This chapter briefly reviews core ideas and research results in the existing instrumental stakeholder theory (IST) literature and then applies the IST concept to the simultaneous pursuit of two objectives – advancing social welfare, the presumed goal of morally legitimate social systems in general, and preserving the key elements of shareholder wealth enhancement, the traditional goal of the corporation.1 In so doing, we expand the range of ethical approaches to IST beyond deontological principles (e.g., treat stakeholders fairly; be trustworthy in dealing with stakeholders) present in extant versions of IST, to a consequentialist focus (i.e., a utilitarian concern for “the greatest good for the greatest number”). Our analysis leads to a suggestion for a modified corporate objective and lays out several research questions as a starting point for a new research agenda.

Instrumental Stakeholder Theory as Originally Envisioned

Donaldson and Preston (Reference Donaldson and Preston1995) suggested that stakeholder theory has three interrelated but distinct perspectives. The descriptive/empirical perspective provides accounts of how firms, their managers, and their stakeholders actually behave. Normative theory deals with the moral aspects of this behavior – i.e., how firms/managers/stakeholders should behave. Instrumental stakeholder theory (hereafter IST) proposes theoretical connections between particular stakeholder management practices and resulting end states. Specifically, IST suggests that firms that treat their stakeholders ethically will enjoy higher profit performance (and presumably higher returns for shareholders) than firms that do not. Although examining a theory from multiple perspectives may be a useful intellectual exercise, the normative implications of stakeholder theory are foundational to all forms of the theory (Donaldson & Preston, Reference Donaldson and Preston1995; Jones, Reference Jones1995). The normative aspects of IST most clearly differentiate it from other possible management approaches – it is based on ethical treatment, and consideration of what is or is not ethical, in the stakeholder context, is obviously a normative exercise.

Core Elements of Instrumental Stakeholder Theory

Ethical management principles upon which extant IST is based include the notion that firms should conform to widely accepted rules of society, but also include principles such as fairness, trustworthiness, respect, loyalty, care, and cooperation (Greenwood & Van Buren, Reference Greenwood and Van Buren2010; Hendry, Reference Hendry2001; Jones, Reference Jones1995; Phillips, Reference Phillips2003). Jones (Reference Jones1995) developed a strong rationale to support the notion that ethical treatment of stakeholders reduces contracting costs between firms and stakeholders. First, from an agency cost perspective (Jensen & Meckling, Reference Jensen and Meckling1976), ethical treatment can reduce monitoring costs because the actors can trust that the basic terms of the agreement will be satisfied. Second, bonding costs will be reduced because actors do not have to worry about opportunistic behavior; that is, taking actions that harm the other party. Third, residual losses will be reduced because monitoring and bonding may not completely address the interests of both parties. Similarly, from a transactions cost perspective (Williamson, Reference Williamson1975), ethical treatment can reduce costs associated with searching for an adequate trading partner, lengthy negotiation processes, high levels of monitoring, costly enforcement mechanisms, and, again, residual losses. Ethical treatment also addresses moral hazard, or the risk that one of the parties may shirk their responsibilities (Alchian & Demsetz, Reference Alchian and Demsetz1972), as well as hold up problems stemming from a reluctance of one of the parties to make specialized investments, which could impede progress.

Along these same lines, Bridoux and Stoelhorst (Reference Bridoux and Stoelhorst2016) argue that communal sharing relationships between firms and stakeholders provide a highly efficient production model. These types of relationships are characterized by high levels of trust, shared goals, willingness to share even proprietary information, a high level of cooperation, and an emphasis on relational (as opposed to arms-length formal) contracts. These relational characteristics increase efficiency by reducing contracting costs, making maximum use of information available anywhere in the production system, reducing or eliminating enforcement costs, and increasing the motivation and loyalty of stakeholders. These sorts of benefits would seem to be sufficient to motivate a large proportion of firms to pursue strategies that result in communal sharing relationships with stakeholders, yet they tend to be somewhat rare. Jones, Harrison, and Felps (Reference Jones, Harrison and Felps2018) explain that this is because they are difficult to execute successfully and also very hard to imitate. However, it is these very characteristics – rarity and inimitability – that gives them the potential to lead to a sustainable competitive advantage. Also, there is a wealth of theory that suggests that there are economic benefits to ethical treatment of stakeholders, even short of full communal-like treatment (Freeman, et al., Reference Freeman, Harrison, Wicks, Parmar and de Colle2010). As the next section will demonstrate, the empirical evidence tends to support the idea that, on average, the performance advantages of IST-oriented treatment of stakeholders outweigh the costs.

In addition to the arguments put forth by Jones (Reference Jones1995), and further developed by Bridoux and Stoelhorst (Reference Bridoux and Stoelhorst2016) and Jones, et al. (Reference Jones, Harrison and Felps2018), ethical treatment of stakeholders can reduce costs associated with negative stakeholder actions such as boycotts, walkouts, strikes, adverse regulation, bad press, and legal suits (Cornell & Shapiro, Reference Cornell and Shapiro1987; Harrison & St. John, Reference Harrison and St. John1996; Shane & Spicer, Reference Shane and Spicer1983). This also makes a firm less risky for investors, which can enhance the value of its securities (Graves & Waddock, Reference Graves and Waddock1994). In addition, reduced risk makes a firm a more attractive investment partner, whether the investments are in the form of cash invested by stockholders or financiers, suppliers entering into new contracts, or specific investments made by employees in the firm (Wang, Barney, & Reuer, Reference Wang, Barney and Reuer2003). As firms develop ethical reputations, stakeholders will want to engage with them, customers will want to buy their products, more people will want to become their employees, governments will be less likely to closely scrutinize and regulate them, and communities will find them more attractive as local partners (Hosmer, Reference Hosmer1994; Jones, Reference Jones1995; Post, Preston, & Sachs, Reference Post, Preston and Sachs2002; Roberts & Dowling, Reference Roberts and Dowling2002). The surplus of desirable and willing stakeholders with whom to engage can enhance a firm’s ability to acquire and develop resources leading to competitive advantage (Post, et al., Reference Post, Preston and Sachs2002), and its ability to coordinate multiple contracts simultaneously (Freeman & Evan, Reference Freeman and Evan.1990). The firm will also have a greater ability to discover ways to produce stakeholder synergy, the simultaneous creation of value for multiple stakeholders through one decision or action (Tantalo & Priem, Reference Tantalo and Priem2016).

Organizational justice considerations also suggest a positive relationship between ethical stakeholder treatment and firm performance (Harrison, Bosse, & Phillips, Reference Harrison, Bosse and Phillips2010). A firm that exhibits distributional justice will allocate value fairly to the stakeholders that helped to create it. Procedural and interactional justice help stakeholders feel valued, and can reduce the possibility of negative actions. All of these forms of justice can result in reciprocity in the form of higher levels of stakeholder motivation, loyalty, and cooperation (Bosse, Phillips & Harrison, Reference Bosse, Phillips and Harrison2009). Also, organizational justice increases trust, and thus the willingness of stakeholders to share information about their own utility functions with the firm. The firm can use this stakeholder utility information to create more appealing value propositions, to generate higher levels of efficiency and productivity, and to guide innovation efforts (Harrison, et al., Reference Harrison, Bosse and Phillips2010). As an additive effect, as a firm treats a particular stakeholder well, other stakeholders who are aware of the treatment may also reciprocate toward the firm, a phenomenon called generalized exchange (Ekeh, Reference Ekeh1974).

Of course, the sort of stakeholder treatment discussed in this section is not without incremental costs. Some of these costs include a generous allocation of value to stakeholders, the risk that stakeholders may not reciprocate, the cost of holding onto stakeholders that no longer provide adequate value to the value creating process, the additional time and other resources that must be devoted to managing relationships with stakeholders, and higher information management costs resulting from the additional information acquired from stakeholders and required to manage relationships with them effectively (Bridoux & Stoelhorst, Reference Bridoux and Stoelhorst2016; Garcia-Castro & Francoeur, Reference Garcia-Castro and Francoeur2016; Harrison & Bosse, Reference Harrison and Bosse2013; Jones, et al., Reference Jones, Harrison and Felps2018; Sisodia, Wolfe & Sheth, Reference Sisodia, Wolfe and Sheth2007). In fact, it is probable that some firms experience higher performance because they take advantage of a strong bargaining position in their interactions with stakeholders (Bridoux & Stoelhorst, Reference Bridoux and Stoelhorst2014), a cost in lost opportunities to firms that eschew the use of bargaining advantages. Along these same lines, heterogeneity among stakeholders with regard to their preferences regarding equity and the extent to which they reciprocate mean that the benefits stemming from excellent treatment of stakeholders may not exceed the costs of doing so (Hayibor, Reference Hayibor2017).

Because of cost factors, managers need to be careful not to “give away the store” in their efforts to please stakeholders. Harrison and Bosse (Reference Harrison and Bosse2013) provide theory that suggests when firms may be over- or under-allocating value to stakeholders, from a firm performance perspective. Also, Jones, et al. (2018) suggest that the benefits associated with IST-based stakeholder treatment are more likely to exceed the costs in high-velocity industries, knowledge-intensive industries, and in contexts in which there is high task and outcome interdependence.

The Empirical Evidence

A large body of evidence demonstrates that firms that practice IST principles tend to have higher financial performance. Freeman, et al. (Reference Freeman, Harrison, Wicks, Parmar and de Colle2010) provided an extensive review of the empirical evidence on the performance of firms that practice IST principles up to the date their book went to press. Among the most compelling of the studies they reviewed was an early study by Preston and Sapienza (Reference Preston and Sapienza1990), who found that firms that serve the interests of multiple stakeholders (shareholders, employees, community, and customers) had ten-year rates of return that were positively correlated with each of their stakeholder variables. Also important, Berman, Wicks, Kotha, and Jones (Reference Berman, Wicks, Kotha and Jones1999) examined whether it is an instrumental motive (treating stakeholders well enhances performance) or an intrinsic motive (all stakeholders have inherent worth) that tends to drive financial importance. They found some evidence to support the IST motive and no support for the intrinsic motive. In addition, Hillman and Keim (Reference Hillman and Keim2001) distinguished between stakeholder management attributes and social attributes (dimensions associated with socially desirable behaviors), and found that the stakeholder management attributes had a positive effect on shareholder value creation. Finally, Sisodia, Wolfe, and Sheth (Reference Sisodia, Wolfe and Sheth2007) conducted an exhaustive study in which they identified firms that were universally admired by a broad group of their stakeholders, and found that these firms also had high financial performance over a variety of time frames. Studies that examined the relationship between financial performance and the salience given to particular stakeholders by management have been less conclusive (i.e., Agle, Mitchell, & Sonnenfeld, Reference Agle, Mitchell and Sonnenfeld1999).

More recently, additional empirical evidence has established a strong link between stakeholder-based management and financial performance. Choi and Wang (Reference Choi and Wang2009), using a very large sample, found support for the idea that good stakeholder relations have a positive effect on persistent superior performance. In addition, they discovered that such relations can help a firm recover from inferior performance. In another important study set in the gold mining industry, Henisz, Dorobantu, and Nartey (Reference Henisz, Dorobantu and Nartey2014) found support for the notion that financial markets take stakeholder relations into account when determining the value of increases in resource evaluations (or the expected increase in resource evaluations) of different mines, providing evidence that good stakeholder relations can enhance firm efficiency and reduce operating risk, and that market participants observe and react to the quality of relations between a firm and its stakeholders.

As mentioned previously, generalized exchange is an important assumption of IST. That is, the way a firm treats one stakeholder can influence the way other stakeholders respond to the firm. Cording, Harrison, Hoskisson, and Jonsen (Reference Cording, Harrison, Hoskisson and Jonsen2014) found support for this assumption in a post-merger context, a time when organizations are in tumult, implicit contracts are at risk of being violated, and stakeholders are likely to feel vulnerable. Finally, and consistent with the notion that there are both benefits and costs to IST-based stakeholder management, Garcia-Castro and Francoeur (Reference Garcia-Castro and Francoeur2016) examined the notion that there are rational limits to the size of investments firms make in stakeholder relations. Among their important findings, they concluded that stakeholder investments are more effective when they are done simultaneously across a firm’s high priority stakeholders and when no single stakeholder group is provided with a disproportionately high investment. In addition, they discovered that there are lower bounds for stakeholder investments for firms with very high performance, evidence that neglect of even one important stakeholder can hold back performance. They also found contextual effects associated with different types of strategies and national settings.

Adding the findings from these four studies to previous empirical work, we continue to see evidence for a positive relationship between IST-based management and firm performance, and for the existence of a generalized exchange effect. There is also evidence that context matters, and that there are situations in which stakeholder management based on IST principles may actually reduce firm performance, or at least that over-investment in stakeholder relations can suppress performance. There is, of course, variance in performance for firms that practice IST in their relations with stakeholders, and the field is only beginning to explain this variance.

One interesting, but not fully explored concept, is that because IST is built on a foundation that encourages ethical treatment of a broad group of a firm’s stakeholders, and discourages behavior that destroys value for any of its stakeholders, a management approach based on IST may offer the potential to genuinely increase social welfare (Jones, et al., Reference Jones, Donaldson, Freeman, Harrison, Leana, Mahoney and Pearce2016). In other words, a stakeholder perspective may offer the potential to enhance shareholder welfare and social welfare simultaneously. This notion will be explored in the rest of this chapter.

Shareholder Welfare and Social Welfare

Originally based on work dating back centuries (Smith, Reference Smith1776/1937), reinforced at the dawn of managerial capitalism (Berle & Means, Reference Berle and Means1932), famously and stoutly defended by a Nobel Laureate (Friedman, Reference Friedman1970), and more recently reformulated (Jensen, Reference Jensen2002; Jensen & Meckling, Reference Jensen and Meckling1976), the primary objective of the corporation has been the maximization of profit (more recently, shareholder wealth). This objective has the advantages of being clearly stated, theoretically achievable since it is single-valued, considered to be morally grounded in utilitarian moral philosophy, and backed by the imperatives of equity investors – “Wall Street.”2 Unfortunately, achieving shareholder wealth maximization is far more complicated than describing it (Freeman, Wicks, & Parmar, Reference Freeman, Wicks and Parmar2004). While there are many ways to increase shareholder wealth, no single formula exists for maximizing it.3

Importantly, although some may consider shareholder wealth maximization an appropriate objective of the firm, it is not the objective of society as a whole. Rather, it is a part of an economic system – market capitalism – intended to advance social welfare. Put differently, it is one of the means by which the end – social welfare – is pursued. In fact, existing in parallel to the conclusion that the primary objective of the firm is to maximize shareholder welfare is a widely accepted view that the advancement of social welfare, through wealth creation, is the defining function of business in a market capitalist system (Barney, Reference Barney1991; Jensen, Reference Jensen2002; Wallman, Reference Wallman1998). Walsh, Weber, and Margolis (Reference Walsh, Weber and Margolis2003) make an explicit claim regarding the central importance of social welfare in management research, calling the economic and social objectives of business the raison d’être of corporations. Indeed, the role of profit seeking/maximization in the advancement of social welfare appears in statements by two prominent economic thinkers – Adam Smith and Michael Jensen. In his discussion of the invisible hand of the market, wherein individual self-interested behavior leads to socially beneficial outcomes, Smith famously wrote:

It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker, that we can expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest … He is in this, as in many other cases, led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention. Nor is it always the worse for the society that it was no part of it. By pursuing his own interest he frequently promotes that of the society more effectually than when he really intends to promote it.

Contemporary expressions of this relationship, specifically involving the maximization of shareholder wealth, are represented in the words of Michael Jensen:

Two hundred years of work in economics and finance implies that in the absence of externalities and monopoly (and when all goods are priced), social welfare is maximized when each firm in an economy maximizes its total market value.

Both Smith and Jensen make it clear that profit seeking (Smith)4 and market value maximization (Jensen)5 are means to a larger end – social welfare.6

With these two important objectives in mind, we now consider whether they can be maximized simultaneously. Traditionally, in accordance with neo-classical microeconomic theory, profit maximization on the part of firms was thought to assure that social welfare was also maximized. Unfortunately, recent work in stakeholder theory (e.g., Jones & Felps, Reference Jones and Felps2013a; Jones, et al., Reference Jones, Donaldson, Freeman, Harrison, Leana, Mahoney and Pearce2016; Mitchell, et al., Reference Mitchell, Weaver, Agle, Bailey and Carlson2016; Freeman, et al., Reference Freeman, Wicks and Parmar2004) has thoroughly debunked the notion that corporate profit maximization inevitably leads to maximal social welfare. Indeed, in some cases, this objective may lead to decreases in social welfare. If profit maximization (leading to high shareholder returns) as a corporate objective is an unreliable path to maximal social welfare, is there an alternative single-valued objective that could serve the end of maximal social welfare? One proposed alternative – stakeholder happiness enhancement (Jones & Felps, Reference Jones and Felps2013b), while also grounded in utilitarian precepts, presents some thorny measurement problems and has garnered little scholarly traction. Indeed, the search for a single-valued corporate objective that will (at least in theory) produce maximal social welfare remains an elusive goal. Therefore, even when social welfare is viewed exclusively in terms of economic value, its pursuit is highly contingent. This conclusion is greatly amplified by the observation that social welfare cannot realistically be viewed in economic terms alone. Concerns about stability and justice (Marti & Scherer, Reference Marti and Scherer2016) and several other dimensions of welfare (Mitchell, et al., Reference Mitchell, Weaver, Agle, Bailey and Carlson2016) are also legitimate considerations in any discussion of social welfare. To sum up, maximal social welfare cannot be achieved through the application of a single-valued objective, like maximizing shareholder returns; enhancing social welfare is a highly contingent undertaking.

Which Objective Should Prevail?

Given that the profit maximization objective of the firm and the wealth creation function of business in the economy will sometimes work at cross-purposes, which of the two goals should take precedence? We posit that when profit maximization leading to high shareholder returns and aggregate wealth creation for all stakeholders (including shareholders) come into conflict, the latter should prevail. Policies intended to create wealth for one stakeholder group, shareholders in this case, should not destroy wealth overall. In our view, the fundamental purpose of business in a market capitalist economy – i.e., creating wealth for society as a whole – should be preserved irrespective of the imperatives of individual businesses. Why? First, business, as an institution, is instrumental – a means to an end (Smith, Reference Smith1776/1937; Jensen, Reference Jensen2002; Wallman, Reference Wallman1998). The end of business activity is the improvement of social welfare in general and of economic welfare in particular.7 If the appropriate end of business activity is social welfare, and profit maximization leading to high shareholder returns is only a means to that end, when the two objectives conflict, social welfare through total wealth creation should supersede profit maximization that is intended to maximize shareholder returns.

Furthermore, it is almost an axiom of social theory that social institutions must be supported by some legitimating moral logic or society will no longer permit them to exist. In other words, social institutions must have a purpose that is not simply the perpetuation of the institution itself or the advancement of the interests of the beneficiaries of its existence. For example, democratic political institutions in general are legitimized by their reliance on the consent of the governed, not by their ability to bestow benefits on a few favored groups. Similarly, legal institutions are legitimized by their quest to produce a substantial measure of justice – protecting the citizenry in general as well as those accused of transgressions – not by their ability to enrich attorneys or employ other legal functionaries (e.g., judges, bailiffs, and court reporters). Economic institutions, by an analogous logic, are legitimized by their ability to produce economic wealth for society writ large, not just for shareholders or top executives. Although this logic can take many forms, it must be compelling to at least a significant majority of those affected by the institution in question.

Another perspective on legitimacy is also relevant to the choice of economic objectives – in this case, shareholder wealth vs. aggregate wealth creation/social welfare. In a classic analysis of corporate legitimacy, Hurst (Reference Hurst1970) posited the existence of two possible foundations for the legitimacy of social institutions – utility and responsibility. Of the two, utility is most relevant to this discussion. Underlying this analysis, and much economic theorizing in general, is the moral concept of utilitarianism – the improvement (ideally maximization) of social welfare/utility, popularly (but imprecisely) described as “the greatest good for the greatest number” (Mill, Reference Mill1863; Bentham, Reference Bentham1823/1907; Sidgwick, Reference Sidgwick1879). A social institution has utility if it promotes an end valuable to society. Economic welfare is such an end. Most US citizens would endorse the social usefulness of promoting economic welfare. The same cannot be said for shareholder wealth maximization per se. A social institution dedicated solely to increasing the wealth of those who own shares in corporations would not be regarded as legitimate by many citizens. Therefore, we conclude that economic welfare should always be preserved as corporate policies focus on maximizing (or increasing) shareholder wealth. This is not the same as concluding that corporations should pursue policies that advance social welfare at the expense of shareholders. Corporations are not charities and their viability would be jeopardized if they acted like charities. However, retarding social welfare in the interests of shareholders is not appropriate.

This conclusion allows us to offer a general statement of what we believe corporations should strive to achieve: the objective of the firm should be to “maximize” the wealth of corporate shareholders without making any other stakeholders worse off. In other words, they should strive for social welfare improvements (as expanded on below) with shareholders being the primary beneficiaries and other stakeholders either benefitting or, at minimum, being held harmless. Nonetheless, corporate profitability leading to high shareholder returns and social welfare gains can be achieved (albeit not optimized) simultaneously. The next section expands on this conclusion.

Achieving Shareholder Wealth and Social Welfare Simultaneously

Rather than reinvent the wheel, we adopt as premises a number of conclusions drawn from recent contributions to the literature as well as a few assumptions that seem noncontroversial. Many of these premises are derived from the introduction to a recent Special Topic Forum on Management Theory and Social Welfare in the Academy of Management Review that addressed the issue of improving social welfare in the context of profit-seeking corporations (Jones et al., Reference Jones, Donaldson, Freeman, Harrison, Leana, Mahoney and Pearce2016). We aim to modify and expand on this recent treatise on the topic of social welfare in a profit-driven economy in which shareholder returns still persist as a predominant objective. As such, our analysis is built on the following already established foundation:

1) Stakeholder theory, with its fundamental normative principle that the interests of all corporate stakeholders have intrinsic value, is essential to our analysis. Employing stakeholder analysis has the side benefit of obviating a discussion of negative externalities. Those negatively affected by corporate actions are stakeholders (Freeman, Reference Freeman1984) and the negative effects are incorporated into the stakeholder analysis.

2) Social welfare is defined broadly as “the well-being of a society as a whole, encompassing economic, social, physical, and spiritual health” (Jones, et al., Reference Jones, Donaldson, Freeman, Harrison, Leana, Mahoney and Pearce2016: 220). Importantly, stability and justice, in addition to efficiency, are elements of economic welfare (Marti & Scherer, Reference Marti and Scherer2016).

3) “In theory, there is an array of net benefits – benefits less costs for each individual – that is socially optimal” (Jones, et al., Reference Jones, Donaldson, Freeman, Harrison, Leana, Mahoney and Pearce2016: 221). However, the achievement of such an optimum is all but impossible for two reasons: (a) the economic dimensions of this calculus alone are beyond our cognitive capacity, especially in a dynamic economy; and (b) although the non-economic dimensions of social welfare are certainly legitimate concerns, the metrics employed to measure them are incommensurable with each other as well as with economic measures.

4) Therefore, we cannot optimize social welfare, but we can employ a criterion that can be definitively tied to a particular form of welfare improvements. From the welfare economics literature, Pareto improvements – wherein someone is made better off without making anyone else worse off – emerge as a credible standard for assuring that social welfare improves as corporations pursue profits so as to increase shareholder returns. Indeed, the Pareto criterion can be applied to the non-economic facets of social welfare as well as to the economic facets, rendering the incommensurability of measures far less problematic (Jones, et al., Reference Jones, Donaldson, Freeman, Harrison, Leana, Mahoney and Pearce2016). Therefore, one route to unambiguous social welfare improvements for profit seeking corporations is decisions that increase profits without harming any of the firm’s stakeholders.

5) Outcomes for which no stakeholder group is made worse off, however, probably make up a small proportion of corporate decisions. To consider a much more extensive range of corporate policy decisions, we must consider tradeoffs, making sure that social welfare is assured in the process.

6) Kaldor (Reference Kaldor1939) proposed that since tradeoffs, with winners and losers, were often necessary in policy decisions, social welfare could still be improved if it was possible (in theory) for the winners to compensate the losers without exhausting their gains. Jones and colleagues (Reference Jones, Donaldson, Freeman, Harrison, Leana, Mahoney and Pearce2016) point out that, while the Kaldor criterion does indeed meet the utilitarian standard of a net gain in social welfare, it fails any reasonable standard of distributive justice (because no actual compensation is paid) and procedural justice (because the losses are not voluntarily accepted). Nonetheless, this position requires further elaboration, as does a supplement to Kaldor’s position provided by Hicks (Reference Hicks1939).

We now turn to a more detailed analysis of the three options alleged to enhance social welfare – Pareto improvements, Kaldor improvements, and Hicks improvements – including an approach mentioned by Jones and colleagues (Reference Jones, Donaldson, Freeman, Harrison, Leana, Mahoney and Pearce2016) as “an intriguing line of inquiry for future exploration” (Reference Jones, Donaldson, Freeman, Harrison, Leana, Mahoney and Pearce2016: 225) – Kaldor improvements with compensation. In this analysis, we elaborate on two considerations – surplus transfers and “tragedy of the commons” problems – that we believe are essential to understanding the relationship between the corporate quest for profits and social welfare. Based on the following analysis, we propose/defend a new corporate objective that meets important criteria for social welfare improvement.

Social Welfare According to Pareto, Kaldor, and Hicks

Pareto Improvements

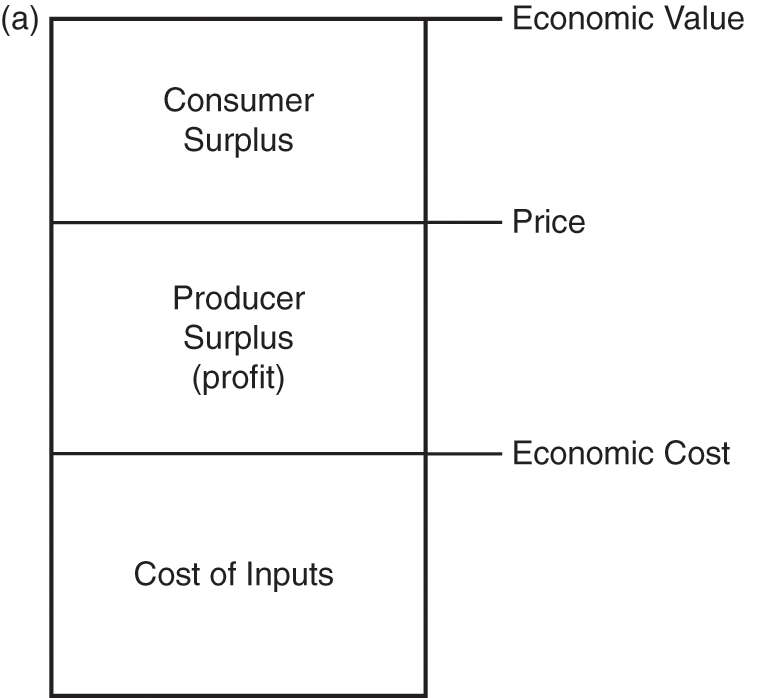

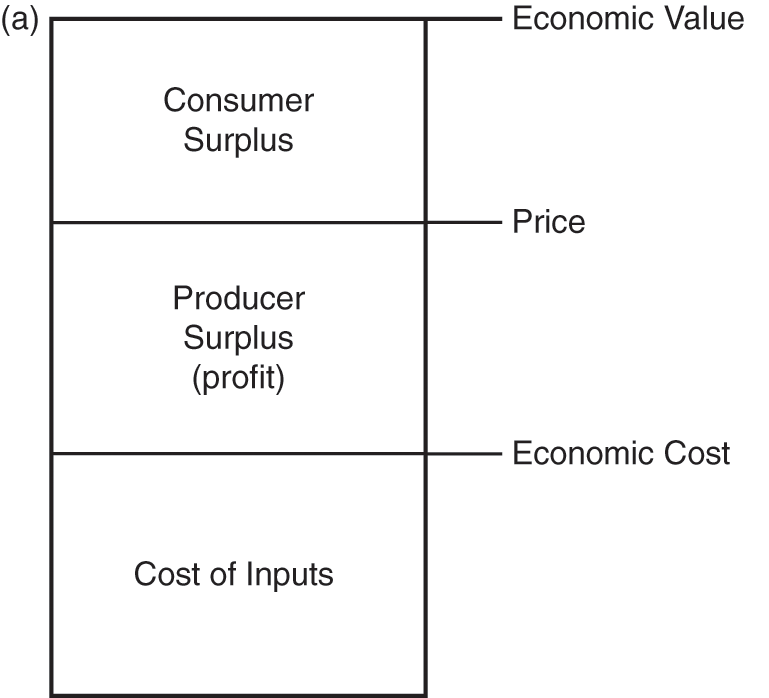

As noted above, the term Pareto improvements applies to exchanges wherein one (or more) parties is (are) made better off without making any other party (parties) worse off. Because one party’s gain does not involve another party’s loss, there is always a net gain, resulting in unambiguous improvements in social welfare. As outlined by Jones and colleagues (Reference Jones, Donaldson, Freeman, Harrison, Leana, Mahoney and Pearce2016), and with reference to Figure 5.1a, firms have three ways of increasing profits. They can: (1) increase/reduce price while holding economic value and input costs constant; (2) increase economic value and price while holding input costs constant; or (3) reduce input costs while holding economic value and prices constant.8

Surplus Transfers

Under condition set 1, although the price/quantity relationship of its product may allow a firm to increase its profits either by increasing or decreasing its prices, price increases will result only in surplus transfers (Shleifer & Summers, Reference Shleifer and Summers1990), thus apparently failing the Pareto test.9 Under condition set 2, raising prices more than the incremental economic value added also results only in surplus transfers from customers to the producer, another apparent failure of the Pareto test. Under condition set 3, if the firm, using market power made possible by disequilibrium conditions, forces price reductions on its suppliers or appropriates more than the incremental surplus generated by production efficiencies or transaction costs efficiencies, it will only be transferring surplus value from its suppliers to itself, another apparent Pareto test failure. If, however, firms avoid these practices in their quest for greater profits, the Pareto criterion for social welfare will be met. In other words, increasing profits to benefit shareholders and enhancing social welfare simultaneously is a highly contingent enterprise: how a firm generates additional profits matters a great deal with respect to enhancing social welfare.

A few examples of Pareto improvements should help illustrate our points. Firms that develop new products/services or improve existing products/services and appropriate no more than the incremental surplus meet the Pareto improvement standard. In addition, Priem (Reference Priem2007) highlights ways that firms can grow the “top line.” As long as the firm raises prices no more than the incremental value added, social welfare will be improved. Pareto improvements can also be achieved by firms with market power reducing their prices, as described above, thus increasing the consumer surplus of existing customers and adding new customers. Assuming that the price reduction actually improves the firm’s profits, Pareto improvements accrue. Similarly, reductions in input costs that result from transaction costs efficiencies can result in Pareto improvements as long as the focal firm does not appropriate more than the savings created. Because Pareto improvements unambiguously enhance social welfare, they are a desirable element in our modified corporate objective.

Kaldor Improvements

Since Pareto improvements are unlikely to be possible over a large range of potential corporate decisions, we must consider situations in which cost/benefit tradeoffs are required. If the “winners” can (in theory) compensate the “losers” for their losses and remain “winners,” a Kaldor improvement in social welfare can be made. In the preceding discussion, we were careful to use the term surplus rather than wealth and add the adjective apparent because, as we consider Kaldor improvements, the choice of wording is important and substantial. Surpluses transferred between non-shareholder stakeholders are transferred on a roughly one-to-one basis. A price concession extracted from a supplier and passed in its entirety on to customers in the form of reduced prices results in no net change in total surpluses. However, when producer surpluses are involved in the transfer, those surpluses are translated into shareholder wealth at a rate roughly equal to the price/earnings ratio that the firm’s stock commands on the stock market. Using the very conservative 10–1 ratio suggested by Jones and colleagues (Reference Jones, Donaldson, Freeman, Harrison, Leana, Mahoney and Pearce2016), $1 of surplus transferred from, say, employees to the producer (the firm) results in a roughly $10 increase in shareholder wealth.10 Thus, a firm that shifts $1 million of health care costs from the company to its employees could expect to realize roughly $10 million in increased market value. Therefore, in many cases, surplus transfers from non-shareholder stakeholders do indeed increase aggregate wealth, a Kaldor improvement in social (economic) welfare, at least in the short run.

In spite of the apparent improvements in aggregate welfare from Kaldor improvements, the actual wealth reduction for employees will probably extend beyond one year and the actual aggregate wealth created over the longer term will be a function of not only the expected duration of the benefit reduction, but also the P/E ratio of the firm. For companies with low P/E ratios, the wealth lost by employees could exceed the wealth gained by shareholders in a few years, resulting in an aggregate wealth reduction and a violation of our rule that aggregate wealth should never be destroyed. Thus, social welfare improvements resulting from corporate profit seeking, while virtually certain in the short run, are highly contingent over longer time periods. Another threat to longer-term social welfare enhancement is discussed in detail below.

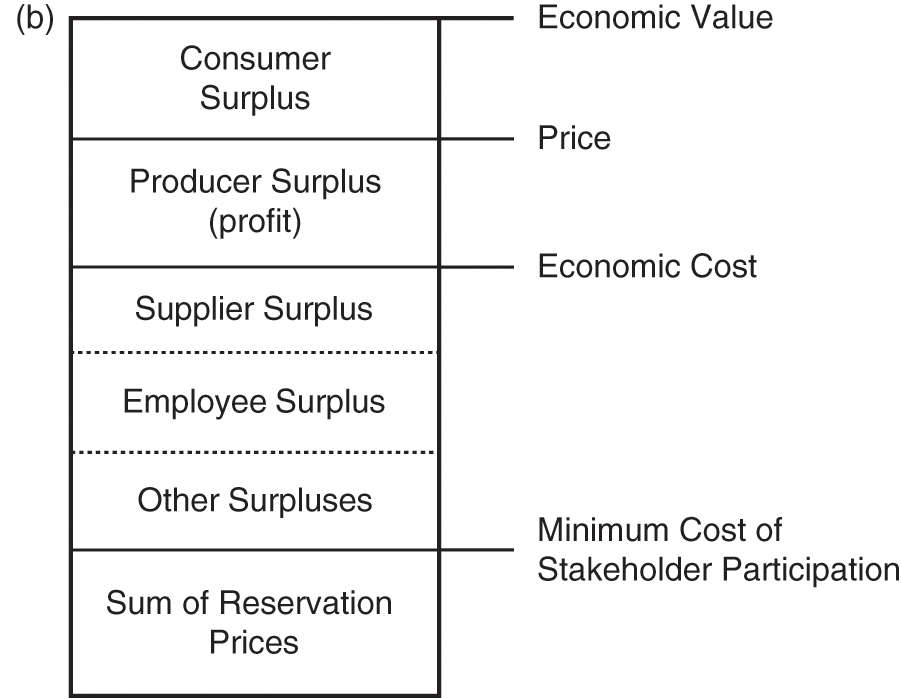

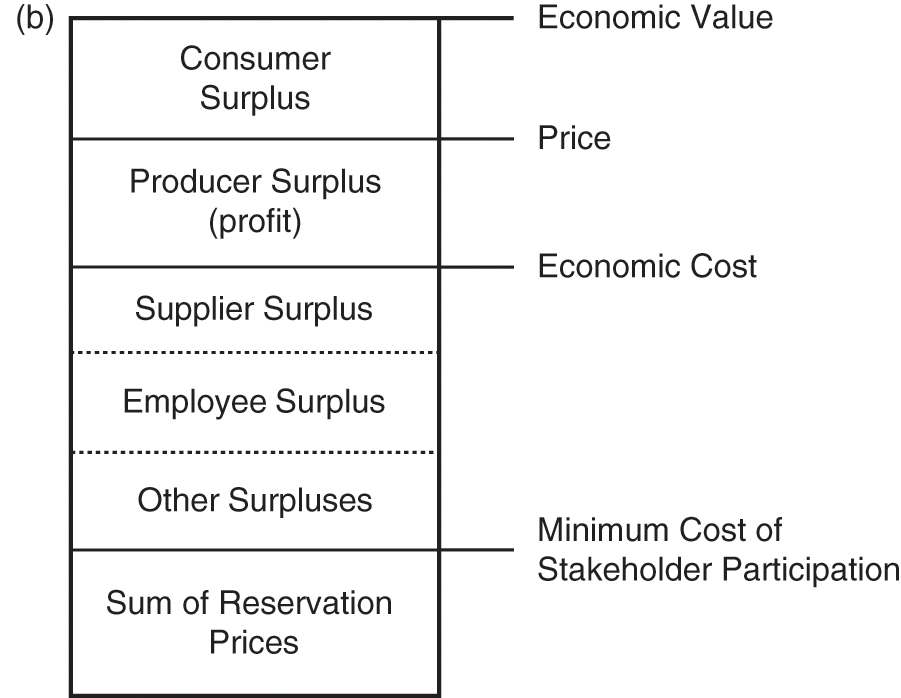

It appears that, through applications of the aggregate wealth creation criterion in the short run, corporations would be justified in cutting (ideally minimizing) their costs in any number of ways – e.g., eliminating not only “extraneous” employees, but also the benefits of remaining employees (vacations, retirement plans, sick leave, day care services, subsidized cafeterias, and health care insurance, etc.) as well as cutting wages until employee attrition becomes too costly. Cost savings involving other stakeholders could result in cutting supplier prices to the bone, reducing customer service as far as market forces would allow, forcing local governments to reduce taxes under threat of moving to another locale, eliminating community involvement programs, and so on. In other words, a corporate objective of shareholder wealth maximization could be justified, in Kaldor improvement terms, to force payments to these stakeholders down to their reservation prices (see Figure 5.1b).11 In aggregate economic welfare terms, policies that convert non-shareholder stakeholder wealth to shareholder wealth would almost always result in net welfare gains in the short run – gains to shareholders routinely exceeding losses to other stakeholders – thereby meeting a utilitarian (aggregate social welfare) ethical standard as well.

Under this decision criterion, aggregate economic wealth would certainly be increased in the short run, but with non-shareholder stakeholders consistently sacrificing wealth in favor of (greater) wealth for shareholders, the economic sustainability of the system as a whole is called into question. At the firm level, Ghemawat and Costa (Reference Ghemawat and Costa1993) make a similar distinction between static efficiency and dynamic efficiency, where static efficiency refers to earning the greatest profit possible in the short term, while dynamic efficiency involves positioning the firm to produce and sell competitive products/services into the foreseeable future.

In addition, while the wealth transfers associated with the pursuit of profit maximization could increase (static) efficiency – i.e., Kaldor improvements – in the economy very substantially, they would fail our expanded Pareto test because of substantial increases in income/wealth inequality – i.e., a setback for distributive justice. Of course, the coercive aspects of transfers of this type would remain.

In fact, the economic history of the USA over many years is highly consistent with an analysis based on Kaldor improvements. Aggregate income and wealth seem to grow at consistent, if not always spectacular, rates even as income and wealth grow ever-more concentrated in the hands of a small proportion of the population. Simply put, the country keeps getting collectively richer, but also more and more unequal (Piketty, Reference Piketty2013). Furthermore, if this means of improving aggregate social welfare continues into the future, the USA could see income/wealth disparities even greater than those currently observed. However, as we argue in the next section, a regime of Kaldor improvements could present an even greater threat in the long term.

A “Tragedy of the Commons” Economy?

Originally associated with the grazing of cattle on commonly owned pastures, the “tragedy of the commons” has come to represent situations in which firms, acting rationally in their self-interest, can severely deplete resources held in common, sometimes to the point of economic ruin for firms in a particular market.12 The frequently used example of fishing grounds makes this point quite clear. For a given fishery, the best way for an individual boat owner to maximize his/her profits is to maximize his/her catch; catching as many fish as possible in the shortest possible time maximizes the profits of the individual boat. For the fishery as a whole, however, this strategy, if employed by all boats, can lead to disaster. Left unchecked, this strategy will deplete the stock of fish, perhaps totally, and all boats will be out of business. Even if some boats drop out of the market, the incentives will remain the same for the remaining boats. Furthermore, when the price of fish rises with declining catches, the incentive to catch more fish merely grows larger. Examples on a larger scale include environmental pollution and global climate change. In all cases of the tragedy of the commons, the pursuit of maximum profits by individual firms creates wealth and expands social welfare only in the short term. How does this parable apply to social welfare under a regime of Kaldor improvements?

Applying the Kaldor criterion, corporations create greater net wealth by increasing shareholder wealth – i.e., rising share prices – at the expense of the wealth of other stakeholders. Absent other changes, non-shareholder stakeholders would become less and less prosperous.13 While an increasing concentration of wealth is normally not a concern in a utilitarian (aggregate social welfare) moral logic, it can become a significant concern over the long term due to a dynamic analogous to the tragedy of the commons.

This analogy makes sense if one thinks of the consuming (buying) power of the population as “the commons.” That is, the ability and willingness of people to consume the output of economic producers is a resource available to all producers and, like many resources, it can be depleted and, in extreme cases, nearly destroyed. Importantly, this consuming power is essential to the perpetuation of a healthy market economy since about 70 percent of the US gross domestic product is consumer spending. To be sure, those becoming increasingly wealthy are also consumers, but they invest a far greater proportion of their income/wealth than do those less well off. And, of course, the wealthy make up a small proportion of the total population.

The “tragedy” is that individual firms, acting in an economically rational manner – i.e., maximizing profits – will implement decisions that marginally diminish the buying power of large segments of the population. If the wealth of non-shareholder stakeholders is regularly being transferred to shareholders, these stakeholders, as consumers, become less able to purchase the output of the corporate sector. If employees earn less, pay for their own insurance, pensions, and other benefits, and become less numerous; if suppliers operate increasingly marginal businesses (and, presumably, drive down the wages paid to their employees and prices paid to their suppliers); if customers pay higher prices and experience reduced customer service; if local governments increasingly are unable to provide and maintain infrastructure (as firms are given tax breaks); and if companies become increasingly separated from the communities in which they operate, then the continuing pursuit of shareholder prosperity is likely to be unsustainable. Collectively, there is a potential for shrinking markets for many products and a downward spiral in the economy as a whole. In other words, a tragedy of the commons economy could emerge.14 In short, an ongoing quest for Kaldor improvements as the criterion for enhanced social welfare could be disastrous for social welfare in the longer term.15

Kant’s Universalizability Criterion

Although our analysis thus far has been couched in terms of social welfare (i.e., a utilitarian approach), which stresses an optimal balance of favorable and unfavorable consequences, we recognize that elements of deontological ethics are relevant as well. According to the deontological perspective, certain moral principles are morally binding regardless of the consequences that may result. More specifically, Kant’s notion of universalizability comes into play. Universalizability means that, in order for a principle to be morally binding, it must be acceptable for everyone to adopt it; in simpler terms, no one should be able to play by their own moral rules. A classic application of universalizability involves promises. Although it sometimes becomes expedient for an agent to renege on a promise, the moral acceptability of doing so rests on whether reneging on promises would be acceptable for everyone who could benefit from doing so. However, if everyone were to regard the commitments that underlie promises as binding only if honoring them were in the promisor’s interests, the concept of promises would cease to have any meaning and their value in human interactions would be virtually nil.

With respect to our “tragedy of the commons economy” analogy, universalizability applies when an individual firm marginally reduces the consuming power of the populace by transferring wealth from non-shareholder stakeholders to shareholders by, for example, cutting health care benefits to employees or extracting price concessions from suppliers. In our example, total wealth almost certainly increases in the short run because shareholder wealth increases at (about) 10 times the rate that stakeholder wealth (surplus) decreases. However, if it were morally acceptable for all firms to transfer wealth from non-shareholder stakeholders to shareholders, theoretically reaching the reservation prices of stakeholders, the consuming power of the economy as a whole would collapse – a “tragedy of the commons” outcome. Thus, although wealth transfers from non-shareholder stakeholders to shareholders are acceptable under the Kaldor improvement criterion, they would be prohibited under Kant’s universalizability criterion.

Regardless of the perspective one takes, an economy operating under criteria that allow profit maximizing wealth transfers from non-shareholder stakeholders to shareholders could lead to a near-Hobbesian world in which life for many people could be “solitary, poore, nasty, brutish, and short.” On the other hand, an economy populated with firms: (1) striving for dynamic efficiency; (2) trying to avoid an economic tragedy of the commons; and (3) concerned about the universalizability of their actions, should be able to maintain a high level of economic/social welfare, the ultimate end of economic systems founded on utilitarian principles.

Although negative externalities are largely subsumed under “harms to non-shareholder stakeholders” in our analysis, the use of some common resources is inevitable in most economic activities. Given this situation, we note that many “tragedy of the commons” problems cannot be solved by individual firms; they almost always require allocation decisions made by political entities. Under such circumstances, firms can make Pareto or Kaldor improvements by drawing on the common resource – e.g., fishing grounds, acceptably clean air or water, the earth’s ability to dissipate heat – only to the extent permitted by public policy.

The apparent magnitude of the efficiency gains through applications of the Kaldor criterion for social welfare enhancement suggest not only a major problem with profit seeking by corporations under these conditions, as discussed in the previous section, but also a plausible solution. We now address this possible solution.

Hicks Improvements

Jones and colleagues (Reference Jones, Donaldson, Freeman, Harrison, Leana, Mahoney and Pearce2016) mention an addendum to Kaldor’s insight by Hicks (Reference Hicks1939) – in situations requiring tradeoffs, social welfare gains can also be assured if the potential losers could (in theory) pay the focal decision-maker not to proceed with the proposed action. However, as in the case of Kaldor improvements, no actual payments were contemplated, so the distributive aspects of the Hicks addendum are clearly negative. Potential losers are still losers and, even though net social welfare in efficiency terms may be improved, our expanded Pareto criterion is not met. Efficiency is enhanced at the expense of distributive justice. Also, the coercion of losers violates our sense of procedural justice. Indeed, given the relationship between shareholder wealth increases and non-shareholder stakeholder surplus decreases, the Hicks criterion becomes absurd. Shareholders would (in theory) demand payments based on the potential increase in the value of their stock at our assumed 10 to 1 ratio to the potential losses of non-shareholder stakeholders, such payments would be irrational in the extreme, not to mention unaffordable to many of these potential “losers.” Thus, any application of the Hicks addendum in the context of shareholder/non-shareholder stakeholder tradeoffs is a nonstarter, regardless of whether it would lead to greater aggregate economic wealth.

A Modified Corporate Objective

Given the analysis of the preceding sections, the central question becomes: what corporate objective would best serve to enhance social welfare? Recall that we are asking our version of IST to be instrumental in two ways. We seek to find ethically appropriate means of: (1) helping firms achieve improved profitability so as to provide high shareholder returns; and (2) simultaneously enhance social welfare through their economic activities. In other words, we seek means of achieving sustainable wealth creation. We premise our discussion of alternative corporate objectives on three fundamental principles. First, aggregate wealth must never be destroyed in the “wealth creation” process; profit should not be pursued in cases where social/economic welfare, including effects on all corporate stakeholders, is reduced. Second, the baseline condition for comparison purposes must be the set of existing entitlements of current normatively legitimate stakeholders of the firm.16 While this principle is bound to be controversial, we know of no other way to avoid advocating a truly massive and disruptive (and hence unrealistic) redistribution of wealth in society.17 These existing entitlements include jobs, employee benefits, contracts with suppliers and customers, debt covenants, commitments to communities, etc. Third, the profit motive must be retained. The economic incentive provided to those who seek to gain from the creation of new wealth should not be replaced.

These three premises suggest that an appropriate corporate objective is that the firm should increase the wealth of its shareholders without reducing (and presumably increasing) the aggregate wealth of its other stakeholder groups. One means of achieving this objective is through seeking improved profitability by making Pareto improvements, an approach examined in adequate detail in the previous section. In addition, based on the previous analysis, we reject the conclusion that companies should always make profit-enhancing tradeoffs because they enhance economic welfare in the short run. Instead, we argue that firms should do so only if they actually compensate stakeholders for their losses.

Kaldor Improvements with Compensation

Based on the discussion in the previous section, we propose that actual compensation be paid to stakeholders harmed by policies intended to increase shareholder wealth, a position we call Kaldor improvements with compensation. Actual compensation would assure that wealth is not destroyed in the “wealth creation” process. If those harmed by corporate policies are actually compensated for their losses – i.e., “made whole” – and if profits increase anyway, we can be assured that utilitarian (social/economic welfare) ends are served.

Given the substantial difference between shareholder gains ($10 million, in our example) and the annual losses of other stakeholders ($1 million), it would seem an easy task to compensate stakeholders for their losses. However, although firms have some control over decisions regarding the allocation of surpluses between the company (producer surplus) and, for example, employees (employee surplus), once improved earnings are reported, the gains are no longer within the control of company executives; that is, share values may have increased, but the shares belong to the shareholders. What can be done?

One solution is to compensate stakeholders who are harmed by shareholder wealth maximizing policies with company stock to mitigate their losses. In theory, these stakeholders should be given stock equivalent to their losses, but since these losses often cannot easily be determined, we use the term mitigate. However, with P/E ratios historically around 15 and currently around 25, firms should have the resources – in shareholder equity – to substantially ease the pain of stakeholder losses. To extend our example, employees who, in total, suffered annual losses of $1 million in company-paid insurance premiums could be given company stock with a value equivalent to a year or two of their losses without seriously undermining the gains of shareholders.18 In other words, those harmed by wealth tradeoffs made at a ratio of 1/1 (producer surplus/employee surplus) could be compensated for their losses at a wealth ratio of 10/1 (in our example), resulting in a net gain in social/economic welfare and, by extension, a policy acceptable by utilitarian (Pareto or Kaldor) standards.

To be sure, the aggregate value of shareholder wealth increases would be diluted by the number of shares given to employees in compensation for their losses and, in some cases, additional shares would have to be issued, but the effects of this dilution would, in most cases, be modest in comparison to share price gains. In other words, shareholders would be required to give up some gains made at the expense of other stakeholders, but the amounts they would be required to give up are subject to the share price/employee surplus ratio (10/1) rather than the producer surplus/employee surplus ratio (1/1). In this way, shareholder wealth can be increased without harming other stakeholders, in accordance with the standards of Pareto improvements in social welfare. Furthermore, because the tragedy of the commons can be mitigated in this way, the application of Kaldor improvements with compensation paid in company stock to stakeholders harmed by profit-enhancing corporate actions will allow the resulting wealth creation to be much more sustainable.

The Social Welfare Proposal Summarized

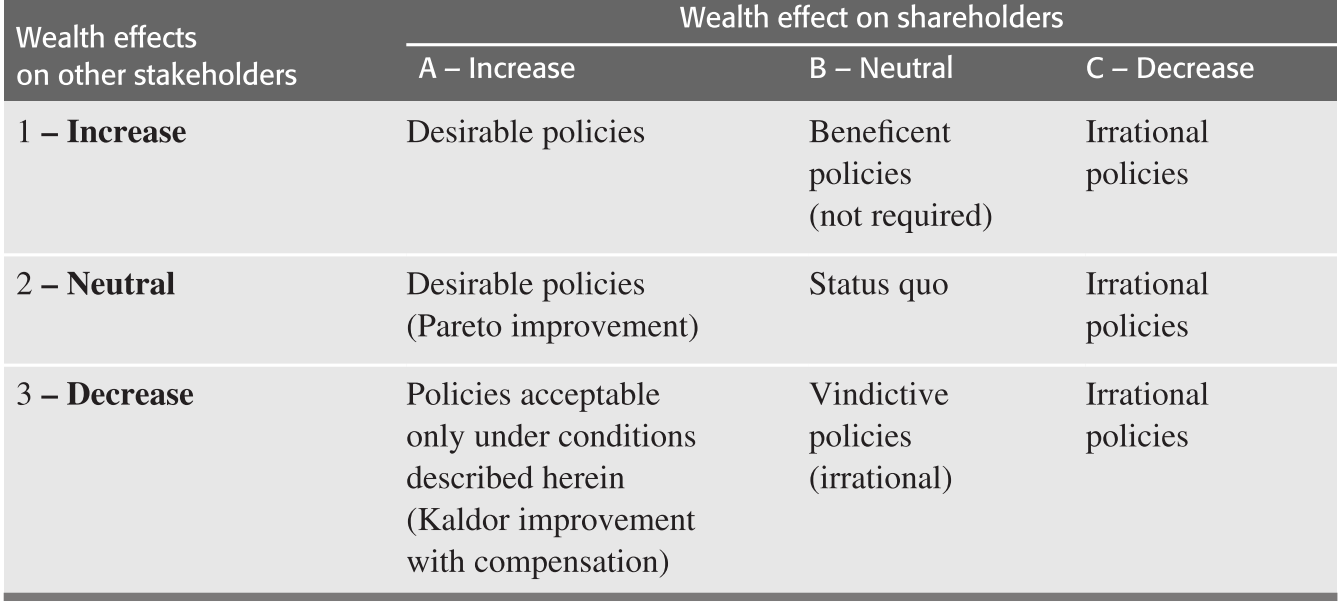

A detailed summary of the Pareto Improvements, Kaldor Improvements, and Kaldor Improvements with Compensation decision criteria is presented in Table 5.1.

| Wealth effects on other stakeholders | Wealth effect on shareholders | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| A – Increase | B – Neutral | C – Decrease | |

| 1 – Increase | Desirable policies | Beneficent | Irrational |

| policies | policies | ||

| (not required) | |||

| 2 – Neutral | Desirable policies | Status quo | Irrational |

| (Pareto improvement) | policies | ||

| 3 – Decrease | Policies acceptable | Vindictive | Irrational |

| only under conditions | policies | policies | |

| described herein | (irrational) | ||

| (Kaldor improvement | |||

| with compensation) | |||

Table 5.1 clarifies the meaning of our stated corporate objective in more specific terms. First, policies that cause shareholder wealth to decline (Column C) are never appropriate, regardless of their effect on aggregate economic welfare. The quest for profits motivates corporate behavior and we see no reason to advocate financially irrational policies, especially since they fail the Pareto improvement criterion. Nor do we advocate corporate engagement in “socially responsible” practices that are purely altruistic (Cell C1) since they fail not only the Pareto criterion but, assuming P/E ratios greater than 1, the Kaldor test as well. Second, policies with no effect on shareholder wealth (Column B) are never required, but could be adopted in the interest of beneficence, the moral principle that commends acts that benefit others at no (or little) cost to the agent. Finally, and most relevant to our analysis, policies that increase shareholder wealth (Column A) are desirable/acceptable according to more detailed criteria.

Cell 1 A represents ideal policies, those likely to elicit little argument. Shareholder wealth, as well as the wealth of other stakeholders, is increased. Cell 2 A also represents desirable policies, those that enhance shareholder wealth without decreasing the wealth of other stakeholders. These policies meet the Pareto criterion and have clear positive economic welfare implications. Cell 3 A represents situations in which shareholder wealth is increased at the expense of other stakeholders and are described above under “Kaldor Improvements with Compensation.” As long as corporate actions/policies meet one of the requirements of Column A (or B1), social welfare will rise as corporations seek increased profits.

Institutional Accommodations

Although the adoption of a sustainable wealth creation standard for managers would involve some significant changes in the way that corporations are governed, there seem to be few formal institutional barriers to the changes that we propose. First, as Stout (Reference Stout2012) and others have made abundantly clear, the existing law of corporations could accommodate such changes. Although corporate directors owe duties of loyalty and care to the corporation, nothing requires them to regard maximizing the wealth of shareholders as their only responsibility. Indeed, the business judgment rule, wherein courts defer to the judgment of those with expertise in business, grants corporate boards a great deal of latitude in terms of what they consider to be the best interests of the firm. Stout sums up her analysis by stating that “American corporate law […] fiercely protects directors’ power to sacrifice shareholder value in the pursuit of other corporate goals” (Reference Stout2012: 32). Nonetheless, because appropriate business judgment is determined by courts, the resulting uncertainty causes many boards to err on the side of shareholder interests to avoid litigation (Cormac & Haney, Reference Cormac and Haney2012). In addition, the pressure from financial markets to produce impressive quarterly returns keeps profitability front and center in the minds of corporate managers and directors (Cormac & Haney, Reference Cormac and Haney2012; Reiser, Reference Reiser2011).

Another legal mechanism that could potentially serve to support sustainable wealth creation is the existence of other constituency or stakeholder statutes in several states. These laws, which allow, but do not require, corporate managers and directors to take the interests of non-shareholder stakeholders into account in their deliberations, are now on the books in a majority of states. On the surface, these statutes seem to acknowledge the legitimacy of stakeholder interests in corporate decision-making. However, a closer look reveals another motive. Most of these statutes were passed in the midst of a wave of takeover attempts – actual and threatened – that would involve substantial layoffs of employees of target firms. The new statutes allowed corporate officers to actively resist such takeovers, which would clearly benefit shareholders, under the banner of protecting employee interests. While deterring the layoff of local jobholders is certainly a noble goal, the protection provided for incumbent managers, who would presumably be replaced after a takeover, cannot be ignored. Indeed, a number of states specifically allow the consideration of stakeholder interests only in the event of a potential “change of control,” strongly suggesting that the second motive dominated the first in the passage of many stakeholder statutes. Reiser has gone so far as to call these statutes “anti-takeover legislation” (Reference Reiser2011: 599). Regardless of their intent, stakeholder laws clearly give corporate managers and directors additional latitude with respect to their pursuit of values other than shareholder wealth maximization.

Nonetheless, public policy makers seem to have anticipated changes of the general nature of our proposal in the very recent past. More specifically, several states, beginning with Maryland in 2010, have passed benefit corporation statutes that, in addition to generating profit for shareholders, require firms to provide a general benefit to society (Reiser, Reference Reiser2011). Although statutory provisions vary from state to state, they have some common features that would facilitate the establishment of firms devoted to sustainable wealth creation. First, dual missions are required. Firms must provide a material, positive benefit (general or specific) for society along with profits for shareholders. Second, they impose fiduciary duties on directors to include the interests of non-shareholder stakeholders, in addition to those of shareholders, in their decision-making processes.19 Third, they stress accountability by requiring reporting of the firm’s social and/or environmental performance to an independent third party.

Benefit corporation statutes also eliminate the threat of lawsuits based on conventional, single-purpose views of the corporate objective – i.e., profit maximization. Therefore, benefit corporations should be able to pursue their social missions without the institutional restrictions that inspire other firms to focus exclusively on the bottom line. In addition, the formal designation “benefit corporation” should allow firms that truly have a social mission to distinguish themselves from conventionally chartered firms that wrap themselves in the cloak of social or environmental responsibility even as they continue their exclusive pursuit of profit. Put differently, the designation “benefit corporation” should help interested parties – customers, employees, etc. – to separate rhetoric from reality (Reiser, Reference Reiser2011). To sum up, while this part of our chapter attempts to create a compelling normative case for sustainable wealth creation, a growing number of states have created institutional mechanisms through which this form of wealth creation could gain a practical foothold.

An Agenda for Future Research

A proposal as broad and as foundational as the one presented here necessarily leaves a significant number of questions unanswered and, as a result, leaves the underlying normative theory vulnerable to claims that it is underdeveloped. However, it would be counterproductive to judge a new normative theory negatively because it fails to meet the standards of development and refinement set by a theory that has been subjected to over 230 years of scrutiny, development, and refinement – i.e., since Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations (Reference Smith1776) – and still leaves some questions unanswered – e.g., unequal distributions of income and wealth; externalities. Therefore, in the interest of beginning a scholarly discussion of these issues, we offer a short list of general questions to start the conversation.

1) If stakeholders harmed by shareholder wealth-enhancing corporate actions are to be compensated, a definitive list of eligible stakeholders will need to be established. For example, should governmental units be compensated for lost tax revenues when terminated employees are no longer paying taxes? A discussion of this issue could begin with the definition of normatively legitimate stakeholders articulated by Phillips (Reference Phillips2003).

2) If stakeholders harmed by profit-enhancing corporate actions are to be compensated for their losses in corporate shares, how much stock should they receive? In the case of terminated employees, shares worth a lifetime’s wages would clearly be too much, while shares equivalent to a two-week severance package would be too little. Key considerations in such a calculation would involve fairness, perhaps based on years of service, the market for the employees’ services, incentives to return to the workforce sooner rather than later, and the effect on the consuming/buying power of the economy as a whole.

3) How should stakeholders whose wealth per se is not reduced but whose well-being is harmed – e.g., surviving employees who have to absorb the work of their terminated former co-workers – be compensated?

4) How are critical lines to be drawn between situations that warrant compensation and those that do not? For example, sometimes the survival of a firm will depend on the layoff of a significant number of employees while at other times a layoff of similar magnitude will be undertaken simply to make the firm “lean and mean.” In the former case, compensation would make little sense while in the latter case it would. But, given that there will be cases in between these two extremes, where should the line be drawn?

We have no illusions about the difficulties involved in answering these and related questions. However, human beings and the institutions that surround them are capable of substantially improving the quality of their decisions, even those with no clear guidelines, over time. In particular, we have faith in the ability of talented managers and scholars to come up with increasingly workable solutions given appropriate incentives to do so. The alternative is to continue to allow the harms done in the pursuit of corporate profits to be borne entirely by non-shareholder stakeholders, with all the negative distributive effects associated with that outcome, and to risk the emergence of a “tragedy of the commons” situation within the economy as a whole.

Summary and Conclusions

This chapter began with a brief examination of, and empirical support for, IST as originally envisioned. We found that there is strong reason to believe that companies that practice management based on IST principles, on average, can also enhance their profit performance, thus satisfying the widely accepted notion that enhancing profit performance to increase shareholder returns is one of the most important (some would say the most important) objectives of a corporate manager. We then enlarged the discussion to consider the domain of social welfare in general, arguing that there is an important point of tension between objectives within modern market capitalism, and that management scholars should recognize it and address it in a direct way. One objective – corporate profit maximization to increase shareholder returns – is not always compatible with the other – wealth creation at the societal level – a foundational objective of economic activity in general. The continuing quest by strategy scholars to identify practices that result in sustainable competitive advantage so as to maximize shareholder returns will sometimes, but not always, result in social welfare increases. Scholars who engage in sustainable competitive advantage research should also assess the sustainability of the practice in question for the economy as a whole if all firms engaged in similar practices. The goal of integrating social welfare concerns into our research agendas was advocated by Walsh, et al. (Reference Walsh, Weber and Margolis2003) over a decade ago. These authors, after providing evidence that “performance and welfare work at the societal level of analysis seems to be the least appreciated work of all” in the management literature, suggest that it is time to “rekindle the debate about the purposes of the firm and about the place of the corporation in society” (862; 877).

Unfortunately, a distressingly large number of corporate managers seem to pursue greater corporate financial performance without regard for harm done to stakeholders other than shareholders. This chapter is also a call for strategy scholars to engage in research that carefully discriminates between corporate policies that result in actual wealth creation and those that result only in wealth transfers, encouraging managers to avoid the latter unless the losses of non-shareholder stakeholders are appropriately compensated. The development of methods of determining appropriate compensation for such losses should also be on the agenda. The proposed changes in the corporate objective represent the direct creation of economic wealth with respect to discrete decisions, as advocated by Quinn and Jones (Reference Jones1995), rather than reliance on the assumption that increasing the wealth of shareholders alone will unerringly enhance social/economic welfare over time.

To some extent, the two strategy research agendas – traditional and proposed – will overlap; there are certainly shareholder wealth enhancing policies that do not harm, and may help, other stakeholders (e.g., Jones, et al., Reference Jones, Harrison and Felps2018). Indeed, as demonstrated by the research examined in the first section of this paper, there is substantial evidence that firms that manage for stakeholders also have high profits leading to increased shareholder wealth. However, there are several categories of policies that result in gains for shareholders but also losses for other stakeholders, and we must be assured that the losses incurred by these other stakeholders are substantially mitigated in order to keep the economy sustainable. Managers should also be attuned to this new agenda. If they take the broad wealth creation charter of business seriously, they must take the wealth of all their stakeholders into account.