Vitamin A toxicity is an uncommon but recognized cause of intracranial hypertension; Reference Vidailhet, Rieu and Feillet1,Reference Ramkumar, Verma and Crow2 however, the link between pediatric acute hypervitaminosis A and intracranial hypertension is mostly inferred from bulging fontanel identified on public health campaigns in developing countries using megadoses of synthetic vitamin A to combat systemic vitamin A deficiency, xerophthalmia, and infant mortality, Reference Haider, Sharma, Bhutta and Bhutta3,Reference Imdad, Ahmed, Bhutta and Bhutta4 or from treatment of severe measles. Reference Stinchfield and Orenstein5 There are only rare case reports showing a direct correlation with confirmed elevated opening pressure. Reference Stinchfield and Orenstein5 We present an infant girl who developed acute intracranial hypertension following an extreme overdose of vitamin A.

A 17-month-old non-immunized girl presented to the emergency department for emesis and four days of fever. Other than a prenatal diagnosis of a single kidney, she was previously healthy with normal development.

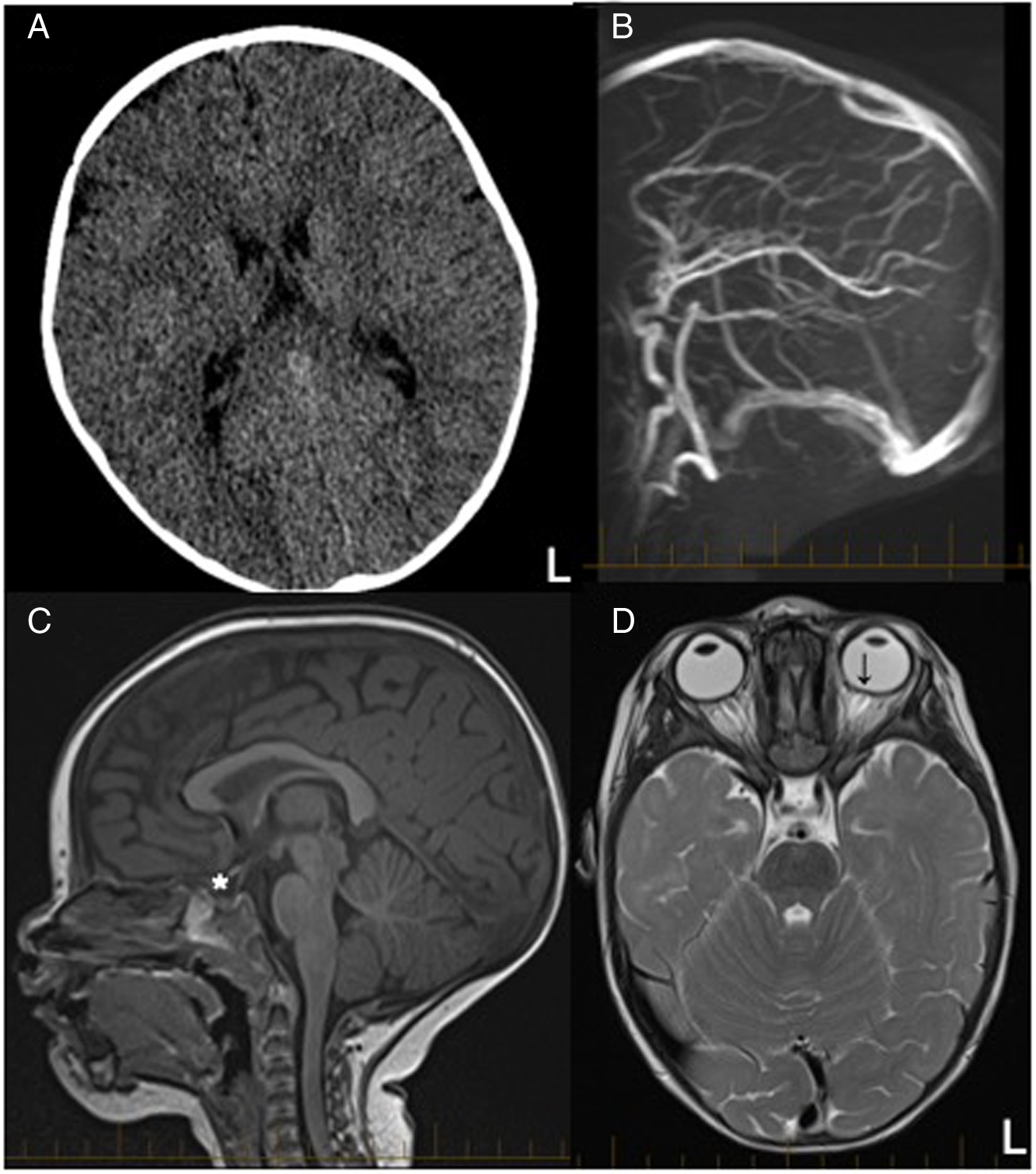

She was irritable with a bulging fontanel, but her neurological and systemic examinations were otherwise unremarkable, though fundi were not visualized. An urgent computed tomography head without contrast was normal (Figure 1A). She underwent a complete septic workup. Under conscious sedation, the lumbar puncture opening pressure was elevated at 34.5 cm H2O (normal range 5–28 cm H2O). Reference Ramkumar, Verma and Crow2 The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis was reassuring (white blood cells 0, red blood cells 2, protein 0.19 g/L, glucose 3.4 mmol/L). The remainder of her workup revealed only leukopenia (white blood cells 2.9 × 109/L) and increased C-reactive protein (20.8 mg/L). As a precaution, she was started on antibiotics at meningeal dosing.

Figure 1: Neuroimaging evaluation of an infant with intracranial hypertension suspected to be secondary to vitamin A toxicity. Legends: Neuroimaging of acute vitamin A toxicity presenting with intracranial hypertension. (A) Axial CT scan without contrast reported as normal with normal ventricle size. (B) The magnetic resonance venogram confirmed patent intracranial veins and the absence of cerebral sinus venous thrombosis. A developmental variant of a septated descending segment of the superior sagittal sinus was also identified (not shown). T1 sagittal (C) and T2 axial (D) MRI sequences show signs of intracranial hypertension with a partially empty sella (*) and abnormal flattening of the sclera with mild bulging of the head of the optic nerves of the left eye (↓). L = Left.

Parallel to investigations, the history was clarified. After one day of fever and low energy, her parents elected to follow recommendations circulated on social media by a naturopathic healthcare provider. The patient received 400,000 international units (IU) of vitamin A and 50,000 IU of vitamin D daily for two days per os. This total vitamin A dose corresponds to 600 times the recommended dietary allowance (RDA) for the patient’s age. Reference Vidailhet, Rieu and Feillet1

Low-dose acetazolamide (16 mg/kg/day) was started for symptomatic management of intracranial hypertension. She had regular capillary blood gas and extended electrolytes monitoring for possible side effects of acetazolamide and risks of hypercalcemia with hypervitaminosis A and D. She never had signs of acute vitamin D toxicity.

The next morning, she showed clinical improvement. Her magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with magnetic resonance venogram revealed no evidence of cerebral sinus venous thrombosis (Figure 1B), but showed signs of intracranial hypertension with mild optic head protrusion in her left eye with a partially empty sella (Figure 1C and D). The ophthalmology assessment did not identify objective signs of visual field deficits, but confirmed “mild” bilateral papilledema without a specified grade.

Antibiotics were discontinued following negative CSF, blood, and urine cultures, and her workup identified no other possible causes of intracranial hypertension. She was diagnosed with intracranial hypertension secondary to acute vitamin A toxicity. She developed metabolic acidosis after two days of acetazolamide treatment. Since her irritability and bulging fontanel had resolved, acetazolamide was stopped without recurrence of symptoms during the hospitalization, supporting the principal role of discontinuing the offending agent when managing intracranial hypertension. At five-month follow-up, the patient was thriving with no neurological or vision concerns on history or examination.

Vitamin A is a lipid-soluble vitamin found in pharmaceutical supplements and common foods. Reference Haider, Sharma, Bhutta and Bhutta3,Reference Penniston and Tanumihardjo6 This micronutrient has many roles, including immunity, vision, hematopoiesis, epithelial tissue, and embryogenesis. Reference Vidailhet, Rieu and Feillet1,Reference Haider, Sharma, Bhutta and Bhutta3 The RDA of vitamin A varies with age. One- to three-year-old children should receive 400 μg retinol equivalents (RE)/day with a safe upper limit of 800 μg RE/day, Reference Vidailhet, Rieu and Feillet1 which corresponds to 1333 IU and 2667 IU of vitamin A, respectively. Acute hypervitaminosis A has been reported with acute ingestion of 20 to 100 times the RDA. Reference Penniston and Tanumihardjo6 Symptoms of acute toxicity include bulging fontanel, headaches, vomiting, diarrhea, anorexia, myalgia, vision disorders, and irritability, Reference Vidailhet, Rieu and Feillet1,Reference Haider, Sharma, Bhutta and Bhutta3,Reference Stinchfield and Orenstein5 while symptoms of chronic toxicity include liver damage, headaches, vomiting, desquamation, osteopenia, arthralgia, alopecia, and teratogenicity. Reference Vidailhet, Rieu and Feillet1–Reference Haider, Sharma, Bhutta and Bhutta3,Reference Penniston and Tanumihardjo6 Symptoms may be accompanied by hypercalcemia, transaminitis, anemia, and coagulopathy. Reference Vidailhet, Rieu and Feillet1,Reference Ramkumar, Verma and Crow2,Reference Penniston and Tanumihardjo6 Unfortunately, vitamin A serum level, measured via serum retinol level, is an unreliable marker, as proven by case reports of hypervitaminosis A with normal serum levels. Reference Penniston and Tanumihardjo6

Acute hypervitaminosis A usually occurs secondary to excessive supplementation. Reference Ramkumar, Verma and Crow2 The vitamin A doses used in public health campaigns and treatment of severe measles, 25,000 IU to 400,000 IU, are in the toxic range. Reference Haider, Sharma, Bhutta and Bhutta3,Reference Imdad, Ahmed, Bhutta and Bhutta4–Reference Penniston and Tanumihardjo6 A pooled analysis showed a 53% increased risk of bulging fontanel with high-dose vitamin A supplementation. Reference Haider, Sharma, Bhutta and Bhutta3 Another Cochrane review confirmed an increased risk of bulging fontanel in the 24 to 72 hours following vitamin A treatment. There was no significant increase in other side effects, including vomiting, irritability, fever, and convulsions. Reference Imdad, Ahmed, Bhutta and Bhutta4

A proposed mechanism for intracranial hypertension secondary to hypervitaminosis A is that vitamin A metabolites impair CSF reabsorption, possibly through gene regulation from all-trans-retinoic acid primarily found in the meninges and choroid plexus. Reference Libien, Kupersmith and Blaner7

Prompt evaluation and treatment are essential in intracranial hypertension to avoid irreversible optic nerve injuries and vision impairment. When a cause is identified, the management focuses on the underlying etiology. Concurrently, symptomatic management can help reduce CSF production, with the first-line therapy being acetazolamide, a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor. Reference Ramkumar, Verma and Crow2 Acute vitamin A toxicity management is supportive, with exposure cessation, hydration, and monitoring for signs of intracranial hypertension. Reference Ramkumar, Verma and Crow2 Moreover, acetazolamide may directly affect vitamin A metabolism. Reference Libien, Kupersmith and Blaner7

Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) is frequently used in the pediatric population. For example, a study reported that 43.9% of patients had taken a CAM product within the last 12 months and 6.0% on the day of the emergency visit. Reference Taylor, Dhir and Craig8 However, only 4.4% of the CAM products were reported to the emergency physician. Reference Taylor, Dhir and Craig8 The low disclosure rate raises concerns about possible adverse reactions and interactions.

In conclusion, with a confirmed elevated lumbar puncture opening pressure and signs of intracranial hypertension on brain MRI directly following a vitamin A overdose, this case illustrates that acute hypervitaminosis A could cause symptomatic intracranial hypertension in infants. However, based on this isolated case, we cannot comment if hypervitaminosis A is a common cause of intracranial hypertension in children. Our experience also demonstrates the importance of including a history of CAM in pediatric neurology consultations.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Endocrinology, Emergency medicine, General Paediatrics, and Ophthalmology teams who helped care for this patient.

Author Contributions

ML, MO, and KM conceptualized the case report, drafted the initial manuscript, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

No funding was secured for this case report.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.