When Jane Franklin arrived to inspect Robert Burford’s newly painted Summer and Winter Views of the Polar Regions in February 1850, she was joining the ranks of thousands of people who attended such visual events. As the nineteenth century progressed, visual culture became easier and cheaper to access, and spectacles such as panoramas sought to create an experience that offered more than simply viewing an engraving or a framed painting. The panorama placed the spectator at the centre of a circle, surrounded by a huge painting on a curved surface.1 These large 360-degree paintings became an international phenomenon, and many other visual spectacles evolved out of the original late eighteenth-century concept.2 By the mid-nineteenth century, the standard entry fee into a panorama had fallen to one shilling, with half-price entry for schools and children, making it an accessible experience across a broad spectrum of society.3

This chapter focuses on the large, and very popular, Arctic panorama Summer and Winter Views of the Polar Regions (1850), which opened in London shortly after the return of the first naval search expedition for Franklin, the voyage of 1848 to 1849 led by James Clark Ross. The panorama was exhibited at the Leicester Square rotunda, then run by Robert Burford, in February 1850. This respected establishment first introduced the concept of panoramas to London in 1793 and was seen as a venue of ‘instruction as well as entertainment’, which depicted places ‘so accurately that you may well suppose yourself transported thither’.4 By making extensive use of contemporary reviews, prints and sketches, and both published and unpublished written sources, I offer in-depth analysis of the content and reception of Summer and Winter Views.5 This panorama was based on the sketches of William Henry Browne, late lieutenant of the Ross expedition, and its reliable source was advertised repeatedly, with Browne even writing a letter (from an address in Liverpool) to The Times on the matter, thereby signalling its authenticity in comparison to ‘several exhibitions’ that were ‘purporting to show views of the Arctic and Polar Regions’.6 A concern with ‘truth’ and ‘accuracy’ pervades contemporary reviews of visual exhibitions like panoramas, and those that announced their origins from on-the-spot sketches reassured viewers that their contents were not deceptive. Reviewers’ preoccupation with the ‘truth’ and ‘reality’ confirms the power of Burford’s panorama to be regarded as a source of information, yet also belies a distrust of popular visual culture in general. Contemporary reviewers praised Summer and Winter Views for what they considered to be its realism and truthfulness, but simultaneously noted its ‘terrible and fantastic’ icebergs and its ‘supernatural aspects’, implying that such a place could not be real.7 However, as I will show, the Arctic represented in the panorama, thought to be ‘so very real’,8 was drastically different to that represented by Browne and to that conveyed in travel narratives and unpublished written records. Ultimately, Summer and Winter Views transported its viewers to a more sensationalistic and supernatural space that downplayed geography, domesticity, and reality, in favour of gothicised icescapes, masculine endeavour, and meteorological effects that combined to create a theatre for the moral sublime.

Summer and Winter Views formed part of a wider visual response to the early stage of the search expeditions, one that emerged through some of the many ‘public amusements’ produced for the Victorian urban-dweller.9 In London alone, a growing choice of large Arctic representations was simultaneously available to the public. In November 1849, a new play, The Sea Lion; or, the Frozen Ships and the Hermit of the Icebound Bay, had gone to ‘considerable expense in getting up the scenery’. This depicted several Arctic views, giving ‘a forcible idea of the horrors the brave explorers [on the Ross expedition] must have had to encounter’.10 By December, View of the Polar Regions was part of the new attractions at the Colosseum, Regent’s Park.11 At Minerva Hall, the Grand Moving Panorama of the Arctic Regions was among the Christmas exhibitions; it ‘combined the results of the principal Arctic navigators’, and its ‘faithful scenery’ was ‘authentically rendered from original drawings’.12 Summer and Winter Views opened in February 1850, and in March a series of dissolving views of the Arctic Regions ‘with an interesting description’ was exhibiting twice daily at the Royal Polytechnic Institution.13

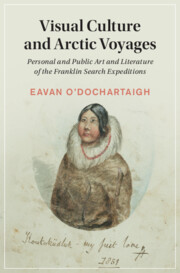

Until recently, this panorama, known mainly through an engraving in the descriptive booklet available at the exhibition (Figure 4.1), had not received any in-depth critical attention. Laurie Garrison notes that in the ‘current historical literature, any individual panorama usually only receives a few sentences or a few paragraphs of attention’.14 She addresses this by examining the ‘scientific and political context of the production, exhibition and reception’ of Summer and Winter Views.15 Garrison maintains that the Admiralty and the proprietor of the panorama collaborated to portray a version of the lately returned Arctic expedition that exonerated those involved, ‘having been unavoidably thwarted by the powers of nature’.16 This was, she argues, evident both in the content of the panorama, which emphasised the activities of expedition members, and in the text of the accompanying booklet that offered a ‘firm justification’ of the Ross expedition and the Admiralty.17 However, she notes that the panorama encouraged multiple responses, especially an emotional response, as evident by reviewers’ reactions, concluding that ‘multiple interpretations were at work, undermining any singular, hegemonic view’.18

Russell Potter briefly discusses Summer and Winter Views in the broader context of nineteenth-century Arctic spectacles, noting how Burford had ‘divided time and space in two’19 and surmising that this reflected the ‘curious doubleness of the northern sublime – a sublimity of chaotic action, lethal in one moment and picturesque the next’.20 Robert G. David deals with the panorama in his general survey of nineteenth-century British visual representation of the Arctic, arguing that Burford intentionally depicted both the sublime and the picturesque by dividing the Arctic into two halves.21

This chapter builds on the work of previous critics, offering a more art historical approach to the content of Summer and Winter Views, attending to primary visual sources and a wider range of written sources, noting in particular how certain aspects of the experience of expedition members were erased, replaced, or transformed to create a more supernatural, gothic, and masculine space.

The Panorama Summer and Winter Views of the Polar Regions (1850)

In 1793, Irishman Robert Barker opened a permanent exhibition centre for his panoramas in the form of a rotunda in Leicester Square, London, which continued in business for seventy years. He was succeeded by his son, Henry Aston Barker, in 1806 and eventually by Robert Burford, who had worked with them, in 1827.22 By the mid-nineteenth century, London was awash with visual experiences, so much so that Burford felt compelled to state ‘with the exception of one, it is the ONLY PANORAMA IN LONDON, though various other exhibitions, consisting merely of moving pictures, make use of the term Panorama’.23 In December 1849, the Athenaeum commented: ‘There is a perfect battle of B’s with new panoramas to catch the holiday people of London and the country visitors of this festive period of the year. We have Burford, Banvard, Brees and Bonomi, all catering successfully for the amusement and instruction of the public.’24 Such exhibitions were expected to be educational as well as entertaining, making their association with reality an important selling point. As Sadiah Qureshi points out, ‘pleasure and instruction were neither mutually exclusive nor necessarily confined to distinctly separate spaces’.25 The panoramas were thought of as ‘Animated Illustrations of Geography’ and were considered to be a ‘vehicle for instruction’ as well as ‘an illusion to the senses and a new luxury in aesthetical art’.26

The proprietors of the Leicester Square rotunda tended to emphasise the quality and accuracy of its painted images, as well as their educational value, over the showier imitators. They traditionally painted their panoramas based on their own on-the-spot drawings of places they had travelled to, while similar spectacles tended to employ dramatic lighting, moving props, and elaborate illusory effects in order to draw the crowds.27 Robert Burford and his assistant Henry Selous both exhibited paintings at the Royal Academy,28 and Burford felt it his ‘duty’ to emphasise that his panoramic views were not ‘a species of scene-painting, coloured in distemper, or other inferior manner’ but were ‘painted in the finest oil-colour and varnish … and in the same manner as a gallery picture’.29 Despite the competition, the original panorama, run by Burford from 1827 to 1863, was more valued by some. The art critic and theorist John Ruskin later expressed his feelings on the varying quality of panoramas: ‘Calame and that man – I forget his name – are merely vulgar and stupid panorama painters. The real old Burford’s work was worth a million of them.’30 He lamented the closure of Burford’s panorama in 1863, suggesting that it ‘ought to have been supported by the Government’.31 The closure was equally regretted by the writer of Leicester Square; Its Associations and Its Worthies (1875) who felt that it was ‘a real loss, ill-supplied by the ever-increasing swarm of picture exhibitions’.32 Around the time of the exhibition of Summer and Winter Views a writer for Musical World referred to Burford’s panoramas as ‘decidedly the highest works of their class, – where we contemplate Pompeii, the Arctic Regions, and the Lakes of Killarney’.33 The subject matter treated by the panorama encompassed scenes of battle, voyages of discovery, views of cities, localities of natural beauty, and public ceremonies.34 It was not only a ‘means of virtual travel’ but was also a ‘vector of news’, showing natural events and battles that celebrated ‘a sense of British military might and identity’.35

Burford’s panorama in Leicester Square was far more than an amusing spectacle. Ruskin considered it to be ‘an educational institution of the highest and purest value … one of the most beneficial school instruments in London’.36 Alexander von Humboldt believed that panoramas should be used to depict nature, and that if large panoramic buildings containing ‘a succession of such landscapes, belonging to different geographical latitudes and different zones of elevation, were erected in our cities and … thrown freely open to the people, it would be a powerful means of rendering the sublime grandeur of creation more widely known and felt’.37 Humboldt singled out Barker’s panoramas when talking about the improvement in landscape painting on a large scale, as being a ‘kind of substitute for wanderings in various climates’.38 A plate from an early nineteenth-century book39 shows a section of the Leicester Square rotunda with its panoramas and visitors, the majority of whom are women (often being guided by men), a reflection perhaps of their more geographically constrained role in nineteenth-century society.40

By the time Summer and Winter Views was exhibited, the rotunda at Leicester Square was three storeys high; the lowest and largest storey, which housed Summer and Winter Views, was approximately twenty-seven metres in diameter. The circular balustraded platform from which the polar panorama was viewed was approximately nine metres in diameter and the painting was always viewed from a distance of no less than nine metres.41 The layout was designed so that customers entered by a series of darkened stairs, emerging on a central viewing platform into an all-encompassing experience, where they had no frames or reference points to distract them from the illusion. The platform on which the spectators stood and observed the Arctic representation must have given them the feeling of standing on the deck of the ship, or even up in the crow’s nest; the visual impact of Burford and Selous’s representation of the Arctic should not be under-estimated. Viewing their panorama provided an experience for the Victorian senses far beyond that evoked by reading a newspaper or narrative, attending a lecture or viewing a single framed painting in a gallery. The panorama eliminated the frame of a picture that people were used to seeing, as well as removing any reference points of size and distance outside the painting,42 leading Humboldt to describe the spectator of the fixed panorama as ‘enclosed as in a magic circle and withdrawn from all disturbing realities’.43

Although it is not known how many people visited Summer and Winter Views, such exhibitions were enormously popular in London at the time. On 26 December 1849, 19,986 people visited the British Museum, and the Colosseum, where the Dansons’ View of the Polar Regions was then exhibiting, received ‘an immense number of visitors on the same day’.44 Madame Tussaud’s was so ‘densely crowded from morning to night’ on the same day that it was necessary to have ‘additional police-constables on duty in the street to prevent accidents’.45 Given that Summer and Winter Views received numerous favourable reviews and Burford’s establishment was highly regarded and widely known, it is likely that very large numbers of people visited during the fourteen months for which it ran.46 The private viewing of Summer and Winter Views, which Jane Franklin attended, on 9 February 1850 (prior to the public opening) was crowded and included the Lords of the Admiralty among the earliest guests.47 Two months after the opening, the Critic noted that it continued ‘to attract delighted crowds’.48 Nine months after it had opened, it was still making an impression, with the Critic declaring that it was a scene ‘never to be forgotten’.49

Reviewers noted the panorama’s artistic qualities, but even more important seems to have been the assumption of its truth value for some spectators, or how closely it mimicked the ‘reality’ of the Arctic, a place that viewers would never be able to go to in order to verify the representation. Although Burford and Selous often drew from life themselves, by obtaining Browne’s sketches from the Admiralty, they had secured the next best thing, a first-hand eyewitness account.50 The display of furs on the viewing platform, as well as drawings by Browne, was a calculated move to bolster the panorama’s authenticity.51 The numbered key under the engraving of the panorama in the printed booklet (see Figure 4.1) also implied that the panorama was a factual record. But beyond ordinary pictures, Humboldt had noticed the immersive quality of the panorama that caused ‘impressions’ to mingle with ‘remembrances of natural scenes’.52 The all-encompassing panoramas became part of spectators’ memories, both of people who would never go to the Arctic and of future expedition members, like William Parker Snow, who, when he did get to the Arctic six months later, ‘almost, fancied that [he] was again in London viewing the artistic sketch’.53 However, the power of the panorama to immerse the viewer in ‘reality’ also caused an anxiety around its purpose of deceiving the spectator. In 1849, Professor Charles Robert Leslie gave a lecture on painting at the Royal Academy where he asked ‘whether others have not felt what has always occurred to me in looking at a Panorama, that exactly in the degree in which the eye is deceived, the stillness of the figures and the silence of the place produces a strange and somewhat unpleasant effect’.54 Leslie felt that there was always something ‘unpleasant—in all Art, of every kind, of which deception is an object. We do not like to be cheated.’55 Indeed, as Nigel Leask observes, it could be thought of as a ‘sort of troubling early nineteenth-century version of “virtual reality”’.56

Some of the unreservedly positive reviewers of Summer and Winter Views were particularly drawn to what they considered to be its ‘truthful’ qualities, perhaps unconsciously trying to offset this unpleasantness that Leslie identified. The Athenaeum considered Summer and Winter Views to be ‘one of the most successful’ panoramas that they had seen.57 The Art Journal declared, ‘we have never witnessed more interesting pictures than the present, or any possessing greater novelties in effect … Altogether, we do not remember a more peculiarly truthful and artistically beautiful production exhibited by the talented proprietor.’58 The use of the term ‘witnessed’ here implies the reliability of an eyewitness account, while the phrase ‘peculiarly truthful’ suggests the uneasiness associated with deception. The Critic noted the difficulty of persuading oneself that it was not, in fact, reality: ‘It is so real that an effort is needed to abstract the mind from the scene in the picture to the reality.’59 As late as November 1850, the same periodical commented that Burford’s polar panorama was ‘a sublime scene, never to be forgotten, it is so very real’.60

A large part of the reviewers’ conviction of the panorama’s realism came from the fact that Summer and Winter Views was directly linked with scenes recorded by Browne during the Ross expedition of 1848 to 1849, a connection that was reiterated in reviews and advertisements. The Era reasoned that as Browne’s on-the-spot drawings had been ‘transferred by Mr. Burford to canvass [sic], the faithfulness of the scenery may therefore be depended on’.61 The Morning Chronicle noted that the panorama ‘professes to be a correct view’ and that the ‘effects’ were produced ‘without exaggeration or meretricious display’.62 The Observer reviewer went further, marvelling that, although Burford ‘had to labour under the disadvantage of pourtraying [sic] scenes which he himself had … never seen’, they were ‘assured by gentlemen who had wintered in these northern latitudes, that the resemblance of the panorama to the reality is perfect’.63 Unfortunately, we only have access to three rough sketches or paintings by Browne that reside in public archives from the Ross expedition. The ‘drawings’ displayed at the panorama, whose whereabouts, if they survive, are unknown, were likely to have been more finished versions of sketches done in the Arctic.

Considering that Browne’s visual art was the first body of work to be publicly produced from the Franklin search expeditions, remarkably little is known about his life compared to some of his contemporaries. For example, he fails to appear in the Dictionary of Irish Biography64 or in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.65 In view of the fact that his sketches inspired a panorama, likely to have been seen by tens of thousands, it is worth taking a closer look at his background. Although several sources record that Browne was from Dublin, William Henry James Browne was actually born in the village of Howth, County Dublin, c. 1823, where his father James Browne was the harbour master from 1818 to 1836.66 At the time, Howth was far from picturesque: in 1825, an anonymous letter to the Freeman’s Journal described a series of ‘disgusting’ views in the area, concluding that Howth was a ‘totally neglected village’ despite the large sums of money spent in the construction of its new harbour.67 Browne initially joined the merchant navy, but during the 1840s he served as midshipman on the Royal Navy surveying vessels, the Sulphur and the Samarang, both under the command of Captain Edward Belcher in the Pacific.68 His watercolours of coastal elevations from this period show great attention to detail, a delicacy of brushwork, and an interest in the work far beyond that required for the task.69 This earnest dedication to his visual practice is evident particularly in the carefully painted titles on these elevations, an attention to detail that was unnecessary, and unusual, in the production of navigational drawings.

In 1848, Browne was appointed as third lieutenant on the Enterprise, on the naval expedition led by James Clark Ross to search for Franklin in the region of the magnetic north pole. The eighteen-month-long expedition spent a winter in the ice pack at Port Leopold, Somerset Island, and the men suffered badly from inadequate provisions. Despite this, Browne must have been sketching regularly as, on his return to England, his visual records were transformed into a folio of lithographs, Ten Coloured Views70 (discussed further in Chapter 5), as well as Summer and Winter Views. Although Browne returned to the Arctic on the Resolute in May 1850, as part of the Austin expedition, none of his visual work from that voyage appears to have been re-used. During the winter, he painted the drop-scene for the theatre aboard ship and was praised for his talents in the on-board periodical.71 Eleven paintings and drawings by Browne from the Austin expedition exist in public archives.72

Transforming Geography: Regions and Landscapes

Despite its alleged realism, the panorama attempted to downplay the geographical aspects of the expedition in favour of creating more incredible spaces. As the booklet explained, it was divided into ‘two distinct subjects, one-half the great circle exhibiting the Polar seas at midnight in the summer season, the other presenting a similar scene at noon, under all the sublime severities of an arctic winter’.73 The accompanying booklet was available at the panorama at a cost of sixpence, and its sole illustration, a diagrammatic key (Figure 4.1), shows the content and layout of both halves of the vast painting. These two halves were separated by a partition (and possibly a curtain) on the viewing platform so that the views could be seen independently.

The title of the panorama, Summer and Winter Views of the Polar Regions, is the initial indication that geography will not take precedence here. The reader is placed firstly within seasons – times rather than places – and secondly within ‘Polar Regions’, a term so vague that it could apply to anywhere within the Arctic and Antarctic Circles, marking it out as a vast ill-defined realm to be traversed rather than lived in. The term ‘Polar’, more climatological than locational, is distinct from place names such as Spitsbergen or Boothia, which were included in titles of earlier Arctic panoramas at Leicester Square in 1820 and 1834. This title also contrasts with the titles of Burford’s other panoramas such as those of Sebastopol (1855), the Bernese Alps (1853), and Granada and the Alhambra (1854). Burford’s decision not to use a place-specific title becomes all the more significant considering the subject matter is highly geographical in nature. Unlike the expedition itself, the title does not locate us near Upernavik, Greenland, in summer or at the north-east tip of Somerset Island in winter, or even in the Arctic, but cultivates spatial uncertainty and, along with its composition, wishes to place the viewer in a time, rather than a place, into seasons, made distinctive by their light and dark variations. While the accompanying booklet mentioned geographical information, such as place names and coordinates, this was inundated by a sea of evocative description: ‘desolation’, ‘wild disorder’, and ‘dreary shores’ all combined in this ‘sublime and splendid exhibition of icy grandeur’.74

Certainly, the locational information provided was lost on Mr Booley, a fictitious character who gave an account of his travels by panorama in Dickens’s weekly journal Household Words. The adventurer, while mentioning Port Leopold, does not appear to be aware that a different location, over a thousand kilometres to the east, is represented in the summer view, or that the summer view was chronologically earlier than the winter:

Mr BOOLEY slowly glided on into the summer season. And now, at midnight, all was bright and shining … Masses of ice, floating hither and thither, menaced the hardy voyagers with destruction … But below those ships was clear sea-water, now; the fortifying walls were gone; … and the sails, bursting from the masts, like foliage … spread themselves to the wind, and wafted the travellers away.75

The summer view shows the expedition ‘in the month of July, in what was named Glacier Harbour, on the coast of Greenland, in latitude 73° 42′ N., longitude 55° 20′ W’.76 Here, Burford gives the coordinates, nominally conferring an attribute of place on Glacier Bay. But the scene lacks any sense of earthly location; there is no attachment conveyed where ‘all is wild disorder’ and ‘of which there exists no parallel’.77 The sharp, peaked icebergs jostling with the ships indicate that the theatrical drama overrides geography and science. Burford’s view has stretched the truth both visually and textually by creating a wildly romanticised world.

While the term ‘Polar Regions’ defines the space by climate rather than specific geographical places, the two halves of the panorama again mark the territory’s space by meteorological effect: light and darkness. By emphasising the peculiarities of the extreme latitudes, Burford converts the Arctic into a space that becomes easily associated with the Burkean sublime, which found its source in many factors such as ‘quick transitions from light to dark’.78 The extremes of light and dark depicted here are in reality separated by six months and, as some expedition members noted in their narratives or journals, the darkness of midwinter was an experience that one became accustomed to gradually during the preceding months of increasing darkness. In fact, some light is visible during the Arctic winter even when the sun is eighteen degrees below the horizon. A member of the subsequent Austin expedition in 1850 observed: ‘the daily decrease of light gradually habituates the mind to the unnatural change’.79 On passing his first Arctic winter in 1853, Edward Belcher noted: ‘This will close the month of January: not much unlike a gloomy English November, but not at all realizing the very cheerless long winter nights which have so frequently dinned our ears.’80 In Burford’s panorama, however, viewers stepped between summer and winter, light and dark, visually separated by a partition, in a matter of seconds.

Reviewers were particularly impressed with the representation of ice, particularly with its appearance in the summer scene, which showed the ‘awful majesty of the Polar seas at summer midnight’.81 The Art Journal noted the ‘extraordinary and fantastic forms assumed by the icebergs’.82 For the Literary Gazette, the icebergs were ‘terrible and fantastic’.83 The Observer noted that ‘No tree, or corn, or verdure of any kind is visible to the eye, even in the season of summer … Never did the eye of man gaze on a more sublime scene.’84 A reviewer in the Gentleman’s Magazine felt that both sides of the panorama exhibited ‘the fields of perpetual ice in their opposite aspects of the summer and winter seasons’.85

Burford’s text and painting worked together to create a threatening and formidable world where the expedition was pitted against the environment. The peaked icebergs of Burford’s summer view were in fact stylised and romanticised. His gothic renderings bore little resemblance to Browne’s sketches, despite reviewers having been convinced of their reality. The diagram below (Figure 4.2) shows the evolution of Browne’s painting through multiple media forms, from the rough painting he made in the Arctic through to the lithography, the panorama itself, and the accompanying booklet.

The small painted sketch Valley of the Glaciers, Greenland, measuring only 8.3 × 30.5 cm and signed with Browne’s initials, is dated to 1848 and, as will be explained below using topographical evidence, is almost certainly one early prototype for the summer half of Burford’s panorama.86 Valley of the Glaciers, Greenland (Figure 4.3) with its hastily laid-down wash and white gouache, was possibly painted on 20 July 1848, during the early part of the voyage, when an ‘immense glacier was here observed extending completely along the imaginary coast line, on a level with the steep and elevated land … The evening was cloudy but perfectly still.’87 An additional representation of the glacier appeared as a chromolithographed plate in the folio, Ten Coloured Views (1850), which was published as the panorama opened.

The alteration of geography by Burford is here seen clearly in an examination of both views together (Figure 4.1 (top) and Figure 4.3), which allows the similarities and the differences to become evident. The view of a large glacier meeting the sea and the unusual proportions of the watercolour picture are very close to those of the panorama diagram, lending further support to the claim for the panorama’s origin. Although the composition in both is broadly similar, Browne’s version appears to be taken from sea level while Burford’s panorama suggests a view seen from above. The numbers used in the key to identify significant points on the landscape and incidents lend the scene a layer of authenticity and imply accuracy. The ice may be the dominating feature of both compositions, but the nunataks88 are visible too, if to a much lesser extent in the panorama booklet. The two nunataks of the panorama (centre and right) are situated in the same part of the composition as the watercolour, further making the case for the argument that the panorama derived its information from the scene depicted by Browne. On the left-hand side of the panorama version, the missing nunatak has been replaced by a large iceberg that reaches far above the height of the glacier. The panorama makes considerably more of the ice and reduces the land. Browne’s rounded nunataks in the watercolour reassure the viewer of the presence of land, but the panorama loses this sense of stability, reducing the land to two comparatively small, jagged peaks rising above the glacier in the distance, as indicated in the booklet key. This minimising of land in the panorama further removes the viewer from the possibility of any solid, secure connection.

The lithograph Great Glacier, Near Uppernavik89 (Figure 4.4) emerges as another link in the chain of Arctic reiterations of a single scene, and it may also have derived from the expedition watercolour Valley of the Glaciers, Greenland or a similar composition by Browne.90 The lithograph is compositionally similar to the watercolour and panorama, again showing the face of the large glacier meeting the sea. Like the watercolour, the three nunatak summits are seen jutting out of the ice at the sides and in the centre of the glacier (left, centre, and right).

Taking the three images together, it is easy to see how the largest and most public depiction was the one that was farthest removed from its visual origins. From the expedition watercolour to the lithograph to the panorama, the ice grows from rounded, unthreatening forms in the earliest version into angular structures in the lithograph and finally, in the panorama booklet, to an extraordinary succession of Gothic structures that invoke the romantic sublime. The icy spires of the panorama pierce the horizon-line dramatically, their serrated forms erratic and restless, unlike the solid constant bulk of glacial ice represented in the watercolour. Not only that, but mirroring the spires on the left are the masts of the Enterprise likewise piercing the skyline (so tall that the mast-tops leave the page), suggesting that they are comparable opponents (this technique is repeated in the winter view to enable viewers to see the vast size of the ships).

The emphasis on the impressive nature of the ships, where icebergs and ships jostle for dominance, aligns with the language of conflict often used in describing the Arctic around the period of the Franklin searches. For example, a description of a visit to the ships of the Austin expedition, while docked at Woolwich in April 1850, described the Pioneer as a ‘floating fortress against the fierce assaults of the Giant Frost’ with enough stores to withstand the ‘beleaguering siege of – it may be – a two or three years’ Arctic winter’.91 An article on Arctic exploration in 1860 in the New Monthly Magazine, written when the fate of the Franklin expedition was known, opened with the metaphor of war: ‘The battle of the Arctic regions has been fought out and out again. On the one side is man, by nature weak, sensitive, and frail; on the other, privation, gloom, and cold, stern and ever-enduring.’92 In Browne’s watercolour the ships, while small and unobtrusive, provide a scale by which to gain some idea of the immensity of the glacier. Despite their small size, the ships do not appear to be in any danger.

The rounded masses of ice in Browne’s watercolour may dwarf the two ships but they are far removed from the Gothic icy pinnacles of Burford’s panorama, even as seen in the booklet, which was the schematic version of the original panorama. The text in Burford’s booklet heightened the intensity of the summer scene by using evocative language that includes the stock descriptors like ‘dreary’ and the Gothic ‘frowning’, which had become associated with the Arctic in the public imagination:

Desolation here reigns triumphant; all is wild disorder. The sea, piled into solid mountains of ice, strangely mingles its white pinnacles with the dark and frowning summits of rock that here and there rise to an immense height; and the earth, buried beneath its cumbrous load of frozen water, blends its dreary shores, undistinguishable by any boundaries, with the bleak deserts of the ocean.93

The description reads like the opening of a late eighteenth-century Gothic novel and conjures up a landscape of terror: a heavy, dark, and tumultuous world almost apocalyptic in nature in spite of the summer sun. The text also has echoes of the idea of a ‘geological apocalypse’ on the scale of Thomas Burnet’s late seventeenth-century Telluris Theoria Sacra (‘The Scared Theory of the Earth’), which imagined a huge deluge, a primordial drama, had caused the scars on what had once been a featureless globe.94 In the panorama, the sea, with its mountainous peaks of ice, replaces the mountains.

The winter portion further reconstructs the Arctic, removing the reader from geography and into a more sublime space; the booklet describes ‘two noble capes’ showing some ‘great convulsion of nature’ that look down with ‘dark frowning masses’. The descriptions of the mountains, violent, anthropomorphised, and disapproving, again recalling the seventeenth-century geological theories of Thomas Burnet, suggest turmoil and upheaval. ‘Around in every direction the distance is one interminable waste, and desolate region of eternal winter.’95 Simultaneously, the ‘great convulsion’ and the ‘eternal winter’ suggest both the beginning and the end of the world. The space is described in negative emotional terms, again invoking apocalyptic imagery, implying that here is a space of nothingness, which is alienating and incompatible with life. This vast region, then, is a non-place; it is ‘interminable’, tilting as far as one can imagine away from the sun, and out into space itself.

Enhancing Gender: Masculinity, Activity, and the Challenge of ‘Man versus Nature’

The Arctic of Burford and Selous is also an icescape peopled by ships’ crews. Although Inuit are not present, their absence is not necessarily misleading; the winter quarters of the Ross expedition were remote from Indigenous communities, and the large glacier depicted in the summer portion is around fifty kilometres inshore from the small island settlement of Upernavik. The figures we do see in the panorama are active and engaged in the outdoor pursuits of hunting, rowing, trapping, and building. These icescapes, populated by physically active figures, are in stark contrast to primary visual material from Browne, which often shows standing or seated figures in repose. The active bodies connect with the perception of the Arctic environment as ‘threatening and unstable, a place not for reflection but for action’.96

As Andrew Lambert notes, some agents were keen to play down the scientific work that was carried out on the searches, showing that this was a purely heroic mission to save their fellow countrymen and not an excuse to carry out scientific observations, to complete the Northwest Passage, or to lay claim to the territory.97 Garrison points out that these activities, which are found throughout the panorama, ‘may also have suggested indirectly that much activity was taking place in the Arctic. Much activity, that is, in search of Franklin, undermining suspicions that rescue attempts were simply being appended onto voyages whose real priority was to cross the Northwest Passage.’98 The active figures, labouring in the almost-theatrical spaces, also strongly suggest the ‘man versus nature’ trope. Kirsten Hvenegård-Lassen observes that the ‘humanity versus nature’ storyline performed in twenty-first-century scientific Arctic narratives includes ‘tropes associated with heroic polar explorer myths of the past’, such as ‘heroic endurance’ and the ‘human struggle for survival’.99 Indeed, one of characteristics of the colonial narrative of the Arctic is that ‘nature becomes an agent in the story’, and ‘man’s struggle against the elements’ is a key component of the narrative.100 Both halves of the panorama displayed overtly masculine activities associated with Arctic exploration, yet none of these activities is depicted in Browne’s extant work.

Although Burford’s depiction of the ships overwintering in Port Leopold, Somerset Island, or the Winter View, was derived from a sketch or painting that does not appear to survive,101 other visual sources linked to Browne’s primary visual depiction and to the panorama exist. The figure below explains the complexity of the visual sources, showing how Browne’s initial painting or sketch inspired an engraving, a lithograph, and a panorama (Figure 4.5). An engraving of the panorama was then made as a visual key, and a section of it was engraved for the Illustrated London News. The earliest representation to be published was an engraving captioned The Expedition Housed in for the Winter, which appeared in the Illustrated London News only five days after the ships returned (Figure 4.6).102 The accompanying article, which used three unattributed engravings to illustrate the news story, stated that they had been ‘fortunate enough to succeed in obtaining some Sketches of the scenes of peril to which Sir James Ross, has been exposed’.103 Although the engraving shares a subject matter and an aspect (or viewpoint) with the scene represented in the winter portion of the panorama, the former is unpopulated and sombre, very similar to a lithograph, Noon in Mid-Winter (Figure 4.7), which was published as part of the set Ten Coloured Views in February 1850. In Noon in Mid-Winter, however, three stationary figures inhabit the scene, and the use of colour allows the depiction of the sun below the horizon.

By contrast, the winter portion of the panorama, as shown in the booklet (Figure 4.1 (bottom)), presented a heavily peopled drama amidst the strange environment.104 This space is the scene in which the expedition members perform their masculinity undeterred by the ‘eternal winter’. The scene, showing officers and men engaged in almost every conceivable outdoor activity, is unparalleled in Browne’s surviving work, which often shows a landscape, occasionally foregrounded with two figures.

While the panorama booklet shows the exact layout of the visual elements in the exhibition itself, an engraving in the Illustrated London News (Figure 4.8), which appeared not long after the opening of the panorama, provides perhaps the most vivid representation of its winter portion.105 Despite the monochromatic constraints, the engraver has skilfully conveyed the luminosity and dramatic effects of the panorama. The large illustration covers almost half a page and takes immediate precedence over the text.

The image of ‘masculine’ work displayed in Burford’s panorama, so clearly shown by the Illustrated London News engraver (Figure 4.8) and in the panorama booklet, contrasts sharply with the domestic role of the ship as a home when wintering over, a home that included sewing and laundry duties, tasks more typically associated with women’s work. As Heather Davis-Fisch has noted, the space of the ship was a domesticated one.106 Although Ross’s log for the Enterprise during this period records activities such as building the observatory, trapping foxes, and building the snow wall, these are described over a period of several months, whereas in the panorama the activity is clustered together simultaneously, creating a busy scene. In the background, barely visible, men pull a sledge through the darkness, resulting in a picture that includes a total of thirty human figures. The panorama contrasts sharply with the image that first-hand accounts often provide, which includes ample time for reading, drawing, and the necessity of keeping house. For example, John Matthews, who wintered in the Arctic for six years aboard the Plover (1848–54) described in his journal how he washed blankets on the ice in a tub with soap and boiling water: ‘Indeed, Mother and Sister both, I may say that if you only saw me you would willingly hire me for your monthly wash.’107 William Chimmo, aboard the Herald (the Plover’s supply ship), recounts at length in his narrative the manner by which costumes, including those for an ‘elderly lady’, a ‘servant maid’, and a ‘bride’, for a theatre performance were created: ‘The midshipman’s berth was like a dressmaker’s shop! All were employed, even those who could but “sew on a button” … while those who had the advantage of sisters had learned to go through the more critical part of cutting out the dress.’108

Sherard Osborn described a typical day in winter on the subsequent Austin expedition of 1850 to 1851 in his published narrative: ‘knots of two or three would, if there was not a strong gale blowing, be seen taking exercise at a distance from the vessels; and others, strolling under the lee, discussed the past and prophesied as to the future … If it was a school night, the voluntary pupils went to their tasks, the masters to their posts; reading men producing their books, writing men their desks, artists painted by candle-light, and cards, chess, or draughts, combined with conversation, … served to bring round bed-time again.’109 The outdoor activity that Osborn described is leisurely, sociable, and done to break ‘monotony’, which was ‘the only disagreeable part of our wintering’.110 His references include the exercise that could be taken when the weather was fine and the opportunities to learn, paint, read and write, or play games during the winter period. His words are a far remove from the frenzy of activity depicted in the panorama’s winter portion, as rendered in the engraving of the panorama by the Illustrated London News.

The summer half of the panorama also displayed a more overtly masculine Arctic than that of Browne. While the birds in flight in Browne’s original watercolour (Figure 4.3) signify life, they also give a tranquillity to the scene; in the panorama, this contemplative image has been replaced with the presence of a bear being hunted, drawing attention to an activity that is both masculine and novel.

Neither does the lithograph Great Glacier, Near Uppernavik (Figure 4.4), intended for a more elite and scientific audience, show the active men who populate the panorama, but two restful and contemplative figures – the artist and his companion – who are calm and tranquil, relaxed in their environment, embodying a sense of place through their recording of the surrounding environment. In the lithograph, a rock outcrop is included in the foreground, providing a platform where the individuals are at ease. These figures, who here observe the glacier, can be seen in one of Browne’s three surviving watercolours from the same expedition, Coast of N. Somerset (1849), in the Canadian archipelago.111 Although a different location is delineated in this Arctic sketch, the two relaxed figures, one seated and one standing, appear. These figures too are less overtly active than their counterparts in the panorama, for they are scientific observers who have no need to do battle with the Arctic. Their purpose is to observe and record, while in the picture itself they provide a sense of scale.

The overt display of masculine activity in the panorama suggests characteristics of a moral sublime such as ‘intrepid fortitude’ and a disregard for ‘every feeling arising from the consideration of himself’112 as they endeavoured to find Franklin in a ‘trackless waste of everlasting ice and snow’.113 The booklet accompanying the panorama described how the search expedition had to ‘grapple with difficulties of no ordinary nature’ and ‘endure toil and privation, and the perilous incidents … which, by skill, daring, and steady perseverance, they triumphantly surmounted. The whole enterprise was nobly and gallantly conducted.’114 This text complements the visual depiction of the Ross expedition through the panorama, which sends a clear message of masculinity that was far removed from the visual records created by the expedition members like Browne. As Catherine Lanone has pointed out, ‘the discourse of polar exploration was a gendered discourse, casting men as heroic discoverers and women as compliant admirers endlessly waiting for their return – and their stories’.115

In fact, it was not uncommon for women to accompany their husbands on long whaling voyages, which included those that ventured into Arctic waters. It is also recorded that a single ‘Englishwoman’ took part in the search for Franklin aboard a private yacht, the Nancy Dawson, in 1849. Referred to as the ‘heroine of Point Barrow’ in a narrative by an anonymous midshipman not published until 1860, her exploits do not seem to have been known to the general public in the early 1850s.116 Her presence at theatre performances and parties was remarked upon on the Herald and the Plover where ‘her society was much sought after’, and she joined in the singing with a rendition of ‘Love’s Young Dream’ and ‘Erin my Country’.117 Another member of the Plover’s crew noted privately: ‘I must here mention that he [Robert Sheddon, the captain of the Nancy Dawson] had an Englishwoman with him who will gain a little celebrity by her voyage being the only one who has ever been in those latitudes before her name I believe is Emily.’118

Sublime Effects: Staging the Aurora Borealis

Added to the desolate winter scene was a meteorological phenomenon that heightened the intensity of the public’s experience. Burford’s Summer and Winter Views included the depiction of the aurora borealis, or northern lights, which vividly illuminated the winter portion of the panorama. Its appearance here emphasises the use of the Arctic and of the canvas as a dramatic space in which novel meteorological events are staged. The presence of the mysterious aurora was a significant way in which the places the expeditions lived in were transformed into supernatural and sublime spaces, in order to attract attention, draw visitors, and maximise profits amidst the multitude of attractions available at Leicester Square. Even a short announcement for the panorama’s opening in the Illustrated London News found space to remark upon the ‘sublime effects of an Aurora Borealis’ that appeared in Summer and Winter Views.119

The aforementioned Mr Booley also noted the ‘vivid Aurora Borealis … by night or day’,120 while for William Thackeray’s fictional, satirical letter-writer Goliah Muff in Punch, the ‘livid northern lights, the killing glitter of the stars; the wretched mariners groping around in the snow’ were so alarming that he ‘would not allow [his] children to witness it’.121 The Literary Gazette felt that the presence of sunshine and the aurora in the summer and winter portions respectively served ‘only as if to mock the sterility and utter coldness of the world’.122 For the writer in the Observer, the winter view was ‘appalling’. ‘A scene of more perfect desolation than that which is here presented to the eye could not be imagined.’123 In the Era, the reviewer noted that ‘the phenomenon of the Aurora Borealis is very cleverly treated by the artist; it is represented as it appears towards the magnetic pole, in brilliant coruscations of every prismatic colour … we much question if these mimic regions will not be visited by all who take any interest in the fate of Sir John Franklin.’124

A key way, however, in which the panorama, both visually and in its descriptive text, differed from what we know of Browne’s visual experience of winter in Port Leopold was in the depiction of the aurora borealis. Taking the engraving that appeared in the Illustrated London News of November 1849 (Figure 4.6) and the lithograph Noon in Mid-Winter (Figure 4.7) as the closest thing we have to Browne’s primary visual record of winter quarters, we observe that the headlands in both renderings are in roughly the same places and the subject matter is ostensibly the same. The most obvious difference is the complete absence of the aurora borealis in the earlier engraving and in the lithograph. The engraving is devoid of any activity, either meteorological or human. Not a single figure is to be seen, and yet it is a calm and contemplative image showing the relative safety of ships wintering over in darkness. The lithograph Noon in Mid-Winter differs again. Here a single stationary figure observes the glow of the midwinter sun visible on the horizon, while two less-distinct human forms appear closer to the ship. The title, Noon in Mid-Winter, emphasises the strangeness of the winter darkness, but the absence of the aurora in both is notable in comparison to the panorama.

By contrast, Burford’s booklet explains: ‘Towards the south the hemisphere is splendidly illuminated by that extraordinary and beautiful phenomenon, the Aurora Borealis, – vividly darting its brilliant corruscations towards the zenith, and tinging the snow with its pale mellow light.’125 The language suggests features of the Burkean sublime such as suddenness, dramatic transitions between dark and light, and extreme height. Later, in more detail, Burford repeated the phrase ‘brilliant corruscations of every prismatic colour’. The reader is informed that the phenomenon is ‘during the winter months almost constantly seen’.126

The Illustrated London News, which included an engraving of part of the winter half of the panorama (Figure 4.8), also drew attention to the aurora in its picture: ‘The right-hand horizon glows with the splendour of an Aurora Borealis.’127 The rays of light that represent the phenomenon here in the Illustrated London News are far more brilliant, dramatic, and obvious than in the booklet, reminding us that the booklet was intended to act as a guide during a viewing of the panorama, and not as a replica of the panorama in miniature.

The reviewer in the Illustrated London News lauded the overall effect of the panorama, concluding: ‘The picture is painted throughout with wonderful power and intensity of effect, characteristic of the supernatural aspects of the Polar Regions.’128 This reference to the supernatural complements the sublime and indicates the powerful attraction of mystery in the nineteenth century, something that still shrouded the polar regions. The uncertain scientific understanding of the aurora at the time meant that the phenomenon was still an object of some mystery,129 although it had been established in the early part of the nineteenth century that it occurred only in certain latitudinal zones.130 Many questions regarding the nature of the aurora, its origins, and appearance were still being debated around the time of the Franklin searches, and magnetic properties were an important facet of its study.131 A connection between the aurora and magnetism had been identified in the early nineteenth century.132 Geomagnetism (then known as terrestrial magnetism) was an important science, and the search expeditions from Britain were provided with equipment to take readings in the vicinity of the magnetic north pole.133 The interaction of solar winds with the earth’s magnetic field produce the aurora, thus making geomagnetism and the occurrence of the aurora inextricably linked. It was standard practice to record auroral activity among expeditions sent to the Arctic during the nineteenth century, and The Admiralty Manual of Scientific Enquiry recommended that auroral phenomena ‘should be minutely registered, and all their phases, especially the formation, extent, situation, movement, and disappearance of arches, or any definite patches or banks of light’.134

Although the aurora formed a central component and an attractive part of Burford’s composition, it fails to appear in any of Browne’s surviving visual records from the Arctic. Similarly, I have not come across depictions of it in the primary visual records from the Franklin search expeditions, unlike the phenomenon of the paraselene, of which several sketches exist. One could argue that the aurora was difficult to paint (which it undoubtedly was) and that it would have to be done from memory due to intense cold and winter darkness. However, the reason for its distinct absence in the visual records becomes clearer when reading the ship’s log of the Enterprise that winter.135 The log recorded daily events or routines and meteorological information including auroral activity and shows that, far from the phenomenon being a regular occurrence, many days went by without it being sighted. When it does appear in the logbook it is often described as a ‘faint aurora seen in the S to SE’.136 Only on one occasion is it recorded as being ‘brilliant’,137 using an adjective that comes nearest to the language employed in the public media. James Douglas Gilpin, clerk on the Investigator, wrote a serialised version of the expedition events for Nautical Magazine and described the aurora thus: ‘The Aurora Borealis had shown itself frequently, but never in such splendour as I had expected to see it … In colour it was a light yellowish tinge … a pinkish hue.’138 The clerk’s expectations underline the association of the aurora more generally with high northern latitudes in the popular imagination. Although he suggests that the aurora was frequent, the logbook does not corroborate his statement. Significantly, Gilpin did not experience it in the ‘splendour’ he had expected, implying that widespread descriptions of the aurora as a specifically Arctic phenomenon in the nineteenth century leaned sharply towards hyperbole.

While Ross does not comment on the aurora in his official Admiralty report,139 other commentators, on successive search expeditions in the same area, expressed some dismay at the lack of brilliancy and frequency of the aurora. Osborn, who travelled to the Arctic for the first time on the Austin expedition in 1850, remarked: ‘With one portion of the phenomena of the North Sea, we were particularly disappointed – and this was the aurora. The colours, in all cases, were vastly inferior to those seen by us in far southern latitudes, a pale golden or straw colour being the prevailing hue; the most striking part of it was its apparent proximity to the earth.’140 Belcher, commanding a five-ship search expedition in 1852–4, had a similar complaint:

November 30. – About this period the season becomes extremely monotonous, and one is reduced to all kinds of imaginary reasons to account for the absence of expected phenomena, more especially the aurora … I could hardly understand its prolonged absence. I had observed it, to the north of Behring’s Strait, on the 25th August and continuously up to the 5th October, in its greatest brilliancy; and in Wales, at Swansea, in August.141

To Belcher’s officers, John Cheyne and Walter May, the aurora became an elusive female whom they tried to capture with the magnetometer and electrometers.142 Walter May also mentioned the delay in the aurora’s appearance in his journal of the voyage, meaning that several months had passed during which it should have been possible to view the phenomenon. May’s entry for 10 December 1852 noted: ‘A good Aurora seen last night to the East. It is the first good one we have yet had in this country.’143 The following night, the expedition again witnessed the aurora: ‘We were favoured last night by a beautiful Aurora, It was first seen about 2.50 AM on the Southern horizon and gradually [neared?] the ship and eventually formed a complete arch over to the top of the hill on which the wires are placed, it was attracted by the wires, no doubt, for at one time it could not have been more than 100 feet from us – The magnetometer in the Observatory was affected but not the Electrometer.’144 There is no mention here, then, of its sublime effects, although the aurora can be ‘beautiful’ and there is clearly an expectation of the display to be visually arresting. It was not only the searchers for Franklin who recorded disappointment, as earlier records from expeditions in the area of the Northwest Passage attest.145 Ultimately, the written record shows that, far from being consistently seen in all parts of the Arctic, the aurora could be a more elusive event.

The explanation for the aurora’s infrequent and unimpressive displays becomes clear when the locations of winter quarters of the expeditions in question are considered. The search expeditions that entered the archipelago via Baffin Bay were so far north that they were within the auroral oval that forms around the geomagnetic north pole, which also explains why it was seen in the southern skies. And yet somehow, by the time of the panorama Summer and Winter Views, the aurora had become so synonymous with the polar regions that it was unthinkable not to include it when a large public exhibition was created. The aurora borealis had become a ‘crucial component’ in the construction of the Arctic imaginary.146

Conclusion

The panorama was such a convincing illusion that people regarded it as a realistic source of information with the ability to bring them closer to the very place where the Franklin expedition might be. The reviewer in the Era considered that, given the concern for the missing expedition, ‘anything tending to enlarge the sphere of thought, or add to the scanty stock of information relative to the trackless waste of everlasting ice and snow, is sought for with the utmost avidity’.147 Lady Franklin herself found the spectacle so compelling that she ‘remained two hours inspecting the picture, which must possess a peculiar interest to her, as being near the place in which her husband and his expedition are supposed to be, if still alive’.148

The overall effect of Burford’s panorama was to displace the viewer in time and space, transporting them not to the Arctic but to a supernatural space in which the expedition’s sense of place was lost in the overwhelming aspect of a sublime expanse of icy pinnacles, light and dark, tumultuous upheaval, and masculine endeavour, combining a sublime that was at once gothic, mysterious, and supernatural. By closely examining the panorama based on William Browne’s work, I have shown how the visual record of an expedition could be transformed for popular consumption and that the panorama Summer and Winter Views, alleged to imitate reality, differed vastly from the Arctic visual experience of William Browne. The gothicisation of the icescape through the panorama had the effect of positing the search ships as well-matched foes of Arctic ice.

The public representation of the Arctic in the 1850s, as actions, icescapes, and phenomena were enhanced, provided a theatrical stage on which to demonstrate the gallant efforts of the search parties. While Browne’s figures in sketches and lithographs often epitomise calm, rational scientific observation, those in the panorama engage in more active, overtly masculine endeavour. The very public panorama emphasised the moral sublime in action and the fervour of activity that was being undertaken in the search for Franklin. It showed movement and mobility through space rather than stillness in place. The result was that the Arctic became less of a place in the geographic sense and more a space in which the moral sublime could be effectively displayed. The experience of viewing the panorama, visited by a broad cross-section of society, must have left an overwhelming impression on the minds of those who saw it. It is possible that even naval officers were misled by its vivid depiction of the aurora, as records of disappointment concerning the aurora are found in Arctic narratives. The wide appeal of the panorama, and the affordable cost of admission, meant that this theatrical spectacle, showcasing British bravery amidst ‘savage horrors’, had the power to ‘attract the public as the needle to the pole’.149