Reference Mancini, Agostiniani and MarcheseMancini (2019) provides a useful summary of the history of the spelling <xs> for <x>. The earliest example in a Latin inscription is exstrad (twice) in the SC de Bacchanalibus (CIL 12.581) of 186 BC,Footnote 1 although two instances of faxsit in testimonia of the Laws of the Twelve Tables are argued by Mancini to reflect an edition carried out by Sextus Aelius Paetus, curule aedile in 200 BC, consul 198, and censor in 194.Footnote 2 In addition, the Marrucinian ‘Bronze of Rapino’, datable to the second half of the third century BC, has lixs ‘law’ < *lēg-s. In a corpus of inscriptions from this period until 30 BC, Mancini counts 135 occurrences of <xs> beside 1,310 of <x> (<xs> thus making up 9% of the total).

From the Augustan period it more or less dies out in ‘official’ inscriptions, with occasional archaising usages in juridical inscriptions in the first and, once, second century AD. However, it continues to be used in other inscriptions until a late period, although always making up a small minority compared to uses of <x>. Mancini compares the 655 examples of uixsit ‘(s)he lived’ with 62,946 cases of uixit (1%); likewise he finds 497 cases of uxsor beside 6,858 of uxor (7%).Footnote 3 To what extent these figures are reliable as to the rate at which <xs> was used is unclear. The EDCS with which he carried out these searches throws up plenty of false positives, and with such great numbers not much checking can have been carried out. As an additional contribution, I carried out searches for sexaginta and sexsaginta, and checked them for accuracy. The former appeared in 71 inscriptions, the latter in 14 (16%), giving a much larger minority for <xs>.Footnote 4 The variation may reflect the smaller numbers of sexaginta in inscriptions, or genuine lexical variation as to use of <xs> versus <x> (although no particular pattern arises on this front from my investigation of the corpora below).

The spelling <xs> is barely mentioned by the writers on language, except for a brief hint by Cornutus and more explicit statements by Caesellius and Terentius Scaurus that <xs> should only be used in compounds consisting of the preposition ex plus a word beginning with /s/. There is no suggestion that <xs> is old-fashioned, just incorrect:

‘exsilium’ cum s: “ex solo” enim ire, quasi ‘exsolium’ …

Exsilium with s: because it comes from ex solo, as though it were exsolium …

quaecumque uerba primo loco ab s littera incipient, ea cum praepositione ‘ex’ composita litteram eandem s habere debebunt … cetera, quae simplicia sunt et non componuntur, sine ulla dubitatione x tantum habebunt, ut ‘uixi’, ‘dixi’, ‘uexaui’, ‘faxim’, ‘uxor’, ‘auxilium’, ‘examen’, ‘axis’ et ‘exemplum’.

Any word which begins with s ought to maintain the s when preceded by the preposition ex …Footnote 5 Other words, which are simplicia and not compounds, should have, without any doubt, only x, such as uixi, dixi, uexaui, faxim, uxor, auxilium, examen, axis, and exemplum.

item cum ‘exsul’ et ‘exspectatus’ sine ‘s’ littera scribuntur, cum alioqui adiecta ea debeant scribi, quoniam similiter ‘solum’ ‘spectatus’que dicatur, et adiecta praepositione saluum esse illis initium debeat.

Likewise when exsul and exspectatus are written without s, when on the contrary they should be written with it, since one says solum and spectatus alike, and their initial letter ought to be preserved when the preposition is added.

Terentius Scaurus also mentions people who argue that words ending in <x> should have <xs>; again this is described as incorrect rather than old-fashioned:

similiter peccant et qui ‘nux’ et ‘trux’ et ‘ferox’ in <‘s’> nouissimam litteram dirigunt, cum alioqui duplex sufficiat, quae in se et ‘s’ habet.

Likewise those who direct an additional s onto the end of nux, trux and ferox, when, on the contrary, the double letter (x) is enough, which contains s within it.

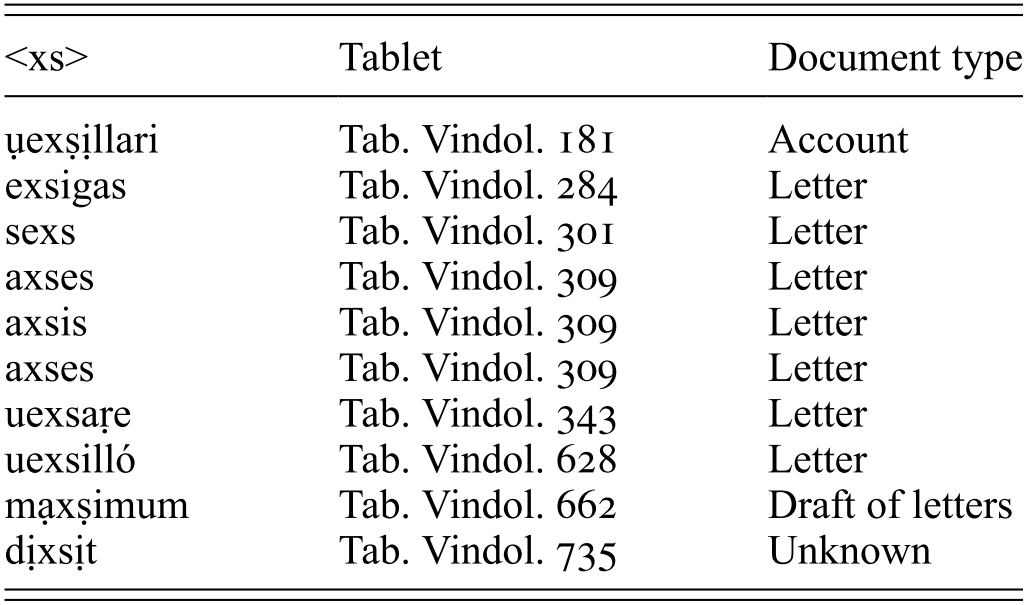

The marginality of the spelling <xs> is confirmed in my corpora, although with some variation.Footnote 6 In the Vindolanda tablets (see Table 19) I find 10 certain instances of <xs> vs 66 of <x>.Footnote 7 Reference Mancini, Agostiniani and MarcheseMancini (2019: 27) reproves Reference AdamsAdams (1995: 90) for the statement that ‘xs is commonly written for x in the tablets’, but at 13%, <xs> does appear at a higher rate than uixsit and uxsor in Mancini’s calculations from the whole corpus of Latin inscriptions. Adams sees the use of <xs> as formal or archaising, while Reference Mancini, Agostiniani and MarcheseMancini (2019: 28) argues that it is ‘informal and bureaucratic’ (informale e cancelleresco).Footnote 8 This disagreement may be due to a different perspective on the status of the Vindolanda tablets. Mancini is comparing the presence of <xs> in ‘everyday documents’ such as the tablets from Vindolanda, London and those of Caecilius Jucundus from Pompeii, alongside papyrus letters, with its absence in public epigraphy. By comparison, Adams is more focussed on the usages of individuals in the Vindolanda tablets, and variation between genres within the corpus.

Table 19 <xs> at Vindolanda

| <xs> | Tablet | Document type |

|---|---|---|

| ụexṣịllari | Tab. Vindol. 181 | Account |

| exsigas | Tab. Vindol. 284 | Letter |

| sexs | Tab. Vindol. 301 | Letter |

| axses | Tab. Vindol. 309 | Letter |

| axsis | Tab. Vindol. 309 | Letter |

| axses | Tab. Vindol. 309 | Letter |

| uexsaṛe | Tab. Vindol. 343 | Letter |

| uexsilló | Tab. Vindol. 628 | Letter |

| mạxṣimum | Tab. Vindol. 662 | Draft of letters |

| dịxsịt | Tab. Vindol. 735 | Unknown |

Clearly, the letters found at Vindolanda are ‘informal’ relative to public epigraphy, but we do have a hint that they could be marked out from other genres by the tendency for apices to be used preferentially in letters as opposed to other types of text (see pp. 235–6). And in fact, apices and <xs> co-occur in Tab. Vindol. 628. The sequence <xs> also tends to appear in letters, which provide 8 out of 9 instances in which the genre of the text is recognisable.Footnote 9 This compares with <x>, of which 37/65 instances appear in letters (one document is of uncertain genre). The numbers are too small, however, to be sure that <xs> does correlate with letters.Footnote 10 The use of <xs> is also not necessarily consistent within a text: 301 has explices beside sexs,Footnote 11 and in the letter of Octavius (343), apart from uexsaṛe, there are 6 instances of <x>, consisting of dixi and 5 examples of the preverb ex-.

Adams also observes that the three examples of <xs> in 309 appear alongside the spelling of mīsī ‘I sent’ as missi, ṃissi, in a text whose spelling is otherwise standard. And in fact there are further connections between use of <xs> and <ss>. The same hand that writes 181, which contains ụexṣịllari, also writes 180, another account, and 344, a letter which enables the author to be identified as a civilian trader. 180 (which has <x> in ex) also has <ss> in ussus for ūsūs ‘uses’. 344 has no instances of <x(s)> but writes comississem for comīsissem ‘I had committed’. Given the civilian status of the author, it may be that the spelling he or his scribe uses is the result of different training from that of the scribes in the army. In 343, the spelling <ss> is also attested indirectly in the form nissi for nisi ‘if not’ (see p. 185). It is striking that 5 of the 22 instances of <ss> in the Vindolanda tablets occur in documents which also have <xs>. In 343, apart from using <xs> and <ss>, the writer is also characterised by the rare use of <k> in a word other than k(alendae) and cārus ‘dear’: karrum and ḳarro for carrum ‘wagon’.

The spelling <xs>, therefore, appears in texts which use other spellings which might be considered old-fashioned. It is reasonable to suppose that <xs> may have had a similar value. From a sociolinguistic perspective, <xs> appears in letters from a range of backgrounds. In 301, the writer Severus is a slave, writing to a slave of the prefect Flavius Genialis in his own hand. The author of 284 is probably a decurion, writing to the prefect Flavius Cerialis, and 628 is also a letter to Cerialis from a decurion called Masclus (but both are probably using scribes; note the use of apices in the latter). The author of 309 (Metto?) is probably a civilian trader, though most of the letter is written in another hand. Very little remains of 662 or 735. All of these show otherwise standard spelling, as far as we can tell (other than Masclus for Masculus in 628, with a ‘vulgar’ syncope; but since this is the author’s name this does not necessarily suggest a lower educational standard on the part of the writer).Footnote 12

On the other hand, the writer of 343, whose author was Octavius, who may have been ‘a civilian entrepreneur and merchant, or a military officer responsible for organising supplies for the Vindolanda unit’, according to the editors, combines use of <xs>, <ss> and <k> with the substandard spellings <e> for <ae> in illec for illaec ‘those things’, arre for arrae ‘pledge’, que for quae ‘which’, male for malae ‘bad’, <ae> for <e> in ṃae for mē ‘me’, and <i> for <ii> in necessari for necessariī ‘necessary’. The letter 344 contains only standard spelling, but the accounts 180 and 181, by the same writer, do include a few substandard spellings: bubulcaris for bubulcāriīs ‘ox-herds’, turṭas for tortās ‘twisted loaves’ (both 180), emtis for emptīs, balniatore for balneātōre, and Ingenus for Ingenuus (all 181).

Overall, Adams’ view that <xs> is formal or archaising, within the context of the Vindolanda tablets, receives some support from its association with other old-fashioned spellings, in the form of <ss> for <s> by three different writers, and with <k> in one of them. However, we cannot be sure that its greater frequency in letters is due to the relatively more formal status of these than other types of document. The writers who include <xs> in their texts all probably belong to the sub-elite, consisting of slaves, scribes and perhaps civilian traders. It is found in texts which demonstrate both standard and substandard spelling. It is conceivable that <xs> is not actually a major part of the scribal tradition of the army itself, since at least 4 of the instances come from letters whose authors were civilians (5 if Octavius, the author of 343, was also a civilian), and only 284 (1 example) and 628 (1 example) seem to have definitely been written by military personnel. But of course, military scribes, and/or education in writing, may have been available also to non-military personnel.

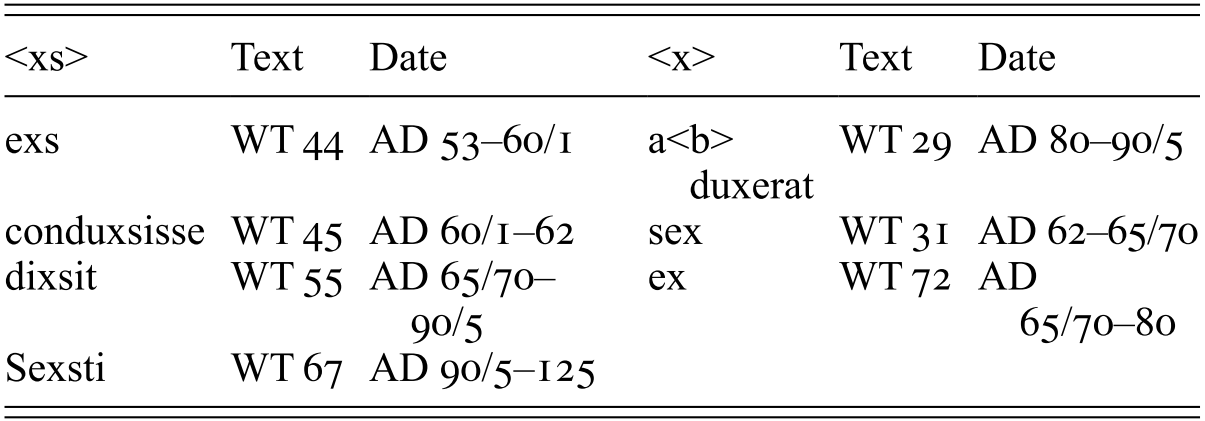

Two of the other corpora are particularly noteworthy in terms of use of <xs>. One is the London tablets, which contain 4 examples of <xs> and only 3 of <x> (see Table 20). The spelling of WT 44 and 45 is standard; WT 55 is substandard (see p. 264), and also uses another old-fashioned spelling, <ss> after a long vowel in u]s{s}uras and promis{ṣ}it; the spelling of WT 67 is also substandard (see p. 264). As for the tablets which have <x>, WT 29 has substandard features (see p. 264), along with 2 instances of <ss> in [o]cassionem for occāsiōnem ‘occasion’ and (hypercorrect) messibus for mēnsibus ‘months’. WT 31 has standard spelling except for Aticus for Atticus, which may simply be a haplography. WT 72 has Butu for Butum, but the reading is difficult and the word is at the end of a line anyway so may reflect lack of space. What other text there is has standard spelling (n.b. Ianuarium) and a hypercorrect use of <ss> in ceruessam. It seems that in these tablets <xs> can correlate with both standard and substandard spelling, and with <ss>, while <x> is found with substandard spelling and <ss>, but there is hardly enough evidence to draw particular conclusions from this other than that <xs> is remarkably common.

Table 20 <xs> and <x> in the London tablets

| <xs> | Text | Date | <x> | Text | Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| exs | WT 44 | AD 53–60/1 | a<b>duxerat | WT 29 | AD 80–90/5 |

| conduxsisse | WT 45 | AD 60/1–62 | sex | WT 31 | AD 62–65/70 |

| dixsit | WT 55 | AD 65/70–90/5 | ex | WT 72 | AD 65/70–80 |

| Sexsti | WT 67 | AD 90/5–125 |

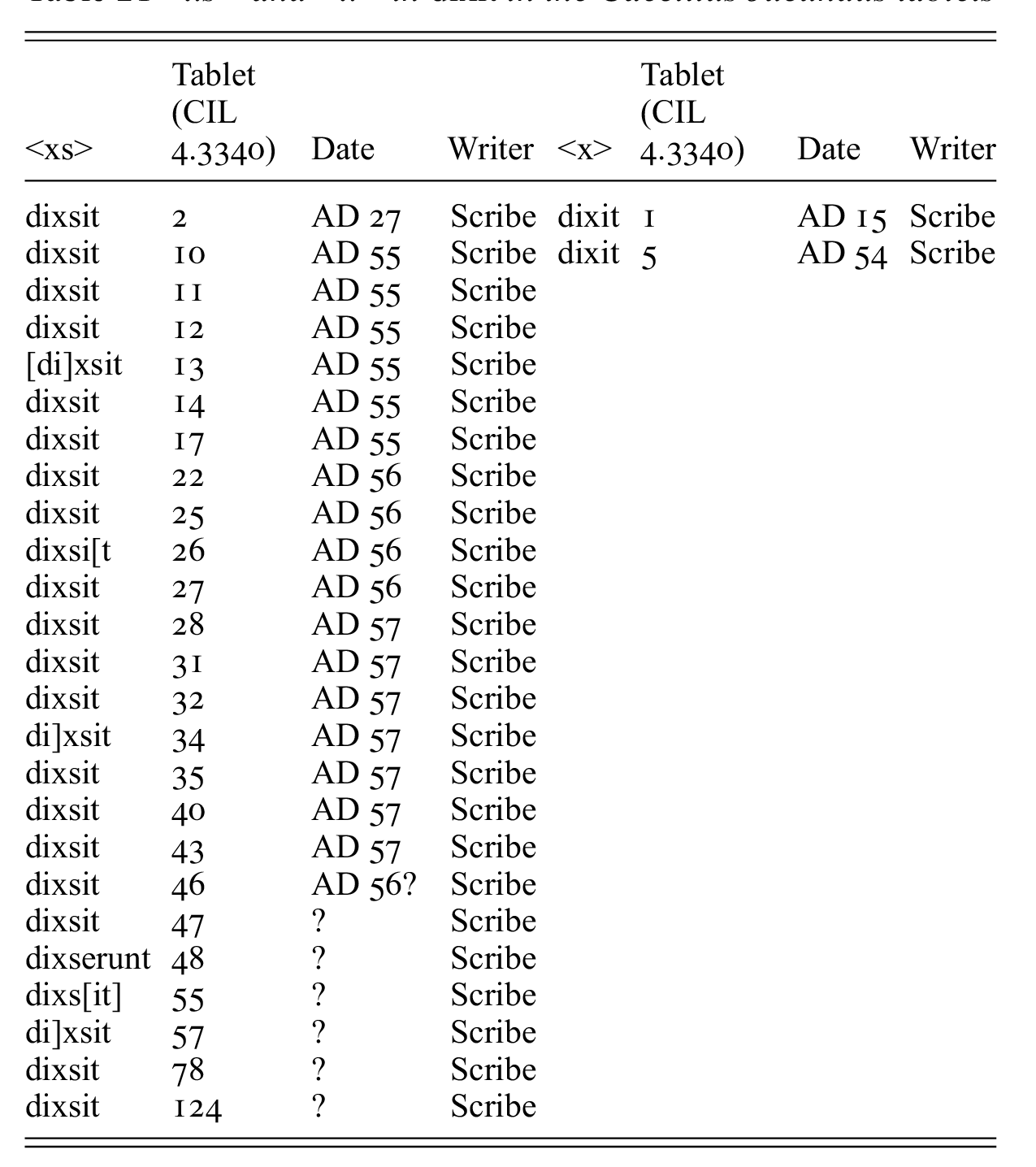

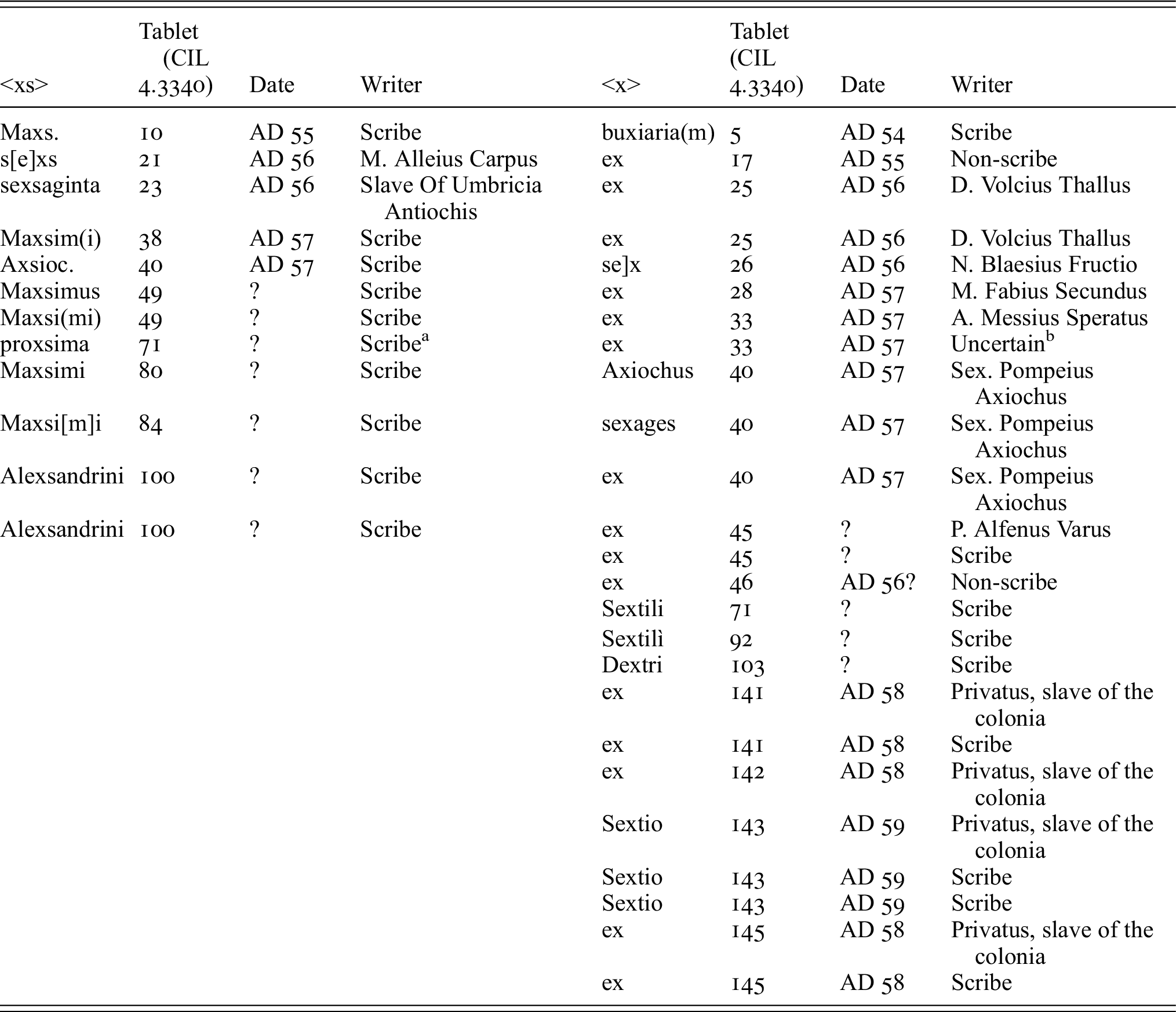

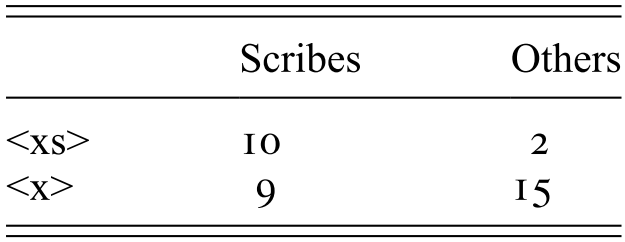

The other corpus is the tablets of Jucundus, in which <xs> is characteristic of the scribes, who use it 35 times to 11 instances of <x>, whereas the other writers have 2 examples of <xs> and 15 of <x> (see Table 21 and Table 22). In fact, there seem to be three important factors which apply to the use of <xs>. 25 of the examples of <xs> occur in the word dixsit (and dixserunt) in tablets concerning auctiones, which contain the formulas habere se dixsit … ‘(s)he said that (s)he has [a certain amount of money]’ and accepisse se dixit/dixserunt … ‘(s)he/they said that (s)he/they has/have received [a certain amount of money]’, which are always written by scribes. The difference between use of <xs> in dīxit/dīxē̆runt and in other words by the scribes is statistically significant.Footnote 13 An explanation for this might be that the spelling with <xs> was felt to be particularly appropriate for this word because it appears in a formulaic context.Footnote 14 However, even if we leave dīxit/dīxē̆runt out of the equation (and not including one uncertain case), there is still a statistically significant difference between the rates of use of <xs> and <x> in other words by scribes (10:11) and other writers (2:15); see Table 23.Footnote 15 Tablet 1 is the earliest of the tablets, and perhaps reflects a slightly different orthographic training: as well as using <x> in dixit, it also uses the spelling pequnia versus the pecunia found uniformly in the other tablets.

Table 21 <xs> and <x> in dixit in the Caecilius Jucundus tablets

| <xs> | Tablet (CIL 4.3340) | Date | Writer | <x> | Tablet (CIL 4.3340) | Date | Writer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dixsit | 2 | AD 27 | Scribe | dixit | 1 | AD 15 | Scribe |

| dixsit | 10 | AD 55 | Scribe | dixit | 5 | AD 54 | Scribe |

| dixsit | 11 | AD 55 | Scribe | ||||

| dixsit | 12 | AD 55 | Scribe | ||||

| [di]xsit | 13 | AD 55 | Scribe | ||||

| dixsit | 14 | AD 55 | Scribe | ||||

| dixsit | 17 | AD 55 | Scribe | ||||

| dixsit | 22 | AD 56 | Scribe | ||||

| dixsit | 25 | AD 56 | Scribe | ||||

| dixsi[t | 26 | AD 56 | Scribe | ||||

| dixsit | 27 | AD 56 | Scribe | ||||

| dixsit | 28 | AD 57 | Scribe | ||||

| dixsit | 31 | AD 57 | Scribe | ||||

| dixsit | 32 | AD 57 | Scribe | ||||

| di]xsit | 34 | AD 57 | Scribe | ||||

| dixsit | 35 | AD 57 | Scribe | ||||

| dixsit | 40 | AD 57 | Scribe | ||||

| dixsit | 43 | AD 57 | Scribe | ||||

| dixsit | 46 | AD 56? | Scribe | ||||

| dixsit | 47 | ? | Scribe | ||||

| dixserunt | 48 | ? | Scribe | ||||

| dixs[it] | 55 | ? | Scribe | ||||

| di]xsit | 57 | ? | Scribe | ||||

| dixsit | 78 | ? | Scribe | ||||

| dixsit | 124 | ? | Scribe |

Table 22 <xs> and <x> in other words in the Caecilius Jucundus tablets

| <xs> | Tablet (CIL 4.3340) | Date | Writer | <x> | Tablet (CIL 4.3340) | Date | Writer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maxs. | 10 | AD 55 | Scribe | buxiaria(m) | 5 | AD 54 | Scribe |

| s[e]xs | 21 | AD 56 | M. Alleius Carpus | ex | 17 | AD 55 | Non-scribe |

| sexsaginta | 23 | AD 56 | Slave Of Umbricia Antiochis | ex | 25 | AD 56 | D. Volcius Thallus |

| Maxsim(i) | 38 | AD 57 | Scribe | ex | 25 | AD 56 | D. Volcius Thallus |

| Axsioc. | 40 | AD 57 | Scribe | se]x | 26 | AD 56 | N. Blaesius Fructio |

| Maxsimus | 49 | ? | Scribe | ex | 28 | AD 57 | M. Fabius Secundus |

| Maxsi(mi) | 49 | ? | Scribe | ex | 33 | AD 57 | A. Messius Speratus |

| proxsima | 71 | ? | ScribeFootnote a | ex | 33 | AD 57 | UncertainFootnote b |

| Maxsimi | 80 | ? | Scribe | Axiochus | 40 | AD 57 | Sex. Pompeius Axiochus |

| Maxsi[m]i | 84 | ? | Scribe | sexages | 40 | AD 57 | Sex. Pompeius Axiochus |

| Alexsandrini | 100 | ? | Scribe | ex | 40 | AD 57 | Sex. Pompeius Axiochus |

| Alexsandrini | 100 | ? | Scribe | ex | 45 | ? | P. Alfenus Varus |

| ex | 45 | ? | Scribe | ||||

| ex | 46 | AD 56? | Non-scribe | ||||

| Sextili | 71 | ? | Scribe | ||||

| Sextilì | 92 | ? | Scribe | ||||

| Dextri | 103 | ? | Scribe | ||||

| ex | 141 | AD 58 | Privatus, slave of the colonia | ||||

| ex | 141 | AD 58 | Scribe | ||||

| ex | 142 | AD 58 | Privatus, slave of the colonia | ||||

| Sextio | 143 | AD 59 | Privatus, slave of the colonia | ||||

| Sextio | 143 | AD 59 | Scribe | ||||

| Sextio | 143 | AD 59 | Scribe | ||||

| ex | 145 | AD 58 | Privatus, slave of the colonia | ||||

| ex | 145 | AD 58 | Scribe |

a Page 2 of this tablet, on which proxima occurs, has lost almost all its writing, but on the basis that there are nine witnesses, this tablet must be the record of an auctio, in which case the inner writing is always carried out by a scribe (Reference AndreauAndreau 1974: 18–19).

b Page 2 of this tablet contains the chirographum of A. Messius Speratus, which seems to end on that page; on page 3, on which ex occurs, we then get what appears to be an incomplete version of the auctio formula, which is in the third person, and hence would be expected to be written by a scribe. However, the spelling is substandard (abere for habēre ‘to have’, Mesius for Messius, Pompes for Pompeīs), as in the chirographum, and it looks as though the writer may have started off using the first person: Zangemeister prints abere m.., and comments ‘inchoasse videtur aliam constructionem: me (scripsi vel dixi)’. It seems more likely that for some reason Messius also wrote this page.

Table 23 Use of <xs> and <x> by scribes and others in the Caecilius Jucundus tablets

| Scribes | Others | |

|---|---|---|

| <xs> | 10 | 2 |

| <x> | 9 | 15 |

It is difficult to identify a cohesive pattern in the use of <xs> across the corpora. On the one hand, the scribes of the Caecilius Jucundus tablets heavily favour <xs> at a rate of 69%, or 53% if we assume that dix(s)it is a special case, which compares significantly with the usage of the other writers, who use <xs> only 12% of the time. By comparison, the typologically, geographically and chronologically similar corpora TPSulp. and TH2 demonstrate an avoidance of <xs>, on the part of both scribes and others. The former has a single use of <xs> in sexsṭum (TPSulp. 46, scribe), compared to 87 other examples of <x> (and one case of <cs> in Ạḷẹcsì, TPSulp. 90). The latter has 32 instances of <x> and none of <xs>.

In Kropp’s corpus of curse tablets there are 19 instances of <xs> overall, and 131 of <x>, giving a rate of 13%. 7 of these are in texts dated to the second and first centuries BC; Table 24 gives all examples from the first century AD onwards. All of these tablets except 3.2/26 feature substandard spellings; 3.2/24 and 3.22/3 also have (hypercorrect) <ss> in nissi for nisi ‘if not’.

Table 24 <xs> in the curse tablets

| Tablet | Date | Location | |

|---|---|---|---|

| exsemplaria | Kropp 2.2.1/1 | AD 100–150 | Hispania Baetica |

| Exsactoris | Kropp 3.2/9 | Third century AD (?) | Aquae Sulis |

| paxsa | Kropp 3.2/24 | Third–fourth century AD | Aquae Sulis |

| exsigatur | Kropp 3.2/26 | Second–third century AD | Aquae Sulis |

| paxsam | Kropp 3.2/54 | Third–fourth century AD | Aquae Sulis |

| exsigat | Kropp 3.22/3 | Second–fourth century AD | Uley |

| exsigat | Kropp 3.22/3 | Second–fourth century AD | Uley |

| maxsime | Kropp 5.1.3/1 | First–second century AD | Germania Superior |

| uxsor | Kropp 5.1.4/8 | First half of the second century AD | Germania Superior |

| uxso[r] | Kropp 5.1.4/8 | First half of the second century AD | Germania Superior |

| Maxsumus | Kropp 5.1.4/10 | First half of the second century AD | Germania Superior |

| proxsimis | Kropp 7.5/1 | c. AD 150 | Raetia |

The Isola Sacra inscriptions contain a few instances of <xs>, with 5 compared to 105 of <x>. 1 example of uixsit (IS 258) compares with 43 instances of the perfect stem of uīuō with <x>, and the 1 example of uxsori (IS 98) with 7 of uxor (though this does give rates of 2% and 14% respectively, both twice as frequent as the rates found by Mancini in the epigraphic evidence more generally). Strikingly, the word most frequently spelt with <xs> is the cognomen Fēlix, with 3 instances of <xs> (IS 44, 225, 312) versus 4 of <x>. Only one of the inscriptions containing <xs> also contains a substandard spelling, in the form of comparaberunt for comparāuē̆runt (IS 312). The same inscription also has <x> in Maxima.

The other corpora mostly show no or little use of <xs>. The only instance of <xs> in the Bu Njem ostraca is sexsagi[nta (O. BuNjem 78), in a letter written by a soldier called Aemilius Aemilianus, whose spelling is not as bad as in some of the other texts, but does include some substandard features (see p. 263). They also include the non–old-fashioned transmisi, which appears in all the letters, but this spelling probably comes from the template that Aemilianus was using (Reference AdamsAdams 1994: 92–4). There are 24 instances of <x> in other ostraca. At Dura Europos <xs> is entirely absent, and there are more than a hundred cases of <x>. Vindonissa has no examples of <xs>, but only 3 of <x>. The graffiti from the Paedagogium have 25 instances of <x> and none of <xs>.

Within the corpus of letters, <xs> is interestingly absent from those of Claudius Tiberianus, despite the preponderance of both old-fashioned and substandard spellings (although there are only 8 instances of <x>, 4 each in P. Mich VIII 467/CEL 141 and 472/147). The letters definitely attributed to Rustius Barbarus also have 9 instances of <x> (CEL 73, 74, 77, 78) and none of <xs>, although CEL 80, which belongs to the same cache but may not have been written by Rustius, has exsigas for exigās ‘you should take out’. Of the other letters, the private letter of the slave Suneros (CEL 10), of Augustan date, has 3 instances of <xs> (on Suneros’ spelling, see pp. 10–11). There is then 1 in CEL 88 (probably first century AD), and CEL 140, a papyrus copy of an official letter of probatio from Oxyrhynchus (AD 103), which also contains three examples of <x>, and which has otherwise standard spelling (including <k> in karissiṃ[e]).