How do foreign investors use authoritarian institutions to protect their interests? Multinational corporations (MNCs) face high risk when investing in authoritarian regimes. One of the main challenges is that authoritarian courts are susceptible to external interference and thus cannot credibly commit to protecting foreign investors’ interests. Therefore, past studies have tended to dismiss the value of host-country courts as a feasible or reliable venue for foreign actors to settle their disputes and protect business interests in countries lacking the rule of law. For example, Ginsburg claims that “foreign investors are extremely loath to rely on local courts to resolve business disputes.”Footnote 1

Most research on foreign investment dispute resolution has focused on supranational legal regimes beyond host countries, such as investor–state dispute settlement (ISDS) mechanisms.Footnote 2 Nonetheless, as our new data set shows, multinational enterprises frequently use domestic legal institutions in the host country for a variety of issues. Thus far, we have known relatively little about the determinants of MNCs’ lawsuit success in host-state judiciaries, particularly in authoritarian regimes where judicial independence is not well established.

This study explores this under-explored question of domestic institutional protection of foreign investor rights: under what conditions do host-country judiciaries protect the interests of foreign firms? Foreign firms face a commitment problem in authoritarian host countries: neither state officials nor private entities can be held accountable for breaching contracts with foreign firms when the judicial system does not impartially enforce agreements. We argue that a key challenge for MNCs engaging in local litigation is to find ways to commit the host courts to protecting foreign enterprises’ interests. We investigate the effectiveness of two mechanisms through which foreign firms use authoritarian judiciaries to pursue their claims. More specifically, we theoretically and empirically distinguish between two types of government–business ties that MNCs can adopt, and compare how these mechanisms may address the commitment problem in authoritarian judicial systems. First, the MNC can build ad hoc political connections to engage in exchanges of favors with courts where state actors offer a “helping hand” in greasing the legal wheels. Second, the MNC may incorporate the state as a stakeholder of a joint enterprise such that dependent courts are inclined to look out for the interests of the collective partnership.

We argue that ad hoc political ties, characterized by personnel-based connections that conventional research has focused on, provide only superficial commitment by the state to protecting MNCs’ business interests. Foreign investors cannot leverage ordinary political exchanges of favors to secure substantial monetary remedies from dependent courts. In comparison, forging a joint venture (JV) with a state-owned enterprise (SOE) leads the state to structurally internalize the foreign investor's interests. The host state, as a stakeholder in the business partnership, has strong incentives to create systematic, institutionalized privileges—such as adjudicative favoritism by authoritarian courts—to benefit the collective enterprise. Thus a political partnership between the MNC and the state can more effectively commit the host authoritarian state to advancing the MNC's interests through judicial means.

Our arguments highlight the value of business partnerships between MNCs and state-affiliated actors in aligning foreign investors’ interests with regime interests, which generates rent-seeking opportunities under an authoritarian judiciary. A corporatized form of political relationship between foreign investors and host-country regime insiders can create more meaningful and substantial adjudicative security for foreign firms. Such partnerships can also address the commitment problem for foreign firms more effectively than superficial political exchanges.

To test our theory, we construct a novel data set on the litigation activities of MNCs in China since 2002, immediately after China joined the World Trade Organization. The data show that foreign investors actively litigate in Chinese domestic courts for various types of disputes with both public and private actors. Moreover, the empirical results consistently support our theory. First, in general, lawsuits by MNCs are more likely to result in shallow forms of success rather than in substantial monetary compensation. Second, conventional types of political connections are a relatively weak determinant of meaningful litigation success for MNCs. Third, foreign firms in JV partnerships with SOEs are more likely to receive substantial monetary reparations. All told, we demonstrate that foreign actors can rely on authoritarian judiciaries to address the commitment problem posed by a relatively unconstrained host government. However, the successful use of host courts by foreign firms to defend their interests depends on co-opting state actors as business partners.

To our knowledge, this study is the first to systematically investigate MNCs’ litigation outcomes in an authoritarian regime. It makes three key contributions. First, this project advances the political economy literature by showing how multinational firms’ political capital can address the commitment problem in cross-border rights protection through the use of host-country institutions. We show that “bad” institutions can in fact be valuable to foreign investors, especially when MNCs receive judicial favoritism from dependent courts as a result of rent-seeking arrangements with regime insiders. When the authoritarian state is incorporated as a stakeholder of the foreign enterprise, the two actors’ interests become more aligned; the partnership puts them “under one roof.”Footnote 3

Second, this work enriches research on institutions and development in authoritarian regimes. In particular, by empirically examining China's regulation of foreign investment in the judicial arena, our study contributes to theory building at the intersection of authoritarian legal systems, the international business environment, and political favoritism in economic development.Footnote 4 Given global firms’ heterogeneous preferences for investment protection,Footnote 5 this research helps us better understand the large variation in private investment in developing countries with highly corrupt judiciaries and weak property rights regimes.Footnote 6

Third, this study furthers our understanding of MNCs’ (dis)advantages in host countries by uncovering the conditions under which MNCs score lawsuit victories against host-country actors. By focusing on variation in MNCs’ corporate structure, this study rethinks the theoretical value of classifying host states as autocracies versus democracies, or countries with the rule of law versus those without, in evaluating political risk. While such macro-level divisions are important, we need more research at the litigant level. We suggest that strong political connections, market power, and the ability to offer bribes may all help MNCs wield influence over judges and obtain adjudicatory advantages. There is no shortage of anecdotal evidence suggesting that foreign firms with significant political and economic leverages win lawsuits against host-country governments when the courts are corrupt and unreliable.Footnote 7 Brutger and Morse even point out that international judicial bodies, such as the World Trade Organization, may also bend their rulings to accommodate the political clout of powerful member-states.Footnote 8 Likewise, our theory implies that the flip side of judicial dependency in authoritarian regimes is that susceptible judges may rule in favor of foreign firms when those firms have certain extrajudicial capabilities. Thus, our theory enriches the emerging scholarship on firm-level heterogeneity across multinational enterprises.Footnote 9

Finally, we acknowledge that the domestic legal channel is not a substitute for supranational legal mechanisms and that our study does not directly address MNCs’ “forum-shopping” behavior. Nonetheless, this research highlights the value of authoritarian judiciaries for foreign-related dispute settlement. We suggest that past studies have overlooked the possibility and too readily dismissed the merits of foreign firms’ pursuing dispute resolution in host-country courts. We show that MNCs may still win substantial legal victories in challenging institutional environments by deploying their political assets and exploiting institutional weaknesses. Analyzing the local forum of MNC dispute settlement provides important insight into the attractiveness of supranational institutions when those third-party venues do act as substitutes for or supplements to domestic institutions in certain cases.Footnote 10

The Commitment Problem, Judicial Institutions, and Investor Rights Protection

Conventional research on the relationship between regime type and foreign direct investment (FDI) flows highlights the role of independent judicial institutions in alleviating the commitment problem for foreign investors.Footnote 11 By tying the hands of government officials, independent legal institutions reduce the risk of state expropriation, contract repudiation, and bureaucratic malfeasance.Footnote 12 Put differently, when the host country lacks an independent judiciary, it is difficult to legally commit the regime to upholding the rights and interests of foreign investors. Chen, Pevehouse, and Powers find that, compared with democracies, the public believes that nondemocracies are less likely to treat foreign firms fairly in their domestic legal systems.Footnote 13 In this regard, most scholars have focused on the merits of supranational legal venues outside host countries (ISDS mechanisms, for example) in alleviating the commitment problems posed by host states to MNCs.Footnote 14

However, we still know relatively little about the conditions under which the domestic courts in authoritarian regimes can provide credible protection for MNCs. The question has been mostly overlooked because scholars often assume that authoritarian courts’ lack of independence would lead to adjudicative partiality and thus unreliable legal protection for MNCs. Nonetheless, we suggest that MNCs’ payoffs from resorting to authoritarian legal institutions cannot always be inferred from the inherent risk associated with such institutions. The institutional treatment of MNCs is shaped by the degree of interest alignment between foreign investors and the regime. Discriminatory state actions can be beneficial to MNCs under certain circumstances, depending on their relationship with the host state. For example, Wellhausen shows that, when government expropriations raise revenues for the state, bondholders may benefit because more money in government coffers suggests improvement and less risk in debt serviceability. Bondholders may even reward the government, although the revenues increase at the expense of foreign direct investors.Footnote 15 Thus, under certain circumstances the interests of foreign investors can be aligned with the state even in an adverse institutional environment.

In similar ways, the deficiencies of authoritarian courts do not entail that MNCs cannot secure meaningful protection of their interests. Scholarly understanding of the factors that incentivize authoritarian courts to safeguard MNCs’ interests is still limited. We suggest that it is important to examine MNCs’ sui generis performance in authoritarian courts as the first line of defense against a great variety of infringement activities, including both direct and indirect forms of expropriation that are not regulated under supranational legal regimes. States have increasingly adopted “creeping” forms of expropriation and rights violationsFootnote 16 and asserted their sovereign right to regulate.Footnote 17 Moreover, MNCs’ daily operations engage not only with state agencies such as market regulators, licensing authorities, and tax administrations, but also with private actors like business partners, local suppliers, customers, and market competitors, among others. MNCs’ main (and sometimes only) legal recourse against contract repudiation by local suppliers or intellectual property theft by other firms is the local judicial system in the host country.Footnote 18

Therefore, it is important to examine the conditions under which authoritarian courts can provide meaningful legal redress for MNCs’ diverse grievances stemming from either private or public actions. Just as the political controversies and structural limitations of ISDS mechanisms do not preclude their utilization by MNCs,Footnote 19 the inherent weaknesses of authoritarian judiciaries should not entirely discourage MNCs from seeking local litigation in host countries. As long as MNCs still see value in using local legal channels to resolve disputes and defend their interests,Footnote 20 the commitment problem posed by host states can be addressed such that it does not totally erode investor confidence.

We argue that, in front of dependent judges susceptible to outside pressure, foreign firms’ unique political resources can influence court rulings. MNCs may even enjoy significant, systematic adjudicative advantages if they can induce susceptible host courts to issue rulings in their favor. We also empirically demonstrate that MNCs actively use such “bad” institutions in host countries to protect and advance their business interests.

Connections, Partnerships, and Lawsuit Outcomes

Private firms can take advantage of their relationship-based resources to exert influence over public institutions.Footnote 21 Research has shown that MNCs can enjoy a myriad of nonmarket privileges by co-opting political agencies to receive preferential regulatory treatment and shape government policy.Footnote 22

Our study highlights the role of dependent courts in institutional rent-seeking.Footnote 23 We suggest that foreign firms’ nonmarket capabilities have important implications for analyzing their interactions with weak judiciaries in overcoming the commitment problem posed by host states.Footnote 24 Here, we focus on how foreign firms benefit from their political assets in navigating authoritarian legal systems and managing political risk. In particular, we discuss and compare two different types of political relationships that drive MNCs’ litigation outcomes in courts lacking judicial independence: personal political connections and corporatized political partnerships.

Non-market Advantages and Authoritarian Judiciaries

While weak institutional environments entail greater uncertainty around the de facto functioning of the institutions, they also present unique opportunities for multinational corporations if these firms can exploit such institutional weaknesses to receive regulatory protection and rent-seeking opportunities.Footnote 25 In response to adverse policy changes in the business environment, capable firms can tap into their political resources for policymaking access and influence. In an effort to overcome the commitment problem in FDI, MNCs seek to lower both political risk and contractual risk: the possibility that local public or private actors will overturn, alter, or reinterpret their agreements with foreign enterprises. Crucially, research shows that firms’ nonmarket capacities may allow them to craft “side deals” with political actors for special contract terms or individualized exceptions to adverse changes to any existing arrangements.Footnote 26

The authoritarian judiciary can be an important entry point for political influence and regulatory rent-seeking, given its lack of de facto independence. Therefore, when investing in authoritarian developing economies, foreign firms may take advantage of such political biases in adjudication to shield themselves from predation. Meanwhile, in such economies the success of litigation depends on the types of political ties and resources the MNC has.Footnote 27 In the context of domestic firms’ commercial litigation, Xu finds that the political nature of litigants’ ties to the ruling regime shapes lawsuit outcomes.Footnote 28 Likewise, when it comes to MNCs’ litigation in host-country authoritarian courts, we argue that the type of political capital MNCs develop and use in host countries is crucial for lawsuit success.

Conventional research on the value of government–business connections has focused on ad hoc exchanges of favor built on personal ties—a common form of corruption in authoritarian regimes.Footnote 29 In the case of litigation, however, both the plaintiff and the defendant have incentives to use their political capital to influence the rulings of vulnerable judges. Here it is important to distinguish between different types of political influence.

The extent to which an authoritarian judge conforms to the demands from each side's political patron is a function of the judge's relative commitment to different political interests. Judicial politics scholars have shown that authoritarian courts often serve as instruments of governance and control for the ruling regime.Footnote 30 The power of authoritarian courts is underinstitutionalized and highly contingent on the will of the political leadership, subject to curtailment at the discretion of political leaders.Footnote 31 Therefore, authoritarian judges exercise significant judicial self-constraint, especially when a case impinges on core regime interests. For example, Solomon argues that, in the Soviet era, a defining feature of the Bolshevik approach to the administration of justice was the preference for loyalty over expertise.Footnote 32 In the case of China, Xin He suggests that the CCP's core interest in maintaining its power and leadership dictates and shapes the regime's legal and administrative practices.Footnote 33 Meanwhile, Wang shows that the political interests of the authoritarian regime and the commercial interests of foreign investors can be well aligned when it comes to fostering investment inflows and economic development.Footnote 34

In the case of commercial lawsuits, the regime has a vested interest in securing favorable rulings for state-affiliated entities. We suggest that such adjudicative favoritism is a form of judicial rent-seeking that results in substantial financial awards for state-affiliated litigants.Footnote 35 Authoritarian judges tend to pay only lip service to political connections based on merely personal ties.Footnote 36 Exchanges of personal favors may not secure meaningful victories because these ad hoc, informal inducements are not strong enough to override judges’ commitment to upholding core regime interests when they weigh personal favors against their commitment to regime stakeholders.

On the other hand, formal corporate partnerships with the state can induce the dependent judiciary to serve shared interests. In authoritarian regimes, judges tend to be more attentive to business interests of direct concern to the state, and their institutional commitment is not easily swayed by enticements based on personal favors. Thus corporate partnerships between MNCs and the state result in institutionalized, sustainable adjudicative advantages for the joint enterprises. Corporate partnership ties between MNCs and regime insiders can structurally align a foreign firm's objectives with the state's interests. As a consequence, the authoritarian state will help the foreign investor shape the “rules of the game.”

Political Partnerships and Institutional Advantages

An effective corporate structure to co-opt state actors as stakeholders in the foreign firm's commercial success is a JV partnership with state-affiliated actors. This is a mode of market entry that builds ownership ties with host-government authorities, which help reduce institutional obstacles and manage political uncertainties. In particular, we emphasize the value of establishing JV partnerships with SOEs as a way for foreign firms to influence the operation of weak judiciaries and to capture institutional rents.

Forming JV partnerships with local actors is a common practice by MNCs around the world to mitigate investment risk. For example, evidence suggests that corruption tends to shift firms’ ownership structure toward JVs. Smarzynska and Shang-Jin observe that, for foreign firms operating in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet economies, the possibility of forming a JV rather than a wholly owned subsidiary increases with the level of corruption.Footnote 37 Likewise, Uhlenbruck and colleagues find that foreign firms adapt to the pressure of corruption via entry into JVs.Footnote 38 They show that MNCs use contracting and partnering as adaptive strategies to participate in markets where corruption threatens their equity ownership. Moreover, analyzing a sample of Japanese investors’ ownership decisions in the US, Chen and Hennart report that Japanese companies facing higher market barriers in the target industry are likely to choose JVs over wholly owned subsidiaries.Footnote 39

This evidence indicates that JV partnerships have unique advantages as investment vehicles for foreign corporations,Footnote 40 particularly in weak and uncertain institutional environments.Footnote 41 Local partners’ political and other proprietary resources help MNCs obtain business opportunities and protect investor rights in restrictive regulatory environments. Therefore, MNCs’ choice of entry mode tends to conform to the regulatory and competitive pressure in the host-country environment.Footnote 42 Evidence shows that MNCs with cooperative entry modes, such as JVs, enjoy lower investment risk than wholly owned subsidiaries.Footnote 43 Further, when the perceived legal and regulatory uncertainty is high, MNCs are less likely to convert from JVs to wholly owned enterprises, even if they have the option to do so.Footnote 44

MNCs may face a trade-off in forming JV partnerships. Partnering with capable local firms helps reduce political hazards, but perhaps at the expense of increased contractual hazards, including managerial conflict, expropriations, and intellectual property infringement by their domestic partners.Footnote 45 We assume that, for MNCs that have kept JVs as their mode of operation, managers have calculated that the benefits of such partnerships outweigh the potential costs. The total number of JV enterprises in China was not monotonously decreasing during the sample period (2002 to 2017)—it was actually steadily increasing from 2012 to 2017 (Figure 1). The proportion of JV enterprises among all foreign-invested projects was approximately 35 percent in 2002 and 24 percent in 2017.Footnote 46 The relatively consistent pattern suggests that JV partnership remains an attractive corporate structure for MNCs, considering all its benefits and risks. Henisz also shows that MNCs can adjust their relative exposure to political versus contractual hazards by choosing to hold majority or minority equity interest in partnerships.Footnote 47

FIGURE 1. Total number of joint ventures and wholly foreign-owned enterprises in China

The political resources of the local JV partner are particularly crucial for MNCs operating in authoritarian regimes. Unconstrained governments can be as predatory toward private domestic firms as they are toward foreign firms, if not more so.Footnote 48 MNCs cannot reliably mitigate political hazards posed by an unchecked state by partnering with local private firms that are also vulnerable to asset seizure and discriminatory tax and regulatory enforcement. They need partnerships with local firms that are tied to the regime's economic welfare; this will align foreign and state interests. Corporate partnerships with regime insiders give foreign investors a strong form of local linkage that helps them structurally overcome, and even exploit, the host country's institutional deficiencies.Footnote 49

Chinese SOEs are commercial entities that represent state interests, and their ownership structure allows powerful political actors to be stakeholders in their performance.Footnote 50 SOEs participate in market activities while acting as the corporatized embodiment of regime insiders’ interests.Footnote 51 Leutert shows that the leaders of core central SOEs are usually on a one-way street promotion to executive positions in the central government, provincial governments, or other central SOEs until their retirement, unlike the revolving-door careers of other types of Chinese state officials.Footnote 52 Relatedly, in post-Soviet Russia, the assets of Soviet-era SOEs were transferred through privatization to “insider oligarchs” close to the core Russian leadership.Footnote 53 Insider oligarchs and politically influential business elites have enjoyed privileged market status in Russia, similar to the dominant positions held by Chinese SOEs.Footnote 54 In particular, these powerful actors may favor weak public institutions that allow them to gain from rent-seeking opportunities and alternative rights-protection mechanisms such as corruption and relationship building.Footnote 55

Thus we argue that the strength of an MNC's political partnership depends on the type of partner and the form of the tie. JV partnerships with SOEs can address the commitment problem posed by an unconstrained state better than conventional political ties. Such business alliances offer MNCs links to the ruling regime that not only reduce investment risk but also shape adjudicative outcomes in a systematic way. The SOE partnership directly involves state interests, so the host state becomes a stakeholder in the joint enterprise's performance. The domestic judiciary, which is susceptible to external political interference, is induced to deliver material legal benefits to actors associated with the ruling regime. This type of institutional rent-seeking provides significant market advantages for MNCs that are connected to regime insiders, at the expense of other less connected litigants.

The value of a subservient judiciary has been mentioned in the comparative politics literature, although its implications for international political economy remain under-explored. Scholars have shown that domestic private firms that are political insiders are more willing to litigate in Chinese courts.Footnote 56 Evidence from Russia also suggests that businesses have a strong demand for using legal institutions to protect property rights even when state institutions are ineffective or corrupt.Footnote 57 Moreover, Lambert-Mogiliansky, Sonin, and Zhuravskaya find that firms’ benefits from bankruptcy proceedings in Russian commercial courts are shaped by the quality of the regional judiciary and the political power of regional governors.Footnote 58 In both established and unconsolidated democracies, business actors may prefer subservient courts and captured regulators to more independent institutions.Footnote 59

As a type of institutional rent-seeking scheme, SOE JV partnerships co-opt the state as a stakeholder in the firm's success and incentivize the state to internalize the foreign investor's interests. This corporatized relationship exploits dependent courts and results in judicialized privileges and systematic benefits for the collective enterprise. In this way, the politically risky environment may provide profit opportunities for foreign firms as domestic institutions are enlisted to serve their joint interests. Thus a dependent judiciary may become a vehicle for rent-seeking that locks in and institutionalizes MNCs’ market privileges.

Conventional channels of political connections, characterized by ad hoc, expedient types of personal exchange, are a weaker determinant of litigation success for MNCs.Footnote 60 Compared with SOE JV partnerships, non-ownership types of political ties with the authoritarian regime grant only limited, shallow forms of lawsuit success. This is because corrupt exchanges with authoritarian judiciaries still face a commitment problem: judges subject to external interference may not fully deliver on their promises. Dependent judges face political pressure from both the plaintiff and the defendant and will try to balance and prioritize political demands from the two sides. Therefore, the key determinant of lawsuit outcomes is which party can more strongly incentivize the judge to consistently attend to their side's demands. In the absence of strong incentives of judicial commitment, authoritarian judges may engage in conciliatory tactics in response to conflicting legal requests.Footnote 61

Lacking a deep commitment to either side's interests, judges may choose to superficially recognize the plaintiff's demands without satisfying their substantial claims against the defendant. Judges are under more political pressure when the litigant represents the vested interest of the regime than can be brought by exchanges of personal favors. In this respect, SOE JV partnerships reflect deeper and more credible involvement of the state in advancing the collaborative enterprise's interests. Thus authoritarian courts subservient to state–business alliances are more likely to vigorously uphold the JV's interests, rather than merely paying lip service to the legal merits of the litigants’ claims as courts normally do for other connected clients. SOE JV partnerships can exert a systematic influence over judicial outcomes, securing and locking in the state–business partnerships’ institutional advantages and overriding political connections based on personal ties.

Therefore, we hypothesize that JV partnerships with SOEs deliver greater political value and adjudicative advantages in authoritarian courts than common types of political connections. Specifically, we test the following hypotheses regarding the relationship between MNCs’ political resources and their litigation outcomes in host-country judiciaries.

H1 (political-partnership mechanism) All else equal, joint ventures between foreign firms and host state-owned enterprises are more likely to obtain substantial lawsuit victories than other types of foreign firms.

H2 (political-connections mechanism) All else equal, MNCs with personal political connections are more likely to obtain superficial lawsuit victories than foreign firms without political connections.

These two mechanisms are not mutually exclusive; they can function together in the adjudication process. Nonetheless, ceteris paribus, we expect the political-partnership mechanism to have a more pronounced impact on judicial outcomes in authoritarian systems than the political-connection mechanism. In later sections, we examine the explanatory power of the two mechanisms both separately and simultaneously.

A New Litigation Data Set

To examine MNCs’ performance in using local courts to assert and protect their rights when the host country lacks judicial independence, we construct a new data set on MNCs’ lawsuit activities in China. In 2013, to increase judicial transparency, the Supreme People's Court of China started to require all levels of courts to publicize judgment documents online within seven days of judicial decisions.Footnote 62 The court established and maintains an online database, China Judgment Online,Footnote 63 which contains court rulings in all levels of Chinese courts since 1996.Footnote 64 We used these legal records to construct our data set.

Concerns might be raised about selection bias in publications from a repository such as this one. For example, perhaps Chinese courts lean toward publishing rulings that appear impartial and professional. We offer three reasons to discount such concerns in this case. First, based on our own reading of hundreds of the documents, many of the records are of poor quality in terms of both writing proficiency and legal reasoning. Some are not even complete. There does not appear to be a stringent screening or censorship process prior to publication. Second, even if a bias toward publicizing “better” documents exists, the bias would be against finding the expected differences in the adjudicative decisions for different types of litigants, resulting in a harder test for our hypotheses. Meanwhile, if Chinese courts wish to project a foreign-enterprise-friendly image by uploading documents that predominantly favor MNCs, we should see MNCs overwhelmingly winning the lawsuits but this is not what we observe. Third, front-line judges presiding over foreign-enterprise-related cases told us in interviews that uploading these legal documents is a tedious, technologically cumbersome, and time-consuming administrative task. Judges and clerks struggle to find time for it. They are not strongly motivated to upload these records, much less to selectively upload only the “good” ones.Footnote 65

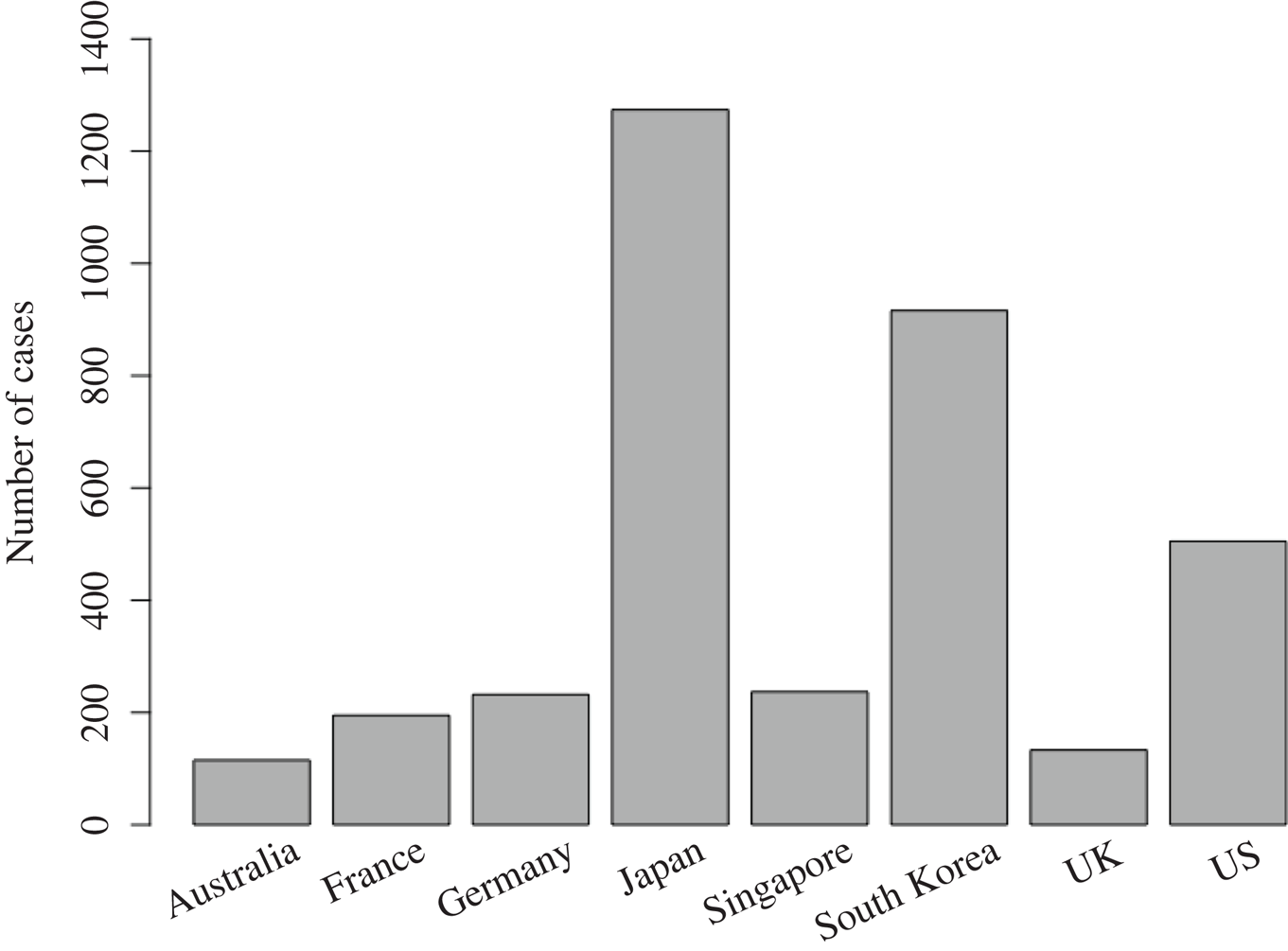

We web-scraped legal documents involving foreign litigants in Chinese courts from China Judgment Online, and then obtained corporate information about the litigants from various sources. We searched for all cases where a foreign company is one of the litigating parties, either as the plaintiff or as the defendant. In this project, we focus on some of China's major FDI-origin countries in various regions: Australia, France, Germany, Japan, Singapore, South Korea, the UK, and the US.Footnote 66 Given these countries’ dominant profiles in China's inward FDI, firms from these countries should also be involved in the great majority of foreign-related cases in Chinese courts.Footnote 67 As an improvement over existing research on ISDS that focuses on disputes between foreign investors and host governments, the new data set enables us to also examine legal disputes between MNCs and private actors in the host economy.

Empirical Strategy

We conduct both descriptive and regression analyses to test our theory. The primary outcome of interest is the ruling outcome for the plaintiff who brings a claim before the court. We measure lawsuit outcomes in three ways. First, we code whether the court's legal arguments and findings uphold the plaintiff's claims or reject them. We check whether the court expresses clear support for or mostly favorable opinions toward the plaintiff. Second, we consider whether the plaintiff pays lower court fees than the defendant. In China, judges usually charge the party they rule against higher court fees and expenses than the party on the winning side.Footnote 68 Thus the relative allocation of court fees indicates which side has the upper hand in the lawsuit.Footnote 69 Third, we look at the monetary compensation awarded to the plaintiff. Following the tradition in the corporate lawsuits literature,Footnote 70 we code whether any positive amount of monetary compensation is awarded to the plaintiff. We also consider higher thresholds for victory by looking at whether the plaintiff was awarded at least a quarter, half, or all of their claim.Footnote 71

The dependent variables use both subjective and objective measures. While judges are often unequivocal in their opinions of litigants’ claims, some rulings have mixed and vague messages that require closer reading by the coder to reach consistent and unambiguous conclusions. Therefore, the first measure entails more subjective understanding and interpretation of the court's judgment. Meanwhile, a judge's explicit support for the plaintiff's claims does not always translate into satisfactory compensation to the injured party. The more objective measures of monetary compensation aim to capture the adequacy of legal remedies.

The main explanatory variable is the corporate structure of the MNC. To identify JV partnerships between MNCs and SOEs, we first check whether the corporate entity is registered as a JV with the Chinese regulatory authority, the State Administration for Industry and Commerce (SAIC). As a specific type of JV, the entity is further coded as SOE JV if the MNC's JV partner is an SOE or if the MNC has a state agency as its majority shareholder.Footnote 72 We expect SOE JVs to be more effective in shaping judicial outcomes and inducing judges to issue favorable rulings and large monetary awards. The partnership itself is a political signal to judges that they need to bend the relevant rules and procedures and probably even accept regime insiders’ dictation of the terms of judgment (although, admittedly, we cannot directly observe such maneuvers, which occur behind closed doors).

We contrast our theory, centering on corporate–political partnership, with the conventional view of politicized litigation, which emphasizes litigants’ personal political connections. We empirically test our argument against the alternative view of the state as a mere “helping hand” in greasing the judicial wheels and obtaining favorable judgments. To measure whether a firm is politically connected, the main analyses rely on a broad definition of personal connections based on both board memberships and firms’ participation in government-led projects. We also show results using a narrower definition of politically connected personnel in board memberships.

We follow convention in checking whether the MNC's board includes any individuals with prior working experience in the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), the local or central government, the military, or SOEs.Footnote 73 These relationships are characterized by the management's personal ties, and their values are invoked on an ad hoc basis. Considering the extensive role of the government in China's socioeconomic landscape, we also code a firm as politically connected if it has participated in any social or economic projects led or promoted by the Chinese government.Footnote 74 Studies demonstrate that participation in these projects is a strategic choice by firms to create networking opportunities and build political relationships.Footnote 75

One may argue that participation in government-led projects is more of a consequence than a type of political connection, or that experience with the military or SOEs is not the same as experience with the CCP or the government. To address these concerns, we also consider a refined, narrower measure of political connections, using board members’ prior working experience in the CCP and government only (excluding the military and SOEs).

Unlike SOE JV partnerships, where the state is a direct stakeholder, the state does not hold direct business interests in personal, non-ownership types of political connections. By including the indicator of political connections in the regression models, we also account for a potential selection bias wherein politically connected firms may be more likely to use the courts. It is a common belief that “who you know” is a significant determinant of firms’ use of authoritarian legal procedures.Footnote 76 By controlling for litigants’ political connections, we aim to demonstrate a distinctive mechanism of political partnership, beyond the conventional notion of political connectedness.

To address other potential inferential challenges to identifying how MNCs’ political capital affects lawsuit outcomes, we include a set of control variables at the lawsuit and litigant levels, including plaintiff's home country, industry of operation, court location (province), case type, ruling year, ruling procedure, and opponent nationality.Footnote 77 These control variables address endogeneity concerns that some other features of the litigant or the lawsuit may be related to both the ruling outcome and the likelihood of establishing political ties. Although observable information on these lawsuits is limited, we have taken into account common confounders in estimating the effect of corporate political endowment on lawsuit outcomes.Footnote 78

First, firms from certain countries may be more likely to establish JVs with SOEs than firms from other countries, because of differences in their home countries’ political-economic systems.Footnote 79 Economies with state-led development models may predispose their MNCs to more actively pursue partnerships with SOEs, and these MNCs’ home states may also help them obtain more favorable legal settlements through diplomatic or other channels. Thus, we include a set of dummies for all the home states of the MNCs.

Second, there could be “forced joint ventures” in certain sectors. China's industrial policy requires foreign firms to establish JVs with domestic firms as a prerequisite for market entry in certain industries. To address such industrial heterogeneity, we include industry fixed effects for the MNC's industry of operation, using the Chinese classification for industry groups.Footnote 80 For example, one such category is Research and Development of Science and Technology. Including the sector indicators mitigates the concern that forced JVs may be more prevalent in technology-intensive industries. Moreover, since many of these restricted industries are dominated by SOEs that enjoy various benefits and privileges,Footnote 81 in the online supplement we examine the effects of SOE JV in state-dominated sectors versus other sectors separately.

Third, we consider the administrative heterogeneity between geographic regions in China. Some regions are more dominated by SOEs than others, and their local governments provide various protection and support measures for foreign firms. Therefore, we include dummy variables for all the province-level localities where the adjudicating courts are located.Footnote 82

Fourth, SOE JVs could be more likely to engage in types of lawsuits that award disproportionately large amounts of compensation to the plaintiffs, as a result of particular legal principles and their application. Thus we include dummies for case types (civil, criminal, administrative, enforcement-related, and intellectual property). We also include dummies for the adjudication procedure of the lawsuit: whether the case is a first instance, a second instance, or a “retrial, retrial review, or trial supervision” case. These procedural controls take into account the different kinds of claims, and hence the comparability of ruling outcomes across cases.

Finally, in cases with an MNC plaintiff we consider whether the defendant is also a foreign firm because SOE JVs may target other vulnerable foreign firms, although the number of such cases is small (277). In all models, we also incorporate year fixed effects to account for the evolving political and economic status of SOEs in the Chinese economy. Thus our results are not biased due to unique temporal features associated with different administrations.

We also perform an exact-matching procedure, in which we match on a set of observable confounders to identify the effect of political ties. Then we run logistic regressions on the matched data set. This test aims to further alleviate the concern that SOE JVs may be systematically different from other MNCs in some observable ways that correlate with the ruling outcomes.

We also acknowledge the possibility of litigants’ self-selection into lawsuits—that is, certain types of firms being more likely than others to use the judiciary. Given the lack of observable information on MNCs that choose not to litigate in Chinese courts, we cannot directly investigate this possibility. However, theoretically, we suggest that the direction of such a selection bias is likely to be negative. The negotiation process before litigation is similar to the bargaining stage before a war. The bargaining model of war in international relations indicates that it is efficient for conflicting parties to settle their disputes in the bargaining stage, rather than taking additional costly actions.Footnote 83 Analogously, MNCs with stronger political ties may have the resources or other means to resolve their disputes in more rewarding ways prior to escalating to courts. Therefore, this study is more likely to underestimate than to overestimate the effect of SOE JV partnerships on lawsuit success. Put differently, if there were no self-selection into lawsuits and if more SOE JVs profiting from nonjudicial channels instead chose to litigate in Chinese courts, the estimated effect of SOE JVs on litigation success would be even larger.

Statistical Results

Descriptive Results

The compiled data set consists of 3,730 cases involving at least one foreign enterprise.Footnote 84 The distribution of lawsuit filings is skewed in time (Figure 2). Most of the foreign-related lawsuits are reported in recent years, particularly after 2013. Part of the reason is that the judicial transparency reform initiative started to require the publication of all legal documents in 2013. Given the temporal limitation of the judicial transparency requirement, our data set is more representative of litigation patterns in recent years. We include the entire period in the main analysis, controlling for year fixed effects in all regression models. We also separate the cases into pre-2013 and post-2013 periods for a robustness check. Our findings hold in the post-reform period.Footnote 85

FIGURE 2. Lawsuits in the data set involving foreign multinational corporations in Chinese courts, by year

Figure 3 displays the distribution of MNC origin countries in those cases. Japanese and South Korean firms are frequent participants in Chinese judicial proceedings.Footnote 86 US companies have also been involved in 530 coded lawsuits. In UNCTAD statistics on investor–state disputes, the US appears only seventeen times as the respondent state and 190 times as the home state of the claimant.Footnote 87 Notably, none of these cases involved the Chinese government or Chinese firms. Thus, in comparison, the volume of foreign-related disputes resolved in Chinese domestic courts is considerable and should not be overlooked.

FIGURE 3. Lawsuits in the data set involving foreign multinational corporations in Chinese courts, by country

Table 1 reports the summary statistics of MNCs lawsuit outcomes in China. Interestingly, across all measures of lawsuit outcomes, the average plaintiff win rate is higher when MNCs sue domestic entities than the other way around. However, while MNCs are more likely to obtain supportive judgments from the court, the favorable rulings do not always translate into substantial monetary remedies.Footnote 88 The opinions favor plaintiff MNCs more than half the time, but award substantial compensation much less often. Only in 31 percent of all claims pursued by MNCs against domestic entities did the MNC receive any pecuniary compensation, and more substantial financial awards are even rarer than this. Likewise, domestic firms seeking reparations from foreign firms are more likely to score a superficial lawsuit victory than any meaningful compensation.

TABLE 1. Plaintiff win rates

Note: F, foreign firms; D, domestic firms.

The statistical evidence is consistent with the qualitative evidence we obtained from interviews with officials at the American Chamber of Commerce in Shanghai. They said that MNCs may be reluctant to resort to Chinese courts for dispute resolution because the sanctions imposed on offenders are usually too small to deter future violations. MNCs are not awarded sufficient damages, even if they “win.”

In the online supplement, we also examine two particular types of cases. The first is administrative cases, which can be regarded as the domestic equivalent of investor–state disputes in international forums. We observe that MNCs actively use domestic courts to sue host government agencies (781 cases),Footnote 89 although the winning percentages are even lower than in other types of cases: MNCs win favorable judgments in approximately 29 percent of the cases, and receive compensation in only 4 percent. The second type is intellectual property rights infringement cases. While intellectual property courts are expected to enjoy greater independence because of judges’ technical expertise and other institutional guarantees of judicial professionalism,Footnote 90 MNCs enjoy only superficial forms of rights protection in these cases as well.Footnote 91

Table 2 reports a preliminary test of our hypotheses relating MNCs’ political capital to lawsuit outcomes. A noteworthy finding is that foreign firms that have entered JV partnerships with SOEs enjoy substantial adjudicative advantages. The p-values for the two-sample t-tests indicate that, compared with other types of MNCs, SOE JVs are more likely to receive favorable rulings in terms of financially rewarding compensation, but not necessarily supportive judgments. In more than 30 percent of cases, the compensation awarded to SOE JVs is at least the claimed amount. Significant differences in average win rates across corporate structures highlight the importance for foreign firms in China of having ownership ties with state actors. Moreover, the results also indicate that JVs with private Chinese firms do not enjoy similar superior litigation performance, compared with the average MNC. If anything, private JVs actually perform worse than other types of MNCs for all substantial outcomes. Thus, it is the nature of the JV partner, instead of the JV partnership per se, that matters. Foreign firms with conventional political connections also outperform general MNCs only in terms of the shallow measure of adjudicative outcomes, which stands in contrast to SOE JVs’ more substantial judicial advantage.

TABLE 2. Case outcomes

Notes: MNC, multinational corporation; JV, joint venture; SOE, state-owned enterprise. P-values for two-sample t-tests comparing each type of firm with all other types are in parentheses.

Moreover, the differences in win rates are unlikely to be driven by SOE JVs’ pursuing smaller claims than other types of MNCs. In fact, on average, SOE JVs request more compensation than other MNCs, although the difference in means between the amounts for SOE JVs and those for connected MNCs is not statistically significant (Table 2). Another thing to notice is that, on average, SOE JVs are less likely than foreign firms to file administrative lawsuits as the plaintiff.Footnote 92 Considering that state agencies are the defendants in administrative lawsuits, this pattern is also consistent with the view that, on average, SOE JVs are more successful than other MNCs in co-opting the state.

Overall, these descriptive results provide preliminary evidence that market entry modes are important for MNCs to overcome and even exploit adjudicative biases in courts susceptible to political influences in authoritarian regimes.Footnote 93 Incorporating state actors as stakeholders in a commercial partnership helps the MNC take advantage of weak institutions and shape discriminatory decisions by subservient judges in favor of the allied entity. This type of partnership can better secure state commitment to investor protection and create institutionalized rent-seeking opportunities for foreign firms. The systematic advantages and benefits go beyond the conventional ad hoc political exchanges based on merely personal relationships.

Main Regression Results

In the main analysis, we use logistic regressions to estimate the effect of MNCs’ political assets on each of the six measures of lawsuit outcome.Footnote 94 Table 3 shows the results in three panels. Panel (1) examines the political-partnership mechanism, where we estimate the effect of being an SOE JV after controlling for a fixed set of case- and firm-level variables. JV partnerships between MNCs and Chinese SOEs are significantly more likely to win lawsuits than other types of corporate structures, across all measures of litigation success. The effect of SOE JV is not only statistically significant but also substantively meaningful. Table 4 shows the marginal effects in terms of changes in predicted probability.Footnote 95 We find that adopting a JV partnership with an SOE makes an MNC 10.6 percentage points more likely to obtain a favorable judgment, 15.6 percentage points more likely to pay lower court fees, 11.5 percentage points more likely to receive non-zero compensation, 16.8 percentage points more likely to receive at least a quarter of its claim, 16.7 percentage points more likely to obtain more than half of its claim, and 7.2 percentage points more likely to have its claim fully satisfied. Considering foreign firms’ average win rates, as reported in Table 1, the marginal effect of SOE JV on lawsuit success is substantial.

TABLE 3. Lawsuit outcomes by multinational corporation's type of political capital

Notes: Robust standard errors clustered by province are in parentheses. + < .10; *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

TABLE 4. Changes in predicted win probability

Note: MNC, multinational corporation; SOE, state-owned enterprise; PC, political connection; pp, percentage points

In panel (2), we look at the explanatory power of the alternative mechanism, focusing on personal types of political connectedness. We use both broad and narrow definitions of political connections to measure personal state–business ties. Across both measures, the plaintiff's political connections lead to more favorable court opinions, yet without substantial reparations. Neither measure is a statistically significant predictor of substantial compensation (more than one-quarter of claims), which is consistent with our theoretical expectation. Thus, the plaintiff's personal political connections are only a weak predictor of nontrivial lawsuit success, compared with a foreign corporation's structural ownership ties with the state.

Next, in panel (3), we include both soe jv and political connections to compare the explanatory power of these two mechanisms. The effects of litigants’ political connections remain similar to the pattern in panel (2), with political connections maintaining its statistical significance only for the shallow outcome of favorable court opinions.Footnote 96 In comparison, soe jv, as an indicator of the foreign litigant's corporatized political capability to affect adjudicative outcomes, significantly helps the plaintiff obtain meaningful remedies.Footnote 97 The coefficient sizes become even larger for the more substantial outcomes in panel (3). Turning to Table 4, on average, an SOE JV partnership increases the likelihood of lawsuit success by 7.2 (favorable judgment), 14.7 (lower court fee), 11.3 (compensation > 0), 18.2 (compensation ![]() $> {1 \over 4}$), 20.2 (compensation

$> {1 \over 4}$), 20.2 (compensation ![]() $> {1 \over 2}$), and 8.9 (compensation ≥ full) percentage points, respectively. In contrast, MNCs with personal political connections generally do not perform much better in court (in monetary terms) than MNCs without such connections. This is true for both broad and narrow measures of personal connections.Footnote 98

$> {1 \over 2}$), and 8.9 (compensation ≥ full) percentage points, respectively. In contrast, MNCs with personal political connections generally do not perform much better in court (in monetary terms) than MNCs without such connections. This is true for both broad and narrow measures of personal connections.Footnote 98

Notably, as panel (4) of Table 3 shows, JV partnerships with private firms suffer from significant adjudicatory discrimination in monetary compensation, though they are more likely than the average foreign firm to win a superficial victory. This is consistent with existing scholarship on the “political pecking order” in China's “state capitalism,” where foreign and local private firms have relatively low market status.Footnote 99

As a whole, the results support our theory that government–business relationships based on personal ties have limited effects on judges’ rulings regarding MNCs. Political connections may help foreign firms obtain only trivial forms of victory in court. In contrast, SOE JVs enjoy substantial adjudicative favoritism because the state is an interested party to the JV. The state, with a direct stake in the performance of this collective business, has incentives to create institutional advantages for foreign firms. Such a political partnership induces domestic institutions to deliver systematic judicial benefits to the JV, often in the form of substantial compensation.

Additional Tests

Considering the Defendants

Our theory implies that a plaintiff's influence over dependent courts is conditional on the defendant's political ties. When the defendant leverages personal connections to pressure the judge, the MNC plaintiff's claims may not be satisfied without countervailing political influence of its own. In other words, the commitment problem induced by dependent judiciaries under authoritarian rule leads to a low baseline win rate for MNCs litigating against actors with some political clout. It is in such circumstances that we expect the political value of SOE JVs to be most substantially realized. Thus we expect the effect of soe jv to be more pronounced when an SOE JV litigates against a politically connected defendant. A positive interaction coefficient between soe jv and the defendant's political connections will provide strong evidence that a corporate partnership with the state can more effectively overcome the commitment problem. We expect soe jv to be most effective when the court is susceptible to both litigants, that is, when the opponent has personal political connections. In this way, the institutional advantage of SOE JVs under dependent judiciaries is manifested through its resilience to the opposing side's ordinary political influence.

Table 5 presents the results of interacting the plaintiff's soe jv status with two types of political ties for the defendant. In terms of favorable court opinions, soe jv performs better when litigating against an unconnected defendant (that is, defendant pcs = 0), and defendant pcs significantly decreases the plaintiff's chance of receiving supportive arguments from the court (panel (1)). However, when it comes to substantial compensation, the advantage of soe jv is more pronounced when the defendant enjoys political connections. The effect sizes are larger when the plaintiff leverages its soe jv status to litigate against a party with the ability to influence court decisions. The negative sign of defendant pcs suggests that without strong state support the plaintiff faces a significant threat from commitment problems. Put differently, the importance of ownership ties with the state is best manifested under threats of commitment problems, when the court might be compromised by the opposing side.

TABLE 5. Effects of political partnership conditional on the commitment problem

Notes: SOE, state-owned enterprise; JV, joint venture; PC, political connection. Robust standard errors clustered by province are in parentheses. + < .10; *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

If the defendant is not an SOE JV (that is, defendant soe jv = 0), then the MNC plaintiff enjoys significant adjudicative advantages across different ruling outcomes if the plaintiff is an SOE JV (panel (2)). Nonetheless, if the defendant is also an SOE JV, then the plaintiff SOE JV largely retains its advantages, although there is now more uncertainty regarding substantial compensation. Thus the judicial privilege for the plaintiff SOE JV is less pronounced when the defendant is also an SOE JV, compared with the situation where the defendant has only ordinary political connections.

Taken together, Table 5 shows the unique value of SOE JV as a corporate structure for triumphs in authoritarian courts against politically connected firms. SOE JV plaintiffs are more likely to secure meaningful victories when the defendants are not SOE JVs. Moreover, litigation against other SOE JVs entails higher adjudicative risk than against firms with non-ownership types of political ties. Overall, the results highlight the importance of the corporatized alliance with the state in overcoming the commitment problem posed by the lack of rule of law in authoritarian regimes. The SOE JV partnership, as an ownership structure and investment vehicle, induces the dependent judiciary to help the MNC establish institutionalized market privileges through legal means. Common types of political connections are not as reliable as ties established through shared ownership stakes in extracting nontrivial concessions from susceptible courts. The results also underline the complexity of the commitment problem when authoritarian judiciaries can be influenced by both sides of the lawsuit and are not as committed to legal principles as they are to the relative political leverage of the litigants.

Matching

To further alleviate concerns about confounders that may cause foreign firms to both form SOE JV partnerships and win lawsuits (that is, selection bias in the adoption of SOE JVs), we perform an exact matching procedure. We match on all the observed control variables in our data set that may simultaneously affect corporate structure and ruling outcomes. We use the matchit function in R to preprocess the lawsuit data set.Footnote 100 The matched data set produces better covariate balance between SOE JVs and other types of plaintiffs. Then we use logistic regression to analyze the matched data set.Footnote 101

Panel (1) in Table 6 shows the effect of SOE JV after perfectly matching plaintiffs on a set of potentially confounding covariates. soe jv remains positive and has a statistically significant effect on most measures of lawsuit success, even when using this conservative estimation technique. As a comparison, we also conduct the same exact-matching procedure for plaintiffs with personal political connections. The null effect of political connections on meaningful ruling outcomes is also largely consistent with that seen in Table 3. Overall, the matching results confirm the main findings: political partnership is a robust determinant of lawsuit success, especially for substantial monetary rewards. Ordinary political connections, in contrast, do not significantly contribute to more rewarding litigation outcomes.

TABLE 6. Exact-matching results

Note: + < .10; *p < .05; **p < .01.

Robustness Checks

We conduct additional analyses to test the robustness of the findings of the main analysis. First, since the data from before the 2013 judicial transparency reform may suffer from sample selection bias, we focus on the post-2013 period. Second, we conduct a subsample analysis focusing on the coastal provinces in Eastern China with greater FDI exposure, to assess regional heterogeneity. Third, we revisit only the cases where MNCs are the plaintiffs. Fourth, we incorporate additional firm-level control variables in the regression models, including the firm's China experience, its size, and whether it is publicly traded. Fifth, since the results of logistic regressions are hard to interpret substantively, we use ordinary least squares regressions to facilitate interpretation of the results. Sixth, we conduct a nearest-neighbor propensity score matching procedure as a supplement to exact matching. The results of these analyses are available in the online supplement. Our main findings hold throughout.

Conclusion

As large volumes of FDI flow into developing countries with weak institutions, it is important to understand how foreign investors protect their rights and assert interests in host countries without independent judiciaries. This article focuses on institutional arrangements within host countries, an understudied mechanism of cross-border dispute resolution compared with supranational investor rights protection mechanisms beyond host countries.

We construct a novel data set on MNCs’ litigation activities in China to investigate how foreign-related lawsuits are adjudicated in authoritarian courts. We find that foreign firms frequently resort to Chinese domestic courts to resolve disputes and seek legal remedy for a variety of issues. Theoretically, we examine the conditions under which foreign investors may succeed in these local legal venues. We argue that JV partnerships between MNCs and SOEs can enlist the authoritarian state as a stakeholder in the success of the collective commercial enterprise. This corporate structure aligns regime interests with foreign investors’ interests and thus incentivizes the state to create judicial privileges and rent-seeking opportunities to institutionally benefit the JV. Our findings point to an underexplored mechanism of investment protection where MNC-SOE JV partnerships, as a form of political alliance, induce authoritarian judiciaries to safeguard their joint interests. Such political partnerships secure substantial adjudicative favoritism and help MNCs overcome the commitment problem posed by an unconstrained authoritarian state more effectively than firms’ personal political connections.

Our study contributes to the emerging research agenda that recognizes domestic judiciaries as part of the “global community of courts” dealing with cross-border dispute resolution issues.Footnote 102 It uncovers the value of authoritarian institutions to foreign investors by disentangling different types of state–business ties. An implication of the findings is the value of dependent courts to foreign firms. Conventional wisdom maintains that the value of judicial independence and the rule of law lies in the power of courts to constrain government behavior.Footnote 103 However, MNCs’ political ability to generate rents from weak institutions may shape their political preferences and their choice of institutional venues for dispute resolution. If MNCs expect preferential legal treatment from susceptible local courts, they may prefer these local forums to third-party adjudicative venues beyond the host country.Footnote 104 Foreign firms’ ability to shape host-government decision making may be one reason they have not been as resistant to pursuing domestic litigation as scholars have assumed.Footnote 105 MNCs’ effective political engagement with dependent courts can also explain the inconclusive empirical relationship between regime type and firms’ perception of political risk.Footnote 106

Finally, we suggest that our theory is generalizable to other authoritarian regimes where the state plays an important role in the market economy and state-affiliated actors act on behalf of regime insiders and enjoy various benefits and privileges.Footnote 107 SOEs and their business partners receive favorable administrative treatment and access to institutionalized rent-seeking opportunities in many developing countries exhibiting features of state capitalism and crony capitalism.Footnote 108 The judiciary is a part of the state apparatus that can be enlisted to serve the interests of regime insiders as well as their partners and cronies. Authoritarian rulers can use their leverage over the judiciary to engage in systematic rent-seeking schemes with their foreign partners behind a façade of judicial neutrality and legitimacy. As a response to such institutionalized corruption, US legislators have been trying to target US MNCs’ “corrupt bargain[s] with the Chinese Government or the CCP to gain or retain market access or receive any other benefit” through a revision to the US Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, considering that these bargains “are more valuable to the Chinese Communist Party than any monetary bribe.”Footnote 109 We intend to continue this line of inquiry in future projects.

Data Availability Statement

Replication files for this article may be found at <https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/PJGT3R>.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material for this article is available at <https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818322000297>.

Acknowledgments

For helpful input, we are grateful to Chris Castillo, Minqi Chai, Mark Copelovitch, Jennifer Gandhi, Haosen Ge, Yue Hou, Nan Jia, Reed Lei, Siyao Li, Chuan Liu, Lisa Martin, Jon Pevehouse, Eric Reinhardt, Miguel Rueda, Ken Schultz, Weiyi Shi, Jeff Staton, Jessica Weeks, William Winecoff, Boliang Zhu, participants in the 2019 annual meetings of the American Political Science Association, the International Political Economy Society, and the Midwest Political Science Association, and at workshops at Nanyang Technological University, Stanford University, the University of Georgia, the University of Michigan, the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, the University of Oxford, the University of Wisconsin–Madison, and Washington University in St. Louis, as well as the anonymous reviewers and editors at International Organization. We also thank Jingwei Gao, Yani Gao, Yingdi Lei, Wenting Li, Zipei Li, Shihao Liang, Xinran Ma, Julia Wang, Qing Wang, Yumeng Xu, Tsz-yan Yeung, Gang Zhang, Qiuqi Zhang, and Erpu Zhu for excellent research assistance.

Funding

This research is partially supported by the Ministry of Education, Singapore, under its Academic Research Fund Tier 1 (022637-00001). Frederick R. Chen acknowledges multiple research grants from the Department of Political Science at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. Jian Xu acknowledges generous financial support from Emory University.