Introduction: When Writing Means Correct Writing

1 See some recent examples below: The 11 extremely common grammar mistakes that make people cringe—and make you look less smart: Word experts, by Kathy and Ross Petras, March 2021: https://www.cnbc.com/2021/03/24/common-grammar-mistakes-that-make-people-cringe-and-make-you-look-less-smart-word-experts.html 22 grammar mistakes that make you look really stupid, by Steve Adcock, December 2020: https://www.theladders.com/career-advice/22-common-grammar-mistakes-that-make-you-look-really-stupid Why are students coming into college poorly prepared to write? https://www.cmu.edu/teaching/designteach/teach/instructionalstrategies/writing/poorlyprepared.html Our students can’t write very well—It’s no mystery why: https://www.edweek.org/teaching-learning/opinion-our-students-cant-write-very-well-its-no-mystery-why/2017/01

2 Thank you to my students in English linguistics courses in the fall of 2022 for sharing their ideas and consenting to my sharing them. The first three notes where offered by students who wished to share their work anonymously, while one note about family and friends was shared by Mary Hoskins.

3 For the full blog entry, see: www.essayhell.com/2015/06/how-to-write-a-college-application-essay-even-if-you-cant-write/

4 In these ways, the writing myths in this book can be thought of as contributors to the broader literacy myth characterized by Harvey Graff; like the broader literacy myth, correct writing myths are commonplace, articulated through institutions, and capable of imbuing correct writing with immeasurable, ineffable grandeur.

5 The pronouns it, I, and you, and negation words, commonly collocate, or hang out with, ain’t in the 1.9-billion word corpus of Global Web-based English (GloWbe) developed by M. Davies. See more here: www.english-corpora.org/glowbe/.

6 Because correct writing has been used to keep so many people outside the proverbial gates, some writing researchers argue we should write differently in higher education, avoiding academic writing and standardized English. This book takes a different tack. It assumes we need to explore the history and nature of correct writing, and it focuses as much on language itself – patterns across different kinds of writing – as it does on language beliefs. It assumes that exploring a continuum of writing (including correct writing) gives us the best chance of learning more and mythologizing less.

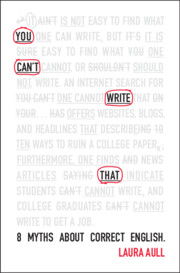

Myth 1 You Can’t Write That

1 As happened, for instance, with the spelling of Biowulf and Beowulf in the tenth century; see the British Library images and descriptions here: https://blogs.bl.uk/digitisedmanuscripts/2013/05/you-say-beowulf-i-say-biowulf.html.

2 Before efforts to make spelling more uniform were attempts to make handwriting, style, and form more uniform in thirteenth-century land deeds and other legal documents; see Flanders, J., A Place for Everything: The Curious History of Alphabetical Order. London, Picador: 2020. Likewise, earlier than the sixteenth century were smaller efforts toward standardization; see: C. Upward, and G. Davidson, The History of English Spelling, vol. 26. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2011.

3 Bishop Lowth wrote his popular Short Introduction to English Grammar in 1763 in the hope of supporting his son’s future Latin studies. Although Lowth does not seem to have intended this, his book is credited with bringing about the rise of prescriptive grammar and dialect-specific rules for rewarding certain writers and shaming others. See I.T.-B. van Ostade (2010), The Bishop’s Grammar: Robert Lowth and the Rise of Prescriptivism. Oxford, Oxford University Press. Some sources indicate that Murray plagiarized Lowth as a principal source for his own usage guide. See E. Vorlat (1959), The Sources of Lindley Murray’s “The English Grammar”, Leuvense Bijdragen, 48, 108–25.

4 A classic example is the great vowel shift, which moved vowel sounds from being produced (through air propulsion) higher to lower in the mouth, and from front to back in the mouth, through several shifts in the fourteenth to the seventeenth century (e.g., here are some examples transcribed into the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA): /knaIt/ → /naIt/; /gnæt/ → /næt/; /nemə/ → /nem/). Standardized spelling didn’t keep up with this shift, and vowels continue to change in this direction without changes in standardized spelling.

5 English has six vowel letters: a, e, i, o, u and sometimes y, but it has at least 15 vowel sounds in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA).

6 Resources that separate informal and formal writing, for instance, include: the BBC (www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/guides/z996hyc/revision/1); Cambridge Assessment (www.cambridgeenglish.org/learning-english/activities-for-learners/c1w001-formal-and-informal-writing), and resources from various universities: Massey University (https://owll.massey.ac.nz/academic-writing/writing-objectively.php), the University of Southern California (https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/academicwriting), University Technology Sydney (www.uts.edu.au/current-students/support/helps/self-help-resources/grammar/formal-and-informal-language), Lund University (https://awelu.srv.lu.se/grammar-and-words/register-and-style/formal-vs-informal/), the University of Melbourne (https://students.unimelb.edu.au/academic-skills/explore-our-resources/developing-an-academic-writing-style/key-features-of-academic-style).

7 Calls for formal English to be “direct” and “plain” appear over several centuries. Generally, these calls tend to evoke a single, moralized standard of correct writing – with less jargon and shorter sentences. Linguist Deborah Cameron charts the Plain English debates throughout the past 500 years, identifying times when “Latin eloquence” won over “plainness,” as well as times when “plainness” won: the Enlightenment period emphasized the need for plain English; in the mid-twentieth century Sir Ernest Gower published Plain Words for British civil servants; and the late twentieth century The Times style guide espoused plainness (D. Cameron, Verbal Hygiene. Abingdon, Oxfordshire: Routledge, 2012). In these debates, Cameron writes, “using a certain style of language becomes a moral matter” (p. 67; emphasis hers). Ultimately, discussions about plain English do not clearly agree on what makes something plain, why it matters, or who gets to decide; and as with much discussion of language, much more is at stake than which words to use. In the case of plain English, language is a “a mark of judiciousness, impartiality, and good sense,” and “a symbol of the struggle against totalitarianism” (Ibid.)

8 Angelou, M. (1969). I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings. New York: Bantam.

9 I derive these five purposes from synthesizing applied linguistics and writing research, especially corpus linguistic analysis of patterns in a range of English use, including the following:

Ädel, A. (2017). Remember that Your Reader Cannot Read Your Mind: Problem/solution-oriented Metadiscourse in Teacher Feedback on Student Writing, English for Specific Purposes, 45, 54–68.

Aull, B. (2019). A Study of Phatic Emoji Use in WhatsApp Communication, Internet Pragmatics, 2(2), 206–32.

Aull, L. L. (2020). How Students Write: A Linguistic Analysis. New York: Modern Language Association.

Aull, L. L., D. Bandarage, and M.R. Miller (2017). Generality in Student and Expert Epistemic Stance: A Corpus Analysis of First-year, Upper-level, and Published Academic Writing, Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 26, 29–41.

Aull, L. L. and Z. Lancaster (2014). Linguistic Markers of Stance in Early and Advanced Academic Writing: A Corpus-based Comparison, Written Communication, 31(2), 151–83.

Bai, Q., Q. Dan, Z. Mu, and M. Yang (2019). A Systematic Review of Emoji: Current Research and Future Perspectives, Frontiers in Psychology, 10: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02221.

Barton, E. L. (1995). Contrastive and Non-Contrastive Connectives Metadiscourse Functions in Argumentation, Written Communication, 12(2), 219–39.

Barton, E. L. and G. Stygall (2002). Discourse Studies in Composition. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

Biber, D. (1988). Variation across Speech and Writing. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. 1988.

Biber, D., et al. (2002). Speaking and Writing in the University: A Multidimensional Comparison, TESOL Quarterly, 36(1), 9–48.

Biber, D. and J. Egbert. (2018). Register Variation Online. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Biber, D. and B. Gray. (2016). Grammatical Complexity in Academic English: Linguistic Change in Writing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Black, K. E. (2022). Variation in Linguistic Stance: A Person-Centered Analysis of Student Writing. Written Communication, 39(4), 531–563.

Brown, D. W. and C. C. Palmer (2015). The Phrasal Verb in American English: Using Corpora to Track Down Historical Trends in Particle Distribution, Register Variation, and Noun Collocations, in Studies in the History of the English Language VI: Evidence and Method in Histories of English, eds. M. Adams, L. J. Brinton and R. D. Fulk, 71–97. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Charles, M. (2006). The Construction of Stance in Reporting Clauses: A Cross-disciplinary Study of Theses, Applied Linguistics, 27(3), 492–518.

Crismore, A. (1983). Metadiscourse: What it Is and how it Is Used in School and Non-school Social Science Texts, in Center for the Study of Reading. Urbana-Champaign: University of Illinois Press.

Crismore, A. and R. Farnsworth (1990). Metadiscourse in Popular and Professional Science Discourse, in The Writing Scholar: Studies in the Language and Conventions of Academic Discourse, eds. A. Crismore and R., 45–68. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Crismore, A., R. Markkanen, and M.S. Steffensen. (1993). Metadiscourse in Persuasive Writing: A Study of Texts Written by American and Finnish University Students, Written Communication, 10(1), 39–71.

Crossley, S. A. (2020). Linguistic Features in Writing Quality and Development: An Overview, Journal of Writing Research, 11(3), 415–43.

Dixon, T., Egbert, J., Larsson, T., Kaatari, H., & Hanks, E. (2023). Toward an empirical understanding of formality: Triangulating corpus data with teacher perceptions. English for Specific Purposes, 71, 161–177.

Gawne, L. and G. McCulloch (2019). Emoji as Digital Gestures, Language@ Internet, 17(2).

Goźdź-Roszkowski, S. (2011). Patterns of Linguistic Variation in American Legal English: A Corpus-based Study. Bern, Switzerland: Peter Lang.

Gray, B. (2010). On the Use of Demonstrative Pronouns and Determiners as Cohesive Devices: A Focus on Sentence-initial This/these in Academic Prose, Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 9(3),167–83.

Gray, B. and D. Biber. (2012). Current Conceptions of Stance, in Stance and Voice in Written Academic Genres, eds. K. Hyland and C. S. Guinda, 15–33. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Haas, C., Takayoshi, P., Carr, B., Hudson, K., & Pollock, R. (2011). Young people’s everyday literacies: The language features of instant messaging. Research in the Teaching of English, 45(4): pp. 378–404.

Hardy, J. A. and E. Frigina (2016). Genre Variation in Student Writing: A Multi-dimensional Analysis, Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 22, 119–31.

Hardy, J. A. and U. Römer. (2013). Revealing Disciplinary Variation in Student Writing: A Multi-dimensional Analysis of the Michigan Corpus of Upper-level Student Papers (MICUSP), Corpora, 8(2), 183–207.

Harwood, N. (2009). An interview-based study of the functions of citations in academic writing across two disciplines. Journal of pragmatics, 41(3), 497–518.

Ho, V. (2018). Using Metadiscourse in Making Persuasive Attempts through Workplace Request Emails, Journal of Pragmatics, 134, 70–81.

Holmes, J. (1984). Modifying Illocutionary Force, Journal of Pragmatics, 8(3), 345–65.

Hyland, K. (1998). Persuasion and Context: The Pragmatics of Academic Metadiscourse, Journal of Pragmatics, 30(4), 437–55.

Hyland, K. (2004). Disciplinary Discourses: Social Interactions in Academic Writing. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Hyland, K. (2005). Stance and Engagement: A Model of Interaction in Academic Discourse, Discourse Studies, 7(2), 173–92.

Hyland, K. (2005). Metadiscourse: Exploring Interaction in Writing. London: Continuum.

Hyland, K. and P. Tse (2004). Metadiscourse in Academic Writing: A Reappraisal, Applied Linguistics, 25(2): 156–77.

Kriaučiūnienė, R., La Roux, J., & Lauciūtė, M. (2018). Stance Taking in Social Media: the Analysis of the Comments About Us Presidential Candidates on Facebook and Twitter. Verbum, 9, 21–30.

Kuhi, D. and B. Behnam (2011). Generic Variations and Metadiscourse Use in the Writing of Applied Linguists: A Comparative Study and Preliminary Framework, Written Communication, 28(1), 97–141.

Lakoff, G. (1973). Hedges: A Study in Meaning Criteria and the Logic of Fuzzy Concepts, Journal of Philosophical Logic, 2(4), 458–508.

Lee, C., & Barton, D. (2013). Language online: Investigating digital texts and practices. Abingdon, Oxfordshire: Routledge.

Lee, J. J. and N. C. Subtirelu (2015). Metadiscourse in the Classroom: A Comparative Analysis of EAP Lessons and University Lectures, English for Specific Purposes, 37, 52–62.

Li, T. and S. Wharton (2012). Metadiscourse Repertoire of L1 Mandarin Undergraduates Writing in English: A Cross-contextual, Cross-disciplinary Study, Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 11(4), 345–56.

McNamara, D. S., S. A Crossley, and P. M. McCarthy, (2010). Linguistic Features of Writing Quality, Written Communication, 27(1): 57–86.

Mao, L.R. (1993). I Conclude Not: Toward a Pragmatic Account of Metadiscourse, Rhetoric Review, 11(2): 265–89.

Mauranen, A. (2018). Second Language Acquisition, World Englishes, and English as a Lingua Franca (ELF), World Englishes, 37(1): 106–19.

McCulloch, G. (2020). Because Internet: Understanding the New Rules of Language. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Mur-Duenas, P. (2011). An Intercultural Analysis of Metadiscourse Features in Research Articles Written in English and in Spanish, Journal of Pragmatics, 43(12), 3068-79.

Myers, G. (2013). Stance-taking and public discussion in blogs. In Self-Mediation (pp. 55–67). Routledge.

Myhill, D. (2008). Towards a Linguistic Model of Sentence Development in Writing, Language and Education, 22(5), 271–88.

Nesi, H. and S. Gardner (2012). Genres across the Disciplines: Student Writing in Higher Education. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Römer, U. (2009). The Inseparability of Lexis and Grammar: Corpus Linguistic Perspectives, Annual Review of Cognitive Linguistics, 7(1), 140–62.

Rossen-Knill, D. (2011). Flow and the Principle of Relevance: Bringing our Dynamic Speaking Knowledge to Writing, Journal of Teaching Writing, 26(1), 39–67.

Silver, M. (2003). The Stance of Stance: A Critical Look at Ways Stance Is Expressed and Modeled in Academic Discourse, Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 2(4), 359–74.

Simpson, P. (1990). Modality in Literary-critical Discourse, in The Writing Scholar: Studies in Academic Discourse, ed. W. Nash. Newbury Park, CA: SAGE.

Squires, L. (2010). Enregistering Internet Language, Language in Society, 39(4), 457–92.

Swales, J. (1990). Genre Analysis: English in Academic and Research Settings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Swales, J. (2004). Research Genres: Explorations and Applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tannen, D., and A. M. Trester (eds.). (2013). Discourse 2.0: Language and New Media. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

Thompson, S. E. (2003). Text-structuring Metadiscourse, Intonation and the Signalling of Organisation in Academic Lectures, Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 2(1), 5–20.

Triki, N. (2019). Revisiting the Metadiscursive Aspect of Definitions in Academic Writing, Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 37, 104–16.

Vande Kopple, W. (1985). Some Exploratory Discourse on Metadiscourse, College Composition and Communication, 36(1), 82–93.

Vande Kopple, W. J. (2012). The Importance of Studying Metadiscourse, Applied Research on English Language, 1(2): 37–44.

Widdowson, H. (2015). ELF and the Pragmatics of Language Variation, Journal of English as a Lingua Franca 4(2), 359–72.

Myth 2 You Can’t Write That in School

1 The Dissenters were so called because they refused to take oaths to Anglicanism required of all English university students and teachers by the Act of Uniformity in 1662.

2 See a similar example in H. Blair, Lectures on Rhetoric and Belles Lettres. 1784: Robert Aitken, at Pope’s Head in Market Street.

3 This discussion focuses on language policies specifically, but many language policies also bear direct relationship to immigration debates and policies: For instance, more assimilationist immigration stances tend to mean more assimilationist language policies, whereas pluralist immigration stances and language policies more easily coexist; see: Fitzsimmons-Doolan, S. (2009), Is Public Discourse about Language Policy Really Public Discourse about Immigration? A Corpus-based Study, Language Policy, 8(4), 377–402. For a fuller discussion about language policy and immigration policy, see e.g., policies ibid., Eggington, W. and H. Wren (1997), Language Policy: Dominant English, Pluralist Challenges (Amsterdam; Philadelphia, PA: J. Benjamins), Ozolins, U. and M. Clyne (2001), Immigration and Language Policy, in The Other Languages of Europe: Demographic, Sociolinguistic, and Educational Perspectives, eds. G. Extra and D. Gorter (Clevedon: Multilingual Matters), 371–90; The Other Languages of Europe: Demographic, Sociolinguistic, and Educational Perspectives, 2001. 118: p. 371; Conrick, M. and P. Donovan (2010), Immigration and Language Policy and Planning in Quebec and Canada: Language Learning and Integration, Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 31(4), 331–45; G. Valdés (1997), Bilinguals and Bilingualism: Language Policy in an Anti-immigrant Age, International Journal of Society and Language, 127, 25–52.

4 Challenges include quality of instruction and student take-up of language study when it is no longer required. See a full UK Parliament 2021 report on languages in UK schooling here: https://lordslibrary.parliament.uk/foreign-languages-primary-and-secondary-schools/.

5 From the Las Vegas Sun, excerpt from letter prohibiting languages other than English on the school bus from the Superintendent of the Esmeralda County School District, reported in “Students told to hold (native) tongue” by Timothy Pratt in December 2007: https://lasvegassun.com/news/2007/dec/19/students-told-to-hold-native-tongue/?_ga=2.9182262.2083529048.1643643237-220150693.1643643237.

Myth 3 You Can’t Write That and Be Smart

1 In this search conducted in January, 2022, some quizzes note their bias toward native English speakers. Some note different quizzes for types of intelligence, such as verbal or emotional intelligence. Example links appear below:

Test Your Cognitive Skills!: www.test-iq.org/?gclid=Cj0KCQjw0KHBhDDARIsAFJ6UGizC0Rdq8WqouCuvEVZwjbOVFYCPQmpqu0DUUy3CktsvUMMLf_lcgoaArm7EALw_wcB.

Find Out Where You Stand with our Verbal IQ test: www.psychologytoday.com/us/tests/iq/verbal-linguistic-intelligence-test.

Have You Ever Wondered How Intelligent You Are Compared to Your Friends, Your Colleagues … and the Rest of the Nation?: www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/articles/2xhbqsm0NyPLfRzYqNl966M/how-intelligent-are-you.

When You Complete a Free IQ Test You Will Get an Estimate of Your IQ Score or the Number of Questions You Answered Correctly: www.123test.com/iq-test/.

An IQ Test Is an Assessment that Measures a Range of Cognitive Abilities and Provides a Score that Is Intended to Serve as a Measure of an Individual’s Intellectual Abilities and Potential: www.verywellmind.com/how-are-scores-on-iq-tests-calculated-2795584.

Online Assessment – USA Average IQ Score is 103.2: www.iqtestacademy.org/.

1782 Additional links, about IQ test challenges, history, and writing and “sounding intelligent”:

IQ Tests Are Known to Be Sensitive to Things like Motivation and Coaching: www.discovermagazine.com/mind/do-iq-tests-actually-measure-intelligence.

IQ Tests Have a Dark, Controversial History – But They’re Finally Being Used for Good: www.businessinsider.com/iq-tests-dark-history-finally-being-used-for-good-2017-10.

Want to Sound Intelligent? Write Plainly and Simply: https://medium.com/swlh/want-to-sound-intelligent-write-plainly-and-simply-6d7acc5ddd71.

Science Explains Why People who Love Writing Are Smarter: https://iheartintelligence.com/love-writing-smarter/.

3 At this time, standardized testing was already used in China in order to rank and select, and written rather than oral tests were used in Prussia. Mann had visited Prussia and concluded that US students were not so well prepared, fueling his idea that they should begin taking written examinations.

4 Burt recommended his findings to audiences including teachers and law enforcement agents, even though some of his ideas were fanciful and speculative. Take, for instance, Burt’s notion that “the near-sighted, or myopic perhaps because the things outside them look so blurred and indistinct, are peculiarly apt to be flung back upon their inner life; they brood and daydream,” which brings to mind Oscar Wilde’s Gwendolen in The Importance of Being Earnest, who says, “mamma, whose views on education are remarkably strict, has brought me up to be extremely short-sighted; it is part of her system; so do you mind my looking at you through my glasses?”

5 This four-domain model is based on research in progress with Norbert Elliot, and on Mislevy, R. (2018), Sociocognitive Foundations of Educational Measurement. (Abingdon, Oxfordshire: Routledge).

6 See a fuller history in Helen Patrick’s “Examinations in English after 1945” (www.cambridgeassessment.org.uk/news/examinations-in-england-after-1945-history-repeats-itself/) and in Examining the World (www.cambridgeassessment.org.uk/news/playlist/view/extracts-from-examining-the-world-playlist/) for Cambridge Assessment.

Myth 4 You Can’t Write That on the Test

1 In the UK in 1820, if you were aged fifteen or older, you and your peers would have less than two years of education between you (van Leeuwen, B. and J. van Leeuwen-Li (2015), Average Years of Education. IISH Datavers). In the US in 1850, if you were a white student anywhere between five and nineteen years old, you had about a 50–50 chance of being in school – and if you were not white, your chances were almost 0 (Snyder, T. (1993), 120 Years of American Education: A Statistical Portrait. US Department of Education, Office of Educational Research and Improvement).

2 The shift from speaking to writing also happened outside of English-medium higher education; for instance, the Baccalaureate examination used for university admission established by Napoleon in 1808 shifted from an oral to a written examination in 1830.

3 For more information on Morrill Act land seizures, treaties, and uses, see Robert Lee and Tristan Ahtone’s Land-Grab Universities Project: www.hcn.org/issues/52.4/indigenous-affairs-education-land-grab-universities.

4 Reported in Cambridge University News and Research, based on Andrew Watts’ research: www.cambridgeassessment.org.uk/news/how-have-school-exams-changed-over-the-past-150-years/

5 In “Turn your papers over,” Andrew Watts documents Amy’s letter as evidence of the similar “highs and lows” for past and present test takers.https://www.cambridgeassessment.org.uk/news/how-have-school-exams-changed-over-the-past-150-years/

6 See more examples from Cambridge assessment archives research here: www.cam.ac.uk/research/features/playing-croquet-with-the-examiner-he-was-much-like-other-people.

7 The answers are: adjective, and Beethoven, Wagner, Verdi.

8 Correct writing was rewarded in other ways, as well. In an example that illustrates the four myths so far, Oxford University awarded scholarships in 1870 for the best English essay on the topic “The reciprocal influence on each other of National Character and National Language.” Oxford University Gazette (1870) v.1-2 (1870–1872).

9 See Accuplacer’s exam candidate materials here: https://study.com/academy/popular/accuplacer-writing-tips.html.

10 For an in-depth discussion of Microsoft Grammar Checker, see Anne Curzan’s Fixing English.

11 For instance, the University of Aberdeen in Scotland offered an 1880 class in “English Language and Literature” said to cover “the higher Elements of English Grammar; the Principles of Rhetoric, applied to English Composition, and some portion of the history of English Literature.” Bain, A. (1866), English Composition and Rhetoric: A Manual (rev. American ed.). New York: D. Appleton and Co.

12 For all of the proposals from the UK Department of Education and Ofqual, see: www.gov.uk/government/consultations/proposed-changes-to-the-assessment-of-gcses-as-and-a-levels-in-2022/proposed-changes-to-the-assessment-of-gcses-as-and-a-levels-in-2022.

18013 See the following for more information on each examination task, where available:

Cambridge Junior Examination 1858 task: www.cam.ac.uk/research/features/playing-croquet-with-the-examiner-he-was-much-like-other-people.

Cambridge Examination for Women 1870 task: “You are requested to write an essay on one of the following subjects”: (https://books.google.jo/books?id=oLYIAAAAQAAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=university+oxford+women%27s+examination+paper&hl=en&sa=X&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=English%20examination&f=false).

STAT 2009 task: There are two parts to this test, and four comments are offered for each part. You are required to produce two pieces of writing − one in response to a comment from Part A, and one in response to a comment from Part B. Part A is a more formal public affairs issue that invites argument. Part B is a less formal topic that invites more personal reflection. One hour is allocated for this test, with an additional five minutes reading time. (For these and other examples, see https://stat.acer.org/files/STAT_CIB.pdf.)

Cambridge 2016 A-levels task: Julia Gillard makes an entry in her diary the night before she gives this speech. Write this entry (between 120 and 150 words), basing your answer closely on the material of the speech. The full writing exam can be found here: https://paper.sc/doc/5b4c363c6479033e61e6b725/, and this and other A-levels English exemplar writing examples can be found here: www.cambridgeinternational.org/Images/583260-cambridge-international-as-and-a-level-english-language-9093-paper-1-example-candidate-responses.pdf.

IELTS 2022 task: “You should spend about 20 minutes on this task. The pie charts show the electricity generated in Germany and France from all sources and renewables in the year 2009. Summarize the information by selecting and reporting the main features and make comparisons where relevant. Write at least 150 words.” (More detail can be found here: www.ieltsbuddy.com/sample-pie-chart.html.) For the full New Zealand IELTS information, on both the Academic Writing and General Writing exams, see: www.ielts.org/for-test-takers/test-format.

Myth 5 Chances Are, You Can’t Write

1 Example references include “Why Johnny Can’t Write” in Newsweek in 1975; “Can’t Write Can’t Spell” in The Age in 2007; “Why Johnny Can’t Write, and Why Employers are Mad” on NBC news in 2013, and “Why Kids Can’t Write” in The New York Times in 2017.

1812 For instance, two past CLA writing tasks asked students to (1) read documents about a plane and make a recommendation to a tech company about whether to purchase it; or (2) read documents about crime and make a recommendation to a mayor about the role of drug addicts in crime reduction.

3 For the full articles, see: www.washingtonpost.com/news/answer-sheet/wp/2017/04/27/why-so-many-college-students-are-lousy-at-writing-and-how-mr-miyagi-can-help/ and www.studyinternational.com/news/students-cant-write-properly-even-college-time-teach-expert/.

4 For the full article, see: www.smh.com.au/national/nsw/writing-wrongs-our-society-is-about-to-hit-a-literacy-crisis-20200917-p55wl7.html.

5 I was so flummoxed by how the sophistication point was used that I wrote an editorial in Inside Higher Education asking examiners to ignore it: www.insidehighered.com/admissions/views/2021/07/26/some-things-shouldnt-be-graded-ap-exams-opinion.

6 See the full article here: www.smh.com.au/national/how-does-grammar-help-writing-and-who-should-teach-it-20200917-p55wjc.html.

7 See more information on the scheme of assessment for AS- and A-Level English Language here: www.aqa.org.uk/subjects/english/as-and-a-level/english-language-7701-7702/scheme-of-assessment.

8 E.g. see the following AQA mark scheme example for the June 2020 “Writers’ Viewpoints and Perspectives” paper: https://filestore.aqa.org.uk/sample-papers-and-mark-schemes/2020/november/AQA-87002-W-MS-NOV20.PDF.

9 These brief details are offered here: www.acer.org/au/towa/assessment-criteria.

10 See the full American Association of Colleges and Universities Written Communication VALUE Rubric here: https://d38xzozy36dxrv.cloudfront.net/qa/content/user-photos/Offices/OCPI/VALUE/Value-Rubrics-WrittenCommunication.pdf.

11 The metaphor of control in educational criteria and outcomes starts far earlier than tertiary education. The UK English primary curriculum includes emphasis on literature and an unnamed type of English throughout its criteria. The exception under “spelling, grammar” spells out the following: “Pupils should be taught to control their speaking and writing consciously and to use Standard English. They should be taught to use the elements of spelling, grammar, punctuation and ‘language about language’ listed.” Uniquely, this example suggests conscious control, which implies conscious language awareness. (See more information about the UK primary school English curriculum here: www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-curriculum-in-england-english-programmes-of-study/national-curriculum-in-england-english-programmes-of-study.) The US NAEP Writing Assessment criteria for primary and secondary schools include the expectation that “sentence structure is well controlled,” and they emphasize context-specific appropriateness, e.g., “voice and tone are effective in relation to the writer’s purpose and audience.” But because all these criteria are framed by the NAEP’s indication that higher education and workplace settings require “correct use of the conventions of standard written English,” this register and dialect appear to be what the NAEP means by high-scored writing having “well controlled” sentence structure, voice, and tone, and “correct” grammar, usage, and mechanics. See the full Writing Framework for the 2011 NAEP here:

12 The Framework is a consensus statement from several US organizations concerned with postsecondary writing. For all of the US Framework for Success in Postsecondary Writing outcomes, see https://lead.nwp.org/knowledgebase/framework-for-success-in-postsecondary-writing/.

13 The 2017 results were never released, and the next test is scheduled for 2030. See a 2022 overview by Natalie Wexler in Forbes here: https://www.forbes.com/sites/nataliewexler/2022/01/26/we-get-national-reading-test-results-every-2-years-writing-try-20/?sh=2474d1703b9d.

14 For instance, in the US Common Core State Standards materials: (www.corestandards.org/assets/Appendix_C.pdf), the first exemplary essay closes with the following statements: “Learning to dress for particular occasions prepares us for the real world. And teens have enough pressure already without having to worry about what they are wearing.”

15 The Google Books Ngram Viewer, for instance, shows the predominance of everyone * their (e.g., everyone in their, everyone for their), which is much more common than phrases including everyone * his or her, which have been declining since 2010. (See the search at: https://books.google.com/ngrams/graph?content=everyone+*+their%2Ceveryone+*+his+or+her&year_start=1800&year_end=2019&corpus=en-2019&smoothing=3.)

16 The full writing exam includes fifteen minutes reading time and two hours to write four responses (in response to two readings). The full task of this example follows: Julia Gillard makes an entry in her diary the night before she gives this speech. Write this entry (between 120 and 150 words), basing your answer closely on the material of the speech.

The full writing exam can be found here: https://paper.sc/doc/5b4c363c6479033e61e6b725/

This and other A-Level English exemplar writing examples can be found here: https://www.cambridgeinternational.org/Images/583260-cambridge-international-as-and-a-level-english-language-9093-paper-1-example-candidate-responses.pdf

18317 Students are recommended to take about twenty minutes on the task and to write at least 150 words (more detail can be found here: www.ieltsbuddy.com/sample-pie-chart.html.) For the full New Zealand IELTS information, on both the Academic Writing and General Writing exams, see: www.ielts.org/for-test-takers/test-format.

Myth 6 You Can’t Write if You Didn’t Write Well in High School

1 For the complete list of 2016 prompts, see: https://paper.sc/doc/5b4c363c6479033e61e6b725/.

2 The NAPLAN also includes narrative tasks that require students to write a story. A recent example task begins this way: “Today you are going to write a narrative or story. The idea for your story is “The Box.” What is inside the box? How did it get there? Is it valuable? Perhaps it is alive! The box might reveal a message or something that was hidden. What happens in your story if the box is opened?” For more information on the NAPLAN writing prompts and rubrics, see: www.nap.edu.au/naplan/writing.

3 See also more public-facing coverage of teacher challenges in the Guardian in April 2017: www.theguardian.com/education/2017/apr/29/english-secondary-schools-facing-perfect-storm-of-pressures.

4 See, e.g., coverage in the Guardian in April 2017: www.theguardian.com/education/2017/apr/29/english-secondary-schools-facing-perfect-storm-of-pressures.

5 This is an overall rate, and attrition rates vary between private and public schools. See more information in the US National Association of Secondary School Principals (NASSP) January 2020 Principal Leadership Issue: www.nassp.org/publication/principal-leadership/volume-20/principal-leadership-january-2020/making-teachers-stick-january-2020/.

6 The article also notes that the news isn’t all bad: “To date, the Government’s Achievement Improvement Monitor (introduced in 2000), which rates the performance of school students against the National Literacy Benchmarks, indicates that improvement is at hand. In 2004, 97 per cent of year 3s, 93.4 per cent of year 5s and 96 per cent of year 7s met the benchmarks for writing set by the Ministerial Council on Education, Employment, Training and Youth Affairs. Figures for reading hovered around the high 80s and low 90s.” See the full article here: www.theage.com.au/education/cant-write-cant-spell-20070226-ge4ap6.html.

7 See the full article here: www.macleans.ca/education/uniandcollege/university-students-cant-spell/.

8 See the full blog post and comments here: www.cultofpedagogy.com/grammar-spelling-errors/.

1849 The use of AP courses and exams are also not equitable: access to these courses depends on schools and school districts. Students identifying as white are more likely to have access to AP courses, which are valued by colleges in student applications and can lend college credit, saving courses and money in college. In this way, courses that purport to take the place of college writing are part of “limited academic preparation by race/ethnicity” in the US (Arum, R. and J. Roksa, Academically Adrift: Limited Learning on College Campuses. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011), and also send the inaccurate message that secondary and postsecondary writing are the same.

10 Corpus linguistic analysis is computer-aided analysis of lexical and grammatical patterns across corpora, or bodies of texts, of authentic language use. For more detail on the corpora and methods, see Aull, L. (2020), How Students Write: A Linguistic Analysis. New York: Modern Language Association; Aull, L. (2015), First-year University Writing: A Corpus-based Study with Implications for Pedagogy. London: Palgrave Macmillan; Aull, L. (2019), Linguistic Markers of Stance and Genre in Upper-level Student Writing, Written Communication, 36(2), 267–95; Aull, L. (2018), Generality and Certainty in Undergraduate Writing Over Time, in Developing Writers in Higher Education: A Longitudinal Study, ed. A. R. Gere. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press. In particular, the three patterns discussed here were statistically significant patterns in A-graded writing by experienced postsecondary students in comparison with A-graded and ungraded writing by new college students.

11 Two linguistic patterns associated with cohesion in writing are cohesive words (or transition words/phrases) and cohesive moves (or rhetorical moves), described in more detail below.

Transition words include a range of transitional words and phrases that show reformulations (e.g., in other words, put another way), addition (e.g., furthermore, in addition), cause and effect (e.g., therefore), and countering (e.g., however).

Rhetorical moves are idea-steps that guide readers from what they know to what they don’t know. These moves are larger than word-level transitions; They are used within and across paragraphs. For instance, academic writers often use three moves in their introductions to create a space for their research (J. Swales (1990), Genre Analysis: English in Academic and Research Settings. Cambridge Applied Linguistics Series., Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press. xi, 260.) Move 1 introduces the territory; move 2 introduces a gap in the territory; and move 3 occupies the gap, providing the writer’s own contribution. See also: Ädel, A. (2014), Selecting Quantitative Data for Qualitative Analysis: A Case Study Connecting a Lexicogrammatical Pattern to Rhetorical Moves, Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 16, 68–80; Matsuda, P. and C. M. Tardy (2007), Voice in Academic Writing: The Rhetorical Construction of Author Identity in Blind Manuscript Review, English for Specific Purposes, 26, 235–49. For instance, academic writers often use three moves in their introductions to create a space for their research (Swales, J. (1990), Genre Analysis: English in Academic and Research Settings. Cambridge Applied Linguistics Series., Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press. xi, 260 p). Move 1 introduces the territory; move 2 introduces a gap in the territory; and move 3 occupies the gap, providing the writer’s own contribution.

12 Postsecondary writing also compresses information into noun phrases using nominalization. Nominalization is itself an example of nominalization: the word nominalization is a noun that refers to the process of nominalizing, or making a word into a noun. In another example, the word industrialization is a nominalization that refers to the process of bringing manufacturing to a place.

Myth 7 You Can’t Get a Job if You Didn’t Write Well in College

1 Links to websites and articles in order of appearance:

Penn State Smeal College of Business website (https://careerconnections.smeal.psu.edu/blog/2018/06/07/how-strong-writing-skills-benefit-your-career/)

“Benefits of Writing for Students”: Give a Grad a Go website and blog (www.giveagradago.com/news/2019/11/benefits-of-writing-for-students/448)

Tulane University, School of Professional Advancement (https://sopa.tulane.edu/blog/importance-writing-skills-workplace)

Forbes magazine article (www.forbes.com/sites/gretasolomon/2018/08/09/why-mastering-writing-skills-can-help-future-proof-your-career/?sh=3f3187615831)

Oregon State University blog (https://blog.pace.oregonstate.edu/the-importance-of-writing-in-the-workplace)

2 This unsigned story, “The Lazy Lover: A Moral Tale,” appeared in the March issue of the magazine in 1779.

3 A partial example can be found in Scotland, where public schools prepared a larger part of the population for college. See Myers, D. (1983), Scottish Schoolmasters in the Nineteenth Century: Professionalism and Politics, in Scottish Culture and Scottish Education, 1800–1980, eds. W. M. Humes and H. M Paterson, 84. Edinburgh: John Donald.

1864 See, e.g. 2020 data from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics (www.bls.gov/careeroutlook/2020/data-on-display/education-pays.htm), from the UK Government Labour Statistics (https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/graduate-labour-markets), and from the Australia Bureau of Statistics (www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/education/education-and-work-australia/latest-release).

5 For more information about the study, see https://newsroom.carleton.ca/archives/2017/04/20/carleton-study-finds-people-spending-third-job-time-email/ and Lanctot, A. M., You’ve Got Mail, But Is It Important And/Or Urgent?: An Investigation into Employees’ Perceptions of Email. 2019, doctoral dissertation, Carleton University.

6 See, e.g., tips for “not sounding silly” in emails to professors (www.insidehighered.com/views/2015/04/16/advice-students-so-they-dont-sound-silly-emails-essay) and etiquette tips for emails to lecturers/professors (www.usnews.com/education/blogs/professors-guide/2010/09/30/18-etiquette-tips-for-e-mailing-your-professor and https://thetab.com/uk/glasgow/2016/02/04/etiquette-emailing-lecturer-lecturer-8056).

7 See the full story here: www.bbc.com/news/business-58517083.

8 See the full article here: www.insidehighered.com/news/2022/12/09/state-systems-group-plans-measure-and-promote-higher-ed-value?utm_source=Inside+Higher+Ed&utm_campaign=37afa266f5-DNU_2021_COPY_02&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_1fcbc04421-37afa266f5-236367914&mc_cid=37afa266f5&mc_eid=8be683a36c.

9 For coverage of research on discrepancies between college-pay and postgraduate earnings, see, e.g., this 2021 Washington Post article: www.washingtonpost.com/education/2021/11/01/college-degree-value-major/.

10 For the full text, please see: www.thebalancecareers.com/employee-letter-and-email-examples-2059485.

Myth 8 You Can’t Write That Because Internet

1 This was, in fact, the first question someone asked me on a little island off another little island off the coast of Honduras (if language was declining because of the internet and texting), upon hearing I was an English language professor. That someone eventually became my life partner, which goes to show that even the most compelling people learn this myth, and also that there’s hope for them.

2 See the Atlantic article “The Internet Is Making Writing Worse” (www.theatlantic.com/national/archive/2013/07/internet-making-writing-worse/313199/) and the Pew Research Study (www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2020/01/200117085321.htm).

3 The full website offers advice and links with examples of what makes academic writing “formal,” “objective,” and “technical”: www.sydney.edu.au/students/writing.html.

4 See the Time article: https://time.com/5629246/because-internet-book-review/.

5 See, for instance, coverage that describes the capability and popularity of ChatGPT and educators’ concerns about it, on the BBC (www.bbc.com/news/technology-63861322), in The New York Times (www.nytimes.com/2023/01/16/technology/chatgpt-artificial-intelligence-universities.html), and in The Sydney Morning Herald (www.smh.com.au/national/this-month-the-world-changed-and-you-barely-noticed-20221214-p5c6en.html).

6 See, for instance, news coverage showing that internet use reduces study skills (www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2020/01/200117085321.htm) and news coverage discussing children and screen time (www.abc.net.au/news/2019-11-11/screen-time-and-impact-on-literacy/11681026?nw=0).

7 See the Pew Research Study (www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2020/01/200117085321.htm) and results from the first longitudinal study by the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth Center for Marketing Research (www.umassd.edu/media/umassdartmouth/cmr/studies-and-research/CollegePresidentsBlog.pdf).

8 Fun (family) fact: if you want to read about interpersonal emoji use in WhatsApp messages, read this study by my sister! Aull, B. (2019) A Study of Phatic Emoji Use in WhatsApp Communication, Internet Pragmatics, 2(2), 206–32.

9 The third most-liked tweet of 2021 is a kissing-face emoji accompanied by a selfie, tweeted by South Korean singer and songwriter Jungkook, member of the K-pop group BTS, with over 3.2 million likes. The most retweeted tweet of 2021 was also linked to BTS; the BTS group account tweeted the hashtags #StopAsianHate #StopAAPIHate. Both examples show the use of informal digital writing patterns, or emojis and hashtags, to convey interpersonal aims and to connect cohesively with other messages and language users.

10 Find the full irishtimes.com article in the newspaper’s TV & Radio culture section (www.irishtimes.com/culture/tv-radio-web/harry-and-meghan-the-union-of-two-great-houses-the-windsors-and-the-celebrities-is-complete-1.4504502).

11 For the full New York Times article, see: www.nytimes.com/2021/04/19/well/mind/covid-mental-health-languishing.html

18812 See, e.g., klaviyo.com’s top five campaigns here: www.klaviyo.com/blog/top-email-and-sms-campaign-examples; see pure360.com’s top 10 here: https://www.pure360.com/a-look-back-10-emails-from-2021-that-were-loving-and-why/.

13 See the full article here: www.thelancet.com/article/S0140-6736(20)30183-5/fulltext.

Conclusion: Writing Continuum, Language Exploration

1 The full podcast about Haskell’s book Sounds Wild and Broken can be found here: https://theamericanscholar.org/the-sound-of-science/.