Book contents

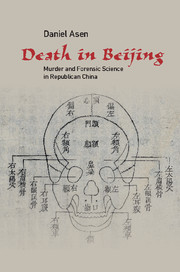

- Death in Beijing

- Science in History

- Death in Beijing

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Figures

- Book part

- Introduction

- 1 Suspicious Deaths and City Life in Republican Beijing

- 2 On the Case with the Beijing Procuracy

- 3 Disputed Forensics and Skeletal Remains

- 4 Publicity, Professionals, and the Cause of Forensic Reform

- 5 Professional Politics of a Crime Scene

- 6 Dissection and Its Discontents

- 7 Legal Medicine during the Nanjing Decade

- Conclusion: A History of Forensic Modernity

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 July 2016

- Death in Beijing

- Science in History

- Death in Beijing

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Figures

- Book part

- Introduction

- 1 Suspicious Deaths and City Life in Republican Beijing

- 2 On the Case with the Beijing Procuracy

- 3 Disputed Forensics and Skeletal Remains

- 4 Publicity, Professionals, and the Cause of Forensic Reform

- 5 Professional Politics of a Crime Scene

- 6 Dissection and Its Discontents

- 7 Legal Medicine during the Nanjing Decade

- Conclusion: A History of Forensic Modernity

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Death in BeijingMurder and Forensic Science in Republican China, pp. 233 - 250Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2016