Book contents

- English Alliterative Verse

- Cambridge Studies in Medieval Literature

- English Alliterative Verse

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures

- Acknowledgments

- Abbreviations

- Evolution of the Alliterative B-Verse, 650–1550

- Introduction: The Durable Alliterative Tradition

- Chapter 1 Beowulf and Verse History

- Chapter 2 Prologues to Old English Poetry

- Chapter 3 Lawman, the Last Old English Poet and the First Middle English Poet

- Chapter 4 Prologues to Middle English Alliterative Poetry

- Chapter 5 The Erkenwald Poet’s Sense of History

- Chapter 6 The Alliterative Tradition in the Sixteenth Century

- Conclusion: Whose Tradition?

- Note to the Appendices

- Book part

- Glossary of Technical Terms

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

- Cambridge Studies in Medieval Literature

- References

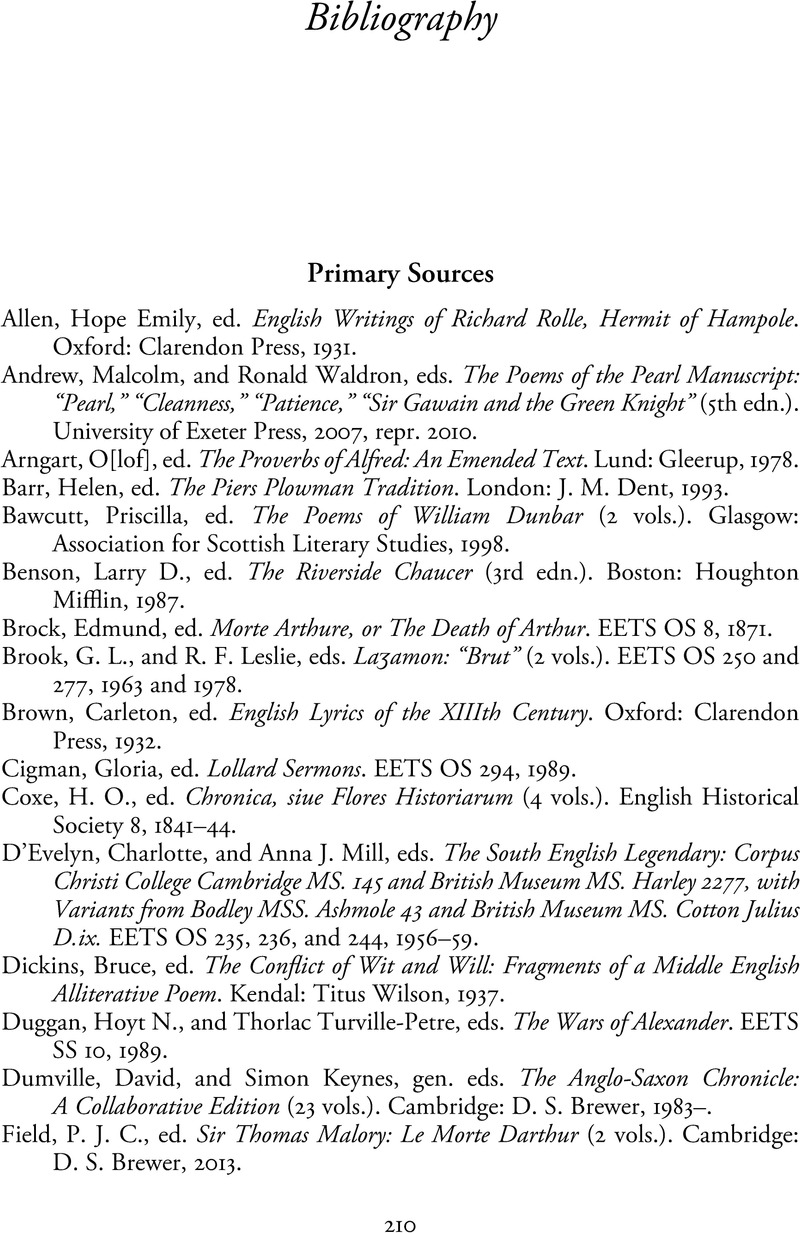

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 09 November 2016

- English Alliterative Verse

- Cambridge Studies in Medieval Literature

- English Alliterative Verse

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures

- Acknowledgments

- Abbreviations

- Evolution of the Alliterative B-Verse, 650–1550

- Introduction: The Durable Alliterative Tradition

- Chapter 1 Beowulf and Verse History

- Chapter 2 Prologues to Old English Poetry

- Chapter 3 Lawman, the Last Old English Poet and the First Middle English Poet

- Chapter 4 Prologues to Middle English Alliterative Poetry

- Chapter 5 The Erkenwald Poet’s Sense of History

- Chapter 6 The Alliterative Tradition in the Sixteenth Century

- Conclusion: Whose Tradition?

- Note to the Appendices

- Book part

- Glossary of Technical Terms

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

- Cambridge Studies in Medieval Literature

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- English Alliterative VersePoetic Tradition and Literary History, pp. 210 - 227Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2016