Introduction

The Early Career Archaeologists (ECA hereafter) community is a grassroots initiative of the European Association of Archaeologists (EAA), designed to hear, share, communicate, and act as advocates for issues that affect early career archaeologists. In 2021, the ECA community launched an international online survey aimed at identifying issues faced by early career researchers (ECRs hereafter) in academia. While the ECA community acts to represent the interests of all early career archaeologists, this survey was limited to those wishing to pursue an academic career in research to keep it to a manageable size, and to specifically investigate issues faced within academia. A separate survey of ECAs pursuing a career in commercial archaeology is in preparation (see Siegmund & Scherzler, Reference Siegmund and Scherzler2019 for a recent survey of commercial archaeologists in Germany).

The impetus for the formation of the ECA community and the attendant survey was the large numbers of EAA members (especially ECRs) expressing concerns about the profession and their own uncertain place and future within it. Much research has been devoted in recent years to the problems faced by ECRs in broader academia, such as recent surveys worldwide (Woolston, Reference Woolston2017, Reference Woolston2019) and in Europe (Swider-Cios et al., Reference Swider-Cios, Solymosi and Srinivas2021), or among UK researchers (Wellcome, 2020), German scientists (Abbott, Reference Abbott2019), North American field researchers (Clancy et al., Reference Clancy, Nelson, Rutherford and Hinde2014), and Australian scientists (Christian et al., Reference Christian, Johnstone, Larkins, Wright and Doran2021). Surveys of archaeology and related disciplines and studies of workplace statistics have also addressed the plight of ECRs among North American archaeologists (Altschul & Patterson, Reference Altschul, Patterson, Ashmore, Lippert and Mills2010; Hoggarth et al., Reference Hoggarth, Batty, Bondura, Creamer, Ebert and Green-Mink2021), Australian archaeologists (Mate & Ulm, Reference Mate and Ulm2021), European anthropologists (Fotta et al., Reference Fotta, Ivancheva and Pernes2020), and UK historians (McDonald, Reference McDonald2017; Atkinson et al., Reference Atkinson, Bardgett, Budd, Finn, Kissane and Qureshi2018). These surveys and employment statistics are often not specific to archaeology or are gathered for individual countries; the latter obscure broader patterns and do not reflect the transnational character of many academic careers in archaeology.

Challenges faced by ECRs, not only in Europe but across the globe, should be seen within the context of the wider issues created by changes to the teaching of archaeology in universities. In the UK, for example, several archaeology departments have faced difficulties for years, caused by a drop in student numbers at some institutions, an increase in tuition fees, and the withdrawal of student loans for second degrees (Horton, Reference Horton2012; Shepperson, Reference Shepperson2017). Planned cuts, by as much as fifty per cent to the UK Higher Education Teaching Grant to archaeology were only saved at the last minute when the Education Secretary intervened (Shaw, Reference Shaw2021). In this context, the announcement of the forthcoming closure of the internationally respected archaeology department at the University of Sheffield (Newton, Reference Newton2022), as well as similar developments at the University of Worcester (Rehman, Reference Rehman2021), have caused wide concern.

The EAA and the ECA wanted to hear from a wide range of international early career research archaeologists, as they represent the future of the discipline. The goal of this pilot survey was to raise awareness of the issues that ECRs face and to provide quantifiable statistical evidence of concerns voiced widely, albeit anecdotally, within the community. Furthermore, the survey will help the EAA formulate best practice guidelines, and it is our hope that, by raising awareness, further support will be made available for ECRs and opportunities for reflection and change created.

Methodology

The survey was created using Google Forms and consisted of thirty-seven questions (see Supplementary Material, Table S1). These questions examined: the nature of the ECRs’ employment; their feelings about their past employment; future opportunities; financial situation; support systems; and other aspects of their working life. Questions included a mixture of multiple-choice questions, ratings on a 5-point scale, and open-ended questions that allowed participants to elaborate and clarify their answers.

This survey was conducted on behalf of the EAA with prior approval from the EAA Executive Board. In adherence with ethics guidelines established by The European Commission (2013, 2021), participation in the survey was voluntary and consent could be withdrawn at any time. Following these guidelines, as well as those regarding data management from the European Association of Social Anthropologists (2018), no personal or sensitive information was gathered or stored, including names and email/IP addresses. Any potentially identifying information (age, background, location, etc.) was stored securely and apart from the remainder of the survey responses. In the interests of anonymity, published here are the collated and analysed results of the survey, not individual responses to any questions. Where relevant, small snippets from individual responses are quoted, but in a decontextualized form that avoids any potentially identifying details. Most questions gave an option of ‘I would prefer not to say’ so that participants could only respond to questions they felt comfortable with.

Participants could also include information they felt was important but had not been covered in the survey. To ensure anonymity, no names, email addresses, or other identifying information were collected. The survey was launched on 26 January 2021 and ran until 1 October 2021. It was promoted mainly through social media including the ECA Twitter (@ECArchaeologist) and Facebook accounts, the ECA website (https://ecarchaeologists.com/) and that of the EAA (https://www.e-a-a.org/). The target group was ECRs pursuing a career in academia (i.e. postgraduates and post-docs), although the survey was open to all career stages. We generally defined early career archaeologists as ‘professionals who have not yet held a position of responsibility or authority within their institution, often marked by tenure’, but we accepted self-identification, i.e. if you feel like an ECA, then you are one.

Not all issues potentially affecting ECRs were covered within this first survey, as we wished to keep it relatively short to maximize the completion rate, and to avoid personal questions that might identify respondents, as required by the strict European data privacy laws. We gave prominence to questions relating to job and financial stability, in addition to the ECRs’ experience of their treatment. The primary limitation of this pilot survey is that many ECRs face discrimination for reasons not adequately covered by our questions (e.g. colour, nationality, ethnic origin, religion or belief, age, sex, sexual orientation, ableism, and transphobia), and we regret that we were unable to cover the impact of these factors in detail. Recent work is illuminating the way intersectional (see Crenshaw, Reference Crenshaw1991) systems of discrimination and oppression affect archaeologists in academia (Sterling, Reference Sterling2015; Rutecki & Blackmore, Reference Rutecki and Blackmore2016; Heath-Stout, Reference Heath-Stout2020a, Reference Heath-Stout2022). A more in-depth survey planned by the ECA will include questions aimed at gauging how intersecting identities shape the experiences of ECRs differently. In the meantime, we attempted to include these issues by asking open-ended questions where ECRs could share their experiences. We decided against reproducing any of the long answers here, even in redacted format, to avoid causing more stress to respondents and any legal concerns.

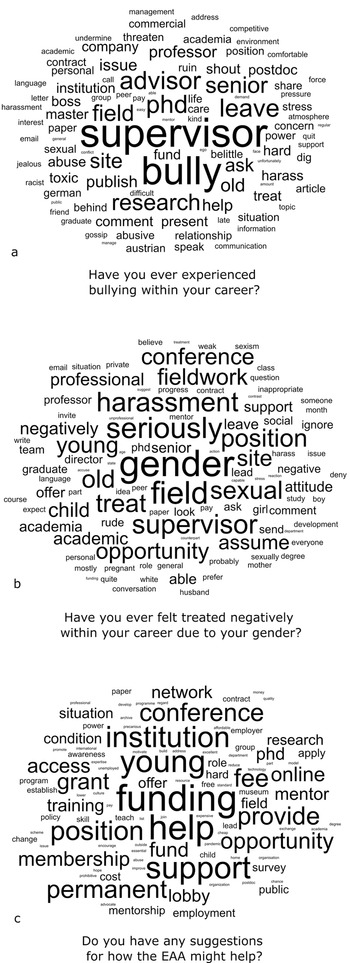

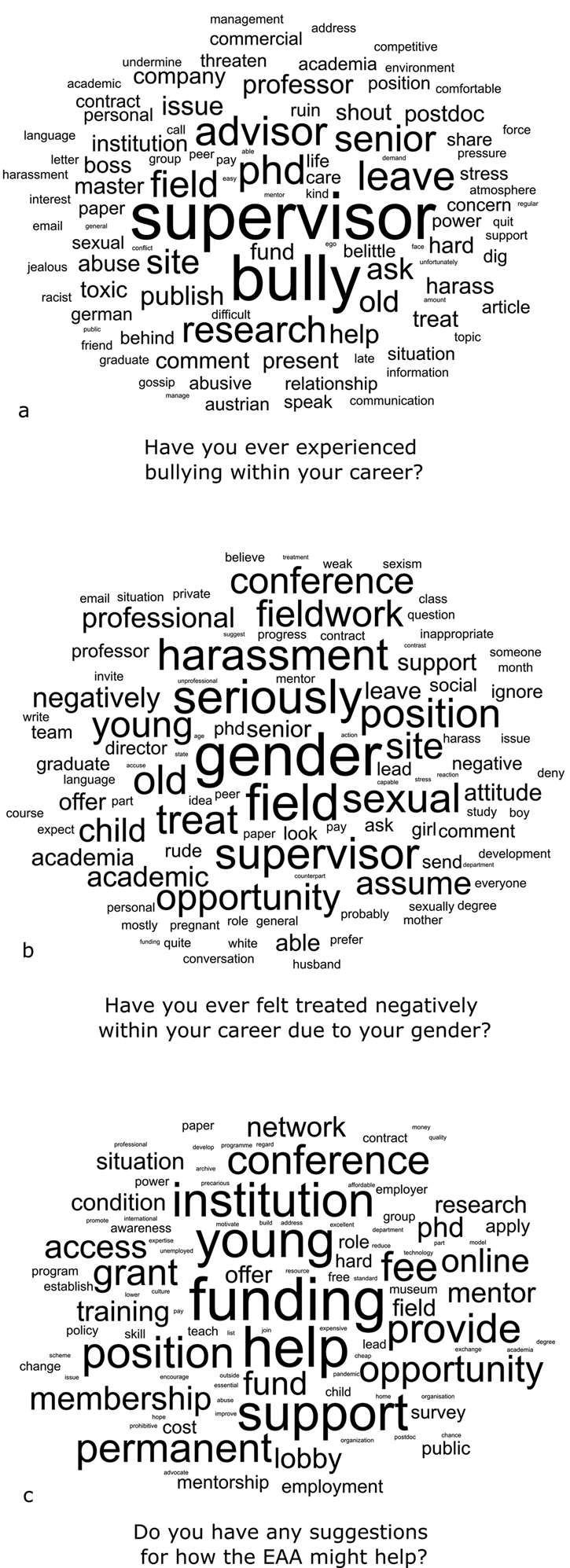

Open-ended questions were analysed using word clouds generated from the responses regarding bullying, gender discrimination, and suggestions for the EAA. These word clouds were generated in Matlab using the Text Analytics Toolbox. Parts of speech were analysed, with prepositions, pronouns, interjections, and punctuation excluded, as were words shorter than two letters and longer than fifteen. Manual exclusions were also made to remove common but neutral words like ‘archaeologist’, ‘person’, and ‘place’. The words in the word clouds were scaled by frequency of occurrence, but not context or sentiment. As many words can be used positively or negatively, the word clouds should only be used to gauge the topics most frequently raised by ECRs in the long-form responses.

Results

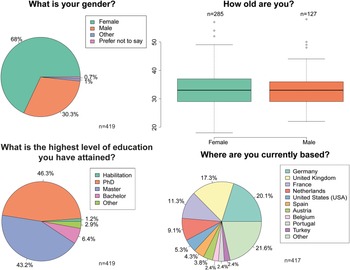

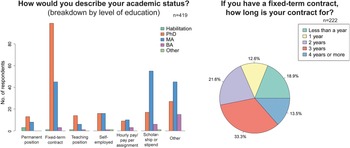

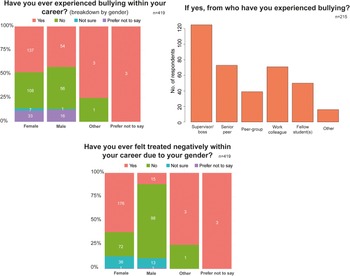

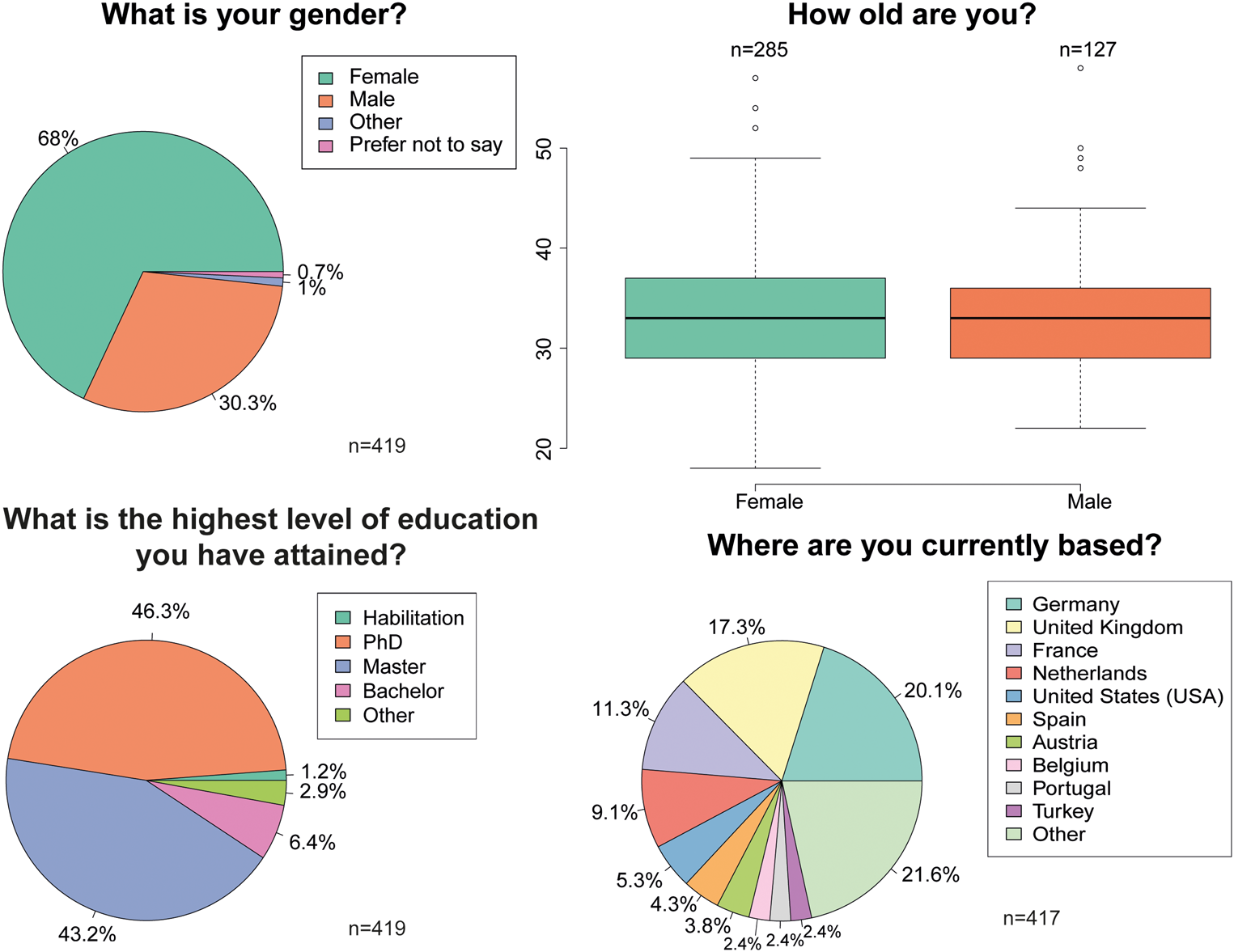

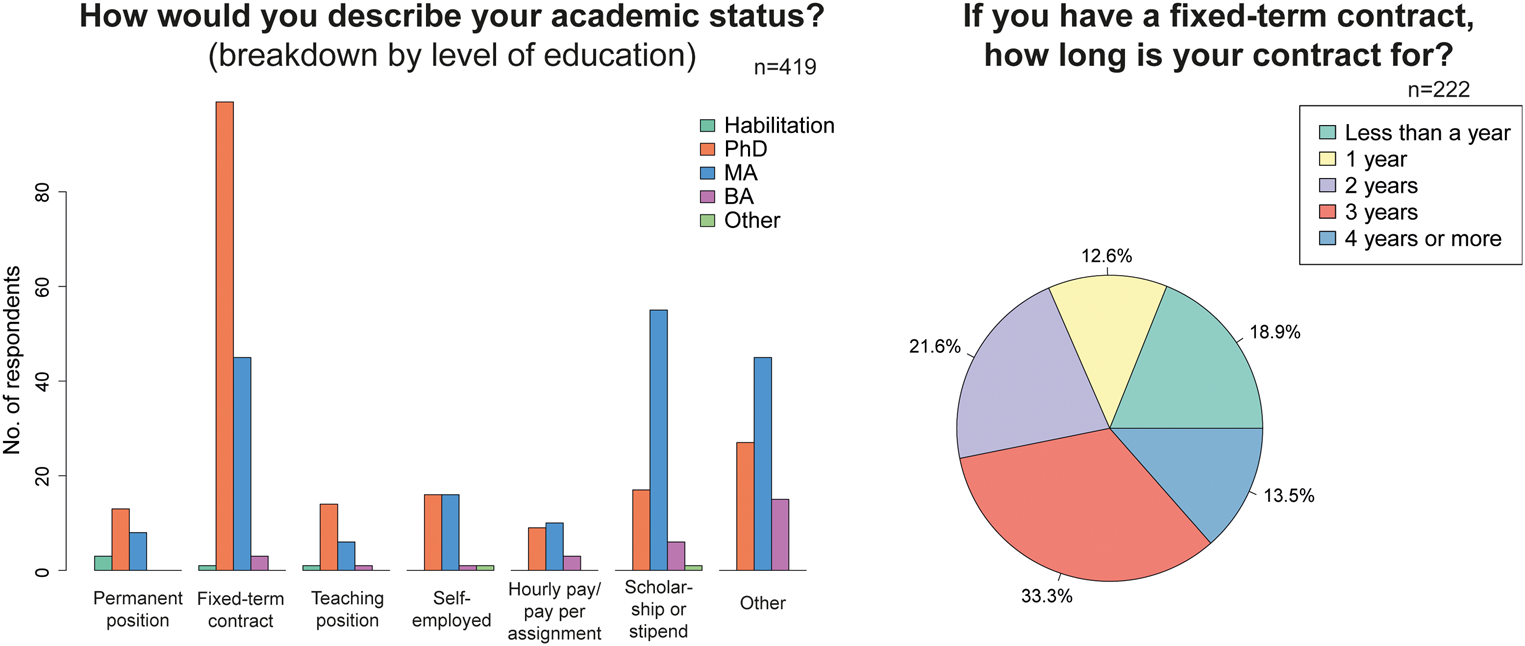

The figures below are also available in the Supplementary Material as greyscale images for colourblind readers (Figures S1-S10). The survey had 419 respondents from forty countries worldwide (Figure 1), with 86.3 per cent based in Europe (including 84 respondents in Germany, 72 in the UK, 47 in France), 6.0 per cent in the US and Canada, 4.1 per cent in Western Asia (primarily Türkiye and Israel), and a few respondents in South and Southeast Asia, Oceania, Latin America, the Caribbean, and North Africa. Two-thirds of participants identified themselves as female (68.0 per cent), 30.3 per cent as male, 1.0 per cent as other, and 0.7 per cent preferred not to say. The average age of the respondents was the same for males and females (33 years old). At the time of the survey, the highest qualification of 46.3 per cent of respondents was a PhD, while for 43.2 per cent it was an MA or equivalent academic qualification. The majority of respondents (61.1 per cent) described their position as research, sometimes combined with teaching and/or administration; 5.5 per cent were mainly teaching, 2.6 per cent were engaged in administration, 2.6 per cent were support staff, others preferred not to say or listed different activities, such as consulting, fieldwork, and editorial management. A breakdown of academic/professional status by level of education is given in Figure 2.

Figure 1. Profile of the respondents.

Figure 2. Academic and professional status.

Long-term precarious employment and its personal toll

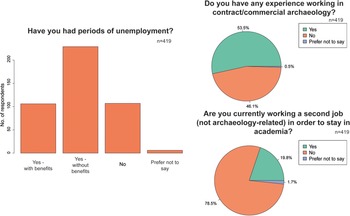

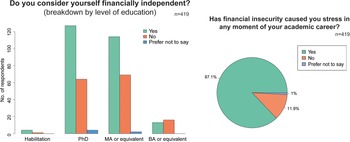

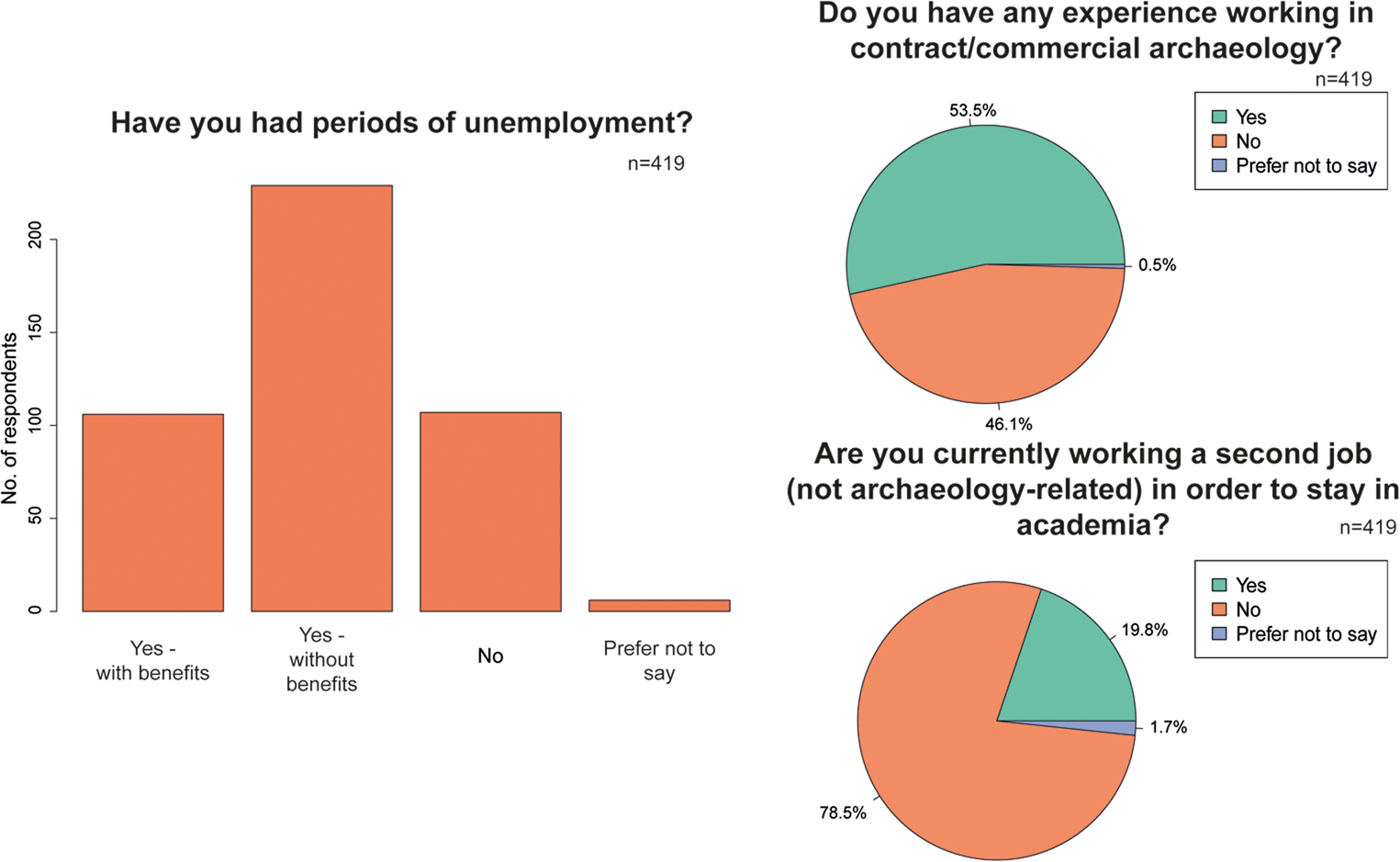

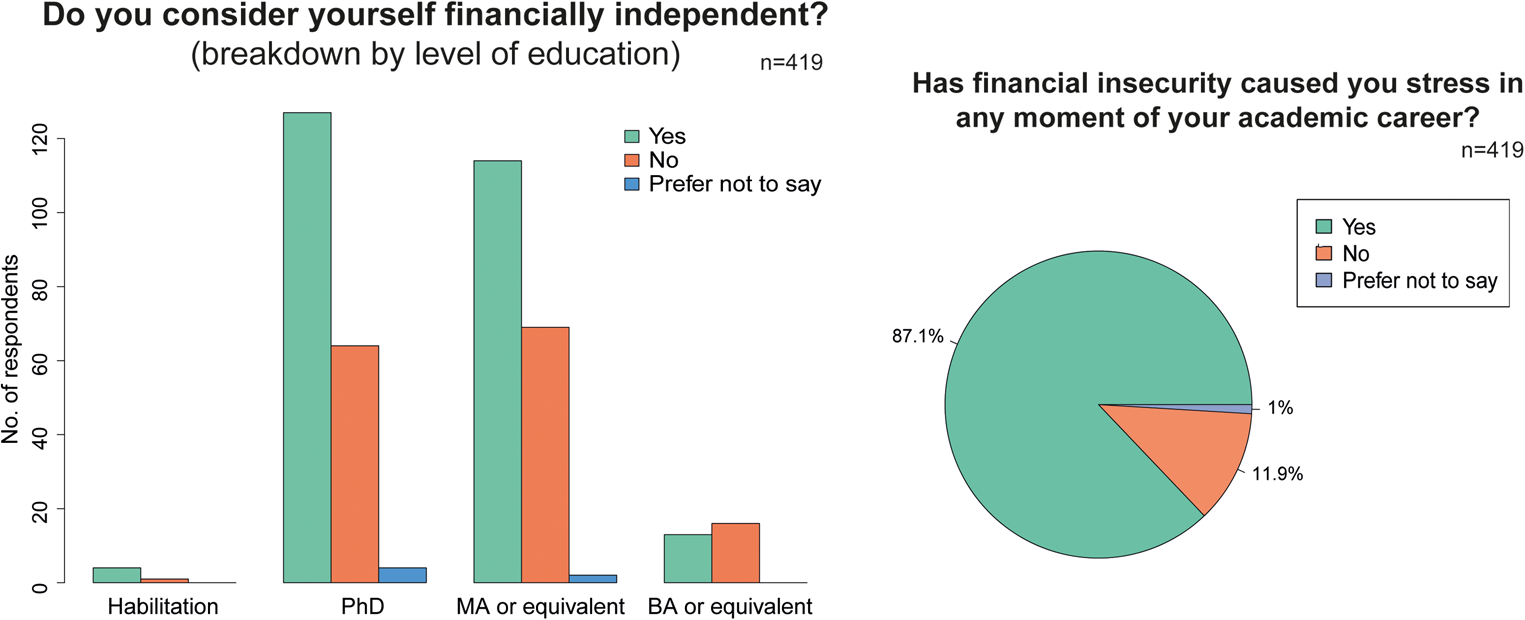

More than 71 per cent of ECRs who took the survey wanted to stay in academia. To support themselves, 19.8 per cent of respondents worked in non-archaeological second jobs; 53.5 per cent spent time in contract/commercial archaeology (Figure 3). Most respondents had experienced at least one period of unemployment, 54.7 per cent taking no unemployment benefits, suggesting that personal finances were being impacted; 31.5 per cent of respondents considered their earnings in academia as insufficient for basic necessities, with a further 21.2 per cent not earning any salary. Financial problems appeared to continue during the protracted post-doctoral phase, with many ECRs stating that they are not financially independent, including 32.8 per cent of PhD holders (Figure 4).

Figure 3. Unemployment and second jobs.

Figure 4. Financial issues.

While female and male respondents were equally likely to have encountered periods of unemployment (73.7 vs 73.2 per cent respectively), more women reported earning no salary (23.5 vs 15.7 per cent) and periods of under-employment, i.e. working for fewer hours than desirable or financially sustainable (68.4 vs 56.7 per cent). Our survey thus suggests that women are being disproportionately affected by employment instability and are more likely to accept flexible working conditions and unpaid traineeships.

Respondents were very pessimistic about their chances of moving to secure employment, with many reporting a fear of failure and pressure to deliver. Only 20.7 per cent described the prospect of a permanent job in archaeology as ‘likely’ or ‘highly likely’. Even fewer (7.2 per cent) were convinced by their own institution's ability to create a permanent position for them in future. When asked why their institution was unlikely to do so, many described permanent positions as being extremely rare (45.0 per cent) and institutions not recruiting internally (4.5 per cent). Lack of funding was mentioned by 22.9 per cent of participants; COVID-19 related cuts may have exacerbated this situation. Several respondents mentioned not fitting into the framework of their institution or absence of opportunities in their chosen field of specialization (6.14 per cent). A lack of future career development options was identified as a source of stress by 84.2 per cent of respondents, suggesting that higher education institutions are failing to provide career options or ensure that ECRs participate in continuing professional development.

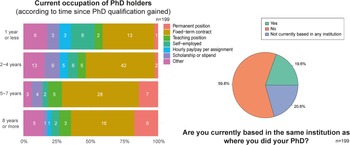

Judging by our respondents’ experiences, it is by no means guaranteed that post-doctoral fellowships will lead to an academic appointment, although extended access to fellowships does increase the chance of gaining a tenure-track position (Figure 5). Those advanced ECRs typically spent eight or more years after obtaining their doctorates in temporary positions, including post-doctoral fellowships usually lasting between one and three years without possibility of extension. Scholarships or stipends are even more precarious than fixed-term research and/or teaching positions, with holders frequently not regarded as regular employees; they thus miss out on social security benefits, pensions, and professional advantages. Scholarships and stipends are, for instance, excluded from calculations of work experience in most German academic institutions, leading to lower long-term salary expectations for beneficiaries.

Figure 5. Occupation of PhD holders.

To stay competitive, ECRs with post-doctoral positions (e.g. Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions) are expected to be highly mobile, and on average will change institutions every two or three years. Mobility between countries and institutions can be enriching and has long been a feature of the academic career paths, but it often comes at a significant personal cost. Among respondents, 118 had obtained their most recent degree from a different country than their country of birth, with forty-nine either returning to their country of origin or going to a third country after PhD graduation. As many post-doctoral opportunities are limited to within three to eight years of completing a PhD, some ECRs find themselves automatically ejected from the academic ladder. Others end up competing with established candidates for European Research Council (ERC) grants. Common comments included: ‘The lack of financial support for researchers without [a] position is a real issue…’ and ‘I am now considered […] too old for many funding programmes’. In Germany, for example, there are restrictions on how many years one can work for academic institutions without a permanent contract (Wissenschaftszeitvertragsgesetz, 2007). Among respondents, 61.3 per cent described employment competition as a cause of stress in their career.

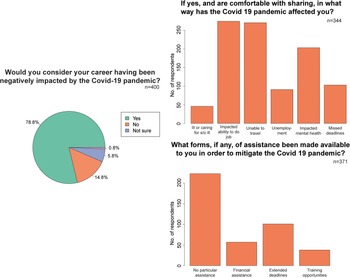

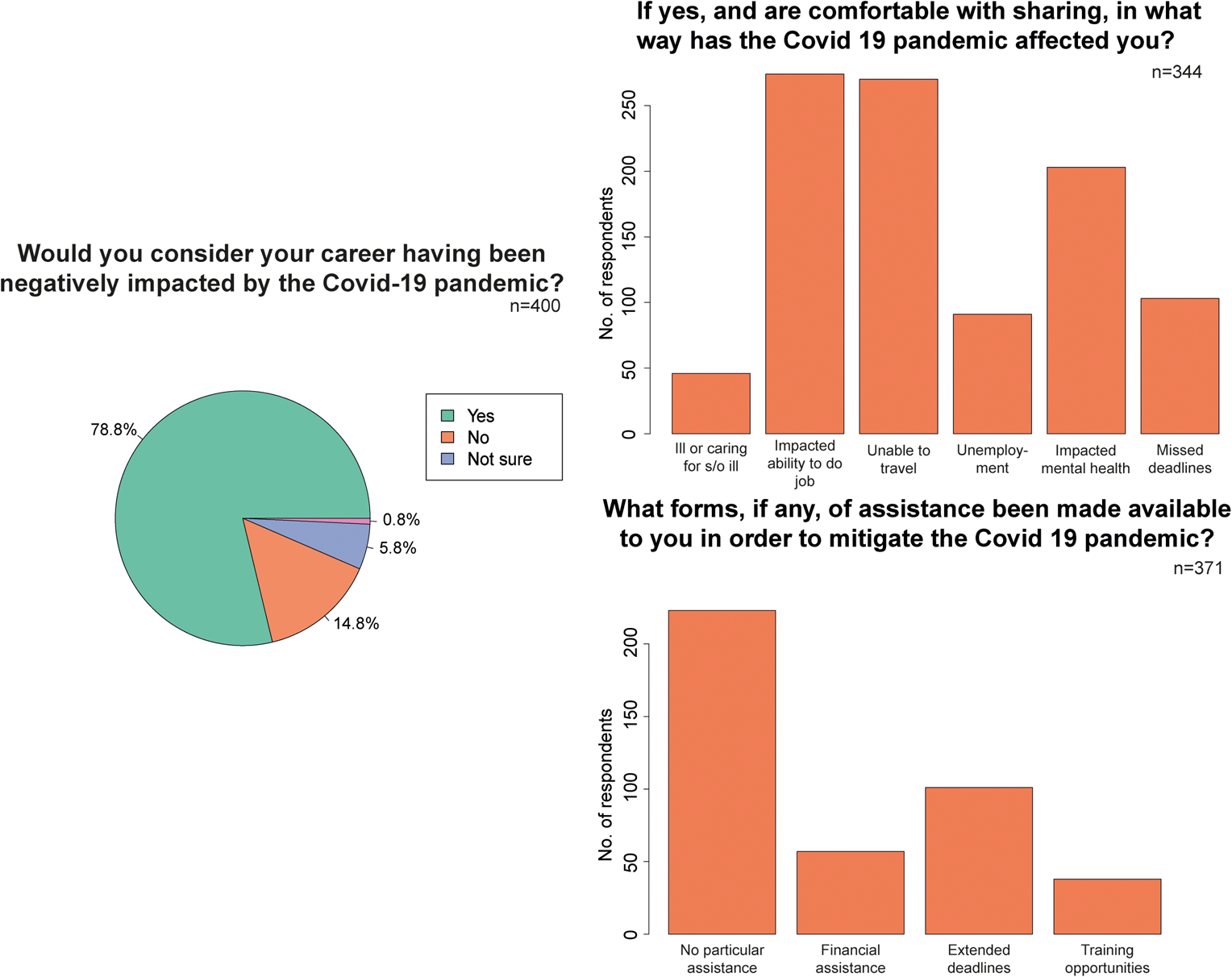

Our survey also confirms that, although the long-term effects of the COVID-19 pandemic are still unknown, it has had a significant impact on ECRs, who have had to deal with reduced funding opportunities and delayed job openings: 75.2 per cent of respondents consider their career to have been negatively affected by the pandemic, whether through lost opportunities, illness, unemployment, or negative impact on mental health (Figure 6). For 53.2 per cent of respondents, no particular special assistance was offered by their institution. Some, however, received assistance, with 13.6 per cent reporting financial assistance, 24.1 per cent having deadlines extended, and 9.1 per cent receiving training (e.g. for online teaching).

Figure 6. Covid-19 Pandemic.

Inequitable practices, lost opportunities, and dismissed concerns

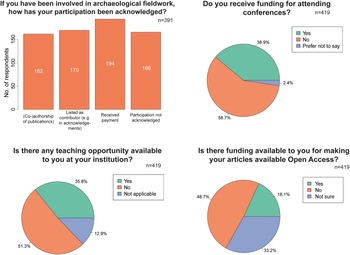

The survey's questions relating to the opportunities available to ECRs (Figure 7) revealed that only 38.9 per cent of respondents received funding for attending conferences, while teaching opportunities were available to only 35.8 per cent. For unemployed ECRs, the open-ended comments made clear that losing their academic affiliation was a major concern. Multiple respondents reported losing access to library resources and IT facilities. Several ECRs reported not being able to afford the fees to join professional organizations such as the EAA. It is regrettable that those who most need to be members and attend conferences are often the least able to do so.

Figure 7. Recognition and opportunities.

When asked if they had experienced difficulties publishing in peer-reviewed journals, 34.8 per cent responded ‘yes’, and a further 30.8 per cent responded ‘N/A’, suggesting either no prior experience or no expectations to publish. The difficulties mentioned ranged from not knowing how to write an academic paper to having no funding for language correction, bad experiences with reviewers, and long turnaround times from journals. Several respondents reported being treated unfairly during the peer-review process due to their status as inexperienced academics. Such a perception is difficult to gauge for accuracy given the common practice of blind reviews, but it highlights distrust of the process and indicates an area of concern, as publication plays a key role in career progression. Only 18.1 per cent of respondents had access to Open Access funding for publications.

Acknowledgement and/or inclusion in publications of involvement in excavations, surveys, and laboratory work tended to be an area of concern. In reply to the question, ‘if you have been involved in archaeological fieldwork (survey, excavation), how has your participation been acknowledged?’, 42.5 per cent answered ‘participation not acknowledged’, meaning that their name did not appear in any record, including even the acknowledgement sections at the end of articles (Figure 7). It is worth noting that, as part of its ‘multivocality agenda’, the Çatalhöyük Research Project in Türkiye, under the directorship of Ian Hodder (1993–2018), started crediting all team members in newsletters and reports, regardless of their responsibility at the site (Çatalhöyük Research Project, 1995–2017).

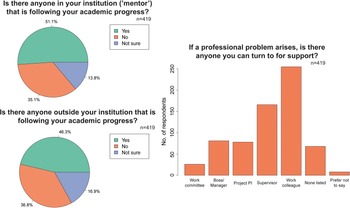

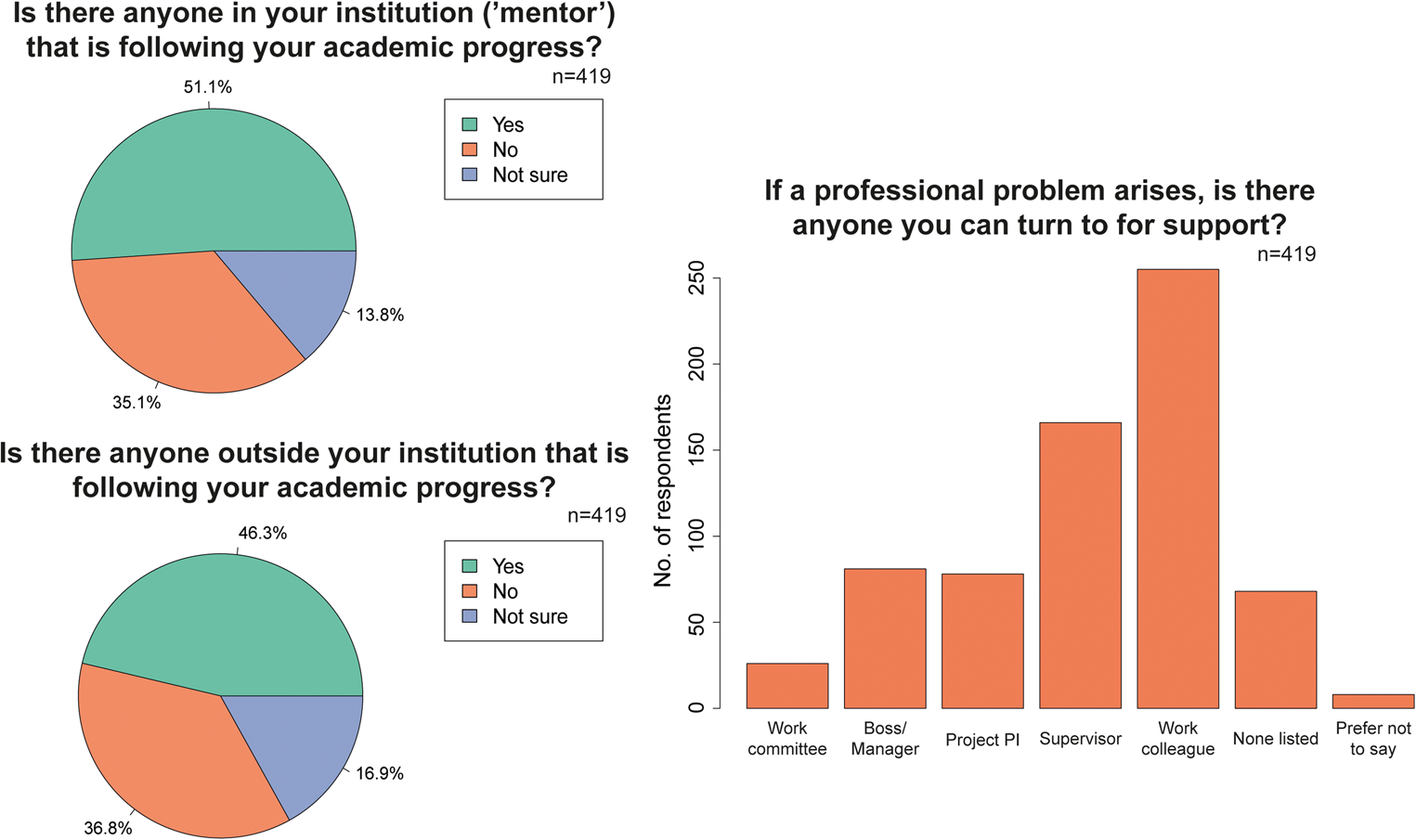

The lack of robust support mechanisms to accommodate the needs of ECRs at many host institutions, e.g. mentors, appointed peer supporters, work committees, ombudspersons, and unions, was also raised. Our survey shows that ECRs are largely unaware of support and protections if they are available, with only 6.2 per cent of respondents turning to work committees when a professional problem arose (Figure 8). ECRs were more likely to consult a work colleague (60.9 per cent), their supervisor (38.4 per cent), or manager (19.3 per cent). Concerningly, 35.1 per cent of respondents reported having no-one at their institution following their academic progress, with a further 13.8 per cent not sure, highlighting the need for better mentoring systems both inside and outside institutions.

Figure 8. Support and representation.

Bullying and discrimination

We also asked participants, if they felt comfortable doing so, to share their experiences of bullying and discrimination in an open answer format (Figure 9a). We received over 180 comments. The Academic Parity Movement, a non-profit organization created to protect human rights in academic institutions, defines bullying by an academic superior as ‘sustained hostile behaviour … including, but not limited to, ridiculing, threatening, blaming, invasion of privacy, [and] put-downs’ (Academic Parity Movement, n.d.).

Figure 9. Word clouds generated from a selection of long-form responses.

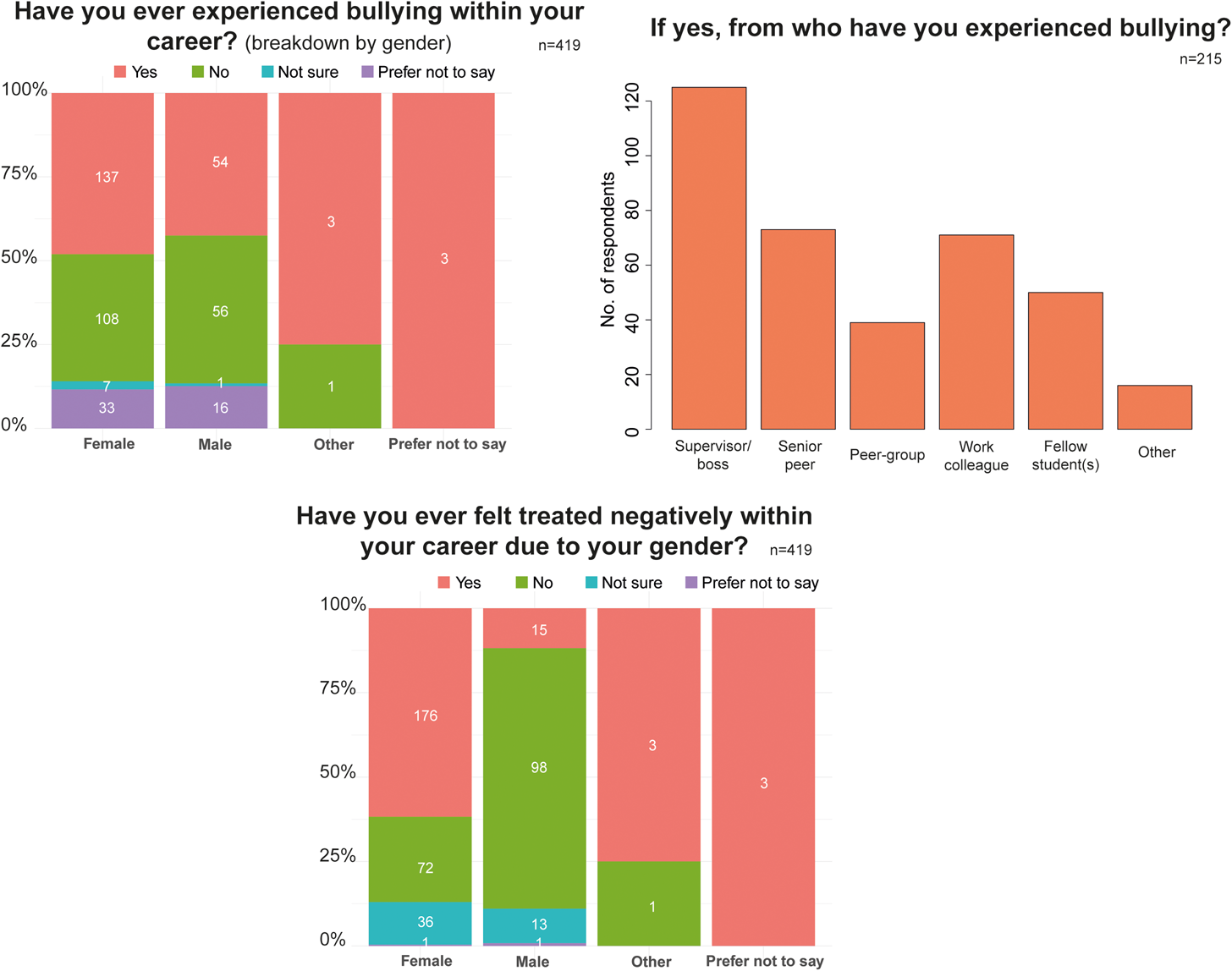

Nearly half (47.0 per cent) of respondents experienced bullying. In most cases, this came from someone in a higher position in the academic hierarchy (Figure 10). The work environment in archaeology (both academic and commercial) was repeatedly described as both ‘toxic’ and ‘very competitive’, with many noting a lack of support from supervisors when they encountered problems. Verbal abuse, especially ‘shouting’ and being ‘talked down to’, or addressed in a demeaning manner, was also repeatedly highlighted. Several ECRs reported having experienced abuses of power (eleven comments), such as not having their work acknowledged, or people in a higher position demanding authorship of publications to which they did not contribute.

Figure 10. Bullying culture in the workplace.

To the question ‘have you ever felt treated negatively within your career due to your gender?’, most affirmative answers came from women (61.8 per cent of female respondents vs 11.8 per cent male) (Figure 10). Furthermore, most of the open answers (Figure 9b) detailing gender discrimination also came from women (99 out of 108 comments). Most often, women stated that they experienced sexist attitudes during fieldwork, being ‘treated as unskilled due to being a woman’, considered ‘too weak for fieldwork’, and sometimes made to do activities considered less physical and more ‘suitable’ such as working in the kitchen, cleaning, laboratory work, sieving, or paperwork. Several women noted that they felt that they were ‘taken less seriously’ than men, ‘ignored’, had comments made about their appearance, or had experienced people assuming they were secretaries or junior to male colleagues because they were women. These comments sadly echo decades of experiences of women archaeologists (Gero, Reference Gero, Gero, Lacy and Blakey1983, Reference Gero1985).

Discrimination before, during, and after pregnancy was mentioned in eleven comments. Some women stated that they were overlooked for available positions or experienced a lack of support from advisors or institutions regarding opportunities to advance their career as they will ‘find a husband’ and/or ‘get pregnant’. While pregnant, some stated they had to deal with ‘huge pressure’, while others had a difficult time taking maternity leave. Once mothers, some women felt discriminated against by being isolated and excluded from fieldwork, projects, positions, or group activities. In addition, some mentioned it was their partners who benefited from support or inclusiveness, the men also having taken parental leave. A small number of men also reported experiencing gender-based discrimination.

Harassment and sexual harassment were reported in fourteen comments from women and one from a man. These serious incidents were exacerbated by many of these respondents not receiving adequate support. Lastly, several respondents disclosed bullying and discrimination related to identity and background, such as racist comments, being belittled for the way they spoke and looked, for being disabled or queer, or for belonging to a certain social class. Future surveys and research will further explore how peoples’ backgrounds and identities exacerbate existing inequities within academia.

Discussion

These troubling results need to be placed within the context of research on the problems faced by ECRs within the wider international higher education sector. Such research confirms this bleak picture. Although the pursuit of an academic career has always been challenging, involving instability, high mobility, isolation, and poor pay and conditions, evidence from such research and the outcome of our survey suggest that ECRs face increased challenges and worsening conditions in the early twenty-first century.

Challenges faced by ECRs within wider contexts

The primary challenge faced by today's ECRs appears to be an increasingly casualized and precarious job market in which a growing number of graduates compete over scarce positions. This instability has led to a raft of negative outcomes, affecting economic stability and wellbeing, both physical and mental. ECRs often report a deteriorating work–life balance (Bozzon et al., Reference Bozzon, Murgia, Poggio and Rapetti2017; Krilić et al., Reference Krilić, Istenič, Hočevar, Murgia and Poggio2018; Fotta et al., Reference Fotta, Ivancheva and Pernes2020); feelings of being overworked and ‘burnout’ (Hartung et al., Reference Hartung, Barnes, Welch, O'Flynn, Uptin and McMahon2017; Chapman et al., Reference Chapman, Bicca-Marques, Calvignac-Spencer, Fan, Fashing and Gogarten2019; Woolston, Reference Woolston2019; Abbott, Reference Abbott2020); imposed mobility (Balaban, Reference Balaban2018; Fotta et al., Reference Fotta, Ivancheva and Pernes2020); mental health concerns (Levecque et al., Reference Levecque, Anseel, De Beuckelaer, Van der Heyden and Gisle2017; Woolston, Reference Woolston2019), and workplace bullying, harassment, and assault (Clancy et al., Reference Clancy, Nelson, Rutherford and Hinde2014; Abbott, Reference Abbott2019, Reference Abbott2020; Voss, Reference Voss2021a, Reference Voss2021b).

Almost all ECRs face poor job security but its severity is often asymmetric, depending on identity and background (Atkinson et al., Reference Atkinson, Bardgett, Budd, Finn, Kissane and Qureshi2018). For instance, mirroring the survey results, research in wider higher education indicates that women encounter unfavourable wage gaps, more inequitable hiring practices, publishing and citation biases, discrimination due to pregnancy and childrearing, and are often constrained by gendered divisions of labour both inside and outside academia, as well as experience higher rates of bullying, harassment, and assault (Bozzon et al., Reference Bozzon, Murgia, Poggio, Murgia and Poggio2018; Herschberg et al., Reference Herschberg, Benschop, van den Brink, Murgia and Poggio2018a; Krilić et al., Reference Krilić, Istenič, Hočevar, Murgia and Poggio2018; Abbott, Reference Abbott2019; Cech & Blair-Loy, Reference Cech and Blair-Loy2019; Woolston, Reference Woolston2019; Fotta et al., Reference Fotta, Ivancheva and Pernes2020; Heath-Stout, Reference Heath-Stout2020a, Reference Heath-Stout2020b; Christian et al., Reference Christian, Johnstone, Larkins, Wright and Doran2021; Maas et al., Reference Maas, Pakeman, Godet, Smith, Devictor and Primack2021; Mate & Ulm, Reference Mate and Ulm2021; Voss, Reference Voss2021a, Reference Voss2021b; Mori, Reference Mori2022). Moreover, the rate of harassment and assault is particularly high within academic disciplines involving fieldwork (Clancy et al., Reference Clancy, Nelson, Rutherford and Hinde2014; Almansa Sánchez & Díaz de Liaño, Reference Almansa Sánchez and Díaz de Liaño2019). The universities’ use of non-disclosure agreements in sexual harassment cases involving staff and students has rightly drawn criticism (Weale & Batty, Reference Weale and Batty2016).

A high rate of mobility among ECRs, often involving studying and working in foreign countries, leaves many feeling isolated and uprooted, as well as affecting the job prospects of those with family and other non-academic commitments (Balaban, Reference Balaban2018). Researchers from the Global South face additional biases regarding publishing, citations, and grants (Brodie et al., Reference Brodie, Frainer, Pennino, Jiang, Kaikkonen and Lopez2021; Maas et al., Reference Maas, Pakeman, Godet, Smith, Devictor and Primack2021; Mori, Reference Mori2022). Language barriers also create inequalities due to the dominance of English in the publishing sphere (Jain et al., Reference Jain, Iyengar and Vaishya2020; Nuñez & Amano, Reference Nuñez and Amano2021; Khelifa et al., Reference Khelifa, Amano and Nuñez2022). A comprehensive report from the UK Royal Historical Society recently found marked inequities in hiring practices, remuneration, instances of stereotyping, harassment, and bullying based on race and ethnicity (Atkinson et al., Reference Atkinson, Bardgett, Budd, Finn, Kissane and Qureshi2018).

Workplace bullying is well documented in all areas of academia, not just archaeology. A recently published article giving advice to victims found that, in any twelve-month period, 25 per cent of faculty members report being bullied, while 40–50 per cent say they have witnessed others being bullied (Gewin, Reference Gewin2021).

Causes of precarity

In academia generally, the last two decades have witnessed a strong growth in the number of doctoral graduates and short-term contracts, while available faculty positions have stagnated (Larson et al., Reference Larson, Ghaffarzadegan and Xue2014; Bradfield, Reference Bradfield2016; Bozzon et al., Reference Bozzon, Murgia, Poggio and Rapetti2017; Levecque et al., Reference Levecque, Anseel, De Beuckelaer, Van der Heyden and Gisle2017; McDonald, Reference McDonald2017; Andalib et al., Reference Andalib, Ghaffarzadegan and Larson2018; Herschberg et al., Reference Herschberg, Benschop and van den Brink2018b; Holzinger et al., Reference Holzinger, Schiffbänker, Reidl, Hafellner, Streicher, Murgia and Poggio2018; Richardson et al., Reference Richardson, Wardale and Lord2019). This has led to an oversaturated academic job market whose members constitute a kind of ‘precariat’, reflecting the precarious nature of their career path and employment prospects. The precariat forms a burgeoning class of workers coerced into flexible and insecure employment (Standing, Reference Standing2011).

The plethora of qualified candidates vying for a shrinking number of positions creates conditions for exploitative contracts and deteriorating working environments (McDonald, Reference McDonald2017; Andalib et al., Reference Andalib, Ghaffarzadegan and Larson2018; Richardson et al., Reference Richardson, Wardale and Lord2019). A saturated job market is a replaceable job market. Those on short-term contracts are discouraged from dissent or complaint by the large numbers of candidates competing for their job (Giroux, Reference Giroux, Denzin and Giardina2014). While the precariat emerged first in other sectors, the increasing casualization of academia has led some to identify the job insecurity of early careers in academia as part of this phenomenon (Ginn, Reference Ginn2014; McDonald, Reference McDonald2017; Bozzon et al., Reference Bozzon, Murgia, Poggio, Murgia and Poggio2018; Herschberg et al., Reference Herschberg, Benschop and van den Brink2018b; Mauri, Reference Mauri, Cannizzo and Osbaldiston2019; Fotta et al., Reference Fotta, Ivancheva and Pernes2020). University employees on short-term contracts usually also miss out on vital opportunities for continuing professional development, progress review, and training.

Andalib et al. (Reference Andalib, Ghaffarzadegan and Larson2018: 675) label this a ‘labour force in waiting’, pointing out that the queue of eager post-docs hoping for a long-term appointment is getting longer, as is the average time spent in the ‘queue’. Moreover, this disposable body of jobseekers introduces class-based inequities in the hiring process, as the likelihood of acquiring a faculty post is beginning to relate more to an ability to remain in the queue, an ability that depends on safety nets, financial security, and high mobility.

This instability promotes unkind working environments. A recent survey of academics’ experience of research culture revealed that 78 per cent of researchers believe high levels of competition are creating toxic working conditions, with many academics voicing concerns about pressures to publish, high levels of stress, and a culture of long working hours (Wellcome, 2020). High rates of stress are common among early (and later) career researchers (Allmer, Reference Allmer2018; Abbott, Reference Abbott2020), with stress given as one of the most common reasons for leaving academia (Aarnikoivu et al., Reference Aarnikoivu, Nokkala, Siekkinen, Kuoppala and Pekkola2019).

Much of this precarity is driven by government policy and is enforced by the contraction of public funding for the university sector (Bozzon et al., Reference Bozzon, Murgia, Poggio and Rapetti2017: 336). The increasing neo-liberalization and marketization of the higher education sector, in Europe and globally, has led to a greater prevalence of short-term decision-making by university managers, who appear to emulate strategies from profit-oriented corporations. As such, universities are increasingly regarded as business-first centres of academic excellence, with learning taking second place. This systemic crisis is also reflected in the development of a burgeoning bureaucratic apparatus created by stagnant faculty staffing (Ginn, Reference Ginn2014; Giroux, Reference Giroux, Denzin and Giardina2014). Moreover, a greater reliance on often inadequate metrics for quantifying the worth of researchers (e.g. impact factors, grant size, teaching evaluations, etc.) perpetuates the myth of meritocracy and overlooks the social value of research (Ginn, Reference Ginn2014; Hawkins et al., Reference Hawkins, Manzi and Ojeda2014; Bozzon et al., Reference Bozzon, Murgia, Poggio and Rapetti2017, 2018; Hartung et al., Reference Hartung, Barnes, Welch, O'Flynn, Uptin and McMahon2017; Allmer, Reference Allmer2018; Chapman et al., Reference Chapman, Bicca-Marques, Calvignac-Spencer, Fan, Fashing and Gogarten2019; Richardson et al., Reference Richardson, Wardale and Lord2019). While these challenges are a cross-disciplinary phenomenon, the humanities are particularly threatened in terms of funding and perceived value (Nussbaum, Reference Nussbaum2010; Di Leo, Reference Di Leo2020).

The increasing precarity of academic work is a trajectory already followed by many other sectors of the global economy. While it is important to acknowledge the relative good fortune and opportunities of the average European academic compared to many scholars working in the Global South, resisting growing employment instability involves building solidarity across all sectors globally. Increasing economic precarity hurts everyone. The ECA community is committed to finding shared solutions to resist the effects and causes of this precarity both within and without archaeology and encouraging ECRs to have a voice in their own futures.

COVID-19

Our survey and others have begun to explore the initial impact of COVID-19 on ECRs. Although some report that the normalization of working from home has helped their work–life balance, most respondents raised concerns about further funding losses, less access to resources and workspaces, delayed data collection, loss of childcare arrangements, and deteriorating mental health, in addition to the general uncertainty, illness, and loss brought by the pandemic (Byrom, Reference Byrom2020; Hoggarth et al., Reference Hoggarth, Batty, Bondura, Creamer, Ebert and Green-Mink2021; Jackman et al., Reference Jackman, Sanderson, Haughey, Brett, White and Zile2021). Within archaeology, the pandemic has resulted in temporary closures of museums, cancellation of fieldwork, and ongoing uncertainty in the higher education sector (Kieffer, Reference Kieffer2021).

The pandemic is also accentuating existent inequalities in academia (Pereira, 2021). The first few months of the pandemic saw a disproportionate drop-off in publication preprint frequency among women (Viglione, Reference Viglione2020). With remote work and remote schooling, women tended to shoulder more childrearing and overall care responsibilities (Staniscuaski et al., Reference Staniscuaski, Reichert, Werneck, de Oliveira, Mello-Carpes and Soletti2020; Pereira, 2021). As women tend to have more teaching, marking, administration, and pastoral obligations (Stringer et al., Reference Stringer, Smith, Spronken-Smith and Wilson2018), the extra labour involved in the switch to online teaching and supervision has also disproportionately affected women academics (Viglione, Reference Viglione2020). In archaeology, recent surveys found the pandemic has worsened confidence in the future of the discipline (Mate & Ulm, Reference Mate and Ulm2021), and has significantly affected women, minorities, and ECRs, leaving these groups with a heavier workload, economically worse-off, and pessimistic about their future employment prospects (Hoggarth et al., Reference Hoggarth, Batty, Bondura, Creamer, Ebert and Green-Mink2021).

Positivity to confront instability

Despite the bleak conditions experienced, many ECRs remain hopeful and are driven by love for their respective fields (Christian et al., Reference Christian, Johnstone, Larkins, Wright and Doran2021). As in the present survey, other recent surveys of ECRs found most still wish to remain in academia (Aarnikoivu et al., Reference Aarnikoivu, Nokkala, Siekkinen, Kuoppala and Pekkola2019; Woolston, Reference Woolston2019). Seeking to resist the individualistic competition of the neoliberal university sector, many point to the collegiality of academic life, the spirit of collaboration, the positives of flexibility, and the excitement at the pursuit of knowledge (Barcan, Reference Barcan2013; Hawkins et al., Reference Hawkins, Manzi and Ojeda2014; Evans & Reid, Reference Evans and Reid2015; Hartung et al., Reference Hartung, Barnes, Welch, O'Flynn, Uptin and McMahon2017; Richardson et al., Reference Richardson, Wardale and Lord2019). These studies predate the pandemic, which worsened perceptions of future career prospects (Hoggarth et al., Reference Hoggarth, Batty, Bondura, Creamer, Ebert and Green-Mink2021; Mate & Ulm, Reference Mate and Ulm2021), but our results hint at ongoing optimism and enthusiasm in the discipline.

Thankfully, well-established academic colleagues and universities are taking proactive steps to combat aspects of this precarity. Some provide helpful tips to early career researchers navigating the competitive job landscape (Peters, Reference Peters2014; Fisher & James, Reference Fisher and James2022), and others offer concrete policy solutions (Bradfield, Reference Bradfield2016; McDonald, Reference McDonald2017; Atkinson et al., Reference Atkinson, Bardgett, Budd, Finn, Kissane and Qureshi2018; Bozzon et al., Reference Bozzon, Murgia, Poggio, Murgia and Poggio2018; Holzinger et al., Reference Holzinger, Schiffbänker, Reidl, Hafellner, Streicher, Murgia and Poggio2018; Fotta et al., Reference Fotta, Ivancheva and Pernes2020; Hoggarth et al., Reference Hoggarth, Batty, Bondura, Creamer, Ebert and Green-Mink2021; Mate & Ulm, Reference Mate and Ulm2021; Voss, Reference Voss2021a, Reference Voss2021b). The ECA community is already publishing interviews with tenured archaeologists geared towards providing insights into the different paths leading to a less precarious academic career (Brami et al., Reference Brami, Emra, Kolář, Malagó, Milić and Muller2020).

Staying positive in the context of precarious employment, lost opportunities, bullying, and discrimination is difficult. Yet many of the respondents to this survey remained passionate about their work, expressing a strong desire to remain in academia, and offered proactive suggestions and solutions. While the ECA community alone is unable to address the root causes of the job crisis in archaeology, which reflect broader trends in the economy and a shift away from the humanities, we are committed to finding solutions that ensure a level playing field and transparent practices. Our goal is for all ECRs to have the same academic opportunities and feel part of a larger scientific community. With this survey, we intend to highlight not just the problems and difficulties faced by ECRs, but also their positive experiences. There is much to be thankful for as research archaeologists, and we hope that the ECA community can help make access to this research sphere more equitable.

The solutions listed below are not new or radical but, if implemented together, they will address some of the concerns identified in the survey. Our suggestions were elaborated from the long-form survey responses and several face-to-face meetings with ECA members since 2019. They should not be taken to represent anyone's view in particular, rather the results of collective and collaborative consultation. These include:

Governments, universities, research institutes, and funding agencies should implement clearer pathways to secure employment. Transitioning from post-doc to faculty member should be facilitated by international and/or European employment schemes with guaranteed tenure tracks.

Higher education institutions should recognize ECRs as professionals, in line with a core principle of the European Charter for Researchers: ‘all researchers engaged in a research career should be recognised as professionals and be treated accordingly. This should commence at the beginning of their careers, namely at postgraduate level, and should include all levels regardless of their classification at national level’ (European Commission, 2005: 16). Most higher education institutions in Europe have signed up to this charter, making it a matter of implementation.

Research periods, whether as a graduate student or as a post-doc on a contract of any length, should be counted as work experience regardless of professional status and integrated in calculations of salary level and seniority.

As professionals, ECRs should have representatives in work committees, unions, and decision-making bodies. Thankfully, this is already the case in some higher education institutions, but not all.

Universities and research institutes should educate ECRs about their workplace rights and what they can expect from their employment. They should be given clear information on support networks, union presence, the university's vision and mission statements, its legal employment obligations, and any local agreements regarding discrimination and equality, as well as health and safety and wellbeing in a transparent and accessible manner. Education about basic employment and equalities law, as well as arrangements specific to individual universities, is empowering; it also means that it is harder to isolate and intimidate ECRs, individually and collectively.

Universities and research institutes should give ECRs the same structured workplace and development pathways as permanent employees, including a formal induction, regular progress reviews, and conversations about ways to enhance their career prospects. ECRs should be entitled to continuing professional development and training opportunities that allow them to develop key skills to further their career prospects and enhance their employability.

Universities and research institutes should make clear from the beginning of employment the means and processes of reporting bullying and harassment in the workplace. An independent body should be established to monitor these issues and make recommendations to improve the protection of ECRs at an international or European level.

Academics at all levels should encourage a culture of openness, support, and transparency. Toxic workplaces do not develop overnight or by themselves; they are created by individuals and their actions, and can be challenged and broken down, as well as rebuilt by the action of individuals.

Project directors should sign a memorandum of understanding with ECRs in advance of their involvement in fieldwork and laboratory work, ensuring that access to data and acknowledgements of work are clearly laid out from the beginning and available to everyone, following fair and transparent practices.

Teaching opportunities should be made available to all ECRs.

Publishers and granting agencies should encourage greater involvement of ECRs in the peer-review process. There should be no article processing charges for ECRs without Open Access funding.

Support and mentoring opportunities should be encouraged. The ECA community has already launched its own mentoring scheme (https://ecarchaeologists.com/mentoring/), but we would encourage international organizations such as the EAA to set up complementary schemes to build stronger intergenerational solidarity networks.

Archaeological associations should waive or significantly reduce conference and association membership fees, especially for unemployed archaeologists, those not reimbursed by their institutions, and those from lower income countries.

Conclusion

While this pilot survey has highlighted the precarious future for ECRs, given the choice, more than 71 per cent of ECRs who took the survey reported wanting to remain in academia. This, despite the unfavourable long-term and stable career opportunities, highlights their passion and dedication to the field. This should be encouraged by research institutions, higher education facilities, and funding agencies. Archaeology, and academia in general, would greatly benefit from giving the majority the choice to stay, not taking it away from them.

Acknowledgements

The first four authors contributed equally as co-lead authors. We are grateful to the EAA President and to the Executive Board for their support in establishing the Early Career Archaeologists (ECA) community. We also sincerely thank Catherine Frieman, Madeleine Hummler, and the two anonymous reviewers whose feedback greatly improved the manuscript. Our thanks go to Sarah McBride, who helped to set up the survey, and to Laura Coltofean-Arizancu, Michael D'Aprix, Jan Kolář, and Jesper de Raad for helpful discussions. This research would not have been possible without the participation of all respondents. We thank them for their time and wish them luck with their careers. The ECA community can be contacted via email: ecataskforce@outlook.com. M.B. was supported at the time of writing by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, Temporary Position for Principal Investigator [n° 466680522]. B.P.-B. was supported by the ERC Advanced project 788616: The Yamnaya Impact on Prehistoric Europe (YMPACT). B.I. was supported at the time of writing by a DAI-ANAMED post-doctoral fellowship. B.M. was supported by the grants of Türkiye Scholarships and Austrian Science Fund.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/eaa.2022.41.