1.1 Introduction

In the 1970s, unprecedented peacetime inflation, touched off by the oil cartel OPEC, combined with long-standing federal tax privileges to transform owner-occupied homes into growth stocks in the eyes of their owners. The inability to insure their homes’ newfound value converted homeowners into “homevoters,” whose local political behavior focused on preventing development that might hinder the rise in their home values. Homevoters seized on the nascent national environmental movement, epitomized by Earth Day, and modified its agenda to serve local demands. The coalition of homeowners and environmentalists thereby eroded the power of the pro-development coalition called the “growth machine,” which had formerly moderated zoning. As this chapter shows, these changes in the meaning of homeownership and in the political behavior of homeowners explain why local zoning has become so restrictive.

Zoning is not a new institution. Housing in the United States has been the subject of comprehensive local government regulation since 1916, when New York adopted the nation’s first zoning laws. Zoning spread rapidly to other cities, and now almost all cities and towns in urban areas have zoning and a host of related land use regulations (Fischel Reference Fischel2015). It is now well established that in certain areas of the nation – the Northeast and West Coast especially – local land use regulation is associated with unusually high housing prices. The excessive housing prices retard mobility of labor, reduce national productivity, and worsen income inequality (Ganong and Shoag Reference Ganong and Shoag2013). Some have also argued that the inelastic supply of housing contributed to the 2000s housing bubble and the financial crisis that resulted when it burst (Jansen and Mills Reference Jansen and Mills2013).

This chapter seeks to establish that the restrictive zoning policies that contributed to the housing crisis arose at a particular time – the 1970s – in conjunction with worldwide inflation and American political movements that undermined the transactional relationship between local governments and developers. Evidence presented here establishes that the 1970s represented a sharp break with the past. It is important to understand both the history and probable causes of growth controls in order to shape reasonable responses to excessive land use regulation.

My empirical contribution in this chapter is something called Ngrams. Not shown are some other trends that are important but hardly novel. The first is that the time trend of real housing prices (that is, adjusted for inflation) in the post–World War II era was flat or gradually falling up to about 1970 (Shiller Reference Shiller2015, 20). In the early 1970s, real housing prices rose rapidly for several years, fell during the recessions of 1981 and 1991, and then rose at an accelerated rate until the financial crash of 2007. Up to about 1970, owning a house was not a good investment relative to stocks and bonds. After 1970, it became a major portion of middle-class financial portfolios and thus subject to macroeconomic and local risks (Skinner Reference Skinner, Noguchi and Poterba1994, 191).

My major thesis is that homeowners once looked on their houses as places to live, but now look at them as growth stocks. This is not a new claim. In Irrational Exuberance, Robert Shiller wrote, “Life was simpler once; one saved and then bought a home when the time was right. One expected to buy a home as part of normal living and didn’t think to worry what would happen to the price of homes. The increasingly large role of speculative markets for homes, as well as of other markets, has fundamentally changed our lives” (Reference Shiller2015, 35). My contribution is to point out that one of the fundamental changes has been to make homeowners acutely defensive about new developments that might possibly affect their homes’ value. My theory inverts, or at least complicates, the claim that growth controls cause higher housing prices. It is possible that growth controls themselves are caused by inflating housing prices, which goad homeowners to organize more effectively against developers. It might be better for all concerned if homeowners could again see their homes as steady investments and good places to live rather than a way to get rich.

1.2 Ngrams and the Origins of Growth Controls

Google has a free on-line feature called the Ngram Viewer. It graphs the annual frequency of uses of a word or phrase in Google’s digitized collection of millions of books, scanned mostly from university libraries. (It does not include newspapers or periodicals.) The word or phrase can be used in any context, and simply being mentioned more or less frequently can be a measure of its salience in public discourse.

Ngrams may offer clues about why zoning was adopted in the United States. I had written an article that argued that zoning’s rapid rise and spread in the 1910 to 1930 era was caused by the spread of low-cost automobiles and, more particularly, their adaptations as freight trucks and inexpensive passenger buses, the latter popularly called jitneys (Fischel Reference Fischel2004). Motorized trucks and jitneys enabled industry and apartment houses to relocate from ports, railheads, and central cities to the suburbs. In an early planning publication, a zoning advocate complained, “The motor-truck has enabled the indifferent or the blackmailing industrial concern to threaten to locate its factory in the heart of the loveliest of lawn-decorated suburbs. Formerly a factory had to be near a railroad, but that is no longer necessary. It is, indeed, more desirable for a factory to locate near a labor supply – that is, near a district where labor lives – than to be near a railroad” (L. Purdy et al. Reference Purdy, Bartholomew, Bassett, Crawford and Swan1920, 6). Homebuyers’ reluctance to commit to a large purchase that might be devalued by subsequent development was the main reason responsible developer organizations sought to promote zoning (Weiss Reference Weiss1987).

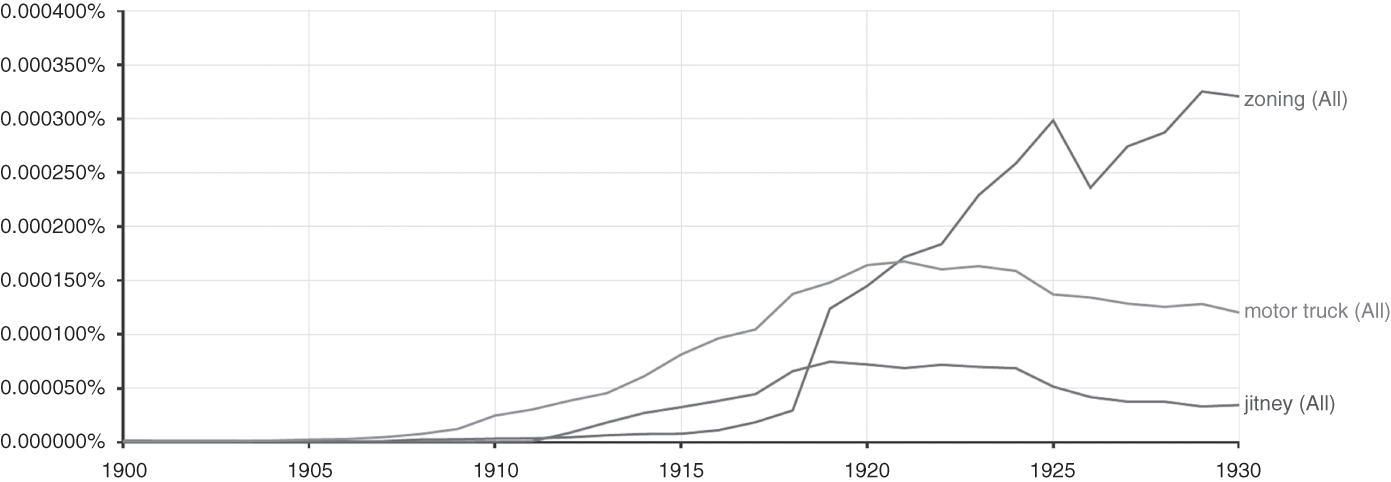

In Figure 1.1, an Ngram for the terms “jitney,” “motor truck,” and “zoning” illustrates a rapid take-off of their use in books during the 1910s. (Both “jitney” and “motor truck” decline after 1925 as the jitney was replaced by the conventional bus and the motor truck became so common as to just be called a truck.) The jitney’s booming popularity caused concerns among real estate developers, who had formerly depended on managing the location of streetcar lines to keep apartment developers out of single-family home areas (Cappel Reference Cappel1991). An article in the New York Times Magazine (1915) noted that opposition to the free-wheeling service was not just from streetcar interests: “Realty associations are backing up the protests of the traction [streetcar] people on the ground that the prosperity and extension of the streetcar service go hand in hand with the development of real estate, which is not fostered by these jitney men.”

Figure 1.1 Ngram for “jitney, motor truck, zoning”

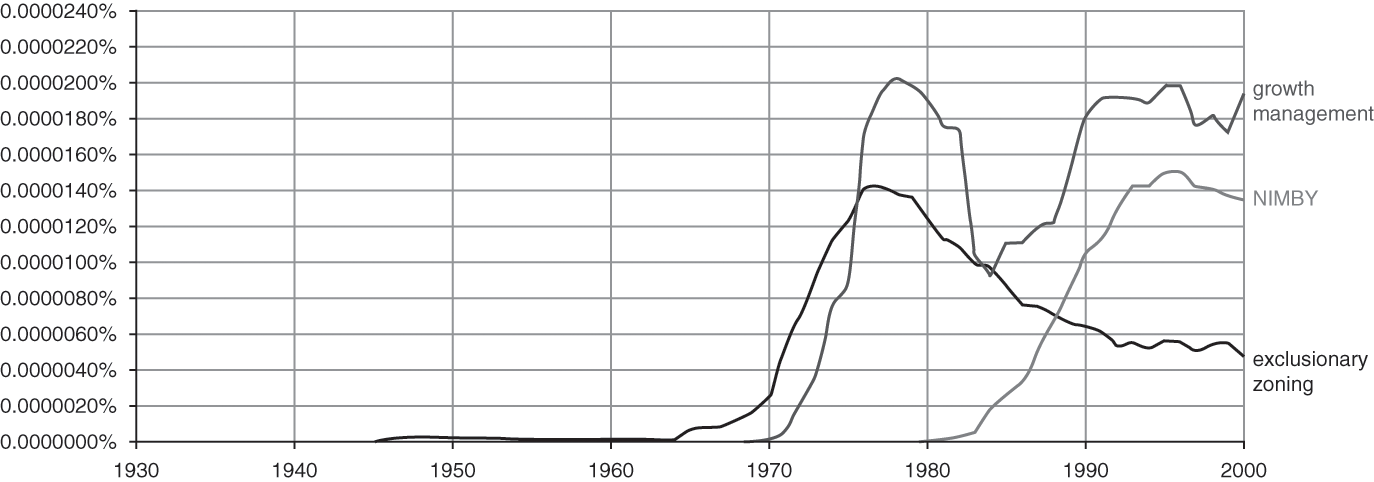

But it appears that land use regulation became notably more restrictive during the 1970s. This is suggested by the Ngrams for terms related to those restrictions: “growth management,” “NIMBY,” and “exclusionary zoning” (Figure 1.2). (“Growth management” is used in the Ngram rather than “growth control” because the latter phrase includes many scientific applications.)

Figure 1.2 Ngram for “growth management, NIMBY, exclusionary zoning”

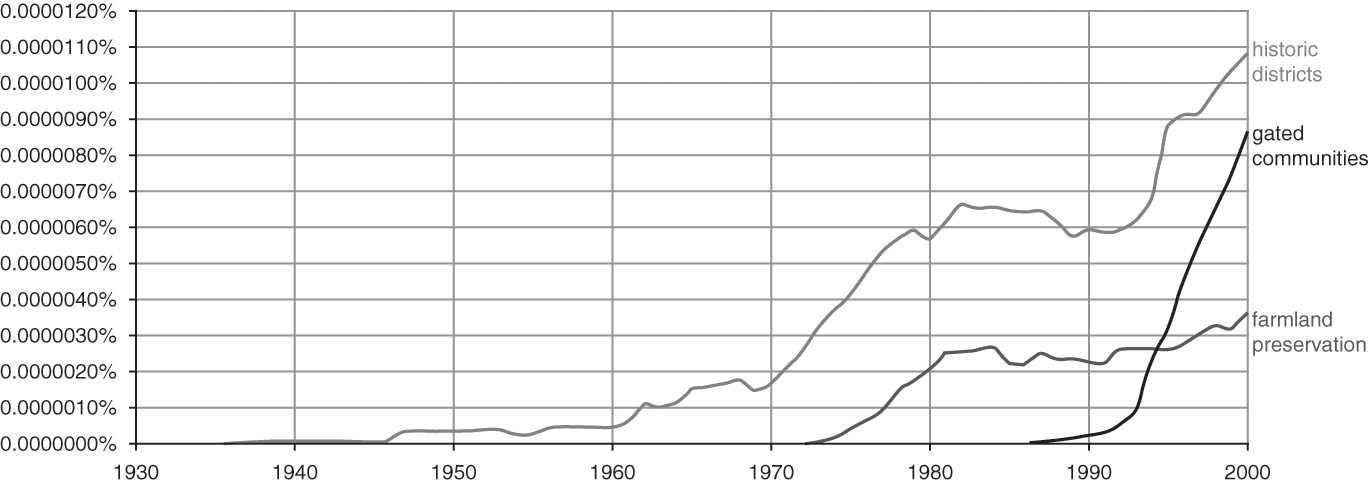

These terms were statistically nonexistent before 1970. The late-century decline in mentions of the pejorative “exclusionary zoning” seems to be roughly offset by the more acceptable means of exclusion embodied by the terms illustrated in Figure 1.3: “farmland preservation,” “gated communities,” and “historic districts,” the last being the subject of Chapter 4 in the present volume by Ellen and McCabe. Similar Ngram patterns, not shown here, can be seen for terms such as “wetland protection,” “downzoning,” “regulatory takings,” and “urban growth boundary.” Land use regulation after 1970 involved a major change from the immediate past, a change that invoked a new vocabulary that is now so pervasive that we may have forgotten that mid-century planners and scholars were unfamiliar with it.

Figure 1.3 Ngram for “farmland preservation, gated communities, historic districts”

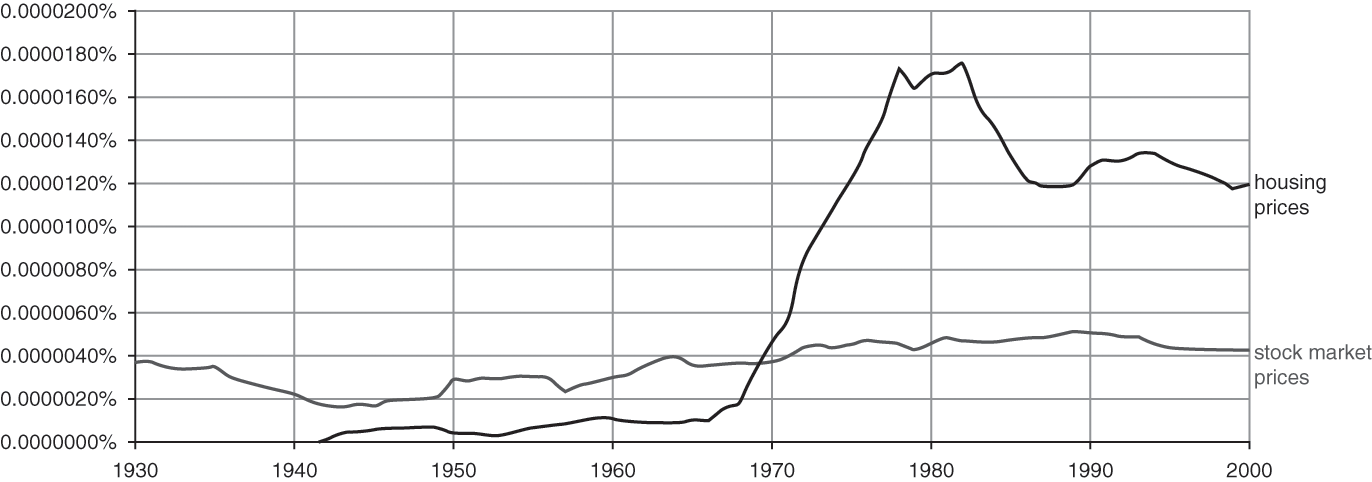

The Ngram that encapsulates the thesis I advance in this chapter is Figure 1.4, which juxtaposes “stock market prices” with “housing prices.” Before the 1970s, mentions in the general literature of housing prices were few relative to stock market prices. People talked and wrote about the stock market, but not much about housing prices. In the early 1970s (the data are smoothed by three-year shoulder intervals), discussion of housing prices zoomed both in an absolute sense and relative to stock market prices. (The Ngram for the more general term “stock prices” is so large as to dwarf the frequency of “housing prices.” Generally speaking, Ngram analysis is most revealing with phrases of comparable frequency, and “stock prices” can refer to cattle and inventories as well as equities.)

Figure 1.4 Ngram for “housing prices, stock market prices”

A similar story is told by the quantitative data on the growth of housing prices and capital gains from homeownership. According to my colleague Jon Skinner, “Between 1955 and 1970, the share of owner occupied housing in total household net wealth hovered around 21 percent. In the nine years between 1970 and 1979, housing wealth climbed to 30 percent of net wealth” (Reference Skinner, Noguchi and Poterba1994, 191). This shift in the composition of wealth portfolios corresponds closely with a fundamental shift in land use regulation. (The rise from 21 percent to 30 percent may not sound enormous, but it should be understood that, as with housing prices, capital gains from home values were much larger in the urban areas of the Northeast and West Coast, as discussed presently.)

My theory holds that inflation in the 1970s, driven initially by the rise in world oil prices by OPEC, made owner-occupied housing a highly desirable asset. The benefit of the tax-favored status of homeownership rises relative to other assets during inflation (Poterba Reference Poterba1984). But this asset has a large downside that was the fundamental premise of my 2001 book, The Homevoter Hypothesis: as an asset, an owner-occupied home is almost impossible to diversify and is subject to risk from changes in the neighborhood and the community in which it is located. Unlike fire and theft, adverse community and neighborhood effects cannot be insured against by homeowners. Homeowners had since the 1910s cared about keeping footloose industry and apartment houses separate from their neighborhoods, but they lacked the organizational ability to forestall community and regional growth that would threaten the upward growth of their home values in the 1970s. The unprecedented rise in housing prices gave homeowners additional reasons to care about public land use decisions (Taylor Reference Taylor2013).

1.3 The “Growth Machine” Prevailed before 1970

Yet homeowners who wanted to control the development process were at a political disadvantage. Conventional public choice theory predicts that organized interest groups will tend to capture the regulatory authority, and housing should be no different. Housing developers had the advantage of being well organized and strongly motivated to control the development process. Sociologist Harvey Molotch (Reference Molotch1976) invented a term for this political control, “the growth machine.” Developers in the early twentieth century were originally in favor of zoning because it served as a kind of insurance policy for prospective homebuyers (Fogelson Reference Fogelson2005; Weiss Reference Weiss1987). With zoning in place, homebuyers could be assured that subsequent neighborhood changes would be less likely to adversely affect their large investment.

Developers did not promote zoning with a starry-eyed faith in regulation. They knew that letting this particular genie out of the bottle could be hazardous. J. C. Nichols, a pioneer in developing (privately) planned suburban communities in Kansas City, also advocated zoning, but, as his biographer points out, “Real estate operatives slowly came to realize that by accepting zoning and getting themselves appointed to zoning boards and commissions, they could influence governmental and public decisions in their favor to an even greater degree than before” (Worley Reference Worley1990, 90 [my emphasis]). Marina Moskowitz describes how 1920s land use commissions were dominated by a pro-development “professional-managerial class” (Reference Moskowitz1998, 311). Developers were willing to cater to homeowners’ desire to avoid localized external costs, but they did not want established homeowners to control zoning.

In the pre-1970 era, established homeowners sometimes did oppose development, but they were usually unsuccessful. In his lengthy history of the planning profession, Mel Scott describes two instances of suburban homeowners opposing apartment developments (Reference Scott1969, 458) and public housing (p. 418), but the mentions are surprisingly few, and the opposition did not halt all development. Growth controls and similar constraints are not mentioned at all, even though Scott was influential in the movement to preserve San Francisco Bay. His history laments that planners had little to do with zoning, and his wide-ranging examples could have been taken by Molotch as evidence in support of the dominance of the developer-dominated growth machine. (Molotch in his original paper was more concerned with exploring the implications of his idea than testing it against alternative hypotheses. A later elaboration of the theory with John Logan did discuss some contrary evidence about the effect of growth controls, but Logan and Molotch [Reference Logan and Molotch1987] dismiss it as a minor issue, a conclusion they reaffirmed in the preface of the 2007 reissue of their book.)

There is little doubt that zoning regulations were relatively permissive before the 1970s. This is not to say that developer interests always got what they wanted. But they were able to manage opposition through negotiation with local authorities. A well-known example was the development of the original Levittown (as it became known) housing tract in Hempstead, Long Island (Kelly Reference Kelly1993). The Levitt company acquired experience building wartime housing for workers and adapted its mass production techniques for suburban houses. The company needed Hempstead to change its zoning laws to accommodate its construction methods, particularly the town’s requirement that units have basements rather than the concrete slab foundations that Levitt wanted to use. There was some opposition to the project from neighbors, but the town council and planning authorities gave the builders almost all of the changes they requested. Levitt packed one town hearing with recent World War II veterans who were looking for housing. The fledgling suburban newspaper Newsday was eager to expand its subscriber base and wrote numerous articles and editorials in support of Levitt. The newspaper’s occasional screeds against unnamed “elitists” in nearby communities who opposed expansion of Levittown indicate both that there was opposition and that it was ineffective.

1.4 Homevoters Joined and Sustained the Environmental Movement

After 1970s inflation caused homeowners to demand more protection of their assets, they needed to break the hold of the pro-development forces on zoning regulation. The increasing value of their homes created a common interest among homeowners, but they needed access to institutions to control growth. Part of the access came from the local political process. In smaller governments, such as those of the suburbs, homeowners simply elected officials who were more attuned to their interests. In a series of nuanced histories of regulation by suburbs in the Boston area, Alex von Hoffman found that in the 1970s, developer-friendly zoning was displaced by procedures that reduced total homebuilding. One long-time developer whose family had been local farmers lamented the unexpected popular opposition to further development, “Paradoxically, I sell to people who become my enemies” (von Hoffman Reference Von Hoffman2010, 17).

Where the “growth machine” was better entrenched, homeowners needed to adopt devices that could do an end run around zoning or add layers of review so that the local government’s decision to rezone or otherwise accommodate new development would not be the final word. In political affairs, homeowners became an interest group that I have labeled “homevoters.” They use their local votes and other political activities to protect and promote the value of their owner-occupied homes.

The environmental movement in 1970 provided the main vehicle for homeowners to add the layers of regulatory review to gum up the growth machine. The environmental laws themselves were not obviously designed for this purpose. They were largely motivated by concerns that were either nonurban – wilderness preservation and public lands management – or were applicable to urban development only in an indirect way, such as water quality and air pollution (Sax and Conner Reference Sax and Conner1972).

Environmental organizations had always been at a disadvantage when they were opposed by development organizations. Even with new laws that offered them more leverage, they suffered from the fact that what they were seeking was the provision of a widely shared public good that represented a small fraction of the public’s consumption budget. But they did have institutions organized around outdoor activities, and this offered a mutually advantageous merger of interests with homevoters. Homeowners had a rising demand to control development in their neighborhoods, but not an effective antigrowth organization. Environmental groups provided the organization, and they were willing, even eager, to extend their goals to include protection of suburban open space as well as that of non-farming rural areas. Bernard Frieden (Reference Frieden1979) was one of the first to systematically describe the new use of environmental standards to retard housing development in the San Francisco Bay Area.

This deal – largely unconsciously entered into – created an offset to the growth machine. Membership and contributions grew as environmental organizations allied themselves with homeowner interests. (Adam Rome [Reference Rome1994] describes the early history of this alliance, and Richard Walker [Reference Walker2007] offers a largely admiring view of its early evolution in Northern California.) The new antigrowth machine passed state laws mandating second review of local zoning decisions (Bosselman and Callies Reference Bosselman and Callies1971), expanded the legal standing of objectors to growth both within the community and to outsiders (Sterk Reference Sterk2011), and, somewhat paradoxically, embraced preservation of farmland on the edges of urban areas. (Paradoxical because in truly rural areas, environmental interests in water quality especially have often been at odds with the interests of commercial farmers and ranchers.)

One might ask whether the newfound power of homevoters was simply an extension of previous trends, amplified by a new environmental consciousness of the 1970s. It is difficult to prove a negative, but histories of environmental thought indicate that the tension between industrialization and the pastoral ideal began in the early nineteenth century (L. Marx Reference Marx1964). It was if anything disdainful of things urban. As a political movement, what became environmentalism was often the domain of patrician elites, who often as not expressed a general contempt for the lower classes through a sometimes painful-to-read eugenics argument (J. Purdy Reference Purdy2015). Environmentalism for the first two-thirds of the twentieth century was concerned mainly with nonurban areas.

Christopher Sellers argues that populist environmentalism took root in the suburbs in the 1960s, and that provided an opportunity for new directions: “As national conservation groups watched the many local and regional groups singling out pollution and other suburban issues, they realized that this new environmental agenda had recruitment potential” (Reference Sellers2012, 272). The Sierra Club’s membership grew from about 113,000 in 1970 to almost a million by 2000. In 1969, its former director, David Brower, founded a more activist organization, Friends of the Earth, whose motto brilliantly summarized the merger of environmental and homeowner interests: “Think globally, act locally” (Walker Reference Walker2007, ix). Other organizations formed specifically to “act locally” included San Francisco’s People for Open Space (now the Greenbelt Alliance), and they have been quite successful. By 2006, the nine Bay Area counties had more than a million acres (of about 4.4 million total) perpetually protected from development, an area that exceeded the existing urban and suburban land area (Walker Reference Walker2007, 108).

One reason for the success of the marriage of environmentalism and suburban concerns was that environmentalism offered a unifying ideology that allowed homevoters to avoid talking about home values directly. Growth controls are the product of collective action at the local level, and establishing collective action requires a unifying public discourse (Ellickson Reference Ellickson1991). Declaring that the goal of preserving local open space is to maximize voters’ property values is actually somewhat divisive. It also seems selfish in a public setting. It invites invidious comparisons among residents. (“Oh, your home is so much more important than mine?”) Environmental justification for policies that just happen to increase existing home values is a shield against outside criticism of exclusion and a source of unification among homeowners with otherwise unequal interest in the policies. It serves the same function as the “hearth and home” ideology that brought homeowners together to support zoning in the early twentieth century (Fischler Reference Fischler1998; Lees Reference Lees1994).

1.5 Sources of National Variation: Shifts in Industry and Differences in Local Government

My explanation for the rise of growth controls, then, is that they were the interaction of a shift in demand for home value protection in the 1970s and an increase in the supply of regulatory devices that operated outside the traditional growth-machine framework. These political and social forces displaced pro-development forces in local governments. But this deals with only one part of the puzzle. The now-conventional wisdom among urban economists is that stringent land use regulations account for the excessively high housing prices in Northeast and West Coast urban areas compared to those in the rest of the United States.

Peter Ganong and Daniel Shoag (Reference Ganong and Shoag2013) have shown that states that now have the highest housing prices and the most land use litigation (an indicator of land use regulation) had not, before 1970, led in either of those categories. Their model demonstrates that the regional regulations have had important effects on internal migration, significantly reducing the ability of Americans in poor states to better their lot by moving to richer areas. Numerous other studies confirm the unusual differential between housing prices on the coasts and elsewhere in the nation. As Karl Case observed, “Prior to 1970, house prices moved slowly at about the rate of inflation or slightly below, and regional differences, while they existed, were relatively modest by current standards” (Reference Case, Noguchi and Poterba1994, 29).

But what caused land use regulations to ramp up so much more in those states after 1970? My answer is that exogenous forces shifted the national demand for labor in ways that made the metropolitan areas of the West Coast and, soon after, the Northeast more attractive to high-income, college-educated people. I approach this explanation by introducing the dog that did not bark. The energy crisis of the 1970s induced a substantial relocation of manufacturing employment from the Rust Belt – the cities of the Great Lakes and the Ohio Valley – to the Sun Belt. States of the South and Southwest experienced substantial population growth from internal migration. But this migration did not result in an unusual increase in housing prices. Developers responded to the higher immigration by building more housing, which kept new and existing home prices from rising unduly (Glaeser and Tobio Reference Glaeser and Tobio2008). Demand for housing shifted out, and supply responded fairly quickly.

Another internal industrial shift occurred at almost the same time. The largest cities of the West Coast and (a decade later) the Northeast were at the forefront of the shift from manufacturing to high-tech-driven services (Glaeser and Gottlieb Reference Glaeser and Gottlieb2009). The introduction of computer technology reduced the demand for lower-skilled manufacturing jobs. Manufacturing was replaced in cities by high-skilled service jobs such as finance and computer software development. Global forces such as the reduction in trade barriers and the rise of Asian manufacturing capacity further accelerated the American shift from manufacturing to knowledge-based services, which played to the historical advantages of the large, trade-oriented cities on the West Coast and in the Northeast. Such shifts in regional advantage have long been a part of American economic growth, as historical geographer Daniel Meinig (Reference Meinig1995) has shown.

The growth of West Coast computer industries, for example, increased their demand for highly educated workers in the 1970s and 1980s. The workers bought housing at a time when national inflation fueled the demand for owner-occupied housing. As its value rose, homeowners on the West Coast demanded even more protection. As described previously, organizations such as the Sierra Club and People for Open Space were available to offset growth-machine politics. The judiciary in California and later Oregon and Washington became more hospitable to growth controls (DiMento et al. Reference DiMento, Dozier, Emmons, Hagman, Kim, Greenfield-Sanders, Waldau and Woollacott1980; Galvan Reference Galvan2005).

In the Northeast, the fragmented structure of local government and traditions of local democracy made it possible for local homevoters to take the reins of zoning and planning. The knowledge classes of workers started in the suburbs to adopt growth control, and their state representatives and the judges they appointed soon undermined the growth machine (von Hoffman Reference Von Hoffman2010). Towns formerly hospitable to apartment house development reversed course, largely in response to local voters’ demands (Schuetz Reference Schuetz2008). Even larger central cities such as Washington, DC and New York have turned from their formerly enthusiastic embrace of development as they have become repopulated with affluent homeowners (Schleicher Reference Schleicher2013). The supply reduction in the metropolitan West Coast and Northeast was further facilitated by the fact that the new workers were high income and highly educated, just the stratum most eager to protect the value of their owner-occupied homes. In contrast, the migrants from the Rust Belt to the Sun Belt were typically lower income. Both political participation and demand for environmental quality tend to rise with personal income.

The Sun Belt had another historical quality that made it less hospitable to growth controls. Local government in the old South was historically weak compared to the North. The reason, I have argued, is because of slavery and its legacy, racial discrimination (Fischel Reference Fischel2009, chap. 5). Blacks and whites were not evenly distributed across the South, and so there would inevitably be localities where a large majority would be African American. Despite voter disfranchisement efforts, some blacks could vote, and they could thus influence the outcomes of local elections. This would not just create pressure for integrated schools. It would, even in the absence of integration, divert resources from white institutions. Thus Southern state legislatures were loath to grant localities much leeway to provide schools and other local public goods (Bond Reference Bond1934; Key Reference Key1949).

The county, with its largely state-appointed officials, was the primary unit of local government in the old South. The county was maintained as the primary unit for school districts and thus the focus of other local government after the civil rights laws undermined racial segregation. Subsequent local demand to create smaller units in the South was largely frustrated by the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which required the approval – rarely given – of the U.S. Justice Department for local government reorganizations (Motomura Reference Motomura1983). Thus both racial segregation and desegregation made the county the default unit of government in the South. Exurban counties tend to be more pro-development in their politics (Anderson Reference Anderson2012), and this appears to apply especially to the South.

The other institution that the South generally lacks is the voter initiative (www.iandrinstitute.org). The larger units of government in the West, where counties rather than cities often governed the exurban land, might be dominated by developer interests. But county and city land use policies are hemmed in by the use of the voter initiative. Homeowners and environmental organizations can thus bypass the influence of the growth machine with ballot initiatives to create open space and even stop individual projects. The county governments of the old South remain in the grip of the growth machine because their voters lack the initiative. Even where land use issues are resolved by sub-county governments, as in Texas, the use of the initiative in land use issues in highly constrained by the state’s courts (Callies, Neuffer, and Caliboso Reference Callies, Neuffer and Caliboso1991, 75).

1.6 The Importance of Irreversibility and a Note on Renters

The catalytic event in my account of the rise of the homevoters and growth controls is unprecedented peacetime inflation in the 1970s. Inflation has since dropped, and it might reasonably be asked why this has not led to a reversion to the growth-machine model of zoning that prevailed before the 1970s. The growth-control model has weathered disinflation and three serious recessions in which housing values declined, especially in 2008, but also in 1981 and 1991. What processes keep the growth-control regime afloat when home values are actually declining and inflation is moot?

One was the deliberate attempt to make growth controls irreversible. From an economic point of view, irreversibility makes a lot of sense for homevoters. They need to convince buyers that the rules that make their homes valuable – the rules that create future scarcity – will not be easily changed. (The classic article on the need to create irreversible commitments to establish monopolies over durable assets is Ronald Coase [Reference Coase1972].) Ordinary zoning laws from the start were intended not to be easily changed. Minor exceptions administered by zoning and planning boards are subject to rules of procedure such as written notice to neighbors and demanding criteria about unique characteristics of the property in question (Reynolds Reference Reynolds1999). Major rezonings are likewise subject to more rules than most other changes in police-power regulations. One example is the “twenty percent protest clause,” which empowers nearby property owners to demand that changes in zoning be adopted by a supermajority of the governing body (Bartley Reference Bartley1953, 370).

These forces of stability have been supplemented since 1970 by both procedural and substantive changes in land use law. In some states (New York and California), rezoning often involves a state-required environmental impact statement, whose adequacy can be challenged by citizen groups (Sterk Reference Sterk2011). In other states, like Vermont, a state or regional review body can review and veto pro-development decisions. Some states have taken more seriously the requirement for conformity with the master plan (although this can also protect developers from downzonings), and hostility to small-scale rezonings is embodied in the pejorative term “spot zoning.”

A more innovative device is the use of conservation easements. These convey the right to develop unused land to a conservation organization, which promises to prevent development, usually in perpetuity. This resolves the anxiety of prospective buyers that the nearby cornfield or stand of trees might someday be rezoned and used for more homes to compete with the existing homes or at least sully their view. Conservation easements have been made financially attractive to donors in many states through the use of tax deductions and even tax credits (Pidot Reference Pidot2005). Some local governments have seized on them as a way of tying the hands of future officials (Serkin Reference Serkin2010). Conservation easements have been widely used in farmland preservation near cities. Historic districts (rather than just single monuments) have also added to the transaction costs of redeveloping older areas for more intensive “infill development.”

The persistence of growth controls is also due to evolving community values. Once open space and large-lot zoning districts are established, the homebuyers who most care about them are apt to end up in communities that establish them. This sorting by preference is part of the well-known model of Charles Tiebout (Reference Tiebout1956). Even if the original growth controls were created solely to protect home values (and not from preference for open space), the later homebuyers who bought with the expectation of open space as part of their purchase are more likely to want existing land uses to persist. An implication of the institutionalization of growth control devices is that the regulatory framework becomes easier to use by citizens who do not have as intense an interest as homeowners. The transformation of land use regulation was undertaken, I submit, by homeowners, but, once transformed, land use regulation became more accessible to all.

Vicki Been, who is a professor at NYU Law School and Commissioner of Housing Preservation and Development in New York City, emphasized in her comments on this chapter the need to account for what in her experience is the homevoter-like behavior of urban renters. New York’s renters seem as active in policing neighborhood change as suburban homeowners. In the homevoter model, renters should have less interest in land use change because they cannot capitalize on the benefits of neighborhood quality. If local conditions get better and the tenants move away, their landlord gets the benefit of neighborhood improvement in the form of higher rents. Even if the leaseholder does not move, higher rents would offset to a large extent the benefits of neighborhood improvement.

Both of these mechanisms are attenuated by the existence of rent control (Fischel Reference Fischel1991). Improved neighborhood conditions do not result in higher rents under rent control, and renters protected from rent increases are less likely to move and thus can enjoy the improved neighborhood quality. In these conditions, renters should behave much like homeowners in the political realm, even though they cannot fully capitalize on the benefits of neighborhood improvements. New York City renters are also an especially well-organized group – they regularly battle landlords in the political realm – and should benefit from the wide availability of growth controls.

It is important to understand, however, that New York City’s conditions are relatively rare. Two-thirds of the city’s housing is renter occupied, among the highest in the nation, and it should not be surprising that renters rather than homeowners get the most political attention. It is one of the few cities that has had rent control and related tenant protections for almost a century. When economists make models of local government, they usually want to capture the experience of a majority. Outliers like New York are always interesting to test the limits of the homevoter model (as Been, Madar, and McDonnell [Reference Been, Madar and McDonnell2014] have done), but confirmations of the homevoter theory in the nation’s second-largest city, Los Angeles (Gabbe Reference Gabbe2016; Morrow Reference Morrow2013), as well as smaller cities such San Jose (Holian Reference Holian2011) and various municipalities in Canada (McGregor and Spicer Reference McGregor and Spicer2016), suggest that projecting the political influence of New York’s renters to other places may not be warranted.

1.7 Alternative Explanations for the 1970s Growth Controls

The two alternative – or supplemental – explanations for the rise of growth controls in the 1970s are (a) the rapid completion of the interstate highway system and the suburbanization it facilitated and (b) the civil rights movement and the accompanying unrest in central cities and the political response to it. Both of these surely contributed to some of the demand for growth controls.

The interstate highway system was an enormous undertaking and was special in two important ways (Swift Reference Swift2011). One is that it was built within a relatively short period of time, between 1956 and 1972. The other was that it was almost entirely financed and directed by the federal government. Limited-access highways are highly disruptive to the cities and neighborhoods through which they are built. Locations immediately adjacent to them have their neighbors displaced or effectively cut off from everyday commercial and personal connections. Railroad construction did that in the nineteenth century, too, but they were different in several ways. Grade crossings were more feasible for railroads, and the location of their routes was subject to some degree of local control because the railroads needed local facilities (terminals and stations) to be integrated with the through lines. The railroad builders could be high-handed bullies, but their need for continuing local cooperation in the indefinite future stayed some of their excesses.

The builders of the interstate highway were almost entirely federal and state agencies. Their need for local input and cooperation was much less than that of the railroad builders. As an engineering-based group, the highway designers were short of models of behavioral response. The designers expected that the highways would promote urban growth, but they did not anticipate the suburbanization that it caused. The decision to run many of them through central cities was based on the belief that doing so would reduce traffic congestion in those places. Federal planners had contemplated – and rejected – using tolls to finance the system, but no thought was given to using tolls to manage the inevitable congestion that an urban freeway is subject to.

The heavy-handed tactics of the highway builders generated a species of protest in the 1960s called freeway revolts (Mohl Reference Mohl2004). These ad hoc organizations were precursors to the antigrowth coalitions of the 1970s, and many of them continued their lives long after the highways were built – or not built, if the organization was successful. They are important for my argument that growth controls were a bottom-up movement because they did overcome the torpor of local residents – what economists call the free rider problem – in combatting local change that threatens their home values. A proposed new highway was large enough and adverse enough that it got homeowners out from in front of their TV sets to attend hearings and protest meetings.

Thus the interstate highway system could have contributed to the growth-control movement in two distinct ways. One was by increasing suburbanization by making it easier to live farther from the city (Baum-Snow Reference Baum-Snow2007), and the other was by generating opposition groups that became part of the nucleus of antigrowth organizations in the 1970s. The difficulty with the suburbanization argument is that most of the evidence does not point to any special increase in the measured rate of suburbanization in this period (Mieszkowski and Mills Reference Mieszkowski and Mills1993). The way that most economists measure suburbanization is through population density and price gradients, the rate at which density of population or price of housing declines as one moves away from the center of the city. These measures began to decline (in absolute value) in the late nineteenth century with the invention of electric-powered street railroads, and they have kept declining more or less continuously ever since. Suburbanization does not seem to have accelerated during the period 1956 to 1972, when the interstate highways were built.

Local resistance to major highway development was indeed an occasion for citizen action, but its underlying concern was home values. Louise Dyble details the galvanizing effect on local politics of proposals to build new bridges and freeways in Marin County, north of San Francisco, in the 1960s. This antigrowth coalition was successful in stopping most new highway development and making Marin County a pioneer in the growth-control movement. Dyble concluded, “A close look at the dynamics of regime change in Marin reveals that power in the county shifted only when the real value of exclusivity, open space, and natural beauty became clear to property owners. Marin’s celebrated environmentalism was founded on the value of real estate” (Reference Dyble2007, 59).

The other phenomenon that may have made the 1970s land use policies different was the product of the civil rights movement. Desegregation of central city schools often pushed middle-class whites to the suburbs (Boustan Reference Boustan2010; Reference Boustan2012). Even if the rate of suburbanization was not much changed by that, it is possible that the nature of suburban zoning was altered by it. A population increase in a developing suburb in the 1950s was not difficult to accommodate with new public facilities. More families meant towns had to build more schools, but the expanded tax base more or less covered the cost. An important offshoot of the civil rights movement, however, insisted that suburbs had to accommodate low-income people and minorities along with market-rate development (Downs Reference Downs1973; Sager Reference Sager1969).

In the past, allowing more growth brought more of the same sort of people to the suburbs. After political and legal pressure began to be applied to accommodate a variety of housing, general population growth looked less attractive to suburban voters. The thinking by homevoters might have been, if we have to take blacks and the poor along with everyone else, maybe we would prefer to have no growth at all. Of course, public expressions of such ideas was unacceptable, so an alternative rationale for stopping growth was necessary. Preservation of the environment by preserving open space – even environmentally problematical open space like commercial farmland – began to be especially popular (Schmidt and Paulsen Reference Schmidt and Paulsen2009).

As evidence for this, I would note that the two states that have imposed a long-standing obligation on communities to accommodate the construction of low-income housing, Massachusetts and New Jersey, are also the states with by far the largest number of local initiatives to preserve farmland and other open space (Banzhaf et al. Reference Banzhaf, Oates, Sanchirico, Simpson and Walsh2006). The primary means by which communities discharge their state-imposed obligations is a tax on developers of market-rate housing, called “inclusionary zoning.” Such a tax depends on making market-rate housing scarce, which is what growth controls do (Schuetz, Meltzer, and Been Reference Schuetz, Meltzer and Been2011).

On the whole, however, it seems difficult to pin too much on the civil rights backlash as a cause of growth controls. Real pressure to accommodate low- and moderate-income housing exists in only a few states. Politically liberal communities, which one would expect to be sympathetic to civil rights concerns, seem actually more inclined to limit housing growth than others (Kahn Reference Kahn2011). And I have argued that a suburban majority is not all that opposed to them even there (Fischel Reference Fischel2015, chap. 4). A Massachusetts initiative that would have eliminated the obligation to accommodate low-income housing was easily defeated in 2010. Substantial majorities opposed it in all but one of the suburban counties of Boston, which faced the most pressure from the state law that required inclusionary zoning.

1.8 Reflections on Reform: Regionalism and Takings

A substantial number of economists now believe that regional housing supply in productive areas has been adversely affected by growth controls and that the excessively high housing prices have reduced American productivity and promoted inequality (Ganong and Shoag Reference Ganong and Shoag2013; Hsieh and Moretti Reference Hsieh and Moretti2015). Relatively few of these studies have addressed what to do about it. The usual idea is that some higher-level government – the federal or state governments, sometimes a regional body – should intervene to override unreasonable local behavior. Economists typically commend devices such as “a simple system of fees, much like congestion tolls, that cover whatever social costs there are from taller buildings and other consequences of increasing urban density” (Glaeser Reference Glaeser2011, 161). Developers willing to pay for their social cost should not be stopped by local governments or NIMBY forces. The higher government, able to internalize both the political benefits as well as the costs of development, would override parochial interests.

Bob Ellickson suggested a different approach to the problem (Reference Ellickson1977). He presciently identified the burgeoning growth-control movement as at least partly a legal problem. Voters in local government who wanted to control growth by downzoning available land could do so without having to face much of an opportunity cost. Police-power regulations are generally not compensable, and rational governments – a concept embraced by the “median voter” model in public economics – are apt to respond to the low cost by doing too much regulation. Ellickson advocated using the regulatory takings doctrine to make local officials (and presumably local voters) raise taxes to compensate development-minded landowners if the local government wanted to unreasonably downzone land to prevent development.

Neither of these approaches has worked. Land use policies of the state and federal governments have more often worked against development than for it (Fischel Reference Fischel2015, chap. 2). The multiple layers of review have generally been of the double veto variety: only in rare instances do they allow developers to go from a local “no” to a state or regional “yes.” The expansion of legal entitlements and their wide and indefinite distribution has greatly extended the time that development takes, when it can be done at all.

The underlying reason for state governments’ reinforcement of local preferences is the geographic basis for representation in state legislatures. Americans do not select their legislatures from statewide party lists, as parliamentary systems do. Americans elect legislators from local districts whose boundaries usually correspond to some set or subset of municipalities. The saying “all politics is local” is an Americanism – Ngram frequency three times that of British English – because it really is local in the United States. State legislatures remain amalgams of local governments even after the 1960s reapportionment decisions declared that they must be selected according to the principle of one person, one vote. It is possible that the reason American judges feel the need to declare that localities are formally “creatures of the state” is that so many other institutional arrangements work to make the state the creature of localities.

The viability of the takings doctrine is confounded by the numerous parties, most of them not a government that could incur constitutional liability, that contribute to stalling development. James Krier and Stewart Sterk (Reference Krier and Sterk2016) find that the modern takings litigation has had remarkably little success for complaining landowners and developers. Moreover, local land use regulation is so popular that court efforts to rein it in have led to state constitutional amendments and threatened supreme court reappointments. New Jersey voters adopted a state constitutional amendment in 1927 to authorize zoning after its courts had struck it down (National Municipal Review 1927).

The economic-historical account of the rise of growth controls suggests a different approach to reform. It is surely true that growth controls cause housing prices to rise. But it is equally true, I argue, that growing housing prices cause homeowners to demand more regulation to protect their asset. They don’t care whether the additional regulation is more stringent zoning, private covenants, or environmental lawsuits. Home value inflation begets a demand for more regulation, which begets more home value inflation.

The large metropolitan areas of the Northeast and the West Coast are historically unusual in that the demand for housing in these regions increased at a time – the 1970s and 1980s – when the balance of power in land use regulation shifted away from development-minded parties toward seated homeowners who wanted to protect the value of their largest and largely uninsurable asset. I point this out again to suggest that growth control policies are not usefully parsed by region. The states and cities of the Northeast and West Coast do not have fundamentally different legal frameworks from those in other states. Land use laws are sufficiently similar that law professors can put together casebooks and courses that can realistically prepare students to practice (after bar exam study) land use in any state. This suggests that if economic shifts occur that make Chicago and St. Louis the favorite destinations of high-skilled, college-educated workers, the cities of the Midwest will become the centers of growth controls and rising housing prices.

1.9 Demand-Dampening Policies to Mitigate Growth Controls

The purpose of this exercise in recent economic history is to understand what types of policies might work to make housing supply more elastic in regions that are now repelling firms and lower-income immigrants by their high housing prices. Accommodating growth in the Boston-to-Washington corridor and in the larger cities of the West Coast is important for national economic growth and for reducing the level of income inequality in the United States. It is clear from experience that the courts are not able or inclined to protect the interests of development-minded landowners. Federal and state policies that attempt to increase supply or lower local barriers are inevitably frustrated by the political power of the locals and the NIMBY alliance with high-minded environmental goals.

I have argued here that the primary reason people participate in stopping development is their concern with their home values. The policies that I mention next are designed to undercut excessive concerns, but it might reasonably be asked at the outset whether institutional change is actually possible even if homeowners were no longer excessively touchy about nearby development. I mentioned earlier that one reason for the persistence of growth controls in the absence of home value inflation is that the original institutions were designed to be difficult to undo. There is a built-in hysteresis to growth controls that may warrant just leaving them alone.

The evidence that we have about the growth of growth controls suggests that voters make them more stringent as their home values rise (Lutz Reference Lutz2015). Surveys in California show that voters are less inclined to adopt growth controls when home values are no longer rising (Baldassare and Wilson Reference Baldassare and Wilson1996). My own informal evidence is consistent with this. During the housing boom of 2001 to 2007, a new layer of local regulation was developed to provide additional protection for urban neighborhoods. They are called “neighborhood conservation districts,” which give neighborhoods the right to review local development independent of citywide zoning (Fischel Reference Fischel2013; Lovelady Reference Lovelady2008).

What is conserved by the “conservation districts” is the value of existing homes, especially in high-demand areas where city authorities might be inclined to shoehorn some unwelcome development or where existing zoning is not tight enough to prevent an unlovely renovation next door. They differ from historic districts in that the neighborhood does not have to be historic, and they differ from private covenants in that consent of all property owners is not necessary to establish the district. I undertook an online survey of neighborhood conservation districts to see what they were doing, but I noticed an interesting break. After the housing crash of 2007, almost no new districts were formed. Once housing values stopped rising, I infer, residents became less interested in going to the trouble of forming districts.

So perhaps the best that can be expected from demand-dampening policies is to slow down the growth of growth controls, not reverse them. This may be too pessimistic, however. There are signs that the centers of large cities are no longer repelling middle- and high-income people. Indeed, one of the manifestations of the back-to-the-city movement is that the affluent newcomers demand neighborhood growth controls to protect their investments. Unlike the suburbs, though, big cities have an array of other interest groups to offset the growth of the homevoter population. If the homevoter population in the bigger cities can be made less frantic about its assets, it is possible that creative reforms supported by developers, planners, and other stakeholders would have a chance (Hills and Schleicher Reference Hills Roderick and Schleicher2014).

The demand-dampening reforms themselves are mainly to reduce the tax advantages of homeownership. The two big advantages of owning this asset as opposed to most others is the lack of taxation of the implicit rent that owners “pay” to themselves and the explicit exemption of the first $500,000 of realized capital gains for homes of a married couple (Follain and Melamed Reference Follain and Melamed1998). The first advantage – the lack of recognition of imputed rent – would largely be undermined by eliminating the mortgage interest deduction from federal and most state income taxes. This is an imperfect way to tax implicit rent, since it leaves untaxed all the implicit rent for people who have no mortgage – usually the elderly and the very rich. But actually taxing implicit net rent is administratively daunting. Doing so would require all homeowners to file their taxes as if they were small business owners, listing an invisible-to-them hypothetical annual rent and keeping track of maintenance and depreciation costs as well as local taxes and mortgage payments.

The mortgage deduction is sometimes regarded as inconsequential because only a small fraction of taxpayers – those in high brackets – find it worthwhile to itemize their deductions. If you don’t itemize and instead take the standard deduction, goes the story, you don’t get any benefit from the mortgage deduction. This is probably wrong. The standard deduction was conceived as a device to save administrative hassle on the part of taxpayers. The amount of the standard deduction is based on what typical taxpayers in that income bracket could have deducted (Brooks Reference Brooks2011). Reducing one of the usual itemized deductions – mortgage interest paid – should in principle result in a similarly reduced standard deduction. Whether Congress would actually do this is not clear, but doing so would be consistent with the original function of the standard deduction.

More important in my mind is to equalize the tax treatment of capital gains from housing with that of other assets. This is probably a larger source of political distortion than the mortgage subsidy. Homeowners through the 1970s enjoyed the mortgage deduction, but faced a heavily constrained capital gains exemption in that a home of equal or greater value had to be purchased. Homeowners’ excessive attention to the value of their home began, I submit, when they started to think of their homes as a growth stock rather than a steady investment.

A modest, income-contingent subsidy to homeownership in the form of a mortgage deduction (or a tax credit) would serve the national interest in promoting a homeowner society (Glaeser and Shapiro Reference Glaeser and Shapiro2002). The more reasonable and practical reform would be to treat capital gains on homes the same as capital gains on other assets. It may be that we want to tax capital gains more lightly than ordinary income, but equalizing the tax rates among all assets would have both economic and political advantages. Land use regulation could proceed more rationally and humanely if homeowners were encouraged to hold other assets besides their homes.

Practical people may argue that the tax subsidies to homeownership are too well entrenched to be modified significantly. Homebuilder organizations and the multitude of homeowners themselves create a formidable political barrier to reform. This may be too pessimistic. Homeowners are powerful at the local level, but their interests are too diffuse at the national level to form a strong lobby. Homebuilders are well organized and formidable at the national level, but perhaps they would support some moderate reforms if they were persuaded by the arguments of this chapter. The subsidies to homeownership stimulate the demand for housing – good for homebuilders – but cause a political response – growth controls – that restrict supply. Homebuilders might have fewer regulatory problems, of which they complain often, if homes were not regarded as a major source of capital gains for their owners.

Author’s Note

I thank without implicating Vicki Been, Lee Anne Fennell, John Logan, and Harvey Molotch for helpful comments.

Necessity, it is said, is the mother of invention.1 This wonderful volume studies innovation in housing policy. This chapter asks why we need innovation in our housing policy, or rather what is changing to make our current housing policy inappropriate, to the extent that it made sense in the first place. I argue that changing transportation technologies have created opportunities for economic growth, but that land use regulations and other housing policies reduce the gains from these technological improvements. In order to capture the gains from new transportation technologies, and to help reverse the slow economic growth we have seen in the United States in most of the period since 1970, we need a housing policy that matches our current (and future) transportation system.

* * *

In discussions of the American economy, the transportation industry and transportation innovation plays a central role. Politicians regularly point to the health of the transportation industry as an indicator of the economy’s broader well-being. Think of Charles Wilson’s famous (mis)quote that “what’s good for General Motors is good for the United States.” Or of President Obama’s argument that, as a result of a federal bailout, the auto industry is now “leading the way” toward a type of economic growth that benefits middle-class Americans (Miller Reference Miller2015; Patterson Reference Patterson2013).

Similarly, scholars attempting to project economic growth often focus on transportation innovation. Techno-optimists like Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee point to innovations like self-driving cars and drones and predict rates of growth on par with the Industrial Revolution (Brynjolfsson and McAfee Reference Brynjolfsson and McAfee2014, 1–12). Skeptics like Robert Gordon argue that growth has been slow since 1970 and will continue to be so based on their assessment of the likely effects of the same technologies (Gordon Reference Gordon2014).

But transportation innovation does not create economic growth in the same way as innovation in other sectors.2 For the most part, people do not directly consume the benefits of innovative transportation technology, nor is its direct use a major factor in determining whether businesses can produce goods more cheaply or more efficiently. Most of the benefits of transportation innovation do not come from faster and easier travel to existing homes, offices, and businesses.

Instead, transportation innovations allow us to move our homes, offices, factories, and stores into more pleasing and efficient patterns. Early automobiles, for example, were not much more effective than streetcars or even horses at navigating the crowded and pockmarked streets of dense, urban cores (Foster Reference Foster1981, 9–24; Norton Reference Norton2011). But cars allowed people and firms to spread outward across a region, creating new opportunities for suburban life, particularly following substantial public investment in roads designed for automobiles (Mohl and Biles Reference Mohl and Biles2012, 204–06). Likewise, the elevator, on its own, would not have provided many benefits to residents of cities; elevators are not that much better than stairs in existing low-rise buildings.3 But elevators make the use of taller buildings possible, increasing a city’s capacity for density. While transportation innovations provide some benefits to people making their existing commutes, the bulk of the economic gains from transportation innovations comes from changes in patterns of land use.

Transportation scholars have long known that infrastructure investments both depend on current land use patterns and spur changes in those patterns. There is a massive literature built around what are known as Land Use Transport Interaction (LUTI) models, which analyze the complex interrelationship between infrastructure investments, land use, and transportation developments (Van Wee Reference Van Wee2015; Wegener Reference Wegener, Fischer and Nijkamp2014).

But the scholars and practitioners in the field (and their increasingly complex software) almost entirely ignore the ubiquity of legal limitations on land use. In comprehensively planned cities, market forces do not, on their own, determine the flow of benefits to the broader economy from transportation innovations or investments. If one wants to know how a road or light rail line will affect land uses in a comprehensively regulated city or region, one must understand both the content of zoning and other regulations – rules governing what can be built, where, and how it can be used – and the politics of changing these regulations. New housing, for instance, will not simply emerge around new highways or rail lines. Governments must allow the market to work by revising zoning and subdivision ordinances that accommodate construction.

The same logic applies to new transportation technologies. The kinds and amounts of gains from advances in transportation technology depend heavily on how land use law reacts (or, sometimes, overreacts) to their presence.

This chapter will assess how well modern land use law has or might accommodate three major recent or soon-to-arrive transportation innovations: (1) global positioning systems (GPS), mobile mapping, and real-time traffic information services (like Google Maps, Apple Maps, TomTom, Garmin, and Waze); (2) e-hailing apps for taxis, shared rides, and shuttles (like Uber, Lyft, and their competitors);4 and (3) still-developing self-driving autonomous cars.

These technological innovations should allow two separate types of changes to land use patterns.

First, they will allow what I will call “distributed density” within urban areas. Each technology should allow for more overall density in cities. To varying degrees, they make travel through dense areas easier, allow for more efficient use of existing infrastructure, and reduce the costs of congestion (and need for parking spaces) for a given density of people and businesses. Further, the advantages of these developments do not depend on extreme density. Nodes of heavy density (e.g., stores along a high street, or apartments within a quarter of a mile of a train station) may spread a bit further outward without losing the gains of agglomeration. Regions will maximize the economic gains from these technologies if they allow dense and diverse development – if buyers can choose townhouses or apartments in towers.

Second, the innovations will allow development to spread around cities, as they – particularly GPS and potentially autonomous cars – reduce the costs of traveling substantial distances, both in time and in effort (Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Kalra, Stanley, Sorenson, Samaras and Oluwatola2014).

But modern land use law does not equally allow both of these types of development. Land use law and politics are particularly ill-equipped to produce distributed density. Its deep procedural rules and the multiple ways current residents can block new construction make incremental housing growth particularly difficult (Hills and Schleicher Reference Hills and Schleicher2011, 81–89). While massive new projects sometimes can run the gauntlet of the zoning amendment process, environmental review and Not In My Backyard (NIMBY) political opposition, developers and homeowners proposing incremental changes in existing neighborhoods often cannot afford the lawyers and lobbyists necessary to do so (Platt Reference Platt2004, 317–20).

These limitations on “distributed density” precede transportation innovations like Uber and GPS. Housing advocates have started discussing the “missing middle” of the housing market – townhouses, two-tops, triple deckers, etc. – that flourished before modern zoning rules, but that are now almost impossible to construct (Hurley Reference Hurley2016; Schleicher Reference Schleicher2013). Similarly, U.S. land use regulations excessively keep retail out of residential zones, separating land uses more than any other advanced economy (Hirt Reference Hirt2013). Finally, and most pressingly, land use regulations substantially harm the regional and national economies by limiting overall density in many rich regions and cities, a trend that really took off in the 1970s and 1980s, as Bill Fischel details in Chapter 1 of this volume (Hsieh and Moretti Reference Hsieh and Moretti2015; Schleicher Reference Schleicher2013). In contrast, the fringes of metropolitan areas are less regulated, so these transportation innovations should allow our metropolitan areas to spread further.

This leads to two basic predictions. In downtowns and heavily zoned metropolitan areas, the land usages that zoning regulations allow will fall even shorter of what is economically ideal. Today’s urban and inner-ring suburban zoning politics will undercut future opportunities to restructure housing and retail. Innovations in transportation will increase the cost of our dysfunctional land use law regime. Further, land use law will hinder further transportation innovation. The incentive to develop, say, autonomous taxis will be lower in less dense cities. If we hope to maximize the gains from transportation innovation and avoid biasing future technology innovations,5 we must reform land use regimes, particularly in the richest metropolitan areas.

2.1 An Introduction to Transportation and Agglomeration Economies

To discuss new transportation technologies, I lay out a simple model of how transportation technologies interact with land usage generally. This section will discuss (a) the interaction between transportation technology and urban economic activity, and (b) how the study of the economic effect of zoning on regional economies can tell us how to study the economic impact of transportation technologies.

2.1.A Transportation Technologies and Agglomeration Economies

All analyses of urban economies start with the same basic question: why do people and firms move to cities? (Glaeser Reference Glaeser2008a). Economists usually describe three basic types of “agglomeration economies,” or gains from density (Marshall Reference Marshall1890; Schleicher Reference Schleicher2010, 1517–28).

The first kind of agglomeration economies deal with shipping costs for goods. Intermediate goods manufacturers can save on shipping costs by moving closer to one another. Much of the history of American urban development turns on decisions by firms to reduce shipping costs by moving to cities (Glaeser and Kohlhase Reference Glaeser and Kohlhase2004, 198–99; Glaeser and Ponzetto 2007). Almost every major urban center in the United States developed around a major port or rail transport hub. As innovative transportation technologies (like the combustion engine or the shipping container) have driven transportation costs downward, though, manufacturing firms have less and less reason to move to urban areas (Schleicher Reference Schleicher2013, 1551–52). Other factors better explain modern urbanization.

The second major category of agglomeration economies includes the benefits of deep markets. Workers in a particular metropolitan region can often participate in a deeper labor market (Rodriguez and Schleicher Reference Rodriguez and Schleicher2012, 640–47). Think of actors moving to Los Angeles. They can specialize (perhaps becoming an expert in one type of role), match more easily (find a studio that needs their specialty), invest in human capital development (acting school or private lessons), and insure themselves against firm-specific risk. These benefits do not accrue to similarly talented workers in rural areas or regions with less labor market depth.

Further, transportation technologies and infrastructure define the depth of a given labor market. Workers must be able to reach employers in order to work for them, a point clear to those who advocate that we give cars to the poor to increase their labor market opportunities (Logan and Molotch Reference Logan and Molotch1987, 262).

Depth matters in markets besides labor and in areas smaller than metropolitan ones, too. Retail markets benefit from market depth. Perhaps the most traditional form of retail development is the “high street,” where various stores cluster along a single strip. By locating along one strip instead of spreading out through a neighborhood, stores can specialize (Schleicher Reference Schleicher2010, 1522). Consider, for example, a stretch of restaurants and bars. They form “restaurant rows” because consumers can go to the street knowing that there will be lots of different options and that, if one place is too crowded, another place will have seats (Rodriguez and Schleicher Reference Rodriguez and Schleicher2012).

The third big category of agglomeration benefits is information spillovers. People learn from others, and so population density leads to more productive workers. As Alfred Marshall famously noted, in cities, “the mysteries of the trade become no mystery but are, as it were, in the air” (Reference Marshall1890). Software developers and entrepreneurs move to Silicon Valley for more than just the deep labor markets and the California sun; they move to learn from other tech people over coffee or drinks (Rodriguez and Schleicher Reference Rodriguez and Schleicher2012, 651). Indeed, those who move to urban areas see faster wage growth as a result of learning (Glaeser and Mare Reference Glaeser and Mare2001; Rodriguez and Schleicher Reference Rodriguez and Schleicher2012). Patent applications are much more likely to cite other research done in the same place (Jaffee 1993). Chance interactions between residents provide such substantial benefits that firms sometimes design their office space to generate “random” encounters. When Steve Jobs was at Pixar, he placed bathrooms in a central location in order to get different kinds of people to run into one another (Silverman Reference Silverman2013).

The key insight for this chapter is that people move to cities because being close to other people provides economic and social benefits that offset the higher costs for property (and congestion) in cities.6 As Edward Glaeser notes, “conceptually, a city is just the absence of space between people and firms” (Reference Glaeser2008b, 4). This “absence of space between people” is not mere physical space, but rather the ease of communal interaction, either intentionally or by chance. Two people on different sides of a wall are physically proximate, but will find it difficult to interact.7 Similarly, cultural differences can make even physically proximate people quite distant.

The central factors that translate proximity into interactions are the ease of travel and information. Before the invention of the automobile, people living in what are now suburbs of major cities could not participate in regional labor markets. Land that was quite physically proximate to downtown was used for low-intensity purposes like farming because there was no easy way to commute (Mohl and Biles Reference Mohl and Biles2012, 204–05). Only those places attached to downtown by omnibuses and streetcars developed into suburbs, because they made commuting and thus participation in urban labor markets possible (Mohl and Biles Reference Mohl and Biles2012, 87–88). Information plays a similar role. On high streets, for example, stores benefit from colocation because shoppers can easily see nearby retailers. A physically close shop on a side street would not capture agglomeration benefits from being part of a deep market, since shoppers would never see it or know about it.

Urban economic models have always relied heavily on transportation costs to explain land use patterns. Starting with Von Thunen and going through Alonso and Mills in the 1970s, economists developed “mono-centric models” assuming that business would be done in the city center (Glaeser Reference Glaeser2008a, 15–17; Schleicher Reference Schleicher2010, 1516–17). Distance from the city center predicted the kind of economic activity of the land, be it farmland or housing; the longer it took to travel downtown, the less intense the land usage. Trade theorists like Masahira Fujita, Paul Krugman, and Tony Venables use shipping costs to predict where firms will locate (Fujita, Krugman, and Venables Reference Fujita, Krugman and Venables1999; Krugman Reference Krugman1995). Transportation technologies determine urban fates.

This is true across types of agglomeration economies. The depth and quality of urban labor markets turn on the quality of urban transportation networks. Alain Bertaud writes: “The potential economic advantages of large cities are reaped only if workers, consumers, and suppliers are able to exchange labor, goods, and ideas with minimum friction and to multiply face-to-face contacts with minimum time commitments and cost. The productivity of a city with a growing population can increase only if travel between residential areas and firms and among firms’ locations remains fast and cheap” (Bertaud Reference Bertaud2014, 7; Reference Bertaud2004). Studies across countries show that worker productivity correlates with the number of jobs reachable within 20 minutes and 60 minutes (Bertaud Reference Bertaud2014, 10). Labor market depth depends on both housing density and ease of transportation.

Further, patterns of development are highly dependent on transportation technologies. As mentioned previously, suburbs developed first around horse-drawn omnibus stops, then near electric streetcar stops; most of these developments were within walking distance from the commuter stops (Foster Reference Foster1981, 18–20; McShane and Tarr Reference McShane and Tarr2007). Cities, for good and ill, invested heavily in remaking streets for automobile traffic. These investments created much more distributed development across metropolitan regions (Foster Reference Foster1981, 10). The automobile now allows suburban residents to participate in regional labor markets without paying for expensive urban real estate.

Of course, many people want to live in urban areas and are willing to make tradeoffs against housing prices (per square foot) to do so. And labor markets are not purely regional. People who work heavy-hour, high-pay jobs in finance, law, and technology frequently want to live in cities and do not want to commute, meaning firms have incentives to do so (Edlund, Machado, and Syiatschi Reference Edlund, Machado and Syiatschi2015). And cities retain many agglomerative advantages due to information spillovers and market depth in other areas, from retail to dating markets. But the rise of the car is associated with spreading out in all directions around urban areas.

Implicit in this well-known insight that the car enabled “sprawl” lies an important concept. Descriptive accounts of transportation innovation must integrate land use. The importance of a new road or rail line depends on how this new infrastructure will change demand for homes and offices, and how, in turn, those changes will affect the use of the infrastructure.

All (good) modern transportation planning focuses on the endogeneity of land uses and transportation. Land Use Transport Interaction (LUTI) models study the effect of new transportation infrastructure on traffic and land usage (Aditjandra Reference Aditjandra2013; Wegener Reference Wegener2013). These studies recognize that causality points in all directions. To address these difficulties, these models have become unbelievably sophisticated, built around “activity-based and agent-based or microsimulation models working with high-resolution parcel or grid-cell data” and individualized to particular urban areas, making them costly and requiring lots of data and computing power (Wegener Reference Wegener2013).