What does Mátyás Rákosi, a Stalinist Hungarian dictator, have to do with the Ottomans?

This article accompanies Adam Mestyan’s Contemporary European History article A Muslim Dualism? Inter-Imperial History and Austria-Hungary in Ottoman Thought, 1867–1921

Part of the special issue Eastern European–Middle Eastern Relations: Continuities and Changes from the Time of Empires to the Cold War

Of course, not too much. It is only a coincidence that Mátyás Rákosi studied for two years (1910–12) at the Hungarian Royal Academy of Oriental Trade, which was a specialised institution for future Habsburg Hungarian businessmen to trade with countries of the ‘Orient’. While young Rákosi studying elementary business is just a fun fact, the existence of this institution invites a number of questions about the fin-de-siècle relations between the Austro-Hungarian and the Ottoman empires, from economy to politics.

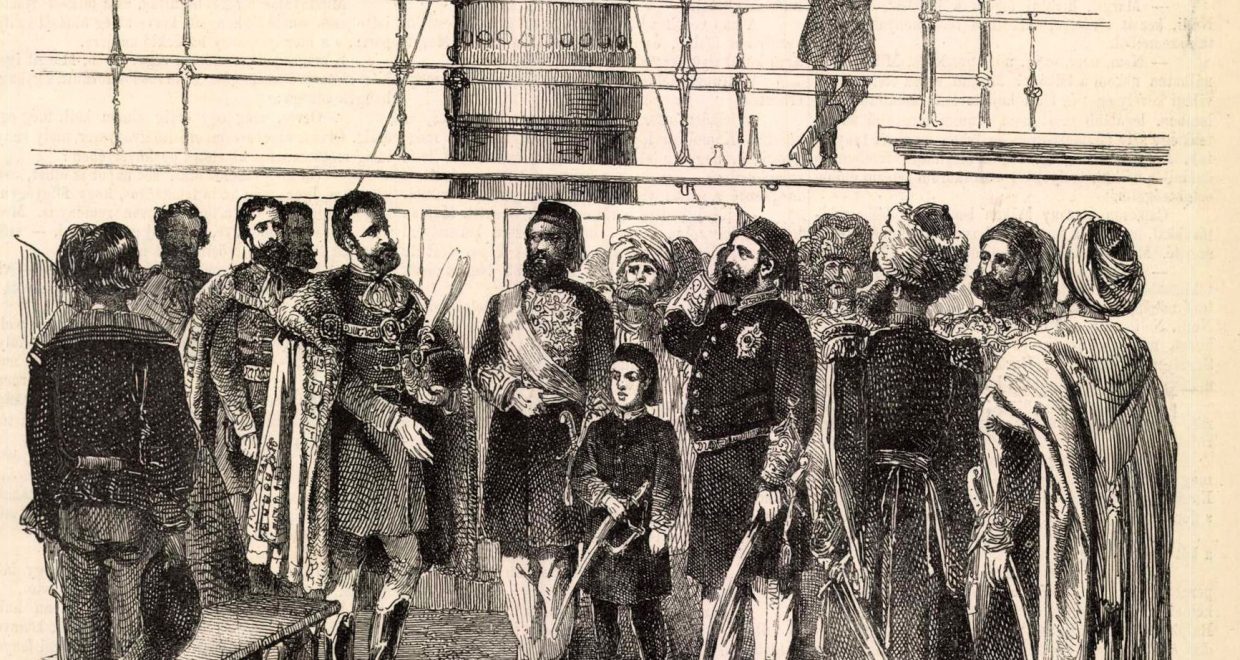

My article delves into this inter-imperial world between the 1860s and the late 1910s, before the imagined geographies of Eastern Europe and the Middle East became institutionalised historical narratives. I start with a framework for a relational history between the two empires in their last five decades. I argue that this period witnessed increased cooperation, and that this is the formative period of contemporary Eastern Mediterranean-European regionalism. Economic relations boomed between the two empires, Austria-Hungary often being the third and second importer to the Ottoman markets. Austrian and Hungarian Turcophilia was also born in this period. Perhaps it started in July 1867, when Sultan Abdülaziz, after visiting Paris and Vienna, took on a steamer in the Danube to Buda where Hungarian aristocrats celebrated the reluctant caliph in a ceremonial lunch at the moment of the Ausgleich (see main image).

To illustrate the possibilities of the inter-imperial framework, the second half of the article zooms in on one particular idea: the transformation of the Ottoman Empire along the lines of Austria-Hungary. I narrate how Ottoman thinkers used comparison for imperial reform. I describe two types of such reform visions after the 1908 restoration of the Ottoman constitution: a quickly forgotten Egyptian–Ottoman dualist idea, and a more popular, ethnic Arab-Turkish dualism. Among Ottoman Arab intellectuals, this idea was the longest living version of federal visions, surviving even the First World War. The appearance of the Austro-Hungarian composite model in late Ottoman political imagination helps to re-map the late Ottoman Empire outside of British-French dominance in global intellectual history.

Europe as a historiographical practice, which often takes nationalisms as its subject, and the European Union as its telos, confines the modern history of Habsburg-Ottoman connections to a secondary place. In contrast, one may argue that inter-imperial history is a prefiguration of contemporary relations – in fact, today’s politicians selectively use motives from the imperial past to advocate their goals. After the First World War, inter-imperial relations changed into regional cooperation among the new nation states. The cordial diplomatic relations continued between the new Turkish and Hungarian republics, both governed by formerly imperial generals – Mustafa Kemal and Miklós Horthy – who posed as civil nationalist politicians in the 1920s.