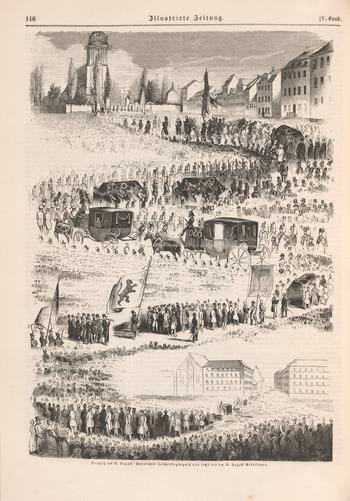

How the formula could function in the illustrated press can be seen from a wood engraving in the Illustrirte Zeitung of a funeral procession (fig. 9) held in the wake of an event in August 1845 known as the “Leipziger Gemetzel.” During a visit by the brother of the king of Saxony, a staunch conservative, a crowd assembled in the city square to protest, and when it became unruly, royal troops fired on the people, killing eight. As part of large protests against the violence, organized by the radical politician Robert Blum among others, a stately funeral was arranged for those killed. Great indignation about the incident is noticeable also in the Illustrirte Zeitung, a magazine based in the city, and most of the issue from which the image reproduced here is taken is dedicated to the events some ten days before. In this image, the typical s-shaped composition presents the marchers both integrated in and abstracted from the context of the city and parading into a distance. The representation is structured to be viewed as a condensation that summarizes the parade walking by, not from any real-world viewpoint but with the help of a conventional line that meanders across the page and an imaginary space between two well-known locations. The procession emerges from a city street and the dense crowds represented in the bottom of the image, and then dissolves in the multitude again at the end of the march, toward the Johanniskirche at the top left. With reference to the pictorial strategies discussed earlier, it can be noted that this composition gives room for the depiction of types in that participants in the procession are partially seen lined up from the side (one notices both officers from the Communal guards and male citizens from different social classes), while the general emphasis is on the multitude watching the spectacle.

Figure 9. Illustrirte Zeitung 5 (1845): 116.

This way of representing a parade reaches back to early modern ways of picturing the processions of elite groups in European society. For example, the serpentine composition was well represented in so-called festival books, popular among courts and rulers in early modern Europe, and in engravings of such important ceremonies as royal marriages, city entries, and funerals.Footnote 61 One elaborate but otherwise typical example of this common format is the funeral procession in Rome at the end of the seventeenth century of Christina, former queen of Sweden, from the church S. Maria Vallicella to St Peter's Basilica (fig. 10). In this engraving, the detailed recording of participation in the procession served political purposes related to the conversion of Christina to Catholicism, and it can be assumed that this occasioned both the extravagant funeral itself and the production of the engraving. Equally, political interests can often be detected behind the use of this kind of composition in the mass-produced lithographs and wood engravings of the nineteenth century. Here the orders and corporations (specified in the text in fig. 10) would be replaced by social types, but the representative function would essentially be the same.

Figure 10. Funeral procession of Christina, former queen of Sweden, copper engraving by Robert van Audenarde, published by Giovanni Giacomo de Rossi in Rome (1689).

Such long-standing traditions of representation obviously suited synoptic pictorial strategies focused on summarizing events, but it is also important to note that the use of these specific conventions—for example, in a politically charged atmosphere where civic-minded burghers protested the monarchical abuse of power—could also give occurrences a specific standing: this was how important people and ceremonies had always been portrayed in the prestigious print productions of the elite, and now it was used for a mass-produced news image of the funeral of ordinary people killed in the streets. In other words, it can be assumed that the symbolism of the event was enhanced by the use of established modes of representation associated with rulers and elites, and the use of such a formula can be seen as another example of how the illustrated magazines historicized events. By describing the procession in this way, the Illustrirte Zeitung effectively helped elevate what could have been ephemeral into an event of lasting importance, while telling their local readers that what they had just experienced was of historical significance.

4. Synoptic Images and the Time of News

The examples discussed have shown how illustrated newsmagazines during the 1840s summarized public events with the help of what can be called a synoptic visual rhetoric, and that an ambition to create records for posterity, to produce something lasting rather than ephemeral, can be observed on several levels: in the production and organization of the magazines as printed products, in self-advertising texts, and in the images themselves. It is clear that this way of working created visualizations of events that were, in many ways, orderly and informative but at the same time detached from the experiences of actual participants. They also permitted the mostly elite readership of these magazines to consume many events as spectacular and entertaining, rather than emotionally disturbing or threatening.Footnote 62 This is important, but even more interesting is how the visual reporting of events in synoptic overviews contributed to a specific temporality of news.

If by modern news time we mean a fast rhythm where the “idea of ‘news’ and the significant ‘event’ depends upon an evenly paced diachronic linear model of time that moves ever onwards, discarding each day as it passes,” it is clear, on one hand, that illustrated newsmagazines were closely connected to such a temporality.Footnote 63 In summarizing the news in pictures at weekly intervals—in itself made possible by the rationalization of artistic work and the development of the printing process as well as new organizational tools—these publications surely both speeded up and regularized the visual representation of topical events for a mass market. On the other hand, and as the examples here have shown, they also did more than contribute to a faster and evenly paced time of the news, both in how they condensed and in how they historicized events.

In summarizing information from different sources, these publications also arrested and compressed time. The now produced by the synoptic images of public gatherings discussed was not the “now” of an embodied viewer—an impression or a glimpse—it was a now made up of several moments and points of view. Contemporary reader-viewers would probably have taken this for granted; they would not have looked “through” the images toward an unmediated impression of the real from a specific viewpoint at a specific time, but rather have seen them as summary statements about what was important to know, and judged their informational and aesthetic value according to how well they captured the event in general. A mid-nineteenth-century consumer of news would thus probably have seen “whole events” rather than have experienced time as made up of instants or moments. This experience would then be reinforced by the tendency to present the occurrences depicted as historic. In producing images that recorded, archived, and commemorated, the magazines insisted that the now being pictured was not only of relevance to audiences in the future but also a continuation of larger historical processes: it was instant visual history, in many ways the opposite of the ephemeral that is often associated with news.Footnote 64

Against this background, it is reasonable to suggest that one important contribution of the early illustrated press to modern news time, at least if we take the examples discussed here to be representative of more general tendencies toward synopticism, was how it helped establish the very events on which a sense of fast, forward movement could be construed. In a sense, synoptic images of the kind discussed functioned in opposition to the fast flow of information: it was by slowing down, by selecting and by summarizing, that they contributed to an overall acceleration of time. For there to be direction, there had to be significant events, and when such events were produced with pictorial means in the weekly illustrated press, these publications powerfully contributed to a nascent culture of “eventfulness.”Footnote 65