Introduction

On June 14, 2019, the head of Turkey’s supreme court of cassation, İsmail Rüştü Cirit, made a political statement in support of the ruling Justice and Development Party’s (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi – AKP) involvement in restoring cultural heritage sites, long criticized by the opposition as cultural whitewashing. The high court judge posed in front of Khlat Cemetery, an act that he described as a stance against traitors of Turkey. Such pro-ethnic/nationalist posing in front of ancient monuments has become a staple of high-ranking officials in Turkey in need of impressing the political leadership. The choice of place for uttering these words as part of a nationalist rhetoric, Ahlat (Խլաթ in Armenian), has long been an archaeological site (Figure 1), and most recently it was also chosen as the location for the summer palace commissioned by President R. Tayyip Erdoğan to be built to commemorate the movement of Turks from Central Asia into Anatolia with the Battle of Manzikert in 1071.Footnote 1 Ahlat is a Turkified name of the location in East Anatolia; originally it referred to the Armenian homeland called Hlat. Such hypervocal propaganda of state-sponsored nationalist mythmaking resonates with the internationally renowned Turkish film director Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s (b. 1959) title of his latest film Ahlat Ağacı/Hlat Tree (2018).Footnote 2

Figure 1. Khlat tombstones.

Film critics unanimously stated that the title of the film has a dual meaning (Aytekin Reference Aytekin2021, 14; Barış Reference Barış2020; Liktor Reference Liktor2020, 119). In fact, ahlat and Khlat might have multiple meanings: ahlat ağacı is a tree endemic to contemporary Turkey, Armenia, and Georgia. This tree has an irregular, crooked shape and its fruits are also irregular in shape. Hence, the title of Ceylan’s film in English translation misses the subtlety of the original title (Khlat, denoting the pre-Manzikert Armenian homeland in Anatolia as well as the wild pear) and the double entendre of the term “Klat.” This irregularity is attributed to the irregularity of the Anatolian landscape and metaphorical irregularities in the lives of the three generations of male characters in the film (Saydam Reference Saydam2018).

In this article, we argue that through the lead character Sinan’s quest in the film en route to self-realization, Ahlat Ağacı attempts to unsettle the domineering presence of “myths of Gallipoli,” i.e. myths based on the Battle of Gallipoli (February 19, 1915–January 9, 1916) during World War I, in contemporary Çanakkale, including myths of militarism, nationalism, and capitalism in their interconnectedness to hegemonic masculinities. Ceylan attempts to construct a living and breathing space for contemporary characters as they seek paths for a hopeful future emancipated from the prevalence and oppression of such myths.

To illustrate our analysis of how the film points to the possibility of liberation from the oppression of domineering myths, we first introduce Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s oeuvre in the past two decades focusing particularly on the trilogy, in which Ahlat Ağacı is the ultimate film. Prior to an analysis of salient myths of Çanakkale throughout the twentieth century, we introduce a general theoretical discussion on myths, history, and fiction. The next section focuses on mythmaking on Çanakkale throughout the century in Turkey as it relates to Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s Ahlat Ağacı. In the latter sections, we analyze the possibilities of resisting hegemonic masculinities that are enmeshed with domineering myths on Çanakkale, underlining the precarity and, simultaneously, the prevalence of “hope” in the last scene of the film.

In the article, we do not concentrate on the actual Battle of Gallipoli (1915–1916) itself, nor do we question its significance during World War I. Our concern is more with the overarching/omnipotent presence of myths and memorials relating to the Battle of Gallipoli in present-day Çanakkale and the ways in which such monuments have been purposefully left out of Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s Ahlat Ağacı. Despite its preoccupation with the past in its reconstruction of historical memory, the film is set in the present of unease with the AKP government’s democratic backsliding, intensifying after the Gezi Park protests.Footnote 3 The selection of the city of Çanakkale in Ahlat Ağacı is of utmost significance, as the locations that Sinan roams through physically point to the Gallipoli Wars.Footnote 4 The memory of the Gallipoli Wars was rebranded during the AKP rule as a new touristic (geared toward the domestic and international market) and ideological marketing tool. Throughout the film, Sinan attempts to resist the commodification of memorials and memory both in his novel about the town and through his actions, while attempting to emancipate everyday people (including himself) from the haunting presence of memorials connected to the Battle of Gallipoli.

Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s trilogy: Once Upon a Time in Anatolia, Winter Sleep and Ahlat Ağacı

Previous critics have noted that Ceylan’s earlier films like Small Town, Clouds of May and Distant are part of a provincial town trilogy (Daldal Reference Daldal2023; Özselçuk Reference Özselçuk2022). We claim that Ahlat Ağacı is part of a new Land of Ghosts trilogy of films starting with Once Upon a Time in Anatolia and Winter Sleep dealing with post-memory and a subtly implied critique of the AKP regime in Turkey. According to Yanat Bağcı (Reference Yanat Bağcı2022, 194), Ceylan’s last three films show similar narrative and thematic qualities, employing long monologues. In his films, the choice of provincial characters, a minimalist storyline, involving a crime and a perpetrator, seem to be inspired by nineteenth-century Russian literati, including Chekhov, Dostoevsky, and Tolstoy (Mathew Reference Mathew2019).

In the past two decades, as one of the prominent transnational film directors of the new cinema of Turkey, Ceylan, much like his contemporaries, explored themes of nostalgia, alienation, inclusion of minorities, and, to a lesser extent, women’s voices. This new cinema also employed innovative methods of financing and production (government and internationally funded and distributed) as opposed to a more local and consumer-oriented Yeşilçam cinema of the 1950s–1970s (Arslan Reference Arslan2011; Dinç and Akser Reference Dinç and Akser2019; Suner Reference Suner2011).

Even though Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s earlier works have received substantial scholarly attention (particularly Clouds of May, Distant, Climates, and Three Monkeys), the trilogy including Once Upon A Time in Anatolia has not enjoyed the same publicity and has not been included in recent theoretical discussions (Cerrahoğlu Zıraman Reference Cerrahoğlu Zıraman2019; Diken et al. Reference Diken, Gilloch and Hammond2017; Raw Reference Raw2017; Wood Reference Wood2006). In fact, the significant historical and political contexts of the trilogy (Dudai Reference Dudai2019; Liktor Reference Liktor2020; Mathew Reference Mathew2019) have been dismissed. In 2011, his film Once Upon a Time in Anatolia won the Grand Prix; in 2014, Winter Sleep received the Palme d’Or. Ahlat Ağacı, nonetheless, did not receive as much media attention as the director’s previous filmic works.

Ceylan’s early films have also been personal, reframed in a staged way but performed by friends and members of his family in stark black-and-white cinematography. Such examples include Cocoon and Small Town (in black and white) and later Distant and Clouds of May (in color). As Daldal (Reference Daldal2017, 183) comments, “loathing all kinds of ‘fakeness,’ he [Ceylan] refrained from engaging professional actors in his films.” These films are almost memory texts that do memory work as “re-enactments of the past through performances of memory both in and with visual media” (Kuhn Reference Kuhn2010, 298). Ceylan used his hometown of Çanakkale and its immediate surroundings for personal and cinematic reasons. As an independent filmmaker at the beginning of his career, his hometown gave him easy access to locations and individuals he could utilize in his films. Based on his later success and starting with the film Three Monkeys (2008), Ceylan was able to use international and Turkish government support to make films with larger crews and with scripts and professional actors (Akser Reference Akser, Baltruschat and Erickson2015). Ceylan himself explains this new turn as something unexpected, that he discovered the possibilities a screenplay can open up for a director known for his desire for authenticity. After making four films based in different locations in Turkey, Ceylan came back to Çanakkale to film Ahlat Ağacı. In this film, Ceylan uses narrative techniques he did not use in his previous films. He employs empty landscapes as opposed to memorials and sites; and disappearing and dreamlike sequences featuring the main male character Sinan.

The first two works in Ceylan’s trilogy focus on characters wandering in the vast emptiness of the land in different parts of Anatolia, which is a metaphor for the quest for lost souls, starting with the film Once Upon a Time in Anatolia. The main characters in the film literally look for a dead man’s body hidden by a perpetrator. The three films share characters in search of truth through a very subtle metaphor achieved by the same topographic exposure and narrative techniques. The second film of the trilogy, Winter Sleep, signals displacement, evoking the pogroms against and the absence of the Greeks in the post-1922 period. Much like the Cappadocian caves which make up the film’s unique setting, Winter Sleep points to the absence of the peoples who inhabited Anatolia for thousands of years prior to the establishment of the Turkish Republic. The subtle exposure of the empty land or spaces point to the following questions: Who lived here before? Why is there all this emptiness? Such questions are not answered explicitly throughout the films but explored through subtle narrative techniques.

In Winter Sleep, characters are stuck in a land that was not theirs before. This situatedness or rather the status of being “stuck” in a home that was for centuries not just one’s home, but that of many now absent others, is also a theme endemic to Ahlat Ağacı. There are attempts made by certain characters in Winter Sleep to comment on this subjugation like the father played by Nejat İşler who chooses to burn all the money given by the hotel owner, defying the new landlords of the land. This symbolic gesture is a stance against the ultimate oppression of a capitalist society.

Navigations between mythmaking, history, and fiction

Prior to moving on to the analysis of the various ways in which Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s Ahlat Ağacı unsettles a few of the salient layers of mythmaking regarding the Gallipoli campaign, it is worth pointing out definitions of myth, history, and fiction that will be used throughout the article.

Myth could be defined along George Schöpflin’s taxonomical ordering, as creating “an intellectual and cognitive monopoly” and seeking “to establish the sole way of ordering the world and defining worldviews” (Schöpflin Reference Schöpflin, Hosking and Schöpflin1997, 19). More influential and powerful than the impact of “history,” myth has the potential to incite wars, bring about conflict or conflict resolution, form the basis for commemorations and rituals, shape textbooks and the theoretical frameworks of textbooks. Nationalist discourses could be carried to the status of myth; nationalist myths around the Gallipoli campaign, for instance, have been pervasive myths for decades in Turkey and have formed the basis for the monumentalization in Çanakkale.

Within a taxonomy of narratives that include myth, history, non-fiction, and fiction, myth has utmost authority, credibility, and societal impact. History and non-fiction also make truth-claims and have varying degrees of credibility and authority, less certainly than “myth.” Within this classification, fiction is different from the three other narratives. Fiction does not make truth-claims and does not enjoy credibility. If fiction, however, is elevated to the stage of myth, it might gain the same status of having authority, credibility, and impact. Hence, while narratives can be classified differently, there is room for mobility depending on their reception or depending on the changing political sentiments attached to them.

Different versions of this mythmaking exist for different segments of the Turkish society through textual and audio-visual incarnations. Depending on the ideological stance of the creators, these myths can come with Islamist or secularist overtones. The founding years of the Republic were witness to an Islamist narrative, opposing the secular/nationalist accounts of Gallipoli. The most powerful example is the poem by Mehmet Akif Ersoy, “To the Martyrs of Çanakkale,” that portrayed the Gallipoli campaign as a kind of resistance of the army of Muslims against the infidel during the war of independence until the early days of the republic (Yanıkdağ Reference Yanıkdağ2015). In the late 1920s, Mustafa Kemal, in Nutuk (Speech), presented himself as the singlehanded leader of the Greco-Turkish War, and it was not necessary to concentrate on the Gallipoli campaign in this version of national mythmaking which points towards an omission of this important battle. Akif’s religious call to arms did not find a place for itself in the secular narrative of Nutuk (for a discussion of Nutuk, see Adak Reference Adak2003).

In 2002, the AKP came to power, with an open admiration toward Ersoy and his version of Muslim martyrdom during the Gallipoli campaign. Islamist mobilization regarding Gallipoli appeared in the secular nationalist press in 2004 (Aktar Reference Aktar2020, 219). This evocation of Islamist interpretation of Gallipolu led to a serious backlash as a response from the secular nationalist cultural elite in the form of Tolga Örnek’s Gallipoli (2005), a docudrama with Jeremy Irons as the narrator. In the secular versions of the Battle of Gallipoli, in order to countermand the Islamist narrative, Mustafa Kemal’s leadership and heroism were depicted with hyperbole. Örnek’s film enjoyed a huge box office success when released and led the way for further fictional 1915 Gallipoli-themed films close to the centenary of the event in 2015. Another Gallipoli-inspired secular nationalist text was the best-selling historical novel, Diriliş: Çanakkale 1915, published in 2008 by the playwright Turgut Özakman. The book would later be made into a film and spawn a series of other nationalist films on the subject. To date, both versions of Gallipoli mythmaking, the Islamist and the secularist versions, exist concomitantly in a tensile atmosphere of contesting claims on their heroes.

Unsettling myths of Gallipoli

Gallipoli-as-myth is entrenched in Turkish nationalist historiography in various ways. First, similar to Australia and New Zealand, Gallipoli serves as the foundational national myth in Turkey in its multiple manifestations (Haltof Reference Haltof1993; Ziino Reference Ziino2006). Second, in the secularist version of the myth, only Turkish soldiers and their deeds of valor were prioritized. This version asserted that the military history of the Gallipoli campaign could be written in the context of the history of the Turkish army even though the soldiers in the Ottoman military forces and beyond were not all Turkish (Kut Reference Kut2022). Third, and most relevant to Ceylan’s film Ahlat Ağacı, is that myths of Çanakkale suppressed the narratives of other histories, voices, and events by claiming priority, particularly through mourning (of Turkish/Islamic martyrs) (Gezgin Reference Gezgin2019). Lastly, mythmaking regarding Gallipoli throughout the twentieth century in Turkey operated to oppress and silence the Armenian Genocide (Kaul Reference Kaul2018; Manne Reference Manne2007).

In Turkish historiography, starting from the 1930s, Ottomans were presented as ethnic Turks. As part of this process, the military history of World War I was Turkified and the Ottoman Imperial Army (Osmanlı Ordu-yi Hümayunu) was converted into the Turkish Army (Türk Ordusu) by historians. Subsequently, all ethnic groups, such as Kurds, Arabs, Georgians, and non-Muslim minorities, who were drafted into the army in 1914 were obliterated from this version of history writing (Aktar Reference Aktar2020, 215).

Further, as in most mythmaking, myths of Gallipoli employ national heroes. In secularist mythmaking on Gallipoli, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk’s heroic deeds are prioritized. Present-day Çanakkale is laden with pictures, portraits, statues, and other visual monuments (Figure 2) dedicated to the memory of war and the founding father Mustafa Kemal. In Ahlat Ağacı, Sinan’s novel, on the other hand, enables a further possibility that nationalist mythmaking and the Gallipoli myths deny: criticizing and exposing the flaws of the (founding) fathers. As military and national myths take hold of the present of the everyday lives of the Turkish nation, they oppress by eulogizing the nationalist fathers’ narratives. The film Ahlat Ağacı presents Mustafa Kemal Atatürk and the Gallipoli memorials in peripheral places or refuses to give them any place at all. This topographically revisionist memory act is another dimension through which Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s Ahlat Ağacı appropriates the “filmic present” from the grip of national mythmaking (Figure 3). The film does the opposite of heroizing its main male characters, Sinan and his father, İdris. Hence, Sinan and İdris become part of the repertoire of the everyday that the film puts in the foreground. The focus of the film Ahlat Ağacı is not on survivors or the descendants of the survivors, but rather on the culture of the remaining peoples in Turkey, and the inheritance and working through of nationalist myths as they are passed down from fathers to sons.

Figure 2. Martyr’s Monument in Gallipoli.

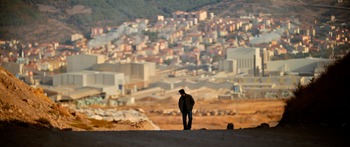

Figure 3. Sinan’s (Doğu Demirkol) wandering in the vast emptiness of the ghost city of Dardanelles rather than the monumentally nationalist version of the town. Looking back by the protagonist is a visual marker before key fantasizing scenes in the film.

The film parallels and affirms Sinan Karasu’s quest for the everyday in its own structure and enables the telling of the lives of everyday characters. These mundane characters include: the lottery vendor (milli piyango bayisi); İdris the loser, the father who squanders all his money; and drunkard Rıza who is the epicenter of a conflict that Sinan experiences in his quest to get financial support from a contractor (müteahhit). During the long scene with the contractor İlhami (Kubilay Tunçer), Sinan talks about his emphasis on the culture of everyday life in his novel and the contractor puts him down and attempts to shame him for offering to represent drunkard Rıza (Ahmet Rıfat Şungar) in his novel and not giving representative priority to the sacred martyrs of Çanakkale. The contractor adds that he cannot allow the most important and internationally renowned battlefield in the world to be missing from a novel that he is supposed to sponsor. Hence, the contractor criticizes Sinan bitterly for excluding myths of Gallipoli in his novel and refuses to offer funding for its publication. According to the contractor, the novel would not have market value anyway because “the only myth that sells is that of the Dardanelles.” The contemporary moment in Çanakkale wanes in comparison and, according to the contractor, is not marketable. In this lengthy dialogue, whereas his discursive adversary (the contractor) promotes the concept of martyrdom, vouching for homeland and Islam, Sinan tries to point out the meaninglessness of the glorification of mass death over a piece of land.

Moreover, throughout the twentieth century, the memorialization of Gallipoli has been hyped up to eradicate the memory of one of the seminal violent events in the history of Anatolia, the Armenian Genocide (1915–16). On April 25, 1915, the Allies landed at Gallipoli. However, just a day before, more than 250 Ottoman Armenian politicians and intellectuals were rounded up and deported to inland Anatolia. As has been noted, in the Turkish nationalist imagination, March 18, 1915 is the day when Turkish artillery stopped the mightiest Allied navy (Ziino Reference Ziino2006, 143). Since 2002, March 18 has been officially commemorated as the Day of Martyrs.

While in Turkey, the fallen soldiers at Gallipoli (1915) were commemorated and mourned throughout the century, around the world, April 24 was commemorated as the beginning of the Armenian Genocide. Since 1965, concomitant with important commemorations of the Armenian Genocide in the international context, Turkey has been hyping up the ANZAC Day commemorations (April 25) as a Turkish–Islamist spectacle/media event (see Fisk Reference Fisk2015; Hovhannisyan Reference Hovhannisyan2015). This particular emphasis on ANZAC Day entails downplaying the significance of the Armenian Genocide and impeding the most traumatic incidences of violence of the twentieth century from surfacing into collective memory. This state line has continued to date. The concluding section of our article illustrates that Ahlat Ağacı hints at this eradication – posing a glimmer of hope of coming into memory – with a technique quite endemic to Nuri Bilge Ceylan films, a twist at the very end (which also happens in Once Upon a Time in Anatolia). Hence, the last scene of Ahlat Ağacı poses a possibility for unearthing the silent past of the Armenian Genocide.

Sinan’s fictional/literary interventions

The stylistic choice to employ dialogue and monologue scenes (mostly of Sinan) gives the impression as if the film were a visual version of a novel. Sinan’s novel Ahlat Ağacı, on the other hand, is one of the various filmic and narrative devices that Ceylan uses as a way of working through the myths of Gallipoli. Sinan’s novel in the film is a subtle and multi-layered response to rescue contemporary Çanakkale from the hegemony of nationalist popular (pulp) fiction and film as well as secularist and Islamist mythmaking on Çanakkale.

The film Ahlat Ağacı follows Sinan’s quest to get his new novel also titled Ahlat Ağacı published. In his efforts, he encounters his father İdris’s moral decline, his uninterested mother Asuman and sister Yasemin, a corrupt local businessman, a disillusioned commercial author, and two anonymous Islamic preachers stealing apples from a tree. Sinan’s challenges in his relationship with his father are manifold: on the one hand, he has to overcome his father’s shadow of financial and moral loss, while also proving himself worthy of his father’s sacrifices in his attempt to give him the best education for a better life. In the end, Sinan finds himself trapped by society’s pressures and goes back to his parental land to help his father bring life to the very earth that might be home to an actual “Ahlat Tree.” Sinan’s persistent digging for water in the wild and rustic terrains of Çanakkale carries the double potential of giving life to wild pears (fertility in the wilderness) as well as that of unearthing and reinscribing the historical memory of lost/departed owners of the land.

The literariness of the dialogue is in line with the literary form he uses, i.e. the novel, to write his preferred version of his own life/memory as history. As it is narrated literally by its author Sinan in the form of a sales pitch to a plethora of characters in the film, the text of the novel points to the flaws of Sinan’s own father and to his generation and a previous one before him. The text defended by its author is described as an attempt to reinscribe present lives and contemporary life, simple existence, in an effort to rescue the everyday from the hegemony of myths of the Gallipoli campaign, the martyrs who are omnipresent in collective memory decades after the battle and the historical sites that dominate historical thinking.

In the film, Sinan’s double move, of writing the novel and attempting to realize his father’s dreams of finding water to give life to more wild pear trees, carries a significant emancipatory potential. As such, Sinan is liberated from the flaws of his father through the novel: he has communicated and forced his father to confront his flaws through a written text. Further, in the film, Sinan has not disowned but appropriated his father’s dreams and transformed them into ones that have meaning for himself. In the end, Sinan has started a quest that bespeaks neither reputation nor financial compensation: a humble journey on the road to rewriting history, reinscribing the presence of the disappeared former occupants and bringing productivity and life to barren lands. The inability of the father and the passive–aggressive stance by Sinan point towards the employment of new resistance towards the hegemonic masculinities in the film which will be discussed in the next section.

Resisting hegemonic masculinities

Cultural memory, as Astrid Erll (Reference Erll, Erll and Nünning2008, 389) puts it, “is constituted by a host of different media, operating within various symbolic systems: religious texts, historical painting, historiography, TV documentaries, monuments, and commemorative rituals.” Erll (Reference Erll, Erll and Nünning2008, 389) illustrates in detail how each of these media has specific ways of remembering, concluding that “fictions, both novelistic and filmic … create images of the past which resonate with cultural memory.” Following Erll’s approach to the mediality of cultural memory in film, we emphasize the significance of cinematic fantasizing in Ahlat Ağacı, which carries the potential of unsettling the collective amnesia brought about by mythmaking based on the Gallipoli wars. In fact, the entire film revolves around a quest to unearth what could be missing from these domineering myths of Gallipoli and their connections to the hegemonic masculinities that Sinan (the lead character) seeks to resist.

The film Ahlat Ağacı revolves around the leading character Sinan, who recently graduated from college in the big city. After completing his education, Sinan returns to his hometown of Çanakkale and oscillates between the latter and his grandparents’ village of Çan during the entirety of the film. Even though Sinan has received training to become a teacher like his father İdris, his sole aspiration is to find financial support to publish his recently completed novel.

Ahlat Ağacı is a testament that rejects the “triumph of collective amnesia” in favor of confronting traumas of the past. Such confrontations include Sinan’s quest to write his own personal history enmeshed in the account of the small town and his refusal to sell out to big money. Sinan embraces such difficult confrontations rather than further monumentalizing Gallipoli within nationalist frameworks. As a fictional character inside a fictional universe, he creates his own personal fiction removing him from our reality as the viewers. Sinan decides to write a novel that tells his own personal history as opposed to other authors from the region writing on the monumental victory narratives that exclude ordinary people like him and his father. By writing his own personal/family version of history, Sinan is actually counter-writing meta-narratives of Gallipoli. Sinan returns to his hometown with hope after following his father’s footsteps to become a teacher but instead finds a broken home. He is neither able to find employment, nor secure financial support to publish his novel. His crush is also about to get married to a wealthy tradesman. Until the last scene of the film, hope, as it relates to multiple dimensions of his life, be it the personal, professional, and artistic, evades him.

In Ahlat Ağacı, the main male character Sinan, particularly through his personal narrative of confronting the legacies of Gallipoli, is not in accordance with the various hegemonic masculinities of his small town. In fact, Sinan is not alone. His father İdris and grandfather Recep all lead us into the realm of the absurd, in their discordance with national mythmaking, ideal and militarized heroes of the nation, capitalist victors, and/or heterosexual predators. Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s means of unsettling hegemonic masculinities which unite nationalism, militarism, capitalism, and heteronormativity includes employing characters in his films who cannot perform in contexts defined as “successful” given such norms. Further, the three generations of men that Ahlat Ağacı depicts, including Recep, İdris and Sinan in their Sisyphean labor of digging into the well at the end of the film, attempt to bring life to the wasteland and unearth the silenced traumatic pasts of Anatolia. Such unearthing with the aim of bringing life, both biological and historical, also presents an alternative, the dimension of hope, to otherwise absurd characters.

Throughout the film, using lengthy dialogue or moments that grow on the viewer, Ceylan’s narrative approach is indicative, not openly expressive but hinting at its stance via particularly evocative scenes. Aslı Daldal (Reference Daldal2013, 186) notes that Ceylan has:

… a political tone in an apolitical guise … Ceylan hardly talks about anything political. But by rejecting the present culture of consumption and excess through humble and slowly proceeding silent stories, by painfully trying to avoid the lie of cinema through minimal editing, sound, camera jobs, and acting, by radically challenging the established norms of popular cinema through totally personal works, Ceylan is political in his first films, if not with “what” he says, but with “how” he says … it.

Following Daldal’s interpretation, we argue that both Ceylan’s story and how he chooses to tell it point to the disguised politics of memory and gender.

Through Sinan and his interaction with other men, the film presents a personal journey, however flawed and failed, to tackle/unsettle nationalist narratives. The film is a profound reflection on Sinan’s suffering as gendered trauma (because of his disobedience to codes of hegemonic masculinity) and his quest to start his personal odyssey.

Hence, the film points at a crisis of hegemonic masculinity, unsettling most of the mythic layers with which it is enmeshed, including militarism, nationalism, heteronormativity, couplism, and capitalism.

In a plethora of Ceylan’s films, lead male characters struggle against the norms of hegemonic masculinities, constructed at the societal level as well as at local levels, such as small towns. According to the formulation of hegemonic masculinity by Connell and Messerschmidt (Reference Connell and Messerschmidt2005, 838),

there is a circulation of models of admired masculine conduct, which may be exalted by churches, narrated by mass media, or celebrated by the state. Such models refer to, but also in various ways distort, the everyday realities of social practice.

Schools, peer groups, workplaces, and, in the Turkish case, the military service for men are places where young boys are oriented toward obeying this hegemonic masculinity. These models “express widespread ideals, fantasies, and desires. They provide models of relations with women and solutions to problems of gender relations” (Connell and Messerschmidt Reference Connell and Messerschmidt2005, 838).

Sinan’s primary frustration is about the ideals associated with teachers and teaching in Turkey. Since its inception in 1923, the Turkish Republican education system has presented teachers as guides to (Western) civilization (Durakbaşa and Ilyasoğlu Reference Durakbaşa and Ilyasoğlu2001). Teachers, starting with Mustafa Kemal who posed as the head teacher of the nation, guided the nation on the road to progress, civilization, and European ideals. In small towns, teachers connect the liberal, European values of urban spaces to the locals of the rural. Teachers have a vital role in disseminating the idealized values of the Turkish Republic in rural areas (Altınay Reference Altınay2004).

Ceylan’s Ahlat Ağacı employs the characters of İdris, the mediocre and destitute schoolteacher, and Sinan who cannot find a job as a teacher to illustrate the unattainability of the role-model of this ideal teacher figure who is so enmeshed in the national imaginary. Both characters unsettle the expectations embedded in the successful teacher model; Sinan cannot get appointed as a teacher throughout the film but also does not want to fulfill his father’s ideal. Both characters are only frustrated by the position of the teacher: the father, primarily because it leaves him financially destitute; the son Sinan, because it does not lead to the realization of his dreams of giving narrative voice to the everyday realities of Çanakkale.

Sinan’s second frustration is what it entails to be “famous” as a novelist in a small town. The scenes of his encounter with the “prominent best-selling novelist” in his small town bespeak racism and nationalism. In the second dialogue-laden attempt to defy capitalist logic, Sinan engages this well-known novelist in a bookstore during an author’s book-signing session. In an almost Dostoevsky-style tirade between the novelist and Sinan, the economic logic of cultural production is also challenged by the lonely and independent writer. Sinan proposes that fiction is pivotal as a narrative of memory, delineating people’s lived experiences, whereas the famous novelist points to a very personal and materialist take on his craft. Sinan’s verbal altercation with the renowned novelist in the bookstore signals a dialogue-driven cinematic approach on Ceylan’s side. In this significant scene, Ceylan visually references books on the shelves of the bookstore, such as Hitler’s Mein Kampf which became a bestseller in Turkey a few years after the AKP took power (Nefes Reference Nefes2015), hence condemning fascist monumentalism. The bookstore is depicted in alliance with ultranationalist fascism, as Hitler’s portrait is displayed near the cashier (Figure 4). Sinan is portrayed in his difference from the framing devices in the bookstores, as a young aspiring writer facing a commercial novelist with the portrait of Franz Kafka – a well-known Jewish author of modernism – standing between them. After this scene, the spectator is led to another path of possibility. Beyond the anti-Semitic, ultranationalist, fascist masculinities exhibited in the bookstore, and the commercial ambitions of the male author whose books are showcased, a different type of masculinity has to be possible: Sinan exits.

Figure 4. Hitler is framed at the bookstore during the film’s confrontation scene.

Sinan’s novel is replete with a multiplicity of themes and connotations that are relevant to the allegory of reworkings of perpetrator masculinities (Taylor et al. Reference Taylor, das Nair and Braham2013). If only this generation’s fathers and grandfathers could read their stories and suggestions for unsettling the historical construction of the past! Sinan’s parricidal Oedipal uprising against the father’s legacy is not punished but rewarded: İdris not only reads Sinan’s novel which blatantly criticizes the father’s flaws but accepts this criticism. To take this a step further, İdris takes pride in his son’s novel. Toward the end of the film, Sinan takes out İdris’s wallet which lacks money or proper identification papers. The only significant document that is tucked into the inner pockets of the wallet is a newspaper article boasting Sinan’s picture and announcing the publication of his novel. In lieu of material possessions or identification papers, the most essential possessions and identity of the father translate into a confrontation with his own flaws and a rewriting of Çanakkale as a present-day site, with the sorrows, trials, and tribulations of its contemporary residents from the perspective of Sinan as a young, aspiring Çanakkale-based minor writer.

The fact that Sinan has written a novel, rather than an autobiography or non-fiction (for instance, on everyday life in Çanakkale), has resonance with the overall allegory of the working through of a mythical Islamist/populist narrative and mythmaking in general. Sinan’s quest for writing fiction illustrates that he is comfortable with the “constructed and fictional world” that he has created. For his delineation of contemporary Çanakkale and the ordinary lives and suffering in the city, he is not claiming hierarchically domineering genres, such as “history” or non-fiction.

Emre Çağlayan draws attention to Ceylan’s previous work such as Uzak where similar themes of silence and exposition of urban space as a mental desert can be found. He comments that Ceylan’s “male leads are lonely wanderers, whose desire for women is unmatched by their voiceless disposition and their inability to use language, which are classic symbols of castration” (Çağlayan Reference Çağlayan2022, 324). However, the wandering of the characters in Ahlat Ağacı is no longer aimless as Sinan (and Ceylan) chooses the locus of the wanderings, i.e. the exact sites of Gallipoli, to evoke ghosts or former inhabitants of the region. Sinan chooses to bond with his father and grandfather in his trials to come up with a different variant of masculinity, but these turn out to be failed attempts at homosocial bonding. The unsuccessful bonding is replicated with the author (in the bookstore) and with the two preachers. Also, the silence or speechlessness is no longer an issue, as Sinan is among the most vocal and verbally expressive characters that Ceylan has ever written. The irony is that his very literary monologues to pursue others fail miserably.

Sinan’s next frustration is encountering Hatice and his failure to attract her as a man for longer than the duration of a clandestine kiss and the exchange of a few melodramatic words. Albeit brief, this is a pivotal scene that combines space, gender, and fantasy. In the first few moments of their encounter, Sinan declares to his secret crush Hatice that he wants to become a starving writer, rather than being a schoolteacher, a profession chosen by and imposed upon him by his parents. Hatice seems to be impressed that Sinan has completed college and will become a professional with job prospects. She laments her inability to leave their small town and get an education herself. Instead, she has accepted a marriage proposal to an older man just because he is wealthy. Sinan attempts to revive a moment of intimacy with Hatice. She was never his girlfriend but his best friend’s former girlfriend. The two share a fantasy moment, under a tree reminiscent of the biblical scene of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden. For a single moment, (imagined) memory becomes a reality as Hatice kisses Sinan, then true reality strikes back. The idyllic (sinful) scene is almost magical, with wind blowing through Hatice’s hair in reverse slow motion, freezing time, desire, and subordination to a chronotope. Sinan’s attempts at resuscitating past memories of innocence and happiness and longing for her fails miserably. Here he discovers that Hatice might have feelings for him, but she succumbs to economic realities of the small town in Anatolia. The trade-off to rejecting the possibilities of a wealthy position is that Sinan loses the love of his life to an older (and more affluent) man, the jeweler. Hatice makes her point about love silently, attempting to refuse to give in through smoking a cigarette, and savoring a (biting) passionate forbidden kiss with Sinan. Sinan is powerless to get Hatice’s attention for himself and to prevent this unwanted marriage. Cinematically, the use of slow motion around Hatice is a technique that minimizes the burden of the present, assigning Sinan’s beloved the qualities of a living statue, almost in the guise of a Greek goddess.

Throughout the film Ahlat Ağacı, when reality proves to be too grim, Sinan finds solace in daydreaming fantasies. He fantasizes about his own death as we encounter a scene with him hanging above the well or his father’s death while he is sleeping on the ground surrounded by ants. Death in the film is peaceful and serene and brings rebirth and rejuvenation in subsequent scenes. In another fantasy escape, Sinan is seen inside the gigantic wooden model Trojan Horse statue, a wistful throwback to an imagined narrative of antiquity (Figure 5). However, Sinan rebels against this one-on-one embracing of Greek mythology, as he picks up a mythical female figure, symbolizing Helen (plausibly Hatice), attached to the bridge he is crossing and throws it into the sea (Figure 6). In present-day Çanakkale, the bridge exists in reality in that very same location, but the statue was digitally inserted into the film – a first ever in a Ceylan film, making the scene all too symbolic and important. Throwing Helen into the waters below is an act that involves rejecting a type of masculinity (as manifested by Menelaus and Paris) based on the appropriation of the woman (Helen/Hatice) and rejecting war that is sought in the fight for appropriating the female body (the Trojan War). In this respect, appropriating Helen/Hatice (through violence or force) is not going to shape the way Sinan imagines masculinity. As Sinan liberates himself from the desire to possess Hatice/Helen, so the Trojan Horse, both as a toxic gift of betrayal and as the signal to the onset of war, conquest, and bloodshed is emptied of its haunting presence.

Figure 5. Personal fantasy replacing the Turkish nationalist monumentalism of his everyday reality.

Figure 6. Time freezes in Sinan’s fantasies.

Those male characters in Ahlat Ağacı, who seem to be the epitome of “success” according to ideals of hegemonic masculinity under neoliberal capitalism, are not idealized in the film but rather ironically portrayed. The town mayor, for instance, claims he removed the office door to impress the residents of his small town about how accessible his office was to the public. In a subsequent scene, we see that he is not the fair and ideal boss he boasts about as he starts mistreating and slavishly overworking his assistant. A similar ironic depiction concerns the contractor who boasts of a great library, encompassing a wide array of books. A close-up scene shows that his “great library” constitutes a single bookshelf. Even though such men are not portrayed as “ideal” figures of masculinity, Sinan is still threatened by them. When the contractor does not financially endorse Sinan’s novel, this frustration enhances the latter’s misery. However, Sinan’s response is not to embrace such positions of money and power. He does desire to ward off anxieties (having no financial prospects) or feelings of inferiority (not getting the woman he desires, etc.) but not through force, nor through embracing militarism, nationalism, or power. Such discouraging encounters do not break Sinan’s resolve to continue his own process of self-actualization. A century after the Battle of Gallipoli, the main character of Ahlat Ağacı observes and opposes the exploitation of the land via narrow-minded and greedy developers, and the destruction of all natural resources, humans and animals alike. Sinan, while being vocal in his criticism of all men pushed to being identical, continues his unique journey toward self-realization without succumbing to the ideals of hegemonic masculinity.

Conclusion: unearthing traumatic pasts …

Ahlat Ağacı is the third film by Nuri Bilge Ceylan in a series of covertly metaphorical films about the search for identity and lost memories by the wandering main characters.

Ultimately, the digging in the well at the end of the film presents a “coming home” after the characters’ incessant wandering. The well, however, is not a bright and promising metaphor for a nation. Those who get inside the well remain unseen, like repressed memories of the land. The film Ahlat Ağacı not only takes its name from an irregularly shaped fruit tree but from the ancient locale of Hlat where recently a new presidential palace has been built and the history of the region is presented in terms of a Turkish–Islamic synthesis. This way, through topographical and literary devices, the film brings the Armenian homeland of Khlat into the “present” of Çanakkale, a city that only remembers its past through the Gallipoli myth. In doing so, we argue that the film hints at the intentional forgetting of the Armenian population of Anatolia and the amnesia around the Armenian Genocide.

Contemporary Turkish cinema abounds with examples of similar issues of loss of memory, replacement of populations of Anatolia, leading their characters to explore the deserted lands: Gelecek Uzun Sürer (Future Lasts Forever, d. Özcan Alper, 2011) and television series such as Şahsiyet (Persona, d. Onur Saylak, 2018) establish this through metaphors. Such loss of memory and a quest for a novel construction of masculinity are present in Ahlat Ağacı as Sinan challenges the father even when he feels obliged to continue the father’s legacy. This film also poses questions of perpetrator masculinities intersecting with issues related to a nationalist ethnicity. The central metaphor for this interaction becomes the well that the three major male characters have been digging for three generations. Sinan’s quest within the well where he sees his own reflection is a bold rejection of nationalist heroism of the above-the-ground monumental symbolism. The film proposes a humble quest with no witnesses for this quest, the only exception being the spectators of the film. Sinan is so lost in the depths of the well that his father thinks him dead. Ceylan uses the father character for a reversal in thinking, i.e. reversal in historical thinking. If fathers could read their sons’ version of history, then the nationalist denialist version of history would stand a chance for revision and transformation.

If Once Upon a Time in Anatolia was a confession, the unraveling of a corpse, an autopsy that revealed the method of murder, and the unsettling of the audience’s comfortable belief in a past of innocence, Ahlat Ağacı could be hinting at a method of expressing and confronting this inherited past of violence.Footnote 5 Ahlat Ağacı refers to both ends of a well where hopeful observers, the peasants in the village, try to dig, and get rid of hard rocks to have water flowing through the land.

Sinan’s father is known to have adamantly pursued such a quest. He moves to the countryside to live, enmeshed in memories in Sinan’s grandparents’ farm and both men start to dig deeper into the well. The well is part of the allegory: one can look up to the sky after digging deeper into its depths. In the end, Sinan himself goes down into the well which his father could not dig. Sinan is able to take the hard rock out after his transformation, entailing perhaps his liberation from the powers of authoritarian state, capitalist enterprise, and army. His rebellion is channeled into pure creativity of life, not just words in a novel but real life that matters in the midst of a thirsty land. Lost in the depths of the well, he reaches out to dig out not exclusively a past but the faint possibility of a hopeful future. As Sinan becomes invisible to the spectators, and the last scene is ensconced in utter darkness, the only trace that remains with us is the sound of his incessant digging …

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a Newton Mobility Grant (2019–2020) from the British Academy. The authors would like to thank Zeynep Atakan for allowing us to use the high-resolution images.

Competing interests

None.