Human milk is considered the optimal source of nutrition and disease prevention for infants throughout the first year of life( Reference Lessen and Kavanagh 1 ). The WHO and the American Academy of Pediatrics recommend infants be exclusively breast-fed for the first 6 months, with continued breast-feeding for the first year or longer( 2 , 3 ). Human milk offers health, environmental and economic benefits for the infant, mother and community( Reference Bartick and Reinhold 4 ). In the USA, 81 % of infants are ever breast-fed; at 6 months only 52 % of infants are still breast-fed, 22 % exclusively( 5 ). Returning to work affects breast-feeding rates, especially when working full-time( Reference Mirkovic, Perrine and Scanlon 6 – Reference Kimbro 8 ). For example, women returning to work any time within 6 months postpartum have a statistically significant higher hazard for breast-feeding cessation during the first 6 months (hazard ratio=1·46) compared with those who do not return( Reference Dagher, McGovern and Schold 9 ). More specifically, the month women return to work, they have 2·2 times the odds of ceasing breast-feeding compared with women who did not return to work in that month( Reference Kimbro 8 ).

Likely because of high rates of mothers’ return to work postpartum, most infants in the USA (72 %) are under some type of non-parental care( Reference Kim and Peterson 10 ) and about 15 % of those less than 1 year old attend a centre-based programme( 11 ). While return to work seems to increase risk for early breast-feeding cessation, childcare-related support for breast-feeding appears to be protective. For example, one study found breast-feeding at 6 months was positively associated with childcare providers’ support for feeding expressed milk and breast-feeding on-site( Reference Batan, Li and Scanlon 12 ). Yet, we know of no licensing or regulation requirements for breast-feeding-related support.

The US Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Support Breastfeeding identified childcare providers as essential in supporting mothers to continue breast-feeding after returning to work and urged states to adopt the national standards outlined in Caring for Our Children: National Health and Safety Performance Standards ( 13 , 14 ). The standards include training staff to support a mother’s plan to provide her own milk and providing mothers with (i) a place to breast-feed during work and (ii) a private area to pump milk( 14 ).

US governmental support for breast-feeding-friendly childcare is similar to that embraced by other countries, including Australia( 15 , Reference Javanparast, Newman and Sweet 16 ), the UK broadly( 17 ) and differentially in Scotland( Reference Pearce, Li and Abbas 18 ). Moreover, it is consistent with the WHO’s 2003 Global Strategy for Infant and Young Child Feeding, which emphasized childcare facilities as having ‘potentially important roles’( 19 ). In Australia, the national breast-feeding strategy recommends pilot testing a breast-feeding-friendly childcare designation programme( 20 ). While evidence exists that most childcare providers are unaware of it, Australian law protects breast-feeding women from discrimination, including in childcare settings( Reference Smith, Javanparast and McIntyre 21 ). In the UK, guidelines from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence suggest that caretakers in nurseries and other pre-school settings should ensure that breast-feeding mothers are able to breast-feed ‘when they wish’ and are ‘encouraged to bring expressed breast milk’( 17 ). Specifically, in Scotland, the national policy has implications for the role childcare providers can play in supporting continuation of breast-feeding among mothers who plan to return to work( Reference Dombrowski, Henderson and Leslie 22 ). To ensure this, several breast-feeding promotion schemes in nurseries and childcare centres have been launched by the National Health Service, including the Breastfeeding Friendly Nursery Programme in 2001 and the Breastfeed Happily Here project in 2008. The Breastfeeding Welcome scheme, launched by the National Childcare Trust, has more childcare centres participating to encourage breast-feeding in centres than the National Health Service schemes( Reference Dombrowski, Henderson and Leslie 22 ).

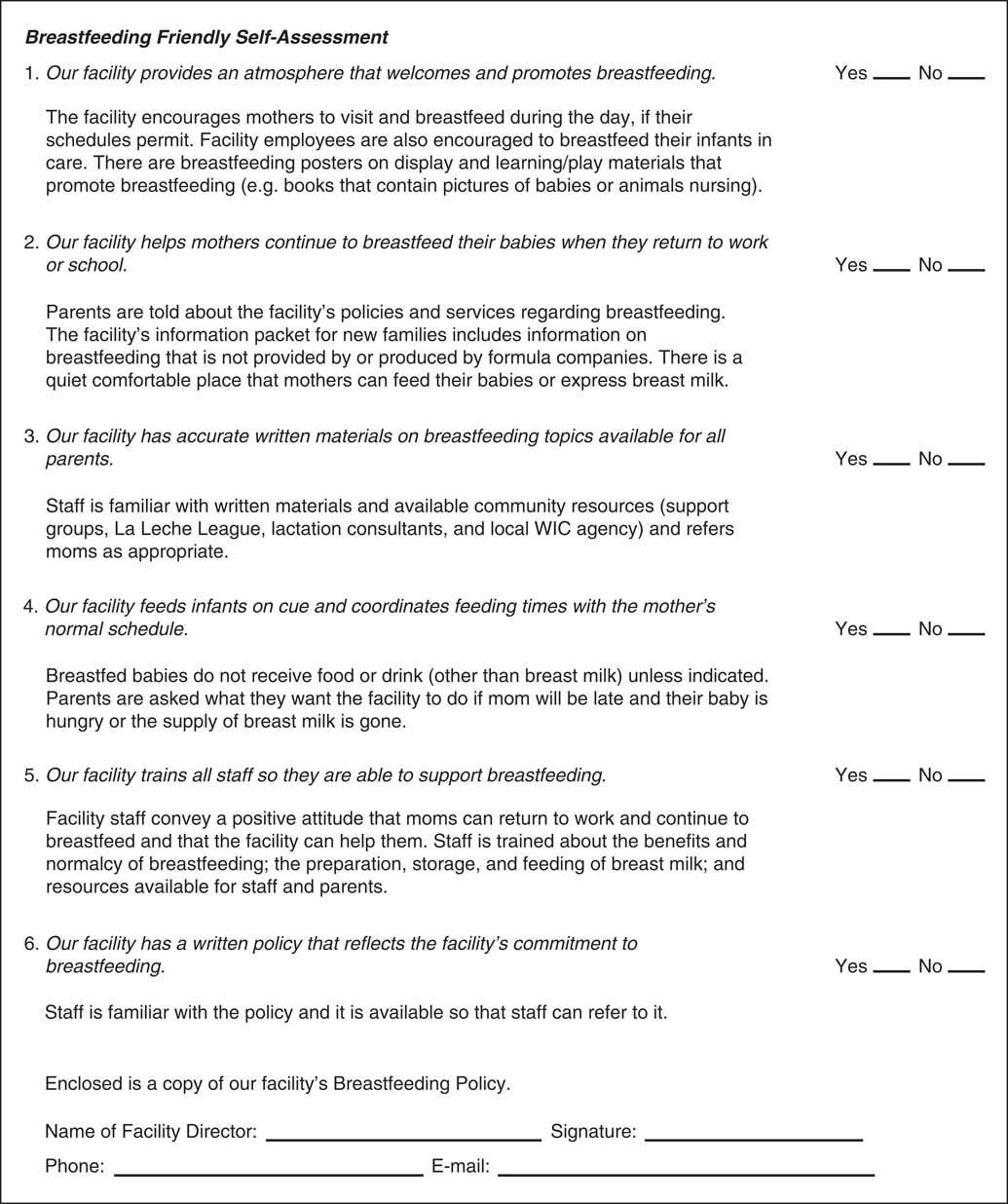

In response to the US Surgeon General’s call, efforts to formally recognize breast-feeding-friendly childcare centres have emerged in several states( 23 ). The present study focuses on childcare centres in Florida. Established in 2012 to support Florida’s breast-feeding law( 24 ), the Florida Breastfeeding Friendly Childcare Initiative (FL-BFCCI) was developed by the Florida Breastfeeding Coalition and the Florida Department of Health (FDOH) office of the Child Care Food Program (CCFP), which provides healthy foods to children at centres that meet family income requirements. Designed to encourage childcare centres to be ‘breastfeeding friendly’, FL-BFCCI designation is achieved by: (i) completing a free, 16 min, asynchronous web-based training covering breast milk characteristics, handling and storage guidelines, and hunger cues (recommended but not required); (ii) submitting a breast-feeding-friendly policy; and (iii) submitting a one-page self-assessment of requirement completion (Fig. 1)( 24 ). To date, there are 284 centres designated, out of 6798 centres state-wide (K Schoen, unpublished results), yet there is no available evidence demonstrating childcare administrators’ awareness and perceptions of the FL-BFCCI. This is similar to the dearth of evidence we found regarding administrators’ awareness and perceptions of breast-feeding initiatives in places such as Australia, the UK broadly and Scotland specifically. The most closely associated research we found was conducted in New Zealand, where it was demonstrated that few childcare managers (23 %) and staff (30 %) were aware of the Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI)( Reference Manhire, Horrocks and Tangiora 25 ).

Fig. 1 Florida Breastfeeding Friendly Childcare Designation Self-Assessment Form( 24 ) (WIC, Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children)

The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) provides a systematic method of assessing potential barriers to and facilitators of implementing an innovation within an organization( Reference Damschroder, Aron and Keith 26 ). Developed in 2009, the CFIR is a ‘menu of [thirty-nine] constructs’( 27 ) within five domains: (i) Intervention Characteristics; (ii) Outer Setting; (iii) Inner Setting; (iv) Characteristics of Individuals; and (v) Process. Research has tied each CFIR construct to effective implementation of innovations primarily related to health and health care. The CFIR has been used across a variety of settings( Reference Kirk, Kelley and Yankey 28 ), to aid in planning to implement new innovations as well as understanding implementation outcomes. As reported in a 2016 systematic review, early studies using the CFIR were characterized by qualitative or mixed-methods designs, perhaps aided by the CFIR Interview Guide Tool( 29 ). More recently, however, quantitative assessment of the CFIR domains has become more common( Reference Fernandez, Walker and Weiner 30 – Reference Clinton-McHarg, Yoong and Tzelepis 32 ). Consistent with the original recommendations provided for CFIR application( Reference Damschroder, Aron and Keith 26 ), in the 2016 review, few study teams assessed all domains and constructs.

As the CFIR is relatively new, to our knowledge, it has not been applied to breast-feeding innovations. Moreover, we found only one application of the CFIR in childcare settings. In a cross-sectional study, Wolfenden et al.( Reference Wolfenden, Finch and Nathan 33 ) quantitatively examined CFIR factors in relation to implementation of a nutrition and physical activity programme for children aged 3–5 years in Australian childcare centres. They found that variables related to four of thirteen examined CFIR constructs were statistically significantly related to implementation of their initiative and pointed to the need for additional studies to inform implementation of interventions in the childcare setting.

The present analysis aimed to identify possible avenues for supporting successful implementation of BFCCI throughout the USA; thus it explored awareness of the FL-BFCCI among childcare centre administrators from the Tampa Bay area, FL, and employed the CFIR to examine their perceptions of barriers to and facilitators of potential implementation of the initiative.

Methods

Participation

Childcare centre administrators were recruited from a list of childcare centres in the Tampa Bay area (i.e. Hillsborough and Pinellas counties, FL) obtained through the FDOH. All participating administrators (Table 1) were required to provide permission for staff to complete a related survey (results not reported here). In the summer of 2015, all 190 identified centres in the area were mailed an introductory letter and were telephoned at least once during recruitment efforts. During those phone calls, eligibility screening was conducted to confirm: (i) centres enrolled infants; and (ii) administrators were ≥18 years old. One hundred and twelve (58·9 %) directly refused to participate, forty-seven (24·7 %) neither refused nor agreed to participate, thirty-one (16·3 %) agreed to participate during the recruitment call, but ultimately twenty-eight (14·7 %) consented and completed the in-person interview. Interviews were completed until we reached data saturation, when the team determined that no new information was arising from the interviews (n 28). Reasons for non-participation were not systematically tracked, but included the centre not serving infants and general disinterest in research participation.

Table 1 Participant characteristics and pseudonyms, with centre characteristicsFootnote *, of the childcare centre administrators (n 28) from the Tampa Bay area, FL, USA, interviewed in 2015

* If data were missing, participant was excluded from summary calculation.

† Calculations were based on the highest number given.

Data collection

After the recruitment phone call, interviews were conducted in-person at the childcare centres by trained research staff at the convenience of the administrators. Interviews included structured questions and then a semi-structured portion; only the semi-structured portion is the focus of the present investigation. In the semi-structured portion, administrators were asked about their awareness of the FL-BFCCI innovation. Regardless of their responses, all administrators were asked to review a handout summarizing FL-BFCCI criteria before the interview proceeded. The handout defined the term ‘breastfeeding friendly’ and listed the primary sentence for each of six criteria for FL-BCCI designation (see Fig. 1 for criteria), but not the descriptions provided on the self-assessment form( 34 ). In the remainder of the semi-structured interview, administrators were asked about the fit and potential implementation of the FL-BFCCI within their organization, guided by the CFIR (see below).

Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed for analysis with pseudonyms assigned to each transcript. Interviews lasted approximately an hour; participating administrators received a $US 50 gift card. During a separate phone call, centre staff reported on fees for full-time childcare of a 6-month-old child and participation in the US Department of Agriculture (USDA)-sponsored and FDOH-administered CCFP.

CFIR constructs assessed

The CFIR development team recommends that constructs ‘be evaluated strategically, in the context of the study or evaluation, to determine those that will be most fruitful to study’( Reference Damschroder, Aron and Keith 26 ). We selected seven CFIR constructs of focus for the present study (see Table 2 for constructs and their domains), based on those which we hypothesized would be most relevant to implementing the FL-BFCCI. ‘Relative priority’ was chosen, understanding that centres have many requirements for licensing and regulation, and expecting that this optional designation would likely be relatively low on their priority lists for this reason. We wanted to understand how the ‘complexity’ of the designation process and requirements factored into their decisions about becoming designated. ‘Costs’ of implementing new initiatives can be prohibitive, so we were interested in knowing the costs centres had incurred or anticipated incurring related to seeking designation. Acknowledging that childcare centres are businesses, we expected that administrators’ perceptions of ‘consumer needs and resources’ (e.g. extent to which there were breast-feeding families at the centre) would also be important for their decision making, and would be closely related to ‘perceived tension for change’ (the extent to which there are forces that would motivate the organization to implement something new). We considered assessing other constructs as well (primarily ‘adaptability’; ‘peer – or competitive – pressure’ in the marketplace; and ‘compatibility’, or fit of the designation with their centre), but we deemed these as less likely to be critical and were concerned that assessing too many constructs would make the interviews prohibitively long( 35 ).

Table 2 Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) constructs and interview items used to assess the fit and implementation of the initiative guided by CFIRFootnote *

* These items were specifically designed for this purpose. The interview guide was more extensive; some information about CFIR may have resulted from other interview questions. Constructs listed in the order they appear in text.

† Inner Setting includes structural, political and cultural contexts through which the implementation process will proceed( Reference Damschroder, Aron and Keith 26 ).

‡ Intervention Characteristics include the many complex, multifaceted and interacting components of a given intervention( Reference Damschroder, Aron and Keith 26 ).

§ Outer Setting includes the economic, political and social context within which an organization resides( Reference Damschroder, Aron and Keith 26 ).

Data analysis

Structural codes were applied based on CFIR-related questions in the interview guide (Table 2). If representative quotes were found in separate sections of the transcripts, we also applied those codes. Inductive codes were generated by two authors (V.S. and O.F.). A codebook was created, pilot tested, revised for clarity and relevance of the codes and their definitions, then finalized. The same two authors coded ten transcripts to consensus and one coder (V.S.) coded the remaining transcripts. Applied thematic analysis( Reference Guest, MacQueen and Namey 36 ) was employed using the ‘cluster analysis’ function in the qualitative data analysis software NVivo version 11 to determine possible relationships between the codes. Trustworthiness was obtained by sharing results with interviewers to assess the fit between our interpretations and their perceptions based on the interview experience (credibility), deriving findings from the data and presenting multiple administrator quotes (confirmability), and developing a codebook and keeping an audit trail throughout analysis( Reference Lincoln and Guba 37 , Reference Creswell 38 ).

Results

Participant and childcare centre characteristics

Of the twenty-eight participants (Table 1), all were female; many were non-Hispanic White (60·7 %); all had at least 6 years (range: 6–45 years) of childcare experience and 1 year (range: 1–42 years) as an administrator. Mean age was 50 (sd 9·83) years (range: 27–69 years). The twenty-eight represented centres served a range of low- to higher-income families, with 63 % of centres associated with the USDA-CCFP (Table 1). None of the administrators reported having a written breast-feeding policy.

Current perceptions

Prior to reviewing the FL-BFCCI handout, no administrator knew about the FL-BFCCI. After reading the handout, administrators discussed their perceptions.

Relative priority

Administrators were asked how they would prioritize receiving FL-BFCCI designation, relative to other demands. Only a few (n 6) thought designation should be their highest priority or be sought immediately. Jessica said it would be her:

‘Number one ’cause … I want to work mostly with my babies and see ’em grow and thrive.’

Others (n 4), like Kary, thought implementing the FL-BFCCI would be equally important as other things they do:

‘We will … incorporate it into our programme – just like any other rules and regs we have through DCF [Department of Children and Families].’

Few administrators (n 4), like Libby, thought the FL-BFCCI would fall somewhere in the middle of their priority list:

‘Half-way. Because there’s a lot of things to do in day-to-day functioning.’

Only two administrators expressed that being designated would be a low priority:

‘It wouldn’t be a priority with me … not that I’m not – OK with breast-feeding, I’m just not sure what that would [do] – yeah, in the real world.’ (Faith)

One administrator clearly valued input from her clients regarding the importance of becoming designated:

‘I guess we would probably have to have a survey from our families and see what the need is.’ (Selena)

Another believed that safety was the most pressing concern for her client families:

‘But if your staff are no good, it doesn’t matter whether you’re a breast-feeding environment or not. They want to know that they’re leaving their child with someone who’s going to do right and be safe with their child, because that is more important than saying, “Yes, you could come in and breast-feed”.’ (Isabella)

Complexity

When asked about level of difficulty of obtaining designation, many (n 23) thought implementing the BFCCI requirements would not be complex or few additional resources would be required. After reading the FL-BFCCI handout, Patricia stated:

‘We do everything that it is, so it probably wouldn’t be difficult at all.’

Regarding complexity, need for additional resources – especially for privacy – was a prominent theme, as reflected by Isabella:

‘No, I don’t think it would be [difficult]. I think it’s just designating an area in every classroom. In your infant rooms, you should have rocking chairs in them anyways. So, having a parent turn around for privacy is – you have a wall … I don’t see that being a problem at all.’

While future implementation was not expected to be complex and securing privacy was perceived as easy, other implementation challenges were mentioned, such as requiring multiple stakeholders to be on board, obtaining buy-in from staff members, owners and corporate offices, as well as accommodating parents’ schedules. Helen reflected these concerns:

‘It shouldn’t be difficult at all. … The parent’s schedule and how their children eat – I would say that might be the most difficult thing, because who wants their baby to be screaming and hollering for a formula when the parent don’t want to break till twelve o’clock.’

It is interesting to note Helen’s perception of the breast-fed baby as ‘screaming’ for ‘formula’. This observation suggests a deeper level of complexity of implementing the FL-BFCCI than what administrators explicitly acknowledged: the need to address perceptions of formula as the ‘normal’ or ‘default’ feeding choice.

Cost

Regarding perceived costs of becoming designated, administrators spoke about their existing structures/resources (another CFIR construct within Inner Setting)( Reference Damschroder, Aron and Keith 26 ), training costs and the number of infants under their care. Angela did not think there would be additional costs because:

‘We have a chair … we have a refrigerator room.’

Sophie was concerned about required training costs because:

‘Generally the teachers … have to pay [for] their own continuing education.’

Provided no more substantial structural changes (such as additional rooms or changes to the layout of the building) were required, administrators perceived limited additional costs. However, space was a concern for administrators like Lisa:

‘The classroom that we do have … is not that big. It’s big enough for the four babies in the cribs … if we add … another chair for the mom to come in … it’s kind of like a little box.’

Consumer needs and resources

Regarding the need for designation, some administrators (n 15), like Ruth, explicitly stated need:

‘I think there’s a need out there … a lot of parents are hesitant about putting their babies in childcare this young because they’re breast-feeding. Not everybody will allow the breast milk – you know – to be stored here [at a childcare centre].’

However, others (n 4) stated no expressed need from the community for the designation but noted the need might change if they had more breast-fed infants. For example, Isabella said:

‘I have no breast-feeding parents. I think – [if] we had nine parents who were breast-feeding and one that was on formula, it’s important. … But if you have none…’

She explained that even if they had all structures in place, it would not ensure the mothers breast-feed at her centre:

‘I had one mom who – she’s a working mom. And I used to tell her…, “Please come down here on lunchtime and feed, ’cause she [baby] wants that.” And she would not do it. … She was, like, every hour for her was a dollar. So, I totally understood that. So, the room is set up that if she wanted to do that, already she absolutely can.’

In this case, Isabella encouraged one mother to come and breast-feed but did not acknowledge that there may be a climate at the centre that would covertly stigmatize breast-feeding mothers (i.e. asking mothers to turn their chairs facing the wall while breast-feeding on-site; see above).

Structural characteristics

Administrators were asked to identify what about their organization (e.g. building, set-up, staff size) is well suited for becoming breast-feeding friendly. Over half (n 15) mentioned staff and available resources. Some administrators (n 17), like Lisa, thought everything about their centre was breast-feeding friendly:

‘Everything. I mean, we’ve got … staff, and plenty of space, and, you know, everything that a breast-feeding mom would need.’

However, space was noted as a critical barrier among those who said their centre was not well suited (n 4). For example, Hina said:

‘Uh, that’s the only problem I think I probably would have – is the private area – because my centre is not closed, it’s opened. I don’t have walls. Everything is just open, except for the one infant room and this one office.’

Similarly, Jasmine said:

‘The baby room is small; it only holds eight babies. ... And the rocking chair is right here… if the mothers want to do it, then let her do it. Even if she had to take the baby and go to the car [due to limited space at the centre].’

As with Isabella (above), Jasmine and others may initiate creative attempts to support breast-feeding mothers while confronting space limitations, yet they may not realize how suggesting mothers should breast-feed outside the centre could be interpreted as ‘breast-feeding is not welcome’.

Organizational incentives and rewards

Administrators were asked if staff would require any tangible incentives or statements of recognition to implement the initiative. Most administrators (n 19) thought incentives would not be required, because as Lily said:

‘To be honest ... we do it all already.’

Some (n 7) said incentives were not a requirement but may be helpful in motivating staff implementation efforts:

‘Oh, those little thumbs-ups… and big… thank-yous… add up to everything. … [N]o matter how old we are, we enjoy rewards.’ (Patricia)

Tension for change

Administrators were asked how making the changes required by the BFCCI would help them meet the needs of mothers. Administrators did not express any concerns about present practices at their centre needing change. Some (n 2) explained their centre did not have any – or had only a few – breast-fed infants. Thus, they perceived no real need or benefit of being designated. Other administrators (n 4) did not think mothers were seeking a breast-feeding-friendly designation upon enrolment. One administrator, Faith, was quite reluctant to seek designation; she was sceptical about how the designation would make any positive difference:

‘Why do we need a policy? I mean, why do we need somebody else to come in and say we’re a friendly site when we know we are? … [W]ell, I don’t think there’s a problem with that [being designated]. I think there’s a problem with somebody coming in and telling me … what I need to do to be a – friendly breast – you know, see what I’m saying? But – and again, I don’t want to alienate them – the parents that aren’t breast-feeding.’

It is noteworthy that Faith mentioned concerns about the parents who are not breast-feeding: the normative group in her centre. She was not alone in expressing concerns for this group and resisting the initiative’s efforts to normalize breast-feeding, although it is not clear if these administrators were concerned about protecting other parents or themselves from discomfort. For administrators like Faith, pressure from parents or from licensing and regulation entities may be required for them to seek designation.

Overall, while there was at least a moderate level of support for the initiative and some interest in designation, administrators did not seem convinced that their consumers (i.e. parents) perceive a need for their centre to support breast-feeding mothers or to be designated as breast-feeding friendly. Given the many demands on childcare centre staff, if administrators perceive no tension for change and no relative advantages of adopting (v. not adopting) the designation, it is unlikely that many will invest time and resources to the effort. However, some may be willing to seek designation if they perceive their centre as ‘already doing it’.

Discussion

In the current study, we explored Florida childcare administrators’ perceptions of breast-feeding-friendly childcare centre designation. We found administrators were unaware of the FL-BFCCI and did not perceive the need for their centres to pursue the designation. However, most did not think it would be hard to become designated, should they choose to do so. Those who anticipated major costs were concerned with structural or space issues, as well as staff training.

Administrators were not familiar with the initiative before the interview. Information about the initiative has been available on the websites of Florida’s Breastfeeding Coalition and the FDOH CCFP, the two organizations that administer the FL-BFCCI( 24 ). Efforts to promote the initiative have largely been focused on centres enrolled in the CCFP, which represent approximately 50 % of Florida childcare centres. At least annually, Florida CCFP participants are reminded of the Breastfeeding Friendly Childcare Designation (BFCCD) initiative in a newsletter post. Entities within specific counties and regions throughout the state may engage in more intensive promotion of BFCCD, but prior to the present study, none did so in the region studied here. Given lack of exposure to this initiative prior to the interview, it is possible administrators did not fully understand the reasons for the initiative and the benefits of being designated. This may explain why some administrators did not yet understand the spirit behind it. For example, Jasmine expressed concerns about having the space for breast-feeding mothers to nurse, and suggested mothers could ‘go to the car’ if they wanted to breast-feed while at the centre. While possibly well-intentioned, sending mothers to their car would not truly be breast-feeding friendly. Her perception of what it means to become breast-feeding friendly would likely change if she completed the requisite training.

If continuing education credits were provided for FL-BFCCI training, more administrators and staff might be aware of the FL-BFCCI and able to embody the spirit of the initiative as well as achieve the designation. Anecdotally, in Pinellas County, FL, offering free continuing education credits appears to be attracting administrators and staff to in-person FL-BFCCI trainings. These trainings were designed after the present study was conducted, and provide education on the FL-BFCCI, the normalcy of feeding infants human milk, and proper handling and storage of human milk. Centre administrators who have attended these trainings have expressed desire to seek breast-feeding-friendly designation. As more peer organizations begin seeking designation, a perceived competitive edge (i.e. ‘cosmopolitanism’ in the CFIR) may develop, encouraging others to perceive a need and seek designation. Additionally, as more administrators seek designation, ideas for overcoming structural barriers might begin to circulate. In fact, peer support for administrators could be critical to the programme’s success.

The peer-reviewed literature reveals little of breast-feeding-friendly childcare initiatives throughout the USA. Our preliminary investigations suggest only eleven states have such initiatives. Moreover, those eleven states have varying levels of funding and activities to promote breast-feeding-friendly childcare( Reference Roig-Romero, Schafer and Barr 39 ). Several additional states provide training or materials to help childcare centres support breast-feeding( 23 ). In addition to those and the USDA Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP), we are aware of only one existing childcare-based nutrition programme that incorporates breast-feeding: the Nutrition and Physical Activity Self-Assessment for Child Care (NAP-SACC) programme( Reference Ammerman, Ward and Benjamin 40 – Reference Drummond, Staten and Sanford 43 ), developed jointly by researchers at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the North Carolina Division of Public Health to support childcare centres in promoting healthy children. Given findings of the present study and the lack of data on breast-feeding-friendly initiatives, we argue that to meet the 2011 call of the Surgeon General( 13 ) we need a more robust national effort. While state-specific efforts are likely to make an impact, national support for breast-feeding-friendly childcare could reduce inefficiencies and generate momentum to fuel a more rapid response to the Surgeon General’s call. Some national policy efforts are already in place. For example, the USDA-CACFP will mandate reimbursing centres for food that breast-fed babies would otherwise have consumed, to incentivize support for breast-feeding in childcare centres( 44 ). However, not all centres are affiliated with the CACFP. Moreover, without additional knowledge and support, centres that attempt to be breast-feeding friendly may still inadvertently communicate anti-breast-feeding attitudes; what is needed is a cultural shift.

Other initiatives to change the culture and practice of care for mothers and babies may be useful in identifying strategies for instigating that cultural shift. For example, 1·8 % of US infants were born in BFHI hospitals in 2007( 45 ). Currently, 22·12 % of all US infants are born in BFHI hospitals( 46 ) – exceeding the Healthy People 2020 goal of 8·1 %( 47 ). Although the BFHI is not without controversy( Reference Bass, Gartley and Kleinman 48 ), major change has transpired. This change was likely the result of numerous new metrics and regulatory changes requiring new organizational behaviour. Among these is the metric for recommended lactation care practices at birth facilities in Healthy People 2020, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s biennial Maternity Practices in Infant Nutrition and Care (mPINC) survey, and new human milk feeding reporting requirements of the Joint Commission, which accredits thousands of US hospitals( Reference Perrine, Galuska and Dohack 49 ). Funding from both government and the non-profit sectors to provide technical assistance to hospitals seeking BFHI designation has accompanied the new metrics and regulatory changes( 50 – Reference Feldman-Winter, Ustianov and Anastasio 53 ). If there were national standards for breast-feeding-friendly childcare designation, state- or centre-level metrics, and national resources to support the effort (e.g. handouts, videos, technical assistance), individual states could determine the best ways to implement the programme – similar to the way individual hospitals have found their own paths to Baby Friendly status. Undoubtedly, such cultural and institutional changes will take time( 54 ).

Building on previous qualitative work conducted in Malaysia( Reference Suan, Ayob and Rodzali 55 ), Australia and the USA( Reference Cameron, Javanparast and Labbok 56 ) to understand childcare workers’ breast-feeding support experiences, the present study has implications for policy, regulation and childcare practice, as well as for future implementation research. Childcare workers have the potential to be key public health practitioners but addressing implementation barriers may be critical. The present study shows how the CFIR can be used prospectively for public health promotion. By structuring the interview questions around specific CFIR constructs, we identified potential key implementation challenges (e.g. limited tension for change, critical costs, low perceived concordance with consumer needs). Moreover, in comparing the perceived challenges of implementing the FL-BFCCI with those experienced in an analogous public health effort (i.e. BFHI), we identified potential strategies that may be successful.

Limitations

Study findings are subject to social desirability, convenience sampling, low study participation and non-response bias. Also, we were unable to follow up with administrators to determine how perceptions of the FL-BFCCI may have changed after they had time to process their new knowledge of the initiative and/or obtain additional information. Thus, findings may not be generalizable to administrators who are already informed about the initiative, or to administrators in other settings. We gathered perceptions of administrators ‘in their own words’. Yet this approach does make it difficult to compare perceptions across administrators. Finally, we focused on only seven of thirty-nine CFIR constructs; studies that address additional CFIR constructs possibly relevant to breast-feeding would help to advance the literature and may illuminate additional implementation barriers and facilitators. Nevertheless, findings from the study provide a valuable opportunity to understand potential implementation challenges of BFCCI and identify possible solutions.

Conclusion

We explored childcare administrators’ perceptions of potentially implementing the FL-BFCCI, guided by CFIR constructs. Results highlight that variations in perceived relative priority and costs, lack of fit with perceived consumer needs and low tension for change may limit the success of BFCCI in the current childcare landscape. We believe national policy efforts are needed to change the breast-feeding culture in childcare centres. Lessons learned from BFHI implementation suggest that with a comprehensive policy approach, including regulation, national metrics and technical assistance, a substantial cultural shift is possible and could dramatically increase mothers’ access to breast-feeding-friendly childcare.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank the childcare centres and staff members in the Tampa Bay area for their time and participation in the study. They also thank Rachel Logan, Preeti Vadlamani, Emily Rizzo, Adebukola Sangobowale, Carly Truett, Cheralynn Corsack, Tiffany Graske, Tabassum Tasnim, Laketa Entzminger and Hanh Van Tran for their contribution in data collection and validation of transcripts. Special acknowledgements go to Esther March Singleton from Florida Breastfeeding Coalition, Krista Schoen from FDOH, the FL-BCCFI and Florida Breastfeeding Coalition for their willingness to share information during the study. Financial support: This work was supported by the University of South Florida College of Public Health Individual Investigator Awards. The University of South Florida College of Public Health had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: S.L.M. was the principal investigator involved in all aspects from study design to writing the manuscript. V.S. assisted in study planning and was involved in recruitment, analysis of data and writing the manuscript. E.J.S., A.L.-J., M.M.W., T.L. and R.M.R.-R. assisted in interpretation of study findings and writing the manuscript. D.T. assisted in instrument development, data collection and writing the manuscript. O.F. assisted with data analysis and writing the manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving human subjects were approved by the University of South Florida Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.