1 The Digital Yuan: A History of Multiple Layers and Scales

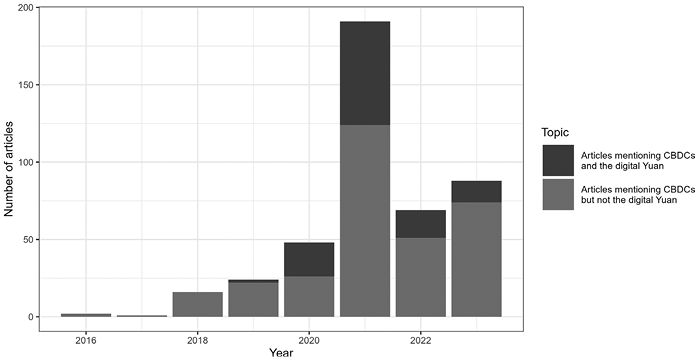

In January 2016, during an international financial conference, officials of the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) publicly announced that the Bank was working on developing a digital version of the renminbi (RMB) (Diyi Caijing Ribao 第一财经日报, 2016).1 As representatives of the Bank explained, work on the project had already begun in 2014, when the Bank set up its own digital currency task force in response to the multiplication of privately issued cryptocurrencies at the time. The task force was given the mission to examine the possible benefits accruing from the development of a digital currency backed by the Chinese state. Since this initial statement in 2016, the Chinese digital currency, even though still in its pilot phase at the end of 2023, has elicited a wealth of journalistic as well as scholarly commentary. Thus, in the specialized financial press, the digital yuan (e-CNY) has dominated discussions surrounding central bank-issued digital currencies (see Figure 29.1). Furthermore, several books have been published that are targeted toward a nonexpert readership and devote much space to discussions of the Chinese digital currency (Turrin, Reference Turrin2021; Aglietta, Bai, and Macaire, 2022; Chorzempa, Reference Chorzempa2022).

Figure 29.1 Financial Times articles mentioning CBDCs and the digital yuan, 2016–2023.

Arguably, this heightened degree of attention to the seemingly dull topic of payment systems reform (cf. Swartz and Westermeier, Reference Swartz and Westermeier2023) – of which the introduction of digital currencies is a part – stems from the weaponization of international financial infrastructures since the turn of the millennium. Thus, over the 2000s and 2010s, the payment infrastructures underpinning the global economy, which in less turbulent times operated quietly in the background, have come to the center of attention in policymaking and journalistic circles, due to their repeated instrumentalization for the enforcement and perpetuation of Western and especially American sanctions policies (de Goede, Reference de Goede2012; de Goede and Westermeier, Reference de Goede and Westermeier2022; Mallard and Sun, Reference Mallard and Sun2022; Nölke, Reference Nölke, Braun and Koddenbrock2022). Hence, payment systems reform has suddenly come to be perceived as an issue with clear geopolitical implications and thus as a topic which is relevant to a much broader public beyond financial industry professionals.

To some extent, the current geopolitical context has also affected the scholarly debate surrounding the digital yuan. Indeed, research in this field has at times strong strategic and conjectural undertones. This is apparent first of all in the fact that the current social scientific debate revolves crucially around the issue of the probable future consequences of the digitalization of the Chinese currency (Gruin, Reference Gruin2021; Huang and Mayer, Reference Huang and Mayer2022; Deng, Reference Deng2023; Peruffo, Cunha, and Haines, Reference Peruffo, Cunha and Haines2023). As a side effect, there is so far no single study about the currency’s historical origins, besides the People’s Bank’s own official account. Second, research about the digital yuan has tended to analyze the digital currency from the point of view of Western countries, questioning in particular the currency’s possible implications for the future of dollar hegemony (Zhang, Cui, and Campbell-Verduyn, Reference Zhang, Cui and Campbell-Verduyn2023). By contrast, the repercussions of the digital yuan within the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and its immediate geographical vicinity have received much less critical scrutiny. The present chapter aims to fill this gap in the literature by providing a somewhat longer history of currency digitalization in the PRC, of which the work on the digital yuan represents only the current endpoint. In this endeavor, this chapter draws on a variety of public statements by the People’s Bank as well as a selection of newspaper articles on financial reform in Chinese media.2

Following Westermeier, Campbell-Verduyn, and Brandl (this volume), we adopt the infrastructural gaze and bring the history of the digital yuan into a broader conversation with scholarship concerned with large technical systems in different societal and historical contexts. There are two benefits gained from using “infrastructure” as a sensitizing concept in the study of currency digitalization in the PRC. First of all, existing scholarship concerned with the history of large technical systems such as the Chinese digital payments infrastructure provides us with a set of assumptions concerning the mechanisms through which infrastructural change occurs. Specifically, this strand of scholarship suggests that new large technical systems are rarely ever built from scratch. Rather, new infrastructures often depend in crucial ways on existing technical systems. Thus, infrastructural change frequently operates through a mechanism which is sometimes called layering. Layering refers to the construction of new sociotechnical entities on top of already existing ones and to the reassembling of existing sociotechnical entities in novel ways. We will show that layering adequately describes several aspects of the development of a state-backed currency in the PRC.

The second advantage of exploring currency digitalization in the PRC through the infrastructural gaze is that it directs our attention toward the interplay between sociotechnical systems across multiple geographical scales (Bernards and Campbell-Verduyn, Reference Bernards and Campbell-Verduyn2019, pp. 779–780; Zhang, Cui, and Campbell-Verduyn, Reference Zhang, Cui and Campbell-Verduyn2023). Thus, at the level of the PRC, the digital yuan amounts to a network of several distinct sociotechnical entities, while at the level of the global economy the digital yuan is itself a node in an emerging network linking several payment spaces to one another. As we will show, this means that the objective socioeconomic function of the e-CNY depends, crucially, on the evolution of the structure of this emerging transnational network in which the Chinese digital payment infrastructure is embedded.

2 A History of Multiple Layers: The Digital Yuan and End of Finance as We Know It?

As a rule, large-scale technical systems evolve continuously. This change rarely ever occurs as a sudden wholesale replacement of one sociotechnical system by another (Bernards and Campbell-Verduyn, Reference Bernards and Campbell-Verduyn2019, p. 778). Rather, as infrastructure scholars Edwards, Jackson, Knobl, and Bowker have pointed out, more often than not new infrastructures are constructed on top of existing ones, so that “many infrastructures […] are themselves deeply embedded within and dependent on other infrastructures” (Jackson et al., Reference Jackson, Edwards, Bowker and Knobel2007). When infrastructural change occurs through such a cumulative process, with one type of technology being added upon another, infrastructure scholars refer to this process as layering (e.g., Reilley and Scheytt, Reference Reilley, Kornberger, Bowker, Elyachar, Mennicken, Miller, Nucho and Pollock2019). By focusing on the layered character of many sociotechnical systems, scholars can develop some critical distance with respect to assertions from social actors making overly bold claims regarding the “disruptive” socioeconomic impact of certain new technologies (Bernards and Campbell-Verduyn, Reference Bernards and Campbell-Verduyn2019, pp. 779–780). Indeed, while the notion disruption emphasizes a fundamental discontinuity between new technologies and past social practices and technological systems, the concept of layering frames technological change as a path-dependent, incremental and cumulative process (Star, Reference Star1999, pp. 381–382; Anand, Gupta, and Appel, Reference Anand, Appel, Gupta, Anand, Gupta and Appel2018, p. 12). Layering is an apt metaphor to describe how the history of currency digitalization in the PRC unfolded and, by using it, we can show how a policy proposal that had the inherent potential to completely overhaul the financial system as it exists gradually morphed into an additional layer on top of the current institutional arrangement (Larue, Fontan, and Sandberg, Reference Larue, Fontan and Sandberg2020, p. 120; Ortiz, Reference Ortiz, Fourcade and Fassin2021; Mozorov, Reference Mozorov2022).

Since the late 1990s, currency digitalization has been a topic of discussion off and on within the Chinese central bank as well as in the broader ecosystem of economic experts involved in the elaboration of financial policy in the PRC. On several occasions, the issue arose in reaction to the development of new products and services by private sector entities which facilitated payment in online retail transactions. Thus, calls for RMB digitalization often went hand in hand with statements underlining the necessity to enlarge the Bank’s purview in the quickly growing online economy, where it might otherwise be marginalized. Around the turn of the millennium, two economists of the People’s Bank, Xie Ping and Yong Lin, published a research paper raising the question of the potential costs and benefits of a publicly issued digital currency (Xie Ping 谢平 and Yin Long 尹龙, 2001). According to the two authors, the question of currency digitalization had become urgent in the wake of the steady increase in commercial transactions taking place on online platforms and due to the fact that the rise of this new internet economy had incentivized private companies to issue their own form of unregulated electronic money, in this case, prepaid cards. These two related changes could potentially weaken the efficiency of the monetary policy instruments in the Bank’s arsenal. Thus, the fundamental issue at stake in the discussion concerned the future role of the People’s Bank in an economic environment which was undergoing structural transformation. The two authors remained skeptical as to whether the central bank should attempt to provide a digital version of its currency for the sprawling internet economy or whether it should simply accept the gradual transformation of its role in a changing economic environment. Ultimately, they argued that an intervention might indeed hinder private sector innovation and would cause regulators to settle for a technologically mediocre solution.

In keeping with this skeptical line of argument, over the following years the People’s Bank maintained a relatively lenient stance toward private sector initiative in the realm of digital payments. This was evident with respect to both cryptocurrencies, and bitcoin in particular, and third-party payment providers, such as Alipay and WeChat Pay. Thus, during the early 2010s, thanks to a comparatively tolerant policy toward cryptocurrencies, China grew into the single most important global hub for bitcoin mining and trading. In December 2013, Chinese regulators made a first step toward a tightening of regulations by defining bitcoin as a digital commodity, as opposed to a currency, since it lacked legal tender status (PBoC, 2013). Nevertheless, instead of immediately shutting down bitcoin mining and trading activities on Chinese soil, authorities at first contented themselves with tightening regulations whenever the value of the cryptocurrency suddenly appreciated and the market seemed to overheat (Campbell-Verduyn, 2018, pp. 99–103). Similarly, when several technology companies, most notably Alibaba, developed their own payment services, Chinese regulators did not treat them as financial service providers at first, leaving the sector more or less unregulated (Liu, Reference Liu2021; Wang, Reference Wang2021; Chorzempa, Reference Chorzempa2022).

Toward the middle of the 2010s, against the backdrop of a general shift in regulation of digital finance and cryptocurrencies in the PRC (Wang, Reference Wang2021; Zhang, Cui, and Campbell-Verduyn, Reference Zhang, Cui and Campbell-Verduyn2023), certain reform-minded policy experts began to advocate for the development of a new nationwide state-operated payment infrastructure which could support the digital economy. Xie Ping, the coauthor of the 2001 research paper, provided an important impetus to the renewal of these discussions after having played a leading role in the reform of public shareholding (Wang, Reference Wang2015, p. 616) and having occupied a central position in the largest Chinese sovereign wealth fund. In the early 2010s, Xie coauthored a series of widely cited research articles about the digitalization of financial services in China.3 The steady digitalization of financial services had fundamental implications for the entire economy, leading to the emergence of a new regime of financial intermediation for which they coined the term “internet finance” (互联网金融) (Xie, Zou, and Liu, Reference Xie, Zou and Liu2015). Foreign observers rendered the unwieldy “internet finance” simply as “fintech” (Schueffel, Reference Schueffel2016). For Xie and his coauthors, however, “internet finance” meant something far more consequential than the mere application of new technological solutions to old problems. Rather, its emergence would amount to nothing less than a complete overhaul of the existing financial system and the consolidation of a new regime of financial intermediation which would ultimately replace the financial industry in its entirety.

Xie and his coauthors framed the rise of internet finance as a process of financial “democratization” and “disintermediation,” since the then-current “elitist” financial system conferred undue power to a small number of professionals who made far-reaching choices on behalf of their customers. In the decades to come, this industry would gradually be replaced by a single state-controlled online platform on which individual citizens could make financial decisions on their own. In their view, all financial transactions, retail as well as wholesale payments and securities transfers, would be realized via this state-operated system without the interference of any further intermediary. Indeed, as they explained, in the internet finance system “individuals and organizations (moral persons) alike will have accounts at the central bank’s payment center.” In this institutional configuration, the “system of bank accounts at commercial banking institutions would cease to exist” (谢平 Xie Ping and 邹传伟 Zou Chuanwei, 2012, p. 13).4

The term “internet finance,” as well as the idea that it was necessary to construct new public payment channels in the age of the internet economy, quickly caught on. Thus, between 2014 and 2015, then-Premier Li Keqiang repeatedly endorsed the “healthy development of internet finance” as a priority for public policy (Gruin and Knaack, Reference Gruin and Knaack2020, p. 380). However, the underlying societal project to do away altogether with the private financial sector did not gain much traction among political elites. Indeed, when the People’s Bank made its first public announcement about the digital currency in 2016, in its broad outline, the project seemed like a realization of Xie’s original proposal: It was a digital retail payment system operating on the ledger of the central bank. However, in contradistinction to Xie’s favored scenario, representatives of the People’s Bank took great care to explain that the new system would not threaten the private banking industry. Thus, in one of the earliest statements about the concrete technical design of the new digital currency in 2016, the Bank’s Vice-Governor Fan Yifei underlined that the digital yuan could in theory be developed single-handedly by the central bank, but that the Bank preferred nevertheless to cooperate with existing financial institutions since this would make implementation easier (范一飞 Fan Yifei, 2016). The first technical blueprint of the payment system was published in 2018 (姚前 Yao Qian, 2018) and confirmed this model in which private corporations and the central bank would work hand in hand, a configuration which came to be known as the two-tier model (二元体系). In this model, private sector entities would function as intermediaries between the central bank and households, purchasing the digital currency from the central bank and then distributing it, not unlike cash.

Not only did the two-tier model not undermine the fundamental role of the private financial industry in the distribution of money, it also did not threaten the economic power of the country’s two corporate giants in the field of digital payments, Alipay and WeChat Pay. Regarding the latter two, Xie Ping had once advocated a more radical proposal, arguing that the development of a public infrastructure for digital payments should be used as an opportunity to break the duopoly in the field of digital payments (谢平 Xie Ping, 2020). However, as it turned out, both companies quickly came to be associated with the digital yuan project. Thus, both Alipay and WeChat Pay developed functions to allow users of their applications to make payments via the digital yuan platform operated by the People’s Bank. Furthermore, both companies contribute to the technological development of the new infrastructure, with Alipay said to contribute its integrated development environment as well as its distributed database system, OceanBase (Liu, Reference Liu2021). Hence, whereas some of the early rhetoric surrounding the digital yuan framed currency digitalization as a means to build a new financial mechanism at the heart of the Chinese political economy, the project actually transformed into a supplementary layer in the existing “ecology of money infrastructures” (cf. Rella, Reference Rella2020).

3 The Varying Scope of the Digital Yuan and the Transnational “Race” to Develop a CBDC

In the history of the modern nation-state, infrastructures have been instrumental in logistically unifying territory (Mann, Reference Mann1984; Maier, Reference Maier2012; van Laak, Reference Van Laak2018). Yet, as Nick Bernards and Malcolm Campbell-Verduyn (2019) have underlined, the geography of infrastructures rarely overlaps with the spatial patterning of political authority. Infrastructures rarely end at the territorial boundaries of the nation-state because part of their function is to create linkages allowing for all kinds of circulation across political frontiers. Thus, even seemingly “national” infrastructures are frequently embedded in a transnational web of technical systems. The characteristics of this international network, which serves as the broader context of the infrastructure, determines the utility, function, and reach of the latter in crucial ways. The same holds true for the digital yuan, whose potential sociopolitical impact has been fundamentally altered by the rise of a transnational central bank digital currency (CBDC) movement in the latter half of the 2010s.

Following the People’s Bank’s first public statement about RMB digitalization in 2016, the project received a great deal of attention in the international central banking community and beyond. Among foreign observers, one of the key questions concerning the new Chinese payment infrastructure was how the digital yuan would affect the global balance of geopolitical and geoeconomic power. Especially in the United States, experts and policymakers were quick to interpret the People’s Bank’s work on the digital currency as a possible threat to dollar hegemony and to frame currency digitalization as a race between the major global economies, which China was then leading due to its early engagement with digital payments (Chorzempa, Reference Chorzempa2021; Himes et al., Reference Himes, Lynch, Dean, Ocasio-Cortez, Auchincloss, Barr, Sessions, Williams, Hill, Zeldin, Davidson, Gonzalez, Gottheimer, Torres, Foster, Emmer, Waters and McHerny2021). Thus, work on currency digitalization in the PRC came gradually to be perceived as a sign of the country’s economic superiority, rather than as a solution to a series of idiosyncratic problems which were specific to the Chinese payments sector.

An important aspect of this process was the rebranding of the digital yuan as a “central bank digital currency” or “CBDC.” In the second half of the 2010s,5 and especially in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, the issue of CBDCs rose to prominence in the world of central banking and financial policy (Ortiz, Reference Ortiz, Fourcade and Fassin2021; Kuehnlenz, Orsi, and Kaltenbrunner, Reference Kuehnlenz, Orsi and Kaltenbrunner2023; Swartz and Westermeier, Reference Swartz and Westermeier2023). Several international organizations, such as the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), actively contributed to the promotion of the topic by subsuming a variety of dispersed initiatives undertaken by central banks across the globe under a common label, categorizing them first as “central bank cryptocurrencies” (Bech and Garratt, Reference Bech and Garratt2017) and then later as “central bank digital currencies” (BIS Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures, 2018). The BIS in particular conducted surveys amongst central bankers about their stance toward CBDCs (Barontini and Holden, Reference Barontini and Holden2019; Boar, Holden, and Wadsworth, Reference Boar, Holden and Wadsworth2020; Auer et al., Reference Auer, Boar, Cornelli, Frost, Holden and Wehrli2021; Kosse and Mattei, Reference Kosse and Mattei2022, Reference Kosse and Mattei2023), classified existing projects to show commonalities and differences (Auer et al., Reference Auer, Boar, Cornelli, Frost, Holden and Wehrli2021), drafted scenarios for future implementation (BIS, 2021), and even actively participated in certain experimental projects via its Innovation Hub (BIS Innovation Hub, 2021). Think tanks such as the American Atlantic Council as well as journalistic outlets dedicated to blockchain and cryptocurrencies helped to draw attention to the issue of payment systems reform amongst a greater variety of actors beyond the limited community of central bankers.

While in the late 2010s, it seemed obvious to many commentators that China was leading in the race to develop a CBDC, being “the first major economy” to do so (Kumar and Rosenbach, Reference Kumar and Rosenbach2020), there was no clear-cut consensus as to what the Chinese CBDC precisely was. In a widely remarked article first published in 2019, IMF economists Tobias Adrian and Tommaso Mancini-Griffoli (Adrian and Mancini-Griffoli, Reference Adrian and Mancini-Griffoli2019, Reference Adrian and Mancini-Griffoli2021) briefly discussed the Chinese model for developing a CBDC. For the authors, the Chinese model did not, however, refer to the retail payment system which the People’s Bank had been working on since 2014. Instead, the authors focused on several regulatory changes concerning the third-party payment sector in the PRC. Their brief discussion of the Chinese model of currency digitalization described indeed what both authors termed a “synthetic CBDC.” Such a synthetic CBDC had come into being in the PRC after two related regulatory changes affecting the business model of the two main companies in the Chinese digital payment sector, Alipay and WeChat Pay.

First of all, in 2017, the central bank set up a clearinghouse, NetsUnion, which was in charge of handling all transactions made via third-party payment applications (Xing, Hei, and Pu, Reference Xing, Hei and Pu2018, p. 1221; Ba, Reference Ba2022, pp. 211–220). The reform was intended to increase the monitoring capacity of the central bank over payments realized via the firm’s applications. Before 2017, third-party payment providers such as the two technology giants had usually opened multiple accounts within the existing banking network, between which they moved funds following the transactions made by users. For officials at the People’s Bank, this meant that payments made with the applications appeared only as bulk transfers between two different bank accounts belonging to the same payment corporation. When the People’s Bank asked the companies for access to more detailed data, in some documented cases they refused (Yang and Liu, Reference Yang and Liu2019; Yu, Reference Yu2021, Reference Yu2022). After the establishment of the new clearinghouse, individual transactions made via NetsUnion applications became visible to the central bank.

In June 2018, the legal framework for the two giant payment operators changed in another decisive way, as the People’s Bank obliged both Alipay and WeChat Pay to deposit 100% of their customers’ funds in their custody into accounts at the central bank, instead of reinvesting them (Carstens, 2018, p. 9). In the PRC, neither of those measures had initially been conducted under the banner of the “digital yuan.” Yet, in conjunction, these two legal changes had led to a situation in which payments made via WeChat Pay and Alipay came to bear characteristics similar to those described in blueprints for CBDCs: Retail payments with the two applications could be monitored by the central bank and they were realized with liabilities entirely backed by reserves. This institutional setup was the “Chinese model” of constructing a CBDC, according to the IMF’s researchers (Adrian and Mancini-Griffoli, Reference Adrian and Mancini-Griffoli2019, Reference Adrian and Mancini-Griffoli2021). The “Chinese CBDC,” thus defined, neither necessitated the use of any new technologies in the realm of payments, nor commanded any considerable amount of public investment in the construction of a novel infrastructure. Rather, for the creation of a synthetic CBDC in the PRC, it had been sufficient to impose tighter regulations on formally private entities already operating in the field of digital payments.

Within the Chinese politico-administrative elite, the label “CBDC” was not uncontested. While certain Chinese governmental agencies willingly took up the idea that China was leading in the race to develop a CBDC (State Council of the PRC, 2019), in 2020, former Governor of the People’s Bank, Zhou Xiaochuan, explicitly refuted the notion that the digital yuan was a CBDC (Zhou, Reference Zhou2020). Zhou argued that the key difference between the digital yuan and an ideal-typical CBDC lay in their respective liability structures: Whereas CBDCs were ultimately the liability of the central bank, the digital yuan would be a liability of the private financial sector backed by some amount of central bank reserves. This view was ultimately contradicted upon the June 2021 publication of a white paper on the digital yuan in which the People’s Bank stated that the digital yuan was actually its own liability and that the private sector would merely be charged with distributing it. Furthermore, the white paper explicitly labeled the digital yuan as a “retail CBDC” (Working Group on E-CNY Research and Development of the People’s Bank of China, 2021, p. 4). The digital yuan had thus become a CBDC and the People’s Bank the leading institution in the transnational race toward monetary modernity.

The rise of a transnational CBDC movement had thus led to an accumulation of symbolic capital by the People’s Bank. The second, and arguably more important, consequence of the multiplication of CBDC initiatives across the globe was the fact that it created a new window of opportunity for Chinese policymakers to reconsider the purpose the Chinese digital currency might serve. Most notably, it opened up new possibilities for the digital yuan to contribute to the broader restructuring of international financial infrastructures and thereby to strengthen the RMB’s role in the global economy. From early on, officials at the People’s Bank had repeatedly refused the notion that the digital yuan was intended to alter the function of the currency in the international monetary architecture. Thus, Mu Changchun, head of the central bank’s digital currency institute stated that there was no direct causal link between the international use of the Chinese currency and its material form (Mu, Reference Mu2020). According to Mu, international use depended first and foremost on economic fundamentals and then other structural variables of the economic system, a position which has found multiple echoes in the scholarly community (Prasad, Reference Prasad2021; Eichengreen, Reference Eichengreen2022; Peruffo, Cunha, and Haines, Reference Peruffo, Cunha and Haines2023). Similarly, former People’s Bank Governor Zhou Xiaochuan reiterated this point, stating during a public conference that the initial intention of the project had never been to influence international wholesale payments (Xu Wei, 2022). Rather, the digital yuan had been conceived with “shopping in mind” and the cross-border use of the digital yuan would probably remain limited to small retail transactions.

However, against the background of payment system reform in other countries, the digital yuan could become a tool to experiment with new ways of linking the Chinese payment system to systems operating in other jurisdictions. In early 2021, the People’s Bank publicized its participation in a joint collaborative “multiple CBDC” project conducted in partnership with the Bank of Thailand, the Bank of the United Arab Emirates, and the Monetary Authority of Hong Kong: Project mBridge. The explicit aim of the collaboration was to establish a shared platform for interbank settlements in all four jurisdictions based on a commonly operated blockchain. In the first joint report about the advancement of the project, Mu Changchun argued that mBridge was yet another threshold in the brief history of the digital yuan. In the same context, he stated once more that the currency was first and foremost a payment instrument for domestic retail transactions (BIS Innovation Hub, 2021, p. 13). With Project mBridge, the digital yuan had, however, acquired an undeniable transnational dimension.

4 Conclusion

This chapter has provided a brief history of currency digitalization in the PRC since the turn of the millennium by drawing on a variety of publicly accessible sources including newspaper and journal articles. In this endeavor, we have borrowed insights about the dynamics and mechanisms of infrastructural change from a selection of works by scholars concerned with the development of large technical systems in other societal and historical contexts. Application of this “infrastructural gaze” has helped us to formulate two distinct arguments. First of all, in a way similar to many other large societal infrastructures, during its early years the construction of the digital yuan was at times presented as a means to completely overhaul existing sociotechnical systems. Yet, when work on the project began in earnest over the second half of the 2010s, a process of layering unfolded, whereby the digital yuan came to rely on already existing sociotechnical systems. Second, not unlike other sociotechnical systems, the digital yuan is embedded in a transnational network of financial infrastructures which crosses national boundaries. The nature and structure of this transnational network determines in crucial ways the ultimate sociopolitical function that the digital yuan plays and will play in the international political economy.