Introduction

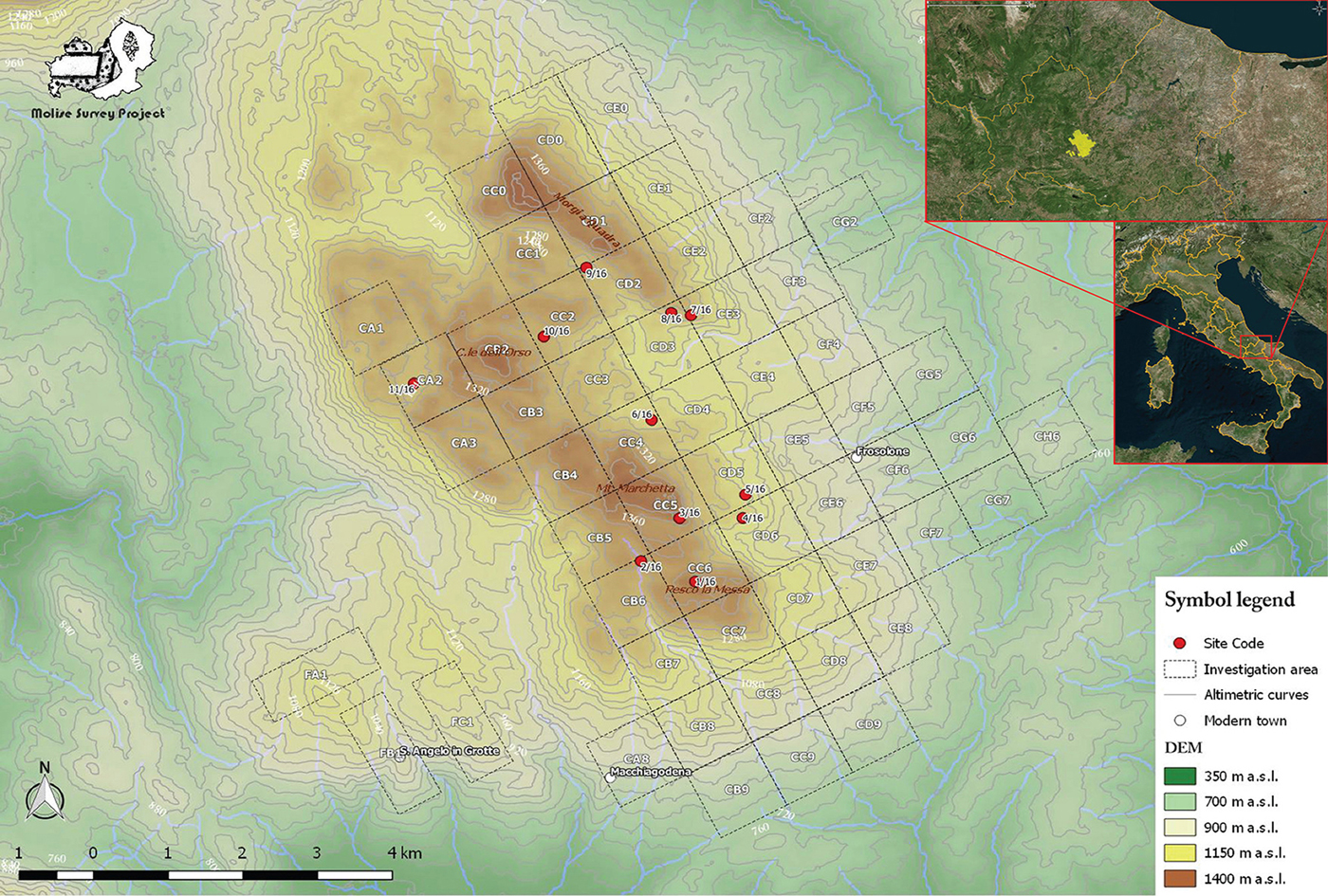

In 2016, the Molise Soprintendenza Archeologia, Belle Arti e Paesaggio (SABAP) granted a permit for the archaeological survey of a ~60km2 area that includes some of the highest mountains of the Molise region of southern Italy (Figure 1). Building on previous research (Barker Reference Barker1995; Minelli & Peretto Reference Minelli and Peretto2006), the main objective of the ‘Molise Survey Project’ is to investigate pre- and proto-historic human occupation of this upland area, with a particular focus on an ethnographical approach.

Figure 1. Map of the study area. Bronze Age sites: 1/16, 7/16, 8/16; Middle Palaeolithic sites: 2/16, 6/16, 9/16, 10/16, 11/16 (map by Enrico Lucci).

Located approximately 15km east of Isernia, this previously unstudied area is characterised by a pronounced physiography, with rocky spurs that reach 1400m asl, deep valleys and small lake basins subject to seasonal variation in water level (Figure 1). Mountain ridges, which represent the majority of the area under examination, are characterised by grassland vegetation; the mountain slopes are covered with woodland. Historically, the economic livelihoods of local communities were based on the exploitation of the available resources—water, grassland and agricultural soils—which were especially suited to transhumant pastoralism and the breeding of sheep, goat and cattle. Testimony to these pastoralist activities is found in the many stone structures, disused and ruined, scattered throughout the territory (Figure 2). Over the last 15 years, hundreds of wind turbines have been installed across the area, threatening the archaeological landscape.

Figure 2. Example of a pastoralist structure (photograph by the Molise Survey Project Archive).

Prehistoric presences at high altitude

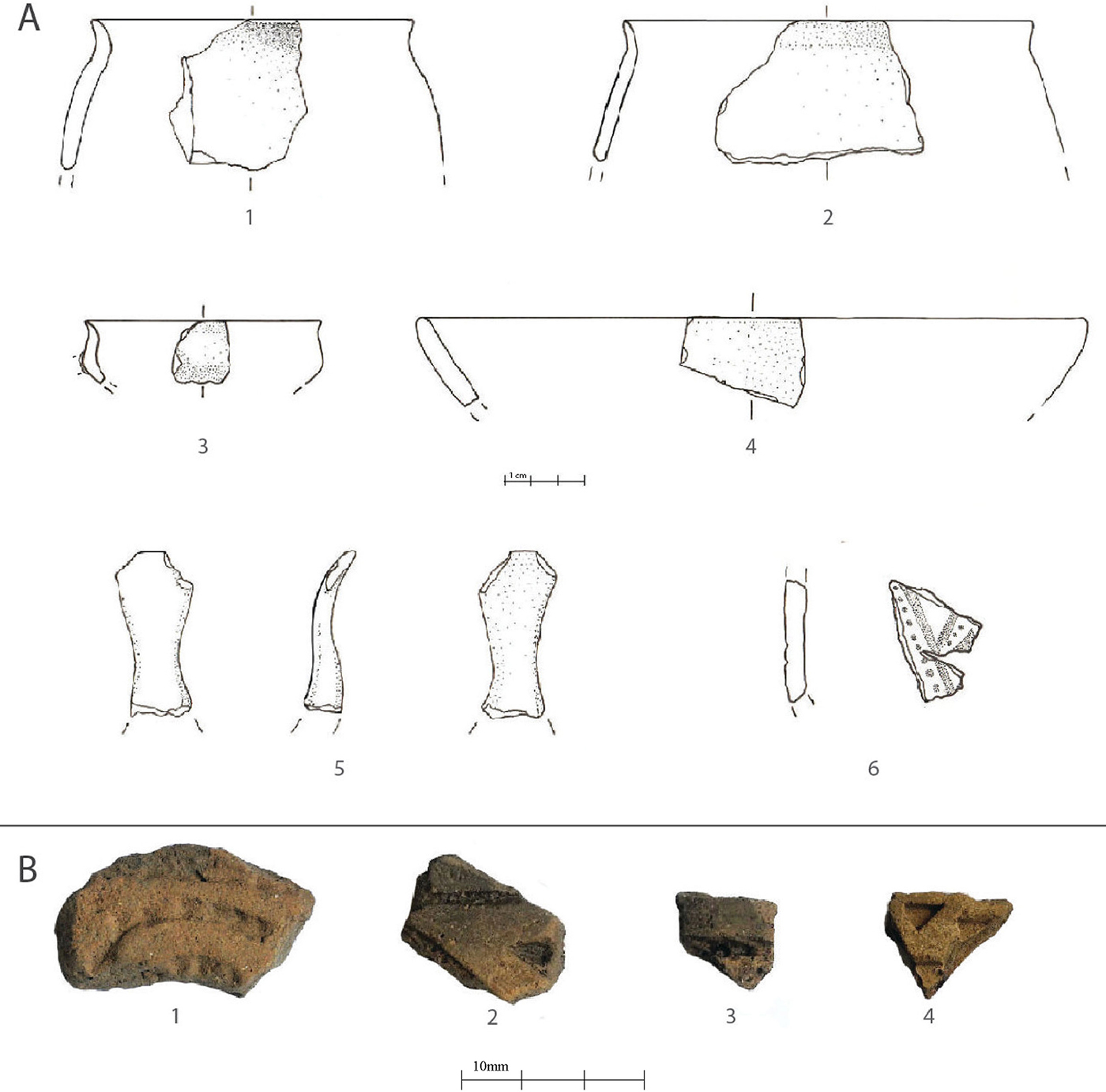

Our first surveys have focused on the highest elevations—territory over 1000m asl—with particular attention given to the rocky spurs and small lake basins (Figure 3). A large number of lithic artefacts, mostly from the shores of the lakes (Figure 1), relate to the Middle (Figure 4) and Upper (Figure 4.10) Palaeolithic. Two isolated lithic artefacts may relate to Neolithic and/or Copper Age activity (Figure 4.11–12). On the rocky spur of Pesco la Messa (Figure 1: 1/16), two arrowheads (Figure 4.13) and a huge number of potsherds were discovered (Figure 5A: 1–4, 6; Figure 5B: 2–4); these are attributable to the Bronze Age, particularly to the mid second millennium BC, although the raised handle (Protoappenninic) type (Figure 5A: 5) probably relates to the first half of the second millennium BC. Just over 3.5km north of Pesco la Messa stands the rocky spur of Morgia Quadra (Figure 1: 7/16 & 8/16). Several sherds of pottery have also been found at this location, including decorated fragments (Figure 5B: 1) attributable to the Middle Bronze Age (the mid second millennium BC). Due to the high concentration of items at several sites, the artefacts were collected using a sample area inside a grid composed of units of 1m2 (Figure 6). Taking into account previously proposed interpretative models (Puglisi Reference Puglisi1959), no other Bronze Age sites of central-southern Italy are known with these geomorphological characteristics. Thus, these sites provide new data about the exploitation and occupation of the Apennine Mountains during this period.

Figure 3. The highland landscape under investigation (photograph by the Molise Survey Project Archive).

Figure 4. 1–4 & 6) Mousterian industries from 11/16; 5) Levallois flake, sporadic; 7) undifferentiated core from 11/16; 8) blade-core rejuvenation from 6/16; 9) blade-core rejuvenation from 2/16; 10) blade fragment from 2/16; 11) Neolithic blade from 1/16; 12) Neolithic/Copper Age arrowhead from 3/16; 13) Bronze Age arrowhead from 1/16 (photograph by the Molise Survey Project Archive).

Figure 5. A1–2) jars from 1/16; A3–4) bowls from 1/16; A5) raised handle from 1/16; A6) decorated ceramic fragment from 1/16; B1) decorated ceramic fragment from 5/16; B2–4) decorated ceramic fragments from 1/16 (figure by the Molise Survey Project Archive).

Figure 6. View of sample collection area, Carpinone Lake—11/16 (photograph by the Molise Survey Project Archive).

Conclusions

The data collected during our initial fieldwork enriches our knowledge of prehistoric human activity in the Apennine Mountains. Future multidisciplinary work, including systematic excavation of Palaeolithic and Bronze Age sites, will further enhance understanding of the exploitation of these uplands and of human-environment relations across a wide chronological framework. The development of our scientific knowledge of the archaeological and ethnographic evidence of this region accompanies and supports the aim of local authorities to promote and protect this territory and the remains of its extraordinary cultural history.

Acknowledgements

We are extremely grateful to M. Moscoloni, G. Recchia, SABAP Molise, La Molisana S.P.A., the municipal administrations of Oratino and Frosolone and to the whole team of friends and young archaeologists who made this project possible.