Two competing narratives characterize the role of race in Brazil’s 2018 election, in which far-right firebrand Jair Bolsonaro was elected president. In one view, 2018 was yet another example of the country’s paradoxical racial politics: significant shares of black and brown voters were said to support Bolsonaro despite his inflammatory and racist rhetoric targeting Afro-descendants and progressive racial policies like affirmative action (Caleiro Reference Caleiro2018; Calgaro and Caram Reference Calgaro and Caram2017; G1 2017).Footnote 1 For example, Bolsonaro once told black movement protesters to “go back to the zoo,” and has been legally ordered to pay damages for such comments (Pragmatismo 2013; Rouvenat Reference Rouvenat2017). Yet journalists in particular remarked on the surprising levels of support Bolsonaro managed to garner from voters of color (Clarín 2018; Sousa Reference Sousa2018; Spektor Reference Spektor2018). As Faiola and Lopes (Reference Faiola and Lopes2018) put it, Bolsonaro “entranced” voters of color “while insulting them.” In this view, Bolsonaro’s shocking rhetoric did little to set Brazil’s 2018 election apart from prior elections, in which race was deemed irrelevant to electoral preferences or outcomes, even among the ostensible targets of racism.

In contrast, other scholars have argued that the 2018 election was a significant departure from the past. Bolsonaro’s candidacy and his racial rhetoric represented an unprecedented electoral salience of race in Brazilian elections (Avendaño and Gortázar Reference Avendaño and Gortázar2018; Layton et al. Reference Layton, Smith, Moseley and Cohen2021; Silva and Larkins Reference Silva and Larkins2019). Previously, political scientists had argued that few social cleavages or differences found expression in the political arena (Mainwaring Reference Mainwaring1999; Samuels Reference Samuels2006) and that campaign strategies of courting votes along racial lines had led to electoral defeat (Mitchell Reference Mitchell2009; Oliveira Reference Oliveira2007). Bolsonaro’s rhetoric therefore signaled that 2018 was different, and consequently voters had good and inescapable reasons to factor their racial identities into electoral calculations. In 2018, race was relevant to voters in ways it simply was not before.

In this article, I argue that neither perspective fully captures the racial dynamics of Brazil’s 2018—and possibly earlier—elections. I show that racial identification emerged as a significant predictor of presidential support for the leftist Workers’ Party (PT, Partido dos Trabalhadores) long before Bolsonaro’s candidacy, and that the racialized behavior identified in previous analyses of the 2018 election (Almeida and Guarnieri Reference Almeida and Guarnieri2020; Amaral Reference Amaral2020; Layton et al. Reference Layton, Smith, Moseley and Cohen2021) does not depart from this longer-term pattern in direction or degree. The relevant question, I argue, is not if race impacts voter preferences but for whom it does. To better explain racialized and overlooked patterns of voter behavior, this study draws on recent accounts of racial subjectivity in Brazil to argue that racial voting—that is, whether racial identifications impact voter behavior—varies between and within racial categories.

At first glance, we might easily expect voters who are most likely to feel targeted by racist rhetoric—black voters—to be most likely to oppose Bolsonaro. But black voters in Brazil have not historically exhibited the same level of electoral cohesion observed elsewhere. We must therefore modify our expectations of how and when racial groups diverge in their electoral preferences and focus our expectations on the racially conscious—those who choose black identification and have high levels of educational attainment, as recent studies have shown (De Micheli Reference De Micheli2021; Mitchell-Walthour Reference Mitchell-Walthour2018; Telles and Paschel Reference Telles and Paschel2014).

This argument is tested with analysis of a large and high-quality survey conducted days before the second round of the 2018 election. It shows that racial identification and education interact to shape electoral preferences, above and beyond the usual suspects: (anti)partisanship, income, and geographic region. The analyses reveal differences in electoral preferences across racial groups, but these differences emerge only among the highly educated. Education interacts with racial identification, leading highly educated members of different racial categories to sympathize with opposing political camps.

Brazil’s 2018 election provides a useful opportunity to test these arguments and offers insights for the comparative study of racial politics and electoral behavior. By providing a more nuanced and complete picture of electoral support for Bolsonaro, this study deepens our understanding of opposition to far-right presidents in the global populist wave. In addition, given the contrasting perspectives on whether Bolsonaro politicized racial identities, this case offers an opportunity to assess and refine theories that attribute the electoral salience of social differences to top-down mobilization by political elites (e.g., Layton et al. Reference Layton, Smith, Moseley and Cohen2021; Posner Reference Posner2005).

In line with findings from elsewhere in Latin America (Madrid Reference Madrid2012), the findings of this analysis suggest that whether elites succeed in politicizing social differences may depend on the subjectivities that predominate within the electorate. Furthermore, these nuanced findings also provide an update on the Brazilian case as the go-to example of weakly politicized racial differences. The evidence uncovered here suggests that in recent years, Brazil has begun drifting toward a middle ground, where racial identification differentiates some voters, if not necessarily all.

The sections that follow first review the conventional wisdom that race is irrelevant to Brazilian electoral politics and introduce data that suggest the need for reconsideration and cast doubt on foregoing interpretations of Brazil’s 2018 election. Subsequent sections draw on insights from recent studies of racial subjectivity to develop the argument that racial identification and education interact to shape whether racial differences emerge in electoral preferences. The final two sections present empirical analysis and conclusions.

Reconsidering the Irrelevance of Race in Brazilian Elections

The election of Jair Bolsonaro to the Brazilian presidency in 2018 came as a shock to many observers, not only because the global wave of right-wing populism made its way to this once rising BRICS powerhouse, but also because Bolsonaro managed to prevail while explicitly employing racial appeals. Indeed, given Brazil’s longstanding national identity as a colorblind and harmonious “racial democracy,” scholarly wisdom has held that few social identities or differences—and certainly not race—had become significant bases of the party system or electoral competition.

Brazil’s open-list system of proportional representation is said to favor candidates who can individually amass as many votes as possible, incentivizing personalities over parties (Carey and Shugart Reference Carey and Shugart1995). Moreover, low seat allocation thresholds in the lower house of Congress (1.5 percent historically and 2 percent more recently) have been associated with party system fragmentation and electoral volatility (Mainwaring Reference Mainwaring1999). We might expect low thresholds to permit the formation of niche parties around relatively small constituencies, such as Brazil’s black population. Yet within the first decade following redemocratization, scholars argued that few social cleavages or identities were channeled into partisan affiliations or strongly predicted vote choice, let alone served as the basis for group-centered parties (Mainwaring Reference Mainwaring1999; Mainwaring et al. Reference Mainwaring, Meneguello, Power and Middlebrook2000; Samuels Reference Samuels2006).

To explain the low electoral salience of race in Brazil despite profound discrimination and inequalities, scholars pointed to Brazil’s national identity as a “racial democracy.” Too much has been written on the formation and consequences of Brazilian nationalism to do justice to this literature here.Footnote 2 Suffice it to say that “racial democracy” touted Brazil as a postracial society born from the mixture of African, European, and Indigenous peoples. Extensive race mixture and the blurring of racial boundaries have been cited as explanations for Brazil’s relatively harmonious relations between Brazilians of various skin tones—at least relative to the Jim Crow US South or Apartheid South Africa. And though social scientists have long denounced racial democracy as a myth that obscures the country’s deep and enduring racial inequities (Fernandes Reference Fernandes1965; Hasenbalg Reference Hasenbalg1979; Johnson Reference Johnson and Heringer2015; Nascimento Reference Nascimento1989; Paixão et al. Reference Paixão, Rossetto, Montovanele and Carvano2010; Paixão and Carvano Reference Paixão and Carvano2008), many claim that the myth is responsible for fluid and ambiguous racial subjectivities, the primacy of class-based considerations over racial ones, and the relatively weak politicization of racial differences in general (Bailey Reference Bailey2009; Guimarães Reference Guimarães1999; Hanchard Reference Hanchard1994; Marx Reference Marx1998; Telles Reference Telles2004).Footnote 3

To be sure, more recent scholarship has identified significant forms of race-based political activism and mobilization outside of the electoral arena (Bueno and Fialho Reference Bueno and Fialho2009; Caldwell Reference Caldwell2007; Perry Reference Perry2013; Smith Reference Smith2016), and in recent decades, shifts in state discourse and policies like affirmative action have signaled a shift in the state’s colorblind posture toward the racial question. But by and large, political scientists have maintained that, probably as a legacy of the racial democracy era, race has played no major role in Brazilian politics.Footnote 4

However, there are good reasons to question conventional wisdom on the electoral irrelevance of race in Brazil. First, efforts to understand if race matters in comparative contexts are almost always shaped by macrostructural expectations of politicized cleavages, such as those observed in the US African American vote or South Africa’s “racial census” (Dawson Reference Dawson1995; Ferree Reference Ferree2006). To be sure, Brazil’s electoral arena does not resemble the hypersalience of race found in the United States or South Africa. But why such anomalous outcomes should constitute a baseline threshold of political relevance against which all other cases are compared is unclear. As Clealand (Reference Clealand2017) argues, viewing racial politics dichotomously as either politicized or absent can obscure more nuanced analysis of how or in what distinct ways race might operate to shape political outcomes and behaviors in historically distinct contexts (Marx Reference Marx1998; also see Mitchell Reference Mitchell1977; Sawyer Reference Sawyer2005).

Second, another reason to question racial irrelevance is that many empirical studies that established the “political irrelevance” of race in Brazil were conducted before significant shifts in the Brazilian state’s posture toward the racial question, or in the context of an unconsolidated democratic regime and considerable political and economic instability. Indeed, 1990s Brazil saw severe hyperinflation and the impeachment of the first president democratically elected in nearly three decades. The situation stabilized by the late 1990s, but it was by studying the aftermath of this tumult that important work by Mainwaring (Reference Mainwaring1999) and Samuels (Reference Samuels2006) established the purported electoral irrelevance of race and other social identifications. In one instance, Mainwaring et al. (Reference Mainwaring, Meneguello, Power and Middlebrook2000, 200) conclude the irrelevance of race based on the absence of racial data altogether.Footnote 5

This scholarly rush to judgment on the race question is striking, seeing as how literacy requirements denied large swaths of the poor (and darker-skinned) population the right to vote until 1988 (Berquó and Alencastro Reference Berquó and Alencastro1992; Love Reference Love1970). With this in mind, it is unclear why one would expect unseasoned voters to emerge from two decades of military rule with fully formed electoral preferences, familiarity with the country’s voting process and complex electoral institutions, or established partisan sympathies that mapped cleanly onto racial or other lines.Footnote 6

Third, that race was electorally irrelevant was not a consensus view, and findings from analyses of the 1990s did not always comport with studies of earlier elections or those at different levels of government. Indeed, even studies conducted at the height of the state’s embrace of racial democracy—that is, when one might expect race to be especially irrelevant to voters—identify racial identification as a significant correlate of electoral preferences in national and state-level elections across several decades. Studies by Castro (Reference Castro1993), Soares and Silva (Reference Soares and Silva1987), and Souza (Reference Souza1971) all find that nonwhite voters are more likely than their white-identified counterparts to support leftist candidates or parties.Footnote 7 At the very least, we must acknowledge this empirical variation.

And finally, even if we grant that race was irrelevant in the decade following redemocratization, the social bases of the electorally dominant PT have since shifted and realigned. In 2002, the PT won the presidency with support from myriad social sectors, though its greatest support was concentrated in the industrialized Southeast region. But following the 2005 Mensalão corruption scandal—which embroiled the PT and cost it support from educated, middle-class voters—the party’s base of support swung toward poorer voters in the Northeast, who greatly benefited from the PT’s social program agenda (Hunter Reference Hunter2010; Hunter and Power Reference Hunter and Power2007). Given the high correlation between race, region, and class in Brazil, the shift in the PT’s electoral base also shifted support toward black and brown voters, who disproportionately populate the Northeast and lower-class strata (De Micheli Reference De Micheli2018; Telles Reference Telles2004). Collinearity, of course, means that one could interpret this realignment in different ways. But the point is that since the election of the PT to the presidency in 2002, Brazil’s electoral arena has stabilized and realigned around this partisan divide (Roberts Reference Roberts2014; Samuels and Zucco Reference Samuels and Zucco2018) in ways that had not yet occurred when conventional wisdom on the irrelevance of race was established.

This conventional wisdom has not only framed how scholars think about the role of race in Brazilian elections, but it also helps motivate both of the contrasting perspectives on the 2018 election outlined in the introduction. Whether one characterizes this election as “business as usual” (black and brown voters were entranced) or as a departure (Bolsonaro politicized race), one must take for granted the idea that race was not electorally salient before 2018. That is, one must assume or accept that what scholars argued in the 1990s remained true up until 2018. Sustaining this claim requires demonstrating that race was not salient, or at least was significantly less so, in previous electoral cycles—especially after the post-2002 realignment.

This point is most germane to a recent study conducted by Layton and colleagues (Reference Layton, Smith, Moseley and Cohen2021), who argue that Bolsonaro politicized race and other identities in 2018. According to these authors, top-down politicization explains the supposedly unprecedented correlation between racial ID and vote choice in this election. Analyzing the second round of voting, in which Bolsonaro faced off against PT candidate Fernando Haddad, the authors find a robust and significant negative relationship between black ID and Bolsonaro support. They further attribute this to resentment of policies that “coddle” black Brazilians—although this would seem to explain Bolsonaro support among nonblack voters, rather than black opposition. In any case, this study exemplifies the claim that Bolsonaro newly politicized race with his rhetoric and rests on the idea that race was not salient theretofore (also see Silva and Larkins Reference Silva and Larkins2019).

Analysis of election surveys does not support this claim. Figure 1 presents regression-adjusted estimates of the marginal effects of racial ID on support for the PT from 2002 to 2018. As expected, the data show no significant effect of race in 2002, except in the second round of voting, when black voters were less likely to support Lula relative to white voters. But the period following the realignment triggered by the 2005 corruption scandal is a different story. In 2006, black and brown voters are significantly more likely than white voters to support the PT in both first and second rounds of voting. In the following elections, this effect holds most consistently for black voters. In 2018, brown voters do not exhibit preferences significantly different from white voters on average, just as others have found (Almeida and Guarnieri Reference Almeida and Guarnieri2020; Amaral Reference Amaral2020; Layton et al. Reference Layton, Smith, Moseley and Cohen2021). But most important, the electoral preferences of black voters in 2018 were not different from 2014, when black voters were roughly 10 points more likely to support PT candidates in both rounds of voting (p < .05). Viewed in longer-term perspective, 2018 did not bring about the sudden politicization of race, but instead represents the continuation of a pattern that emerged after 2002. Claims that Bolsonaro entranced nonwhite voters, or was singularly responsible for black voters’ opposition to him, are dubious at best.

Figure 1. Marginal Effect of Racial ID on PT Vote, 2002–2018

Notes: Figure displays 95 percent confidence intervals. Estimates indicate support for PT candidates Lula (2002–6), Rousseff (2010–14), and Haddad (2018) and adjust for age, sex, region, income, education, religion, and party ID in all years except 2006, which did not collect party ID and religion. Full estimates available in appendix tables A1–A5.

Source: Data for this analysis come from the following CESOP surveys: 01838 (2002), 02551 (2006), 02717 (2010), and 02718 (2010); 03928 (2014); and 04577 (2018).

Brazil’s New Racial Subjectivity and Opposition to Bolsonaro

If racialized electoral preferences were not new in 2018, then how should we understand black ID as a significant correlate in this (or any earlier) election? Instead of relying on the singular presence of Bolsonaro or presuming that sociological differences find natural expression in the electoral arena, this study develops an explanation derived from Lee’s 2008 notion of the “identity to politics link.” This approach urges scholars to problematize the processes that politicize social identities and to consider that members of a social category may vary in the extent to which membership inspires political outlook or action (also see Clealand Reference Clealand2017). In the Brazilian case, this leads to updated accounts of racial subjectivity, which indicate that racial identification is a function of racial consciousness; some individuals choose to identify with specific racial categories because of their racialized worldviews (De Micheli Reference De Micheli2021). The implication for electoral behavior, I argue, is that how and whether race shapes preferences varies between and within racial categories. Only by incorporating updated findings from this literature can we make better sense of why racialized behavior was not new in 2018, and how racial identities are channeled and expressed in the electoral arena.

Recent shifts in Brazilians’ racial subjectivities are central to understanding why this is so. Traditionally, racial identification was said to be rooted in colorism—a logic of identification based on fine, color-based distinctions between individuals, rather than descent (Nogueira Reference Nogueira1998). Official racial categories were weakly institutionalized and did not match colloquial labels employed in everyday discourse (Bailey et al. Reference Bailey, Fialho and Loveman2018; Silva Reference Silva1996; Telles Reference Telles2004). Moreover, fluid boundaries and the absence of membership rules meant that individuals might identify with categories different from those ascribed to them, as well as change their identifications over time. This fluidity and ambiguity also permitted racial hierarchies—which valorize whiteness and stigmatize blackness—to incentivize whitening, in which Brazilians classify, or reclassify, in lighter racial categories when possible.

However, recent studies have documented significant change in this status quo. In the informal realm, use of the notoriously ambiguous term moreno is declining, whereas use of the capacious term negro, promoted by the black consciousness movement, is growing (Bailey and Fialho Reference Bailey and Fialho2018). Moreover, Brazilians are increasingly using official ethnoracial categories in open-ended identifications (Bailey et al. Reference Bailey, Fialho and Loveman2018). And in a reversal of the whitening thesis, Brazilians have exhibited an unmistakable tendency to adopt nonwhite, and especially black, identifications in recent decades (Jesus and Hoffmann Reference Jesus and Hoffmann2020; Miranda Reference Miranda2015; Soares Reference Soares, Theodoro, Jaccoud and Osorio2008).

Elsewhere (De Micheli Reference De Micheli2021), I attribute this reversal to expanded access to education for the lower classes, challenging the traditional view that upward mobility leads to whitening. Analysis of census data reveals that as lower-class sectors—those who are darker-skinned on average and who have racial options (Telles Reference Telles2014)—have gained unprecedented access to higher education, these upwardly mobile Brazilians have become more likely to “self-darken” rather than whiten. These findings comport with other recent studies, which have shown that once controlling for skin tone, education correlates positively with black identification (Telles and Paschel Reference Telles and Paschel2014; also see Mitchell-Walthour Reference Mitchell-Walthour2018).

More specifically, De Micheli Reference De Micheli2021 details that greater access to secondary and university education has brought individuals face to face with racial hierarchies and discrimination by increasing their personal exposure to new information, social networks, and labor market experiences. Through these direct and indirect pathways, greater education has increased individuals’ exposure to historical and statistical facts about slavery and racial inequality; a more capacious understanding of blackness, rooted in shared experiences of racism (rather than colorism); and greater discrimination and unrecognized status as they ascend the social ladder and compete for higher-status jobs and social positions. In turn, these personal experiences and perspectives have altered racial subjectivities and imbued racial identities with political meaning, fomenting racial consciousness and leading many to choose black identification. The analysis of national survey data confirms that education and skin tone interact to shape racial consciousness and that the racially conscious are most likely to opt for black identification over white or brown identification.

Though it is common to lump brown and black Brazilians in analysis, recent findings suggest that we should not necessarily expect the same racialized behavior from black- and brown-identified Brazilians.Footnote 8 Indeed, highly educated black (preto) identifiers, in particular, are those most associated with racial consciousness (De Micheli Reference De Micheli2021). This is probably due to a selection effect: individuals exhibiting racial consciousness often opt for black identification as a function of their political worldview. I do not intend to suggest that “black” or “brown” Brazilians occupy different or incomparable structural positions in Brazilian society, or that one is more or less subject to racial inequalities or discrimination than the other. The point is simply that racial identification is subjective, and we know from empirical research that it is black identification that is associated with distinctive levels of racial consciousness. For the purpose of understanding when certain voters make racial calculations, then, we have greater reason to expect black identification to impact behavior.

A second point relevant to the study of identity-motivated electoral behavior is that the black racial category is heterogeneous, comprising individuals who embrace the traditional colorist understandings of race, as well as race-conscious and politically oriented identifiers who may less clearly meet phenotypical criteria for blackness but identify as such nonetheless. Education is a significant factor that sets these politically motivated identifiers apart—not because education necessarily leads to enlightened, “correct,” or rational perspectives; it is simply these voters for whom racial considerations are more likely to be top of mind—the racially conscious.

Thus, both educational status and racial identification must be taken into account when hypothesizing where or among whom racial differences are likely to emerge. In this view, one can expect race-conscious voters (i.e., highly educated black identifiers) to be especially responsive to Bolsonaro’s racist rhetoric and thus less likely to support Bolsonaro than those for whom racial considerations may not be top of mind.Footnote 9 This latter group can include less educated black voters, probably motivated more by economic concerns than racial issues per se, as well as voters in other racial categories, who tend to exhibit less racial consciousness (De Micheli Reference De Micheli2021). This would lead us to expect education-based variation within the black category in particular, and leads to the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1. Education will decrease support for Bolsonaro among black voters.

Hypothesis 1a. Among black voters, the highly educated will be less likely than the less educated to support Bolsonaro.

Conversely, we can also assess the implications of hypothesis 1 and the idea of education-based variation within racial categories by analyzing toward which candidates opposition to Bolsonaro is diverted. As discussed earlier and as figure 1 illustrates, there is a history of black voters’ associating with leftist parties and candidates (Castro Reference Castro1993; Soares and Silva Reference Soares and Silva1987; Souza Reference Souza1971). More recently, there is reason to think race-conscious voters might be likely to reward the PT for progress made on racial issues, including appointing black movement activists to cabinet posts, creating a federal agency for racial equity, and promoting affirmative action legislation (Paschel Reference Paschel2016). But at the same time, many educated voters abandoned the PT due to allegations of corruption, black voters included (Hunter and Power Reference Hunter and Power2007). Thus, among voters committed to the left, less educated black voters are likely to remain loyal to the PT as beneficiaries of its social program agenda (De Micheli Reference De Micheli2018), whereas better educated black voters are likely to seek alternatives to both Bolsonaro and the PT.

In 2018, leftist Ciro Gomes (PDT) mounted a significant challenge to the PT, siphoning off significant support, probably dividing educated black support across leftist candidates, and obscuring leftist tendencies among highly educated black voters. Acknowledging this reality and expanding on the idea that the effect of racial identification on electoral preferences varies within racial categories, we can also expect the following among black voters:

Hypothesis 1b. Among black voters, the highly educated will be more likely to support leftist candidates than the less educated.

Understanding this within-group variation can also shed light on when differences in electoral preferences are likely to emerge between racial groups. It stands to reason that we may observe fewer racial differences in electoral preferences among poor and less educated voters, many of whom share economic considerations. Moreover, less educated voters have been shown to be less race-conscious. Therefore, whether these voters are more likely to remain loyal to the PT’s social program agenda (De Micheli Reference De Micheli2018; Hunter and Power Reference Hunter and Power2007) or defect in support of Bolsonaro, there is reason to expect poor voters of all stripes to be more united in their electoral preferences.

Among the highly educated, however, differences between racial groups are likely to emerge, due to the divergent effects of education on the preferences of voters in different racial categories. In contrast to highly educated black voters, highly educated white voters may exhibit greater support for Bolsonaro (and conservatives) than less educated counterparts. There are two main reasons for this. First, since they have not been targeted with racist rhetoric, white voters have less reason to oppose Bolsonaro on racial grounds, and they may even agree with his rhetoric or views (see Layton et al. Reference Layton, Smith, Moseley and Cohen2021). Second, highly educated white voters abandoned the PT in large numbers after the Mensalão scandal and have since exhibited high levels of anti-PT partisanship (Hunter and Power Reference Hunter and Power2007; Samuels and Zucco Reference Samuels and Zucco2018).

Anticorruption preferences are said to be central to the PT’s loss of educated support, and were a centerpiece of Bolsonaro’s 2018 campaign. Therefore education is likely to move black and white support in different directions. We can expect a certain baseline of electoral cohesion among less educated voters of all stripes, who are likely to behave similarly, due to shared economic considerations or political loyalties. From this baseline, we ought to observe that education increases white support for Bolsonaro, whereas education increases black support for the left. Consequently, the racial gap between white and black voters in Bolsonaro support should widen with greater education. We can formally state these predictions as follows:

Hypothesis 2. Education will moderate the racial gap in Bolsonaro support among white and black voters.

Hypothesis 2a. Among the highly educated, black voters will be less likely than white voters to support Bolsonaro.

Hypothesis 2b. Differences between white and black voters in Bolsonaro support will be greatest at high levels of education.

In addition, it bears repeating that I do not make specific predictions about brown-identified voters and do not simply assume that their behavior mirrors that of black voters. As we have seen, recent research indicates that brown and black Brazilians do not exhibit the same levels of racial consciousness. My 2021 analysis reveals that brown Brazilians appear closer to whites than blacks in this regard. From this perspective, it seems less likely that race would be top of mind for brown voters, and they may consequently behave more like white voters. Either way, this study includes brown voters in the analysis but makes no specific predictions about their behavior.

Analysis

These hypotheses are tested with analysis of high-quality public opinion data collected by the firm Datafolha.Footnote 10 This survey was fielded on October 24 and 25, 2018, days before the second round of voting on October 28 and soon after the first round of voting on October 7. The survey included voter preferences for both rounds and contained a large, nationally representative sample of 9,137 observations. A sample of this size is critical for testing the hypotheses specified here to ensure sufficient observations across educational strata within each racial group. This is a distinct advantage of these survey data, since many national surveys (e.g., LAPOP or Latinobarometer) typically contain far fewer observations and few black-identified respondents. Such samples are not adequate for detecting the type of sectoral effects hypothesized here. This sample includes 1,366 black respondents, 299 of whom completed university.

Dependent Variables

The dependent variable in this study is Vote choice. First- and second-round preferences were analyzed. Vote choices were self-reported and were measured retrospectively for the first round and prospectively for the second. In analysis of the second round, respondents were coded as supporting Bolsonaro (1) or PT candidate Fernando Haddad (2) or casting blank or spoiled ballots (3). In the first round, respondents were coded as supporting Bolsonaro (1), Haddad (2), Ciro Gomes (3), Geraldo Alckmin (4), other candidates (5), or casting blank or spoiled ballots (6).

Gomes and Alckmin finished in third and fourth place, respectively, in the first round. All other candidates received less than 4 percent of the vote in the first round and were included as “other.” Gomes, of the Democratic Labor Party (PDT), represented a left-wing ideological alternative to the center-left PT candidate, Haddad. Alckmin represented the Brazilian Social Democratic Party (PSDB). The PSDB was formerly the center-right competitor to the PT, but lost significant electoral support to Bolsonaro in 2018. Estimating support for these alternatives to Bolsonaro and Haddad will enable testing of hypothesis 1b.

Independent Variables

The independent variables of interest are Racial identification and Education. Racial ID was measured as self-declaration in an official census category: white (1), brown (2), and black (3). Yellow and Indigenous respondents were not analyzed. No additional racial or color data were collected in this survey. Education was measured as the highest level of education completed: 1) less than primary, 2) primary, 3) high school, and 4) university or more. Following my previous work (De Micheli Reference De Micheli2021), I considered “high education” to be high school and university education. In the analyses, education and racial ID were interacted to test the hypotheses. In assessing the hypotheses, I took as evidence of “racial voting” statistically significant differences in electoral support that emerged between racial categories. Similarly, educational variation within racial categories was understood as statistically significant differences by level of education.Footnote 11

All analyses included standard demographic controls: age, gender, household income, and religion. Also included were fixed effects for region and the size and type of municipality in which respondents vote.Footnote 12 Models also controlled for respondents’ partisan affiliations, a well-known predictor of electoral behavior: 1) nonpartisan, 2) PT, 3) PSDB, 4) MDB, 5) PSL, or 6) other. Samuels and Zucco (Reference Samuels and Zucco2018) find that racial ID correlates with PT partisanship. It is therefore important to control for partisanship to reasonably isolate the effects of racial ID.

In addition, a proxy was included for anti-PT affect, the prominent form of antipartisanship in Brazil. Unfortunately, the Datafolha survey does not provide a measure similar to either Layton et al. (Reference Layton, Smith, Moseley and Cohen2021) or Samuels and Zucco (Reference Samuels and Zucco2018). Instead, open-ended explanations of vote choice provided by respondents were coded. Respondents were coded as anti-PT if reasons given for their vote included that they rejected or did not like the PT; wanted anything but a PT government; wanted to see the PT lose; or voted primarily to oppose the PT. Respondents provided a maximum of seven reasons for their choice. If any of these included the above phrases, they were coded as anti-PT (1) and otherwise not (0).

Models and Estimation

The models used multinomial logistic regression to analyze the categorical dependent variables. Estimates presented here were computed from models that included an interaction term between education and racial identification, which allows for assessment of the relevant comparisons between and within racial categories. Full model estimates and estimates from noninteractive models can be found in the online appendix, tables A5 and A6. Relevant estimates are presented in graphical form; all estimates include the full set of control variables and are survey-weighted. Predicted probabilities and marginal effects are computed as average partial effects (Hanmer and Kalkan Reference Hanmer and Kalkan2013), and unless otherwise noted, all figures display 95 percent confidence intervals.

Results

The models estimate that black voters, on average, were less supportive of Bolsonaro in both rounds of voting. In the first round, roughly 46 percent of white and brown voters supported Bolsonaro, compared to 37 percent of black voters (p < .001). In the second round, roughly 56 percent of white and brown voters supported Bolsonaro, compared to 45 percent of black voters (p < .001). This difference of roughly 10 points between black and nonblack voters replicates the direction and significance of estimates computed from other survey samples (Almeida and Guarnieri Reference Almeida and Guarnieri2020; Layton et al. Reference Layton, Smith, Moseley and Cohen2021).Footnote 13 In both rounds of voting, differences emerge only between black and nonblack voters, on average.

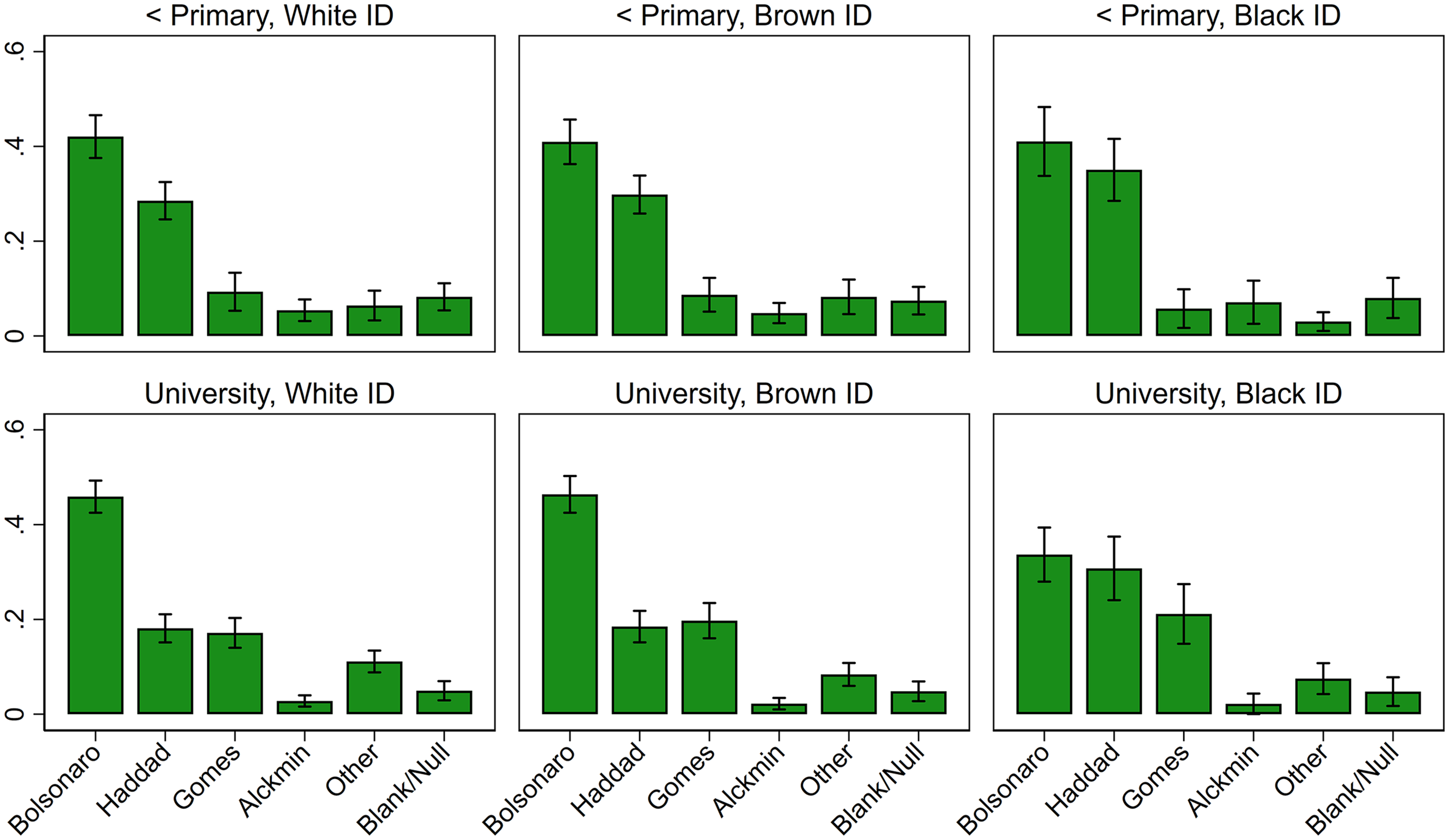

Figure 2 presents predicted probabilities of Bolsonaro support in both rounds of voting by racial ID and education. At first glance, two trends are apparent. First, Bolsonaro receives majority support only from white and brown voters, and in the second round, this is true at all levels of education. Bolsonaro does not receive majority support from black voters in either round of voting, or at any level of education. Second, there are positive, if nonmonotonic, relationships between education and Bolsonaro support among white and brown voters, but this is not the case for black voters.

Figure 2. Predicted Probabilities of Bolsonaro Support by Racial ID and Education

Hypothesis 1 predicts that among black voters education will decrease support for Bolsonaro, and more specifically, hypothesis 1a predicts that highly educated black voters will be less likely to support Bolsonaro compared to less educated black voters. Point estimates for highly educated black voters are lowest when compared to other combinations of race and education. In the first round, 38 and 34 percent of high school– and university-educated black voters, respectively, support Bolsonaro. By comparison, roughly 41 percent of the least educated voters in all racial categories support Bolsonaro in the first round. The seven-point difference between university-educated black voters and the least educated white and brown voters is statistically significant (p < .05). This difference among black voters is not significant (p = .12), although these estimates are less efficient. In the first round of voting, point estimates move in the hypothesized direction, but the variation predicted by hypothesis 1a does not reach conventional levels of significance. In the second round, there is even less suggestive evidence to support hypothesis 1a, though university-educated black voters are again estimated to be least supportive of Bolsonaro (44 percent). This is only one point lower than the least educated black voters, and this difference is not statistically significant.

In contrast to these findings among black voters, there is a positive relationship between education and Bolsonaro support among white voters beause Bolsonaro derived the greatest support from high school–educated voters in this racial category. Compared to the least educated white voters, the high school–educated are eight points and ten points more likely to support Bolsonaro in the first and second rounds, respectively (p < .01). Among brown voters, point estimates for Bolsonaro support increase slightly with education, but these differences are not statistically significant.

Analysis of these data does reveal variation within racial categories by education, but this variation does not support the predictions of hypothesis 1a. Though in the first round point estimates do decrease as expected, this is not the case in the second round, when the outcome of the election is at stake. Moreover, the effect of education on within-group variation is clearest among white voters, who become more supportive of Bolsonaro with education. Instead of driving down support for Bolsonaro, black identification appears to serve as a buffer against the positive effect of education among white voters.

Hypothesis 1b predicts that highly educated black voters will be more likely than their less educated counterparts to support left-wing candidates in the first round, when “the voter can and does freely express his first preference” (Giovanni Sartori (1994) quoted in Cox Reference Cox1997, 125). Figure 3 displays predicted probabilities of the choices facing voters in the first round by racial ID and at the highest and lowest levels of education. Again, we find that Bolsonaro secures a significant share of first-round support from white and brown voters at high and low levels of education. Among these voters, PT candidate Haddad fares significantly better among those with low education (30 versus 18 points, p < .001). Moving from low to high education among white and brown voters has a limited effect on Bolsonaro support (which peaks among the high school–educated), decreases support for Haddad (p < .05), and increases support for leftist alternative Gomes (p < .05).

Figure 3. First Round Electoral Preferences by Racial ID and High/Low Education

Black voters’ first-round preferences, on the other hand, differ from those of other voters and respond differently to changes in education. First, unlike white and brown voters, black voters with low education are split in their support for Bolsonaro and Haddad (41 versus 35 points, respectively, p = .35). Though Bolsonaro slightly edges out Haddad, this is unlike the result for white and brown voters, who clearly prefer Bolsonaro over all other candidates (p < .05).

Second, moving from low to high education among black voters increases support for Gomes (6 versus 21 points, p < .001), but unlike other voters’ choices, this does not come at the expense of support for Haddad. Instead, increased support for the leftist alternative derives from the (insignificant) decrease in Bolsonaro support, along with decreases in other outcomes. Bolsonaro edges out Haddad among highly educated black voters (34 versus 31 percent). But this difference is not significant, and Bolsonaro support is far from a majority preference among highly educated black voters, who are split between support for the two major left-wing candidates, Haddad and Gomes. As a point of comparison, among no other cross-section is combined support for conservative candidates Bolsonaro and mainstream alternative Alckmin similarly divided: Bolsonaro receives the lion’s share of electoral support on the right.

To more clearly assess how racial ID and education shape left-right voting, figure 4 displays the combined probability of supporting either Haddad or Gomes in the first round of voting. Among white and brown voters, combined support for either leftist candidate falls short of Bolsonaro support (45 percent), and there is no statistical relationship between education and leftist support. Among black voters, by contrast, there is a positive relationship between education and leftist support. Among the university-educated, support for one of these two leftist candidates exceeds Bolsonaro support in the first round: 52 percent support Haddad or his leftist competitor Gomes, compared to 36 percent who support Bolsonaro or his conservative competitor Alckmin (p < .05).

Figure 4. First–Round Leftist Candidate Support by Education and Racial ID

An analogous figure combining Bolsonaro and Alckmin support in the first round is provided in the appendix (figure A1), and reveals mirrored patterns. Majorities or near-majorities of white and brown voters prefer a conservative candidate in the first round with little variation by education. Among black voters, only a near-majority of the least educated supports a conservative candidate, and education correlates negatively with conservative candidate support. University-educated black voters are least likely to support Bolsonaro or Alckmin. Closer examination of first-round preferences supports hypothesis 1b. Insofar as racial preferences vary among black voters by education, this more clearly bolsters support for the left in general than it decreases support for the conservative Bolsonaro.

Hypothesis 2 predicts that education will moderate the racial gap in Bolsonaro support, and hypothesis 2a further specifies that among the highly educated, black voters should be less likely than their white counterparts to support Bolsonaro. Predicted probabilities in figure 2 provide support for this hypothesis. In the first round, 34 percent of university-educated black Brazilians support Bolsonaro, compared to 46 percent of their white and brown counterparts (p < .001). Similarly, 38 percent of high school–educated black voters support Bolsonaro, compared to 50 and 48 percent of their white and brown counterparts, respectively (p < .001). Similar patterns are evident in the second round of voting. Among the university-educated, 44 percent of black voters support Bolsonaro, versus roughly 54 percent of white and brown voters (p < .01). Among the high school–educated, 45 percent of black voters support Bolsonaro, versus 61 and 57 percent of white and brown voters, respectively (p < .001).

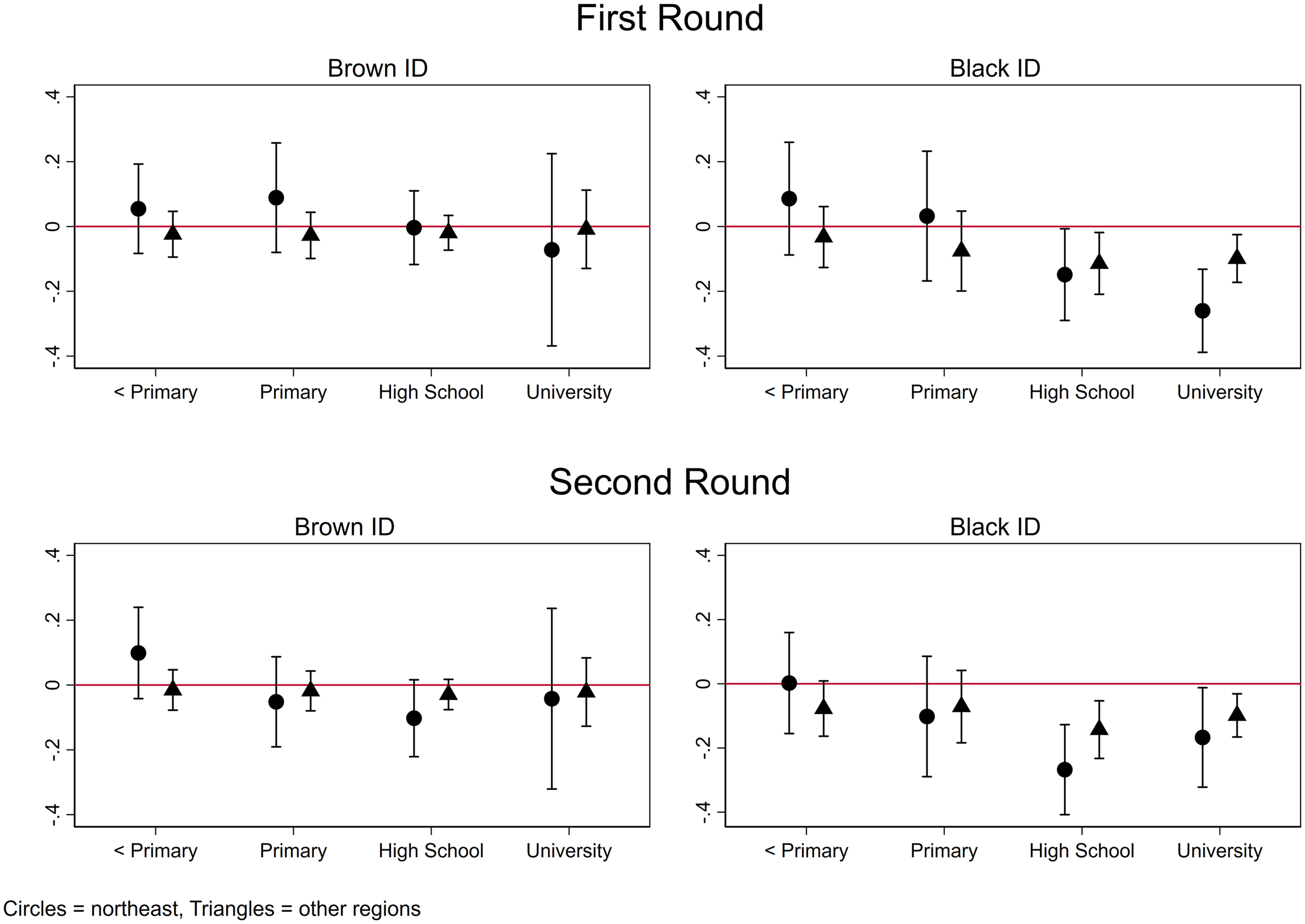

Hypothesis 2b specifies that differences between racial groups in Bolsonaro support should be greater among the high school– and university-educated. Figure 5 presents the marginal effect of racial ID on Bolsonaro support across education levels and in both rounds of voting, comparing the effects of racial ID within educational strata. The left-hand panels show the effects of brown ID compared to white voters, with no major differences across these racial categories at any education level. Only brown voters with high school education are estimated to be less supportive of Bolsonaro (p < .1). This is driven more by the boost in Bolsonaro support among white high school–educated voters (figure 2), and as we will see, this effect does not hold up to further scrutiny.

Figure 5. Marginal Effects of Racial ID (vs. White ID) on Bolsonaro Support

Among black voters, we find the predicted pattern. The negative effects of black ID on Bolsonaro support increase in magnitude as education increases, and indeed, among the less educated, there are no statistically significant differences across racial groups in support for Bolsonaro. In the first round, high school– and university-educated black voters are estimated to be 12 points less likely to support Bolsonaro compared to their white counterparts (p < .001). In the second round, these voters are 16 and 10 points less likely to support Bolsonaro compared to their white counterparts (p < .01). The differences between these marginal effects are not statistically significant. Overall, these findings support hypothesis 2. Not only does the racial gap widen with education, but racial differences emerge only among black and nonblack voters with high education.

Robustness Check: Disentangling Race and Region

The evidence presented here supports three of the four hypothetical predictions, but doubts may linger as to whether the estimated effects of racial identification are confounded by collinearity with geographic region in Brazil. As noted, the PT’s base of support post-2002 swung significantly from the industrialized Southeast (which is majority white) to the less developed Northeast (which is majority nonwhite).

Findings of Almeida and Guarnieri (Reference Almeida and Guarnieri2020) support the notion that the estimated effects of race in the 2018 election might be confounded by region. These authors report that nonwhite voters in the Southeast were significantly more likely to support Bolsonaro than those in the Northeast, though it is not clear whether they lump together brown and black voters. In any case, although region is controlled for in all estimates presented here, collinearity between these two variables may nonetheless undermine attempts to disentangle these effects from observational data and may raise questions as to whether estimates computed from the full sample are driven by respondents located in the Northeast.

To address these possibilities, the sample was divided into Northeast and non-Northeast subsamples and estimates computed separately from each subsample were compared. On one hand, we might expect these patterns to hold only in the Northeast, where support for the PT is known to be higher and where highly educated black voters might be especially likely to oppose Bolsonaro. Alternatively, support for the PT might be so strong and widespread in the Northeast that we might not observe the hypothesized pattern in this region. Either way, separating out Northeastern respondents will allow us to assess whether the findings apply to or are driven by this region.

Figure 6 replicates the quantities of interest in figure 5, comparing respondents across racial categories within educational strata.Footnote 14 Comparing estimates computed from Northeast and non-Northeast samples shows no major variation in the size, significance, or direction of the effects presented above. In two instances among black voters (first-round university and second-round high school voters), the magnitude of the point estimate is amplified in the Northeast but is still significant in other regions. Furthermore, in both rounds of voting and in all geographic regions, the negative relationship between racial ID and Bolsonaro support remains driven by highly educated black voters. Racial identification influences vote choice, but only for black voters with high levels of education. Main findings are not unique to or dependent on Northeastern respondents.

Figure 6. Marginal Effects of Racial ID (vs. White ID) on Bolsonaro Support by Region

Conclusions

The role that race played in Brazil’s 2018 election cannot be characterized as an instance of sudden electoral salience, or as conforming to the conventional wisdom that race is electorally irrelevant in the country. Bolsonaro’s inflammatory rhetoric was indeed unprecedented and aberrational in Brazil, but voter behavior in 2018 did not depart from the longer-term pattern of racialized preferences in recent elections. Instead, this analysis has revealed that the effects of racial identification on electoral behavior are conditional on educational status. In both rounds of voting, black voters were less likely than white or brown voters to support Bolsonaro, on average. But these average differences were driven by highly educated black voters (those who exhibit greater racial consciousness, recent studies tell us). In the first round of voting, moreover, university-educated black voters in particular exhibited distinctive support for leftist candidates, rather than Bolsonaro or a conservative alternative. Close analysis of the 2018 election has provided an opportunity to better understand the racialized dynamics of electoral behavior in this context and to draw out the implications of Brazil’s shifting racial subjectivity for electoral behavior.

Beyond the 2018 election, secondary findings presented here—namely, that race has correlated significantly with vote choice since 2006—should caution scholars against taking past conventional wisdom for granted without updating expectations in light of social and political developments in a given case. In Brazil, both the post-2002 realignment and the well-documented shift in racial subjectivities demand renewed and more careful consideration of the role race plays in Brazilian elections. The relevant question is not if but for whom race matters.

Even beyond the Brazilian case, this study also highlights what is to be gained by incorporating identity subjectivity and formation processes into our expectations of electoral behavior, as Lee (Reference Lee2008) has urged. Doing so helped to better specify in what ways race was “politically relevant” in a context where race has not served as a kind of master political cleavage, as in in the United States or South Africa. In light of these findings, future research on political behavior in Latin America might consider how similar patterns, or those related to other subjectivities, might operate to shape patterns of electoral behavior, including outcomes beyond vote choice. Indeed, this analysis seems to indicate that even amid the tumult of the 2018 election, black voters exhibited greater stability in their electoral preferences than other voters did. Verifying such claims lies beyond the scope of this article, but examination of racialized patterns of partisan and electoral stability over time would be welcome additions to the literature.

Furthermore, the more limited politicization of racial identities observed in Brazil’s 2018 election—a context that might be thought of as a likely case for intergroup politicization—carries implications for theorizing about the role of elites in identity politicization processes, at least in Latin America. Influential theorizing attributes the electoral salience of social differences to institutionally or demographically derived incentives of political elites, who mobilize differences from above to maximize postelectoral payoffs (e.g., Huber Reference Huber2017; Posner Reference Posner2005). And though they acknowledge and call for greater attention to the societal changes that probably preceded Bolsonaro’s mobilization of racial differences and affect, Layton et al.’s Reference Layton, Smith, Moseley and Cohen2021 analysis of the 2018 election similarly centers Bolsonaro as a political elite capable of bringing social differences to the fore through top-down campaign strategy.

But the empirical record in this case does not fit this framework. Instead, racial differences emerged conditionally and only among a specific subset of voters already likely to respond to racial rhetoric or appeals. In some contexts, elites may politicize social cleavages from above with relative ease. But the evidence uncovered here suggests that we cannot always assume that elites dictate the terms and resonance of the appeals they employ. Just as Madrid (Reference Madrid2012) argues in the case of ethnopopulist parties in the Andes, elites seeking to craft campaign strategies along demographic lines may face constraints from below, based on the subjectivities that voters themselves bring to bear on the electoral arena.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/lap.2023.8

Supporting Information

Additional supporting materials may be found with the online version of this article at the publisher’s website: https://doi.org/10.1017/lap.2023.8