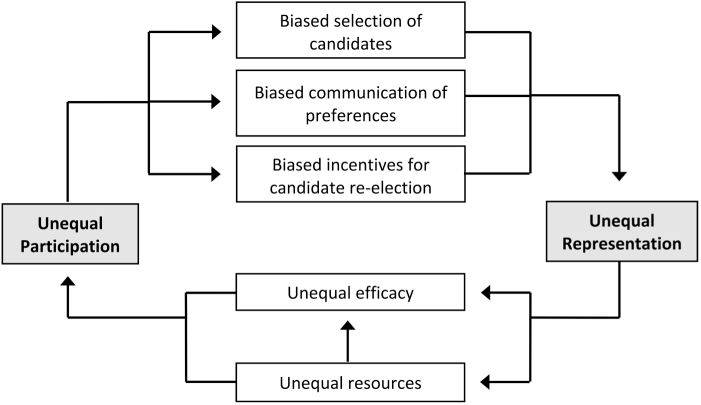

What explains unequal representation in contemporary democracies? In the wake of rising economic inequality, a recent literature has cumulated evidence that legislators in representative institutions, ranging from the US Congress to legislative assemblies in Europe and Latin America, are more responsive to (or more congruent with) the preferences of high-income constituents and business interests than to the preferences of those with average incomes and particularly the poor (e.g., Bartels Reference Bartels2008; Elsässer, Hense, and Schäfer Reference Elsässer, Hense and Schäfer2017; Gilens Reference Gilens2012; Gilens and Page Reference Gilens and Page2014; Lupu and Warner Reference Lupu and Warner2022a; Mathisen et al., volume; but see Elkjær and Iversen Reference Elkjær and Iversen2020). However, there is no consensus on the main mechanisms driving unequal representation. Surprisingly divergent views are combined with only limited evidence on the impact of organized interests on political inequality in legislatures.

In this chapter, we start by reviewing the scholarly debate and identify a central area of disagreement about the relative importance of interest groups and the mechanism through which they shape substantive political inequality. Then, we present a synthetic model that captures a representative democracy with organized interests that can seek to influence policy through electoral selection and postelectoral lobbying. We use the model to derive positive implications on the context-varying nature of interest group influence and to clarify the challenges faced by scholars trying to uncover interest group influence and to unbundle competing mechanisms using empirical observations.

Broadly speaking, a fundamental difference among theories of unequal democracy is their relative emphasis on electoral selection or postelectoral influence as drivers of unequal representation. Prominent explanations that take an electoral selection perspective include partisan differences and descriptive representation (Bartels Reference Bartels2008; Carnes Reference Carnes2013; Carnes and Lupu Reference Carnes and Lupu2015; Curto-Grau and Gallego, this volume; Mathisen et al., this volume; Rhodes and Schaffner Reference Rhodes and Schaffner2017). This analytical perspective focuses scholars’ attention on explaining unequal influence over election outcomes (e.g., based on campaign finance, electoral laws, organized labor, or voter psychology). Alternative explanations highlight the importance of postelectoral channels of influence and focus on lobbying, broadly construed (Flavin Reference Flavin2015b; Hacker and Pierson Reference Hacker and Pierson2010; Hertel-Fernandez, Mildenberger, and Stokes Reference Hertel-Fernandez, Mildenberger and Stokes2019; Kelly et al. Reference Kelly, Morgan, Witko and Enns2019).

Interest groups may influence political representation through both channels, electoral selection and postelectoral influence. But we know little about the relative importance of these two channels. Moreover, there is no agreement on the overall contribution of interest groups to political inequality. A better understanding of possible mechanisms provides foundations for studying the total impact.

One the one side, organized groups that represent business interests and high-income professionals are an important explanation for why policy outcomes deviate substantively from the preferences of average citizens. This perspective is called Biased Pluralism (Gilens and Page Reference Gilens and Page2014). While direct tests are still rare, the study of Gilens and Page (Reference Gilens and Page2014) covers nearly two thousand policy issues in the United States. It concludes that organized interests have a substantial impact on public policy, beyond the preferences of average citizens and economic elites, and that this is especially pronounced for business-oriented groups. Related research on legislative voting rather than policy adoption uses an instrumental-variable approach and finds evidence that labor unions can dampen the pro-rich bias in the US Congress (Becher and Stegmueller Reference Becher and Stegmueller2021). The view that organized interests matter for political equality is of course not restricted to American politics. Mancur Olson’s theory of collective action implies that narrow, concentrated interests are more likely to be represented in the interest group universe than broad-based groups of citizens (Olson Reference Olson1965). It is not hard to find scholars of contemporary democracy in Europe who, after looking at the available data, are worried about biased pluralism. For example, recent comparative research shows that European campaign finance systems are unequal, benefiting the rich and corporations more than the poor through tax exemptions and other rules, and that higher campaign spending is linked to electoral results (Cagé Reference Cagé2020).

On the other side, the quantitative empirical literature on the role of money in politics has grappled with the difficulty of showing that interest groups’ financial contributions affect legislative votes. Reviewing dozens of roll-call studies on the link between interest group contributions and legislative voting in the United States, Ansolabehere, Figueiredo, and Snyder (2003: 116) conclude that the evidence that financial contributions to candidates affect their votes “is rather thin.” Rather, based on their own analysis they conclude that “Legislators’ votes depend almost entirely on their own beliefs and the preferences of their voters and their party.” They add the methodological recommendation that scholars trying to assess the impact of money on votes using observational data should include legislator fixed effects to control for legislators’ own preferences, party, and constituency influence. By doing so, scholars are implicitly or explicitly trying to isolate a postelectoral channel of influence. However, this strategy can be problematic and lead to misleading inferences when electoral selection and postelectoral influence are complements.

We argue that electoral selection and postelectoral influence are likely to go hand in hand in polarized environments. Ignoring this complementarity, researchers may wrongly conclude that only electoral politics matters as a channel through which interest groups affect political equality in legislatures. This issue matters both for tests of positive theories of unequal democracy as well as normative evaluations. Without a better understanding of mechanisms, it remains difficult to devise strategies to mitigate substantive political inequality against the backdrop of economic inequality and populist challenges to democratic institutions.

We set forth our argument using a simple formal model that is then used to generate simulated legislatures. It captures a two-stage political process with an electoral and a postelectoral stage. The model assumes a political process where electoral influence and postelectoral influence are not perfect substitutes. An organized interest – whether pro-poor or pro-rich – aiming to shape policy has to first ensure that their preferred politician is elected. But the story does not end on election night. Legislators have a constrained agenda and will carefully choose which issues to prioritize even among those they principally agree with. So the organized group will also have to lobby (friendly) legislators (Austen-Smith and Wright Reference Austen-Smith and Wright1994; Hall and Deardorff Reference Hall and Deardorff2006).

Our model illuminates how the strategies of organized interests vary across context. When party polarization is relatively low, they can focus on swaying legislators through postelectoral lobbying. Increasing polarization incentivizes organized interests to focus some of their energy on helping to select like-minded politicians. However, lobbying will not be fully substituted by electioneering. Rather, when polarization is high, and with politicians facing competing demands, organized interests will have to engage in both activities. This leads to an important but largely neglected challenge for empirical research on unequal representation (and the related, but largely separate, literature on lobbying): what can be learned about mechanisms from the data alone might be limited by the strategic actions of political actors.

The problem of analyzing mechanisms is not simply due to confounding or omitted variable bias. Assume that a researcher can identify the causal effect of the group on legislative behavior (e.g., via an exogenous or instrumented measure of group strength, or a natural experiment). The key question then is how much of the treatment effect is due to electoral selection of a friendly legislator versus postelectoral lobbying. To empirically illustrate this point, we simulate thousands of possible legislatures arising from a known data generating process (our theoretical model) where without postelectoral lobbying legislators would not support an interest group’s preferred policy. We then apply statistical models commonly used in the literature and show that researchers risk drawing incorrect conclusions from such analyses, overstating the relevance of elections as a channel through which groups affect legislative responsiveness. Furthermore, we illustrate the issue using roll-call votes in the US House of Representatives.Footnote 1

Empirical research on lobbying usually faces the problem that postelectoral effort cannot be inferred from observable data. However, as we show in this chapter, our conclusion still stands even when researchers can fully observe postelectoral effort (or correct for the known lack of reliability of a measure). The reason is that the group lobbies friendly legislators. In equilibrium, the selection of a friendly legislature and lobbying can be highly (but not perfectly) correlated. Empirically, this leads to a form of simultaneity bias. As a result, based on standard empirical analyses, scholars may erroneously conclude that all that matters for unequal representation is electoral politics. Again, this empirical problem exists even though scholars can causally estimate the total effect of group power on legislative responsiveness.

Income and Legislative Responsiveness

The idea that all citizens should count approximately equally in the political process underpins various normative theories of democracy since antiquity (Müller Reference Müller2021). Political equality is conceived as the “equal advancement of interests” (Christiano Reference Christiano2008: 95) and is about substantive or de facto representation, not just equal political rights. This is what Dahl (Reference Dahl1971) calls equal responsiveness and the social choice literature calls the anonymity axiom. Political equality is a yardstick, not a prediction. Several positive theories of democratic politics suggest that pervasive socioeconomic inequalities can limit equality in policymaking. For example, interest groups’ monetary contributions can influence postelectoral policymaking (Grossman and Helpman Reference Grossman and Helpman2001) as well as electoral outcomes (Cagé Reference Cagé2020). In the wake of rising economic inequality (Lupu and Pontusson, this volume; Piketty Reference Piketty2014), political scientists and other social scientists have paid increasing attention to the implications of economic inequality for substantive political equality.

Building on pioneering research on the US Senate (Bartels Reference Bartels2008) and policy adoption in the United States (Gilens Reference Gilens2012), numerous studies have found evidence that elected policymakers in legislative assemblies are more responsive to the preferences of relatively rich constituents at the expense of middle-income and poor constituents (e.g., Elsässer, Hense, and Schäfer Reference Elsässer, Hense and Schäfer2017; Gilens Reference Gilens2016; Hertel-Fernandez, Mildenberger, and Stokes Reference Hertel-Fernandez, Mildenberger and Stokes2019; Kalla and Broockman Reference Kalla and Broockman2016a; Lupu and Warner Reference Lupu and Warner2022a; Mathisen et al. in this volume; Peters and Ensink Reference Peters and Ensink2015; Rigby and Wright Reference Rigby and Wright2013). Responsiveness here refers to the relationship between the opinions of constituents differentiated by income and legislative actions of officeholders, usually legislative votesFootnote 2, or the relationship between national public opinion differentiated by income and policy outcomes. When policy questions are polarized by income, many of these studies suggest that the views of the rich matter more, whereas the views of the poor matter little or not at all (but see Brunner, Ross, and Ebonya Reference Brunner, Ross and Ebonya2013; Elkjær and Iversen Reference Elkjær and Iversen2020). Perhaps not surprisingly, populist parties and politicians have capitalized on the perception that democracy favors the affluent (Müller Reference Müller2021).

The degree and relevance of unequal responsiveness is a matter of ongoing debate (Erikson Reference Erikson2015). One view is that elected representatives should not pander to the views of the largely uninformed public. Rather, good representatives ought to lead by making choices that are in the enlightened interest (however defined) of citizens. We agree with Federalist Paper 71 and game-theoretic models of pandering (Canes-Wrone, Herron, and Shotts Reference Canes-Wrone, Herron and Shotts2001) that there can be too much responsiveness. However, these models cannot justify complacency about unequal responsiveness in the democratic process that lies at the center of this volume and chapter. Many disagreements about policy between rich and poor citizens concern economic bread-and-butter issues and are based on differences in material conditions or ideals. Indeed, an established political economy literature predicts and documents rational sources of disagreement. For example, consider income redistributive policies, minimum wage increases, or stimulus spending in the wake of an economic depression. On these and similar economic issues, individuals in the United States and Europe with lower incomes are, on average, significantly more in favor of government action (Gilens Reference Gilens2009; Rueda and Stegmueller Reference Rueda and Stegmueller2019; Soroka and Wlezien Reference Soroka and Wlezien2008). Based on current textbook economics, one would be hard pressed to argue that citizens supporting these policies should somehow get less weight than citizens opposing them.

Assessing the degree of unequal responsiveness requires addressing challenging measurement and estimation issues that are discussed in more detail elsewhere (e.g., see Bartels in this volume). Our interpretation of the literature is that there is sufficient (if contested) evidence for the existence of unequal responsiveness to warrant investigation of its mechanisms.

Initial research on congressional or state-level representation in the United States was limited by small survey sample sizes, which poses the risk that estimates of unequal responsiveness are mostly due to sampling noise in the measures of (correlated) group preferences (Bhatti and Erikson Reference Bhatti, Erikson, Peter and Wlezien2011).Footnote 3 However, larger surveys, such as the Cooperative Election Study (CES, formerly the Cooperative Congressional Election Study), have reduced this problem. For instance, Bartels (Reference Bartels2016: Ch. 8) uses the 2010 and 2012 CES with more than 100,000 respondents and finds differential responsiveness in the Senate. Senators’ roll-call voting behavior is positively responsive to average constituent opinion, but this is mainly driven by responsiveness to the upper third of the income distribution. Bartels’ estimates imply that senators are five times more responsive to high-income than middle-income constituents and not at all responsive to low-income constituents. Subsequent work on the US House draws on additional CES waves and corrects for possible imbalances between the survey sample and district populations using micro-level census data (Becher and Stegmueller Reference Becher and Stegmueller2021). On average, the pattern in the House is very similar to the one found for the Senate by Bartels (Reference Bartels2016).

Field experimental research has added important insights by helping to identify in a more controlled fashion biases that tend to work against the poor and in favor of the affluent. Kalla and Broockman (Reference Kalla and Broockman2016a) find that legislators are more likely to meet donors than nondonors, which bolsters the argument that money buys access. Another study sends messages from (fictional) constituents to politicians, randomly varying name and ethnicity but keeping the same content (Butler Reference Butler2014). It reveals that politicians exhibit a significant socioeconomic bias when evaluating constituent opinion. Focusing on legislative staffers in Congress, Hertel-Fernandez, Mildenberger, and Stokes (Reference Hertel-Fernandez, Mildenberger and Stokes2019) find that staffers systematically misestimate public preferences in their district. This mismatch is partially explained by personal views and contacts with business groups. Through an experiment, the study also documents that staffers are less likely to view correspondence from ordinary citizens as being representative of constituent preferences than correspondence from businesses.

Importantly, scholars extended the study of unequal representation to assemblies in Europe, Latin America, and elsewhere (e.g., Bartels Reference Bartels2017; Elkjær and Iversen Reference Elkjær and Iversen2020; Elsässer, Hense, and Schäfer Reference Elsässer, Hense and Schäfer2017; Lupu and Warner Reference Lupu and Warner2022a; Mathisen et al. 2021; Peters and Ensink Reference Peters and Ensink2015). One approach in the comparative literature is to match data on government spending with data on public spending preferences by income groups from multiple survey waves and multiple countries. Estimating time-series cross-section models on such data, some studies find that changes in policy are positively related to changes in spending preferences of the rich but not the poor (Bartels Reference Bartels2017; Peters and Ensink Reference Peters and Ensink2015). On the other hand, Elkjær and Iversen (Reference Elkjær and Iversen2020) show that these findings can be model-dependent. In their preferred regression specification, policy appears to respond only to middle-income preferences. Lupu and Warner (Reference Lupu and Warner2022a) combine elite and mass surveys in fifty-two countries over three decades to calculate the distance between the views of citizens and legislators. They find that legislators’ views are more congruent with those of the rich.

While future research will surely refine estimates of the degree of unequal representation in a larger set of democracies, one can conclude that much of this preliminary evidence runs counter to normative theories of democracy stressing substantive political equality at the policymaking stage.

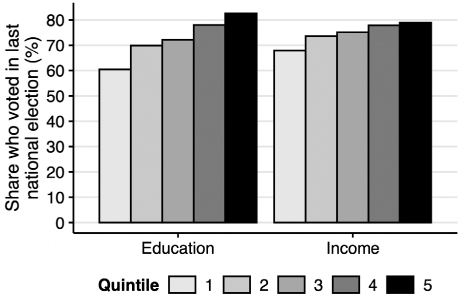

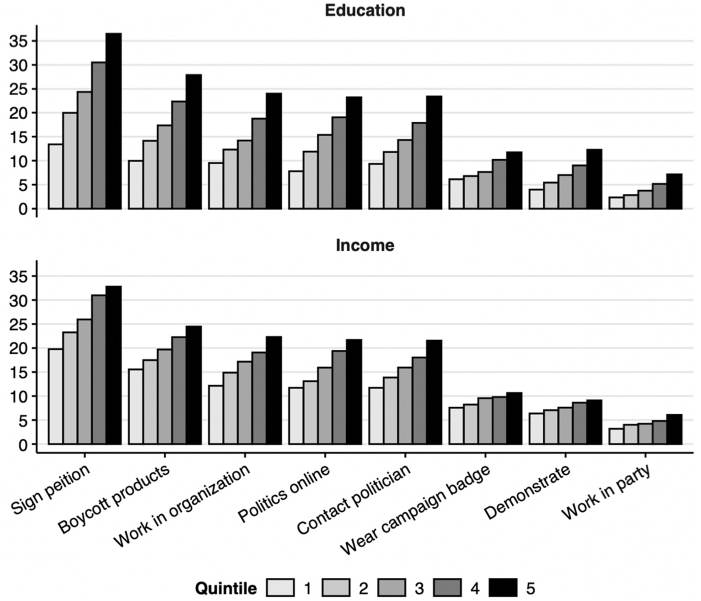

Interest Groups and the Hunt for Mechanisms

It remains an open question why there is so much political inequality in the legislative arena and what can be done about it. Surveying the literature, Bartels notes that there “is clearly a great deal more to be learned about the mechanisms by which economic inequality gets reproduced in the political realm” (2016: 267). The analysis of mechanisms in this body of scholarship has often focused on the importance of unequal political participation, knowledge, or individual campaign contributions (Bartels Reference Bartels2016; Erikson Reference Erikson2015; Gilens Reference Gilens2012).

We take a complementary perspective and ask how organized interests shape substantive political inequality. Interest groups may focus their efforts on shaping election outcomes or on swaying incumbent policymakers, whatever their partisan stripes. To what extent is unequal legislative responsiveness driven by an electoral selection channel rather than a postelectoral lobbying channel? So far, the existing evidence does not provide a clear answer about the relative importance of these two mechanisms. We will demonstrate that common empirical strategies may fail to provide a clear answer, and potentially also underestimate the overall impact of interest groups on unequal responsiveness.

One of the few studies that directly examines the relevance of organized interest for unequal responsiveness concludes that national policy in the United States is significantly biased toward economic elites and organized groups representing business interests (Gilens and Page Reference Gilens and Page2014). Related research at the subnational level finds that US states with stricter lobbying regulations exhibit less political inequality at the policymaking stage (Flavin 2015). However, these results stand in contrast with findings from a separate literature on lobbying and money in politics. It concludes that interest groups’ monetary contributions have little discernible impact on legislative voting (Ansolabehere, Figueiredo, and Snyder Reference Ansolabehere, de Figueiredo and Snyder2003) and that groups with more resources do not necessarily have much higher success rates than other groups (Baumgartner et al. Reference Baumgartner, Berry, Hojnacki, Kimball and Leech2009).

Political Selection as a Pathway to (In)equality

Partisanship

From an electoral selection perspective, unequal responsiveness in lawmaking is driven by what types of politicians are elected to office. Partisanship is often the strongest predictor of legislative voting (Bartels Reference Bartels2008; Lee, Moretti, and Butler Reference Lee, Moretti and Butler2004; McCarty, Poole, and Rosenthal Reference McCarty, Poole and Rosenthal2006), and the partisan composition of governments shapes key public policies over which people with different incomes tend to disagree (Pettersson-Lidbom Reference Pettersson-Lidbom2008). In partisan theories of political competition and public policy, different parties represent different socioeconomic groups and political competition does not lead parties to convergence to the median voter (Hibbs Reference Hibbs1987). Once in office, politicians try to implement their policy agenda and are not very sensitive to lobbying efforts to do otherwise. The account implies that reducing political inequality in a legislature requires first and foremost to balance the electoral arena.

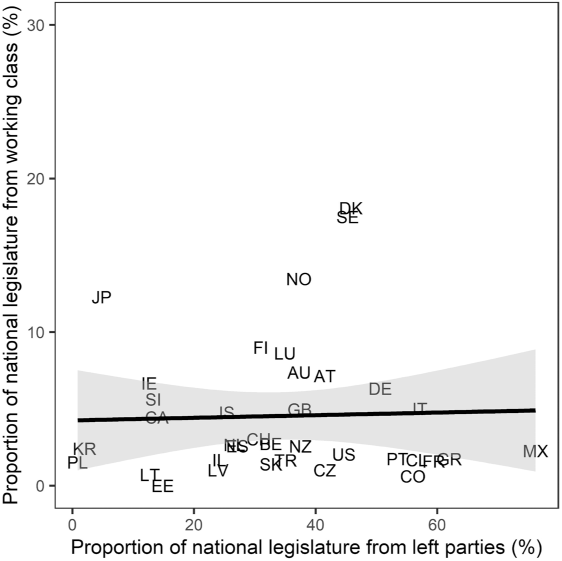

Are legislators from different parties unequally responsive to rich and poor constituents? Examining the US Congress, Bartels (Reference Bartels2016: 248–249) finds that Republican House members and senators are more responsive to high-income than to middle-income constituents and largely irresponsive to the poor. While Democratic members of Congress are generally also responsive to high-income constituents, they do respond to the views of low-income and middle-class constituents (sometimes to the extent that there is no statistical difference in rates of responsiveness). An analysis drawing on rich individual-level voter registration data confirms this basic pattern (Rhodes and Schaffner Reference Rhodes and Schaffner2017).Footnote 4 A comparative analysis of policy adoption in four European countries finds that unequal responsiveness is less pronounced when Left parties are in power in three out of the four countries (Mathisen et al., this volume).

Descriptive Representation

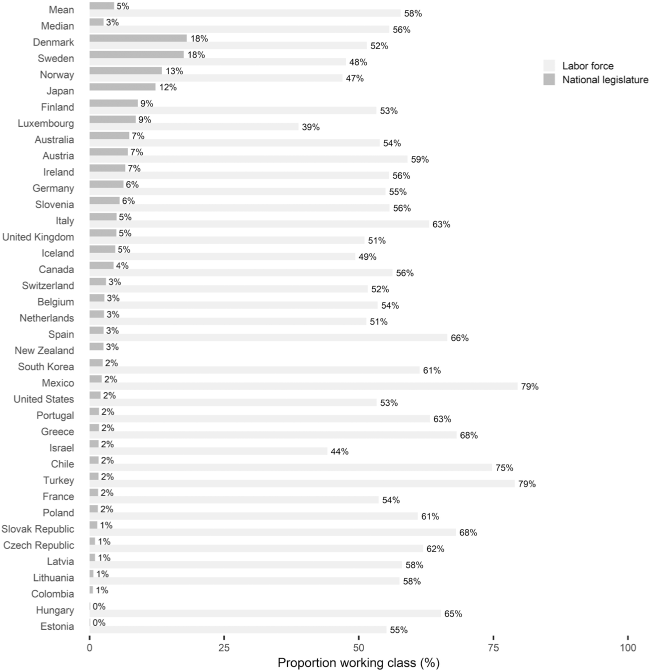

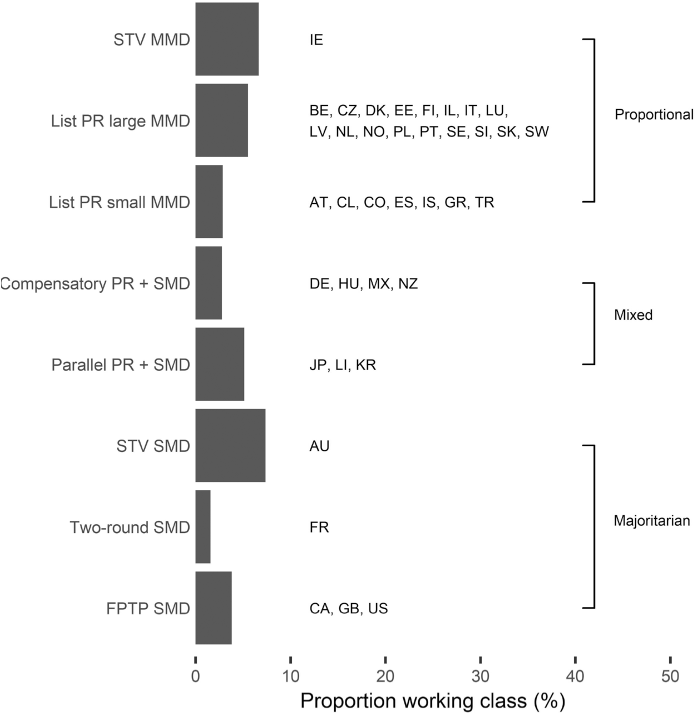

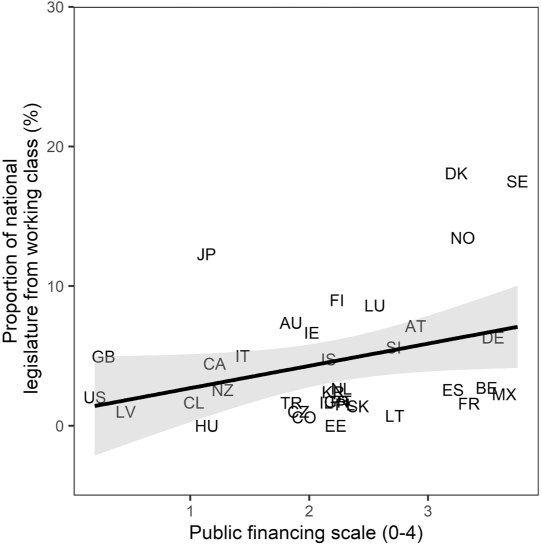

Political selection does not only concern partisanship. Individuals vary on many attributes and some of them are bound to shape how they behave in the political arena. In particular, descriptive representation matters because the composition of many legislatures is imbalanced in terms of gender and tilted toward the highly educated and well-off. Thus, one might ask, as did John Stuart Mill in his Considerations on Representative Government, if “[p]arliament, or almost any of the members composing it, ever for an instant look at any question with the eyes of a working man” (Mill Reference Mill1977 [1861])? There is ample evidence that the occupational class background of politicians matters for legislative voting in the United States (Carnes Reference Carnes2013) and, comparatively, for the positions endorsed by legislators (Carnes and Lupu Reference Carnes and Lupu2015) and the fiscal policy choices of mayors (Curto-Grau and Gallego, this volume). Politicians with a working-class background are more responsive to the views of the relatively poor, even after controlling for political party. Similarly, characteristics like gender and race shape the responsiveness of politicians (Butler Reference Butler2014; Swers Reference Swers2005).

This line of research on the link between descriptive representation and inequality in legislatures implies that barriers to entry in politics for less advantaged individuals are part of the process driving unequal political responsiveness.

What Shapes Selection?

Economic inequality may favor the selection of policymakers more inclined to consider the opinions of the affluent. For example, increased economic inequality may incentivize higher contributions by those who have most to lose from redistribution and thus change the partisan composition of the legislature (Campante Reference Campante2011).

It may be tempting to think that the electoral influence of resource-rich interest groups is predominantly an American phenomenon due to its outsize levels of campaign spending. But what matters in electoral contests is the relative financial advantage of one group over another. For example, Cagé (Reference Cagé2020) documents that in Europe, funding is not equally distributed across political parties; it tends to favor conservative over Left parties. The richest sections of society and corporations contribute the bulk of private political contributions, and their spending is not electorally neutral. For instance, while Germany has a public campaign finance system, it imposes no limits on corporate donations (with carmakers being leading contributors). In the UK, election spending is strictly regulated, but parties can receive large amounts of cash in the form of donations.Footnote 5

Electoral institutions may also matter for selection. In the absence of credible commitments by parties, one theory goes, majoritarian electoral systems experience a bias in favor of low-tax and low-redistribution parties on the Right (Iversen and Soskice Reference Iversen and Soskice2006). The bias may vary with economic inequality because Left parties will have more incentives to solve their commitment problem as inequality increases (Becher Reference Becher2016).

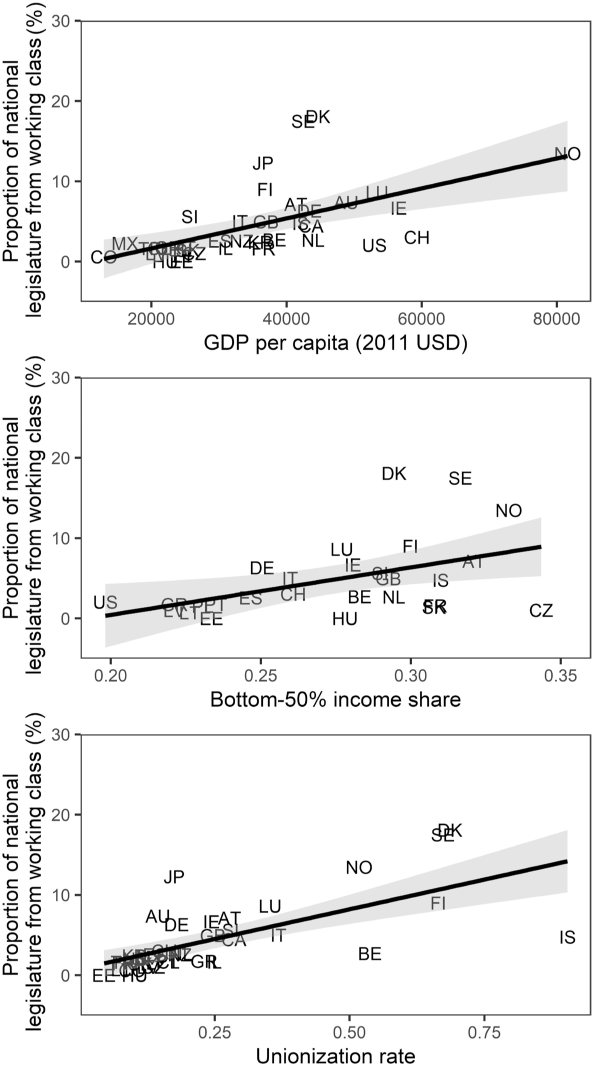

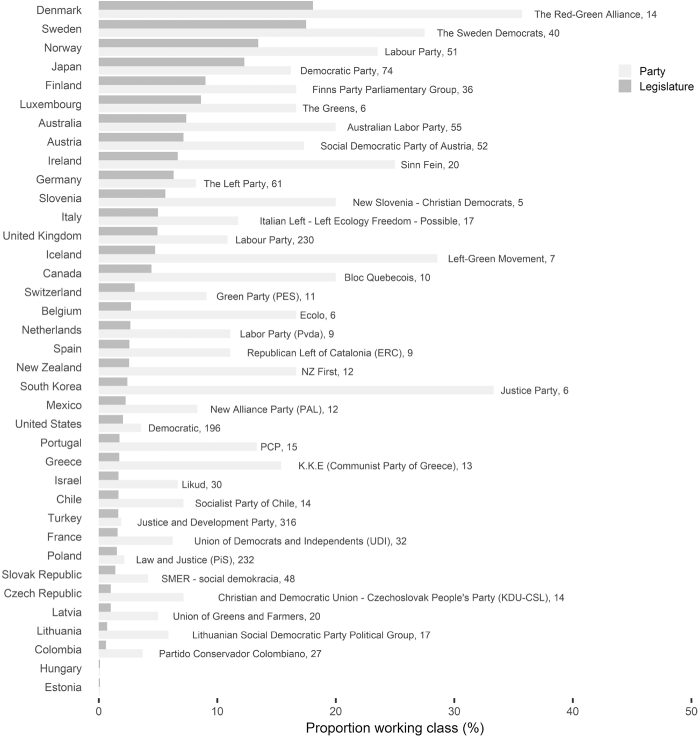

Organized labor can also be a force for more political equality. In our own previous work, we find that stronger local labor unions enhance political equality in the US House of Representatives (Becher and Stegmueller Reference Becher and Stegmueller2021), consistent with state-level evidence (Flavin Reference Flavin2018). While unions are endogenous to politics, we use an instrumental variable approach to reduce concerns about omitted confounders. In line with the evidence on partisan gaps in responsiveness just discussed above, we also find evidence that the impact of unions works at least in part through the electoral selection channel. Relatedly, Carnes and Lupu (this volume) show across countries that unionization is positively correlated with the proportion of legislators with a working-class background.

Postelectoral Influence as a Pathway to (In)equality

Other accounts of unequal democracy emphasize the importance of postelectoral politics. While campaign contributions shape elections, they and other material inducements (e.g., dinners, vacations, well-paid board appointments, revolving doors) are often thought to make the incumbent, who looks forward to the next election, more pliable to the views of well-organized groups (Grossman and Helpman Reference Grossman and Helpman2001). Economic inequality entails resource advantages for corporations and the wealthy over average citizens and mass organizations. As a result, even supposedly pro-poor politicians may join the legislative coalition in favor of the economically advantaged (Hacker and Pierson Reference Hacker and Pierson2010).

Postelectoral influence can take various forms, such as exchange or persuasion. Due to well-known measurement and causal identification issues, empirically testing the political efficacy of lobbying is difficult (Baumgartner et al. Reference Baumgartner, Berry, Hojnacki, Kimball and Leech2009; Figueiredo and Richter Reference Figueiredo and Kelleher Richter2014). The literature has paid particular attention on how to isolate the impact of organized groups’ monetary contributions on legislators’ behavior from that of legislators’ party, ideology, and constituency. To improve the veracity of regression analyses of legislative votes in this respect, the review article of Ansolabehere, Figueiredo, and Snyder (Reference Ansolabehere, de Figueiredo and Snyder2003) recommends controlling for legislators’ party affiliation or, if possible, to include legislator fixed effects that capture policymakers’ time-invariant attributes. While intuitively appealing, it is noteworthy that this approach equates interest group influence with postelectoral lobbying. This strategy can fail to estimate the relevance of the postelectoral channel if preelectoral influence and postelectoral influence are strategic complements. Below, we argue that this is likely to be the case in times of party polarization.

Field experiments support the idea that money (or even the promise thereof) provides access to legislators (Hertel-Fernandez, Mildenberger, and Stokes Reference Hertel-Fernandez, Mildenberger and Stokes2019; Kalla and Broockman Reference Kalla and Broockman2016a). Also consistent with a postelectoral influence view, observational research has found that the revenue of lobbyists connected to legislators drops substantively once their former employer leaves the legislature (Blanes i Vidal et al. Reference Blanes Vidal, Draca and Fons-Rosen2012). A study of the congressional agenda based on legislative speeches finds that corporate contributions are associated with lower attention by legislators to issue like inequality and wages and higher attention to upper-class issues (Kelly et al. Reference Kelly, Morgan, Witko and Enns2019). Labor contributions are associated with higher attention to inequality and wages and lower attention to upper-class issues. These results hold conditional on partisanship and committee assignment.

Theories differ on whether organized groups should mainly lobby opposed legislators, legislators that are on the fence on the issue, or legislators who are friendly toward their position (Austen-Smith and Wright Reference Austen-Smith and Wright1994; Grossman and Helpman Reference Grossman and Helpman2001; Hall and Deardorff Reference Hall and Deardorff2006). Following the formal model of Hall and Deardorff (Reference Hall and Deardorff2006) and an older interest group literature, we argue that organized groups will often concentrate their lobbying efforts on friendly legislators.

Why should organized groups lobby friendly legislators? One useful way to think about lobbying is as providing a matching grant or legislative subsidy that assists like-minded legislators to achieve their own objectives (Hall and Deardorff Reference Hall and Deardorff2006). For example, a conservative legislator may generally believe that the corporate tax rate should be cut, but there are numerous issues on the legislative agenda that require her attention. Given limited time and resources in a legislature that considers thousands of issues each term, providing assistance (e.g., resources and information) enables the legislator to actively support the issue: drafting bills or amendments, convincing constituents, convening with cross-pressured colleagues, and finally casting a corresponding vote. In addition, lobbying friendly legislators counteracts lobbying of opposing groups (Austen-Smith and Wright Reference Austen-Smith and Wright1994).

Selection and Postelectoral Influence as Complements

Rather than being alternative drivers of political (in)equality, electoral selection and postelectoral lobbying may go hand in hand. Organized interests maximizing their influence over the policy outcome pursue two objectives. First, ensuring that legislators already friendly to its interests are elected and, second, providing the elected friendly legislators with support to achieve their goals in the postelectoral arena. Then it will be especially difficult to unbundle the mechanisms empirically and applying standard statistical approaches to study mechanisms is likely to lead to wrong conclusions.

To clarify this argument, the section below introduces a simple formal model of a two-stage political process with an electoral and a postelectoral stage. Assuming that both channels may be complementary, the model highlights the resulting behavior of organized interests and legislators. The political equilibrium is then used as input for generating simulated legislatures. The main point of the model is to provide clear analytical foundations for the data generating process used in the simulation, and for this purpose, it prioritizes accessibility and transparency over technicality. Each of the model’s key components is based on a rich literature and more elaborate game-theoretic analysis. The strategic interaction of electoral selection and postelectoral lobbying we present here is relatively novel and has implications for empirical research on unequal responsiveness in legislatures that are not as apparent without the guiding light of the model.

A Two-Stage Model

An organized group, ![]() , cares about the policy action of an elected policymaker,

, cares about the policy action of an elected policymaker, ![]() . The policymaker may be an individual legislator or a collective legislative body. Group

. The policymaker may be an individual legislator or a collective legislative body. Group ![]() may represent the interest of the relatively poor (e.g., organized labor), or that of the relatively rich (e.g., corporate interest groups).

may represent the interest of the relatively poor (e.g., organized labor), or that of the relatively rich (e.g., corporate interest groups). ![]() faces a binary policy choice

faces a binary policy choice ![]() .

. ![]() ’s utility from policy

’s utility from policy ![]() versus policy

versus policy ![]() is given by

is given by ![]() and

and ![]() , respectively. To fix ideas, we assume throughout that

, respectively. To fix ideas, we assume throughout that ![]() , so that

, so that ![]() strictly prefers policy

strictly prefers policy ![]() to policy

to policy ![]() . The model can be interpreted in two ways without affecting the analysis. First, think of

. The model can be interpreted in two ways without affecting the analysis. First, think of ![]() as a labor union supporting a policy,

as a labor union supporting a policy, ![]() , of more social protection for individuals in the lower half of the income distribution over policy

, of more social protection for individuals in the lower half of the income distribution over policy ![]() that would remove such protections. Here, the group will balance the proclivity of the policymaker to side with economic elites and business interests documented in the literature. One possible implication is that the decline in organized labor as a countervailing power is an important driver of political inequality. Second, one can think of

that would remove such protections. Here, the group will balance the proclivity of the policymaker to side with economic elites and business interests documented in the literature. One possible implication is that the decline in organized labor as a countervailing power is an important driver of political inequality. Second, one can think of ![]() as corporate interests pushing for lower taxes on corporations or top incomes. Here,

as corporate interests pushing for lower taxes on corporations or top incomes. Here, ![]() wants legislators to support a policy that is not preferred by middle-income and low-income constituents. For concreteness, we will focus on the first interpretation in the text. But it is important to keep in mind that the model also applies to the second case.Footnote 6

wants legislators to support a policy that is not preferred by middle-income and low-income constituents. For concreteness, we will focus on the first interpretation in the text. But it is important to keep in mind that the model also applies to the second case.Footnote 6

Policy is made in a representative democracy, where ![]() can influence policy in two distinct stages of the political process: via lobbying elected representatives and by affecting what type of legislator is elected in the first place. To impact the latter in an election,

can influence policy in two distinct stages of the political process: via lobbying elected representatives and by affecting what type of legislator is elected in the first place. To impact the latter in an election, ![]() can take some costly action, such as campaign contributions, get-out-the-vote campaigns, or advertisement, to stochastically improve the chances that its preferred type of policymaker is elected. To impact the former,

can take some costly action, such as campaign contributions, get-out-the-vote campaigns, or advertisement, to stochastically improve the chances that its preferred type of policymaker is elected. To impact the former, ![]() can lobby elected representatives to increase the probability of them supporting a given policy. Policymakers differ in their policy priorities, be it due to party membership or categories such as gender, race, or class background. We assume that there are two types of legislators,

can lobby elected representatives to increase the probability of them supporting a given policy. Policymakers differ in their policy priorities, be it due to party membership or categories such as gender, race, or class background. We assume that there are two types of legislators, ![]() , where

, where ![]() indicates left and

indicates left and ![]() right, to capture the most important aspect of current partisan polarization. Then group

right, to capture the most important aspect of current partisan polarization. Then group ![]() may choose to lobby a policymaker after the election and

may choose to lobby a policymaker after the election and ![]() then chooses either policy

then chooses either policy ![]() or

or ![]() . The model developed below considers a strategic group and agent-based policymakers acting under political uncertainty.

. The model developed below considers a strategic group and agent-based policymakers acting under political uncertainty.

The Electoral Stage

During the election, ![]() chooses a level of mobilization effort, denoted by

chooses a level of mobilization effort, denoted by ![]() , that may be low (

, that may be low (![]() ) or high (

) or high (![]() ). All that we need to assume is that a higher mobilization effort translates into a higher probability that the group’s preferred type of politician wins the election. In a two-candidate race in a first-past-the-post system, this requires winning just more than 50 percent of the vote. Say

). All that we need to assume is that a higher mobilization effort translates into a higher probability that the group’s preferred type of politician wins the election. In a two-candidate race in a first-past-the-post system, this requires winning just more than 50 percent of the vote. Say ![]() ’s policy interests are more in line with Left policymakers so that

’s policy interests are more in line with Left policymakers so that ![]() prefers

prefers ![]() over

over ![]() . We model an electorate with a large number of voters (i.e., there are no ties). Denote by

. We model an electorate with a large number of voters (i.e., there are no ties). Denote by ![]() the share of votes obtained by a candidate of type

the share of votes obtained by a candidate of type ![]() . The mobilization assumption made above then translates to

. The mobilization assumption made above then translates to ![]() .

.

A group’s mobilization capacity depends on two key factors. First, the cost of mobilization, which is represented by a nonnegative scalar, ![]() . Second, the group’s exogenously determined strength, for example, its membership size or capital stock. We represent the total of the latter by nonnegative scalar

. Second, the group’s exogenously determined strength, for example, its membership size or capital stock. We represent the total of the latter by nonnegative scalar ![]() . Groups with larger mobilization capacity have a larger impact on electoral politics:

. Groups with larger mobilization capacity have a larger impact on electoral politics:

The Postelectoral Stage

As already argued above, we consider the situation where electoral mobilization (and the resulting selection of ![]() ) and postelectoral lobbying are not perfect substitutes. Managing to get a number of type

) and postelectoral lobbying are not perfect substitutes. Managing to get a number of type ![]() politicians elected is not necessarily enough for

politicians elected is not necessarily enough for ![]() to achieve its policy objectives. While

to achieve its policy objectives. While ![]() policymakers are a priori more favorable toward

policymakers are a priori more favorable toward ![]() than type

than type ![]() policymakers, their support for the policy cannot be taken for granted by

policymakers, their support for the policy cannot be taken for granted by ![]() . Policymakers vary in their ideological or partisan constraints and commitments. Think of type

. Policymakers vary in their ideological or partisan constraints and commitments. Think of type ![]() politicians as having a large policy agenda and facing offers from other groups on other dimensions, so that they have to make a decision of whether to exert costly effort (e.g., drafting a proposal) to support

politicians as having a large policy agenda and facing offers from other groups on other dimensions, so that they have to make a decision of whether to exert costly effort (e.g., drafting a proposal) to support ![]() . Thus, after the election,

. Thus, after the election, ![]() considers whether and how much to lobby any given elected policymaker. Lobbying may take varying forms such as exerting pressure or providing information and resources. We represent lobbying effort by a nonnegative real number,

considers whether and how much to lobby any given elected policymaker. Lobbying may take varying forms such as exerting pressure or providing information and resources. We represent lobbying effort by a nonnegative real number, ![]() . Note, that due to the aforementioned heterogeneity in priorities and constraints, not all politicians are equally responsive to being lobbied by

. Note, that due to the aforementioned heterogeneity in priorities and constraints, not all politicians are equally responsive to being lobbied by ![]() .

.

Rather than modeling the full complexity of postelectoral politics, we capture this logic in a reduced form by using a contest success function (Cornes and Hartley Reference Cornes and Hartley2005; Tullock Reference Tullock, James, Robert and Tullock1980). The probability that a policymaker chooses ![]() over

over ![]() is characterized by the effectiveness of group

is characterized by the effectiveness of group ![]() ’s lobbying in favor of

’s lobbying in favor of ![]() relative to countervailing influences (such as lobbying efforts of competing interest groups or the opportunity cost of not pursuing other issues), which are captured by a hurdle factor

relative to countervailing influences (such as lobbying efforts of competing interest groups or the opportunity cost of not pursuing other issues), which are captured by a hurdle factor ![]() :

:

Here ![]() is

is ![]() ’s exogenous strength and

’s exogenous strength and ![]() is the endogenous lobbying effort as defined above. The hurdle factor

is the endogenous lobbying effort as defined above. The hurdle factor ![]() is a nonnegative real number that depends on the type of politician. For a given lobbying effort, Left politicians are more willing to support

is a nonnegative real number that depends on the type of politician. For a given lobbying effort, Left politicians are more willing to support ![]() than Right politicians:

than Right politicians: ![]() . An instructive case is that only

. An instructive case is that only ![]() types are positively responsive to

types are positively responsive to ![]() ’s lobbying (i.e.,

’s lobbying (i.e., ![]() is sufficiently large to render lobbying

is sufficiently large to render lobbying ![]() types prohibitive). Should

types prohibitive). Should ![]() decide not to lobby

decide not to lobby ![]() then policy

then policy ![]() is the certain outcome. Lobbying is costly and, following much of the literature using contest functions, we assume a linear cost structure.

is the certain outcome. Lobbying is costly and, following much of the literature using contest functions, we assume a linear cost structure.

Analysis

Given the sequential nature of the interaction, the analysis starts in the postelectoral stage. For a given type of the policymaker, ![]() chooses lobbying effort

chooses lobbying effort ![]() to maximize the payoff:

to maximize the payoff:

The first order condition implies that ![]() chooses

chooses ![]() until marginal expected benefits of lobbying equal marginal cost:

until marginal expected benefits of lobbying equal marginal cost:

For nonnegative values of ![]() , group

, group ![]() ’s optimal behavior is well defined and has a unique best response (Cornes and Hartley Reference Cornes and Hartley2005). Solving the equation above yields the optimal lobbying effort:

’s optimal behavior is well defined and has a unique best response (Cornes and Hartley Reference Cornes and Hartley2005). Solving the equation above yields the optimal lobbying effort:

Two intuitive results emerge. First, higher policy stakes for the interest group, captured by a larger utility differential for policies ![]() and

and ![]() ,

, ![]() , induce more lobbying effort. Second, the effect of the hurdle factor

, induce more lobbying effort. Second, the effect of the hurdle factor ![]() on postelectoral lobbying is nonmonotonic. As opposing forces make a legislator less inclined to support the policy preferred by

on postelectoral lobbying is nonmonotonic. As opposing forces make a legislator less inclined to support the policy preferred by ![]() for a given amount of lobbying, increasing

for a given amount of lobbying, increasing ![]() ’s lobbying effort pays off when the initial hurdle is relatively low (

’s lobbying effort pays off when the initial hurdle is relatively low (![]() ) but not when the hurdle is already high (

) but not when the hurdle is already high (![]() ).

).

Given the optimal postelectoral lobbying behavior, we now show ![]() ’s choice of costly mobilization effort. To simplify notation, consider the probabilities of the key outcomes. Denote by

’s choice of costly mobilization effort. To simplify notation, consider the probabilities of the key outcomes. Denote by ![]() the probability of seeing a Left legislator elected given high mobilization effort,

the probability of seeing a Left legislator elected given high mobilization effort, ![]() , and by

, and by ![]() given low mobilization effort,

given low mobilization effort, ![]() . Denote by

. Denote by ![]() the probability of obtaining the preferred policy given optimal lobbying of a type

the probability of obtaining the preferred policy given optimal lobbying of a type ![]() legislator,

legislator, ![]() , and by

, and by ![]() the respective probability for a legislator of type

the respective probability for a legislator of type ![]() .

.

Group ![]() exerts costly mobilization effort at the electoral stage if and only if the expected value of mobilizing is larger than the cost:

exerts costly mobilization effort at the electoral stage if and only if the expected value of mobilizing is larger than the cost:

Mobilization thus requires that the group is sufficiently strong (i.e., ![]() is sufficiently large), that the policy stakes

is sufficiently large), that the policy stakes ![]() ) are sufficiently high relative to the cost of mobilization (

) are sufficiently high relative to the cost of mobilization (![]() ), and that there is party polarization captured by the partisan gap in responsiveness to postelectoral lobbying effect (

), and that there is party polarization captured by the partisan gap in responsiveness to postelectoral lobbying effect (![]() ).

).

Party polarization is low when legislators of either party have a similar probability of supporting policy ![]() for a given amount of postelectoral lobbying. If party polarization is sufficiently low, then even a strong group will focus all its efforts on postelectoral lobbying. In the context of sufficiently high party polarization, the interest group will first engage in electoral mobilization on behalf of its preferred candidate, and then engage in postelectoral lobbying if its preferred candidate wins the election. This logic implies that interest group strategies systematically vary across context.

for a given amount of postelectoral lobbying. If party polarization is sufficiently low, then even a strong group will focus all its efforts on postelectoral lobbying. In the context of sufficiently high party polarization, the interest group will first engage in electoral mobilization on behalf of its preferred candidate, and then engage in postelectoral lobbying if its preferred candidate wins the election. This logic implies that interest group strategies systematically vary across context.

Consider the interaction of both stages in the case of high polarization such that only type ![]() politicians are responsive to

politicians are responsive to ![]() ’s lobbying (i.e.,

’s lobbying (i.e., ![]() is sufficiently large such that

is sufficiently large such that ![]() for feasible values of

for feasible values of ![]() ). Then, a strong

). Then, a strong ![]() will exert mobilization effort and, if

will exert mobilization effort and, if ![]() wins the election, postelectoral lobbying effort to achieve its preferred policy,

wins the election, postelectoral lobbying effort to achieve its preferred policy, ![]() . On the one hand, mobilization alone is not sufficient to affect the policy outcome. On the other hand, a rational group will not solely rely on lobbying. Everything else equal, the strength of

. On the one hand, mobilization alone is not sufficient to affect the policy outcome. On the other hand, a rational group will not solely rely on lobbying. Everything else equal, the strength of ![]() , as parameterized by

, as parameterized by ![]() , improves both the electoral and the postelectoral chain of influence:

, improves both the electoral and the postelectoral chain of influence: ![]() is more likely to prevail in the election and more likely to choose policy

is more likely to prevail in the election and more likely to choose policy ![]() . In equilibrium, the selection of the preferred type of politician and the use postelectoral lobbying are strongly correlated.

. In equilibrium, the selection of the preferred type of politician and the use postelectoral lobbying are strongly correlated.

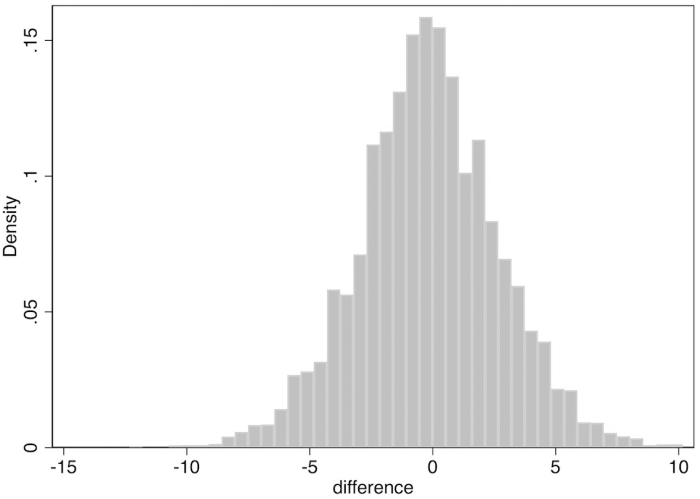

Evidence from Simulated Legislatures

We trace the implications of our model for empirical analysis using a simulation approach. We create 5,000 simulated legislatures, each with 435 legislators, whose composition is the result of an electoral process including strategic mobilization and whose policy choice is the result of strategic postelectoral lobbying. Each legislator faces the choice of supporting one of two policies, ![]() or

or ![]() , in a roll-call vote (or prior action such as cosponsorship).

, in a roll-call vote (or prior action such as cosponsorship).

The simulation captures a situation where policy ![]() is preferred over policy

is preferred over policy ![]() by citizens in the middle and lower part of the income distribution, but economic elites and business interest groups generally have opposing preferences. In this environment, mass-based organizations like labor unions may be a force for more political inequality in legislatures (Becher and Stegmueller Reference Becher and Stegmueller2021; Flavin Reference Flavin2018). Continuing with this running example, we would like to know to what extent the effect of organized labor on legislative responsiveness works through political selection rather than postelectoral bargaining. Nothing changes with respect to the identification challenges for unbundling the mechanisms if one prefers to interpret unions as enhancing inequality or if one thinks of the organized group

by citizens in the middle and lower part of the income distribution, but economic elites and business interest groups generally have opposing preferences. In this environment, mass-based organizations like labor unions may be a force for more political inequality in legislatures (Becher and Stegmueller Reference Becher and Stegmueller2021; Flavin Reference Flavin2018). Continuing with this running example, we would like to know to what extent the effect of organized labor on legislative responsiveness works through political selection rather than postelectoral bargaining. Nothing changes with respect to the identification challenges for unbundling the mechanisms if one prefers to interpret unions as enhancing inequality or if one thinks of the organized group ![]() as a business group that has preferences add odds with the majority of voters (Gilens Reference Gilens2012; Gilens and Page Reference Gilens and Page2014; Grossman and Helpman Reference Grossman and Helpman2001).

as a business group that has preferences add odds with the majority of voters (Gilens Reference Gilens2012; Gilens and Page Reference Gilens and Page2014; Grossman and Helpman Reference Grossman and Helpman2001).

Table 6.1 shows the parameter values used in our simulation. To generate variation in the ability of the group to affect legislative behavior and thus substantive political equality, the group strength parameter across the 435 districts is drawn from a uniform distribution ranging from 0.05 to 0.21. This represents district-level variation in union strength (e.g., number of union members). We base this range on district-level membership estimates found in the data of Becher, Stegmueller, and Kaeppner (Reference Becher, Stegmueller and Kaeppner2018).

Table 6.1 Parameter values

| Parameter | Label | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Group strength | U (0.05, 0.21) | |

| Policy polarization | 5 | |

| Lobbying hurdle | 0.06 | |

| Mobilization costs | 0.15 | |

| Left vote share under | U (0.30, 0.61) | |

| Number of legislators | 435 |

In the absence of any mobilization effort by the group, the vote share of Left legislators can vary from 0.3 to 0.61; the expected value of Left vote share is ![]() .Footnote 7 Thus, Left candidates are electorally disadvantaged compared to their Right competitors but with a narrow enough margin to make electoral mobilization worthwhile in expectation for a well-organized group.Footnote 8 Realistically, there is significant political polarization, as represented by the utility difference between policy

.Footnote 7 Thus, Left candidates are electorally disadvantaged compared to their Right competitors but with a narrow enough margin to make electoral mobilization worthwhile in expectation for a well-organized group.Footnote 8 Realistically, there is significant political polarization, as represented by the utility difference between policy ![]() and policy

and policy ![]() . Organized interests face a complementarity between partisan selection and lobbying. The positive lobbying hurdle for Left politicians (

. Organized interests face a complementarity between partisan selection and lobbying. The positive lobbying hurdle for Left politicians (![]() ) implies that without being lobbied by

) implies that without being lobbied by ![]() , even like-minded legislators would not support policy

, even like-minded legislators would not support policy ![]() ; right politicians are never willing to support

; right politicians are never willing to support ![]() for feasible lobbying efforts by

for feasible lobbying efforts by ![]() .Footnote 9 This setup produces partisan voting patterns that are in line with many key votes.Footnote 10

.Footnote 9 This setup produces partisan voting patterns that are in line with many key votes.Footnote 10

Common Statistical Specifications

We now turn to analyses of the simulated legislatures using standard regression approaches used in the literature on legislative voting and representation. A key parameter of interest is the regression coefficient for ![]() , which captures the average effect of

, which captures the average effect of ![]() ’s strength in a legislator’s district on representational inequality. A common specification would regress a legislator’s support for policy

’s strength in a legislator’s district on representational inequality. A common specification would regress a legislator’s support for policy ![]() (i.e., a recorded roll-call vote) on the group strength variable and a set of district characteristics. We have constructed the data-generating process such that there is no endogeneity problem with respect to group strength and legislative behavior.Footnote 11 This is to focus on the mechanism problem. It illustrates the difficulties that can arise even when researchers have an exogenous measure of the group’s power in each district.Footnote 12 A key decision when deciding on a model specification is the choice of how to treat the partisan identity (or descriptive characteristics) of the legislator, captured by an indicator variable equal to 1 if

(i.e., a recorded roll-call vote) on the group strength variable and a set of district characteristics. We have constructed the data-generating process such that there is no endogeneity problem with respect to group strength and legislative behavior.Footnote 11 This is to focus on the mechanism problem. It illustrates the difficulties that can arise even when researchers have an exogenous measure of the group’s power in each district.Footnote 12 A key decision when deciding on a model specification is the choice of how to treat the partisan identity (or descriptive characteristics) of the legislator, captured by an indicator variable equal to 1 if ![]() . We begin with a specification that does not include this indicator, followed by a specification where it is included. The reasons for its inclusion are usually given in terms of either “controlling for partisanship” or in an informal attempt to capture the selection channel and distinguish it from a residual “direct” channel.Footnote 13 Partisanship has a key practical advantage for researchers. It is directly observable and measured with little error. This contrasts with a group’s lobbying effort, which can use multiple instruments and only some of them are observable to researchers (Figueiredo and Richter Reference Figueiredo and Kelleher Richter2014).

. We begin with a specification that does not include this indicator, followed by a specification where it is included. The reasons for its inclusion are usually given in terms of either “controlling for partisanship” or in an informal attempt to capture the selection channel and distinguish it from a residual “direct” channel.Footnote 13 Partisanship has a key practical advantage for researchers. It is directly observable and measured with little error. This contrasts with a group’s lobbying effort, which can use multiple instruments and only some of them are observable to researchers (Figueiredo and Richter Reference Figueiredo and Kelleher Richter2014).

Table 6.2 shows the resulting estimates obtained from linear probability models (accompanied by the required heteroscedasticity-consistent standard errors). Column (1) shows that group strength significantly increases the support for policy ![]() . A marginal increase in group strength increases the probability of a legislator supporting the policy by

. A marginal increase in group strength increases the probability of a legislator supporting the policy by ![]() percentage points. Expressed in substantive terms, a one standard deviation increase in group strength increases the probability by about 7 percentage points. This represents the “total impact” of an increase in group strength on policy adoption both via changing the likelihood of the election of Left legislators and via changing their support for the policy via lobbying once elected. A researcher including the partisan identity of legislators in the specification would obtain the results displayed in column (2). The estimate for the partisanship variable is large and clearly statistically different from zero (

percentage points. Expressed in substantive terms, a one standard deviation increase in group strength increases the probability by about 7 percentage points. This represents the “total impact” of an increase in group strength on policy adoption both via changing the likelihood of the election of Left legislators and via changing their support for the policy via lobbying once elected. A researcher including the partisan identity of legislators in the specification would obtain the results displayed in column (2). The estimate for the partisanship variable is large and clearly statistically different from zero (![]() ). The coefficient for group strength is drastically reduced and almost five times smaller compared to specification (1). Given the size of its standard error, one would have to conclude that it is statistically indistinguishable from zero. Faced with these empirical results, a researcher might reach the conclusion that only partisan selection matters for the support of policy

). The coefficient for group strength is drastically reduced and almost five times smaller compared to specification (1). Given the size of its standard error, one would have to conclude that it is statistically indistinguishable from zero. Faced with these empirical results, a researcher might reach the conclusion that only partisan selection matters for the support of policy ![]() – which is clearly incorrect given the model that generated the data, in which the selection channel alone is not sufficient to change substantive representation in the legislature. Recall that without any lobbying of friendly legislators (something that does not occur in equilibrium), all legislators would support policy

– which is clearly incorrect given the model that generated the data, in which the selection channel alone is not sufficient to change substantive representation in the legislature. Recall that without any lobbying of friendly legislators (something that does not occur in equilibrium), all legislators would support policy ![]() .

.

Table 6.2 Group strength, electoral selection, lobbying, and legislative responsiveness

| (1) | (2) | (3) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Est. | s.e. | Est. | s.e. | Est. | s.e. | |

| Group strength | 1.559 | (0.484) | 0.327 | (0.307) | 0.005 | (0.143) |

| Left legislator | 0.753 | (0.031) | 0.919 | (0.159) | ||

| Postelection effortFootnote a | −0.108 | (0.106) | ||||

Notes: Based on ![]() simulated legislatures with 435 members. Intercepts not shown. Estimates from linear probability model with heteroscedasticity-consistent standard errors.

simulated legislatures with 435 members. Intercepts not shown. Estimates from linear probability model with heteroscedasticity-consistent standard errors.

a Postelection effort observed without measurement error (or measured via proxy with known and adjusted reliability). Correlation of postelection effort with electoral mobilization, ![]() 0.023; correlation with left election winner,

0.023; correlation with left election winner, ![]() 0.962.

0.962.

Just Omitted Variable Bias?

Are these stark results simply the result of omitted variable bias, namely omitted postelection lobbying effort? Specification (3) of Table 6.2 includes a measure of the intensity of lobbying after the election. More precisely, we include the level of optimal postelection effort (parameter ![]() in our model). Usually, researchers will not have access to this variable, but work with an imperfect proxy or one or several of its components, which raises issues of errors-in-variables bias. Here, we show a best-case scenario, where a researcher either fully observes

in our model). Usually, researchers will not have access to this variable, but work with an imperfect proxy or one or several of its components, which raises issues of errors-in-variables bias. Here, we show a best-case scenario, where a researcher either fully observes ![]() or corrects for known reliability of the variable measured with error. As the estimate for

or corrects for known reliability of the variable measured with error. As the estimate for ![]() signifies, the inclusion of lobbying effort does not recover the impact of group strength when the true data-generating process exhibits strategic complementarities.

signifies, the inclusion of lobbying effort does not recover the impact of group strength when the true data-generating process exhibits strategic complementarities.

Can Mediation Analysis Recover the True Effect?

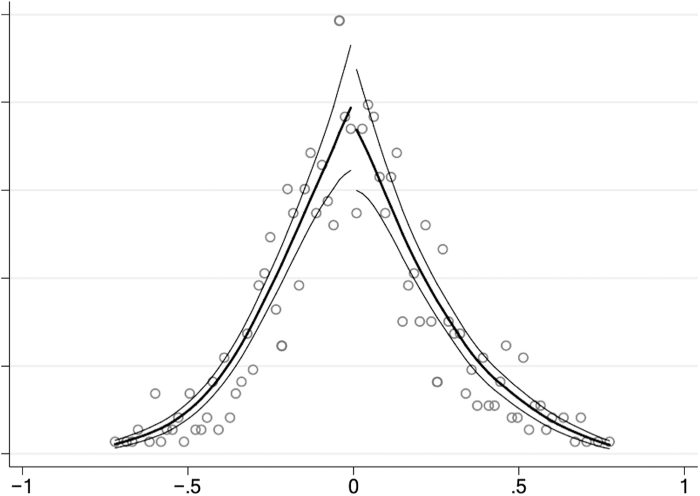

Given advances in the statistical analysis of causal mechanisms, researchers explicitly interested in mechanisms may go beyond the regression analysis above and opt for an explicit effect decomposition. The goal of this approach is to decompose the effect of group strength on policy choice into an indirect component channeled via partisanship and a direct or remaining component (e.g., Pearl Reference Pearl2001). Imai et al. (Reference Imai, Keele, Tingley and Yamamoto2011) define the former as an average causally mediated effect (ACME) and the latter as an average direct effect (ADE). We follow their definition and their guidance about best empirical practice (Imai, Keele, and Yamamoto Reference Imai, Keele and Yamamoto2010).

Panel (A) of Table 6.3 shows the resulting causal effect decomposition estimates.Footnote 14 The ACME is ![]() indicating a substantively and statistically significant impact of group strength via the selection of a Left legislator. In contrast, the ADE of group strength is only

indicating a substantively and statistically significant impact of group strength via the selection of a Left legislator. In contrast, the ADE of group strength is only ![]() and not statistically distinguishable from zero. Almost 80 percent of the total effect of group strength is mediated by the selection of a Left legislator. Again, these findings would tempt a researcher into drawing a conclusion contrary to the true model generating the data. Namely, they might conclude that it is the partisanship of the legislator, and thus the selection mechanism, that matters most for the support of a policy in the legislature and that, as indicated by the remaining effect of group strength, postelectoral influence plays a comparatively small (even “insignificant”) role.

and not statistically distinguishable from zero. Almost 80 percent of the total effect of group strength is mediated by the selection of a Left legislator. Again, these findings would tempt a researcher into drawing a conclusion contrary to the true model generating the data. Namely, they might conclude that it is the partisanship of the legislator, and thus the selection mechanism, that matters most for the support of a policy in the legislature and that, as indicated by the remaining effect of group strength, postelectoral influence plays a comparatively small (even “insignificant”) role.

Table 6.3 Mediation analysis

| Estimate | s.e. | |

|---|---|---|

| A: Causal decomposition estimates | ||

| ACME of group strength [ | 1.232 | (0.387) |

| ADE (remaining effect of | 0.327 | (0.307) |

| Proportion of total effect of | 0.783 | |

| B: Omitted M-Y confounder | ||

| Sensitivity analysis: | 0.813 | |

| True value of | 0.962 | |

| Test | 0.000 | |

Notes: Based on ![]() simulated legislatures with 435 members. Causal decomposition estimated following Tingley et al. (Reference Tingley, Teppei Yamamoto, Keele and Imai2014) with standard errors based on 500 bootstrap draws.

simulated legislatures with 435 members. Causal decomposition estimated following Tingley et al. (Reference Tingley, Teppei Yamamoto, Keele and Imai2014) with standard errors based on 500 bootstrap draws.

A careful decomposition analysis will always include a sensitivity analysis for omitted confounding variables. A researcher realizing that unobserved variables (including postelectoral effort) are likely confounding the mediator-outcome relationship would conduct a sensitivity analysis by simulating various degrees of residual correlation, ![]() , between the mediator and outcome equation (Imai, Keele, and Yamamoto Reference Imai, Keele and Yamamoto2010). In Panel (B) of Table 6.3, we report a common quantity that emerges from this exercise: the value of

, between the mediator and outcome equation (Imai, Keele, and Yamamoto Reference Imai, Keele and Yamamoto2010). In Panel (B) of Table 6.3, we report a common quantity that emerges from this exercise: the value of ![]() where the estimated ACME becomes zero. In our simulated data, this occurs when

where the estimated ACME becomes zero. In our simulated data, this occurs when ![]() is about 0.8. Because of the large size of this correlation, a researcher might well conclude that only an unrealistically large correlation induced by omitted confounders would negate the strong estimated role of the partisan selection channel. But again, under a true data-generating process with strategic complementarity, this empirical result provides a false sense of security: the true

is about 0.8. Because of the large size of this correlation, a researcher might well conclude that only an unrealistically large correlation induced by omitted confounders would negate the strong estimated role of the partisan selection channel. But again, under a true data-generating process with strategic complementarity, this empirical result provides a false sense of security: the true ![]() value is larger than 0.8 – on average the correlation between an elected Left legislator and postelectoral lobbying effort is

value is larger than 0.8 – on average the correlation between an elected Left legislator and postelectoral lobbying effort is ![]() .

.

Roll Call Voting in the US Congress

A reader might wonder if the issues discussed in this paper do indeed show up in common empirical applications. While we attempted to choose realistic parameter values in our simulations, it is possible that empirical research might not encounter similarly stark patterns. In Table 6.4, we summarize typical analyses of four key votes in the 110th and 111th Congress. We chose votes on issues that enjoyed broad support among low-income constituents, such as the Fair Minimum Wage Act of 2007 or the Foreclosure Prevention Act of 2008. The first specification regresses roll-call votes on union strength (measured as district-level union membership calculated from administrative data in Becher, Stegmueller, and Kaeppner Reference Becher, Stegmueller and Kaeppner2018) to capture the impact of group strength on the behavior of elected representatives. Union strength does indeed have a positive impact on representation: the coefficient of (logged) union membership is of sizable magnitude and statistically significant for all four key votes.

Table 6.4 Estimates of group strength on roll-call votes for some key bills with high support among low-income constituents

| Roll-call vote | Low inc. supportFootnote a | Democratic legisl. votesFootnote b | Group strength estimates | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Union sizeFootnote c | Union size + DemocratFootnote d | ||||

| Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act | 0.62 | 223 | (96%) | 0.140 (0.030) | −0.000 (0.006) |

| Fair Minimum Wage Act | 0.82 | 233 | (100%) | 0.097 (0.025) | 0.011 (0.012) |

| Foreclosure Prevention Act | 0.70 | 227 | (96%) | 0.109 (0.028) | −0.001 (0.020) |

| Affordable Care Act | 0.64 | 219 | (87%) | 0.156 (0.033) | 0.046 (0.018) |

Note: Linear probability models with state fixed effects. Robust standard errors clustered at the state level.

a Average share of low-income citizens in 435 districts supporting the policy. Constituency preferences derived from Cooperative Election Study questions corresponding to roll-call vote. District-level small area estimation via matching to the Census population using random forests. See Becher and Stegmueller (Reference Becher and Stegmueller2021).

b Number of yea votes among Democrats. Percentage of Democratic caucus voting yea in parentheses.

c Coefficient of logged district union membership numbers. District-level union membership calculated from administrative data in Becher, Stegmueller, and Kaeppner (Reference Becher, Stegmueller and Kaeppner2018).

d Coefficient of logged district union membership numbers after adding an indicator variable for partisanship of legislator.

The final column of Table 6.4 presents a specification likely to be explored by many researchers at some point (or to be demanded by reviewers): an analysis of roll-call votes and union strength while “controlling” for a legislator’s party. We have shown above that this strategy yields misleading inferences for the impact of group strength when postelectoral influence and selection are strategic complements. This is likely the case in our empirical example given high levels of party polarization in the US Congress, where the addition of legislator partisanship drastically changes the group strength coefficient. For many key votes, the impact of logged union membership is essentially nil with coefficients statistically indistinguishable from zero. Interpreting these results as evidence for the overwhelming importance of partisan selection or of the irrelevance of unions would be misleading.

Using arguably exogenous variation in union strength based on historical mining locations, Becher and Stegmueller (Reference Becher and Stegmueller2021) find, in line with theoretical intuition, that stronger unions make it more likely that Democratic candidates win congressional elections. However, it is possible that postelectoral lobbying remains a relevant mechanism at play. Theory and evidence suggest that electoral selection and lobbying may go hand in hand when parties exhibit divergent ideologies.

Using individual-level data linking contributions and lobbying by firms, Kim, Stuckatz, and Wolters (Reference Kim, Stuckatz and Wolters2020) find that a campaign donation to a member of Congress by a firm increases the probability that the same legislator is also lobbied by 8–10 percentage points, on average. Our theoretical model highlights that even a fairly small correlation between electoral and postelectoral effort can lead to a very high correlation between electoral selection – having a friendly legislator win the election – and lobbying.

Conclusion

Interest group influence is sometimes perceived as the main source behind unequal representation in legislatures around the world. For example, the power of corporations to shape policies that diverge from the interests of much of the population is a frequent topic of news stories. Relatedly, the weakening of organized labor may have critically reduced the political voice of non-elite workers. However, academic scholarship on the issue is far from settled. Trying to understand why there appears to be so much substantive political inequality in the policymaking process, the rapidly growing unequal democracies literature has paid only limited attention to the role of organized interests. This is in part due to data constraints but may also reflect lack of theoretical attention. For European observers, it is tempting to think that interest groups and the money they bring to politics are mainly a problem for democracy in America and less institutional presidential systems in other parts of the world. While comforting, this is a deceiving thought. Recent research has revealed remarkable inequalities in campaign finance systems in European countries and positive theory highlights the potential power of special interest groups in proportional electoral systems commonly found in continental Europe.

We have highlighted through a simple model and model-based simulation the value of analyzing interest groups’ incentives on how to use their resources in the electoral and postelectoral lobbying stage. Our analysis shows that when party polarization is low, interest groups have incentives to focus on lobbying incumbent politicians, regardless of their partisan affiliation. When parties are polarized, efforts to shape the selection of partisan policymakers in elections and postelectoral lobbying go hand in hand in political equilibrium. Thus, electoral selection becomes more important as party polarization increases. This testable implication from our model may help to explain variation in interest group strategies across countries. Furthermore, ignoring this relationship may lead scholars to underestimate the importance of interest groups for political inequality.