The Theatre of Purgation and the Theatre of Cultivation

Since the mid-19th century, Western drama has spread to most parts of the non-Western world. In some places it has gradually replaced the indigenous theatre; in others such as China, it has coexisted with the traditional theatre. Modern Chinese theatre is full of paradoxes.

While troupes and productions of various traditional Chinese operas outnumber Western-style dramas by a huge margin throughout most of China—with Shanghai being the only possible exception in recent years—theatre studies in China has been largely dominated by Western discourse since the early 20th century. Yet most Chinese theatre people are oblivious to the true nature and value of two main branches of Western theatre.

One of them, which originated in Greek tragedies, includes those plays with a preference for the display and purgation of those things that are undesirable. This theatre of purgation is incompatible with Chinese culture, in which theatre, especially Chinese opera, tends to showcase positive role models in uplifting stories. More in line with traditional Chinese culture and art is the second branch, which comprises a large portion of Western theatre and includes musicals, comedies, and relatively uplifting plays—theatre that shares the Chinese preference for moral cultivation.

The Western theatre of purgation is inevitably what theatre scholars and artists from the non-Western world study when they encounter the culture of the West. To make Chinese theatre prosper, however, Chinese theatre people need to pay more attention to the more mainstream Western theatre genres, which, somewhat like Chinese opera, are examples of theatre of cultivation. In the future, as Chinese and other non-Western theatremakers expand their horizons beyond the theatre of purgation by canonical theatremakers such as Euripides, Artaud, Sam Shepard, and Martin McDonagh, there will be more theatre works fusing both types of theatre.

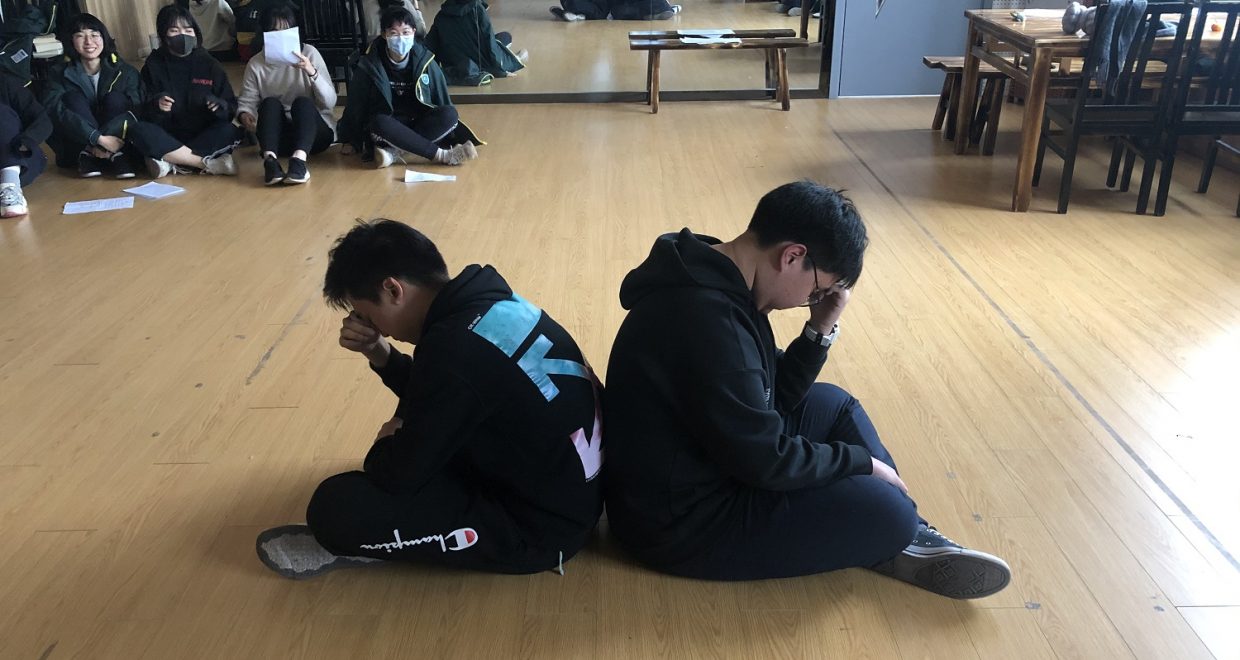

As part of our efforts at Shanghai Theatre Academy to provide theatre education to all school children—which also means bringing the “theatre of cultivation” to a wider audience—we have developed a program for school curricula, based on materials from theatre for moral cultivation. One of the best ways to help schoolchildren develop their communication skills—verbal as well as nonverbal—and learn teamwork and collegiality is to have them participate in learning and performing in dramas.

In order to make drama/theatre practice available to every student, not only elite club members, the team from Shanghai Theatre Academy has been working for the past 12 years or so to get drama classes into the curricula of all Chinese schools, and advocating that it receive the same support that music programs receive. Our team, led by myself and Shen Liang, has created several series of short plays, somewhat modeled after musical etudes. (The program is described by Shen Liang in his article “Drama Etudes: A Pedagogical Experiment in China” in TDR 65:2). These drama etudes are all rhyming playlets, each approximately 20 minutes long, to be taught in weekly 40/50-minute classes. Every student belongs to a group and is cast in a substantial role, each with a relatively equal amount of lines and actions. Based on classical literature, the themes of the etudes are universally appealing. All rhyming and rhythmic, whether sung or spoken, the lines are not only aesthetically appealing but are also easier to memorize.

Our approach stresses the importance of universality in school drama education. As we see it, one of the reasons why no place in the world has made drama class available in all schools to the extent that music classes are is that the Western educational theatre pedagogy is often too individualized to be manageable for all students in short class sessions. Our first few drama etude series—Les Mis, The Old Man and the Sea, Lu Xun’s Stories Revisited, and Confucius’s Disciples—all take advantage of the original literature’s universal themes and have been embraced by students and teachers alike in many schools, so far mainly in urban areas in a number of provinces.

We hope our pedagogical tools will be manageable for hundreds of millions of Chinese school children and their teachers who want to learn drama by doing it in their classrooms. Once they have learned from our program and developed an interest in drama, they might become active theatregoers, or even theatre-makers, helping Chinese theatre to prosper—as a result of the people’s efforts, not just the government’s. Chinese theatre will continue to be predominantly a theatre of cultivation, but through the participation of the people there will be a greater chance to develop more sophisticated Chinese theatre that fuses together theatre of purgation and theatre of cultivation.

Read the associated research article in the latest issue of Cambridge journal TDR.

Image credit – Students from Shanghai Bei Hong Senior High School in Les Misérables, part of the Drama Etudes for the Classroom program, November 2020. From “Drama Etudes: A Pedagogical Experiment in China” by Shen Liang, published in TDR 65:2, 2021. Photo courtesy of William H. Sun.