Introduction

This chapter will review the societal and political context in which there was an evolution of approaches to address the mental health needs of children and young people.1 In the 1960s and 1970s, stimulated by socio-cultural changes, new innovations in therapeutic approaches were introduced, including family therapy and cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT). The first major longitudinal and epidemiological research studies were carried out. In the 1970s and 1980s, there were challenges to the state’s capacity to deal with a variety of social problems and various forms of child maltreatment were identified. A national multidisciplinary assessment and management framework was introduced aimed at protecting the child, supporting families and developing appropriate treatment initiatives. In the 1990s and 2000s, further interventions were developed to reverse the impact of social exclusion – for example, Sure Start. There was a consolidation of practice, including both general and highly specialised services, and further development in research and training.

The Societal Context: 1960s and 1970s

During the post-war years, the promotion of national growth and well-being had been a priority with the establishment of the National Health Service (NHS) and the welfare state.2 Then, as a result of post-war fertility and the baby boom, demographics tilted towards youth; by the 1960s and 1970s, fuelled by the ‘youth culture’, there was a marked change towards an anti-establishment cultural phenomenon in the Western world. Disaffected young people rebelled against the Vietnam War. Socially progressive values grew, encompassing feminism, women in leadership roles, environmentalism, civil rights, a sexual revolution relaxing social taboos, easier birth control, repeal of sexist laws and gay liberation. There were also increasing stresses, family break-ups, divorce and single parenthood.

Traditions: Child and Adolescent Psychiatry in the 1960s and 1970s

The Child Guidance Movement

The child guidance clinic model was established in the 1930s: the ‘trinity’ of a psychiatrist seeing the referred child, a social worker engaging with the mother and an educational psychologist testing the child and liaising with the school.3 Many child and adolescent psychiatrists underwent psychoanalytic training. Psychiatric social workers trained in casework skills and educational psychologists had a background in teaching.

Regular sessions were offered to the child or young person, promoting an attachment through a child-centred approach, using play and artistic materials to encourage the expression of feelings. The approach gave the child the experience of an adult creating a warm, positive attachment and facilitated reflecting on their lives, sharing traumatic and stressful events and trying to make sense of their anxieties and depressed mood as well as managing behaviours, solving problems and finding solutions. Casework with mothers to support them in the challenging task of parenting provided an opportunity for mothers to reflect on their own experiences, current and historical stresses, and relationships, which were influencing their parenting. They were helped in managing their children’s challenging behaviour as well as being emotionally responsive and understanding. The psychologist supported the child or young person in the educational context. By 1970, there were 367 clinics in the UK.

Child Psychotherapy

There was significant controversy in working therapeutically with children and young people.4 Anna Freud’s approach at the Hampstead Clinic emphasised the supportive ‘ego-strengthening’ role of the therapist and the use of play materials, games and activities to promote growth and resilience. Kleinian approaches at the Tavistock Clinic centred on the object-relations, transference and counter-transference interpretation of children’s play and responses to the therapist in order to resolve early sources of anxiety and promote maturation.

Winnicott, a paediatrician and psychoanalyst who gained renown from his wartime broadcasts, supported an independent/‘middle’ group approach – illustrated through his demonstrations of ‘squiggle’ drawing encounters with children. The child and the therapist challenged each other to turn a shape into an image, thus reflecting experiences which could be built on as part of a creative encounter. Winnicott built on the notion of transitional space underpinning play and creativity (see also Chapter 15).5

The Association of Child Psychotherapists, established in 1949, fostered different approaches and maintained a continuity of traditions of training in working intensively with children, adolescents and young people. Work developed with special populations of children – in residential and care contexts and with autistic spectrum disorders and learning/intellectual disability. Related creative forms of therapeutic work have developed – play therapy, art and music therapy and educational therapies.

Innovations: 1960s and 1970s

Developments of Family Therapy and Multidisciplinary Practice

Although effective, the child guidance clinic model proved static and unresponsive to the changing societal dynamics. A striking development was the growth of family therapy.6 Bowlby introduced family meetings to reinforce individual therapy; Skynner, a group analyst, worked with the family as a group. A seminal paper by Bateson, ‘The Double-Bind Theory of Schizophrenia’, in 1962, asserted that disordered communication led to pathological outcomes. Children’s mental health difficulties were triggered and maintained by pathological family interactions. Minuchin developed ‘structural’ approaches, working with family communications, boundaries and alliances aiming to alter interactions between family members and improve the functioning of the child. The model was transmitted widely by videos of therapeutic work, large-scale dramatic demonstrations and public media forums, an approach which contrasted vividly with traditional more private and reflective approaches.

Therapists were trained in experiential approaches such as ‘moving family sculptures’ and ‘role play’ to facilitate the development of skills and understanding. Live supervision of clinical work took place through one-way screens and electronic bugs in the ear. Despite reservations, there was an enthusiastic take-up of the approach. Child and adolescent psychiatrists, psychologists and social workers started working with families and collaborated to establish training, which led to the founding of the Association of Family Therapy in 1976, rebalancing the dynamics between the different professionals. Therapeutic skills could be developed and effective therapy delivered to children and their families by a range of professionals across health and social care as well as education.

Developments in Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT)

CBT emerged as an amalgam of behavioural and cognitive theories of human behaviour.7 Behavioural therapy had been developed in the 1960s and included Patterson’s parent-training model, introducing consistent approaches to managing challenging disruptive behaviour. An increased awareness of the role of cognition led to the transition to CBT in the 1970s. Internal thought processes (e.g. self-talk) began to be viewed as both targets and mechanisms of change, with an emphasis on improving cognitive skills linked with modifying behaviour. Self-instruction emerged to teach impulsive children how to control their behaviour.

Psychological disorders were attributed to maladaptive cognitive processes, with psychological vulnerabilities developing as a result of early socialisation experiences within the family. Specific CBT approaches for children and young people incorporated parent training and the development of children’s mastery over their own environment. Specific protocols emerged for the treatment of anxiety and depression, trauma-focused CBT and parent training. The Triple P and Incredible Years programmes have been widely adopted. CBT has become a well-established, online, self-guided approach, which is as effective as face-to-face treatments in appropriate circumstances.

Developments in Research and Practice in Child and Adolescent Mental Health

Attachment

Bowlby’s 1951 review of maternal deprivation in Maternal Care and Mental Health had a significant influence on the development of research in the field.8 He highlighted the core role of maternal attachment for the secure development of the child. Psychoanalytic colleagues criticised his emphasising the role of real-life experiences rather than the inner world. Rutter praised positive consequences, for example parents staying with their children in hospital but echoed feminist criticisms that even brief daily maternal separations were assumed to be harmful.9 He observed that the controversy generated empirical research about children’s development, family relationships and the importance of good-quality alternative care. The ‘attachment’ concept has played a key role in professional and public awareness about the care of children and the security and organisation of attachment and mental health and as a target for therapeutic work.

Research Methodologies, Assessment and Measurement

Assessing and measuring the nature, extent and severity of mental health difficulties is an essential component of research and practice.10 Questionnaires, interviews and observational approaches help to identify the presence of disorders, including depressed mood, anxiety, traumatic responses, anti-social behavioural symptoms and concentration difficulties.

Longitudinal research identified cohorts of children at birth followed through to adulthood, establishing continuities of mental health disorders between childhood, adolescent and adult life, identifying harmful and protective influences on development. Following the development of children through to adulthood has also been a popular theme in TV documentaries.

The 1970 Isle of Wight Study, led by Rutter,11 was a key development in epidemiological research, demonstrating the value in screening whole populations and interviewing children, adolescents, young people and families. The epidemiological model has examined many influences on children and young people’s development, including prenatal factors, smoking and alcohol misuse; family factors – parental mental health, neglect and abuse, separation and divorce; and community and school influences. This knowledge has influenced public health, preventative approaches, support for parenting and clinical practice.

Measures of family and parenting relationships include attachment quality and parenting capacity. The Multiaxial Approach to Diagnosis, introduced in 1975, provided a way to describe complexity – the nature of the presenting disorder, the level of intellectual functioning, medical factors and the psychosocial factors, including family characteristics. Assessing the effectiveness of therapeutic approaches in research and practice enhances professional and public awareness of the value of treatments.

Specific Disorders of Emerging Public Interest

Self-harming suicidal behaviour, anorexia nervosa, and other eating disorders are the main mental health conditions in young people which can lead to death.12 Widely publicised tragic cases of young people with talent and promise self-harming – cutting, over-dosing, killing themselves – led to demands for improved and accessible mental health services. Increasing numbers of young people were presenting with self-starvation, distorted body image and a fear of fatness, associated with obsessive self-control of eating and calorie counting. There is continuing debate about societal aspirations for an idealised slim body shape and young people identifying with models or dancers.

Autistic disorders and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) are key neurodevelopmental disorders. Rutter delineated autism as a separate, specific disorder with deficits in social skills, empathy, problems of speech and non-verbal behaviours as well as repetitive stereotyped behaviours.13 High-functioning individuals were identified with Asperger’s syndrome and sometimes showed areas of abilities, talents and exceptional skills – for example, mathematical, musical and artistic, an interest fostered by films and TV series.

ADHD is a neurodevelopmental disorder with a classic pattern of short attention span, inattentiveness, hyperactivity, and impulsiveness, and is recognised in schools and families.14 Treatment with psychostimulants improved concentration and educational attainment and demands for treatment followed, evoking controversy about the potentially harmful effects of medication in general and on children’s growth and development.

The Recognition of Child Maltreatment: 1970s and 1980s

The Battered Child

A key to recognising child maltreatment was the publication in 1962 of Kempe and colleagues’ highly influential paper ‘The Battered-Child Syndrome’.15 Images of bruising and broken bones focused the thinking of child health practitioners worldwide. The sequence of identification in society of different forms of maltreatment followed:

Physical abuse – burns, fractures and bruises; a child ‘deserving punishment’

Neglect and failure to thrive – unawareness of the needs of the child

Emotional abuse – rejection and scapegoating

Exposure to violence – domestic violence and abuse

Sexual abuse – sexual interest and exploitation of the child and young person.

There was also the recognition that a rare unintended consequence of mothers staying with children in hospital was that, despite appearing loving and close, some came to be understood as seeking support through having a sick child. Symptoms could be falsified or exaggerated, resulting in factitious illness states – Munchausen’s syndrome by proxy or non-accidental poisoning.16

Epidemiological research revealed the extent of maltreatment, its under-reporting and the long-term impact on physical and mental health.17 Finkelhor described ‘polyvictimisation’, the exposure to multiple forms of maltreatment over childhood.18 As maltreatment can be defined as a criminal action, a social problem or a health disorder, a multidisciplinary response was advocated, led by social services. Practitioners from the police, health and social care and education were encouraged to ‘Work Together’ to recognise the signs of child maltreatment, carry out the necessary assessments, ensure the child or young person is protected though legal processes if necessary and provide intervention to help the child and family. This included appropriate treatment for complex parental mental health issues, including alcohol and substance abuse. Prosecution was reserved for the most serious injuries. There was increasing awareness of the intergenerational traumatic impact on children’s health and development and the need to provide a range of therapeutic interventions.

Recognition of Sexual Abuse

Our survey of professionals working with children in 1981 revealed that the sexual abuse of children was recognised as a crime not a focus of child protection,19 an attitude which has persisted. Following wider publication on the issue, many individuals who had suffered sexual abuse and exploitation in silence came forward to speak about their persisting traumatic experiences. There is continuing evidence about the pervasive impact of harmful sexual exploitation of vulnerable children by individuals with power – in families, communities, churches, schools, sports and entertainment.

A family and group treatment programme was established at Great Ormond Street Children’s Hospital in 1981,20 providing diagnosis and treatment for children, male and female victims, young people, protective mothers and abusive young people and parents. A rehabilitation approach based on family systemic principles was initiated, including, where possible, individuals in prison, who could take responsibility directly for abusive behaviour, albeit with stringent safeguards. A BBC Horizon documentary ‘Prisoners of Incest’ in 1984 demonstrated the approach but was controversial from feminist perspectives that raised concerns about an inappropriate accommodation to perpetrators, who were at risk of continuing abusive behaviour.

Public Recognition of Maltreatment

The reality of child maltreatment was brought home by the tragic case in 1974 of Maria Colwell, a child subjected to extensive physical abuse.21 This was the first in a series of thirty public inquiries into serious child maltreatment, with the most recent being Victoria Climbié in 2000 and ‘Baby P’ in 2009. There was extensive media coverage, detailed accounts about what had gone wrong and questioning of the current state of policy and practice. Social work professionals who had been made responsible for child protection were named, vilified and harshly criticised for accommodating to parents, failing to recognise and not using their statutory powers to protect children.

The secrecy and threat associated with sexual abuse make diagnosis through interviews and physical examination complex and challenging. In 1986, the paediatricians Hobbs and Wynne described a series of sex rings in a northern city and the criteria for diagnosis of boys and girls who had sustained anal abuse.22 The Cleveland affair in the summer of 1987 focused on the work of two paediatricians and a social worker.23 More than 100 children had been removed from their families over a short period, based in part on physical findings associated with possible sexual abuse. The findings were fiercely criticised as dubious in the media and parliament. The widely reported inquiry that followed highlighted the risk of professional intervention on questionable grounds and criticised the ‘over-enthusiastic’ use of medical science. The inquiry supported the rights of parents, in practice, undermining the attempts of practitioners to find ways to amplify the voice of the child who had been silenced. Our facilitative approach to interviews using anatomically correct dolls was also challenged.

Social Context: The Children Act

Implicit in the narrative of failure, incompetence and ‘over-zealous’ approaches to protect children were a criticism of social welfare approaches. The 1980s were characterised generally by an increasing disillusionment with the ability of the social democratic state to manage the economy and overcome a range of social problems. There was a rise in violence and a decline in social discipline. An alternative, individualised concept of relationships and market forces was advanced, aimed at shrinking the state. The family was seen as a predominantly private domain, excluding the state unless violence was being perpetrated.

This thinking underpinned the establishment of the Children Act 1989.24 The Act provided a legal framework which emphasised the importance of providing support for families and established criteria for a child being at risk of ‘significant harm’ to justify removal from a parent’s care. Mental health professionals played a key role in helping the courts understand the risks, the prospects for rehabilitation, the provision of treatment services and the possibility of the need for alternative care or, ultimately, adoption.

In parallel, the United Nation’s Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989) was established to ensure that services were provided to enable children to participate in society, to have a voice and to be protected from violence and exploitation.

Consolidation of Mental Health Services for Children, Adolescents and Young People: 1990s to 2010

Social Policy Context

This period was marked by the last phase of Thatcherism, which extended market rationalities and focused on the individual rather than governing through society.25 New Labour from 1997 to 2009 espoused the ‘third way’, combining individualism and egalitarianism and thus reconciling apparently conflicting cultural projects: personal self-realisation and rights to autonomy; and membership and community. Initiatives focused on reversing social exclusion, stressing the need for early intervention and prevention, including the Sure Start and Children’s Fund programmes. Despite significant investment, there was no full-scale attempt to reduce social inequality, although more than a million children were lifted out of poverty. The final year of this period, following the financial crash, saw the re-election of a Conservative–Liberal Democrat coalition government destined to pursue a programme of austerity, a reduction in public services, shrinking of the state and a further drive towards the privatisation of public services.

Development of Services

By the 1990s, child and adolescent mental health had a higher profile in both the public and the professional worlds. More academic chairs and departments of child and adolescent psychiatry were established, and training and accreditation programmes were developed. Research developed across the fields, including in genetics, molecular biology and neurobiology (see also Chapter 16).26

A four-tiered framework of CAMHS (Children and Adolescent Mental Health Services) as a health service was established in 1995, replacing child guidance clinics:

Tier 1 Advice and treatment provided by practitioners working in a variety of settings in the community, in general practice, in schools and in agencies working with maltreated children – e.g. the NSPCC (National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children).

Tier 2 Generic multidisciplinary teams – providing core community services for children, adolescents and young people.

Tier 3 Specialist multidisciplinary services.

Tier 4 Highly specialised services providing outpatient and inpatient care for young people presenting with early psychotic illness, eating disorders or displaying sexually harmful behaviour.

A highly specialised service that attracted much attention and controversy was the establishment of the Tavistock Gender Identity Development Service in 1989.27 Following rigorous assessments and therapeutic help, a young person’s wish to transition and develop their gender identity could be facilitated through medical and psychological intervention. During the controversy, it was asserted on the one hand that, lacking maturity, the deeply held wishes of young people should not be supported until they reached adulthood; on the other hand that there should be respect for the emerging individuality and autonomy of the young person.

The NHS organisation NICE (the National Institute for Clinical Excellence, later renamed as the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence) was established in 1999 and recommended the most effective approaches to help children and young people with mental health problems. The IAPT (Improving Access to Psychological Treatment) programme provided access to these effective therapies and was introduced to adult services in 2008 and children’s services in 2011.28 MindEd training was introduced to complement IAPT and to provide online training in emotional and behavioural ‘first aid’ and essential therapeutic skills.

One of the treatments recommended by NICE was the extensively researched CBT, with the risk that other modalities would be dismissed. Later research demonstrated that well-structured family/systemic or psychodynamic approaches were equally effective. In addition, much research focused on single disorders. The reality is that comorbid disorders are the rule rather than the exception. An alternative has been the development of integrative approaches, bringing different modalities together.29 The common treatment element approach identified and categorised common features of treatments which can be integrated to meet complex needs,30 an approach we adopted to reduce the harmful effects of all forms of maltreatment.31

Young Offenders Services

Young Offenders Services were established in 1998, with special school, youth courts, residential care and young offender institutions. However, the age of criminal responsibility remained at ten years. The world’s press had heard a blow-by-blow account of the killing of James Bulger by two vulnerable eleven-year-olds in 1993 in an adult court. Popular judgement was that the children were ‘evil’ and ‘devious’ and deserved to be in prison for life. Growing knowledge was ignored about the way the young person’s brain matures and responds to earlier trauma, undermining their capacity for judgement and control of impulsivity.

Our follow-up study of sexually abused boys demonstrated that sexually harmful adolescent or adult behaviour was more likely if they had also witnessed violence and suffered rejection.32 Attempts to change the age of criminal responsibility have been firmly resisted. The aggressive behaviour of adolescents and young people has continued to be a societal and media preoccupation – with gangs, knife crimes, bullying and ‘children who kill’.

Developments in Child Protection: Trauma-Informed Care

In 1988, in describing adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), Felitti and colleagues extended the concept of maltreatment to include household dysfunction and instability resulting from domestic violence; parental substance abuse; mental illness; imprisonment; and separation.33 They found that the more types of ACEs that individuals reported in their childhood (e.g. emotional, physical or sexual abuse; physical or emotional neglect; mother treated violently; household substance abuse or mental illness; incarcerated household member; and parental separation or divorce), the greater their risks of health-harming behaviours (e.g. smoking or sexual risk-taking) and both infectious and non-communicable diseases (NCDs), including substance abuse, mental health problems and violent behaviour.

The Framework for the Assessment of Children in Need and Their Families, in 2000, broadened the approach and provided a model for practitioners across children’s social care to describe the child’s needs in the context of parenting, individual and community factors. We were commissioned to develop and provide training in evidence-based approaches to assessment, analysis and intervention.34 Trauma-informed care in the community was introduced in 2005, integrating policies, procedures and practices as well as identifying potential paths for recovery.

The Internet: Beneficial and Harmful Influences

The World Wide Web, launched in 1989–90, gained massive popularity in the mid-1990s and was a near-instant communication aid and way of registering knowledge and information.35 The development of online therapeutic work and training has grown. Young people embraced the Internet, using it for social networking, communicating, expanding their interests, enriching their lives, entertainment, gaming, connecting and learning. Important issues, including gender identification as male, female or transsexual, could be debated. The Internet gives a voice to children and young people and may provide informal support and advice about managing specific problems, for example self-harm and anorexia.

The harmful impact of the Internet has also dominated social discourse, including exposure to age-inappropriate material online, pornography, violence or hate speech. Child pornography is circulated on the Web, and children may be groomed into creating and circulating images of sexual activities. Perpetrators have falsified their identities and groomed young people as a way of meeting and exploiting them sexually. Self-harm, suicide or anorectic behaviour can be encouraged online. Children and young people can abuse each other by sexting (sending sexual images, thus risking blackmail), cyber-bullying, harassment, disclosure of personal information or threats of social exclusion may trigger self-harm and suicidal responses.

The issue of the safety and control of the Internet is a constant and continuing theme. Childline, established in 1986, currently receives multiple calls about abuse over the Internet. Offenders can be helped anonymously to break the addictive cycle through ‘Stop it Now’.36 Children, young people and parents can be helped to understand the beneficial and harmful risks associated with internet use.

Conclusion

In their masterly review of the history of child and adolescent mental health 1960–2010 Rutter and Stevenson concluded: ‘there has been an amazing revolution in child and adolescent psychiatry … As a consequence, the body of knowledge, and the range of therapeutic interventions have increased in a way that would have seemed scarcely conceivable 50 years ago.’37 This review has confirmed these conclusions, focusing on the interface between society and mental health; promoting developments in therapeutic approaches and services to the community; and identifying and managing the pervasive and lifetime harmful impact of child maltreatment and adversity.

Key Summary Points

From the 1960s to the 1980s, in parallel to societal changes from welfarism to the counterculture, the legacy of the child guidance movement and psychodynamic approaches gave way to more active, transparent and fast-moving therapies. Family/systemic therapy involved the whole family and trained practitioners from all disciplines. Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) was developed as a new, effective psychological treatment.

Different longitudinal and epidemiological research approaches developed, providing a variety of ways of measuring the presence and impact of mental health problems. Conditions such as anorexia nervosa of childhood, self-harming and neurodevelopmental disorders – autism and ADHD – have been identified. These developments established a significant profile of child and adolescent mental health in professional practice and public awareness.

Despite attempts to ‘shrink the state’ in the 1980s, a continuing theme has been the recognition of the hidden yet pervasive traumatic impact of maltreatment many children suffer. The concept has been enlarged through the recognition of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), adding exposure to family dysfunction and instability. There is a lifespan impact of adversity on mental and physical health and a need for a trauma-informed care approach.

Fostered by an investment in social inclusion in the 1990s to the 2000s, multidisciplinary Children and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) were established, providing general to highly specialised treatment. Academic units promoted training and research in genetics and neurobiology. The National Institute for Clinical Excellence, later renamed the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, gathered the growing research information on intervention and recommended best practice.

The introduction of the Internet in the 1990s has been both beneficial and harmful. The voice of the child as a person can be amplified, including the right to determine their gender. However, the Internet may also provide a route for some people to gratify inappropriate sexual interests in children and young people and to hurt them physically and emotionally. Safety and protection require constant vigilance.

Introduction

In 1960, mentally disturbed people over about sixty years of age were widely assumed to have irreversible senility. Little attention was paid to Martin Roth’s research which showed conclusively that mentally unwell older people were not all senile but suffered from a range of disorders. In the nomenclature of the time, those were affective psychosis, late paraphrenia, acute confusion and arteriosclerotic and senile dementia.1 Only two hospitals in the UK routinely offered older people thorough psychiatric assessment and treatment. One was a ward at the Bethlem Royal Hospital led by Felix Post, primarily for people suffering from ‘functional’ illnesses, mainly depression, schizophrenia and other psychoses. The other was a comprehensive old age psychiatry service, including day hospital, outpatient and domiciliary services, plus assessment, infirmary and long-stay wards, which Sam (Ronald) Robinson established at Crichton Royal Hospital, Dumfries.

This chapter aims to explain how Roth’s, Post’s and Robinson’s ideas gradually influenced clinical practice and service provision across the UK, shifting from typical custodial inactivity and neglect of patients assumed to be irreversibly senile to the creation of proactive ‘psychiatry of old age’ (POA) services. The chapter comprises two sections: 1960–1989 and 1989–2010. The first focuses on the development of the specialty until it was formally recognised by the Department of Health in 1989. It was the subject of my PhD thesis.2 Regarding the second section, I started as a senior house officer in POA in 1989. For this section, I have also drawn extensively on the Royal College of Psychiatrists’ (RCPsych) Old Age Faculty commemorative newsletter ‘21 years of old age psychiatry’ published in 2011.3 Although the essence of much National Health Service (NHS) policy is UK-wide, specific details and implementation plans may relate to one or more of the constituent countries. Given the brevity of this chapter, I have focused mainly on developments in England.

1960–1989

Liberal ideas about personal autonomy, choice and independence emerged internationally in the 1960s. New legislation in the UK on suicide, race relations, homosexuality and abortion reflected this. Changing agendas permitted younger people to make choices, even if risky, but older people were perceived as inevitably vulnerable and, despite their experience of life, their wishes were frequently ignored. According to Pat Thane, retirement was a mid-twentieth-century change which ‘increasingly defined old people as a distinct social group defined by marginalisation and dependency’.4 Alongside negative public perceptions, retirement was associated with a marked fall in personal income and reliance on the state pension.5 With poverty came disadvantageous health inequalities.6

In the early 1960s, more than a third of psychiatric hospital beds were occupied by people aged over sixty-five. The social scientist Peter Townsend identified many older people in long-stay accommodation who ‘possess capacities and skills which are held in check or even stultified. Staff sometimes do not recognise their patients’ abilities, though more commonly they do not have time to cater for them.’7 The sheer size of wards with up to seventy beds made providing satisfactory standards of nursing care almost impossible. These wards compared unfavourably with hotbeds of activity on those for younger people which used state-of-the-art medications, psychosocial, rehabilitative and therapeutic community approaches, and planned for discharge. After the Mental Health Act 1959 (MHA), with steps taken to begin to close the psychiatric hospitals and develop alternative services in the community and in district general hospitals (DGHs), younger people were discharged leaving older people behind.

For older people, clinically and scientifically, things edged on, albeit slowly. In 1961, Russell Barton and Tony Whitehead at Severalls Hospital, Essex, established a service based on Robinson’s at Crichton Royal. In 1962, Nick Corsellis demonstrated that senile dementia had the same pathology as Alzheimer’s disease: senility was therefore not just a worn-out ageing brain but a disease process requiring further research, aiming for prevention and cure. The same year, Post published an optimistic follow-up study of 100 older patients treated for depression.8 In 1965, his textbook of old age psychiatry,9 the first of its kind, was published, and the World Psychiatric Association (WPA) hosted an international symposium in London, Psychiatric Disorders in the Aged.10 These developments provide insights into clinical, epidemiological and neuroscience achievements at the time and indicate mounting interest in older people’s mental well-being. Neuropathology was discussed in terms of air encephalograms, post-mortems and electron microscopy. There were no validated brief cognitive assessment tools, and antidepressants consisted of tricyclics, monoamine oxidase inhibitors and electroconvulsive therapy. The WPA event included remarkable and charismatic leaders such as Post, Roth and Robinson, Tom Lambo (a Nigerian psychiatrist) and V. A. Kral of ‘mild cognitive impairment’ fame (who had survived incarceration in Theresienstadt Nazi concentration camp). Among the delegates were junior doctors Tom Arie, Klaus Bergmann, Garry Blessed and Raymond Levy, all inspired by the people they met and by the academic content.

Reports of scandalously low standards of care on long-stay wards in geriatric and psychiatric institutions reached the headlines in 1967 when Barbara Robb published Sans Everything: A Case to Answer (see also Chapter 7).11 Arie, dual trained in social medicine and psychiatry, and shocked by the Sans Everything revelations, applied for a consultant psychiatrist post to work with older people at Goodmayes Hospital, Essex (‘an unposh place … Most people thought I had taken leave of my senses!’).12 Arie’s team had a low hierarchical structure and high morale, able staff were eager to join it and patients began to get better.13 Arie wrote in 1971: ‘I have never before been in a professional setting where intellectual and emotional satisfaction go more closely hand in hand.’14

Arie and a few other newly appointed POA consultants, including Bergmann, Blessed, Whitehead and Brice Pitt – a ‘happy band of pilgrims’ as Pitt called them – began to meet as a ‘coffee house’ group. The group was in the right place at the right time: in the wake of Sans Everything, the government was taking more interest in the mental well-being of older people. Through Arie’s social medicine links, including being personally acquainted with the chief medical officer, the group ‘heavily influenced’ a Department of Health and Social Security (DHSS) blueprint, Services for Mental Illness Related to Old Age (1972).15 For the growing number of old age psychiatrists, this declaration of intentions became a bargaining tool to use with the DHSS or local NHS authorities when they failed to respond to identified needs.

Since, in most hospitals, younger people were discharged and older people were not, by 1973 almost 50 per cent of psychiatric hospital patients were over sixty-five,16 far in excess of the 14 per cent in the general population. Almost two decades after Roth’s research, undiagnosed but potentially treatable conditions contributed to this, particularly depression. This was also a personal tragedy, as Whitehead explained in the Guardian:

Old people may spend their last years in dreadful misery because severe depression has been wrongly diagnosed as senile decay … If you are anxious and depressed, and more and more people start treating you as if you were a difficult child, and you are finally incarcerated in a ward full of other elderly people who are being treated in the same way, it is likely that in time you will give up and take on the role of not just a child, but a baby.17

Two events in 1973 were central to the development of POA services: the coffee house group became the RCPsych Group for the Psychiatry of Old Age (GPOA; which in 1978 became the Section for the Psychiatry of Old Age (SPOA); later the Faculty) and the international economy took a turn for the worse with the oil crisis, the stock market crash and curbs on public sector expenditure. Promises of new services for an undervalued sector of the community were particularly vulnerable to political and economic fluctuations. Reduced public spending generated competition for resources rather than collaboration. For older mentally ill people, this was further complicated by ambiguities about who should take responsibility for their care – geriatricians, general psychiatrists or old age psychiatrists. Responsibility for the care of patients with long-standing severe mental illness who had grown old in hospital was a bone of contention between old age and general psychiatrists who were ‘dead keen to get us to take their old schizophrenics’, recollected Pitt many years later. Both general psychiatrists and geriatricians were happy when old age psychiatrists took mentally disturbed older patients off their hands. Categories of ‘dementia horizontalis’ and ‘dementia verticalis’ (i.e. more mobile, restless and often disturbing to other patients, requiring much POA nursing expertise) were one way of determining who should manage which patients, but the British Geriatrics Society and RCPsych jointly created more robust guidelines for collaborative working.18

Despite liaising closely with the DHSS, POA was not officially recognised as a NHS specialty. As a result, relevant age-based mental health data were not collected because ‘sub-specialty’ statistics were ‘ignored … coded under the appropriate main specialty’.19 This resulted in excluding POA from plans, such as for training psychiatrists and appointing staff. In 1978, for example, the DHSS recommended five consultants in ‘adult’ psychiatry and one in child psychiatry for a district of 200,000 people, with no mention of POA.20 Building projects for DGH psychiatric units also overlooked older people’s needs and innovative architectural designs to promote their independence.21 Sometimes, the DHSS admitted to only including older people when it feared that not doing so would leave them ‘wide open to severe criticism’.22 A different sort of data predicament arose when statistics derived from death certificates were used as a proxy for morbidity and health needs and underpinned NHS resource distribution; ‘dementia’ was generally subsumed under ‘old age’ making it invisible.

The government’s discussion paper A Happier Old Age (1978) acknowledged that services were ‘often less than satisfactory, making effective treatment or care difficult’ and that older people should be more involved in decision-making related to their health and social care.23 The Royal Commission on the NHS (1979) recommended additional resources for older people, but these were couched negatively in terms of ‘the immense burden these demands would impose’, a reiterated defeatist sentiment likely to discourage provision. In 1979, the new Conservative government was committed to controlling inflation, reviving the economy and holding back on public spending;24 and two years later, the DHSS’s Care in the Community was subtitled A Consultative Document on Moving Resources for Care, its real objective. The emphasis was on the role of the community, self-help and families to ‘look after their own’. This was unrealistic. The challenges for carers of people with dementia were well known,25 central to the origins of the Alzheimer’s (Disease) Society (founded 1979) and reflected in the title of the book The 36-Hour Day.26

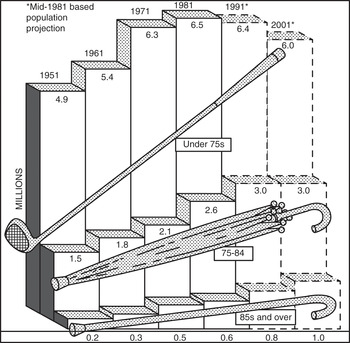

Establishing POA services was entwined with policy, politics, public opinion and stereotypes (Figure 22.1), and its leaders had to fight for every penny. Economic analyses of NHS provision tended to blame the difficulties on more older people living longer, ignoring other factors, such as rising costs of staff salaries, drugs, health technology and the cost of high dependency and palliative care at any age. They ignored increasing longevity which allowed older people to be active for more years, often contributing to the economy despite not being formally employed. The government, however, attributed rising costs of health care to remediable inefficiency within the NHS,27 which required administrative reorganisation.28 Sir Roy Griffiths, managing director of Sainsbury’s supermarkets, led a NHS management inquiry and introduced solutions from the commercial sector, particularly ‘general management’ with professional managers responsible for planning, implementation and control of performance (see also Chapter 12).29 This was particularly abhorrent to POA which had evolved almost entirely through clinical leadership. The restructuring, like NHS reforms before and since, offered rhetoric about providing for older people rather than the means to do so.

Figure 22.1 Official ageist stereotyping: ‘numbers of the elderly by broad age groups’, 1951–2001.

Amid the gloom, the ever enthusiastic and determined POA leadership found beacons of light. In neuroscience, the acetylcholine hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease emerged and the Alzheimer’s Society helped push dementia higher in public awareness and onto national policy and research agendas. Clinical POA became more multidisciplinary, adding strength to services and to previously medically led arguments on the need for them.30 The British Psychological Society established their old age special interest group in 1980. Geriatricians established the first memory clinic in 1983 at University College Hospital, London.31 Old age psychiatry was putting down academic roots, with four professors by 1986: Arie in Nottingham and Levy, Pitt and Elaine Murphy in London. Murphy became editor of the first dedicated POA academic journal, the International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, from 1986. Some hospitals established joint geriatric-psychiatric units, based on the model Arie devised and used in his professorial unit. However, the Royal College of Physicians (RCP) recommended that geriatric medicine should integrate more closely with general medicine, partly because of recruitment difficulties, and this took precedence over a holistic approach to older people’s health care.32 In 1987, older people’s mental disorders were still not routinely included in nurse training, neither were they discussed in the Royal College of General Practitioners’ Preventive Care of the Elderly. Older people were also excluded from much medical research, hazardous in the context of them being likely beneficiaries of that research.33

Each step forward had to be fought for. With the DHSS reluctant to create old age services, and with responsibility delegated to professional managers, undervalued specialties were easy to neglect. Inadequate data, ambiguities over responsibility for health care in old age, the DHSS and the main body of psychiatrists prioritising younger people before older, as well as the tendency for the NHS to prioritise physical over mental illness, ensured, intentionally or otherwise, that psychogeriatric services lagged behind. Nevertheless, the specialty grew, from a handful of old age psychiatrists in 1970, to 120 in 1980 and 280 in 1989. Old age psychiatrist Professor John Wattis, by his spurious use of statistics, commented humorously: ‘You could draw a graph which showed that the number of old age psychiatrists was increasing exponentially and by the year 2000 there would be no doctors who were not old age psychiatrists!’34 Inspiring teachers and a charismatic leadership – such as Arie, Wattis, David Jolley and Nori Graham – demonstrated POA’s truly holistic approach to health and social care and the rewarding nature of the work and drew keen recruits into it. The SPOA wanted their specialty to be recognised by the DHSS to ensure dedicated data collection, training schemes and allocation of resources but the DHSS argued against it. One reason was their fear of recruitment difficulties for an ‘unpopular’ specialty but that was incompatible with evidence of more POA consultants leading more services.

There was little movement within the RCPsych to support official recognition of POA. However, the RCP was disgruntled about older, mentally unwell people on medical wards. Sir Raymond Hoffenberg, its president, established a working party about POA services. The outcome: a recommendation by the RCP and RCPsych for specialty recognition to facilitate service developments, education, training and research. The DHSS could hardly ignore the joint recommendation.

1989–2010

In 1990, the NHS and Community Care Act enshrined the NHS purchaser/provider split and the role of social services in assessing need while delegating care to the expanding private sector (see also Chapter 10). Instead of unifying old age services, it fragmented them, especially tricky for older patients who required coordinated multidisciplinary, cross-agency care. Despite ongoing challenges, old age psychiatry services multiplied across the country but many organisational goals and individuals’ needs were still unmet. Greater provision was required.35 By 1995, more than 400 POA consultants in the UK worked mainly in comprehensive catchment area and domiciliary-based services, a tried, tested and successful model of care.

The model of service provision began to change after the first acetylcholinesterase inhibitor for Alzheimer’s disease, donepezil, was licensed in 1997. It was expensive, around £1,000 per patient per year. Dementia was prevalent, the population ageing, the potential demand excessive and the NHS required it to be rationed. In 2001, the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (now the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)) ensured this happened by recommending that donepezil be ‘initiated’ by a specialist. This was widely interpreted to mean making the diagnosis and prescribing the medication in secondary care. Memory clinics multiplied. From being mostly research-based in a few university centres, they became local diagnostic and treatment services countrywide. More technology and ‘real medicine’ may have helped to reduce stigma and encourage public discussion. However, memory clinics also had drawbacks. These included transferring people with uncomplicated dementia into secondary care rather than developing skills in primary care as for other common disorders such as depression, diabetes and hypertension. They also diminished time available for expert staff to provide the mainstay of psychosocial interventions required by patients with the most complex and distressing dementias. More resources from a finite pot going into dementia services also detracted from providing services for older people with functional mental illnesses. This was worrying when dementia affected 5 per cent of people over sixty-five at any one time, while depression alone among the functional disorders affected more than 20 per cent.36

The pattern of officialdom allowing older people’s mental health service provision to lag behind that for younger adults persisted. The National Service Framework for Mental Health (1999) was for ‘working-age’ adults. Substantial extra funding accompanied it. The National Service Framework for Older People arrived eighteen months later. It was comprehensive, including functional disorders and dementia, but without the money attached to facilitate implementation. Observing improvements made in services for younger patients caused much frustration among old age psychiatrists.

The POA leadership had to advocate persistently for older people to receive appropriate levels and ranges of care equitable with those provided for younger adults. In 2005, the RCPsych Faculty of Old Age Psychiatry pointed out that ‘liaison psychiatry’ (psychiatric services for physically unwell patients in general hospitals) for working-age adults had ninety-three dedicated consultant posts in the British Isles but, for older people, consultant liaison input was additional to their general catchment area responsibilities.37 In 2006, a joint RCPsych and RCP report stated: ‘Ageist neglect of older people with mental illness must stop.’38 It did not stop and more inequity of provision followed, such as the Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) programme (2008). IAPT was based on the premise that improved treatment of anxiety and depression for working-age adults would reduce their unemployment rates and thus pay for itself, or even generate notional surplus. IAPT excluded people over the age of sixty-five, even though they could benefit from the treatments offered. There was no acknowledgement that alleviating their mental symptoms could enable them to contribute more to society, such as in voluntary roles, and enhance independence, thus reducing the need for statutory support services, all of which could benefit the economy.

Other changes affected care for mentally unwell older people. The Mental Capacity Act (MCA) 2005 came into force in 2007. It provided a statutory framework to empower and protect vulnerable people who were unable to make their own decisions. Although idealistic and important for older people, implementing it, particularly the Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards, brought new layers of bureaucracy at great financial expense, removing resources from direct care.

The financial crisis of 2008 preceded another much-needed and well-intentioned initiative, the National Dementia Strategy,39 and probably hampered its outcome. The Strategy aimed to help people ‘live well with dementia’, by encouraging early diagnosis; improving education and research; and attending to the needs of people with dementia and their carers in the community, care homes and general hospitals. It had money attached: £150 million over two years to support implementation. This was very welcome. However, in the context of direct costs of health and social care for dementia of around £8.2 billion annually, it was a drop in the ocean. Early problems with the Strategy included a baffling range of organisations – statutory, private, not-for-profit, health and social care – and a flurry of vaguely titled new job roles such as ‘advisors’, ‘navigators’ and ‘co-ordinators’, hardly straightforward for people with dementia and their carers to negotiate. The POA activists Professors Susan Benbow and Paul Kingston observed this and commented:

sexy new solutions implemented by managers can have the opposite effect to that intended. We need to stop our headlong rush into implementation and look at the evidence for these new roles, to consider what added value they bring, and how they can be governanced and supported. Only then will we do justice to the people and families living with a dementia.40

In the wake of the Strategy, NHS England appointed Professor Alistair Burns as National Clinical Director for Dementia. Potentially beneficial, this added to the worries of many in the field of POA: should dementia be syphoned off as a separate entity, and what about the rest of old age psychiatry? Depression and psychosis in old age, key concerns for POA, were barely talked about outside specialist circles. The Strategy’s protagonists had hoped that the issue of dementia would spearhead developments to benefit older people’s mental health, well-being and dignity more broadly. The sentiments were admirable but the outcomes complex, multifaceted and mainly after 2010, so outside the scope of this chapter.

The Equality Act 2010 proved to be a hindrance as well as a help for POA: it could not abolish deep-rooted societal ageist attitudes. These contributed to (mis)interpreting the Act in ways which affected service provision, such as by depriving older people with non-dementia mental illnesses of specialist facilities and treatment and placing them instead in ‘all-age’ or ‘ageless’ services. This failed to take into account their needs which differed from those of younger people, including frailty; multiple comorbidities; risks from drug side effects and polypharmacy; different presentations of the same disorders; and different psychosocial, cultural and financial contexts.

Conclusion

Major drivers of change included dictates of fashion, supposed economy and non-validated theoretical perspectives, often imposed from a top-down template. Policies and implementation patterns derived from managerial rather than POA clinical leadership demonstrated ageist perspectives. National directives advocating uniformity of service provision could be good, ensuring access to an agreed range of services at acceptable standards and avoiding a postcode lottery. However, uniformity ignored the need for variation to fulfil local needs and undermined innovative service delivery responses. It also destroyed morale, particularly when it led to the dismantling of trusted service components which fostered expertise and humane practice, such as joint geriatric-psychiatric units, services for ethnic minority populations and long-stay NHS units for people with the most difficult to manage mental disorders. Some dismantled services required painful reconstruction when policy changed.

By 2010, there was unease about the future of the specialty. Baroness Elaine Murphy commented that some social care services, essential in POA, were in ‘meltdown’,41 and Professor Robin Jacoby wrote an article on POA called ‘Of pioneers and progress, but prognosis guarded’.42 Ageism, despite the Equality Act, plus fiercer NHS business models of health care and seeking to maintain a corporate image, contributed to the difficulties. Despite the challenges, the rewards of making the lives of older people and their families more hopeful, dignified and fulfilling, by combining individual care and aiming to improve service delivery and linked to new frontiers of neuroscience research, exemplified the interactions between Mind, State and Society and continued to attract dedicated clinicians.

In 2018, a RCPsych report was entitled, Suffering in Silence: Age Inequality in Older People’s Mental Health Care.43 In 2020, NHS England’s website stated ambiguously that older people’s mental health ‘is embedded as a “silver thread” across all of the “adult” mental health Long Term Plan ambitions.’44 Both Suffering in Silence and the ‘silver thread’ blow an icy wind of ongoing ageism and under-resourcing, failing to allow older people to have the most humane treatment and failing to learn from history.

Key Summary Points

Liberal ideas about personal autonomy, choice and independence emerged internationally in the 1960s. Changing agendas permitted younger people to make choices, even if risky, but older people were perceived as inevitably vulnerable and, despite their experience of life, their wishes were frequently ignored.

For older people, clinically and scientifically, things edged on, albeit slowly.

Promises of new services for an undervalued sector of the community were particularly vulnerable to political and economic fluctuations.

The POA leadership had to advocate persistently for older people to receive appropriate levels and ranges of care equitable with those provided for younger adults.

Ongoing and ageist themes over the fifty years have included prioritising services for younger patients; the double whammy of stigma of mental illness plus old age; and policy decisions based on short-term economic calculations rather than likely health and well-being outcomes.

The transition from asylum life to the everyday world is a stage of peculiar difficulty with the recovered patient. The home and family life to which he returns may be unsuitable or unsympathetic; employment may be hard to obtain, and friends may be unable or unwilling to help.

Introduction

The social and organisational development of community psychiatry in the UK has been covered in other chapters in this book (see also Chapters 10, 30 and 31). The best overall description of the meaning of ‘community psychiatry’, however, was provided by Douglas Bennett and Hugh Freeman in their magisterial 1991 textbook in which they outlined its principles, its origins and its progress.2 Key features of the latter were, of course, the 1959 Mental Health Act; the process of ‘normalisation’ in the asylums; the discovery of chlorpromazine and other effective psychotropic medications; and the social underpinnings of whatever was meant by the term ‘community’. The rising critique from the anti-psychiatry movement, and the notion that psychiatric illnesses were understandable reactions to social stress (rather than formal illnesses that could be medicalised), became a dominant theme (see also Chapter 20). Yet different localities proceeded at a different pace in terms of developing actual community care resources, there being no formalised process. Stumbling out of the fog of change came the Community Mental Health Teams (CMHTs) and, more specifically, in 1991, the Care Programme Approach (CPA),3 developed by the government’s managerialist Department of Health. Likewise, evaluating the effectiveness of community care teams has been extremely difficult and often very localised. Numerous thoughtful papers on the process of community care have been published (e.g. ‘Deinstitutionalisation: From hospital closure to service development’ by Graham Thornicroft and Paul Bebbington)4 and there have been endless policy papers published (e.g. Better Services for the Mentally Ill in 1975)5 as well as the National Service Framework for Adult Mental Health (NSF) in 1999,6 these rarely involving or consulting frontline practitioners (see also Chapter 12).

As a result, the term ‘community care’ has come to be mocked in, for example, TV comedies and public attitudes and has been associated with public homelessness (see Chapter 26) and inquiries into homicides (see Chapters 27, 28 and 29) as well as being considered as indicating the neglect of psychiatric services. In a 2001 paper, Julian Leff asked, ‘Why is care in the community perceived as a failure?’7 Having developed the model TAPS project for the closing down of Friern Barnet Hospital in North London,8 he admitted that ‘a comprehensive community psychiatric service, catering to all the needs of the catchment area population, exists nowhere in the British Isles and will never be achieved’. He noted at the time that few people were aware that ‘of the 130 psychiatric hospitals functioning in England and Wales in 1975, only 14 remain open, with fewer than 200 patients in each’.

From the point of view of a practising consultant psychiatrist working in the system, this chapter will therefore be an impressionistic understanding of how community care has developed and not developed and the extent to which it can be seen as a success or failure. The former is reflected in patients’ greater personal freedoms in choosing their daily lifestyles and the latter in the doubling of the prison population over the last forty years as well as the concomitant institution of numerous medium-secure forensic health units. This process has been labelled ‘reinstitutionalisation’.9 There has also been a rise in the use of the Mental Health Act and the pernicious development of ‘risk assessment’ as the driving factor in working with patients (see Chapter 27). This is despite the fact that there is no evidence that risk assessment protocols show any effectiveness in terms of predicting who will or will not go on to become a ‘mentally disordered offender’ (see also Chapter 29). One could even consider that the primary role of the asylums, to deal with the neglect and corruption of the private madhouses, has now been reversed, in that private provision for the seriously mentally ill has become dominant.

Moving into the Community

There is no clear definition of ‘community psychiatry’ apart from the belief that it is not hospital-based. The original term for it was ‘extramural’, and the initial programme involved the gradual sizing down of the asylums (often many thousand strong) into smaller units with the development of general hospital psychiatric units. Thus, in 1974, if you developed a serious mental illness in Hackney in East London you were put in an ambulance and taken to one of the larger Surrey hospitals/‘bins’ outside to the southwest of the capital or possibly to Friern Barnet in North London. By 1975, the link between Hackney and the large asylums had been broken, with the setting up of specific, local psychiatric wards in Hackney Hospital. This hospital was an old workhouse infirmary and looked as grim as anything could, but it was local.

A feature of this development was also the need to establish clear catchment area limitations for any psychiatric hospital unit, a local responsibility arrangement harking back to the old parish responsibilities of the nineteenth century. This was because the theorisation of community psychiatry seems to have forgotten that a key feature of psychiatric treatment, particularly in the inner city, was the use of the Mental Health Act for patients lacking insight into their condition and their needs – the application of the Act requiring the engagement of local social services. Thus, variably unwilling asylum physicians had to move into general hospitals (often to the dismay of fellow consultants) and try to look after CMHTs, which in themselves were undefined and variably developed. The practicalities of doing this were never carefully outlined and, although the asylum bed numbers declined gradually, the detention rates soared and the shortage of psychiatric beds (illustrated by often being 120 per cent occupied!) became a dominant concern, particularly from the 1980s onwards.

In Manchester, for example, in the late 1990s, it was reported that there were more than twenty patients detained under the Mental Health Act but awaiting admission.10 NHS resources often could not fund proper bed availability, this depending on the extent to which psychiatric professionals (especially consultants) were able to bully managers into making appropriate provision; and although CMHTs were primarily focused on looking after those with psychotic conditions (‘the new long-stay’), there grew a rising demand for the treatment of common mental health problems, which some dismissed as the concerns of ‘the worried well’. These patients were asking for help with depression and anxiety in the context of heavily advertised new antidepressant medications such as Prozac and the better recognition of the meaning of depression.

In essence, therefore, the process to deinstitutionalise and move towards community care was stumbled upon by accident, rather like the British Empire. A number of charismatic psychiatrists had led the way, for example Maxwell Jones at Belmont (his book Social Psychiatry was published in 1952; see also Chapter 20).11 Yet the practical problems of setting up a CMHT depended substantially on the goodwill between NHS and local social services. Trying to get community psychiatric nurses (CPNs), consultant psychiatrists, psychologists, occupational therapists, social workers, senior and junior, and the ‘lowly’ support workers to live and work together required immense time and effort and there were often fractures in the teams, who differed in terms of background culture, training and pay grades. Latterly, the primacy of primary care in terms of funding local resources has generated a particular demand from GPs to have CPNs and psychologists working for their primary care resource, thus further depriving specialist mental health services of staff who might otherwise have been available.

Another key feature of community care has been the regularity of shocking newspaper exposés – for example, the 1980s articles by Marjorie Wallace in The Times and the relentless publication of homicide inquiries (e.g. the report on Christopher Clunis produced by Ritchie in 1987).12 In this regard, whenever a lurid headline or TV news report announced yet another murder by a psychotic patient in the community, every thinking psychiatrist’s first reaction was to find out where the event had taken place (hoping it wasn’t in their catchment area). Fear of being called to appear before an Untoward Incident Inquiry, therefore, became part and parcel of being a consultant psychiatrist, certainly in the inner city, and the ultimate insult was when the process of inquiries was in itself privatised.

Homicide Inquiries

Homicide inquiries became the hallmark of psychiatric care in the 1980s and 1990s, gradually fading out only as pressure on the newspapers not to publish them too often started to work. This was achieved in terms of anti-stigma campaigns. The most offensive of these inquiries was the Luke Warm Luke case,13 running to some £75,000 in costs (thanks to the chair, Baroness Scotland) and several volumes of standardised prose, largely rewriting the CPA and adding nothing new to our understanding of the management of serious mental illness. The incident was due to the girlfriend of a psychotic patient refusing CMHT advice that she not visit him at home and her ending up murdered by the patient. As noted, however, the most influential report was the inquiry into the care of Christopher Clunis,14 which outlined all the problems of providing care in the community in a fractured framework of varying local mental health provision (see also Chapters 28 and 30).

Christopher Clunis was first detained in hospital in Jamaica (see Tables 23.1 and 23.2) and diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia. Subsequently, however, he was detained in a number of different hospitals, mainly in London, with diagnoses changing constantly. Like many difficult patients, he ended up with being ‘diagnosed’ as having a ‘personality disorder’. Records showed his constantly assaultive behaviours were noted but tended to improve with appropriate medication. Like many insightless patients with paranoid schizophrenia, however, he would not continue medication on discharge from hospital, and one night in North Finsbury station (in North London) he stabbed Jonathan Zito in the eye, killing him. This assault very much reflected Clunis’s own psychotic experience of feeling that people were somehow interfering with him by looking at him, and he had assaulted a number of other people in the eyes beforehand.

Table 23.1 The Clunis inquiry: diagnoses, 1986–92

| 1986 | paranoid schizophrenia |

| 29.6.87 | schizophrenia with negative symptoms |

| 2.7.87 | schizophrenia or drug-induced psychosis |

| 24.7.87 | depression |

| 1.1.88 | drug-induced psychosis, or manipulation for a bed |

| 29.3.88 | psychotic or schizoaffective illness |

| 3.5.88 | schizophrenia, drug-induced psychosis or organic illness |

| 7.6.89 | paranoid schizophrenia |

| 23.7.91 | schizophrenia |

| 5.5.92 | paranoid psychosis |

| 14.8.92 | paranoid schizophrenia |

| 26.8.92 | (diabetes) |

| 10.9.92 | normal mental state, abnormal personality |

Table 23.2 The Clunis inquiry: lengths of stays, 1986–92

| 1986 | Bellevue Hospital, Jamaica | Not known |

| 1987 | Chase Farm Hospital | 25 days, 4 days |

| 1988 | Chase Farm Hospital | 3 days, 4 days |

| King’s College Hospital | 7 days | |

| Dulwich North Hospital | 9 days | |

| Brixton prison | 21 days | |

| Dulwich North Hospital | 169 days | |

| 1989 | St Charles Hospital | 110 days |

| 1991 | St Thomas’s Hospital | 21 days |

| 1992 | Belmarsh Prison | 24 days |

| Kneesworth House Hospital | 80 days | |

| Guy’s hospital | 34 days |

The Clunis case can be seen as a template for the problems in community care. None of the members of the teams standing in the rain outside his front door trying to assess him in North London on more than one occasion had ever seen him before, thus he was able to walk out of the house without being recognised. The disjunctions of care between South and North London were noted, as was the tendency of mental health staff to downplay assaultive behaviours and their significance. The subsequent criticisms directed at the team ultimately landed with assessing him were unfair (they had minimal information and none of them had ever assessed him before), but the outline of the problems of community care was well adjudged. An important corollary was the development of a voluntary organisation called the Zito Trust (led by Jayne Zito, wife of the murdered man) which developed a full review of homicide inquiries, some 120 reports having been published by 2002, summarising and outlining them to a helpful degree.15 Like many other such voluntary organisations, for example Marjorie Wallace’s development of SANE, the general view of the concerned public was that asylums should not have been closed so quickly and that there should be more hospital beds. As noted, bed shortages have been, perversely, the dominant theme in the community care debate.

The impact of homicide inquiries on the morale of CMHTs was substantial. Staff felt stigmatised by their work and reports regularly considered failures in communication and the inappropriate use of CPA documentation as problematic. The use of complex forms to be filled in at every assessment became a negative, however, with some CPA documents taking up nine to ten pages and requiring regular reiteration when each clinical review was carried out. This was despite there being no evidence at all that filling in such a form correctly predicted the outcome for individual patients. Homicide inquiries were infused with the problems of hindsight and the counterfactual thinking generated thereby.

Along with the development of CPA and risk assessment, there was an attempt by the government in 1999 (Patients in the Community Act)16 to introduce supervision registers. These required doctors to fill in a form to determine the risk of every patient in their care, a bit like filling in the ‘proscription’ levels as noted in ancient Rome or being asked to identify potential Jews in your locality in Germany in the 1930s. Such central government impositions on practice were driven by a managerialism that has become intrinsic to NHS organisations, with little input from frontline clinicians, whether nurses, doctors, psychologists or social workers. The notion of community care as ‘outdoor relief’ or the transferring of care away to untrained staff on part-time contracts became increasingly part of our understanding of ‘care in the community’, CMHTs generally having to work out their own ways of managing patients. Heroically, supervision registers were mainly ignored.

Later Developments

In 1999, the Blair Labour government introduced the National Service Framework (NSF),17 this demanding that Trusts set up specific teams for the assessment of crisis intervention (for acute and severe mental health problems), early intervention (for patients with first-episode psychosis) and assertive outreach (for those patients whose mental ill health was thought to cause serious concern but who were not engaging with mental health services follow-up). From the organisational point of view, the need to develop a series of teams that could be specific and could not be diluted by other NHS demands (as many mental health initiatives have been) enabled the NSF and funding for it to be forced through the NHS system (see also Chapters 10 and 11). This was a clever piece of government initiative but it imposed significant limitations in terms of how mental health teams operated. In particular, the dividing up of the CMHTs into these sub-teams generated arguments as to who looked after whom and created unrealistic expectations in those given, for example, early intervention services. After being moved on from their early intervention service (with its high inputs and regular support), they were in fact referred on to the badly resourced CMHTs.

While the government’s introduction of these specialist teams was welcomed in terms of funding and resources, the role of the standard CMHT remained deracinated and uncertain. Furthermore, the crisis intervention teams took on the burden not only of seeing people in crisis (however defined) but also of being the ‘gatekeepers’ to admission to hospital. This led to arguments with consultant psychiatrists, who had known patients for many years, who were advised they had to resort to a nurse and social worker (relatively untrained compared to them) in a crisis care team to allow admission. The earlier difficulties of putting together multidisciplinary CMHTs were recreated and psychiatrists were deskilled, as their clinical activities became limited to certain interventions such as crisis management or early intervention. The ability to look after a patient right across their lifestyle and their lifetime, whether as an inpatient or outpatient, reviewed in the community, became limited. This fragmentation of services went against the standard findings of all homicide inquiry reports, namely that there should be connected services right across the spectrum.

Debates about the value of specialist teams went on in community care forums, with considerable division as to whether they were effective or not. A number of psychiatrists enjoyed the limitations of, for example, just doing assertive outreach, despite losing their skills in terms of managing patients with depression, anxiety and other non-schizophrenic disorders. Many assertive outreach teams became essentially rehabilitation teams, and a number have been gradually phased out in this context.

Overall, therefore, while the NSF engendered increased funding for psychiatry, the break-up of CMHTs generated limitations in the kind of work that could be provided. For example, new trainees found themselves either just in a crisis team or in an assertive outreach team or in an early intervention team and not seeing the overall picture in terms of management of patients with a range of conditions, in the community and in hospital wards. Thus, they missed out on being part of what has been called the ‘general psychiatry’ attitude. This imposition of excessive specialisation has been amplified by the hiving off of forensic psychiatric care into locked units (indoor psychiatry) and the push for many practitioners now to just conduct ‘primary care psychiatry’.

Primary Care Psychiatry