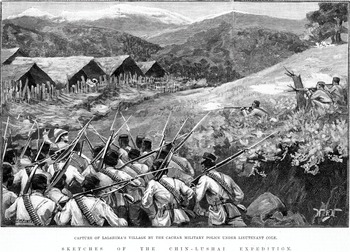

A tribal settlement comes into view in Figure 1.1. Bayonets clatter. An officer signals. Rifle fire erupts, echoing down the valley as defensive stockades splinter. This is a political annexation in progress, and agents of the British Raj – sepoys under the command of an officer called Lieutenant Cole – dominate the scene.

But what if we shift our standpoint? Peering through the palisades towards the troops, concepts like ‘political annexation’ begin to break down. To the upland people within the stockades, this was the ‘time of foreign invasion’ (vailenlai), an Indigenous periodization that itself merits attention. The state’s occupation of these hills did not benignly preface later decades of cross-cultural contact and transformation. Instead, the vailenlai was a violent and complex process in its own right, deeply disruptive to upland lives, with outcomes shaped by local inhabitants in profound but newly constrained ways.

To understand this process, we need to begin even earlier in the hills. A trickle of colonial trade goods crept into the mountains from distant plains and ports, hinting at the existence of the remote Raj somewhere beyond the northern, western, and eastern frontiers of the highlands. People in this region did not originally encounter the official representatives of an imperial state. They saw competing – and often erratically violent – foreign chiefs who needed to be understood and reckoned with. This was, most of all, an era of both exceptional and everyday violence. Invaders unleashed disorienting panic, rumours, forced-labour regimes, disease, and turmoil across the hills and into the routine of highland lives.

Today, modern narratives of the colonial past in Mizoram occasionally internalize the old tropes of imperial improvement by using the operative verb ‘awp’ to refer to the colonial era, evoking a maternal hen incubating her immature eggs: ‘sap in min awplai, or “the time when white men/sahibs ruled over us”’.Footnote 1 The melancholy pasts uncovered in this chapter, however, leave little room for nostalgia or triumphalism.

1.1 ‘Coming into View’Footnote 2

Highland populations encountered the vai only through a dark lens. In outlying riverside bazaars, uplanders and lowlanders had long exchanged chemical compounds: polymers of natural rubber, and crystals of salt and of sulphur.Footnote 3 But in a time of invasion, information about the invaders’ identities and intentions was hard to come by – a situation that must have been particularly alarming given the newcomers’ access to superior firearms, their red uniforms (a colour associated with both status and spiritual power in the hills), their ability to control elephants, and their apparent proclivity for heads and souls.Footnote 4

There was very little to go on except hearsay. Surveying often one-sided documentary evidence, historians have long recognized the difficulty in reconstructing these sorts of Indigenous pasts. But a lack of solid evidence on highland perceptions of these earliest encounters places historians in a very similar position to highlanders engaged in the chaos and panic of discovering the British Raj: we too can only hazard our best guesses.Footnote 5

Deep in zo ram heartlands, the first signs of the vai often came in the form of strange material goods – little fragments of foreign worlds sometimes gleaned by uplanders from debris left behind in the invaders’ abandoned camps or looted from the bodies of the invaders themselves. In 1888, for example, some highlanders from Rangamati in the Chittagong Hill Tracts carried a small, silvery implement eastward across what would become the Lushai Hills District. We know that the item travelled some 400 or 500 kilometres, stopped in multiple villages, and had at least three different owners over seven years. In length if not in heft, the object resembled a thimkual – the brass hairpins worn by men – except it was fashioned out of a white metal and featured a longer shaft, additional prongs and the strange, etched shapes ‘JFS’.Footnote 6 This item was eventually discovered and confiscated by a British political officer in Burma’s Chin Hills in 1895 and sent back to the officials in Lungleh, the nascent headquarters of the South Lushai Hills District.Footnote 7 Such materials – in this case a fork marked with the initials of Lieutenant John F. Stewart, the British official killed by uplanders near Rangamati in 1888 – would have been the first puzzling evidences of the newcomers that many people encountered.

A trickle of foreign goods soon became a surge. Figures 1.2 and 1.3 depict the vai fording a stream and moving cargo. A vast retinue of labourers carry their material goods – a bizarre scene to migratory peoples accustomed to travelling light and acquiring only essential goods. As an observer noted in the 1870s, uplanders on the move generally ‘brought nothing but arms and enough rice for the journey; a fresh joint of bamboo at each new camping-ground serving every purpose[, from] water-jug [to] cooking-pot’.Footnote 8 By contrast, a single Welsh missionary arriving in the North Lushai Hills headquarters of Aijal in 1897 required twenty bullock carts for his luggage and arranged for the ‘coolie’ porterage of at least fifteen additional loads.Footnote 9 Later, when the Welsh doctor Peter Fraser required twelve local people, seven mules, and four ponies to carry his belongings, highlanders joked that the imported goods would last more than a lifetime.Footnote 10

Figure 1.2 ‘How the officers travel in Lushailand’, 1896.

Highland populations’ awe at these goods – their wonder at British material sophistication – is a standard colonial narrative of expansion into the hills.Footnote 11 But, far from overawed, uplanders immediately set about scavenging, adopting, trading for, and repurposing foreign items to Indigenous purposes to make everyday life easier. Discarded cans of condensed milk as well as ink and vinegar bottles became storage and drinking cups that were more durable than their customary bamboo joints.Footnote 12 When a fledgling government dispensary in Aijal began giving out bottled medicines free of charge, people availed themselves of the offer but emptied the suspect contents of the prized bottles.Footnote 13

Migratory highlanders – who had good use for sturdy containers – gave hospitality to touring European missionaries in return for boxes and cans. Others acquired and refashioned metal tins into bases for their smoking pipes or flattened Europeans’ discarded kerosene oil tins to plug gaps in thatched roofs or safely contain cooking fires.Footnote 14 The gold and green labels from glass bottles of pickles and brass sardine tins made life visually richer, acting as colourful hair accessories akin to the more typical iridescent wings of the tlengtle beetle (Chrysochroa vittata). Newspapers transformed into ‘a large fan or hood’ to make headgear more impressive.Footnote 15 Besides hot commodities, the new goods became hot topics. The first sermons of Christian missionaries in the region were often interrupted by queries on topics that resourceful listeners clearly thought were more pressing, like ‘how glass bottles were made’.Footnote 16

Uplanders often valued imported materials in ways manufacturers never intended. Umbrellas were sometimes broken down into constituent parts because the metal spines made great head-massagers.Footnote 17 With little use for fences, hunters acquired fencing wire (and, later, the discarded metal type from the first printing presses in Aijal, depicted in Figure 1.4) to hammer into makeshift bullets for their flintlock guns.Footnote 18 Gurkha troops congratulated themselves on their guile in trading copper coins to gullible locals in return for whole rupees (as legal tender, the coins were hardly worth a sixth of a rupee). But locals were taking advantage of gullible Gurkhas, too; attaching more value to aesthetics (the copper coins looked better in necklaces) and practicality (the copper coins could be pounded into better bullets), highlanders traded inferior rupees for superior copper coins.Footnote 19 For upland hunters in particular, the homemade, lighter copper bullets flew further and faster without any increase in precious gunpowder, increasing both range and damage to animal prey.Footnote 20

Trade was just one route among many into expanding, often unpredictable or improvised everyday relationships with the newcomers. Highlanders learned to play tug-of-war against sepoys (and even emerged victorious).Footnote 21 They laughed when officers cracked their knuckles.Footnote 22 In far-flung villages, local populations mixed with the Gurkha soldiers on initial tax-assessment tours, together ‘singing songs round a fire, with laughing and applause’.Footnote 23

Genuine curiosity often fuelled interactions.Footnote 24 In 1904, a man called Lalhrima from the village of Seshong interrogated a visiting superintendent with probing questions: how many hnam (clans) made up the foreigners? How expansive was the ocean? How populous was London? How could people live in boats for ‘days if the sea was salt?’Footnote 25

People most often greeted touring officials hospitably with cups of rice beer.Footnote 26 In the 1870s, an officer’s sketches helped warm interactions with interested bystanders: ‘it pleased them so much that one went away and returned with the skulls of a deer and a pig, and a live hen, all of which he requested me to draw, which I did; and the lookers on pointed out … even to some discolorations on the skulls, which I indicated by a little shading’.Footnote 27 These sorts of quotidian encounters clustered around the small colonial outposts and markets – the ‘spaces of encounter’ that began springing up throughout the hills.Footnote 28

For all the originality of their toys, games, artillery, songs, and drawings, the newcomers must have seemed naïve about the basics of life. When Captain John Shakespear’s wife was ill during an 1895 tour, the chief Mompunga and his wife were ‘much concerned’ with the newcomers’ complete lack of knowledge about how to heal her. ‘[S]everal times [they] have desired to perform sacrifices to ensure her recovery’, records Shakespear in his tour diary.Footnote 29

The foreign chiefs knew equally little about public health. The colonial archives abound with highlanders baffled at being hauled before colonial officials for participating in the communal killing of dawithiam (in colonial parlance, ‘wizards’ or ‘sorcerers’).Footnote 30 In 1898, Frederick Charles Halliday ordered fifty male villagers into Lungleh to labour as punishment for the killing of a family of dangerous dawithiam. He records how the ‘offenders’ ‘simply could not understand why we made any objection to their action’.Footnote 31 The chief Kapleyha [Kaphleia] (who appears in Figure 1.5) ‘was sorry that we should be annoyed by what he and all his tribe regarded as a rightful act, but evidently put our disapproval down to the utter madness of the strange white men’.Footnote 32

Highland populations assessing newcomers’ attempts at establishing themselves in the hills often saw strangeness and vulnerability. The corrugated tin roofs that colonial officials insisted local men and Santal coolies carry for days up to colonial building projects acted as parasails, tearing off in the heavy monsoon winds. After one gusty night in November 1897, every colonial structure in the southern headquarters of Lungleh had to be reroofed.Footnote 33 The newcomers were perpetually repairing their telegraph lines, which were sometimes blown down for ninety kilometres at a stretch. Cows imported from the plains became emaciated and produced no milk (while highlanders were gobsmacked that anyone would drink it in the first place).Footnote 34 Personal libraries carried up into the hills by oxcart and coolie had to be sunned during the rainy season, lest they rot away.Footnote 35

British troops were often equally helpless. Whole forces became lost in the dense bamboo forests and were only rescued by upland ‘bushcraft’, the intimacy with which locals knew, mentally mapped, and navigated an incredibly dense environment and complex landscape.Footnote 36 When Robert B. McCabe and John Shakespear’s forces could not locate each other one morning in 1892, McCabe set up his heliograph – a signal device that flashed out codes written in sunlight through its mirror and shutter (Figure 1.6). He also dispatched local uplanders as messengers into the forest at random. In the end, the most modern of remote, wireless communication technologies proved no match for the uplanders’ speed of travel or the bandwidth of village chatter: ‘I received an answer the same evening, the messengers having done 30 miles across the hills in ten hours.’Footnote 37 While colonial agents often disparaged Indigenous knowledge, expertise and ways of thinking about the world, the empire’s presence in the hills was only made possible because of local know-how, labour, produce, and hospitality, whether given freely or otherwise.Footnote 38

At the same time, the perceived foreignness and loneliness of the hills compounded the newcomers’ vulnerability.Footnote 39 Between 1891 and 1894, some seventy-one Gurkhas from the military police absconded from the district home to Nepal.Footnote 40 Others killed themselves.Footnote 41

Despite, or perhaps as a result of, the difficulties faced by state agents, the first superintendents were keen to send local chiefs and their assistants (upa) to the metropolises of Chittagong and Calcutta to ‘exercise a beneficial effect on the Lushai tribes’ by demonstrating the sheer extent of colonial rule as well as its supposed civility and modernity.Footnote 42 In the hills, Indigenous political power was dispersed in complex webs that linked individual chiefs (lal) and clans (hnam) via relationships of kinship, debt, reciprocity, marriage, and friendship.

In such a world, the newcomers’ claims to abstract, overarching power made little sense. As he oversaw British stockades being drilled into mountaintops across the land, engineer G. H. Loch remarked that ‘[o]ne of the things most difficult to make a Lushai understand is that the Political Officers at Fort White, Falam, Haka, Lungleh, and Aijal all serve the same Government’.Footnote 43 To the south, uplanders perceived military assistance, extended from a column from Burma to one in the Lushai Hills, as merely a temporary chiefly alliance. The following year, people theorized, ‘the Fort White chiefs might fall to fighting among themselves’.Footnote 44

In all of this, highland populations insisted on their own codes of interpersonal honour, seeking reciprocity with the newcomers in familiar political idioms of chiefly relationship and alliance. Elephant tusks were presented to British superintendents. Incoming British officers were expected to honour agreements made by their predecessors.Footnote 45

British superintendents did gradually learn to initiate oaths of peace by sharing in the symbolic killing of animal wealth or the eating of hill buffalo liver.Footnote 46 In the early 1890s, colonial festivals in Lungleh designed to ingratiate the newcomers to upland leaders were modelled after traditional forms that colonial officers simply termed ‘big drink[s]’.Footnote 47 In 1892, an officer called Lalmantu (R. B. McCabe, known as the ‘Chief Hunter’ for his military attacks on village chieftains) invited six prominent chiefs from across the region to such a gathering to try to clear up the administrative confusion. Attempting to find some conceptual middle ground, he decided to portray the Europeans as ‘brothers’ that ‘represented one authority only, that of the Queen Empress [Kumpinu, or the (East India) ‘Company Mother’]’.Footnote 48

Other colonial officers had different methods. Putara, the Old Man (G. H. Loch), attempted to transcend the political common senses in the region by removing people from it; he hoped that elders Sonthang and Thabaie, sent to Calcutta at government expense, might ‘understand that it is the same Government at Calcutta and the other places they have seen’ as it was in Aijal and Lungleh. Highlanders sent travelling to distant lands would understand the full territorial extent of British pre-eminence, or so they thought.Footnote 49

The travels rarely produced their desired results. Indeed, far from being overawed by the spectacle of foreign lands and the grandeur of colonial modernity, upland people confidently articulated critiques of each and acted in ways no one expected. When W. C. Plowden’s upland travellers returned from Calcutta to Lungleh in 1895, Shakespear recorded disillusionment: ‘I am sorry to say they seem rather dissatisfied, saying “there was lots to be seen, but we were not allowed to see it; there was lots to buy, but we were not allowed to buy it”.’Footnote 50 One chief, Lalluova, is recorded as saying upon his return, ‘[S]uch thousands of people, and among them all not one that knew me: it is better here’.Footnote 51 When one Liana was taken to visit Calcutta and Darjeeling with G. H. Loch, ‘he was shown the grand panorama of the Eternal snows on the [Kanchenjunga] range. All he said was “Oh, I have seen that sort of thing before in my own country”.’Footnote 52

In 1872, T. H. Lewin’s group of eighteen chiefs and their companions likewise surprised their host by displaying ‘impassivity’ and ‘stolidity’, rather than the expected wonderment, at the steamboat journey from Chittagong to Calcutta.Footnote 53 The chiefs did give Lewin the pleasure (‘[o]nce, and once only’) of appearing ‘roused to enthusiasm’ and even ‘fairly frightened’ by the Raj’s technological prowess; they were rocketed for ‘a mile at full speed on a fiery, snorting locomotive engine’ specially lent to Lewin ‘for the purpose’ by an officer of the East India Railway.Footnote 54 But to focus on Lewin’s glee, which was based on the idea of two opposed worlds – one tribal, one civilized – misses the bigger picture. Throughout the late nineteenth century, ‘civilized’ Europeans the world over continued to struggle with the novelty and speed of railway journeys just like the Mizo travellers; lowlanders and uplanders alike feared derailment and disaster. Trains were dreadful for what they were – fire-powered monstrous juggernauts hurtling along a track – irrespective of who was riding inside.Footnote 55

Back on solid ground and continuing their tour, the chiefs refused to meet with the viceroy. Instead, they chose to meet the lieutenant governor of Bengal, presenting him with elephant tusks and homemade cloths (‘as to an equal’) and leveraging gifts in return – a reciprocity that they would have recognized as standard chiefly diplomacy. Lewin later recorded his sadness that ‘the magnificence of the City of Palaces [Calcutta] did not apparently impress them … On the whole, the balance of their minds inclined in favour of their own hill-tops’.Footnote 56

Far from dumbfounded and passive spectators, the chiefs remained selective and perceptive. These ‘savage headhunters’ camped on the city’s famed Maidan, surveyed the imperial capital, and articulated that which ailed it.Footnote 57 As Calcutta faced out-of-control urbanization and swarms of bugs that made malaria endemic, the chiefs expressed a longing for their homes, ‘where the ceaseless jostling of strange men troubled them not’ and ‘where there were no mosquitoes’.Footnote 58

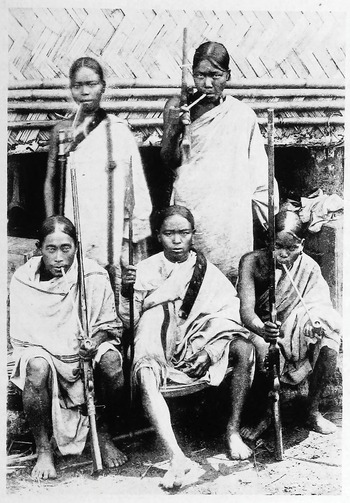

The thoughtful confidence and poise exhibited by the armed chiefs and their retainers is evident in photographs taken in Calcutta (see Figure 1.7).Footnote 59 Given the chiefs’ selective leveraging of gifts and diplomacy to those they gauged as equals, their journey from upland Fort Lungleh to lowland Fort William, usually seen as the performance of British paternalism, can be reinterpreted to represent something else: the strategic extension of Mizo political and spiritual power into the very heart of the Indian empire.Footnote 60

1.2 Everyday Violence in the HillsFootnote 61

When the colonial agents Old Eyes, the Chief Hunter, the Old Man, and others first climbed into the heart of the Lushai Hills, they styled themselves adventurers, explorers, and white princes in remote, exotic, and unmapped lands. ‘As explorers we were always penetrating the unknown – did I not myself lead my merry men to the summit of Blue Mountain [Phawngpui], the first white man ever to set foot there-on?’Footnote 62 wrote Military Police Officer Frederick Charles Halliday in 1898. In fact, part of the draw of frontier posts like Halliday’s was the promise of reduced imperial oversight, or what one early administrator’s wife understated as the District’s ‘somewhat special form of administration’.Footnote 63 Decisions looked after by whole departments in other regions in India were, in the Lushai Hills, centralized in the person of the superintendent, who was ‘judge and magistrate’ as well as ‘head of education, forests, public works, [and] police, including the Military police’.Footnote 64 Government documents referred to superintendentships in the District as ‘almost independent position[s]’ and officials in Bengal worried (often with evidence in hand) that these ‘out-of-the-way’ posts encouraged incumbents towards rashness rather than discipline.Footnote 65

These self-styled pioneers arrived in the lands of a diverse range of people whom they lumped together as ‘artless savage tribes’ or worse.Footnote 66 Coupled with the looseness of administrative oversight, this rhetoric worked to underwrite a distinctively heavy-handed form of administration in the nascent Lushai Hills District, where superintendents quickly earned reputations as individuals of erratic violence. The case of Charles S. Murray, the first superintendent of the South Lushai Hills District, is an extreme one indicative of a general trend. Murray had built his reputation crushing tribal rebellions across eastern India, first in western Bengal and Bihar in 1880 and then, five years later, in Darjeeling. In 1890, he marched further eastwards, this time in aid of the Raj’s occupation of the lands of the Mizo people and the recovery of Lieutenant Stewart’s head. One of the few extant visual depictions of Murray – whom uplanders came to call Marliana – can be found in an 1890 issue of The Illustrated London News in which Murray is portrayed killing a hill buffalo in symbolic allegiance with the highland chief Mompunga (Figure 1.8). Within a year, however, the Government of India removed Superintendent Murray for building a new reputation for violence – this time as a serial rapist of women in villages like Khawhri.

Figure 1.8 Mompunga and Murray.

In 1891, Panjiham Tipperah, son of Chandra Singh, one of Murray’s interpreters, made the following sworn statement about a riot in Khawhri under the Fanai village chief Zakapa (alternatively spelled Jacapa or Jakopa). On a cold day in January of 1890, not long after the annual harvest, Murray had stopped at Khawhri to demand kuli labourers for the government’s roadwork projects. He also demanded sex for himself and an assistant.

On the arrival of Mr. Murray to Jacopa’s village, Jacopa met the Saheb with welcome. Mr. Murray told me to get two girls for himself and the Chota Saheb (Mr. Taylor). I said, where shall I get them from[?] Mr Murray said, tell the Chief to get them. I did so. Then I and Vaitlaia and Jacopa searched for these girls, and could not get them any. Then we went to Mr. Murray and told him and he said ‘Why cannot you get them; go and make a “Banda bust” [an arrangement]’. Afterward we persuaded two girls to come but when I told them that they would sleep with the Saheb, they said ‘No, we won’t’ and run [sic] away. Then we three went to Saheb again. We said we will catch them if you like. Jacopa agreed to this. Then Murray Saheb said ‘No do not catch them, the Sepoy [soldiers] will see, but if you cannot bring me two women, I will have the wives of Jacopa and Pajika’. Jacopa was present and Mr. Murray said it in Lushai [language], and at once Jacopa’s family began to leave the village.Footnote 67

Despite being grossly outgunned, the remaining villagers of Khawhri attacked Murray’s forces. Two sepoys and an assistant were killed during the fighting. Murray himself escaped into the forest as his forces burned most of Khawhri’s houses and grain reserves.Footnote 68 Twenty days later, Shakespear’s column of nearly 150 Gurkhas and Frontier Policemen returned to Khawhri to finish the job.Footnote 69 Twenty-four highlanders were killed as the settlement and its grain stores were all burned to ashes – an atrocity seen as depraved even by the British officer who felt compelled to commit it: ‘I knew all along that Murray must have been much to blame and it hurt me badly having to deal so harshly with Jacopa’, recalled Shakespear (who would replace Murray as superintendent). ‘But at that time one could not be lenient in cases of our parties being attacked.’Footnote 70

When colonial forces finally captured Zakapa five years later and tied him to a post (Figure 1.9), the chief was unrepentant.

Figure 1.9 ‘Jacopa on the evening of his capture’. John Shakespear, in ‘Lushai reminiscences’,

Why should I [have] not [attacked Murray?] [H]e asked for two young women and when they fled he demanded my wife. I refused so he went to burn our rice. Seeing he was going to destroy that on which we depended for life, I could do no other than shoot him.

Officials whitewashed Murray’s misconduct. Only the testimonies of Panjiham Tipperah and Dara preserve the details of the case in the archival record. Colonial reports and writings instead refer obliquely to a ‘disaster’, an ‘affair’, or an ‘unfortunate incident’Footnote 71 – a case of ‘those who commit the murders write the reports’.Footnote 72 Contemporary military writings leave out Murray’s demands for sexual corvée, blaming the twice-burning of Khawhri on Zakapa’s withholding of kuli labourers.Footnote 73 Following a hushed investigation, Murray was quietly removed from the District and sent westwards to the Chittagong Hill Tracts to take up the more easily supervised post of assistant commissioner.Footnote 74 When Zakapa was finally captured in 1896, the chief was sent to Chittagong, in Murray’s footsteps, to serve a three-month sentence.

Murray’s terror outlived his deportation from the Lushai Hills. In 1903, rumours reached the ears of local Baptist Missionary Society missionaries James H. Lorrain and Frederick W. Savidge about an eleven-year-old boy with skin like theirs. The mother, Thangtei, was summoned to bring her child, Challiana, who was immediately seized. Thangtei had hidden her boy, conceived during Thangtei’s assault by Murray, as long as she could. Under missionary Savidge’s bungalow roof and tutelage, and with financial support from Murray in England, the stolen boy was groomed into a translator, church pastor, and medical assistant (Figure 1.10). Early mission registers recorded converts’ ‘clans’ (Fanai, Chongthu, and so forth), and Challiana’s clan was listed as ‘Sâp’.Footnote 75

Murray was not the only colonial agent to earn a reputation for unleashing everyday physical, sexual, and psychological violence.Footnote 76 McCabe seized women and children and sent them under military guard to Aijal as hostages, refusing their husbands and fathers who came to beg for their return.Footnote 77 Other officers recorded their ‘pleasure’ at burning entire villages.Footnote 78

Colonial forces demanded firewood, vegetables, rice, goats, and chickens from villages, sometimes pressing a single settlement to yield upwards of 200,000 calories for a single force’s meal.Footnote 79 Male forced labourers conscripted from village populations were sometimes ‘severely assaulted’ by their overseeing officers; one man forced to work on the Serchhip road had his ‘head cut open’ by a sepoy.Footnote 80

These sepoys were not only liabilities for a village’s male population; in 1894, two Mizo men walked some 100 kilometres to Aijal to complain that a Kuki colonial soldier had – in a fashion reminiscent of C. S. Murray – attempted to rape one of their village women when delivering a government ‘notice for coolies’.Footnote 81 Any village refusing a labour demand might find itself hosting sepoys with orders to ‘live free on the village’ until the workforce was supplied.Footnote 82

Though light on the ground in terms of actual manpower, colonial officials in this era clearly oversaw a ‘government by terror’.Footnote 83 In 1897, the Whipping Act was extended into the hills, granting the superintendent power to sentence people, including juveniles and female tea-plantation workers, to punishments of flogging.Footnote 84 Standing orders were later issued to curb the practice of government workers assaulting uplanders with ‘light canes etc.’.Footnote 85

It was in this context of quotidian terror that a young Mizo man (tlangval) approached touring officer John Shakespear for some tobacco. A nearby chief warned the youngster in the Mizo language: ‘Be quiet, these foreign chiefs when angry [are] like tigers.’ The chief’s choice of metaphor provides a glimpse into how uplanders at the time perceived the newcomers not only as chiefs but also as dangerous beasts. Shakespear overheard the remark and responded by punching the young man in the face – proving the chief’s point.Footnote 86

1.3 Kuli

Officials in Bengal began to see the highlanders as potential coolies because of costs and distance; government coolies had to be transported from far-flung camps to Calcutta, from Calcutta to Chittagong, and from Chittagong up into the Lushai Hills. There were real prospects for sickness and exhaustion on the journey.Footnote 87 With labour from neighbouring Khasi Hills also deemed too expensive, officials concluded that ‘if roads are ever to be made about this country, they will have to be made with local labour’.Footnote 88

Labour demands were immediate, significant, and varied (Figure 1.11). Men were forced to build houses for the families of soldiers and military police in distant colonial centres. Others were tasked with carrying hundreds of sheets of corrugated iron across mountain ranges, rebuilding shops when colonial agents ordered bazaars moved, and clearing the jungle around the colonial outposts of Lungleh, Fort Tregear, and Demagiri.Footnote 89

Roadwork was the most widespread and loathsome task of all. Tens of thousands of male villagers were put to work on coerced roadwork gangs supervised by soldiers. They cut footpaths alongside rivers, trails through forests, and roads across mountains, linking the colonial headquarters of Lungleh to local and other colonial settlements.Footnote 90 Kulis even had to carry their own food to work sites or found their meagre pay reduced.Footnote 91 Though the state technically only demanded male labourers, women and even children also shouldered heavy loads. The wives and daughters of forced labourers from Lalthangvunga’s village, for instance, had to help carrying touring officials’ goods on a particularly difficult stretch of road that required clambering ‘over boulders and tree trunks’.Footnote 92

Climate compounded the burden. In recent years, disaster-studies scholarship has emphasized the human-made character of so-called ‘natural’ cataclysms: cyclones, earthquakes, and monsoon floods are environmental processes, but their devastation is exacerbated when humans build in their regular paths.Footnote 93 In the Lushai Hills, monsoon seasons and attendant cyclones regularly dumped around 2.2 metres of rain per year in the north and a colossal 3.7 metres in the south.Footnote 94 In a District distinguished by its landslide-prone gradients (over 70 per cent of the land area, well over 2 million hectares, slopes at angles steeper than 33 degrees),Footnote 95 the infrastructural decisions of colonial officials literally paved the way towards a vicious cycle of coerced road repair and landslide excavation (a government road is depicted under construction in Figure 1.12).

People in the rainier south bore an even greater burden. Only one month into the rainy season of 1896, the brand-new trace road cut at Sailengret was deemed unfit for transport use: ‘The trace goes along cliff sides a sheer drop of some two or three hundred feet and the loose soil is constantly giving.’Footnote 96 Overworked villagers remembered the unusually stormy year of 1895 as minpui kum – the year of landslides.Footnote 97 Larger disasters made things even worse. The Shillong earthquake in June 1897 rattled its way southwards across the Lushai Hills, pulling down tonnes of dirt ‘along the Government roads and caus[ing] much inconvenience, necessitating constant road repair work’.Footnote 98

Government thoroughfares were not benign ‘public works’ or evidence of either technocratic ‘progress’ or transportation’s ‘improvement’. They were environmentally inappropriate in the hills, impossible to maintain without mass coerced labour regimes that victimized vulnerable populations. In contrast, Mizo footpaths, some following trails carved by elephants through the jungle, were narrow, less labour-intensive to both create and maintain. In other words, vernacular pathways were sensitive to the environmental processes that defined zo ram, the highlands, as a region.Footnote 99

Kuli demands seemed limitless.Footnote 100 Ten days’ labour per man each year, not inclusive of travel time, was the labour requirement cited internally by government officers.Footnote 101 In practice, actual demands were far more variable. No maximum was fixed ‘as circumstances may arise in which a large quantity of labour is needed’, and Mizo ignorance of any government temperance on the labour question was seen as favourable.Footnote 102

At the end of the workday, upland men employed on forced roadgangs scoffed at the four-anna coins that they were presented.Footnote 103 They gave the cash away to children in plain view of overseeing officers, ‘implying that it was beneath their dignity to retain’.Footnote 104 The coinage was already an attempt to short-circuit highlanders’ indifference; it had been introduced after forced labourers decided to use their paper-money earnings to roll cigarettes.Footnote 105

When a rumour circulated that the maximum load per coolie was ‘twenty seers’ (roughly 18.7 kilograms), Mizos began insisting on the weight cap, evidence that they were learning foreign units of measurement to defend themselves. Colonial officials determined to break this load-limit ‘superstition’ gave kulis from Lalhrima’s village each a thirty-seer load (roughly 28 kilograms).Footnote 106 Upland bodies bent and broke under the newcomers’ rule.

1.4 Exceptional Violence in the Hills

Highland bodies had long borne colonialism’s many traumas. Local perceptions of limitless forced labour need to be viewed against the backdrop of larger-scale hostilities and violence. British invasions into zo ram heartlands in the early 1890s had been timed to coincide with the end of the annual rice harvests, so that the troops could force resting harvesters into porterage duties and eat freshly harvested rice rather than carry supplies.Footnote 107 As Shakespear gloated in 1892, ‘It is pleasant to see the villagers really working hard at cleaning their own dhan [unhusked rice] for our consumption.’Footnote 108

That year, McCabe used famine conditions as a combat tool. The upcountry crops that year had been an ‘utter failure’ thanks to drought conditions and the purposeful interruption of planting cycles by state violence. McCabe saw people’s hunger as a ‘blessing’ and imported rice that he offered only in return for hard labour.Footnote 109 He wrote:

I cannot reiterate too strongly how firmly I am convinced that burning a Lushai village and then withdrawing is no punishment. We must hunt the enemy down from camp to camp and jhum to jhum, destroy their crops and granaries, and force them by want and privation to accede to our terms. … Exposure and starvation are our strongest allies, and with their assistance I believe that the Lushais will be very shortly craving for peace.Footnote 110

Villagers in the eastern regions under the banner of Lalbura resisted the newcomers with force, though they had little to eat other than jungle produce ‘and what little rice they were able to beg or borrow from their more fortunate neighbours in the west or south’.Footnote 111 Inhabitants in the north, near Changsil, were reduced to collecting sticks from the jungle and exchanging these with local sepoys for something to eat.Footnote 112

The appropriation and destruction of village grain reserves were highly gendered forms of state violence because they targeted ordinary women’s work. Women were primarily responsible for growing, transporting, and husking rice (see Figure 1.13). In the hills, women of status were also valued for their rice wealth, which was sometimes significant enough to be commemorated on memorial stones.Footnote 113 State agents hypothesized that grain destruction, and thereby the disruption of agricultural cycles and food security, was the most effective way to ‘get rid of a troublesome community’ or to drive highlanders towards settling under ‘loyal Chiefs’.Footnote 114 Assuming that all wealth was male wealth, colonial armies set about cutting off the food supplies of resistant men by destroying what they failed to recognize was women’s work and wealth.Footnote 115

In their pursuit of peace via military supremacy in the early 1890s, British forces in the already impoverished Chin and Mara villages south of South Vanlaiphai committed atrocities that were ‘regret[ted]’ in reports as ‘harsh measures [that] had to be taken here as the people lied so terribly that it was impossible to either get information or guns’.Footnote 116 Local officials, however, celebrated McCabe’s reign of terror as having ‘good effects’ despite being ‘very severe’.Footnote 117 In 1894, when the village of Ramri fled instead of offering food and coolies to a touring colonial force, the village was completely burned. Shakespear preemptively excused his behaviour to officials in Shillong, who were beginning to take notice even in spite of the notorious administrative freedom-of-hand in the Lushai Hills: ‘The punishment of this village may seem severe, but it is necessary to show these people that we wont [sic] be trifled with.’Footnote 118 On one hand, severe violence was tolerated and even occasionally praised; on the other, it was frequently described as excessive and in need of justification.

Highlanders improvised. Colonial forces came across abandoned settlements pockmarked with excavated pits, evidence of a fleeing village carrying away stores of rice secreted away from the state.Footnote 119 Underground chambers, encircled with split bamboo, consisted of carefully engineered sedimentary layers designed to preserve their precious contents. A top layer of soil roughly a foot deep capped a layer of bamboo and palm leaves that hid any assortment of wealth beneath: corn, millet, nets, looms, brass pots, embossed bronze bowls, alloy gongs, or rice paddy.Footnote 120

When colonial forces learned to dig up pits of concealed rice within villages or to look for grain salted away in distant jhum huts, some villages began locating their hidden bunkers even further afield.Footnote 121 In 1892, sepoys dug up great pits of rice in an eastern Lushai Hills village, burning what officials estimated to be tens of thousands of kilograms of rice – a colossal destruction of agricultural exertion and rice wealth.Footnote 122

Fear loomed everywhere. Every colonial tour through the mountains brought with it the possibility of forced labour and bloodshed – of ‘violence over the land’.Footnote 123 In the mid-1890s, it was becoming more and more difficult for colonial agents to find anyone willing to work as an interpreter: ‘They do not want us to interpret, they want to kill us.’Footnote 124 Upland postcarriers (dakwalla, after the Hindi) refused to carry the post without an escort through the mountain trails.Footnote 125

Figure 1.14 A political officer (possibly Robert B. McCabe) surrounded by field officers of the North Lushai Column at Fort Aijal, c. 1892.

Childhood was transformed as broken parents ceased teaching traditional games during the upheaval.Footnote 126 Village children fled into the jungle at the first sight of white people arriving in their village, with cries of, ‘Ka pu, khawngaih takin engmah min ti suh’ (‘Sir, please do not harm us’). Later, Christian missionaries found out that these children had thought they would be kidnapped; the white man was to be feared.Footnote 127

The newcomers were feared most of all for delivering ‘violence in astonishing new ways’.Footnote 128 Many hill leaders were deported far over the horizon, some to distant lands unknown to Mizos. Many were never heard from again, like the chief Lianphunga, whose fellow villagers appear armed and defiant in Figure 1.15 prior to his capture.Footnote 129 Highland people who crossed the ‘Inner Line’, an invisible colonial boundary in the forest near Cachar, to climb and tap rubber trees were shot down ‘like birds’ by British forces.Footnote 130

Figure 1.15 Armed men at Lianphunga’s village in 1890, shortly before British forces burnt it down in their quest to capture the elusive chief. Adam Scott Reid, Chin-Lushai Land, with Maps and Illustrations (Calcutta: Thacker, Spink & Co., 1893), p. 251.

Violence shattered families and childhoods; when a four-year-old Mizo child lost sight of his parents amid a gun battle near Kholel, he was immediately ‘adopted’ by a Cachari officer from Assam.Footnote 131 In other cases, entire villages were forced to construct shelters for touring soldiers, at least once upon the charred remains of a village burned by the same soldiers two years prior.Footnote 132 These experiences were not exceptional to the early Mizo experience of the Raj but constitutive of it. It is no coincidence that elders described the arrival of the newcomers from the Indian lowlands as a great ‘boiling over’, capturing the scalding of upland lives as violence flooded across the hills.Footnote 133

The concept of the ‘information panic’ has proven useful to understand the British Raj’s difficulties, failures, and insecurities about acquiring and interpreting information about colonized societies, their intentions, and movements.Footnote 134 The concept is equally applicable in the reverse direction; colonized peoples panicked about a dearth of knowledge about the state and its motives, especially in times of extreme violence.Footnote 135

High in the Himalayan foothills, sightlines of violence were maximized. The mountaintops where people built their villages provided long sightlines and uniquely distant horizons. Outside of the smoky jhuming season, the topography itself compounded the terror that undergirded rumour and panic; the rising smoke of villages being burnt communicated panic across great distances.Footnote 136

Ordinary individuals relied on information delivered orally across difficult terrain, on inter-village messengers and emissaries, as well as on rumour and community gossip (khual thuthang) in order to be bengvar (‘quick-eared’ or informed).Footnote 137 Amid the rising smoke, conflict, rumour, and panic, it was difficult for highland populations to be quick-eared. It was impossible to penetrate, let alone comprehend, the newcomers’ information systems.Footnote 138 Early on, the newcomers’ written words delivered via post (dak) and telegraph lines were technologies far more easily sabotaged than infiltrated and understood.

Excesses of state violence and uncertainty gave rise to fresh speculation about the foreigners’ intentions and capabilities. Many chiefs refused an official’s invitation to Lungleh’s lavish New Year celebrations in 1892 for fear that the summons was a ploy to assemble and punish them – or worse.Footnote 139 Chief Lalbura offered a dreadful twin prophecy: the powerful foreigners would one day imprison the upland kulis and hold them for the ransom of all local guns.Footnote 140

Superintendents noticed how villagers ‘appear[ed] extremely suspicious of [their] intentions … ’.Footnote 141 The chief Tholing, from near Serkawr (modern Saikao), refused to believe that colonial authorities in both the Lushai Hills and the Chittagong Hill Tracts meant him no harm despite repeated assurances. In 1897, he arrived with an entourage of seventy men to speak to R. H. Greenstreet, the superintendent of the Arakan Hill Tracts, and requested permission to move his village away from colonial authorities.Footnote 142 Likewise, the ‘morbidly nervous’ chief Kairuma refused to meet with any sahibs or their agents.

[Kairuma] quoted the deaths of so many leading chiefs since our occupation of the hills, including chiefs such as Sailienpui and Lienkhunga, who died in their own houses, as proofs of our malevolence and powers of magic, and in justification of his refusal to see the interpreter [Sib Charan, sent from Aijal to speak the chief].Footnote 143

Kairuma’s fears were soon confirmed. In retaliation for his refusal, two groups of sepoys arrived to kill off his village’s animal wealth (fifty pigs and a mithun) and seize nearly 1,500 kilograms of grain.Footnote 144 The stakes were perceived to be so high that highland people issued stern warnings across the land: anyone colluding with the oppressive vai would be killed when the occupiers were eventually forced out.Footnote 145

1.5 Disease

Far from being experts on treating disease, the newcomers seemed to cause it. In 1884, Alexander Mackenzie noted that locals closely associated white people with cholera in the hills.Footnote 146 According to a report in Calcutta’s newspaper The Pioneer, Mizos called cholera ‘vay-dam-lo’ (vai damlohna, ‘a foreign illness’).Footnote 147 When, in 1861, a group of uplanders carried the lethal ‘crowd disease’ up into the hills after a raid (likely into what the Raj knew as the Chittagong Hill Tracts), it ‘spread the greatest terror among them, many of them … blowing out their brains on the first appearance of the disease showing itself’.Footnote 148 In 1895, a cohort of Santal coolies working for the government carried cholera with them into Demagiri and Lungleh, resulting in ninety cases treated and twenty-nine deaths.Footnote 149

Highland populations visiting the newcomers’ bazaars paid with their lives. In 1860, the Kassalong bazaar (in the Chittagong Hill Tracts) was said to be the source of a smallpox outbreak among upland villages.Footnote 150 After three highlanders contracted cholera in 1894 at the Demagiri bazaar, officials temporarily barred anyone else from visiting it.Footnote 151 People visiting the colonial headquarters of Aijal to procure imported wares likewise carried cholera back to Mompunga’s village, where fifteen people died.Footnote 152 Chiefs and puithiams – the guardians of public wellbeing – were confronted with powerful foreign illnesses that they had little experience healing.

The historical reactions of highland individuals, like the true extent of the destruction caused by the diseases, are largely lost to us. Modern epidemiologists note that epidemics of cholera target adults and the most productive members of society: mothers, hunters, traders, and cultivators. The symptoms associated with cholera must have been alarming: muscles cramped, children fell into comas, heartbeats became irregular. Those infected released diarrheal fluids, projecting the cholera bacterium into water supplies and propagating the microbe.Footnote 153 In a world where someone hostile always caused sicknesses, upland populations were under attack by truly powerful external forces. Unknown to highlanders, the diseases took their toll against the wider backdrop of a British India in which civilian mortality was also soaring.Footnote 154

The earliest colonial jails in the hills – little more than single rooms, like the roughly 220-square-foot ‘lockup’ built in Demagiri in 1899 – were additional sites of death and panic, especially in the upland world where only animals, never humans, were caged.Footnote 155 In 1895, one Dokama died from sickness in the Lungleh jail, unable to access highland remedies.Footnote 156 His was a common plight. A year prior, the intermediary Lalaram requested that colonial officials allow him to return home following his mother’s death. He hoped to assist her spirits (of which humans had two) in leaving the world of the living. But officials refused the request because two high-profile prisoners at Chittagong Jail (the ill Ropuiliani and her son) required Lalaram as an interpreter. Events like these were all-round crises of healing. Lalaram could not release his dead mother to the spirit world; Ropuiliani, sick in lockup, could not heal herself in the usual ways.Footnote 157

Still other prisoners survived jail to find that their families had died in the interim. Thangula, a colonial resister from the northern Lushai Hills, was deported in 1891 to Hazaribagh Jail in Chotanagpur. His family often inquired anxiously after his health.Footnote 158 In 1893, a message dictated by Thangula in Mizo was dispatched to the Lushai Hills and read to his family, who were then told that they would not see Thangula for at least five more years.Footnote 159 When the chief finally returned to Aijal in 1895, he had no desire to return to any village: he ‘was destitute, and … his wife and three children had died in his absence’.Footnote 160

Sometimes prisoners escaped. In 1897, a man of the Fanai clan escaped from a guardroom at Lungleh. In iron leg shackles, he hobbled into the forest for twenty-one kilometres before he was able to smash his shackles with river rock. When he was finally captured and handcuffed, the man was allowed to sleep in his mother’s house one final time, but he fled during the night, breaking free from the handcuffs and enjoying freedom for ‘some days’. Three Fanai chiefs harboured their fellow clansman, clandestinely ferrying him between their villages. The fugitive eventually gave himself up and was jailed again in Lungleh.Footnote 161

In the words of one official, the story ‘shows how determined these men can be and what hardships they can face’.Footnote 162 It also shows the scale of colonial occupation. Across the hills, uplanders wished it would end. Farmers planted banana trees and wishfully prophesied that the occupiers would leave before the fruit was ready.Footnote 163 Local chiefs immediately took advantage of ‘the difficulty that they thought [the foreigners] were in’ and urged all villagers to abscond from kuli work when Fort Tregear accidentally burned in 1892. Three years later, smug stories buzzed from village to village heralding a group of chiefs who had successfully withheld kulis from the state and thereby revealed its failing strength.Footnote 164

When these rumours reached Aijal, they actually served to reinforce the severity of kuli demands. Superintendent Shakespear believed that softening demands for labour would only further encourage buoyant gossip about the government’s waning powers.Footnote 165 Shakespear was periodically forced to confront the chatter head-on. He called a durbar (council) at the beginning of 1893, bringing together more than twenty chiefs and clan representatives, many of whom were in conflict with one another as well as with the new administration.Footnote 166 His speech was adamant.

I hear that you are always saying among yourselves – ‘Soon the foreigners will leave our country and return to their own.’ That is fools’ talk and the word of a liar. We shall never leave these hills. … There is one more word to be said. We did not come here for pleasure: we did not want your land: but you have obliged us to leave our country, which is far better than yours, by your folly in continuing to raid our villages, and now you have got to pay us tribute of a basket of rice per house, and to give us coolies when we want them.Footnote 167

Upland hopes for the collapse of colonial rule were not only rebutted with speeches (and redoubled demands for labour and tribute) but also with architectural responses. Stone-and-brick buildings – the first of their kind in the region – began to dot the landscape around Aijal, partly intended to communicate ‘a look of [the sawrkar’s] permanence and solidity’Footnote 168 to the uplanders (Figures 1.16 and 1.17). To the south, highland visitors to Lungleh wandered through a strange and expanding landscape of colonial structures: a Civil Medical Office, telegraph and post offices, a guard room, prisoners’ cells, a treasury, two army barracks, a godown (or storage building), an office, and the grand houses of the superintendent and his assistant.Footnote 169

Characterizing colonial outposts as mere ‘administrative headquarters’ misses an important phenomenological point. The sight of the stockades of the fort at Champhai, great spikes made of teak and oak; the vista of Aijal’s buildings, some made of rock hewn from the earth; the sounds of army and artillery drills reverberating across the mountainous amphitheatre of Lungleh. Each of these communicated the dreaded permanence of the British to upland witnesses desperate for information.Footnote 170

1.6 Non-Violent Hill Resistance

As the colonial world of uncertainty looked increasingly permanent through the 1890s, upland populations actively engaged in everyday resistance, using the ‘weapons of the weak’.Footnote 171 Hated officers were clandestinely mocked in the vernacular tongue and given nicknames like Bully, Crooked Nose, Old Disagreeable, or The Angry Old Man.Footnote 172 Footdragging was rampant. Forced labourers routinely arrived late and did shoddy work when left unsupervised.Footnote 173 By 1895, officials were exasperated: ‘They cause us much worry by their unpunctuality in obeying our summons, and laziness when they have obeyed it.’Footnote 174

People spurned the government’s demands for tribute rice. Since grain was used to nourish colonial forces, many uplanders inconvenienced the sawrkar by paying cash instead.Footnote 175 Ironically, the government’s meagre cash payments for kuli work supplied locals with a pool of petty cash to fund this minor act of resistance. Others, including twenty-nine villages in 1898, refused to send in any tribute at all.Footnote 176 The chief Kairuma declared, ‘I will give rice etc., When the sahibs come, and I will give coolies to carry their baggage, but I will not give up a single gunlock ever, nor will I send coolies to work on the road or at Aijal, nor will I see the sahibs.’Footnote 177 In 1895, a family of chiefs, together ruling over some 1,465 houses, even refused to supply coolies. The colonial government panicked that the challenge undermined its position in ‘the eyes of every chief in the district’.Footnote 178 Creative strategies of evasion were myriad. When a colonial agent came calling to a village in South Lushai Hills, the man the officer hoped to speak to about the illicit regional gun trade was simply ‘kept [too] drunk’ to talk.Footnote 179

Highland people twisted truth as well. Villages falsified their numbers of livestock, denying meat to hungry sepoys on tour or forcing officers to use their telescopes to spy distant, unreported goats.Footnote 180 Thanruma’s villagers lied to political officers, saying that no paths existed between their village and that of Tlongbuta – a chief who was to be fined twenty-three guns.Footnote 181 Numbers of guns were chronically misreported.Footnote 182 Prospering settlements excused themselves from tribute, reporting instead ‘that the rats have eaten up their crops or that the rain washed the seeds out of the ground’.Footnote 183 By 1900, officers in Aijal dispatched their many orders (parwanas) to chiefs on physical pieces of paper rather than solely via the human tongue, lest chiefs continue to pretend they had never heard the orders.Footnote 184 Even so, chiefs learned to question the written word, claiming that tribute records were in error and that their village owed nothing further.Footnote 185 Others bypassed the government’s nascent land ownership regulations by jhuming the land first and making excuses later.Footnote 186

Villagers insisted that village heads protect their wellbeing or threatened to move. Any chief not protecting his or her inhabitants from house tax and labour demands, the chief Lalbura explained to a colonial official in 1892, was swiftly abandoned.Footnote 187 Villagers also took matters into their own hands. Theft from the newcomers was not only a means of sabotage but also made people rich. Colonial dak runners carrying military police wages were robbed en route.Footnote 188 The army officer Subadar Bikaram even cited evidence that local coolies stole some of the sepoys’ iron cooking pots they were forced to carry.Footnote 189

Colonial agents responded with a brand of ‘divide and rule’ policies. Gun licensing regimes, for example, tried to pit highlander against highlander. In 1896, villagers who reported unlicensed guns were to receive half the fine (usually Rs. 50/- or Rs. 25/- if the firearm was surrendered peacefully).Footnote 190 But these tactics failed. Despite the promise of huge monetary rewards, the scheme drew a mere ten guns that year. The only informer was a man called Bhuju – not a Mizo name.Footnote 191 By contrast, 177 guns were confiscated by force (Figure 1.18).

Highlanders responded to ‘divide and rule’ tactics by further dividing themselves.Footnote 192 Villages in the late 1890s began atomizing on an unprecedented scale. Chiefs splintered off into smaller settlements in an attempt to fly under the radar of the state’s tribute or coolie demands.Footnote 193 These practices were unprecedented acts in a region where, historically, a populous village evidenced a chief’s prestige. In other words, in the fires of colonial occupation, what constituted a good chief was being forged anew; village heads were esteemed not for the number of inhabitants they oversaw but for how well they preserved the communal wellbeing of inhabitants against state rule. ‘Successful’ chiefs were thus leaving colonial agents with an even more ‘amorphous, unstructured population’ that offered few ‘point[s] of entry or leverage’.Footnote 194

Superintendents took notice. With fewer and fewer strong, centralized chiefs from whom the state could demand tribute rice, it was almost impossible to enforce simple orders, let alone to collect and monitor tribute. Far from being lured in by the supposed benefits of colonial ‘civilization’ (land ownership, better access to trade goods, medicine, and so on), villagers were locating themselves away from the newcomers’ outposts. Few chose to live even ‘within a 10-mile radius of the stations’, recorded R. H. Sneyd Hutchinson in 1897. Surveying the increasingly desolate mountaintops surrounding Lungleh, Hutchinson was astonished to find that ‘[p]robably the whole population does not number 400 persons’.Footnote 195

1.7 Violent Hill Resistance

In 1892, John Shakespear called all the Mollienpui chiefs into the colonial headquarters to witness the hanging of the chief, colonial resister, and ‘raider’ Dokola.Footnote 196 For Shakespear, the unprecedented public execution was bound to have good effect; to ‘hang a chief would startle the whole country into the belief that we really did mean what we said’ about the cessation of all intervillage raiding.Footnote 197 But just as the hanging was about to get underway, a telegraph arrived from the commissioner of Assam ordering that Dokola be spared. He was to be deported to the Andaman Islands instead.

The Mollienpui chiefs arrived to good news; Dokola would live. One might read the cheerfulness of their last words to a departing Dokola – spoken clearly in earshot of the superintendent, whose macabre showcase of power had just been cancelled – as an act of passive resistance in itself. Dokola’s assistant said ‘quite cheerfully to Dokola as he was led away – “Go in health; you are going to see the Sahib’s village” to which Dokola replied quite cheerfully – “Yes, I shall see the Sahib’s village.”’Footnote 198

Or perhaps these words were spoken with a wink. Walking through the forest towards the Chittagong Jail with a guard of ten men, Dokola suddenly leapt off the road and rolled down the hillside. A sergeant pursued the fugitive and tackled him, but was stabbed in the back with a knife hidden between the prisoner’s legs. The weapon had apparently been slipped to Dokola, concealed in a meal of rice.Footnote 199

The line between passive resistance and active violence was often blurred in the Lushai Hills. Footdragging delayed the construction of colonial infrastructure; violence reversed it. In the eastern Lushai Hills, locals dismantled government bridges and ladders, piled felled trees on government roads, and perched stones high above thoroughfares, ready to be dropped on British troops.Footnote 200 In the west, an arsonist burnt down two sepoy barracks near the riverine colonial headquarters of Demagiri in 1893.Footnote 201 A year earlier, Mizos killed four cows kept at Aijal and mutilated ten more.Footnote 202 They had never seen these animals before, but they knew they were important to the newcomers. Relations of violence thus extended beyond conventional military operations into everyday acts of desperation and destruction.

British tactics were studied. Literate in the rituals of visits by colonial forces, Lalbura’s village welcomed a battalion led by McCabe with feigned hospitality, leaving the village rice plainly in sight and offering a welcome delegation of rice beer and sugarcane. As usual, the colonial force occupied a portion of the village and settled in. Suddenly, 300 armed men attacked.

We had barely time to complete the message before the Lushais had set fire to the houses all round us, and the flames spread so rapidly that we succeeded with difficulty in removing our baggage and ammunition from the houses and stacking them in a heap in an open square in front of the jolbuk [zawlbuk, a shared training house for young Mizo men] … [T]he heat was so intense that the sepoys’ brass plates, which were laying on the west face of the stack of baggage, were twisted into fantastic shapes.Footnote 203

These moments of violent resistance catalyzed state information panics. Colonial agents frantic for news about the movement of highlanders discussed paying locals for intelligence on the movements of armed groups.Footnote 204 In 1895, frontier guards and tea garden administrators in neighbouring Cachar and Tipperah went on high alert when a rumour swirled that the chief Kairuma was in a position to attack.Footnote 205 Colonial alarm reached a peak in March of 1892 when resisters killed a bullock-herder only 300 yards from the Aijal Fort. As McCabe recorded: ‘The jungle is so dense and the facilities of escape for men like Lushais so easy that it is impossible to outwit the enemy. We cannot distinguish between an Eastern Lushai foe and a Western Lushai ally, and it is quite possible that the men who killed this follower slept in the rest-house at Aijal last night.’Footnote 206 Panics in Aijal translated into astonishing military heavy-handedness on the ground. The following month, squads of police and military men roamed the eastern Lushai Hills for two weeks, ‘destroying all the stores of paddy and other property that they could find’.Footnote 207

In the displacement crises of the 1890s, many villagers decided to uproot their lives to seek sanctuary in lands unmapped by Europeans. Some liquidated their animal wealth, turning chickens and pigs into more transportable cash, and carried whatever else they could manage into the shadows of the jungle.Footnote 208 Some arrived to hidden refuges in the forest – prefabricated emergency shelters built when the need for state evasion was imminent.Footnote 209

Having learned that ‘good’ road access meant supplying tribute and kuli labour, others set off to unfamiliar territory, carrying their possessions on their backs in an effort to put distance between themselves and state infrastructure.Footnote 210 The infamous resister Kairuma located his village equidistant from the four colonial strongholds of Haka, Fort White, Aijal, and Lungleh – as far away from any colonial headquarters as was geographically possible.Footnote 211 Tankama’s villagers, who had lived a two-day march northeast of Aijal, abandoned their homes, gardens, jhum fields, hunting grounds, and buried ancestors for the hope of unadministered lands hundreds of kilometres southeast.Footnote 212

Rumours held that the mountain chains to the northeast – in what the British Raj knew as Manipur – were also safer than the exceedingly violent region called the Lushai Hills District. The colonial archives so very rarely preserve the voice of the ‘invisible displaced’.Footnote 213 This makes a translated plea of an elderly woman Mizo refugee, spoken to a Manipur official in front of a large crowd of fellow migrants in 1900, all the more important.

Most honoured father, we have come into your territory to escape from the worry and annoyance we receive in the Lushai Hills district, the Sahibs and Police are for ever visiting our villages, seizing us as coolies, forcing us to work on the roads, issuing orders, the purport of which we cannot understand, and causing us to live in a state of uncertainty and fear. We know you are a kind father, and we are happy under Manipur Administration, and we pray that you will permit us to remain and pay revenue as the Kukis do.Footnote 214

The British Raj only officially annexed the Lushai Hills District in 1895. Split into two, a ‘North Lushai Hills District’ came under the British Indian province of Assam and a ‘South Lushai Hills District’ under the administration of Bengal. Amalgamated in 1898, the combined district would become geographically the largest in Assam Province, overseen locally by a superintendent in the headquarters of Aijal and regionally by the chief commissioner of Assam at Shillong (Map 1.1).

Map 1.1 ‘The hill country divided between three provinces of British India: Bengal, Assam and Burma’.

By the rains of 1894, most Mizos had learned the danger of not yielding to the newcomers. Even during this crucially busy season of jhum weeding, only two local villages refused to supply forced labourers to repair Fort Tregear. The holdout villages were fined precious guns and forced to supply coolies without pay.Footnote 215 By 1895, colonial officials could boast that ‘[t]his year all the coolies required for the baggage of our tour escorts were obtained from the villages we passed through’.Footnote 216 By 1896, Superintendent John Shakespear proclaimed that the government’s ‘hold over the Lushais is now so good that there is no fear of my orders being disobeyed’.Footnote 217

But resisters did not acquiesce simply because a ‘hold’ became too solid or because they suddenly appreciated the purported benefits of British rule, whether civilization, commerce, or peace. It is more likely that thoroughly ground-down highlanders finally came to resign themselves to conquest, maybe even coming to view the newcomers out of a sentiment that Mizos historically knew as tîm.Footnote 218 Tîm was a very specific kind of fear. A human-eating tiger prowling a nearby jungle conjured tîm. So did a dangerous illness teetering on the edge of mass outbreak. Tîm was what someone vulnerable felt in the face of the random, the predatory, and the powerful. It was a fear provoked by ‘people or things that have power over you and can be neither controlled nor predicted’Footnote 219 – a fear that makes you ‘abstain from doing what one otherwise would do’.Footnote 220 Words like tîm drill down to the core of the colonial experience, where subjugated peoples ‘say yes when they want to say no’.Footnote 221

This specific fear was hard-won. When Shakespear left the hills later that year, he looked back on five miserable years of death, disease, and destruction: ‘I am now leaving this district for good after having held charge of it for five years, ever since it was formed into a district. I do so with regret, for I have had the rough and disagreeable work of subjugating and coercing the people, and I should have been glad if it had been possible for me to remain on to show the Lushais that burning their crops and villages is not the invariable accompaniment of British rule.’Footnote 222

In the Lushai Hills, colonialism provided the infrastructure for the circulation of violence and disease that helped drive upland populations towards its own institutions, particularly the burgeoning schools, medical facilities, and salvation offered by Christian missionaries. It uprooted and scattered vulnerable populations and disrupted the work of healers. In large part, Mizo ‘primitivism’ was just an idea in colonial minds; colonial agents arriving in the hills saw what they expected to see. An overlooked age of warfare also underwrote the destitution, poverty, dislocation, and sickness that colonial agents misrecognized as primitivism but that was, in fact, the results of their own cataclysmic disturbances.Footnote 223 Through claiming to be torchbearers of morality, order, and civilization to India’s ‘savage frontier’, the rapist Charles S. Murray, the hostage-taker Robert B. McCabe, the village-burner John Shakespear, and others like them were the ‘savage frontier’ in many all-too-real ways.Footnote 224

To see old stories anew and to put upland peoples back at the centre of these stories, we must realize that it is our habit of ‘vision, and not what we are viewing, that is limited’.Footnote 225 From an upcountry perspective, it was Chittagong and Calcutta that were the ‘remote’, ‘exotic’, and ‘alien’ settlements (and, according to critical Mizo travellers, deficient ones at that). The Raj ‘came into view’ in an upland centre as much as stateless peoples ever did on an empire’s fringe.

Far from ‘primitives’ overawed by the grandeur of colonial trade goods or the wonders of modernity, Mizos developed creative responses to, and confidently articulated critiques of, their invaders – forces that often found themselves dependent on upland know-how, hospitality, and labour. Far from passive victims, Mizos resisted colonialism and sought out ways to moderate its most profound effects. They adopted new trade goods not only to make their lives easier but also (as with the adoption of colourful synthetic materials for headdresses and jewellery) to make everyday life more beautiful amid the bleakness of fear and conflict.

At the same time, a focus on profound violence and disruption – rather than the celebration of continuity, cross-cultural interaction, and cultural resilience that often characterizes Indigenous-centred studies of colonial encounter – demonstrates that highlanders had to adapt and reinvent themselves within a particular colonial situation and its imposed constraints: brutality, heartache, disease, hunger, and loss. It was into a scattered world-turned-upside-down that two Christian missionaries from the Arthington Aborigines Mission were permitted by the Government of India to visit briefly in 1894, and then again from 1897, to inaugurate the much-heralded process of missionization to which the rest of the book turns. But if there is any room for triumphalism in the history of Mizoram, it is best reserved for those who survived these forgotten years of trauma, dispossession, and oppression.