Introduction

Data-driven methods for materials development have become increasingly prevalent over the past decade.[Reference Raccuglia, Elbert, Adler, Falk, Wenny, Mollo, Zeller, Friedler, Schrier and Norquist1–Reference Agrawal and Choudhary5] One widespread machine learning approach for materials development is screening.[Reference Meredig, Agrawal, Kirklin, Saal, Doak, Thompson, Zhang, Choudhary and Wolverton2,Reference Curtarolo, Hart, Nardelli, Mingo, Sanvito and Levy6–Reference Kim, Huang, Jegelka and Olivetti8] In materials screening, a machine learning model is trained to predict materials properties given the chemical formula and processing information and then is applied to a set of candidate materials to predict their properties. The materials predicted to have the best performance are then selected for experimental testing. Meredig et al.[Reference Meredig, Agrawal, Kirklin, Saal, Doak, Thompson, Zhang, Choudhary and Wolverton2] applied this screening approach to sift through millions of potential ternary compounds to surface thermodynamically stable combinations. Ward et al. [Reference Ward, Agrawal, Choudhary and Wolverton9] showed how a similar approach could be used to find bulk metallic glasses.

A related data-driven approach is sequential learning, also known as active learning.[Reference Butler, Davies, Cartwright, Isayev and Walsh10,Reference Granda, Donina, Dragone, Long and Cronin11] This workflow involves pairing the machine learning model with a sampling or optimization routine to select new experiments to perform, then iteratively retraining the model using the new data so that it can provide successively more informed suggestions. Ling et al.[Reference Ling, Hutchinson, Antono, Paradiso and Meredig12,Reference Ling, Antono, Bajaj, Paradiso, Hutchinson, Meredig and Gibbons13] illustrated how this approach could be applied to a variety of application cases, including the development of high-temperature superconductors, resilient superalloys, and novel thermoelectric materials. Sequential learning relies on having a machine learning approach that includes uncertainty estimates and is particularly valuable in application cases with sparse or small data sets that might result in initial models with high uncertainty.

Both materials screening and sequential learning provide data-driven approaches to selecting which experiments to run next. This paper discusses a related use case for machine learning in materials development: guiding project direction via design space visualization. Design spaces are the set of possible materials under consideration for an application given a set of constraints. Kim et al.[Reference Kim, Kim, Antono, Meredig and Ling14,Reference Kim, Antono, Kim, Meredig and Ling15] recently showed that the quality of a design space is correlated with the likelihood of a sequential learning project to find high-performing materials and presented a quantitative approach to predictively evaluate design space quality. This paper builds on that framework, adapting it for the use case of guiding project direction via visualizations of the design space performance.

Conventional methods for making complex decisions with multiple objectives and constraints, including multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA), which has been widely used in both health care[Reference Diaby, Campbell and Goeree16] and natural resource management,[Reference Herath and Prato17] often rely on expert opinions to evaluate both the importance of various criteria and the likelihood that a given approach will meet them. The approaches presented in this study represent a data-driven alternative for determining the likelihood that a set of objective targets can be met given a set of constraints.

This communication presents a design space visualization approach and demonstrates the visualization's application to two case studies: assessing the impact of imposing a biodegradability constraint on solvent performance and evaluating the effect of constrained materials sourcing on lithium-ion battery cathode performance.

Methodology

Our approach to design space visualization is focused on assessing the likelihood that an enumerated set of candidate materials (the design space) contains materials whose properties extend into any given point in a two-dimensional material property space (called the “output space” below). Importantly, these visualizations illustrate material property predictions and their estimated uncertainties, which are calculated using predictive machine learning models with well-calibrated uncertainty estimates.[Reference Ling, Hutchinson, Antono, Paradiso and Meredig12] Within this scope, there are a variety of ways of visualizing the performance of a given design space. In this work, the focus is on two main strategies described below.

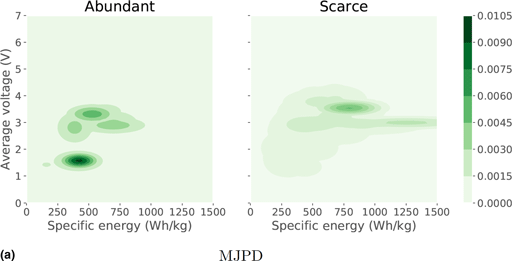

The first visualization strategy is the maximum joint probability density (MJPD), which provides insight into the probability of reaching a given region in output space given the best candidate in the design space. The second strategy, summed probability density (SPD), gives the predicted density of candidates in the output space. Both strategies utilize contour plots with the output space shown on the x–y axes, with the z-axis (represented using a color map) showing either the MJPD or SPD at that point in the material property output space.

These strategies incorporate a similar treatment of candidates and their predicted properties. Each output is described as a normally distributed random variable ![]() $T_k \sim {\cal N}\lpar \mu _k\comma\; \sigma ^2_k\rpar$ with probability density

$T_k \sim {\cal N}\lpar \mu _k\comma\; \sigma ^2_k\rpar$ with probability density ![]() $\varphi _k$. Since multiple objectives are of concern, a candidate with d>1 objectives may be defined as a set of random variables with a joint distribution ρ:

$\varphi _k$. Since multiple objectives are of concern, a candidate with d>1 objectives may be defined as a set of random variables with a joint distribution ρ: ![]() $C=\lcub T_k\rcub _{k=1}^d \sim \rho$. The first main assumption in these approaches is that the objectives are independent of one another, such that the joint probability density can be calculated from:

$C=\lcub T_k\rcub _{k=1}^d \sim \rho$. The first main assumption in these approaches is that the objectives are independent of one another, such that the joint probability density can be calculated from:

This can be a poor assumption in many cases where outputs are co-variant. Future work will assess the impact of co-variance in the outputs, as well as mitigation approaches. Despite this simplification, the resulting visualization is nevertheless useful for understanding which regions of output space are achievable with a given design space.

Additionally, a design space of n candidates is treated as a set candidates, each being a set of random variables, each with its own distribution described by the objective's mean and uncertainty, ![]() $D=\lcub C_i\sim \rho _i\rcub _{i=1}^n$.

$D=\lcub C_i\sim \rho _i\rcub _{i=1}^n$.

The MJPD takes the maximum value of the joint probability density for each gridded point in output space, ![]() $t^0$, over all n candidates in the design space, D:

$t^0$, over all n candidates in the design space, D:

Contour plots of the MJPD thus show the value of the joint probability density for the candidate most likely to achieve the property values at a given point in output space.

The second metric presented in this paper is the SPD, which sums the joint probability density over all n candidates at a given point in output space:

The resulting contour plot thus provides an indication of the density of design space predictions in the output space, factoring in the uncertainty of these predictions.

On an intuitive level, the MJPD plot indicates whether the current data and model suggest that a region of performance space is attainable by any single candidate in the design space. Conversely, the SPD plots indicate how easy it is to find a candidate in that region of performance space.

In this work, the machine learning algorithm of choice was a random forest, and the uncertainty estimates were calculated using jackknife-based methods detailed in Ling et al.[Reference Ling, Hutchinson, Antono, Paradiso and Meredig12]

Results

These design space visualization approaches are demonstrated in two case studies: one in biodegradability of organic solvents and another in sustainable sourcing for lithium battery applications. These two case studies were chosen because of the availability of public data. While these two case studies are both related to environmental sustainability, these approaches are broadly applicable to materials and chemicals development projects. For simplicity, these case studies both focus on application cases with exactly two output properties of interest. However, these methods can also be applied to applications with more output properties by creating multiple plots showing the two metrics (MJPD and SPD) over pairwise combinations of the output properties.

In each case study, the relevant data sets will be introduced, and the accuracy of the associated models presented. Then, the MJPD and SPD plots will be used to visualize trade-offs associated with environmental sustainability.

Biodegradability case study

Two different data sets were used in this case study. The first, from Reichardt et al.,[Reference Reichardt and Welton18] consists of 64 organic solvents along with their SMILES strings and common properties of interest such as their boiling point and relative polarity. A second data set, from Mansouri et al.,[Reference Mansouri, Ringsted, Ballabio, Todeschini and Consonni19] contains 1725 different simple organic molecules, with SMILES strings, features based on their molecular structure, and a classification of “readily biodegradable” or “non-readily biodegradable.”

Three random forest machine learning models were trained using the Citrination materials informatics platform.[Reference O'Mara, Meredig and Michel20] Two regression models were trained on the Reichardt data set, one for boiling point and another for relative polarity, using the SMILES string as the input for both. The Citrination system automatically featurized the SMILES string using a subset of the CDK feature library.[Reference Steinbeck, Hoppe, Kuhn, Floris, Guha and Willighagen21] A third model was trained on the Mansouri data set to classify the biodegradability of the molecule given the SMILES string and associated molecular features.

Figure 1 shows the predicted versus actual plots and receiver operator characteristic (ROC) plot for the regression and classification models, respectively. These plots were generated via threefold cross-validation to assess the predictive accuracy of the machine learning models for these properties. As these plots show, the regression models for boiling point and relative polarity have some predictive power but relatively high uncertainty (root-mean-squared error normalized by the standard deviation of 0.6 and 0.8, respectively). In contrast, the classification model for ready biodegradability has extremely high accuracy (with an area under ROC of 0.924).

Figure 1. Visualizations of machine learning model accuracy for the biodegradability case study. Predicted versus actual plots for (a) boiling point and (b) relative polarity, and receiver operator characteristic for predicting non-ready biodegradability (c).

Let us now examine how the design space visualization approach could be applied in this case. In this hypothetical, let us assume that researchers are trying to develop a new organic solvent with high relative polarity and high boiling point. Our design space of potential solvents includes the molecules from the Mansouri data set, and we want to determine to what extent imposing a constraint that the molecule be readily biodegradable will affect the achievable performance for those two properties of interest.

In this use case, we require the two machine learning models for boiling point and relative polarity but not the machine learning model for ready biodegradability. We use these two models to make predictions across the Mansouri data set for the properties of interest, then compare the MJPD and SPD plots for the readily biodegradable subset of the design space and the non-readily biodegradable subset of the design space, as shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2. Design space visualization plots for the readily biodegradable and non-readily biodegradable subsets of the design space. (a) is colored by the MJPD metric and (b) is colored by the SPD metric.

The plots in Fig. 2 suggest that there is no strong performance trade-off between readily biodegradable and non-readily biodegradable design spaces. The MJPD plot indicates that the predicted achievable performance is quite similar in the two design spaces. The SPD plot shows that the non-readily biodegradable design space has higher prediction density at higher boiling points, but the readily biodegradable design space has higher prediction density at higher relative polarities. In this case study, overall, the readily biodegradable design space seems at least as promising as the non-readily biodegradable design space for maximizing these two properties of interest.

It should of course be noted that there is no guarantee that the machine learning model is accurate over these design spaces. Since the design spaces were sourced from a different data set than the training data, the model is quite likely extrapolating for some of the design candidates. It is therefore critical to employ machine learning models with well-calibrated uncertainty estimates to capture this extra source of uncertainty due to extrapolation.[Reference Kauwe, Graser, Murdock and Sparks22] One significant benefit of the design space visualization strategies introduced in this paper—as opposed to a simple scatter plot or kernel density estimate—is the incorporation of uncertainty estimates into the visualization.

Sustainable sourcing case study

Three data sets were used in this case study. The first data set, which will henceforth be referred to as the “battery data set,” was based on the Materials Project[Reference Jain, Ong, Hautier, Chen, Richards, Dacek, Cholia, Gunter, Skinner, Ceder and Persson23] battery data set, subsampled to 513 common transition-metal-containing oxides. The stoichiometric range over the charged/discharged states was averaged to yield a single chemical formula per cathode material, and properties of interest include the specific energy and the average charge/discharge voltage (versus ![]() ${\rm Li}/{\rm Li}^+$) of the corresponding cathode material. The second data set, herein called the “sustainable sourcing data set”, was from Gaultois et al.[Reference Gaultois, Sparks, Borg, Seshadri, Bonificio and Clarke24] Its usage for battery cathode materials was motivated by the work of Ghadbeigi et al.[Reference Ghadbeigi, Harada, Lettiere and Sparks25] This data set includes the crustal abundance (in ppm) of each element. The third data set, which we will call the “candidate cathode data set,” consists of Li-containing compounds from the Open Quantum Materials Database[Reference Kirklin, Saal, Meredig, Thompson, Doak, Aykol, Rühl and Wolverton26,Reference Saal, Kirklin, Aykol, Meredig and Wolverton27] and the Crystallography Open Database,[Reference Gražulis, Daškevič, Merkys, Chateigner, Lutterotti, Quiros, Serebryanaya, Moeck, Downs and Le Bail28,Reference Gražulis, Chateigner, Downs, Yokochi, Quirós, Lutterotti, Manakova, Butkus, Moeck and Le Bail29] compiled on the Citrination platform. After removing materials already present in the battery data set, the candidate cathode data set contains 2851 compounds.

${\rm Li}/{\rm Li}^+$) of the corresponding cathode material. The second data set, herein called the “sustainable sourcing data set”, was from Gaultois et al.[Reference Gaultois, Sparks, Borg, Seshadri, Bonificio and Clarke24] Its usage for battery cathode materials was motivated by the work of Ghadbeigi et al.[Reference Ghadbeigi, Harada, Lettiere and Sparks25] This data set includes the crustal abundance (in ppm) of each element. The third data set, which we will call the “candidate cathode data set,” consists of Li-containing compounds from the Open Quantum Materials Database[Reference Kirklin, Saal, Meredig, Thompson, Doak, Aykol, Rühl and Wolverton26,Reference Saal, Kirklin, Aykol, Meredig and Wolverton27] and the Crystallography Open Database,[Reference Gražulis, Daškevič, Merkys, Chateigner, Lutterotti, Quiros, Serebryanaya, Moeck, Downs and Le Bail28,Reference Gražulis, Chateigner, Downs, Yokochi, Quirós, Lutterotti, Manakova, Butkus, Moeck and Le Bail29] compiled on the Citrination platform. After removing materials already present in the battery data set, the candidate cathode data set contains 2851 compounds.

Two random forest machine learning models were trained on the battery data set to predict the specific energy and average charge/discharge voltage. The input to the model was the charge/discharge-averaged material chemical formula, featurized using a combination of MAGPIE library[Reference Ward, Agrawal, Choudhary and Wolverton9] features and Citrine in-house element-based features available on the open Citrination platform.

Figure 3 shows the predicted versus actual plots for these two models. As this plot shows, relatively accurate models were trained for both properties of interest. The normalized root-mean-squared errors for the specific energy and average voltage were 0.6 and 0.5, respectively.

Figure 3. Visualizations of machine learning model accuracy for the battery case study. Predicted versus actual plots for (a) specific energy and (b) average voltage.

In applying design space visualization to this case study, let us assume that battery designers are trying to maximize specific energy and tune the average voltage to a specific value. The question that we would like to employ design space visualization to answer is what the performance trade-off in these two properties of interest is for materials that are scarce versus abundant. We compute the material scarcity as a weighted average of the elemental scarcity (the inverse of the elemental crustal abundance) over the material composition.[Reference Ghadbeigi, Harada, Lettiere and Sparks25] We split the materials listed in the candidate cathode data set into scarce and abundant design spaces based on material scarcity relative to a threshold of 10 ppb−1. This threshold yields 1595 and 1256 materials classified as abundant and scarce, respectively.Footnote 1

We apply the MJPD and SPD design space visualizations to these two design spaces, as shown in Fig. 4. The MJPD plots show that the scarce design space provides a much wider range of attainable performance. It suggests that the chance of finding a single cathode material with high specific energy is considerably higher with scarce cathode materials than with abundant cathode materials. However, the model tends to be most confident in its predictions of abundant materials having low average voltage and low specific energy. This is possibly because there are more abundant (314) than scarce (199) materials in the training set, many of which have properties in that range. The SPD plot shows that the predicted properties of scarce cathode materials are highly centered around 550 Wh/kg and 3V versus ![]() ${\rm Li}/{\rm Li}^+$. The predicted average voltage of abundant cathode materials spans a wider range.Footnote 2 Together, these visualizations suggest that scarce materials present the possibility of higher specific energy but more a constrained average voltage range. These plots therefore point to a trade off between using abundantly available materials and achieving maximal specific energy.

${\rm Li}/{\rm Li}^+$. The predicted average voltage of abundant cathode materials spans a wider range.Footnote 2 Together, these visualizations suggest that scarce materials present the possibility of higher specific energy but more a constrained average voltage range. These plots therefore point to a trade off between using abundantly available materials and achieving maximal specific energy.

Figure 4. Design space visualization plots for the abundant and scarce design spaces. (a) is colored by the MJPD metric and (b) is colored by the SPD metric.

Conclusion

In the course of a materials development project, there are many decisions that the researcher must make with respect to the design space of potential materials to consider. These decisions could pertain to what elements to include, whether to invest in a new piece of equipment to broaden the potential processing envelope, or whether to impose an additional constraint. In this paper, a design space visualization approach was presented that enables researchers to use a data-driven approach to assessing the impact of such decisions. This visualization approach is applicable to development projects where there are two or more properties of interest. In cases where there are more than two properties of interest, the MJPD and SPD plots can be generated for pairwise combinations of the target properties to visualize trade-offs. Furthermore, it is also possible to use this approach for cases with more than two possible design spaces. For example, for applications where toxicity, cost, and reliable sourcing are all potential constraints, multiple design spaces could be created with various combinations of constraints and their predicted performances could be compared using these visualizations.

The visualization approach was demonstrated on two case studies with relevance to environmental sustainability: one in biodegradability for organic solvents, and the other in sustainable sourcing for battery cathodes. Through these case studies, it was shown how the design space visualization approach could be used to assess the trade-offs inherent in design decisions. These particular case studies were chosen because of the mounting pressure on the materials and chemical industries to produce more environmentally sustainable materials. We therefore wanted to demonstrate how data-driven approaches can be used to help guide investments in environmental sustainability.

The application of machine learning methodologies to materials development has been widely applied to accelerating new materials development via active learning or screening approaches. The methods in this paper show a different use case for machine learning in materials development: aiding researchers assess the impact and trade-off of design decisions. More broadly, this work shows that machine learning is not confined to just suggesting which experiments to run next but rather can be used to aid at every decision point in the research process. At each of these decision points, the researcher can bring the available data to bear in order to make an informed, data-driven decision.