Meet the Editorial Board for Modern American History: Q&A with Madeline Hsu

As part of our ongoing blog series introducing the board members of the new Cambridge University Press journal, Modern American History, Madeline Y. Hsu offers her own thoughts on how she came to American history and the future of the field.

Madeline Hsu is professor of history at UT Austin, and former director of the Center for Asian American Studies. Her first monograph, Dreaming of Gold, Dreaming of Home: Transnationalism and Migration Between the United States and South China, 1882-1943 (Stanford University Press, 2000) received the 2002 Association for Asian American Studies History Book Award. Her second monograph The Good Immigrants: How the Yellow Peril Became the Model Minority was published in 2015 by Princeton University Press and has won the 2016 Robert H. Ferrell Book Prize; the 2015 Theodore J. Saloutos Book Award; the 2014-2015 Asian Pacific American Librarians Association Adult Non-Fiction Honor Book, and the 2015 Chinese American Librarians Association Award for non-fiction.

Why do you study modern American history and not something else?

Why do you study modern American history and not something else?

Actually, I am trained in Chinese history with a subfield in US immigration. I have “migrated” intellectually because my research projects are transnational in scope as I track the pathways of the Chinese Americans who are the focus of interests in migration as a human experience. In this field, it is vital to integrate a deep understanding of the local into global processes—hence my immersion into U.S. sources related to immigration and now international history. Most immigration historians, regardless of historical period, are deeply concerned with policy issues, an issue that has become even more pressing with heightened politicization of immigration and immigrants politically. My most recent projects are concerned with the Cold War as an era that I think is insufficiently understood and yet foregrounded many conditions for migration in the 21st century.

What are some of the challenges facing the field today? In what new directions might the field go?

Although it has always factored into various political positions and assertions, the teaching of history has become increasingly subject to politicized interference and reduction of resources of access. Our profession has to cope with systemic challenges to what is taught in classrooms, what kinds of analytical and interpretive models are taught, and training students with critical thinking skills. At the same time, technologies have vastly expanded our capacities to democratize access to information and resources. In addition, as a profession, historians must be more acknowledging of and proactive how history is not simply the study of “the past” but a powerful political agent with high levels of relevance for contemporary events and conditions. Working in Texas, I have first-hand experience of how politically-driven educational “reforms” have undermined K-12 educational access and curriculum, and are threatening educational integrity at the level of higher education.

If you could have been present in any “room where it happened,” what would you have witnessed?

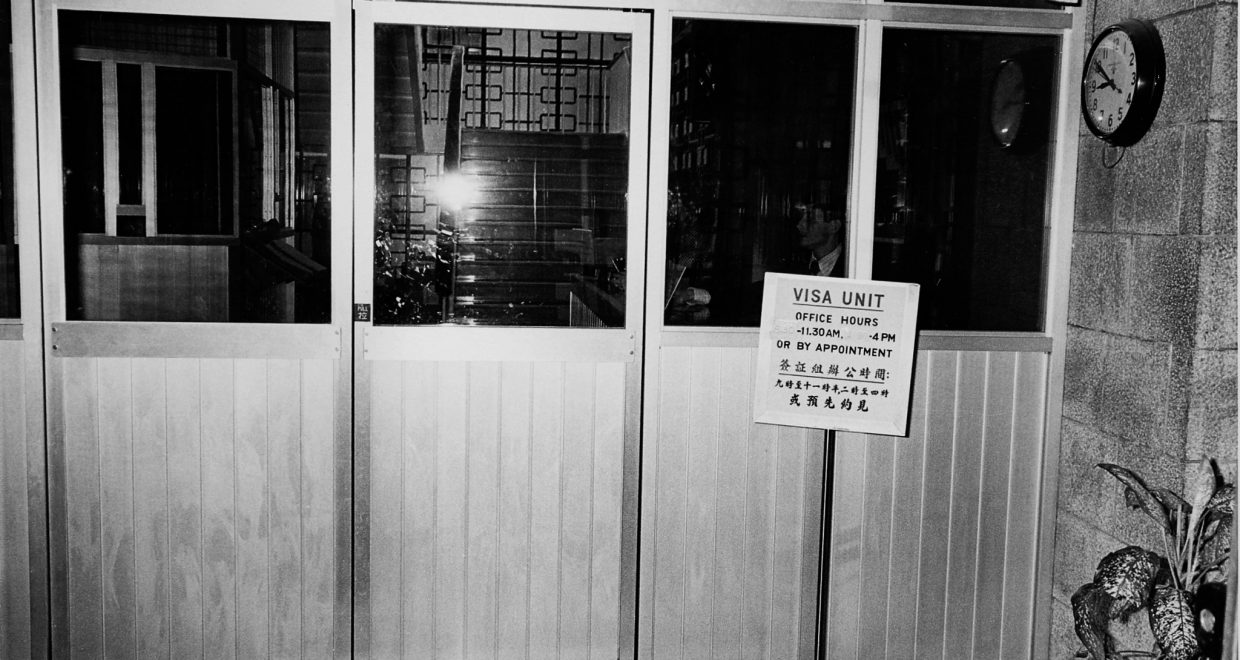

Between 1954 and 1956, the U.S. consulate in Hong Kong was juggling competing priorities in processing Chinese applications for immigration to the US. Many did so as close relatives of U.S. citizens, under the shadow of the fraudulent paper son immigration schemes, while a newer influx did so as refugees under the 1953 Refugee Relief Program which was intended to demonstrate US concern for political allies around the world. Consular staff struggled to maintain vigilant, even paranoic, scrutiny over the family reunification applications which drew upon decades of illegal immigration and was seen as a potential channel for communist spies, even as they bent over backwards to admit political refugees—particularly those with compelling life stories which could be used to publicize US international, cross-racial alliances.

These conditions highlight the ways in which inequalities in legal immigration and citizenship were increasingly implemented through the administrative handling of immigration cases, which serves to obscure racial preferences and profiling practices. This attention to institutions for immigration control highlights contemporary realities of inequitable access to mobility and legal settlement.

Modern American History’s first print issue will appear in 2018. Sign up for online content alerts and follow us on Twitter @ModAmHist. Article submissions and 250-word proposals for special features can be sent to mailto:mahist@bu.edu.

Main Image Credit: Hong Kong Chancery Office Building, 1977, National Archives at College Park