Women and Gender in Mining: Challenging Masculinity through History

This blog accompanies the IRSH Special Themed article collection

Women and Gender in Mining: Challenging Masculinity through History

The image people in the global North have of mining labour is largely based on the European coal mines of the nineteenth and early twentieth century. We tend to think of mining labour as a typically male occupation, with masculine working cultures of a distant past. What this common perception of mining labour overlooks, is that in the production of just about every modern industrial product, from smartphones to laptops, from vehicles to airplanes, a wide variety of minerals, extracted from ores, are applied. Even less well known is the fact that, in the extraction of these minerals, women are present as miners in overwhelming numbers.

Let’s take the case of mobile phones. In 2014, there were 7 billion active phone contracts, a number that equals the number of humans on earth. Tantalum, extracted from coltan ore, is one of the most important metals for mobile phones. Coltan mines are located mainly in the southern hemisphere: Australia, South America, and South Africa. Thirty per cent of the world supply of coltan is mined in 200 mines in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Here, many women and children work in artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM),with wages ranging from US $1 to $5 per day. Another example of a pivotal mineral extracted through ASM, is mica. Mica is mined in several countries around the globe, but especially in India, Madagascar (figure 1) and China. The circumstances of mica extraction are often extremely harsh, and many of the miners are women and children. Terre des Hommes recently launched a campaign to end child labour in mica mines worldwide.

Women are also important in the extraction of gold, in mines such as the Chocó in Colombia, or ones in Burkina Fasó. Nowadays Burkina Fasó is one of Africa’s main gold producers, and gold constitutes its main export commodity. Here, in 2006, 200.000 people, many of them from Niger, Mali, Ivory Coast, Ghana, Benin or Nigeria, were working in non-industrial, ASM gold mines. Gold panning is practiced by postmenopausal women in Southern Burkina, while girls and women working in goldmining in this region are mostly self-employed and live in precarious conditions. The Chocó mine (figure 2) is one of Colombia’s main sources of gold. It is located in quite inaccessible rainforest in the western lowlands of the country, which are mainly inhabited by an Afro-Colombian population that for a large part lives in extreme poverty. The region has been exploited since the colonial period. The informal mining economy here coexists with large transnational companies, and working conditions are very dangerous due to malaria, guerrilla warfare, and drug trafficking.

In Colombia, and Burkina Fasó, most of the mining is done in the form of ASM, characterized by low technology, intensive physical labour, low production rates, and poor safety, health and environmental conditions. Today it is estimated that in developing countries over thirty-five million workers, predominantly in rural areas, are engaged in mineral extraction. Women constitute an major part of this workforce.

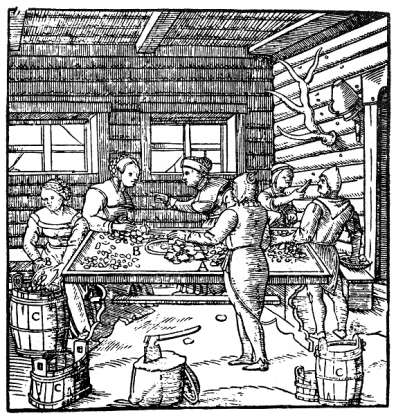

Many of the activities and tasks in ASM that women are involved in today, also existed in the past. De Re Metallica, a famous sixteenth century reference book on mining by Georgius Agricola, contains a woodcut (figure 3) depicting women who are sorting ores in the German town of Joachimsthal, which had important silver mines. From eighteenth century Japan we have similar depictions of women washing ores. Copper at that time was one of Japan’s major exports, with the VOC as its main buyer. In an 1886 etching women are shown performing surface work at the zinc mine of Scharley in Silesia (today in Poland). In British coal mines, until the mid-nineteenth century, women worked mainly in the transport of coal. They were employed to pull “hutchies”, wheeled carriages, or “slypes”, curved wooden boxes adapted to the coal seams through which they were dragged (figure 4).

It was precisely in Britain that, through different provisions, women first started to be “protected” and evicted from underground work in the mines, although they were still employed in surface work. Similar processes can be seen in other parts of Europe during the nineteenth century and the early twentieth century. The International Labour Organization adopted the first regulations concerning women in 1919, and in 1935 the ILO Convention 45 prohibited the employment of women in all underground mining activities.

Before World War II, women labourers were still crucial in the Japanese coal mines. Following the ILO Convention, however, a plan was made to reduce the number of women working in Japanese mines from 36,759 in 1928, distributed over more than 198 mines, to 8,146 working in 136 mines in 1931 and to 6,000 in 1933. The local authorities in Kyushu, the location of the important Mitsui Miike coal mine (Figure 5), where work was initially based on convict labour, requested that the eviction of women be postponed, because it would affect the livelihood of the miners’ families.

These trends to exclude women from mining, caused by changes in technology and management, but also by the emergence of a male breadwinner ideology, implied a masculinization of workplaces and work processes around the world. In large parts of the Global North, this led to the exclusion of women especially from deep mining, such as coal mining.

After 1950, however, we can see two reverse processes emerge that, in a way, are two faces of the same coin. On the one hand, in the name of equality protective laws were increasingly regarded as discriminatory against women and subsequently dismantled. Women now returned to the mines, for example in the United States. On the other hand, the development of a social welfare system in European countries had not expanded to the rest of the world, where an increasing “informal economy” gained ground, and in the process of economic globalization became increasingly linked to the commodity chain of production and to transnational companies. The mining sector in the Global South is part of this process and as a result the informal work of women has expanded throughout the mining industry.

In retrospect, women were excluded from most of the mines in the Global North during a limited period of 150 to 200 years, to reappear in the present era. Especially in the Global South women always have remained involved in mining. Nowadays, the extraction of the highly valued minerals and metals necessary for our modern high tech devices and products relies heavily on the labour of women and children, who often work under the most wretched and precarious conditions, earning incomes far below subsistence level.

The three articles in this Special Theme in the International Review of Social History take the reader from the direct involvement of women in the activities of silver production, refining, and trade in sixteenth to eighteenth-century colonial Potosí, (Bolivia), under precarious conditions), to the waged employment of women in the mines during the golden age of the mining industry in Spain (1860-1936), and then to the intersection between gender and family in the area of labour in mining areas in Greece between 1860 and 1940. Taking a long-term and global labour history perspective, the editors highlight in an extensive introduction how, historically, the concept of masculinity became so interwoven with mining labour, and how this historical image is contradicted by the historical and present reality of mining around the world.

A bibliography with relevant publications since 2006 is included to facilitate further research.