Of all millennials, 86% identify with a political party, skewing more Democratic (51%) than Republican (35%) (Pew Research Center 2015). The fact that students actively attach partisan labels to their political beliefs poses problems in the American political science classroom. When instructors teach American politics, particularly about citizen political behavior, we ask students to acknowledge that individuals perceive and respond differently to politics. Although students—and the voting population at large—appear on the surface to understand the “fact” that individuals perceive and respond differently to the political world, they often struggle to recognize the assumptions or value priorities that underlie their own perceptions and responses. Liberal students, for example, express disbelief that an unemployed woman in Mississippi would identify strongly with the Republican Party. Why would a person who would likely benefit from certain government programs choose to vote for a party that opposes them?

Students’ inability to understand how fellow citizens construct political judgments that differ from their own poses a substantial pedagogical and practical problem. This lack of understanding signals a lack of empathy or an ability “to experience the values, feelings, and perceptions of another” (Stover Reference Stover2005), an important component of constructive political discussion and decision making.

Technology offers instructors a new method of encouraging the development of political empathy among students, particularly during election years when politics becomes more salient to the average American. As part of an assignment that required students to learn how to manage and present content with WordPress, a free website-development platform, I asked students to design campaign websites for political candidates of the opposite party. After completing the assignment, students demonstrated the ability to understand how people came to accept and justify political beliefs differing from their own. They also demonstrated a greater understanding of why their assigned candidate would appeal to voters.

Perhaps as important for the students, the assignment assisted them in learning how to design websites, a valuable skill in the job market. Faculty, especially those at liberal arts universities or those teaching in disciplines not considered “pre-professional,” often feel substantial pressure to cultivate “hard” career skills that can be readily defined and measured at the expense of “soft” skills (e.g., empathy). Incorporating technology into the political science classroom offers instructors an opportunity to facilitate simultaneously the development of hard and soft skills while motivating students to excel in their assignments by demonstrating their real-world applicability.

Incorporating technology into the political science classroom offers instructors an opportunity to facilitate simultaneously the development of hard and soft skills while motivating students to excel in their assignments by demonstrating their real-world applicability.

USING TECHNOLOGY TO FOSTER POLITICAL EMPATHY

Democratic theorists argue that individuals’ exposure to different political beliefs provides an important foundation for a well-functioning democracy (Arendt Reference Arendt1968; Aristotle Reference Reeve1998; Habermas Reference Habermas1989; Mill Reference Mill1956). Aristotle (Reference Reeve1998) and Mill (Reference Mill1956) believed that legitimate political decisions emerge only when public debate is vigorous and involves diverse political perspectives. Although these democratic theorists give a central role to political discussion among individuals with political differences, it is not merely exposure to different opinions that provides the mechanism for healthy deliberative politics. Each theorist demands that individuals exhibit an understanding of how other people think or feel about politics. Arendt (1968, 241) argued for “enlarged mentality,” which requires that individuals form an opinion after “considering a given issue from different viewpoints.” Deliberation among individuals with varied opinions “teaches citizens to see things they had previously overlooked, including the views of others” (Manin Reference Manin1987, 351) and allows one to reflect on the accuracy of their own beliefs (Habermas Reference Habermas1989; Mill Reference Mill1956).

This type of political deliberation requires individuals who possess empathy. However, empathy regarding political beliefs remains a difficult capacity to develop. For instance, partisans interpret facts based on the preexisting positions of their respective parties (Gaines et al. 2007). Individuals also appear to retroactively construct rational explanations in support of political positions that, in actuality, are largely formed by visceral and unconscious responses (Haidt Reference Haidt2012; Hibbing et al. Reference Hibbing, Smith and Alford2014). For instructors preparing students to be “good” democratic citizens, in part by expanding their students’ understanding of how individuals come to hold different beliefs, this presents a problem: How do we help students to develop greater political empathy?

Technology may assist instructors in fostering political empathy among students, while also providing a tool that can assess their understanding of course content. Reaching students through the digital and social-media platforms that they frequently use increasingly appeals to both instructors and administrators. Pedagogical studies indicate that instructors can use social media and other technologies to enhance student learning experiences (Damron and Mott Reference Damron and Mott2005) and to help students achieve classroom goals (Lawrence and Dion Reference Lawrence and Dion2010).

Open-source website-creation tools such as WordPress provide a powerful and underutilized tool to aid in the development of empathy.Footnote 1 WordPress has been used traditionally by instructors as a blogging platform (Lawrence and Dion Reference Lawrence and Dion2010; Quesenberry Saewitz, and Kantrowitz 2014). However, because blogging usually involves individuals sharing their own perceptions and responses to an audience, it does not force them to engage actively with different ideas. By asking students to use WordPress to create persuasive content in support of viewpoints that differ from their own, teachers force students to consider the perspective of another to construct compelling justifications in support of political views with which they disagree. Students thus learn how different people perceive and understand the political world, which may help them express a greater degree of empathy and respect for different viewpoints.

By asking students to use WordPress to create persuasive content in support of viewpoints that differ from their own, teachers force students to consider the perspective of another to construct compelling justifications in support of political views with which they disagree. Students thus learn how different people perceive and understand the political world, which may help them express a greater degree of empathy and respect for different viewpoints.

CANDIDATE WEBSITE PROJECT DESIGN

As part of a course entitled “Political Behavior in the American Electorate,” students were asked to complete a two-part project.Footnote 2 The first part required each student to construct a campaign website for a 2016 Republican presidential candidate using WordPress, a popular online content-management system. They were instructed to use information about political behavior that the class covered over the course of the semester—particularly how citizens make judgments about politics—in constructing this website. (Course content drew heavily from the political communication and psychology literatures, providing students ample information on how citizens form political judgments and what factors influence their formation.) The second part required students to write an eight- to 10-page paper explaining their content and design choices when completing their website using material covered throughout the course to support their arguments.Footnote 3 Students were advised to pay attention to the audience that they were trying to reach, the issues and character traits important to that audience, and the ideas and images that would be most appealing to that audience.Footnote 4

The students in this course had no previous training in web design and received minimal instruction in using WordPress.Footnote 5 The assignment comprised 25% of the final grade: 15% for the website and 10% for the accompanying paper. The project was designed as a course enhancement that would require approximately 45 hours outside of class to complete.Footnote 6

I randomly assigned candidates to the nine students in the courseFootnote 7 using Republican candidates because they either leaned toward or identified strongly as liberal.Footnote 8 This assignment procedure forced liberal students to engage with Republican ideas and positions, which would be the toughest test of their ability to empathize and understand opposing party viewpoints.Footnote 9

I designated one 75-minute class as an instructional seminar on using WordPress.Footnote 10 During this class, I helped students to create a URL,Footnote 11 demonstrated how to work with WordPress templates, and answered additional questions. We discussed design characteristics that, based on students’ experiences, made for good and easy-to-use versus bad or confusing websites. In the syllabus, I also assigned a textbook about website design in WordPress as required reading to supplement classroom instruction.

Before distributing the project instructions, I administered a survey to each student. They were asked to assess how qualified each candidate was to hold executive office and how likely each candidate was to win the Republican nomination.Footnote 12 After the students spent a semester researching and constructing arguments in support of their candidate on websites, I again asked them to assess their beliefs about each candidate’s competence and the likelihood that he or she would win the nomination.Footnote 13 In addition, I asked students to compare how they felt about their candidate and their candidates’ political beliefs at the end of the semester relative to the beginning. Quantitative and qualitative results provided evidence that technology-based assignments aimed at developing soft skills may help instructors to assess content in the political science classroom, while also motivating students to learn and apply that content.

RESULTS

The students’ websites varied in quality and sophistication. Those who completed the project sought facts about their candidates, their backgrounds, and their policy positions. Although some students spent much less time formatting and making their websites aesthetically pleasing, all demonstrated the ability to organize content, incorporate extensions such as Twitter feeds or stores, and publish content in the selected WordPress templates.

Students’ papers also demonstrated the ability to apply political-behavior theories and findings to tailor campaign communications for their candidates. However, not all of the students exhibited the same degree of fluency in doing so. For instance, one student emphasized some accomplishments by their candidate without identifying the intended audience or why the selected accomplishments were important. In contrast, other students emphasized policy positions that they viewed as relevant to voting blocs critical to their candidates or that they understood to be important to the general American electorate. For example, the student completing a website for Marco Rubio noted that she chose to emphasize issues (e.g., the national debt) that traditionally appeal to moderate and conservative voters. Another student included information about the spouse of the assigned candidate, noting that highlighting her accomplishments may appeal to female voters.

Three themes emerged from the data collectedFootnote 14: (1) students perceived themselves to have learned about their candidate; (2) they felt more favorable about the candidate; and (3) they felt that they had acquired a professional skill that would be useful in the future.

After completing the assignment, students believed that they knew more about their respective candidates and felt more positively toward them. The student who designed the website for Marco Rubio wrote, “I didn’t know as much about Marco Rubio in September, and I appreciate him more now after having done all of this research. I think he might be my favorite GOP candidate.” The student who created a website for Rand Paul wrote, “I can concede that I do feel slightly more inclined to trust in some of his proposals.” Yet another student concluded that, after building the site, they now “knew a lot more about Carly Fiorina, even enough to like her.” The student who created a website for Donald Trump noted afterward that “I have more respect for Trump,” although the student still “hated” what the candidate stood for politically.Footnote 15

Three themes emerged from the data collected: (1) students perceived themselves to have learned about their candidate; (2) they felt more favorable about the candidate; and (3) they felt that they had acquired a professional skill that would be useful in the future.

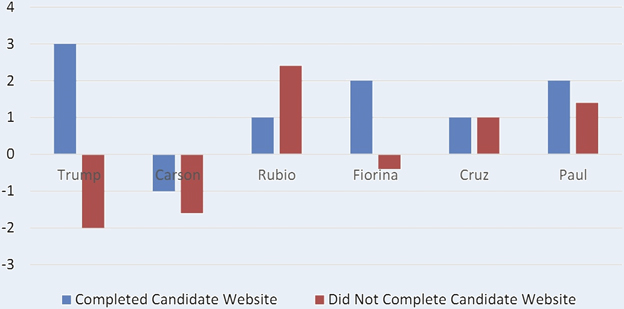

Comparisons of changes in student evaluations of the candidates across the semester provided quantitative data that mirror the qualitative data. All but one student assessed their candidate as being more competent after completing the assignment (figure 1).Footnote 16 The exceptional case was the student assigned to Ben Carson, who made a number of public mistakes during the spring of 2016 and had withdrawn from the race by the time the website was completed. It is interesting that the student completing the website for him judged Carson’s competence less harshly over the course of the semester than his classmates. Although Carson’s evaluation dipped about 1.5 points for students doing websites for other candidates, it dipped only 1 point for the student completing his website.

Figure 1 Difference between Posttest and Pretest Evaluations of Candidate Competence

In some instances, the difference between the student completing a website for a candidate and students completing a website for other candidates appear substantial. The student who designed a website for Donald Trump increased his evaluation of Trump’s competence by three points, whereas that student’s classmates decreased their evaluation of Trump’s competence by two points. During the semester, the class’s evaluation of Carly Fiorina decreased by a half-point. The evaluation of the student completing a website for her increased by two points during the same period.

Another theme that emerged across open-ended questions was that students believed that they had acquired a professional skill that would be beneficial on their resumés. They identified the project as “unique” and “fun.” Students admitted that the assignment, at times, was “frustrating.” However, they felt that the assignment was more “useful” and “relevant” than “normal school assignments.” One student identified the inclusion of assignments that involved building professional skills as a “marketing point” for a political science major and noted that refining these skills was the “point of attending college.”

After completing the assignment, one student asked to see feedback for his website during semester break because he wanted to address any critiques before including the website address in his job materials. Another student followed up two months after the class had ended to let me know that she had found a job building a website for a local business. Later, the same student used her new WordPress skills to share her experiences as a paid research assistant for a project at a nearby research university.

Much of the frustration experienced by students completing the assignment resulted from early difficulties navigating WordPress and formatting content. The students felt comfortable using WordPress after a few hours practicing with the web-development tool. Many also noted in class that discussion boards and forums about WordPress were more helpful than the book assigned on the topic.

Upon completing the course, the students also offered suggestions to improve the assignment, which I will incorporate into future iterations. Most had worked in informal groups along with their peers outside of class. However, many believed that such groups would function better within the classroom and expressed a desire for more class time to work on this assignment. In addition, students wanted more material on political marketing to be incorporated into the course. Future iterations of this course will include more readings on how candidates and campaigns reach out and try to persuade voters.

USING WORDPRESS TO BUILD EMPATHY IN THE POLITICAL SCIENCE CLASSROOM

Instructors teaching political behavior or American politics face a substantial hurdle. Citizens perceive and respond differently to politics (Haidt Reference Haidt2012; Hibbing et al. Reference Hibbing, Smith and Alford2014)—a reality that we seek to teach our students. However, students’ own party identification often impedes their understanding of this reality. In particular, students struggle to understand how others may perceive the same political phenomenon in fundamentally different ways. For those of us seeking to teach students not only content but also basic skills necessary for “good” democratic citizenship, this lack of political empathy poses a problem. Without the ability to hear and understand the other side, our political communities lack the quality of a discursive climate necessary for a well-functioning democracy (for a review, see Mutz Reference Mutz2006). This article demonstrates that technology-based assignments may help instructors overcome this pedagogical problem.

The use of technology in the political science classroom has grown along with scholarship demonstrating that such changes can enhance student experiences (Damron and Mott Reference Damron and Mott2005) and help instructors to achieve their student-learning outcomes (Lawrence and Dion Reference Lawrence and Dion2010).

This article indicates that technology fosters a greater empathy for opposing viewpoints. After completing an assignment that required students to construct a campaign website for a candidate with different views and to explain the rationale behind their website content, they displayed a greater level of confidence in the competence of those candidates and a greater awareness of their appealing attributes. As important for instructors trying to motivate their students to engage with course material (Jones Reference Jones2009), students expressed a belief that the assignment provided a professional skill that they would use in the future, which they argued made the assignment more enjoyable and engaging.

This website assignment can be modified in a number of ways to fit better with other political science topics. For instance, courses focusing on public administration or policy could ask students to create websites for policy proposals. Political-communication courses could require students to create a website archiving press releases that they write. Campaign courses could require that students write policy platforms or speeches for political candidates or parties to include on websites created for the class. Each proposed assignment provides an example of how technology may be used in the political science classroom to facilitate student engagement while also helping the instructor to gauge students’ ability to apply content to contemporary events and providing them with a marketable skill. In doing so, this expands the instructor’s repertoire of ways to utilize technology in the classroom in a manner that successfully prepares students for the political and professional world.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096518000082