Within days of their arrival into each of the three cities, the German authorities demanded a representative Jewish Council be established.1 The Judenrat leaders, even from the beginning, were faced with many unenviable tasks, including raising money from the local population as it became increasingly impoverished, signing up Jews to go to forced labor assignments for the Nazis, and passing along the increasingly unwelcome orders of the Germans. Jewish communal leadership during the Nazi occupation had limited power to influence how food was procured and distributed. As time went on, Jewish Councils (Judenräte), with decreasing autonomy, were tasked with carrying out German orders that affected the fate of the Jews. Prewar politics, the Jewish restrictions in a particular city, and the directives and internal politics of the German authorities were all factors in this process.

In all three cities, the Nazis looked to existing Jewish communal organizations or kehillah to supply the leadership of the new councils.2 However, in cities across Poland, many members of the prewar Jewish community leadership had fled. This is not surprising, as intellectuals and leaders of many organizations were targeted for arrest in Polish cities.3 The heads of the prewar kehillah in Łódź, Warsaw, and Kraków, for example, were among those who left.4 In the wake of this leadership vacuum, the Nazi invaders demanded Jewish representational leadership to fill vacant positions. In Warsaw, Adam Czerniaków, a member of the prewar kehillah, became the leader of a new organization to support Jews during the Nazi siege of Warsaw. When the Germans entered, he was selected as head of the Judenrat. In Łódź, the German occupying authorities required that the remaining kehillah members convene in early September 1939 to elect new leadership.5 The election resulted in Avraham Leyzer Plywacki as president and Mordechai Chaim Rumkowski (1877–1944) as vice president. After Plywacki fled the city, Rumkowski was the highest-ranking member of the kehillah left and became its leader. In Kraków, Marek Bieberstein became the new head of the Jewish community.6

Serving in Judenrat leadership was dangerous. In many cities, members of the Judenrat leadership did not make it to the ghetto period. Many were shot or arrested. Others fled when they had the opportunity. Those who continued their leadership into the ghetto period were not out of danger. In all three cities, there were vicious purges of the ghetto leadership. Those who survived purges and did not flee were not always rewarded with favorable assessments. Many would judge these men as inadequate for the task. In his Warsaw diary, Chaim Aron Kaplan was scathing in his assessment of the Judenrat and especially its leader, writing:

The Judenrat is not the same as our traditional Jewish Community Council … the president of the Judenrat and his advisors are musclemen who were put on our backs by strangers. Most of them are nincompoops whom no one knew in normal times. They were never elected, and would not have dared dream of being elected, as Jewish representatives; had they dared they would have been defeated…. Who paid any attention to some unknown engineer, a nincompoop among nincompoops.7

Rumkowski and Bieberstein were similarly derided as unknown or minor leaders by various diarists and survivors, and Rumkowski became a symbol of bad leadership after the war. In the case of Rumkowski and Czerniaków, stories circulated about how they obtained their positions, which suggested in unflattering ways that they sought their positions due to a lust for power. It is unlikely that this is the case.8 But all three had prewar Jewish communal leadership experience and were among the few remaining Jewish communal leaders in their cities when the Germans arrived. Rumkowski and Czerniaków both insisted that they had a responsibility to the Jews of their cities and felt obliged to stay.9 All three faced extremely difficult circumstances that they each handled in different ways.

The Germans did not only monitor and control the Jewish population through the Judenrat. While the Judenrat served as representatives of the German civil authorities, the Schutzstaffel (SS) and German police had their own networks that reported to them on the Jewish community and later on the internal machinations in the ghettos. Sometimes members of the Judenrat reported to both civil authorities and the German police. In other cases, individuals with varying levels of power and protection operated in the ghettos. In Warsaw, a well-known example of this shadow leadership was the so-called Thirteen. Led by Abraham Gancwajch, the organization was charged with combating profiteering in the Warsaw ghetto. In Łódź, Dawid Gertler headed the Sonderabteilung, which reported to the German police, while his deputy Marek Kliger served as an agent to the Gestapo.10 In Kraków, various leadership positions in the Jewish police reported to the German police. Officially, these units were frequently tasked with combating smuggling or monitoring other activities that crossed the ghetto border fences. As a result, these operatives also affected food access in the ghetto. This shadow leadership was generally purged at some point in the ghetto period or as the ghetto came to an end.11

The most significant turning point for the appointed Jewish leadership was the creation of the ghetto. Ghettos evolved from designated residential zones at varying rates, eventually becoming completely closed off from the rest of the city. With the creation and eventual sealing of the ghetto, the Jewish leadership went from representing a community within a city to being responsible for a district and its inhabitants. The closed ghettos, the first of which was the Łódź ghetto in May 1940, became their own cities within a city, with the Jewish leadership greatly expanding to administer the ghetto. Closed ghettos also required the German administration to monitor what entered and exited them, including the incoming food supply. The Łódź ghetto was abruptly sealed, its residents cut off from the rest of the city, while in Warsaw the process was slower. In Kraków, the ghetto was sealed in stages, with Jews able to enter and exit the ghetto as individuals, then groups, and then not at all.12 The creation of ghettos and their eventual sealing made the Jews reliant on the Nazi authorities for access to food. The Jews of Warsaw were aware of conditions in Łódź and were keenly aware of the dangers of a closed ghetto. Diarist Kaplan, writing in Warsaw upon the announcement of its ghetto’s sealing, wrote, “A closed ghetto means death by starvation.”13

Warsaw

The prewar leader of the Warsaw kehillah, Maurycy Mayzel, fled the city when the war broke out.14 Czerniaków, an engineer by profession, had served on the prewar kehillah and was thus appointed on September 22, 1939, by Warsaw mayor Stefan Starzyński to be the new head of the Jewish Civilian Committee of the Capital City of Warsaw (Żydowski Komitet Cywilny Miasta Stołecznego Warszawy). Czerniaków, a Warsaw native, was fluent in German, having lived in Dresden. During the interwar period, Czerniaków had been actively involved in Jewish and Polish politics.

When the Germans entered Warsaw, they quickly established a Judenrat, ordering Czerniaków to create it on October 4, 1939.15 The new council comprised twenty-four members, who were confirmed on October 13, less than two weeks into the German occupation of Warsaw. Many of the original Judenrat members left Poland in the first few months of the occupation.16 Others were removed for reasons ranging from being arrested to not managing their responsibilities. Those who left were replaced by others. In February 1940, the Judenrat had a number of engineers, like Czerniaków himself, including Dr. Rachmil Henryk Gluecksberg, Stanisław Szereszewski, Abram Sztolcman, and Marek Lictenbaum, who would become the second head of the Warsaw ghetto after Czerniaków’s death. Other members included prewar leaders from Agudat Israel: Ber Ajzyk Ekerman, Szylim Ber Jamier, and rabbis Dawid Szpiro and Szymon Sztokhamer. The medical and legal fields were represented by dermatologist Izrael Milejkowski, former judge Edward Eliasz Kobryner, and barristers Bolesław Rosensztat, Bernard Zundelewicz, and Hilary Tempel. A number of factory directors and merchants with experience in major organizations and philanthropy were on the council, including Tadeusz Bart, Bernard Zabludowski, Jakub Berman, Abraham Gepner, and Lazarz Labedz.17 There were also assorted others, including Józef Jaszuński, the director of the vocational training organization ORT (Obshchestvo Remeslenava Truda or the Organisation for Rehabilitation through Training); Chil Rozen; artisan Baruch Wolf Rozenthal; and war veteran Herman Schwartz.18

The Jewish Council had representatives from a spectrum of the Warsaw Jewish community, but it did not fully represent the Jews of the ghetto. The last elections held for the Warsaw kehillah, in 1938, had resulted in 30 percent of the seats going to Bundists, 26 percent to Agudat Israel, and 22 percent to moderate Zionists.19 The Polish government rejected these results and appointed its own board. The Judenrat put together by Czerniaków included a number of individuals who had been on the government-appointed board and a few individuals who were selected to represent the diversity of politics in Warsaw. However, most of those who served on the board were elite and assimilated Jews. One strong piece of evidence that the Warsaw Judenrat did not represent the common ghetto dweller was that Polish, rather than Yiddish, prevailed as the official language of the ghetto (as an accommodation to the Yiddish-speaking masses in the Warsaw ghetto, bureaucrats working for the Judenrat were required to be able to converse in Yiddish to keep their positions).20 Another piece of evidence was the existence of parallel organizations in the ghetto, particularly Jewish socialist organizations, that continued to operate but were not well-represented in the official Jewish leadership.

The Warsaw Jewish community, like those of Łódź and Kraków, suffered in numerous ways. Unlike in other cities, however, we have a bit more insight into the workings of the Jewish communal leadership in Warsaw because Czerniaków, the leader of the Warsaw ghetto, kept a diary of his experiences. He recorded his thoughts on his position, such as:

I now find myself in a post which I did not assume on my own initiative and of which I cannot divest myself. I am not independent and I do only what is possible. Everyone can testify that I work hard, from early in the morning till late at night…. Don’t think that I am driven to doing things because I am frightened. What have I to fear? Death? One dies only once, of this I am always aware, and this we must all remember.21

Czerniaków contended with a great number of issues. Early in the German occupation, the Jewish leadership’s on-hand resources were taken by the Germans. Its bank accounts, like those of all other Jewish communal organizations, were frozen. Despite this situation, the newly formed Judenrat was responsible for the support of the Jewish community, which itself was suffering from frozen bank accounts, constant fines from German authorities, dwindling resources, and an increasing reliance on communal support. Financial difficulties drove the Judenrat to impose taxes on the community and to seek support from charitable organizations, particularly the American Joint Distribution Committee (AJDC). Over time, during the ghetto period, taxes would increase in a vain attempt to compensate for the shrinking tax base.

The early Jewish Council was particularly in need of resources due not only to its assets being frozen but also to the large number of refugees who arrived in Warsaw after its fall to the Germans. Exacerbating the number of refugees arriving in Warsaw was Heinrich Himmler’s October 30, 1939, order to remove Jews from the Warthegau region to the General Government.22 Himmler’s order was eventually canceled, but not before thousands of Jews were sent into the area. Another item that would take a toll on the community budget was the creation of the ghetto.

The ghetto in Warsaw was created slowly. The Germans announced its creation in the city in early November 1939, with Jews being given a deadline of only three days to enter it. This announcement caused panic throughout the Warsaw Jewish community. Diarist Kaplan recorded on November 8, 1939, “The ghetto decree gnaws away at our depressed world. No one had foreseen this catastrophe, even though the conqueror’s treatment of the Jews in Germany was known to us.”23 The decree was eventually forestalled, but the specter of ghetto loomed for Warsaw. The Jews of Warsaw were subjected to increasing restrictions and, by January 1940, were not allowed to change their residence without permission.24 Restrictions on the use of public transportation, automobiles, and other means of transit further hindered Jewish movement. The Germans began to erect wire fences and other measures to delineate the future ghetto area. Eventually, in April 1940, they forced the Jewish Council to provide the labor and funds to erect a wall around the area of the future ghetto. In June 1940, a three-meter-high (ten-foot-tall) wall topped with broken glass was completed, surrounding the 425-acre ghetto area. By August 1940, Jews were required to leave the German district, and Jews newly arrived in the city were compelled to move into the Jewish district.25

Just before the ghetto was closed off, Czerniaków, along with other members of the Judenrat leadership, was taken prisoner and, in the process of being arrested, was badly beaten. In his diary he describes his arrest: “the officer in charge set upon me, hitting me on the head until I fell. At this point, the soldiers started kicking me with their boots. When I tried to stand up they jumped on me and threw me down the stairs. Half a flight down they beat me again.” Czerniaków was released, but it would not be the last time he (or other members of the Warsaw Judenrat, for that matter) would be beaten in his capacity as leader of the Jews of Warsaw.26

Eventually, the Germans, seizing on an outbreak of typhus, sealed the Warsaw ghetto, claiming that a closed ghetto was necessary to prevent the spread of disease.27 This tactic of justifying Jewish separateness from the rest of the population on the claim that Jews were riddled with disease was repeated in the sealing of ghettos throughout Poland. Signs were erected around ghettos cautioning against disease, and propaganda connecting Jews with disease were disseminated.

Emmanuel Ringelblum, writing in his wartime diary, noted on November 19, 1940:

The Saturday the ghetto was introduced (16th of November) was terrible. People in the street didn’t know it was to be a closed ghetto, so it came like a thunderbolt. Details of German, Polish, and Jewish guards stood at every corner searching passersby to decide whether or not they had the right to pass. Jewish women found the markets outside the ghetto closed to them. There was an immediate shortage of bread and produce. There’s been a real orgy of high prices ever since. There are long queues in front of every food store, and everything is being bought up.28

The ghetto comprised 73 streets, 22 entrances to the city of Warsaw, and 61,295 dwellings. At the time that it was closed off, in November 1940, there were approximately 390,000 Jews in the ghetto, which meant a density of 6.4 residents per apartment. The ghetto population continued to increase in the first six months of its existence, peaking at approximately 450,000 in April 1941.29 The population then began to decline again, down to approximately 400,000 in January 1942, when the ghetto was reduced from its original 425 hectares to 300 hectares in size. Thus, a population of the same size that had initially squeezed into the 425 hectares had to fit into 30 percent less space.

The Judenrat of Warsaw transformed as the needs of the Jewish community of Warsaw evolved. Numerous departments, often headed by a Judenrat member, emerged over time. Tasked with running a small city within a city, the bureaucracy of the organization expanded to fulfill many of the roles that had previously been played by the local government. Departments that dealt with ghetto finances, social welfare, care of children including the running of orphanages, health services, labor supply, manufacturing and production in the ghetto, food distribution, the registration of births/marriages/deaths, burials, sanitation, ghetto police, housing, schools, and religious affairs, among others, were formed.

The ghetto and the city remained connected to the extent that in November 1940, fifteen thousand non-Jews held passes into the ghetto to allow them to provide services ranging from water-pipe repair to factory work within the ghetto boundary, and four hundred Jews held passes to enter and exit the ghetto for various reasons.30 The Warsaw ghetto, despite becoming a closed ghetto, would remain relatively porous, enabling smuggling to augment the number of calories entering the ghetto. Smuggling was not without its dangers, however. It would eventually become a capital crime enforced by the Germans. The new ghetto was policed inside by the newly formed Jewish Order Service (Jüdischer Ordnungsdienst). It was established in October 1940 under the command of Józef Szeryński, who before the war was a high-ranking police officer and Catholic convert. His police force answered to both the Judenrat and the Polish and German police.31 Ultimately, with the closing off of the ghetto, it became responsible for order inside the ghetto walls. Overseeing Szeryński on behalf of the Judenrat was Leopold Kupczykier. In December 1940, due to conflicts between the two, Judenrat member Bernard Zundelewicz took over the task of overseeing the Jewish police.

The new police force established that candidates for the Order Service were required to be: “Age, 21–40; education, six classes of secondary school; good health; height, min. 170 centimeters; weight, min. 60 kilograms; completion of military service; unblemished past (no criminal record); references from two persons known in the district,” and stipulated that only those who were Jewish, no converts, were eligible.32 Despite these restrictions, diarist Mary Berg noted that the Warsaw Jewish police had many more applicants than needed, with individuals obtaining the positions in large part due to social networks and bribes.33 In addition to the official police force, which was under the direction of the Judenrat, the organization known as the “Thirteen” (officially the Office to Combat Profiteering and Speculation) took a key role, reporting directly to the German Security Police (Sicherheitspolizei, a.k.a. SiPo).34

Despite the Jewish police forces, German authorities continued to seize property from Jews inside the ghetto. Sometimes it was a surprise attack, such as the one described by Berg in her January 10, 1941, diary entry:

Last night we went through several hours of mortal terror. At about 11:00 p.m. a group of Nazi gendarmes broke into the room where our house committee was holding a meeting. The Nazis searched the men, took away whatever money they found, and then ordered the women to strip, hoping to find concealed diamonds. Our subtenant, Mrs. R., who happened to be there[,] courageously protested, declaring that she would not undress in the presence of men. For this she received a resounding slap on the face and was searched even more harshly than the other women. The women were kept naked for more than two hours while the Nazis put their revolvers to their breasts and private parts and threatened to shoot them all if they did not disgorge dollars or diamonds. The beasts did not leave until 2:00 a.m., carrying a scanty loot of a few watches, some paltry rings, and a small sum of Polish zloty.35

At other times, proclamations were made that let officials into Jewish homes to seize belongings. There was a requirement that Jews hand over furs, and official searches and seizures were conducted to ensure compliance. During fur coat inspections, other valuables were seized from Jewish homes, including “sugar, flour and other provisions.”36 Many impoverished Jews had no means to pay taxes owed from before the outbreak of the war. City officials empowered by the German occupiers went into the ghetto to seize assets in an attempt to collect back taxes. This resulted in many Jews being dispossessed of their last means of survival.37

Łódź

The Jewish Council of Łódź was among the earliest to be formed, predating Reinhard Heydrich’s Schnellbrief of September 21, 1939, which laid out Nazi policy for occupied Poland.38 On September 12, 1939, a few days after the Nazi entry into Łódź, the Jewish community leaders who had not fled the city were convened by the Nazis to select new leadership from among themselves. Jakub Lejb Mincberg, the prewar head of the Łódź kehillah, had fled. His deputy, Plywacki, remained in Łódź and was selected as the new head, with Rumkowski as his deputy.39 The newly constituted Jewish communal leadership became the official liaison between the Jewish community and the Germans. This leadership configuration, however, did not last longer than a month. In the second week of October, Plywacki left Łódź for Warsaw.40

On October 14, 1939, Rumkowski became the head of the Jewish community and the representative of the Jews of Łódź to the Germans.41 The former director of a Jewish orphanage at Helenowek, and a Zionist representative in the Łódź Jewish community, Rumkowski was given broad powers, including power over the entire Jewish community, the ability to tax the community, and control over communal institutions. Additionally, he was authorized to select the members of his council. He selected a group of prominent Jews to serve as members of the Jewish Council, or Bierat, as it was known in Łódź. The Bierat comprised thirty-one men, a significantly higher number than the twenty-four-person maximum laid out in the Schnellbrief. Those nominated by Rumkowski were sent a letter stating:

Pursuant to the order of the Commissioner of the City of Łódź, you are hereby appointed a member of the Council of Elders (Ältestenrat) at the Jewish Community of the City of Łódź. Acceptance of the mandate is compulsory. The first meeting of the Council of Elders, to which you are cordially invited, will be held on Tuesday, the 17th day of this month at 4:30 p.m. in the premises of the Jewish Community of the City of Łódź, 18 Pomorska St.

Those who became members of the new Jewish Council included: Abram Ajzner, Henryk Akawie, commercial court judge Edward Babiacki, Markus Bender, Dr. A. Damm, Samuel Faust (who would eventually serve as the director of the department for social aid), director Artur Frankfurt, factory owner, industrialist, social activist, and philanthropist Pinkus Gerszowski, W. Glass, Stanisław Glatter, Jakub Gutman, Dr. Dawid Lajb Helman, Jakub Hertz, Mieczysław Hertz, Szmul Hochenberg, Ignacy Jaszuński, Jakub Lando, Jakub Leszczyński, Fiszel Lieberman, Leon Mokrski, Chil Majer Pick, Jonas Rozen, Leon Rubin, Dr. Jakub Schlosser, Dawid Stahl, Robert Switgal, Dawid Warszawski (who was eventually made the head of the tailoring department), Dr. Zygmunt Warszawski, Izydor Weinstein, Dawid Windman, and Maks Wyszewiański.43 This new Jewish leadership configuration for Łódź did not last even a month. On November 11, 1939, all but two of the members of the Bierat were arrested and taken to Radogoszcz prison. Those arrested were tortured and, with the exception of a few survivors, murdered.44 The attack on the early Jewish Council coincided with Łódź’s incorporation into the Warthegau region and a period of terror that included the destruction of the city’s synagogues. Rumkowski has been accused by some of having caused the death of members of his Bierat by complaining they did not comply with orders. This does not seem to be the case, however, as Rumkowski went to beg for the release of his fellow Jewish leaders, only to be beaten himself.45

Rumkowski was ordered once again to form a new Jewish Council. His new council was appointed on December 6, 1939, consisting of twenty-one members, including a few who survived the first Bierat.46 Many, unsurprisingly, were averse to taking a position on the second Bierat after learning of the first Bierat’s imprisonment, and many other prominent individuals fled the city. The result was that Rumkowski did not have a strong Jewish Council, unlike the other ghettos. He did, however, put together a group of advisors during the ghetto period that functioned similarly to a Judenrat.

Around this time, the German authorities were secretly planning for the creation of a ghetto in Łódź. The establishment of the ghetto was ordered on December 10, 1939, by Regierungspräsident Friedrich Übelhör, but unlike the Warsaw ghetto, this plan was kept secret.47 The Łódź ghetto was not publicly announced until February 8, 1940, three months after Warsaw’s was announced, but it was the first of the three ghettos to be sealed. Less than a month after the announcement of the ghetto, Jews residing within the ghetto area were no longer allowed to leave, and all those who did not yet live in the ghetto area were ordered to move into it. Jews who did not move into the ghetto by the appointed time were deported.48

The ghetto plans underwent numerous changes from the version originally envisioned by Übelhör, which had included a sealed-off ghetto area as well as barracks for Jewish laborers within the city.49 This latter part of the plan, which entailed having Jewish workers live outside the ghetto walls in Łódź, was short-lived. In the same secret memorandum creating the ghetto, Übelhör ordered that necessary supplies, including food, be provided by the ghetto.

It was at this point that the Judenrat became an important agency for finding space for each of the displaced Jews arriving into the ghetto area from other parts of the city. This became the purview of the housing department. To maintain the new residences, house committees were formed, just as before the sealing of the ghetto, to keep buildings neat and to manage waste removal. The duties of the house committees were soon extended to include collecting money for food rations and distributing the rations.50

Baluty, the neighborhood announced as the location of the ghetto, was the poorest section of the city. It had only recently, during World War I, been incorporated into Łódź. In addition, Stare Miasto, an area that had previously been restricted to Jewish settlement, and Marysin, a suburb that included the Jewish cemetery, were encompassed in the ghetto area. The total ghetto area was approximately four square kilometers (or 400 hectares), surrounded by approximately eleven kilometers of barbed wire.51 The ghetto had a virtually negligible water and sewage system. Only 725 out of 31,962 apartments (2 percent) in the ghetto had running water. Slightly less than half that number, 343 apartments, had both running water and a toilet.52 Most of the apartments consisted of only one room.53 However, a small number (250) of so-called luxury apartments were available that had both a toilet and gas in the kitchen. These units required rent payments of 150 percent of their prewar rent. Everyone else paid 4 percent of their salary toward rent. One family described how their apartment was slowly filled with people: “first we gave the kitchen away to a family, three people, a mother, a boy and a girl. The father died or something. And then we had to give away another room. So, we were left with a room and a half. Of course then all my family moved in with us. My mother’s father and both my grandmothers.”54

Beginning on March 1, 1940, Jews were not permitted to leave the ghetto area without permission, but the move-in process continued through April, during which time barbed wire was put up around the ghetto.55 One particularly brutal incident, known as “Bloody Thursday,” took place on March 6 and 7, 1940: “That night, the Germans broke into the houses of Jews living in Piotrkowska Street and herded them into the ghetto amid rampant violence in which hundreds were killed.”56 After that incident, temporary passes allowing Jews to move about outside the ghetto area were invalidated. By May 1, 1940, the ghetto was sealed. According to calculations of the ghetto’s Department of Vital Statistics, there were 163,177 persons in the ghetto on May 1, 1940, the first day of its existence.57 With the sealing of the Łódź ghetto, more elaborate self-governing structures were needed to keep the ghetto community in order. Rumkowski was charged with responsibility for the ghetto’s order, labor, and food distribution. Over the course of the ghetto period, Rumkowski would employ a veritable army of individuals to distribute food in the ghetto. Prominent men would be put in charge of individual departments and tasks. These same individuals would then be shuffled over to other leadership positions dealing with factory production or other initiatives.58

Like the other ghettos, the Łódź ghetto had a police force that was created to supervise the Jews. The Łódź ghetto police force was set up just before the ghetto’s sealing, with Leon Rosenblatt as its head. The ghetto police force would play a role in combating smuggling – and the lack of smuggling in the ghetto would be a factor in its high rates of starvation.

Unlike the Warsaw and Kraków ghettos, the Łódź ghetto did not have a long period of adjustment or permeability. Łódź was one of the most tightly sealed ghettos of the Nazi period. It was surrounded by barbed wire and had only one main entrance. This is in stark contrast to the Warsaw ghetto, which had many entrances. Passes to enter and exit the ghetto did exist in the first few weeks, but they were soon invalidated. Some Jews in desperation still slipped out of the ghetto. Łódź ghetto survivor Freda M. was interned in the ghetto. She and her sister escaped to the Aryan side to get food from their former apartment. Two German soldiers followed the girls and raped them, before letting the girls go and telling them they were lucky to be able to return to the ghetto alive.59 Others who were caught sneaking across to the Aryan side in the early days were imprisoned. The lack of people moving between the ghetto and the city ultimately had a significant impact on food access inside the ghetto.

Kraków

When the Germans arrived in Kraków they appointed Marek Bieberstein as head of the city’s Jewish Council. Kraków’s was among the earliest of the Jewish Councils to be formed; like the Łódź council, it even predated Reinhard Heydrich’s Schnellbrief of September 21, 1939.60 The city’s first Jewish Council was called the Board of the Jewish Religious Community in Kraków, and its initial leadership was announced on September 17, 1939.61

Officially, the Board of the Jewish Religious Community in Kraków was formed by the order of the prewar vice mayor of Kraków, Stanisław Klimecki, whom the Germans appointed mayor after the prewar mayor, Bolesław Czuchajowski, fled. There are multiple, contradictory stories of how the early Judenrat in Kraków was formed, but it seems clear that the Jewish Council under the leadership of Marek Bieberstein was established on September 12 or 13, 1939, just days after the Germans entered Kraków.62 According to Leon (Leib) Salpeter, who was himself a member of the Kraków Judenrat (although not one of the original members):

No member of [the prewar Jewish communal leadership] remained in Kraków, nevertheless, it was necessary to create a body that would represent the Jews before the Germans. The officiating vice president of Kraków [Stanisław Klimecki] called for several Jews he had known and ordered them to create a temporary directorate of the Jewish community. That’s how the temporary directorate, consisting of the twelve [sic] members with Marek Biberstein as the president, was constituted.63

An alternative version was presented by Aleksander Biberstein, the brother of Marek Bieberstein, who claimed that SS-Oberscharführer Paul Siebert who would eventually head the Kraków gestapo’s unit IVB for Jewish affairs, established the first Judenrat, just days after the Nazis occupied Kraków, by coercing Marek Bieberstein into serving as the head of the council and soliciting others to serve.64 In that scenario, Marek Bieberstein received a written order on September 8, 1939, from Siebert to form a Judenrat that comprised himself and twenty-three others.65 Perhaps the most dramatic version was told by Henryk Zimmerman, who claimed that two SS men burst into Marek Bieberstein’s home on September 8, 1939, and gave him two days to put together a council.66 Several versions place the initial solicitation of Bieberstein on September 8, two days after the Germans entered Kraków. Although the identity of the person who created the council differs across these stories, what remains consistent is the element of compulsion.

The original Board of the Jewish Religious Community in Kraków was headed by chairman (Obmann) Marek Bieberstein, teacher, Zionist, and public activist prior to the war, and deputy chairman Dr. Wilhelm Goldblatt (b. 1879), a widower and lawyer before the war.67 Theodor Dembitzer served as secretary of the council and headed the construction department.68 There were numerous engineers on the Jewish Council, including Bernard Miller (b. July 1, 1879) and Wladislaus Kleinberger, a B’nai B’rith member.69 Ferdynand (Feiwel) Schenker served as head of the taxation department, with Dr. Joachim Steinberg, a prewar industrialist who would eventually head the tax collection department, as his deputy.70 Schenker would later serve as temporary head of the Jewish Council, following Bieberstein’s arrest. Ascher Spira (b. 1875), a jeweler, headed the Sprawy socjalne (Social Affairs).71 Rabbi Schabse Rappaport was another Judenrat member who, like Bieberstein, would not make it to the ghetto period. The deputies were Izydor Gottleib and Samuel Majer.72 The Jewish Council was expanded to include Dawid Frisch, who headed the burial department, Maksmilian Greif (b. 1883), a prewar bank vice president who headed financial matters, and Dr. Maurycy Haber, who, along with Chaim Samuel Herzog, headed sanitation and the health department.73 Bernard Leinkram was in charge of resettlement; Leib (Leon) Salpeter, who survived the war, headed welfare; Rafał Morgenbesser was in charge of organizational matters and general affairs; Dr. Dawid Schlang, along with Dr. Dawid Bulwa, a prewar lawyer and Zionist, was in charge of education; Aron Schmur and Joachim Goldflus (b. September 4, 1897, in Kraków) were in the upholstery business and were in charge of food.74 A number of individuals were also mentioned as Jewish Council leaders either by Aleksander Bieberstein or by Salpeter, who survived the war, but not by both. These additional individuals include Dr. Samuel Lichtig, the Zionist Maurycy Taubler, Symon Nowimiast, the engineer Akiba Bucher, Izak Teichtal, and Dr. Schlachet.75 The discrepancy between lists of Jewish Council members might reflect different time periods in its existence, as numerous members of the early Jewish Council were arrested, imprisoned, deported, or killed by the Germans beginning even before the ghetto period.

A few days after the Judenrat was constituted, it was visited by Oberscharfuhrer Siebert and his entourage. The visit was announced ahead of time to the appointed Jewish communal leadership, who waited for the Germans at the offices at 41 Krakówska Street. According to one survivor, “Three limousines arrived and three Gestapo officers with several armed soldiers got out of the cars.”76 The story of what happened next was reported by several survivors. Siebert set out to impress on the new Jewish leadership their exact place under German occupation. He slapped the face of the vice president of the Judenrat, Dr. Goldblatt, because no one had been waiting outside to greet the arriving Germans.77 Siebert then informed the assembled men that the Judenrat was the only body that could represent the Jews, that “Jews are not allowed to communicate with any kind of government apart from the Gestapo [located at] Pomorska Street 2,” that the Judenrat leadership was personally responsible for the activities of the Jews of Kraków, and that “the community has to organize the welfare service to help poor Jews and refugees. In order to do this, they may impose taxes on Jews.” During the brief meeting, the Oberscharfuhrer also repeatedly informed them of the superiority of the Germans and the Gestapo.78

This would not be the only time that German authorities would personally target the Judenrat leaders for abuse. During Passover of 1940, as the non-Jewish Pole Jan Najder described:

an elderly Jew was celebrating the Passover…. It was about 11 p.m. Siebert came and ordered all the Judenrat members to be summoned. My wife, my brother-in-law and I had to wake them up. It was about 3 a.m. when everyone had finally gathered in front of the house of the community. While the people were gathering, Siebert turned them, one by one, so that they faced the wall of the building, their hands above their heads. Nobody knew what would happen, but after standing two hours Siebert let them go. Nobody was killed.79

Salpeter describes the same incident. He does not mention the religious person celebrating Passover but instead notes, “About 10 p.m. of the first night of Passover Seder, the Gestapo gathered all the members of the Judenrat in the community’s meeting room. They gave a lecture on physical exercises; after that, Brandt, the chief of the Gestapo, made all the members go out onto the street, where everyone had to do exercise. They finished in the morning.”80

The Jewish leadership of occupied Kraków did not survive intact to the period of ghettoization. The Germans instituted a mass deportation of Jews out of Kraków during the summer of 1940. Many people, including future Judenrat leaders, were included among those who were forced to leave the city. In an effort to avoid these mass deportations, a number of the Jewish Council members tried to bribe Eugen Reichert, the Stadthauptmann’s (mayor’s) representative in the deportation commission. Reichert was an ethnic German who agreed to accept a set amount of money to reduce the number of Jews to be deported. He, Marek Bieberstein, and four other Jews were arrested in September 1940 for this corruption.81 Bieberstein was sentenced to eighteen months in prison and was eventually released back to the Kraków ghetto.82 After Bieberstein was arrested, the Jewish community was directed by Schenker, who served as interim leader until late November 1940. He was a Kraków native who had owned a wholesale hardware business before the war.83 His role as head of the Jewish Council did not become permanent. Dr. Aron Rosenzweig, a Kraków-born lawyer, became the new Judenrat leader in late November 1940, and remained through the creation of the Kraków ghetto.84 He was eventually arrested during the June 1942 deportations and replaced with David Gutter (b. 1905 in Munich), who was the last of the Kraków ghetto Judenrat heads. He was supported by a council of seven.85

On March 3, 1941, the governor of the Kraków district, Dr. Otto Wächter, announced the establishment of a Jewish residential district (Jüdischer Wohnbezirk) in the Kraków suburb of Podgórze, which lay on the left bank of the Vistula River.86 Jews were required to have residence permits for Kraków to be allowed to move into the ghetto. Although some Jews lived in the area of Podgórze, there was also a large Polish population that had to be moved out of the designated area. Some enterprising Jews were able to organize a swap of their prewar residence with a non-Jew who was forced out of their home, while others were able to move in with friends or family who lived in the area designated for the ghetto. Most Jews incarcerated there, however, were assigned their housing within the restricted area by the Jewish communal housing office.

In the weeks following the decree establishing the ghetto, thousands of Jews fled Kraków to avoid enclosure in the ghetto. The ghetto closed on March 21, 1941. On May 1 of that year, there were 10,873 Jews in the Kraków ghetto.87 The population breakdown was 5,034 men and 5,839 women, with 1,782 of them being children under the age of twelve.88 The 1931 demographics for Kraków had an age distribution of 23.4 percent being children up to the age of fourteen, 68.8 percent being adults between fifteen and sixty years old, and 7.8 percent being adults over the age of sixty. A few weeks later, at the closing of the ghetto, 13.7 percent of the population was over sixty, while children had dropped to 18.4 percent.89 This might be because, as some survivors recalled, elderly Jews who were sick did not have to leave the city, or it might be that a large number of people over sixty were business owners and still needed to guide Germans who had taken over their businesses.90 Another roughly 2,500 Jews were permitted to live outside the ghetto walls in the city of Kraków. This policy was short-lived, however, and in October 1941, all Jews in the city of Kraków and its vicinity were forced to move into the ghetto. As a result, by the end of October 1941, at the height of the ghetto’s population, there were approximately 19,000 Jews.91

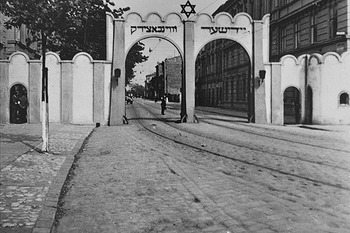

Figure 2.1 Entrance to the Kraków ghetto.

The ghetto area was approximately twenty hectares, including fifteen streets. As one survivor described it, “It was a small ghetto. From north to south, it contained about seven streets; from east to west there were about four or five.”92 The ghetto contained 320 buildings with 2,436 apartments. Approximately 75 percent of the apartments were old, and some were wet and moldy.93 The vast majority (76.7 percent) of the apartments were either studio units (837) or one-room apartments with kitchen (1,027). There were 440 apartments with two rooms and a kitchen, and 108 with three rooms and a kitchen. Only twenty-one apartments in the Kraków ghetto had four rooms and a kitchen, and only three apartments had five rooms and a kitchen.94 In total, there were 3,167 rooms in the ghetto. The population density of the Kraków ghetto was 157 persons per hectare, which was three times the density of the city of Kraków. There were approximately four people per room in the Kraków ghetto.95 This meant that a one-room apartment typically had four to five people in it, a two-room apartment had seven to eight, a three-room apartment had ten to thirteen, a four-room apartment had fifteen to eighteen, and a five-room apartment had twenty to twenty-three people living in it. Some buildings did not have toilets but rather had an outhouse that was shared by the residents.96

A wooden fence – and later a wall evoking the look of Jewish grave markers – was erected around the ghetto. Doors and windows facing the Aryan side of the ghetto were ordered to be bricked closed. This project was not completed, as is evidenced by the fact that members of the Jewish underground were able to sneak in and out of the ghetto through a window facing the Aryan side. In addition to these illegal points of entry and exit to the ghetto, there were four official, guarded entrances to the ghetto: two entrances on Limanowski Street, the main entrance at Podgorski Rynek, and one entrance that was reserved for army vehicles. Additionally, there was an entrance at Lwowska Street as well as one at Plac Zgody. A trolley, Streetcar 3, ran through the ghetto but was forbidden to stop inside the ghetto.97

The German administration over the ghetto included both the civil administration in the form of the Stadthauptmann and the police in the form of the Gestapo’s Department of Jewish Affairs. For most matters, the Jewish Affairs Department of the German security police had sole control. This was an unusual state of affairs for ghettos. Eventually, on June 3, 1942, Hans Frank would abdicate any civilian control over the Jews in the General Government.98 The internal Jewish administration of the ghetto was a continuation of the pre-ghetto administration, which included a twenty-four person Jewish Council. Each member of the council had an administrative oversight function, with more functions added after the closing of the ghetto. The second chairman of the Kraków Jewish Council, Dr. Aron Rosenzweig, was the leader of the ghetto during its creation and sealing.

Jewish Leadership inside the Ghetto

After the creation of all three ghettos, the tasks for each Judenrat expanded greatly. The ghettos became enclosed cities that needed to be administered, fed, policed, provided with health services, and subjected to public health measures. They needed to finance themselves and care for those who could not support themselves. The Jewish ghetto administrations ballooned in size, structure, and responsibilities after the closing establishment of the ghettos. Many would struggle and adapt to find the best ways to provide services. The leaders of the ghettos were human beings, and behaviors ranged from corruption to self-sacrifice.

The closure of these three ghettos created a situation in which the German authorities were able to exert tremendous control over what legally entered the ghettos, particularly in terms of food. In Łódź, Rumkowski quickly discovered that receiving food from the German administration was a difficult business. From the moment the ghetto was sealed, the Provisions Department for the ghetto was made economically independent of the city, so it instituted a tax system of almost 20 percent to pay its expenses, resulting in considerably higher food prices inside the ghetto than outside it.99 Despite this tax, the German ghetto administration rarely allocated the resources to meet even the minimum needs of its inhabitants. The Jewish ghetto administration was often refused adequate food deliveries, such as a request to buy fish for the ghetto or requests for more flour.100 Additionally, the German ghetto administration prohibited ghetto inmates from receiving additional resources from outside the ghetto, strictly enforced antismuggling laws, and confiscated parcels sent to the ghetto.101 The amount of food received by the ghetto was often less than the amount ordered. For example, on July 29, 1941, Rumkowski complained that ninety kilograms of rye flour was missing from a flour shipment.102 The response given by the German ghetto administration on August 4, 1941, was that a 3–4 percent loss was the “normal custom,” and thus ninety kilograms was nothing that could be protested. Often, the money for a food shipment was embezzled, or the food ordered was simply not delivered.103 There were also frequent delays in food delivery. Typical of fluctuations in the food supply is the situation with milk in January 1941. On January 19 of that year, the Łódź ghetto Chronicle was able to report that “the supply of milk fluctuates around 1,000 liters a day, which makes it possible to dispense portions of 200 grams to children up to the age of three and to the sick who have certificates from a physician.”104 Only a week later, the milk supply had dwindled significantly, and there were two days on which no milk was available. Very often there were flour shortages. As the Chronicle recorded, “an event characteristic of the food supply situation last week was the resumption, after a long interruption, of flour delivery to the ghetto.”105 This interruption was particularly devastating as the majority of calories for those in the ghetto were derived from bread.

The Jewish leadership cajoled, bribed, begged, and negotiated with the Nazis to get more resources, time, or reprieves for the populations they oversaw. Sometimes they were successful, but Jewish leaders in all three ghettos were subjected to extremely poor treatment at the hands of the Germans they dealt with on a regular basis. They were sometimes punished for their requests, including being imprisoned and beaten. In the case of Rumkowski and Czerniaków, they were men in their sixties. The deputy director of the Kraków Judenrat, Dr. Goldblatt, also a man in his sixties, was hit by a Nazi overseer. Various other leaders of the Kraków Judenrat and many members of the Warsaw Judenrat were subjected to physical abuse.

The leadership of all three ghettos was profoundly affected by deportations. Bieberstein was arrested for resisting deportations out of Kraków and replaced as Judenrat leader before the ghetto was created. His successor, Rosensweig, lost his life and that of his family for resisting deportations to the death camp Belzec in June 1942.106 Rumkowski suffered a mental breakdown in the ghetto as a result of mass deportations that left him leader of the ghetto effectively in name only. None of the three men survived the war. Czerniaków ended his own life in protest of deportations during the ghetto period. Bieberstein was killed at Płaszów concentration camp before the end of the war. Rumkowski was put on a deportation train, along with his family, to Auschwitz, where he perished.

Conclusion

The Jewish leadership of the three ghettos reflected the prewar attributes and political compositions of their cities. Each leader also had to contend with unique attributes connected to the ways in which their ghetto was administered by the Germans. Ultimately these attributes affected the Jewish leadership’s coping methods for dealing with the food supply and internal food distribution. Various factors, including the different time periods and rates at which ghettos became more closed, created divergent paths for the ghettos and their inhabitants’ experiences including their individually available coping mechanisms. Preferred language, German language ability, and social networks of Jewish communal leadership, which varied between cities, also affected the ghettos’ hierarchies and the ability of different groups of Jews to obtain positions in the Jewish administrations.107

In all three cities, Warsaw, Łódź, and Kraków, Jewish leadership inside the ghettos initially comprised the remaining prewar prominent community members. Many of these leaders remained in their home cities and took on the position due to a sense of duty to their communities. They all suffered abuse and violence from German authorities while simultaneously seeing their own power erode. All the Judenrat leaders contended with shadow leadership run by competing German administrative agencies and had to negotiate between German factions that shaped Jewish ghetto life. The Jewish leaders were often held responsible for the poor ghetto conditions by their contemporaries, who criticized their governance, lack of experience, and personalities. Ultimately all of the leaders lost power over the fate of the ghetto inhabitants and the internal life of the ghettos.