Compared with their majority counterparts, ethnic minority and migrant groups are at greater risk of mental health difficulties,1 particularly psychosis.Reference Leaune, Dealberto, Luck, Grot, Zeroug-Vial and Poulet2–Reference Jongsma, Turner, Kirkbride and Jones5 This excess risk is not observed in migrant groups’ countries of origin,Reference Dykxhoorn and Kirkbride6 nor can it be explained by diagnostic biases or genetic risk factors.Reference Morgan, Knowles and Hutchinson7 Interestingly, this elevated risk is context-dependent, such that minority group members living in neighbourhoods with a low proportion of their group are more likely to experience psychosis than those residing in areas where their group is well represented.Reference Anglin8 This association, termed the ‘ethnic’ or ‘group’ density effect, operates in a dose–response manner,Reference Boydell, Van Os, McKenzie, Allardyce, Goel and McCreadie9 holds after adjustment for socioeconomic deprivationReference Bosqui, Hoy and Shannon10 and is proposed to act as a buffer against social disadvantages experienced by minorities.Reference Das-Munshi, Bécares, Boydell, Dewey, Morgan and Stansfeld11 Most studies have focused on minorities classified by their ethnicity or migratory background, but poorer mental health has also been observed in minority groups defined by other characteristics, including sexuality,Reference Hatzenbuehler, Keyes and McLaughlin12,Reference Post and Veling13 political affiliationReference Saville14 and religion.Reference Murphy and Vega15 As the present review will include minorities grouped by other ‘non-ethnic’ social characteristics in addition to ethnic minorities and migrants, hereafter we will use the term ‘group density’ instead of ‘ethnic density’.

So far, there have been three reviews of the group density effect in psychosis,Reference Bosqui, Hoy and Shannon10,Reference Bécares, Dewey and Das-Munshi16,Reference Shaw, Atkin, Bécares, Albor, Stafford and Kiernan17 all of which examined associations in ethnic minorities and migrants. At present, it is unclear whether lower own-group density areas confer the same risk across different minority groups. The most recent meta-analysis found that ethnic group did not moderate group density associations.Reference Bécares, Dewey and Das-Munshi16 However, narrative reviews noted that studies examining pooled ethnic minority samples tended to report more consistent effects than studies assessing specific minorities, which yielded mixed results.Reference Bosqui, Hoy and Shannon10,Reference Shaw, Atkin, Bécares, Albor, Stafford and Kiernan17 Specific marginalised and minority groups have distinct social experiences, so investigating group density relationships in combined samples might mask important group differences.Reference Bosqui, Hoy and Shannon10,Reference Das-Munshi, Bécares, Boydell, Dewey, Morgan and Stansfeld11 Identifying heterogeneity in effect sizes between different minority groups, ethnic and otherwise, may elucidate potential causal mechanisms.Reference Schofield, Das-Munshi, Bécares, Morgan, Bhavsar and Hotopf18 More broadly, identifying moderators of this phenomenon is important for understanding the aetiological underpinnings of psychotic disorders and for providing targeted clinical and policy interventions for minorities.Reference Morgan, Knowles and Hutchinson7,Reference Bosqui, Hoy and Shannon10,Reference Bécares, Dewey and Das-Munshi16 In this review, we aim to conduct a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis of the group density effect in psychosis and examine potential moderators, particularly those associated with specific minority groups.

Method

We followed Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman19 and Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) guidelines.Reference Stroup, Berlin, Morton, Olkin, Williamson and Rennie20 The protocol for this review was pre-registered on PROSPERO (reference: CRD42019139384). Deviations from protocol can be found in Supplemental 1 of the Supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2021.96.

Search strategy

In May 2019, S.J.B. conducted electronic searches of four databases (PsycINFO, Web of Science, PubMed and CINAHL Plus). Searches were repeated in August 2020. We consulted with Bangor University's academic support librarian for the College of Human Sciences for assistance with designing the search strategies. The search strategies were piloted before the final search was executed. Each search utilised truncation and thesaurus tools to find related terms and enhance retrieval of relevant articles. The full list of search terms and an example search strategy for one database can be found in Supplementals 2 and 3. Below is an example of the organisation of search terms:

(A) population, e.g. Psychosis OR Psychotic OR Schizophrenia OR Bipolar

(B) ethnic density-related terms, e.g. ‘Ethnic density’ OR ‘Group density’ OR ‘Ethnic composition’ OR ‘Ethnic enclave’

(C) outcome measures, e.g. Incidence OR Prevalence OR Symptom* OR ‘Ultra-high risk’

(D) geographical terms, e.g. Neighbo* OR Municipal OR ‘Electoral ward’ OR ‘Output area’

A AND B AND C AND D.

Eligibility criteria

For the narrative review, we included any peer-reviewed primary study examining the group density effect in psychosis. For the meta-analysis, additional criteria were applied, as follows:

(a) primary epidemiological studies assessing a within-group density association, i.e. comparing psychosis risk within minority groups between different levels of group density

(b) geographical units averaged 50 000 people or fewer

(c) group density exposure quantified using census data or similar

(d) validated quantitative instrument(s) used to measure psychosis outcomes, including incident cases, psychosis experiences, prodromal psychosis or symptomatology

(e) studies reported odds ratios (ORs), incidence rate ratios (IRRs), hazard ratios (HRs) or relative risks (RRs), effect size measures and 95% confidence intervals (CIs)

(f) studies used multilevel modelling to account for non-independence of data

(g) studies adjusted for individual- and area-level confounds (minimally, age, gender and area-level deprivation).

Study selection and data extraction

Articles were exported to Mendeley citation management software. After removing duplicates, S.J.B. and C.W.N.S. independently assessed all titles and abstracts for eligibility and any papers that either author deemed relevant were carried forward to the next stage of screening. Kappa indicated substantial agreement between authors (k = 0.754).

Full texts of remaining articles were independently screened by S.J.B. and C.W.N.S., with 100% agreement regarding which studies should be included in the narrative review and meta-analysis components of the review. Uncertainties concerning eligibility were resolved through discussion or contacting authors where clarification was needed. Reference sections were hand-searched to identify any further papers. For potentially relevant articles that were not available in English, we assessed eligibility by translating the article or contacting the first author of the paper (Supplemental 4). Study characteristics and meta-data from included studies were extracted. Authors were contacted for additional data where necessary. For studies with overlapping data-sets, only the study with the largest sample was included in the meta-analysis. If samples were equally large, we included the study where group categories were most compatible with other studies.

Data analysis

A narrative review was conducted and studies meeting inclusion criteria were included in the meta-analysis. As group density studies often include dependent effect sizes – multiple samples (level 2) nested within studies (level 3) – we used ‘multilevel’ meta-analysis,Reference Van den Noortgate, López-López, Marín-Martínez and Sánchez-Meca21–Reference Harrer, Cuijpers, Furukawa and Ebert23 as implemented using the rma.mv function in the R package Metafor24,Reference Viechtbauer25 to appropriately control error rates.Reference Harrer, Cuijpers, Furukawa and Ebert23

Effect sizes with CIs were extracted from the fully adjusted models in each paper. As studies quantified exposure differently, we rescaled effect sizes to reflect decreases of 10 percentage points in group density. Effect sizes and CIs were then converted to their natural logarithmic form, from which log standard errors and sampling variances were computed. See Supplemental 5 for further information on how effect sizes were rescaled.

The three-level model was fitted to estimate the overall pooled effect size. To assess fit, we reran the analysis twice, holding the variance component of level 2 or level 3 constant.Reference Harrer, Cuijpers, Furukawa and Ebert23 Akaike information criteria for full and reduced models were compared to assess fit.

The overall pooled effect size comprised all samples. Separate pooled effect sizes were computed for groups defined by ethnicity or migratory background, minority groups classified by other characteristics, and neighbourhood studies only.

We additionally examined a priori hypothesised moderators and the effect of removing individual studies and samples on the pooled effect. For each moderator test, the most common grouping was used as the reference category. To derive subgroups, the 18-group self-ascribed classification system for ethnic groups used by the 2011 UK Census was used to allocate samples into ‘crude minority groups’ (the UK was the most common study setting). Subgroups for the ‘specific minority groups’ moderator test were informed by the most specific minority group categories reported by the authors of the studies. To assess the moderating effect of area sizes, we calculated area size quartiles using reported average area sizes. If average area sizes were not available, census data were used to derive an estimate. We also stratified data by the geographic unit used: lower super output area (LSOA) or smaller and all other area sizes.

We used a quality assessment tool developed for ethnic density studies specifically, which has been used in a previous reviewReference Bécares, Dewey and Das-Munshi16 (Supplemental 6). We additionally conducted GRADE assessments to evaluate the evidence for each psychosis outcome and crude minority subgroup (Supplemental 7).

Results

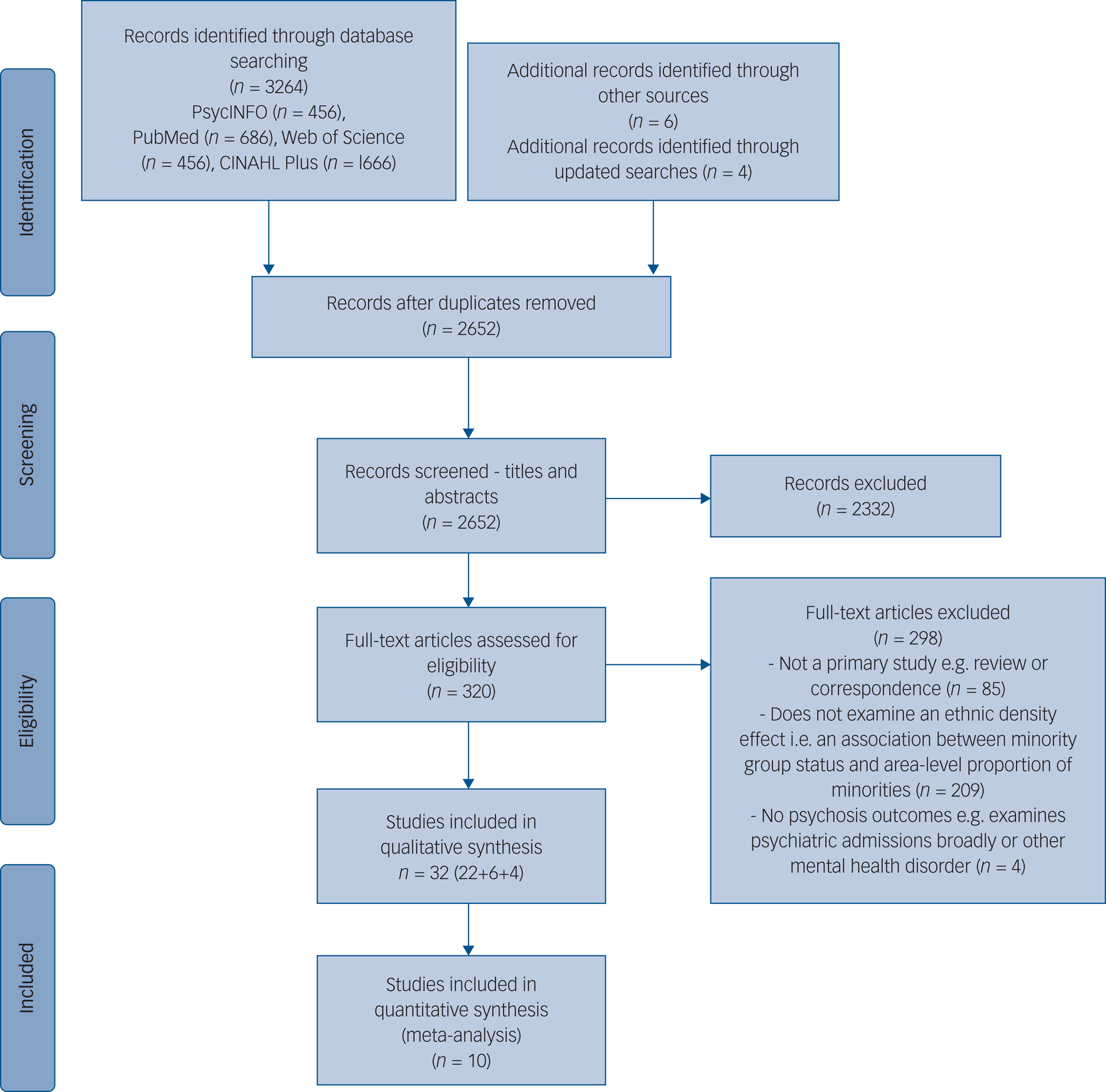

The search identified 2652 unique articles, and 32 studies were included in the narrative review (Fig. 1). Ten studies met inclusion criteria for the meta-analysis, comprising 75 samples. Each sample contributed <2% weighting to the overall pooled effect size (Fig. 2 shows the forest plot).

Fig. 1 PRISMA diagram outlining study selection procedure.

Fig. 2 Forest plot of the association between a 10 percentage-point decrease in group density and psychosis risk

Narrative review

Study characteristics

Fourteen studies (44%) were conducted in the UK,Reference Boydell, Van Os, McKenzie, Allardyce, Goel and McCreadie9,Reference Das-Munshi, Bécares, Boydell, Dewey, Morgan and Stansfeld11,Reference Schofield, Das-Munshi, Bécares, Morgan, Bhavsar and Hotopf18,Reference Kirkbride, Boydell, Ploubidis, Morgan, Dazzan and McKenzie26–Reference Kirkbride, Morgan, Fearon, Dazzan, Murray and Jones36 nine (28%) in The NetherlandsReference Eilbracht, Stevens, Wigman, van Dorsselaer and Vollebergh37–Reference Horrevorts, Monshouwer, Wigman and Vollebergh45 and four (13%) in Sweden.Reference Mezuk, Li, Cederin, Concha, Kendler and Sundquist46–Reference Terhune, Dykxhoorn, Mackay, Hollander, Kirkbride and Dalman49 Of the remaining five (16%), two were conducted in DenmarkReference Schofield, Thygesen, Das-Munshi, Becares, Cantor-Graae and Pedersen50,Reference Schofield, Thygesen, Das-Munshi, Becares, Cantor-Graae and Agerbo51 and one each in the USA,Reference Anglin, Lui, Schneider and Ellman52 CanadaReference Menezes, Georgiades and Boyle53 and Australia.Reference O'Donoghue, Yung, Wood, Thompson, Lin and McGorry54

The majority were retrospective epidemiological studies (n = 26, 81%).Reference Boydell, Van Os, McKenzie, Allardyce, Goel and McCreadie9,Reference Das-Munshi, Bécares, Boydell, Dewey, Morgan and Stansfeld11,Reference Schofield, Das-Munshi, Bécares, Morgan, Bhavsar and Hotopf18,Reference Kirkbride, Boydell, Ploubidis, Morgan, Dazzan and McKenzie26–Reference Kirkbride, Morgan, Fearon, Dazzan, Murray and Jones36,Reference Termorshuizen, Smeets, Braam and Veling39–Reference Veling, Susser, van Os, Mackenbach, Selten and Hoek42,Reference Mezuk, Li, Cederin, Concha, Kendler and Sundquist46–Reference Schofield, Thygesen, Das-Munshi, Becares, Cantor-Graae and Agerbo51,Reference Menezes, Georgiades and Boyle53,Reference O'Donoghue, Yung, Wood, Thompson, Lin and McGorry54 Of these, most were cross-sectional but six (four data-sets) were longitudinal.Reference Das-Munshi, Schofield, Bhavsar, Chang, Dewey and Morgan33,Reference Zammit, Lewis, Rasbash, Dalman, Gustafsson and Allebeck47–Reference Schofield, Thygesen, Das-Munshi, Becares, Cantor-Graae and Agerbo51 All these studies were conducted in a neighbourhood context except one, which used a school setting.Reference Zammit, Lewis, Rasbash, Dalman, Gustafsson and Allebeck47 The other six studies examined virtual reality (VR) environments,Reference Veling, Brinkman, Dorrestijn and Van Der Gaag43,Reference Veling, Pot-Kolder, Counotte, van Os and van der Gaag44 perceived ethnic density,Reference Anglin, Lui, Schneider and Ellman52 symptomatology,Reference Eilbracht, Stevens, Wigman, van Dorsselaer and Vollebergh37,Reference Stouten, Veling, Laan and Van der Gaag38 remission,Reference Stouten, Veling, Laan and Van der Gaag38 and ‘bully climate’.Reference Horrevorts, Monshouwer, Wigman and Vollebergh45

Around half of the studies (n = 15, 47%) examined first incident casesReference Boydell, Van Os, McKenzie, Allardyce, Goel and McCreadie9,Reference Kirkbride, Boydell, Ploubidis, Morgan, Dazzan and McKenzie26–Reference Schofield, Ashworth and Jones29,Reference Bhavsar, Boydell, Murray and Power32,Reference Kirkbride, Morgan, Fearon, Dazzan, Murray and Jones36,Reference Termorshuizen, Smeets, Braam and Veling39,Reference van Os, Driessen, Gunther and Delespaul41,Reference Veling, Susser, van Os, Mackenbach, Selten and Hoek42,Reference Mezuk, Li, Cederin, Concha, Kendler and Sundquist46–Reference Dykxhoorn, Lewis, Hollander, Kirkbride and Dalman48,Reference Schofield, Thygesen, Das-Munshi, Becares, Cantor-Graae and Pedersen50,Reference Schofield, Thygesen, Das-Munshi, Becares, Cantor-Graae and Agerbo51 and seven (22%) used measures of subclinical psychosis.Reference Das-Munshi, Bécares, Boydell, Dewey, Morgan and Stansfeld11,Reference Schofield, Das-Munshi, Bécares, Morgan, Bhavsar and Hotopf18,Reference Bécares, Nazroo and Stafford30,Reference Bécares and Das-Munshi31,Reference Halpern and Nazroo34,Reference Horrevorts, Monshouwer, Wigman and Vollebergh45,Reference Anglin, Lui, Schneider and Ellman52 The others assessed symptomatic outcomes,Reference Eilbracht, Stevens, Wigman, van Dorsselaer and Vollebergh37,Reference Stouten, Veling, Laan and Van der Gaag38,Reference Veling, Brinkman, Dorrestijn and Van Der Gaag43,Reference Veling, Pot-Kolder, Counotte, van Os and van der Gaag44 mortality rates,Reference Das-Munshi, Schofield, Bhavsar, Chang, Dewey and Morgan33 length of admission,Reference Heslin, Khondoker, Shetty, Pritchard, Jones and Osborn35 compulsory admission,Reference Terhune, Dykxhoorn, Mackay, Hollander, Kirkbride and Dalman49 individuals meeting ultra-high risk (UHR) criteria,Reference O'Donoghue, Yung, Wood, Thompson, Lin and McGorry54 dispensed antipsychotic medication,Reference Termorshuizen, Heerdink and Selten40 lifetime prevalence of psychosis,Reference Menezes, Georgiades and Boyle53 psychophysiological outcomesReference Veling, Brinkman, Dorrestijn and Van Der Gaag43 and interpersonal distance.Reference Veling, Brinkman, Dorrestijn and Van Der Gaag43,Reference Veling, Pot-Kolder, Counotte, van Os and van der Gaag44 Study characteristics are summarised in Supplementary Table 1.

Summary of results by minority group sample

Combined ethnic minority or migrant groups

Seventeen studies (fifteen data-sets) reported associations for aggregated minority ethnic or migrant groups.Reference Boydell, Van Os, McKenzie, Allardyce, Goel and McCreadie9,Reference Das-Munshi, Bécares, Boydell, Dewey, Morgan and Stansfeld11,Reference Kirkbride, Boydell, Ploubidis, Morgan, Dazzan and McKenzie26,Reference Richardson, Hameed, Perez, Jones and Kirkbride28,Reference Bécares, Nazroo and Stafford30,Reference Das-Munshi, Schofield, Bhavsar, Chang, Dewey and Morgan33–Reference Kirkbride, Morgan, Fearon, Dazzan, Murray and Jones36,Reference Termorshuizen, Smeets, Braam and Veling39,Reference Veling, Susser, van Os, Mackenbach, Selten and Hoek42,Reference Mezuk, Li, Cederin, Concha, Kendler and Sundquist46–Reference Terhune, Dykxhoorn, Mackay, Hollander, Kirkbride and Dalman49,Reference Menezes, Georgiades and Boyle53,Reference O'Donoghue, Yung, Wood, Thompson, Lin and McGorry54 In combined minority groups in the UKReference Boydell, Van Os, McKenzie, Allardyce, Goel and McCreadie9,Reference Das-Munshi, Bécares, Boydell, Dewey, Morgan and Stansfeld11,Reference Kirkbride, Boydell, Ploubidis, Morgan, Dazzan and McKenzie26,Reference Richardson, Hameed, Perez, Jones and Kirkbride28,Reference Bécares, Nazroo and Stafford30,Reference Halpern and Nazroo34,Reference Kirkbride, Morgan, Fearon, Dazzan, Murray and Jones36 and migrant groups in Sweden,Reference Mezuk, Li, Cederin, Concha, Kendler and Sundquist46–Reference Dykxhoorn, Lewis, Hollander, Kirkbride and Dalman48 The NetherlandsReference Termorshuizen, Smeets, Braam and Veling39,Reference Veling, Susser, van Os, Mackenbach, Selten and Hoek42 and Canada,Reference Menezes, Georgiades and Boyle53 all but one studyReference Mezuk, Li, Cederin, Concha, Kendler and Sundquist46 found associations in the expected direction for clinicalReference Boydell, Van Os, McKenzie, Allardyce, Goel and McCreadie9,Reference Kirkbride, Boydell, Ploubidis, Morgan, Dazzan and McKenzie26,Reference Richardson, Hameed, Perez, Jones and Kirkbride28,Reference Kirkbride, Morgan, Fearon, Dazzan, Murray and Jones36,Reference Termorshuizen, Smeets, Braam and Veling39,Reference Veling, Susser, van Os, Mackenbach, Selten and Hoek42,Reference Zammit, Lewis, Rasbash, Dalman, Gustafsson and Allebeck47,Reference Dykxhoorn, Lewis, Hollander, Kirkbride and Dalman48,Reference Menezes, Georgiades and Boyle53 and non-clinical outcomes,Reference Das-Munshi, Bécares, Boydell, Dewey, Morgan and Stansfeld11,Reference Bécares, Nazroo and Stafford30,Reference Halpern and Nazroo34 with many finding significant relationships.Reference Boydell, Van Os, McKenzie, Allardyce, Goel and McCreadie9,Reference Das-Munshi, Bécares, Boydell, Dewey, Morgan and Stansfeld11,Reference Halpern and Nazroo34,Reference Termorshuizen, Smeets, Braam and Veling39,Reference Veling, Susser, van Os, Mackenbach, Selten and Hoek42,Reference Zammit, Lewis, Rasbash, Dalman, Gustafsson and Allebeck47,Reference Dykxhoorn, Lewis, Hollander, Kirkbride and Dalman48 (Another study in The NetherlandsReference Veling, Hoek and Mackenbach55 examined the relationship between group density and perceived discrimination in a migrant sample of individuals with psychosis and controls.) Between-group density effects tended to be stronger than within-group effectsReference Kirkbride, Morgan, Fearon, Dazzan, Murray and Jones36,Reference Termorshuizen, Smeets, Braam and Veling39 and one study found a significant association for affective but not non-affective psychosis.Reference Richardson, Hameed, Perez, Jones and Kirkbride28 For other outcomes, significant associations were observed for mortality ratesReference Das-Munshi, Schofield, Bhavsar, Chang, Dewey and Morgan33 and compulsory admission,Reference Terhune, Dykxhoorn, Mackay, Hollander, Kirkbride and Dalman49 but not for duration of admissionReference Heslin, Khondoker, Shetty, Pritchard, Jones and Osborn35 or meeting UHR criteria.Reference O'Donoghue, Yung, Wood, Thompson, Lin and McGorry54

Black populations

Fourteen studies (twelve data-sets) included Black individuals.Reference Das-Munshi, Bécares, Boydell, Dewey, Morgan and Stansfeld11,Reference Schofield, Das-Munshi, Bécares, Morgan, Bhavsar and Hotopf18,Reference Kirkbride, Jones, Ullrich and Coid27,Reference Schofield, Ashworth and Jones29–Reference Halpern and Nazroo34,Reference Termorshuizen, Smeets, Braam and Veling39,Reference Termorshuizen, Heerdink and Selten40,Reference Dykxhoorn, Lewis, Hollander, Kirkbride and Dalman48,Reference Schofield, Thygesen, Das-Munshi, Becares, Cantor-Graae and Pedersen50,Reference Schofield, Thygesen, Das-Munshi, Becares, Cantor-Graae and Agerbo51 Significant group density associations were found in aggregated Black clinical and non-clinical samples in the UK.Reference Schofield, Das-Munshi, Bécares, Morgan, Bhavsar and Hotopf18,Reference Schofield, Ashworth and Jones29 In Black Caribbean populations,Reference Das-Munshi, Bécares, Boydell, Dewey, Morgan and Stansfeld11,Reference Schofield, Das-Munshi, Bécares, Morgan, Bhavsar and Hotopf18,Reference Kirkbride, Jones, Ullrich and Coid27,Reference Bécares, Nazroo and Stafford30–Reference Halpern and Nazroo34 significant results were observed for subclinical psychosisReference Schofield, Das-Munshi, Bécares, Morgan, Bhavsar and Hotopf18,Reference Halpern and Nazroo34 and schizophrenia first incident casesReference Bhavsar, Boydell, Murray and Power32 in the UK, and strong associations were consistently observed in Antillean individuals for non-affective psychosisReference Termorshuizen, Smeets, Braam and Veling39 and prescribed antipsychoticsReference Termorshuizen, Heerdink and Selten40 in The Netherlands. Other UK studies reported weaker or no evidence of associations in Caribbean groups for subclinical psychosis,Reference Das-Munshi, Bécares, Boydell, Dewey, Morgan and Stansfeld11,Reference Bécares, Nazroo and Stafford30,Reference Bécares and Das-Munshi31 non-affective psychosisReference Kirkbride, Jones, Ullrich and Coid27 and mortality rates.Reference Das-Munshi, Schofield, Bhavsar, Chang, Dewey and Morgan33 In Black African individuals,Reference Schofield, Das-Munshi, Bécares, Morgan, Bhavsar and Hotopf18,Reference Kirkbride, Jones, Ullrich and Coid27,Reference Bhavsar, Boydell, Murray and Power32,Reference Das-Munshi, Schofield, Bhavsar, Chang, Dewey and Morgan33,Reference Terhune, Dykxhoorn, Mackay, Hollander, Kirkbride and Dalman49–Reference Schofield, Thygesen, Das-Munshi, Becares, Cantor-Graae and Agerbo51 a strong association between ethnic density during adolescence and later psychosis was observed in DenmarkReference Schofield, Thygesen, Das-Munshi, Becares, Cantor-Graae and Pedersen50,Reference Schofield, Thygesen, Das-Munshi, Becares, Cantor-Graae and Agerbo51 and Sweden,Reference Dykxhoorn, Lewis, Hollander, Kirkbride and Dalman48 with one study finding stronger associations in second-generationReference Schofield, Thygesen, Das-Munshi, Becares, Cantor-Graae and Agerbo51 and the other in first-generation African migrants.Reference Dykxhoorn, Lewis, Hollander, Kirkbride and Dalman48 In the UK, a significant relationship was found for Black African individuals and non-affective psychosis.Reference Kirkbride, Jones, Ullrich and Coid27 Other UK studies found no significant associations in Black African groups,Reference Schofield, Das-Munshi, Bécares, Morgan, Bhavsar and Hotopf18,Reference Bhavsar, Boydell, Murray and Power32,Reference Das-Munshi, Schofield, Bhavsar, Chang, Dewey and Morgan33 although one found weak evidence of an association for all-cause mortality (P = 0.068).Reference Das-Munshi, Schofield, Bhavsar, Chang, Dewey and Morgan33

Asian populations

Eight studies (seven data-sets) examined Asian populations.Reference Das-Munshi, Bécares, Boydell, Dewey, Morgan and Stansfeld11,Reference Kirkbride, Jones, Ullrich and Coid27,Reference Bécares, Nazroo and Stafford30,Reference Bécares and Das-Munshi31,Reference Das-Munshi, Schofield, Bhavsar, Chang, Dewey and Morgan33,Reference Halpern and Nazroo34,Reference Dykxhoorn, Lewis, Hollander, Kirkbride and Dalman48,Reference Schofield, Thygesen, Das-Munshi, Becares, Cantor-Graae and Pedersen50 In combined Asian groups, consistent associations between own-group density and non-affective psychosis were observed in DenmarkReference Schofield, Thygesen, Das-Munshi, Becares, Cantor-Graae and Pedersen50 and Sweden,Reference Dykxhoorn, Lewis, Hollander, Kirkbride and Dalman48 with the latter demonstrating a stronger relationship in first-generation Asian migrants.Reference Dykxhoorn, Lewis, Hollander, Kirkbride and Dalman48 There was also a strong association with all-cause mortality rates in the UK.Reference Das-Munshi, Schofield, Bhavsar, Chang, Dewey and Morgan33 When considering Asian subgroups, UK studiesReference Das-Munshi, Bécares, Boydell, Dewey, Morgan and Stansfeld11,Reference Kirkbride, Jones, Ullrich and Coid27,Reference Bécares, Nazroo and Stafford30,Reference Bécares and Das-Munshi31,Reference Halpern and Nazroo34 found associations in the expected direction in Indian and Bangladeshi groups for subclinical psychosis,Reference Das-Munshi, Bécares, Boydell, Dewey, Morgan and Stansfeld11,Reference Bécares, Nazroo and Stafford30,Reference Bécares and Das-Munshi31,Reference Halpern and Nazroo34 although one study examining first incident psychosis cases reported no evidence of a relationship in Bangladeshi individuals.Reference Kirkbride, Jones, Ullrich and Coid27 Only one study included African Asian and Chinese samples,Reference Halpern and Nazroo34 no significant correlations were found for either group. In Pakistani individuals, no study found evidence of an association,Reference Das-Munshi, Bécares, Boydell, Dewey, Morgan and Stansfeld11,Reference Bécares, Nazroo and Stafford30,Reference Bécares and Das-Munshi31,Reference Halpern and Nazroo34 with two studies noting detrimental relationships.Reference Bécares, Nazroo and Stafford30,Reference Halpern and Nazroo34

White Other populations

Seven studies (five data-sets) reported results for White Other samples.Reference Das-Munshi, Bécares, Boydell, Dewey, Morgan and Stansfeld11,Reference Kirkbride, Jones, Ullrich and Coid27,Reference Bécares and Das-Munshi31,Reference Das-Munshi, Schofield, Bhavsar, Chang, Dewey and Morgan33,Reference Dykxhoorn, Lewis, Hollander, Kirkbride and Dalman48,Reference Schofield, Thygesen, Das-Munshi, Becares, Cantor-Graae and Pedersen50,Reference Schofield, Thygesen, Das-Munshi, Becares, Cantor-Graae and Agerbo51 In the UK, associations were in the expected direction but non-significant in Irish individuals for subclinical psychosis,Reference Das-Munshi, Bécares, Boydell, Dewey, Morgan and Stansfeld11,Reference Bécares and Das-Munshi31 and no evidence for a relationship was observed in Irish individuals for mortality ratesReference Das-Munshi, Schofield, Bhavsar, Chang, Dewey and Morgan33 or in a non-British White sample for non-affective psychosis.Reference Kirkbride, Jones, Ullrich and Coid27 There was also no association in non-Swedish Nordic or non-Nordic European migrants in Sweden.Reference Dykxhoorn, Lewis, Hollander, Kirkbride and Dalman48 However, in Denmark, significant relationships were found in non-Scandinavian European groups for non-affective psychosis,Reference Schofield, Thygesen, Das-Munshi, Becares, Cantor-Graae and Pedersen50 with negligible differences between first- and second-generation migrants.Reference Schofield, Thygesen, Das-Munshi, Becares, Cantor-Graae and Agerbo51

Other ethnic groups

Seven studies (six data-sets) included other ethnic minority and migrant groups.Reference Termorshuizen, Smeets, Braam and Veling39,Reference Termorshuizen, Heerdink and Selten40,Reference Veling, Susser, van Os, Mackenbach, Selten and Hoek42,Reference Mezuk, Li, Cederin, Concha, Kendler and Sundquist46,Reference Dykxhoorn, Lewis, Hollander, Kirkbride and Dalman48,Reference Schofield, Thygesen, Das-Munshi, Becares, Cantor-Graae and Pedersen50,Reference Schofield, Thygesen, Das-Munshi, Becares, Cantor-Graae and Agerbo51 Longitudinal analyses in Denmark found significant relationships in Middle Eastern individuals for non-affective psychosis,Reference Schofield, Thygesen, Das-Munshi, Becares, Cantor-Graae and Pedersen50 with stronger associations for second-generation migrants.Reference Schofield, Thygesen, Das-Munshi, Becares, Cantor-Graae and Agerbo51 However, in a Middle Eastern and North African sample in Sweden, there was no significant relationship between own-group density at age 15 and later risk of psychosis.Reference Dykxhoorn, Lewis, Hollander, Kirkbride and Dalman48 The same study found no associations in North American, South American, Swedish and Mixed migrants, with some groups in fact showing (non-significant) detrimental relationships.Reference Dykxhoorn, Lewis, Hollander, Kirkbride and Dalman48 Another Swedish study found no difference in non-affective psychosis risk between Iraqi migrants living in ethnic enclaves and those in predominantly Swedish areas.Reference Mezuk, Li, Cederin, Concha, Kendler and Sundquist46 In migrant groups in The Netherlands, associations were consistently strong for a combined Surinamese/Antillean group and a Surinamese only sample for both non-affective psychosisReference Termorshuizen, Smeets, Braam and Veling39 and antipsychotic usageReference Termorshuizen, Heerdink and Selten40 respectively. However, results were mixed for Turkish and Moroccan groups.Reference Termorshuizen, Smeets, Braam and Veling39,Reference Termorshuizen, Heerdink and Selten40,Reference Veling, Susser, van Os, Mackenbach, Selten and Hoek42

Other social characteristics

Three studies included minority groups classified by characteristics other than ethnicity or migratory background,Reference Schofield, Das-Munshi, Bécares, Morgan, Bhavsar and Hotopf18,Reference van Os, Driessen, Gunther and Delespaul41,Reference Zammit, Lewis, Rasbash, Dalman, Gustafsson and Allebeck47 namely single marital/household status,Reference Schofield, Das-Munshi, Bécares, Morgan, Bhavsar and Hotopf18,Reference van Os, Driessen, Gunther and Delespaul41 disadvantaged social class,Reference Schofield, Das-Munshi, Bécares, Morgan, Bhavsar and Hotopf18,Reference Zammit, Lewis, Rasbash, Dalman, Gustafsson and Allebeck47 social fragmentationReference Zammit, Lewis, Rasbash, Dalman, Gustafsson and Allebeck47 and low academic grades.Reference Zammit, Lewis, Rasbash, Dalman, Gustafsson and Allebeck47 Significantly increased risk of schizophrenia was observed in single individuals living in neighbourhoods with fewer single people in The Netherlands.Reference van Os, Driessen, Gunther and Delespaul41 This was also observed in individuals in single households in a later UK study, but the relationship was non-significant.Reference Schofield, Das-Munshi, Bécares, Morgan, Bhavsar and Hotopf18 A longitudinal study in Sweden assessing associations between school-level own-group density and clinical psychosis found a significant association in socially fragmented groups, but not in those with low grades or deprived status, although the latter approached significance (P = 0.057).Reference Zammit, Lewis, Rasbash, Dalman, Gustafsson and Allebeck47 A relationship for disadvantaged status was not found in the UK neighbourhood-level study, which showed a (non-significant) reverse association.Reference Schofield, Das-Munshi, Bécares, Morgan, Bhavsar and Hotopf18

Virtual reality, symptomatology, perceived ethnic density and bully climate

Six studies used different methods: two used VR,Reference Veling, Brinkman, Dorrestijn and Van Der Gaag43,Reference Veling, Pot-Kolder, Counotte, van Os and van der Gaag44 two looked at symptom profilesReference Eilbracht, Stevens, Wigman, van Dorsselaer and Vollebergh37,Reference Stouten, Veling, Laan and Van der Gaag38 and remission,Reference Stouten, Veling, Laan and Van der Gaag38 one examined perceived ethnic densityReference Anglin, Lui, Schneider and Ellman52 and one considered ‘bully climate’.Reference Horrevorts, Monshouwer, Wigman and Vollebergh45 VR studies simulated high and low group density environments by manipulating the ethnicity of avatars.Reference Veling, Brinkman, Dorrestijn and Van Der Gaag43,Reference Veling, Pot-Kolder, Counotte, van Os and van der Gaag44 Compared with control participants, individuals with psychosis had higher galvanic skin responses in low own-group density conditions.Reference Veling, Brinkman, Dorrestijn and Van Der Gaag43 The second study found no effect of virtual group density on distress or paranoid thoughts.Reference Veling, Pot-Kolder, Counotte, van Os and van der Gaag44 (Veling and colleagues used the VR experimentReference Veling, Pot-Kolder, Counotte, van Os and van der Gaag44 also to examine the effect of virtual social stressors (including minority status) on individuals with differing psychosis liability using additional outcomes such as autonomic balance,Reference Counotte, Pot-Kolder, van Roon, Hoskam, van der Gaag and Veling56 Th17/T regulator cell balance and natural killer cell numbersReference Counotte, Drexhage, Wijkhuijs, Pot-Kolder, Bergink and Hoek57 and interpersonal distance.Reference Geraets, van Beilen, Pot-Kolder, Counotte, van der Gaag and Veling58 Moderators including cognitive biasesReference Pot-Kolder, Veling, Counotte and Van Der Gaag59, self-esteemReference Jongeneel, Pot-Kolder, Counotte, van der Gaag and Veling60 and childhood traumaReference Veling, Counotte, Pot-Kolder, Van Os and Van Der Gaag61 have also been investigated.)

In symptom studies, an ethnic density interaction for paranoia was observed in ethnic majority, but not ethnic minority, adolescents in a Dutch classroom setting,Reference Eilbracht, Stevens, Wigman, van Dorsselaer and Vollebergh37 whereas another study found no association between group density and symptomatic outcomes.Reference Stouten, Veling, Laan and Van der Gaag38

The perceived ethnic density study found that Black, Latino and Asian individuals in the USA who reported growing up in neighbourhoods with higher proportions of out-group ethnic minority individuals reported more psychotic-like symptoms than those who grew up in ethnically concordant or predominantly White neighbourhoods.Reference Anglin, Lui, Schneider and Ellman52 Further, Black individuals who perceived a change in the ethnic density of their neighbourhood during childhood reported more psychotic experiences than those who did not.Reference Anglin, Lui, Schneider and Ellman52

The remaining study examined a group density association for bullying in a classroom setting. Individuals who both bullied others and were victims of bullying reported the highest subclinical psychotic experiences compared with bullies, victims and children not involved in bullying. The association between bully-victim status and psychosis was attenuated by a higher ‘bully climate’, i.e. classrooms with higher proportions of other children involved in bullying in some capacity.Reference Horrevorts, Monshouwer, Wigman and Vollebergh45

Meta-analysis

Ten studies were eligible for meta-analysis.Reference Das-Munshi, Bécares, Boydell, Dewey, Morgan and Stansfeld11,Reference Schofield, Das-Munshi, Bécares, Morgan, Bhavsar and Hotopf18,Reference Richardson, Hameed, Perez, Jones and Kirkbride28–Reference Bécares, Nazroo and Stafford30,Reference Termorshuizen, Heerdink and Selten40,Reference Zammit, Lewis, Rasbash, Dalman, Gustafsson and Allebeck47,Reference Dykxhoorn, Lewis, Hollander, Kirkbride and Dalman48,Reference Schofield, Thygesen, Das-Munshi, Becares, Cantor-Graae and Pedersen50,Reference Menezes, Georgiades and Boyle53 Of the twenty-two studies excluded, six studiesReference Kirkbride, Boydell, Ploubidis, Morgan, Dazzan and McKenzie26,Reference Bécares and Das-Munshi31,Reference Bhavsar, Boydell, Murray and Power32,Reference Kirkbride, Morgan, Fearon, Dazzan, Murray and Jones36,Reference Termorshuizen, Smeets, Braam and Veling39,Reference Schofield, Thygesen, Das-Munshi, Becares, Cantor-Graae and Agerbo51 used overlapping or potentially overlapping data-sets,Reference Das-Munshi, Bécares, Boydell, Dewey, Morgan and Stansfeld11,Reference Schofield, Ashworth and Jones29,Reference Termorshuizen, Heerdink and Selten40,Reference Schofield, Thygesen, Das-Munshi, Becares, Cantor-Graae and Pedersen50 five used non-eligible outcomes,Reference Das-Munshi, Schofield, Bhavsar, Chang, Dewey and Morgan33,Reference Heslin, Khondoker, Shetty, Pritchard, Jones and Osborn35,Reference Eilbracht, Stevens, Wigman, van Dorsselaer and Vollebergh37,Reference Stouten, Veling, Laan and Van der Gaag38,Reference Terhune, Dykxhoorn, Mackay, Hollander, Kirkbride and Dalman49 four used non-eligible exposures (VR simulation,Reference Veling, Brinkman, Dorrestijn and Van Der Gaag43,Reference Veling, Pot-Kolder, Counotte, van Os and van der Gaag44 perceived ethnic densityReference Anglin, Lui, Schneider and Ellman52 and ethnic enclavesReference Mezuk, Li, Cederin, Concha, Kendler and Sundquist46). Four did not adjust for the specified individual and area-level confounds,Reference Kirkbride, Jones, Ullrich and Coid27,Reference van Os, Driessen, Gunther and Delespaul41,Reference Horrevorts, Monshouwer, Wigman and Vollebergh45,Reference O'Donoghue, Yung, Wood, Thompson, Lin and McGorry54 two only examined between-group density effectsReference Boydell, Van Os, McKenzie, Allardyce, Goel and McCreadie9,Reference Veling, Susser, van Os, Mackenbach, Selten and Hoek42 and one did not use multilevel modelling.Reference Halpern and Nazroo34

Although Schofield and colleaguesReference Schofield, Thygesen, Das-Munshi, Becares, Cantor-Graae and Agerbo51 were the first to examine generational differences in the group density effect, their study used the same cohort as another studyReference Schofield, Thygesen, Das-Munshi, Becares, Cantor-Graae and Pedersen50 and, as per the eligibility criteria, we included their earlier study as it included an additional minority group sample (Asian).Reference Schofield, Thygesen, Das-Munshi, Becares, Cantor-Graae and Pedersen50 This meant that Dykxhoorn et alReference Dykxhoorn, Lewis, Hollander, Kirkbride and Dalman48 was the only included paper that stratified results by generational status, so only data for first-generation migrants were extracted from this study.

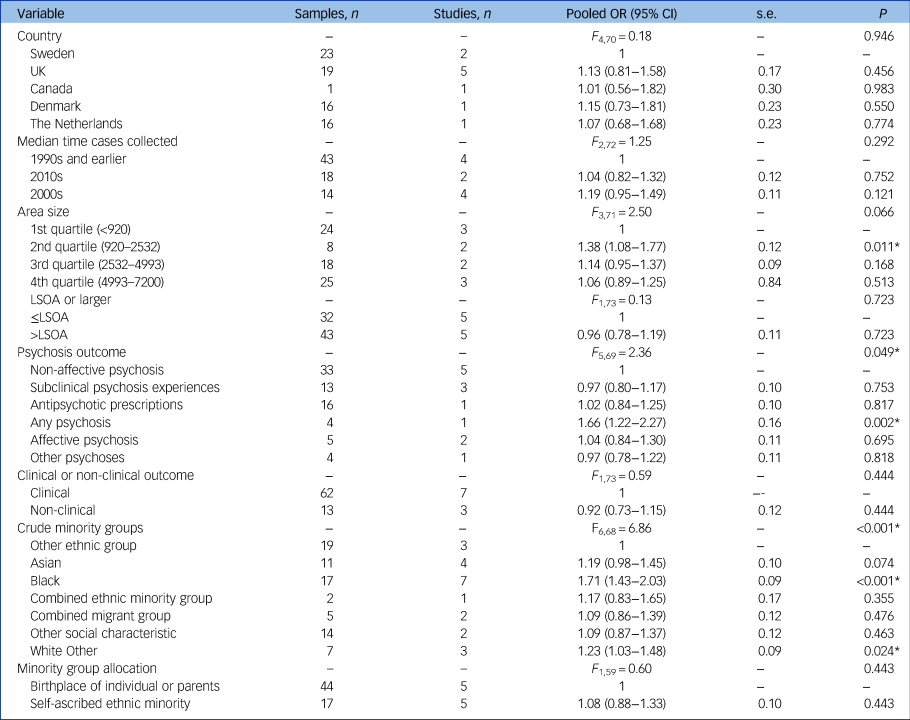

Pooled group density effects

The three-level model was the best fit for the data (Supplemental 8). The overall meta-analytic effect indicated that a 10 percentage-point decrease in group density was associated with a 20% increase in psychosis risk (OR = 1.20, 95% CI 1.09−1.32, P < 0.001). An estimate using only minority groups defined by ethnicity or migratory background was also significant (OR = 1.23, 95% CI 1.14−1.33, P < 0.001). There was no significant effect in minority groups defined by other characteristics (OR = 1.02, 95% CI 0.86−1.20, P = 0.848). Results were similar after removal of the one school-based studyReference Zammit, Lewis, Rasbash, Dalman, Gustafsson and Allebeck47 (OR = 1.25, 95% CI 1.15−1.36, P < 0.001).

Moderator tests

In line with the narrative review, there were moderating effects of crude (F 6,68 = 6.86, P < 0.001) and specific minority groups (F 25,49 = 7.26, P < 0.001). Said moderator tests were also significant when conducted on ethnic minority and migrant samples only (Supplemental 9). Further analyses examining whether associations differed when minority groups were self-ascribed or defined by birthplace were non-significant (F 1,59 = 0.60, P = 0.443).

When assessing crude minority groups, the strongest association was observed in the Black group (OR = 1.71, 95% CI 1.43−2.03, P < 0.001) relative to the reference group (‘Other ethnic group’). There was also a stronger association in the White Other group (OR = 1.23, 95% CI 1.03−1.48, P = 0.024). There was weak evidence of a stronger association in Asian populations (OR = 1.19, 95% CI 0.98−1.45, P = 0.074).

Moderator tests for specific minority groups showed the strongest associations in Black Antillean migrants in The Netherlands (OR = 3.60, 95% CI 2.22−5.83, P < 0.001) relative to the reference group (‘Combined migrant group’). This was followed by Black or Black British (OR = 1.84, 95% CI 1.24−2.74, P = 0.003) and Black African (OR = 1.48, 95% CI 1.10−2.00, P = 0.011) groups in the UK and Denmark. There was also a stronger association in the non-Scandinavian European group (OR = 1.43, 95% CI 1.06−1.92, P = 0.020) and a significant reversed association in a South American sample (OR = 0.37, 95% CI 0.14−0.99, P = 0.048). Table 1 shows moderator test results including crude minority groups, and Supplemental 10 shows specific minority group results.

Table 1 Moderator tests

LSOA, lower super output area.

* P < 0.05.

Moderator tests for country, time and area size were non-significant, although there was some evidence for stronger group density associations at smaller geographic units. There was also a significant moderating effect of psychosis outcome used (F 5,69 = 2.36, P = 0.049), with evidence for stronger associations in studies using clinical outcomes, namely non-affective psychosis cases (OR = 1.15, 95% CI 1.04−1.28, P = 0.008) and cases with a first diagnosis of any psychotic disorder (OR = 1.66, 95% CI 1.22−2.27, P = 0.002).

Sensitivity analyses

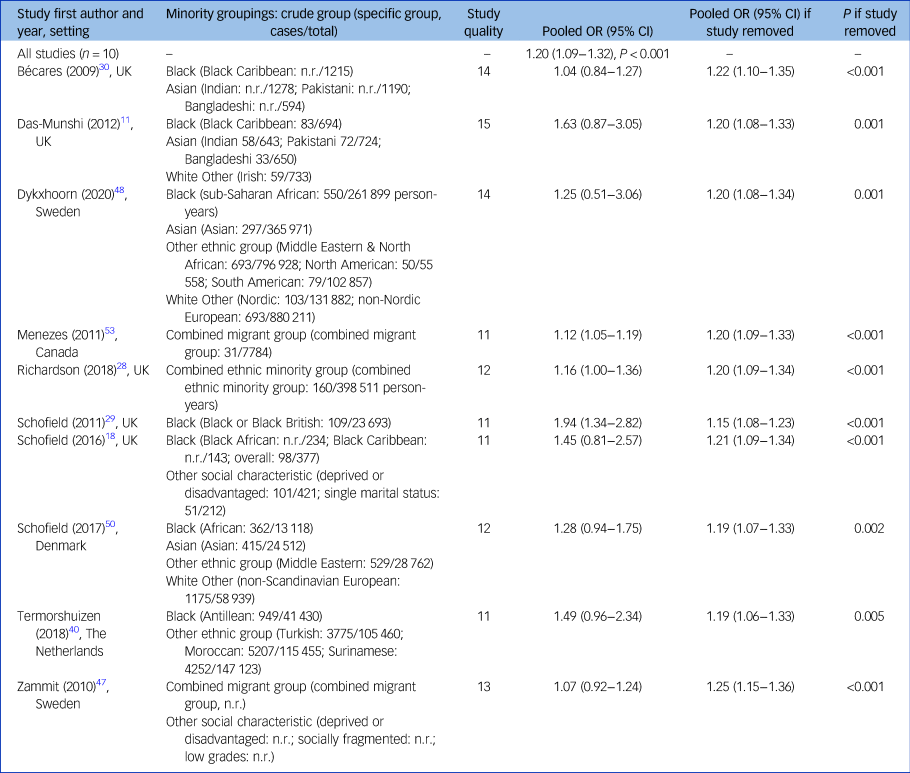

Leave-one-out analysis indicated that removing each study produced negligible changes to the overall pooled effect (Table 2). This was also the case when the 75 effect sizes within the studies were individually removed (Supplemental 11).

Table 2 Effect sizes by study and leave-one-out analysis

n.r., not recorded.

Discussion

Summary

This is the first review providing quantitative evidence that the risk of psychosis posed by lower own-group density areas varies across minority groups. Overall, a 10 percentage-point decrease in own-group density was associated with a 20% increase in risk of psychosis, but this effect was strongly moderated by minority group.

Comparisons with previous reviews

Our overall pooled effect size estimate was similar in magnitude to a previous within-groups meta-analysisReference Bécares, Dewey and Das-Munshi16 but weaker than one examining between-group effects.Reference Bosqui, Hoy and Shannon10 However, contrary to previous analyses,Reference Bécares, Dewey and Das-Munshi16 we observed a strong moderating effect of minority group, particularly when more fine-grained classifications were tested.

In line with previous narrative reviews,Reference Bosqui, Hoy and Shannon10,Reference Shaw, Atkin, Bécares, Albor, Stafford and Kiernan17 we observed the strongest group density associations in Black individuals. A significantly stronger association was also found in the White Other group, driven by strong associations in non-Scandinavian European individuals in Denmark.Reference Schofield, Thygesen, Das-Munshi, Becares, Cantor-Graae and Pedersen50 A reverse relationship was noted in South American migrants to Sweden.Reference Dykxhoorn, Lewis, Hollander, Kirkbride and Dalman48 Such heterogeneity in effect sizes may reflect distinctive social experiences of specific minority groups.Reference Anglin8,Reference Das-Munshi, Bécares, Boydell, Dewey, Morgan and Stansfeld11

Strengths and limitations

A strength of this review is our use of a multilevel meta-analytic model. In the group density literature, it is common to examine multiple groups and so accounting for nesting by study is vital. Another strength is that we used relatively specific minority groupings. It is common practice for group density studies to amalgamate minority samples (e.g. Black and minority ethnic groups), for reasons of statistical power.Reference Schofield, Das-Munshi, Bécares, Morgan, Bhavsar and Hotopf18 As we show, aggregating groups may conceal considerable heterogeneity in risk. This likely reflects distinct social experiences of different minority groups, in turn providing clues to likely mechanisms. For example, the narrative review and meta-analysis indicate that reduced ethnic density confers greater risk to Black populations compared with other groups. However, within the Black group, associations appear stronger in Black Caribbean individuals in The Netherlands than in the UK, highlighting the importance of the varied experiences of different migrant groups.Reference Das-Munshi, Bécares, Boydell, Dewey, Morgan and Stansfeld11

We also acknowledge some limitations. First, regarding ethnic categories, although we attempted to use the same categories as the original studies, our moderator analyses required some judgements about how to combine groups. We sought to be as non-arbitrary as possible by using UK census classifications and author definitions, but clearly no scheme is definitive. This question of how to categorise groups on the meta-analytic level also applies on the study level. The authors of original studies will have had to make these decisions too and may have used a variety of criteria to do so – UK studies tended to use self-ascribed ethnicity, whereas studies in other countries classified groups by birthplace. Further, composition of apparently uniform groups differs by country, e.g. the ethnic subgroups that comprise ‘Asian’ samples. As well as these conceptual issues, when stratifying data into specific groups, there is a trade-off between aggregating and splitting groups in terms of statistical power and error control. These issues, stemming from race's social construction,Reference Sen and Wasow62 make synthesising studies inescapably complicated.

In terms of exposure, rather than exclude studies that quantified group density differently, we attempted to rescale effects so that they all reflected a 10 percentage-point decrease. This allowed us to synthesise more evidence than previous reviews, but it may have resulted in imprecision and extrapolation. Additionally, the quantification of group density by geographical unit is subject to the modifiable areal unit problem.Reference Arcaya, Tucker-Seeley, Kim, Schnake-Mahl, So and Subramanian63

Furthermore, studies varied in how they quantified psychosis. Rather than exclude studies based on their psychosis outcome, we decided to use this as an opportunity to examine whether group density associations differ for non-clinical versus clinical outcomes. Formal moderator tests indicated some evidence that associations were stronger for the latter. This should be considered when observing differences between minority groups (also see Supplemental 7).

In terms of the evidence-base, there are broader issues of temporality and consistency, which are key criteria for assessing causation in epidemiological studies.Reference Pickett and Wilkinson64,Reference Gordis65 Most studies were conducted in similar settings and time periods; there is a dearth of research from outside Europe, for example.Reference Anglin8 Consequently, a reduced range of minority groups were included and, given that a disproportionate number of studies in the meta-analysis were conducted in the UK, generalising findings must be approached with caution.

Our review of group density associations in non-ethnic minorities was also limited by the lack of studies including such samples. This is an important priority for future research in terms of elucidating mechanisms.

Finally, most reviewed studies were cross-sectional: potential mechanisms are discussed in the next section, but there is a clear need for further longitudinal studies to identify causal pathways.Reference Saville14

Proposed mechanisms

Racism and discrimination

The attenuated risk and impact of racial harassment experienced by minority groups in higher own-group neighbourhoods has been proposed as a key mechanism underpinning group density relationships.Reference Das-Munshi, Bécares, Boydell, Dewey, Morgan and Stansfeld11,Reference Bécares, Nazroo and Stafford30,Reference Bécares and Das-Munshi31 Evidence from Europe and the USA suggests that visible minorities,Reference Dykxhoorn, Lewis, Hollander, Kirkbride and Dalman48 particularly Black individuals, are at especially high risk of experiencing discrimination and coercive pathways to psychiatric treatment.Reference Morgan, Knowles and Hutchinson7,Reference Das-Munshi, Bécares, Boydell, Dewey, Morgan and Stansfeld11,Reference McKenzie66,Reference Oh, Cogburn, Anglin, Lukens and DeVylder67 Evidence suggests that minorities living in lower own-group density areas also anticipate more discrimination from healthcare services.Reference Bécares and Das-Munshi31 Combined with findings that ethnic minorities experience greater mental health-related stigma,Reference Clement, Schauman, Graham, Maggioni, Evans-Lacko and Bezborodovs68 this may exacerbate delays in help-seekingReference Memon, Taylor, Mohebati, Sundin, Cooper and Scanlon69 and has important implications for early intervention services.

Some evidence indicates that changes to neighbourhood ethnic composition can drive anti-immigration sentiment, especially in areas that have experienced rapid rates of change,Reference Inglehart and Norris70–Reference Goodwin and Milazzo72 but this has not been examined in the context of group density associations. The perceived loss of power associated with the prospect of becoming a minority has been suggested to drive majority group individuals’ exclusionary and hostile treatment of minorities.Reference Eilbracht, Stevens, Wigman, van Dorsselaer and Vollebergh37,Reference Outten, Schmitt, Miller and Garcia73 Consequently, some minority groups may in fact be at elevated risk of psychosis in newly high ethnic density areas. This may explain detrimental own-group density relationships observed in some populations.Reference Bécares, Nazroo and Stafford30,Reference Halpern and Nazroo34,Reference Dykxhoorn, Lewis, Hollander, Kirkbride and Dalman48 It is also important to contextualise studies in terms of their socio-political context, e.g. there has been a stark increase in anti-Asian discrimination during the COVID-19 pandemic.Reference Chen, Zhang and Liu74 This may be an important influence in post-COVID-19 group density studies including Asian populations.

Deprivation

In addition to overt discrimination, disproportionate poverty or the propensity to ‘drift’ into more deprived areas were thought to be key drivers of the excess psychosis risk in ethnic minorities.Reference Dykxhoorn and Kirkbride6,Reference Barnard and Turner75,Reference Read, Johnstone, Taitimu, Read and Dillon76 However, ethnic density associations tend to persist after adjustment for deprivation.Reference Bosqui, Hoy and Shannon10,Reference Bécares, Dewey and Das-Munshi16 Furthermore, given that areas with higher density of ethnic minorities are often more deprived,Reference Heslin, Khondoker, Shetty, Pritchard, Jones and Osborn35,Reference Heinz, Deserno and Reininghaus77 any residual confounding might be expected to operate in the opposite direction to density effects in minority groups.Reference Bosqui, Hoy and Shannon10,Reference Bécares, Dewey and Das-Munshi16 There is, however, evidence that social drift prior to diagnosis may artifactually produce ethnic density associations in majority groups,Reference Termorshuizen, Smeets, Braam and Veling39 which may explain between-group density effectsReference Bosqui, Hoy and Shannon10 appearing larger than within-group effects.Reference Bécares, Dewey and Das-Munshi16

Social capital

Social capital is thought to have a key role in the protective effects of own-group density.Reference Das-Munshi, Bécares, Boydell, Dewey, Morgan and Stansfeld11,Reference Kirkbride, Morgan, Fearon, Dazzan, Murray and Jones36 It has been defined as ‘connections among individuals – social networks and the norms of reciprocity and trustworthiness that arise from them’.Reference Putnam78 The increased access to social capital garnered by minorities living in high own-group areas is proposed to weaken the impact of social adversity such as discriminationReference Das-Munshi, Bécares, Boydell, Dewey, Morgan and Stansfeld11,Reference Bécares, Nazroo and Stafford30 and deprivation.Reference Handley, Oakley and Saville79 There is evidence that the association between social capital and psychosis risk is non-linear, with neighbourhoods characterised by high and low levels of social capital conferring the highest risk of psychosis.Reference Kirkbride, Boydell, Ploubidis, Morgan, Dazzan and McKenzie26 High social capital, particularly bonding social capital,Reference Putnam78 may increase risk in individuals who experience or perceive exclusion from the networks that it represents,Reference McKenzie, Whitley and Weich80,Reference Saville81 such as ethnic minorities in lower own-group density areas.Reference Kirkbride, Boydell, Ploubidis, Morgan, Dazzan and McKenzie26

Migration and ‘acculturation’

Studies have indicated that the stress of migration and adaptation to the host culture contribute to the excess risk of psychosis in minorities, although this risk may be reduced in those who speak the host language and have higher educational and employment prospects.Reference Selten and Termorshuizen4,Reference Morgan, Knowles and Hutchinson7 Although we did not find moderation by country, there is some evidence to support this notion, with some studies finding lower psychosis prevalence and weaker or absent group density associations in CanadaReference Menezes, Georgiades and Boyle53 and Australia,Reference O'Donoghue, Yung, Wood, Thompson, Lin and McGorry54 countries where immigration policy gives preference to individuals with these characteristics.

Factors related to low ‘acculturation’ (e.g. majority language ability) are more prevalent in first-generation migrants than in their children, who are commonly more ‘assimilated’ into the host culture.Reference Anglin8,Reference Dykxhoorn, Lewis, Hollander, Kirkbride and Dalman48,Reference Veling, Hoek, Wiersma and Mackenbach82 Recent evidence suggests that linguistic factors confer greater risk of psychosis in first-generation migrants, whereas social disadvantageReference Jongsma, Gayer-Anderson, Tarricone, Velthorst, van der Ven and Quattrone83 and the stress of alienation from both identities (marginalisation) or rejecting culture of origin in favour of the host culture (assimilation) are proposed to underpin risk in subsequent generations.Reference Schofield, Thygesen, Das-Munshi, Becares, Cantor-Graae and Agerbo51,Reference Veling, Hoek, Wiersma and Mackenbach82,Reference El Bouhaddani S, van Domburgh, Schaefer, Doreleijers and Veling84 Generational differences in the group density effect could therefore shed light on the processes driving the increased risk. However, to date literature examining this is mixedReference Bécares, Dewey and Das-Munshi16,Reference Dykxhoorn, Lewis, Hollander, Kirkbride and Dalman48,Reference Schofield, Thygesen, Das-Munshi, Becares, Cantor-Graae and Agerbo51 and there were too few studies stratifying by generation to allow for meaningful moderator analysis in the present review.

Pathways to psychosis

Both material and psychological processes likely drive group density associations, and these may not be mutually exclusive. Material processes refer to factors preventing individuals from accessing the resources and capacities required for autonomy,Reference Marmot85,Reference Qureshi86 e.g. individuals who do not speak the majority language may find it harder to find work or access appropriate mental health services in low own-group density areas.Reference Memon, Taylor, Mohebati, Sundin, Cooper and Scanlon69 This also includes deliberate attempts to exclude minority groups and restrict their access to opportunities and support networks.Reference McKenzie66,Reference Qureshi86 This explains why group density effects are observed in marginalised groups, including ethnic minorities,Reference Bosqui, Hoy and Shannon10,Reference Bécares, Dewey and Das-Munshi16,Reference Shaw, Atkin, Bécares, Albor, Stafford and Kiernan17 isolated single people,Reference Schofield, Das-Munshi, Bécares, Morgan, Bhavsar and Hotopf18,Reference van Os, Driessen, Gunther and Delespaul41 people with deprived social statusReference Schofield, Das-Munshi, Bécares, Morgan, Bhavsar and Hotopf18,Reference Zammit, Lewis, Rasbash, Dalman, Gustafsson and Allebeck47 and LGBTQ+ individuals,Reference Hatzenbuehler, Keyes and McLaughlin12 while there is some suggestion that minority groups with a greater share of power do not experience the same degree of risk to their mental health.Reference Selten and Termorshuizen4,Reference Suvisaari, Opler, Lindbohm and Sallmén87 That said, there has been limited investigation into group density associations in these groups. To identify key mechanisms, it would be theoretically useful to examine whether group density is an important social determinant of psychosis in less marginalised minority groups such as Swedish speakers in Finland, who comprise a linguistic minority but generally occupy a higher socioeconomic position and live longer than the Finnish-speaking majority.Reference Suvisaari, Opler, Lindbohm and Sallmén87

Psychological processes relate to the mental consequences of belonging to a disempowered group. There are several theoretical frameworks for conceptualising the psychological sequelae of marginalised minority group membership, including the minority stress model,Reference Meyer88 social defeatReference Selten, Van Der Ven, Rutten and Cantor-Graae89 and social identity theory.Reference Tajfel, Turner, Austin, Worchel, Hatch and Schultz90,Reference McIntyre, Wickham, Barr and Bentall91 These mechanisms may be especially important in the aetiology of psychotic disorders, given that group density effects appear to have a degree of specificity to psychosis.Reference Bécares, Dewey and Das-Munshi16,Reference Shaw, Atkin, Bécares, Albor, Stafford and Kiernan17 Although the evidence is limited, negative evaluations of self and othersReference Fowler, Freeman, Smith, Kuipers, Bebbington and Bashforth92 (exacerbated by experiences of racism) appear to have a unique role in paranoia, but not in hallucinations.Reference McIntyre, Wickham, Barr and Bentall91,Reference Janssen, Hanssen, Bak, Bijl, de Graaf and Vollebergh93 Supporting neurobiological evidence from non-clinical samples indicates that Black individuals in lower own-group density areas perceive greater social threat in response to White faces,Reference McCutcheon, Bloomfield, Dahoun, Quinlan, Terbeck and Mehta94 suggesting a possible pathway to paranoia.Reference McCutcheon, Bloomfield, Dahoun, Quinlan, Terbeck and Mehta94 Conversely, the social deafferentation hypothesis suggests that social isolation has stronger links with hallucinations.Reference Hoffman95 Therefore the former is perhaps a more common pathway in Black individuals and the latter in groups who experience greater linguistic and cultural barriers, e.g. first-generation migrants.Reference Dykxhoorn, Lewis, Hollander, Kirkbride and Dalman48,Reference Anglin, Lui, Schneider and Ellman52,Reference Jongsma, Gayer-Anderson, Tarricone, Velthorst, van der Ven and Quattrone83

These social processes highlight the importance of contextualising psychotic experiences in minority groups and considering to what extent these are understandable responses to chronic experiences of discrimination and social exclusion.Reference Johnstone and Boyle96

Implications

There has been limited discussion of the implications of group density findings, particularly with regard to policy. This is understandable, given that these findings could be viewed as arguments in favour of ethnic segregation. However, residential segregation has instead been associated with poorer health.Reference Maguire, French and O'Reilly97,Reference Pickett and Wilkinson98 Further, it is plausible that the risks associated with low own-group density areas are a manifestation of disempowerment experienced by that group and the effect might therefore be attenuated if minority groups experienced less social disadvantage. To appropriately address these issues, the underpinning individual-level and systemic factors must be examined.Reference Anglin99

It has been argued that focusing on assimilating migrants into host cultures exacerbates the dominant culture's ‘othering’ of minority groups,Reference Simonsen100 creating greater disconnect between their parental and host cultures,Reference Schofield, Thygesen, Das-Munshi, Becares, Cantor-Graae and Agerbo51 which is likely to have unfavourable mental health consequences.Reference Schofield, Thygesen, Das-Munshi, Becares, Cantor-Graae and Agerbo51,Reference Veling, Hoek, Wiersma and Mackenbach82 As an alternative, strategies to create cross-cutting identities may be efficacious in increasing access to bridging social capital, which has a protective effect.Reference McKenzie, Whitley and Weich80,Reference Kunst, Thomsen, Sam and Berry101 Establishing positive intergroup contact may be especially challenging for individuals prone to psychosis, who may be more likely to perceive others as a threat,Reference Reininghaus, Kempton, Valmaggia, Craig, Garety and Onyejiaka102 but facilitating positive contact may help foster stable social identities, in terms of minority groups’ connectedness with both their cultural group and wider community.Reference Schofield, Thygesen, Das-Munshi, Becares, Cantor-Graae and Agerbo51 That said, creating the social conditions to enable minorities to form strong civic identities and access bridging social capital will only be achieved by systemic changes to reduce community-level social inequality and, crucially, the structural racism that sustains inequities in the social, economic and living circumstances of minority groups.Reference Morgan, Knowles and Hutchinson7,Reference Anglin99

As well as these wider systemic issues, useful targets for clinical intervention might include strategies to improve clinicians’ cultural competenceReference Anglin99,Reference Edge, Degnan, Cotterill, Berry, Baker and Drake103 and understanding of the disempowerment experienced by minority groups, and how this may be amplified in low own-group density areas. To better inform interventions, further investigation is needed to determine when in life low-own group density confers the greatest risk.Reference Kirkbride, Morgan, Fearon, Dazzan, Murray and Jones36 Therapeutic approaches that aim to develop strong social identities might also be efficacious.

Future research

The logic of group density designs assumes that individuals living in low and high own-group density areas can be straightforwardly compared.Reference Saville14 Given that the reasons for large minority group populations in particular areas are not arbitrary – rather, they are linked with factors such as family, housing cost and employmentReference Selten and Termorshuizen4 – it is difficult to disentangle the contextual and compositional effectsReference Maxwell104 of own-group density. There is a clear need for longitudinal designsReference Shaw, Atkin, Bécares, Albor, Stafford and Kiernan17 and demonstrations that associations persist across different settings and time periods.Reference Selten and Termorshuizen4

The present review suggests that the group density effect is complex and appears to vary by minority group, with the strongest associations observed in Black populations. To substantiate our findings and elucidate mechanisms, more studies examining specific ethnic minorities are required. Future work should also test for group density associations in minorities defined by other characteristics. In addition to epidemiological studies, proposed avenues for future research should be explored using different methodologies, such as qualitative interviews,Reference Whitley, Princ, McKenzie and Stewart105 experience-based approaches,Reference Söderström, Empson, Codeluppi, Söderström, Baumann and Conus106 neurobiological studiesReference McCutcheon, Bloomfield, Dahoun, Quinlan, Terbeck and Mehta94 and VRReference Veling, Pot-Kolder, Counotte, van Os and van der Gaag44 to better capture the subjective experiences driving group density effects.Reference Anglin8

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2021.96.

Data availability

Data availability is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to the authors who assisted with this work by responding to our queries and/or providing additional data. We are also grateful to Yasmin Noorani for her help with developing and piloting the search strategy and to Karan and Tony Baker for proofreading.

Author contributions

S.J.B. wrote the manuscript; all authors meet the ICMJE criteria for authorship and have approved the final version. Review concept and design: S.J.B. and C.W.N.S.; data acquisition: S.J.B.; statistical analysis: S.J.B. and C.W.N.S.; interpretation: S.J.B., C.W.N.S., M.J. and H.J.; drafting and revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content: S.J.B., C.W.N.S., M.J. and H.J..

Funding

S.J.B. is funded by the Economic Social Research Council (ESRC) Wales Doctoral Training Partnership.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.