12.1 Introduction

Real estate is vulnerable to procyclicality, with real estate booms and busts often leading to financial and economic instability.1 The Great Recession in the United States was triggered by the collapse of securitized finance, which had spawned a credit-fueled bubble in residential real estate (Levitin and Wachter Reference Levitin and Wachter2012; McCoy et al. Reference McCoy, Pavlov and Wachter2009). The bursting of the twin real estate and credit bubbles ultimately crippled the U.S. financial system and the real economy (Levitin, Pavlov, and Wachter Reference Levitin, Pavlov and Wachter2012; Levitin and Wachter Reference Levitin and Wachter2012).

In hindsight, we know that securitization was accompanied by a decline in underwriting standards that exacerbated the subsequent economic downturn and that contractual obligations in the form of representations and warranties did not deter this decline. Through securitization, originators pass virtually all mortgage risk to the market. Thus, in order to align the incentives of originators with those of investors in residential mortgage-backed securities (RMBS), originators are subject to put-back risk for violations of representations and warranties. The purpose of these contractual obligations is to assure maintenance of underwriting standards.

This chapter examines why representations and warranties failed to accomplish this key requirement for the integrity and sustainability of the securitization process. These provisions in loan sale agreements for RMBS are paradoxical in nature. Representations and warranties did not stop the wave of bad loans from capsizing the U.S. housing market in 2007 and 2008 and the expectation that they would, arguably, worsened the crisis. Yet more recently, liability for the breach of those representations by originators and other securitization participants, along with loan losses themselves, have been linked to bank lenders’ withdrawal from the market and overly tight lending standards, which slowed the recovery process. Post-crisis, lenders’ fears over put-back exposure appear to have contributed to a contraction in lending to creditworthy borrowers.2 This contraction has coincided with the return of thinly capitalized nonbank lenders, who have little capital at risk for future mortgage repurchase claims.

If both are true, then the representations and warranties in securitization documents through 2008 were simultaneously too weak and too harsh, engendering procyclicality.3 During the run-up to the 2008 financial crisis, these representations gave investors false assurance that mortgage loans were being properly underwritten, contributing to overinvestment in underpriced MBS. Moreover, there was virtually no enforcement of those provisions during the bubble, which exaggerated their cyclical effects. Only later, after the harm was done, did the pendulum swing to excess enforcement and fear of penalties, which encouraged undue restrictiveness in the origination of mortgages and hampered the economic recovery.

Is this paradoxical outcome due to surprise that these agreements would ever be enforced and surprise about how they were enforced; or due to the unforeseen events that made these agreements actionable; or due to misaligned incentives that led agents to knowingly ignore these contractual obligations? Or to some combination of these differing interpretations of ignorance or malfeasance? More critically, going forward, for the integrity of the securitization process, can representations and warranties be reformed to buttress the integrity of the securitization process, or are there intrinsic limitations on the use of contractual terms to assure this outcome?

This chapter proceeds as follows. Part 2 provides an overview, describing the intended role of representations and warranties in deterring loose underwriting and providing compensation for breach, how these contractual provisions failed to halt the deterioration in underwriting during the credit bubble, and the efforts to enforce these provisions following the 2008 crisis. In Part 3, we survey the market responses to put-back litigation, including contraction of credit by bank lenders and the concomitant surge in market share by more lightly regulated nonbank lenders, and propose reforms. In particular, we contend that representations and warranties will not have teeth unless they are accompanied by countercyclical provisioning and capital standards. Part 4 concludes.

12.2 Historical Background and Overview of Recent Mortgage Put-Back Liability

The current controversy over mortgage put-backs emanates from the shift of U.S. housing finance from a bank-based system to a capital-markets system over the past 50 years. Fifty years ago, mortgage originators usually held loans in portfolio. But that all changed in the 1970s with the invention of MBS,4 which gave mortgage lenders the ability to move newly originated mortgages off their balance sheets by bundling those loans into bonds sold to private investors. Over time, securitization became the predominant means of mortgage finance and three securitization channels emerged: Ginnie Mae for FHA-insured and VA mortgages, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac for other conforming mortgages (also known as agency mortgages), and the private-label (Wall Street) market for nonconforming mortgages (most notably jumbo loans and subprime and Alt-A mortgages).5 Securitization offers benefits to depository institutions by solving the term-mismatch problem arising because bank liabilities (in the form of demand deposits) are considerably more liquid than their long-term mortgage assets (Diamond Reference Diamond2007).

12.2.A The Growth of Mortgage Securitization

The secondary market in the United States, established after the Great Depression, was small, relative to the overall mortgage market until the 1980s. Originators, mostly savings and loan associations (S&Ls), held mortgages in portfolio, other than government-insured Federal Housing Administration (FHA) and Veterans Administration (VA) mortgages. In the aftermath of the S&L crisis, Ginnie Mae and the government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs), Fannie and Freddie, grew rapidly as funding sources (Levitin and Wachter Reference Levitin and Wachter2013a, 1165–67).

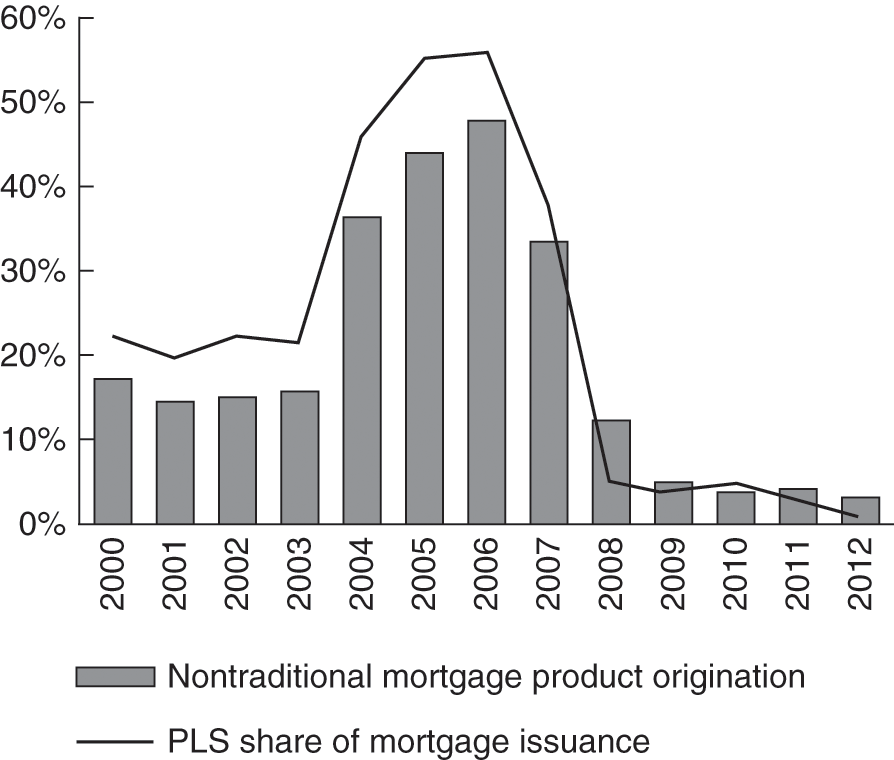

Starting in the late 1990s and accelerating between 2003 and 2007, regulatory shifts (McCoy et al. Reference McCoy, Pavlov and Wachter2009) and changes to the structure of the mortgage chain led to the onset of a secondary mortgage lending regime dominated by private-label securitization and mediated by Wall Street investment banks (Levitin and Wachter Reference Levitin and Wachter2012; Wachter Reference Wachter2014). A substantial expansion of credit followed. The number of purchase mortgages originated increased from 4.3 million to 5.7 million and remained above 5.5 million through 2006 (FFIEC 2015). Private-label securities (PLS) had originally funded jumbo mortgages whose size precluded their inclusion in GSE securitizations. The PLS lending of 2003 through 2007 funded nontraditional mortgage (NTM) products and subprime loans. Prior to the PLS boom, most mortgages were conforming, self-amortizing 30-year fixed-rate mortgages (FRMs). However, during the boom, there was a substantial increase in nontraditional mortgages, including non-amortizing (or negative amortization) balloon, interest-only (IO), and option-payment mortgage products, as well as subprime loans and other Alt-A products (which did not require full documentation of income). The market share of NTMs in dollars (including second-lien mortgages) rose from 20 percent in 2003 to 50 percent in 2006 (Figure 12.1). There was a simultaneous change in the types of products sold in the secondary market and a shift to private-label securitization.

Figure 12.1 Market Share in Dollars of Nontraditional Mortgage Products and Private Label Securitization, 2000–2012

Note: Nontraditional mortgage products are subprime, Alt-A, and home equity loans.

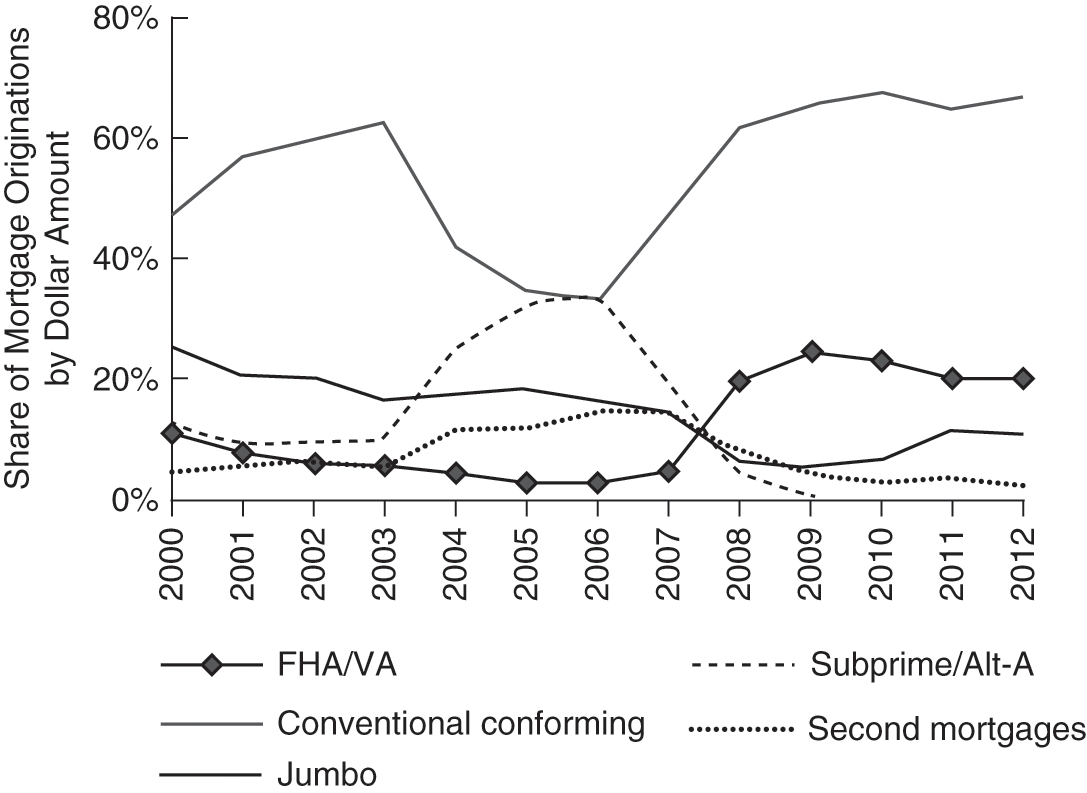

While most conforming mortgages were securitized by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, most NTMs and subprime loans were securitized in the PLS market. Figures 12.1 and 12.2 (which disaggregate mortgages by type) show the share of PLS and NTM and subprime mortgage issuance peaking during 2006 and almost disappearing after 2008. While the PLS market share rose during the housing boom, the GSE (conventional, conforming) and Ginnie Mae markets shares shrank (Wachter Reference Wachter2014).

Figure 12.2 Origination Shares by Mortgage Type, 2000–2012

12.2.B Principal-Agent Problems in Securitization

Securitization ushered in new principal-agent problems that the inventors of MBS worked to address. Adverse selection was one issue, consisting of the fear that originators would retain their best loans and securitize the rest. Investors were also concerned about information asymmetries, because lenders know more about the quality of the loans they originate than investors and have incentives to conceal negative information when selling those loans.6

Private capital would shun the mortgage finance system absent assurances to investors on both scores. Consequently, securitizers used a host of techniques to address the principal-agent problems in securitization, including disclosures, underwriting standards, quality control, due diligence reviews, and risk retention. Key among those techniques was representations and warranties, the focus of this chapter.

12.2.C The Use of Representations and Warranties in MBS

Every mortgage-backed securitization starts out with the sale of a pool of mortgage loans by a seller to a purchaser. The purchaser is generally a GSE, an FHA/VA securitization issuer, or an investment bank that plans to transfer the loans to a special purpose vehicle for bundling into MBS for sale to investors. Often the seller is the originator, but it can also be a large bank that aggregates loans bought from a third-party originator. In the course of the series of transfers that make up a securitization, many of the transferors make representations and warranties to the next transferee down the chain (Murphy Reference Murphy2012).

The central contract governing the loan sale is a Mortgage Loan Purchase Agreement between the seller and the purchaser (Miller Reference Miller2014, 259, 267). This agreement or its equivalents are found in all three major securitization channels, including Ginnie Mae, the GSEs, and private-label securitizations (FHFA 2012, 6, 10–12). The typical agreement contains more than 50 representations, warranties, and covenants by the seller to the purchaser (see, e.g., Master Loan Purchase Agreement 2005, § 5 & Exh. A). The representations and warranties inure to the benefit of the purchaser and sometimes to its assignees, transferees, or designees, including the trustee of the securitization trust (see, e.g., id., § 6).

While these representations and warranties share common subject matters, in PLS transactions their precise language varies (sometimes significantly) across deals (Standard & Poor’s 2013b; Tate 2016). In contrast, representations and warranties are standardized for GSE and Ginnie Mae securities. The representations and warranties made to Fannie and Freddie are cheaper to litigate by virtue of their standardization and are also generally stronger than those agreed to in private-label deals (Fleming Reference Fleming2013; Strubel Reference Strubel2011).

Representations and warranties serve dual functions: deterrence and compensation. One reason investors demand those representations is to deter lax loan underwriting by lenders. Investors also require those provisions to assure compensation in the event of breach. For this reason, the enforcement provisions of the Mortgage Loan Purchase Agreement require repurchase of any mortgages that are found to be in breach.

12.2.C.1 The Contractual Representations and Warranties

Some representations and warranties deal with the legal status, bona fides, operating systems, and condition of the seller and related parties (see, e.g., Master Loan Purchase Agreement 2005, § 5(b) & Exh. A), but most involve statements about the legality and quality of the loans being sold. The loan-specific representations and warranties can be grouped into the following subjects (see, e.g., id., Exh. A; Miller Reference Miller2014, 270–73):

Mortgage Loans as Described: Under this provision, the seller affirms that information relating to the mortgage loans in the pool is complete, true, and correct and the interest rates are those stated in the mortgage notes. A related provision states that all necessary documents have been delivered to the custodian and that the seller possesses the complete, true, and accurate mortgage file.

Current Payment Status: In this representation and warranty, the seller confirms that no loan in the pool is in default or has been delinquent for 30 days or more in the past 12 months. In addition, a warranty provides a safeguard against early payment default by stating that the first three monthly payments shall be made within the month in which each payment is due. In a related, open-ended provision, the seller confirms that it has no knowledge of any circumstances or conditions that would cause any of the mortgage loans to become delinquent.

Legality: Representations and warranties typically provide that each mortgage loan when it was made complied in all material respects with applicable local, state, and federal laws, including, but not limited to, all applicable predatory and abusive lending laws. In addition, the seller warrants that none of the mortgage loans were “high cost” or predatory loans for purposes of federal or state or local anti-predatory lending laws. A companion provision states that the origination, servicing, and collection practices used with respect to the mortgage loans are legal and in accordance with accepted practices.

Appraised Value: Another group of representations and warranties provides that the properties securing the mortgage loans have been appraised according to the standards specified in the Mortgage Loan Purchase Agreement.

No Misrepresentations: This provision states that no one has engaged in any misrepresentation, negligence, fraud, or similar occurrence with respect to a mortgage loan.

Loans Meet Agreed-Upon Underwriting Standards: In this set of provisions, the seller confirms that the mortgage loans in the pool all meet specified underwriting standards, including maximum loan-to-value ratios and minimum credit scores.

Loans Meet Agreed-Upon Loan Features: In these provisions, the seller agrees that none of the loans in the pool contains prohibited features. This list of prohibited features varies with the loan pool, but sometimes includes balloon terms, negative amortization, shared appreciation, prepayment penalties, mandatory arbitration clauses, and/or single premium credit insurance terms.

Mortgage Loan Fully Marketable and Enforceable: These representations and warranties provide assurance that the mortgage loans are fully marketable and enforceable and have not been impaired, waived, or modified.

No Outstanding Charges: Here the seller states that all taxes, assessments, insurance premiums, and other charges due under the terms of the mortgages have been paid and are up to date.

Underlying Properties Intact and Adequately Insured: In this representation and warranty, the seller confirms that all of the properties securing the mortgage loans are undamaged and have adequate hazard insurance, including flood insurance where required, as well as title insurance.

Conforming Asset Class: This representation and warranty states that all of the mortgaged properties securing the loan pool belong to the appropriate asset class (e.g., residential properties instead of commercial properties).

Owner-Occupied: The seller affirms that all of the homes securing the loans are owner-occupied.

Provisions Regarding the Timing, Amount, and Crediting of Payments: Several other representations and warranties address the timing, amount, and crediting of payments.

Taken together, these representations and warranties allocate the responsibility for loan quality to the originator or other seller, who can ensure that quality more cheaply than the purchaser (Miller Reference Miller2014, 263, 286–88, 290).

Despite the wealth of representations and warranties, most put-back requests and disputes turn on a handful of core representations (271–73). These representations include statements that the loans in the pool: (1) are as described (particularly with respect to loan-to-value ratios, credit scores, debt-to-income ratios, owner-occupied status, and the like); (2) have no past delinquencies and will not go delinquent within the first three months after origination; (3) are free from misrepresentations; (4) are legal; and (5) conform with the agreed-upon underwriting standards. In addition, some repurchase requests are prompted by claims of inflated or fraudulent appraisals.

12.2.C.2 Enforcement Provisions for Representations and Warranties

The standard Mortgage Loan Purchase Agreement limits the contractual relief for breach of these representations and warranties to one set of remedies and one set alone7 (Miller Reference Miller2014, 274–76). Under the “Repurchase Obligation” provisions in versions of the Agreement before the crisis, if the substance of any representation and warranty was inaccurate and the inaccuracy materially and adversely affected the value of the mortgage loan in question or the interest of the purchaser, then the representation and warranty was breached, even if the seller was unaware and could not have been aware of the inaccuracy when the representation was made (see, e.g., Master Loan Purchase Agreement 2005, § 6). The Agreements go on to state that following prompt written notice of the discovery of such an inaccuracy, the seller shall use its best efforts to promptly cure the breach within 90 days. If the breach cannot be cured, then the seller, at the purchaser’s option, shall repurchase the mortgage loan at issue at the purchase price8 (see, e.g., id., § 6). Effectively, this gives the purchaser a put option for loans that violate representations and warranties.

In theory, this put option is quite strong. This remedy is not technically conditioned on a realized loss to the investor; instead, it can apply so long as a breach results in a material paper loss to the mortgage loan in question. As a practical matter, however, operationally relatively “small” errors in representations would not in general lead to exercise of the put option prior to default. In default, such errors become salient. And in the crisis, the decline in real estate prices made such ordinarily ignored errors particularly salient as prices and collateral declined dramatically.

At the same time, the contractual remedy for breach of representations and warranties is only as good as a seller’s solvency. For the put option to have bite, a seller must still be operating and have sufficient assets to pay a judgment. This became a particular concern in the case of breaches by nonbank lenders, more than 100 of whom operated with razor-thin margins and capsized after they lost their funding in 2007.9

12.2.D The Mortgage Crisis

Had investors given representations and warranties scant credence when they originally bought loans, those provisions might not have mattered. However, investors took representations and warranties seriously. The rating agencies, for instance, touted their review of the representations and warranties for every private-label deal in order to give investors confidence that their ratings had integrity (see, e.g., S&P Global Ratings 2004). After the crisis, the Basel Committee and government investigators concluded that investors had placed undue faith in the efficacy of representations and warranties (Basel Committee on Banking Supervision 2011; Ergungor Reference Ergungor2008).

To investors’ chagrin, those representations and warranties failed to prevent the spike in mortgage loan defaults that culminated in the 2008 financial crisis. As discussed earlier, by the early 2000s, private-label securitization had outgrown its traditional function of funding jumbo conforming loans to also financing increasing numbers of nontraditional mortgage products. From 2004 through 2007, investors flocked to subprime and Alt-A MBS because of their higher yields (McCoy et al. Reference McCoy, Pavlov and Wachter2009, 496–97 and fig. 1). Originators met the demand for higher coupon mortgages with risky interest-only and pay-option mortgages with no or negative amortization, which together reached an astonishing 50 percent of all mortgage originations in spring 2005 (id., 497, fig. 1). A series of decisions by federal banking regulators to deregulate residential mortgages also helped pave the way for this unprecedented growth (Engel and McCoy Reference Engel and McCoy2011, 151–205).

During the run-up to the crisis, the proliferation of subprime and Alt-A loans was accompanied by a marked deterioration in loan underwriting standards. Between 2002 and 2006, two of the strongest predictors of default rose noticeably: loan-to-value ratios and the proportion of loans with combined loan-to-value ratios of more than 80 percent (Levitin and Wachter Reference Levitin and Wachter2015). Meanwhile, lenders increasingly layered one risk on top of another, often combining low-equity, no-amortization loans with reduced documentation underwriting (McCoy et al. Reference McCoy, Pavlov and Wachter2009, 504–05 and fig. 3). Loan fraud also became more prevalent during this period, with private-label securitized mortgages and low-documentation mortgages experiencing particularly high levels of fraud (Mian and Sufi Reference Mian and Sufi2015). Loan origination volume shifted to lenders who used private-label securitization with lower and less well-enforced underwriting standards, although there is evidence that there was somewhat of a decline in the GSE underwriting standards as well (Wachter Reference Wachter2014, Reference Wachter, Wachter and Tracy2016). Under pressure to maintain market share, other lenders cast aside their reputational concerns and lowered their lending standards in response (Engel and McCoy Reference Engel and McCoy2011, 38–40).

As the ensuing disaster unfolded, it soon became apparent that representations and warranties had not prevented the sharp deterioration in underwriting standards during the credit bubble. Increasingly, it became apparent that loan features and performance that were in direct breach of the representations and warranties – including excessive loan-to-value ratios, early payment defaults, and outright fraud – had become commonplace. The first warning signs of higher defaults appeared in subprime and Alt-A adjustable-rate mortgages (ARMs) beginning in mid-2005 and worsened after that (see Table 12.1). As defaults mounted in 2006, the number of mortgage repurchase requests remained modest but started to increase in response10 (Sabry and Schopflocher Reference Sabry and Schopflocher2007). According to Fitch Ratings, early payment defaults were the “root cause” of these early repurchase requests, particularly in loans with layered risks such as lower credit scores, second liens, and stated income underwriting (Fitch 2006).

Table 12.1: Percentage of Subprime and Alt-A Adjustable Rate Mortgages (ARMs) 90 Days or More Past Due or in Foreclosure

| Reporting Period | Subprime ARMs | Alt-A ARMs |

|---|---|---|

| July 2005 | 5.63% | 0.43% |

| July 2006 | 8.16% | 0.74% |

| July 2007 | 14.63% | 3.06% |

| December 2007 | 20% | 6% |

Through 2006, rising housing values allowed troubled borrowers to refinance their mortgages in order to avoid default. In the first quarter of 2007, however, housing prices began to slide nationwide for the first time since the Great Depression and the foreclosure crisis began in earnest. During this period, the compensatory and deterrent functions of representations and warranties were seriously tested.

12.2.E Repurchase Demands and Actions to Enforce Put-Back Clauses

As falling home prices impeded the ability of distressed borrowers to avoid default by refinancing their loans or selling their homes, mortgage delinquencies skyrocketed and mortgage put-back requests surged (Hartman-Glaser et al. 2014, 28, fig. 3). Data on aggregate recoveries for all put-back demands are hard to come by. But we can get a sense of the magnitude by examining put-back collections by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

The two GSEs sought recourse for bad loans for two lines of business activities. First, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac lodged repurchase claims against originators or aggregators for defective loans that had been sold to them. While the evidence is incomplete, the percentage of loans subject to Fannie/Freddie buyback claims seems to have been modest (less than 2 percent of balances at origination for GSE 30-year, fixed-rate full-documentation, fully amortizing loans from select deals) (Goodman and Zhu Reference Goodman and Zhu2013; Goodman et al. Reference Goodman, Parrott and Zhu2015, 3–5 and fig. 1). From January 1, 2009 through the third quarter of 2015, as a result of those claims, Fannie and Freddie collected a total of $76.1 billion from more than 3,000 companies for loans repurchased from their mortgage-backed securitization trusts (GSE Repurchase Activity). This more than doubled the total industry liability that Standard & Poor’s had originally estimated for GSE repurchase and securitization claims in 2011 (Murphy Reference Murphy2012). Not all of the GSEs’ put-back claims were successful, however, and the two enterprises ultimately withdrew or stopped pursuing another $61.9 billion in repurchase demands (GSE Repurchase Activity). For the put-back claims that settled, the average payment per loan was substantially less than the average purchase price for all of the loans11 (Siegel and Stein Reference Siegel and Stein2015).

In addition, Fannie and Freddie pursued claims for their purchases of private-label MBS during the housing bubble (Hill Reference Hill2011/2012, 375–81). In January 2016, their regulator and conservator, the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA), reported that it had settled lawsuits against 16 out of 18 financial institutions involving the sale of private-label instruments to Fannie and Freddie. Technically, these were not buyback claims insofar as the actions alleged securities law violations and sometimes fraud in the sale of the PLS. But these claims were also founded on lax mortgages and their financial effect on originators and issuers was similar. Total settlement amounts equaled $18.2 billion as of year-end 2014 (FHFA 2016b).

12.2.E.1 Sources of Put-Back Claims

As this discussion of GSE recoveries suggests, each of the three securitization channels has generated put-back demands and lawsuits (Standard & Poor’s 2013a). While these demands share many similarities across channels, there are also differences depending on the channel.

Turning to the private-label channel, many private-label issuances featured long chains of transfers involving mortgage brokers, loan originators, correspondent or wholesale lenders, investment banks, depositors, trustees, and investors. At each link in the securitization chain, representations and warranties were often made. Consequently, put-back demands for any given securitization in the PLS channel usually involved not just one, but a sequence of repurchase requests throughout the chain12 (Hill Reference Hill2011/2012, 375; Murphy Reference Murphy2012). Private-label securities were especially prone to buyback claims because they experienced higher average default rates than GSE RMBS (Fitch 2011).

As discussed, the GSE channel also generated repurchase claims. Although the GSEs’ issuances performed better on average than their PLS cousins, as noted previously, the representations and warranties made to Fannie and Freddie were stronger in nature and spawned more interpretive case law due to their standardization, making them easier to litigate successfully (Fleming Reference Fleming2013; Strubel Reference Strubel2011).

Finally, defective FHA-insured loans generated their own set of buyback and statutory claims, sometimes by Ginnie Mae and sometimes by the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ). Some of those claims became turbocharged due to certifications that the originators had to sign when making FHA-insured loans. Under the FHA’s direct endorsement program, designated lenders are allowed to designate mortgages as eligible for FHA insurance. In order to qualify for this program, lenders must provide annual certifications that their quality control systems comport with all relevant rules of the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD)13 (Goodman Reference Goodman2015). Lenders must further certify that each FHA-insured loan observes all relevant HUD rules14 (id.). Before 2015, lenders had to make these affirmations regardless of their knowledge or their ability to detect violations (id.).

The DOJ has taken the position that any lender who knowingly submits loans for FHA mortgage insurance containing material underwriting defects that disqualify those loans for FHA mortgage insurance makes a false claim for purposes of the False Claims Act (U.S. Department of Justice 2016). Under that Act, lenders who knowingly submit false or fraudulent claims to the federal government for payment or approval are liable to the government for damages. Justice Department claims under the False Claims Act pose the highest monetary exposure of any of these types of claims because violators must pay civil penalties of $5,000 to $11,000 per claim plus treble damages. In 2011, the United States sued all of the top five mortgage originators for False Claim Act violations in connection with their certifications for FHA insurance15 (Goodman Reference Goodman2015). According to the Justice Department, the federal government recovered more than $5 billion in these and other claims for housing and mortgage fraud from January 2009 through October 2015 (U.S. Department of Justice 2015).

In addition, the DOJ has also pursued Federal Housing Administration claims under the powerful and flexible civil money penalty provisions in Section 951 of the Financial Institutions Reform, Recovery and Enforcement Act of 1989 (FIRREA) (Standard & Poor’s 2013a). FIRREA is attractive in many circumstances because it has a longer limitations period and lower threshold of proof than the False Claims Act. However, the Second Circuit Court of Appeals cast doubt on the viability of this theory when it ruled in 2016 that FIRREA precludes recovery for intentional breach of contractual representations and warranties through the sale of poor-quality mortgages absent evidence that a seller intended to defraud purchasers when the representations and warranties originally were made (United States ex rel. Edward O’Donnell 2016).

12.2.E.2 Success of Put-Back Claims

As the GSE experience shows, buyback claims have not been invariably successful. The chances of prevailing on claims for breach of representations and warranties vary widely according to the type of breach, the passage of time, the litigation capacity of the plaintiff, and the solvency of the defendant.

To begin with, success may turn on the type of claim. Some breaches of representations and warranties are easily proven because they turn on commonly available evidence using objective standards. Early payment defaults are a good example, because servicing records normally show whether the borrower was delinquent in the first three months of the loan.

Other breaches are harder to substantiate and subject to dispute. The facts may require further investigation into hard-to-obtain documents outside of the purchaser’s possession or the representation in question may be couched in vague or subjective language. Thus, cases alleging false loan-to-value ratios or appraised values require reconstructing the actual appraised value at origination, which is subject to debate and difficult to do. Purchasers who assert other types of fraud or misrepresentation generally must prove those claims based on evidence from the face of the loan or deal documents, which can be daunting (Miller Reference Miller2014, 300–01). Buyback disputes over loans that supposedly were allowed to depart from underwriting standards due to compensating factors can be particularly messy to litigate.

While it is relatively simple to point to errors in loan documents based on a sample of the contested book of business, the import of those errors will be in question. Were they simple errors (such as whether the borrower was self-employed versus a contractual employee) that would not or should not be counted against the originator? Or is a large share of such errors indicative of sloppy underwriting that should and does matter to outcomes in conjunction with a price decline, even though it is the price decline itself that is a major factor in default and thus in losses?

In addition, the amount of time that has elapsed since the loan sale affects the deterrent role of representations and warranties and the prospects for compensation. Many Mortgage Loan Purchase Agreements predating the crisis contained no hard-and-fast outer time limits on bringing put-back claims. Under those contractual provisions, and absent an otherwise binding statute of limitations, a purchaser could ostensibly demand repurchase at any time upon discovery of a breach of a representation until the loan principal was fully repaid (Hartman-Glaser et al. 2014; Miller Reference Miller2014, 311; Tate 2016). This is not a hypothetical concern: Hartman-Glaser and colleagues (2014, 2 n. 2) discovered loans from GSE securitizations going back to 1985 that were the subject of repurchase requests between 2011 and 2014. In too many cases, defects did not surface and repurchase claims were not made until those responsible were long gone, eviscerating the deterrent function of representations and warranties.

This timing issue is a double-edged sword for purchasers and sellers. The more time that elapses until a put-back demand is made, the harder it is for the purchaser to prove due to dimming memories, missing witnesses, and lost documentation (Miller Reference Miller2014, 299–300). At the same time, the specter of open-ended contingent liabilities can erode investors’ confidence in a bank or other issuer. For this reason, sellers have aggressively resisted older put-back claims based on lack of reasonably prompt notice16 or expiration of statutes of limitations (id.).

The litigation capacity of the purchaser also affects the likelihood of successful put-back claims. The vigor with which the GSEs pursued buyback demands reflected their ability to terminate lenders’ contractual rights to sell agency loans (Hill Reference Hill2011/2012, 371),17 their greater litigation might combined with that of the federal government, plus the mission of Fannie and Freddie’s conservator to maximize the assets in the conservatorship estates in many cases. Similarly, Ginnie Mae’s ability to pursue claims through civil actions brought by the Justice Department – together with the threat of treble damages under the False Claims Act – substantially enhanced its power to negotiate favorable settlements.

In contrast, investors found it harder to bring successful put-back claims for private-label securities. One hurdle is that representations and warranties for PLS are less standardized than those for agency MBS (Fleming Reference Fleming2013; Standard & Poor’s 2013a, 6). In addition, in order to have standing, at least 25 percent of an issue’s shares must first typically vote to demand that the securitization trustee pursue a put-back claim. Only if the trustee fails to take action within a set period of time may investors directly sue. Still, investor groups have managed to surmount this obstacle (Murphy Reference Murphy2012; Standard & Poor’s 2013a, 6).

Finally, as noted before, recovery depends on the seller’s continued solvency. The largest banks survived years of repurchase claims bruised but intact (Standard & Poor’s 2013a, 3, 7–8). However, other mortgage originators failed due in part to high put-back demands (Barr Reference Barr2007; New Century Bankruptcy Court Examiner 2008, 36, 70–72, 105–06, 405–06), leaving some of those demands unsatisfied.

12.3 Market Responses and Policy Implications

There have been two major market responses to the post-crisis impact of put-backs. First, citing the need to avoid future put-backs (Lux and Greene Reference Lux and Greene2015, 17, 24), major lenders – particularly well-capitalized lenders who have much to lose in the event of future put-back claims – have either withdrawn from government-insured lending or have imposed on themselves credit overlays that go beyond the requirements of the GSEs, thereby lowering their market share.18 Second, nonbank lenders have emerged as the major origination channel to fill this gap. The shift is dramatic.

The problems with these market responses are twofold. First, the shift to thinly capitalized entities implies that, in a future crisis, representation and warranty penalties could not be effectively enforced against those entities. This undermines the compensatory value of representations and warranties going forward, as well as deterrence.

Second, lenders who believe they are no longer assured of default insurance through FHA and the GSEs are imposing credit overlays that go beyond the levels required by FHA and the GSEs. These lending constraints go beyond historic levels and beyond the levels historically associated with creditworthy lending, with mortgage market and home lending consequences that are described later.

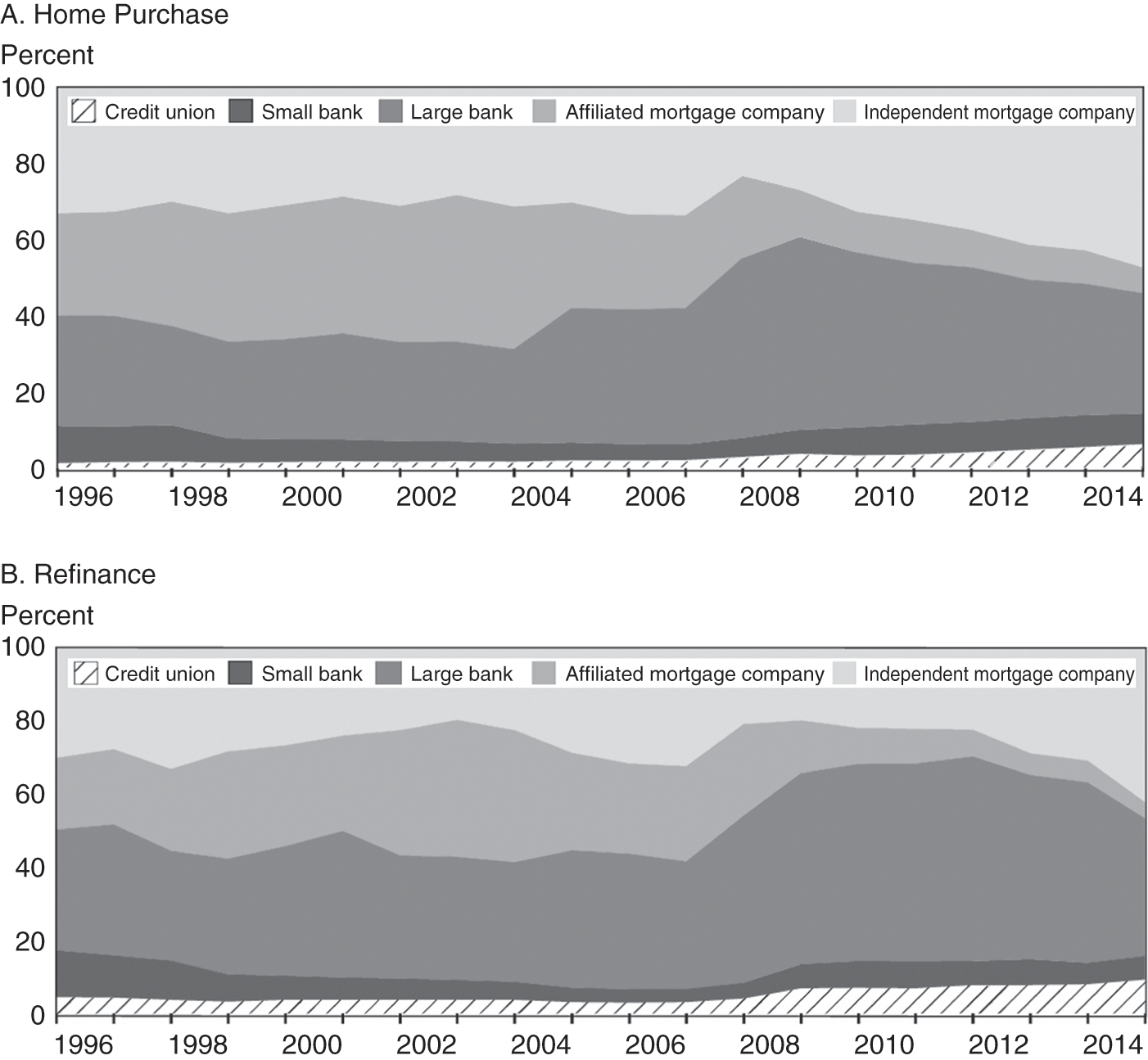

12.3.A The Shift to Thinly Capitalized Entities, Growth of Credit Overlays, and Consequences

Immediately after the crisis, most home mortgages were originated by the major banks that were subject to capital adequacy and repurchase reserve requirements. More recently, however, the market share of mortgage originations by banks and especially the largest banks has fallen substantially (see Figure 12.3).19 This void has been filled by more thinly capitalized nonbank mortgage originators who are not regulated by prudential banking regulators for solvency (Lux and Greene Reference Lux and Greene2015), renewing concerns about the financial capacity of those lenders to make good on their representations and warranties.

Figure 12.3 Market Share by Lender Type, 1995–2014

The lack of willingness on the part of established, traditional banks to extend mortgage credit has created an opportunity for a new type of market participant: minimally capitalized nonbank mortgage lenders. These lenders are denoted in Figure 12.3 as independent mortgage companies. In view of the recent history of successful repurchase litigation against banks, nonbank lenders enjoy a distinct competitive advantage because they lack legacy put-back exposure and have scant capital at risk for future repurchase claims. The growth of these institutions (Standard & Poor’s 2014) presents unique systemic risk – as these lenders are not subject to traditional capital requirements under prudential bank regulation and are minimally capitalized,20 their failure can be harmful to the market as a whole (FHFA OIG 2014b, 23–24; FSOC 2015, 10, 114). There is no evidence, moreover, that investors are demanding pricing differentials based on the capital adequacy of individual sellers (Standard & Poor’s 2013a).

At the same time, imposition of credit overlays by bank lenders who believe they are no longer assured of default insurance through FHA and the GSEs has resulted in a mortgage market that is notably constrained. This market constraint may be explained in part from regulatory pressures from HUD and DOJ. Although the primary intent of HUD and DOJ enforcement is compliance with HUD rules, it has prompted FHA’s largest bank lenders to announce that they are significantly reducing their extension of mortgage credit in response (Goodman Reference Goodman2015). As Goodman states, “lenders have begun to protect themselves the only way available to them: credit overlays, risk-based pricing, or a general pull away from FHA lending” (id.).

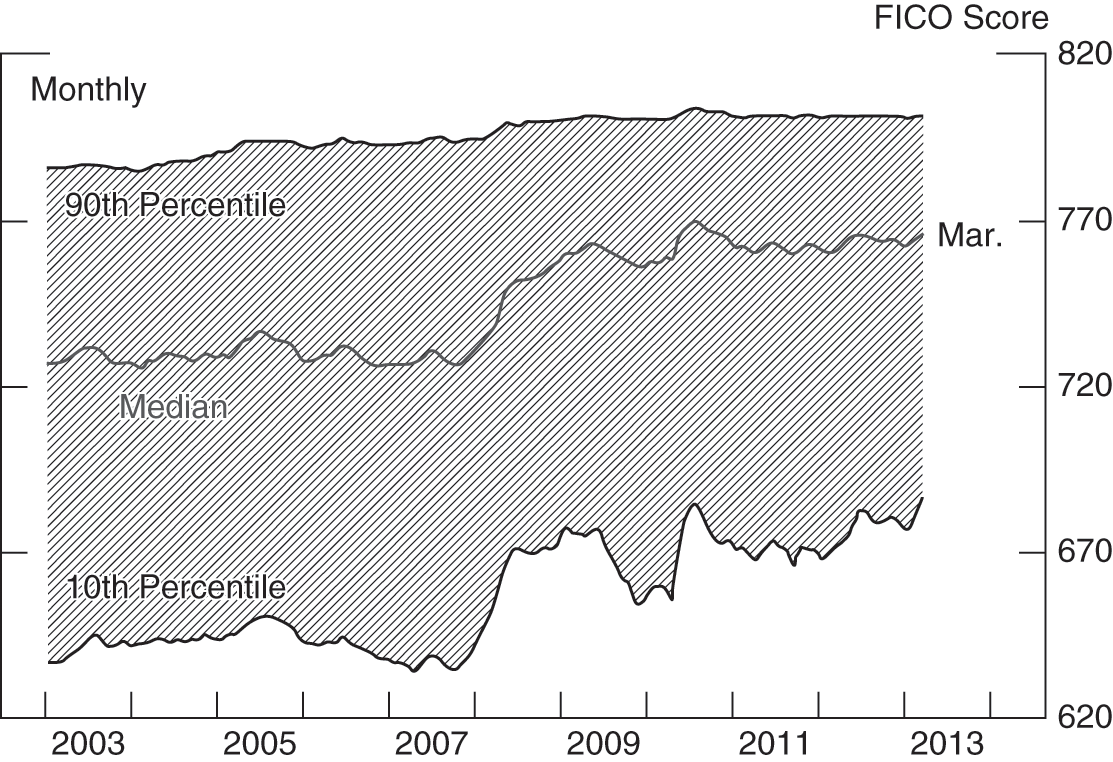

As evidence of the role of buyback requests on mortgage underwriting standards, Hartman-Glaser and colleagues (2014) show that the change in the probability of buyback requests on GSE MBS explains tighter mortgage lending standards. Figure 12.4 demonstrates the tightening of standards for FICO scores.

Figure 12.4 FICO Credit Scores on New Prime Purchase Mortgages from 2003 to 2013

The housing market has certainly made a recovery since the financial crisis, with housing starts having doubled since the recession. However, these heightened constraints on mortgage credit continue to suppress demand for housing and homeownership21 (Zandi and Parrott Reference Zandi and Parrott2014). In an analysis of the extent to which constrained credit has affected the mortgage market, Bai and colleagues (Reference Bai, Goodman and Zhu2016) found that 5.2 million more residential mortgages would have been made between 2009 and 2014 if credit standards had been at levels similar to those in 2001.

The tightening of the availability of credit has implications for homeownership. Acolin and colleagues (Reference Acolin, Bricker, Calem and Wachter2016a) estimate the role of the tightening of credit on the aggregate homeownership rate. They find that the homeownership rate in 2010–2013 is predicted to be 5.2 percentage points lower than it would be if borrowing constraints were at the 2004–2007 level and 2.3 percentage points lower than if the constraints were at the 2001 level, before the relaxation of credit took place (Acolin et al. Reference Acolin, Bricker, Calem and Wachter2016b, 13).

This tightening in lending standards is part of a cycle in lending. During the credit expansion leading up to 2008, representations and warranties contributed to the overheating of the cycle by giving false assurance to investors while failing to deter the race to the bottom in lending standards. Years later, the protracted enforcement of representations and warranties slowed recovery from the crisis by impeding access to mortgages for creditworthy borrowers. This history of under-correction during the bubble and over-correction following the collapse is the hallmark of procyclicality.

This procyclicality has micro- and macro-prudential repercussions as well as serious distributive implications. The after-the-fact use of representations and warranties as a means to allocate risk presented solvency threats to individual entities as well as having macro repercussions, by increasing systemic risk and slowing recovery. The distributive implications of the unnecessarily tight credit box on low- and moderate-income households and people of color persist.

Accordingly, the goal of reforms to representations and warranties should be to reverse the procyclicality that is inherent in the current system. To achieve this, it will be necessary to right-size the enforcement of these provisions while endowing them with deterrent effect. Doing so will enhance financial stability while expanding the credit box in a healthy and sustainable way going forward.

12.3.B Procedural Reforms

One way to increase the efficacy of representations and warranties is to counter the long temporal disconnect between breaches of those representations and enforcement. In many cases, the perpetrators of those breaches were long gone by the time repurchase claims were made. Shortening the timespan between the sale of loans and the presentation of put-back claims will enhance deterrence while speeding up recovery.

After the financial crisis, the put-back process was slow to initiate in many cases and arduously protracted afterward, thus prolonging the threat of litigation. In part, this could be blamed on resistance to put-back claims by sellers. However, purchasers contributed to the drawn-out nature of the proceedings by dragging their feet in presenting claims. The GSEs, for instance, did not close out their repurchase claims on loans originated before 2009 until the end of 2013, and only then at the insistence of FHFA’s then acting director, Edward DeMarco (Goodman et al. Reference Goodman, Parrott and Zhu2015, 7).

The GSEs, FHFA, and other actors eventually instituted a variety of reforms to speed up the put-back process. The GSEs instituted sunset provisions to bring some finality to the put-back process for performing loans.22 In addition, some court decisions hold that statutes of limitation on buyback claims run from the date of sale, not the date of discovery (Miller Reference Miller2014, 290, 312), putting the onus on purchasers to make claims more promptly.

Another concern is the vague and open-ended nature of some of the representations and warranties on which sellers are sued. In private-label deals, sellers had latitude to renegotiate the language of the representations and warranties they agreed to, thus potentially undermining their capacity to deter. Their negotiating ability was substantially less in deals with the GSEs and Ginnie Mae.

There will always be tension about the advisability of objective representations versus ones that are more general and ambiguous. Sellers want certainty about compliance and the extent of their exposure; purchasers worry about losses from negligence, fraud, and misconduct that they cannot anticipate in advance. A problem, as discussed further later, is that a breach may be “minor.” In the nature of underwriting it may be difficult to avoid such mistakes completely. Then in the aftermath of a crisis, all such mistakes may be grist for put-back claims. But how to tell which claims are important and which are not? While this tension will likely never fully be resolved, the following principles can be used to cabin the open-ended nature of certain representations and warranties:

First, the industry should adopt improved procedures to expedite the negotiations over put-back claims. Sellers have complained that purchasers insist on repurchase even when loans go delinquent due to life events such as job loss and divorce following origination (Standard & Poor’s 2013b). It goes without saying, however, that sellers should not be responsible for events such as these outside of their control unless breach of a representation or warranty exacerbated the loss severity or risk of default. To resolve these and similar repurchase disputes without resort to litigation, sellers and purchasers could agree to send those disputes to neutral third-party arbitration. The GSEs adopted this independent dispute resolution procedure in 2016 (FHFA 2016a; Standard & Poor’s 2016) and Ginnie Mae and private-label conduits might follow suit.

Second, loans that consistently perform for a stated number of years should be exempt from repurchase claims. The GSEs’ sunset provisions embody this approach by shielding loans with a 36-month record of on-time payments (12 months in the case of HARP loans) from buyback demands (FHFA OIG 2014a, 15–17; Goodman et al. Reference Goodman, Parrott and Zhu2015, 3).

Third, liability for breach should be excused where the seller was not aware of the problem and could not have discovered it using reasonable investigation. HUD revised its annual certification in this respect in 2015 by adding the language “to the best of my knowledge and after conducting a reasonable investigation” (Goodman Reference Goodman2015).

It would be also advisable to standardize representations and warranties as much as possible in the private-label market. Doing so would promote the growth of arbitral decisions and case law interpreting those standardized terms, which could then provide guidance for faster resolution of similar disputes in the future.

Similarly, it is time to confront the fact that False Claims Act treble damages sanctions are overkill in the absence of knowing fraud. The threat of treble damages is discouraging bank lenders from serving the low- and moderate-income community that FHA loans were designed to serve. Instead, penalties for flaws in FHA loans should be tailored to the FHA’s defect taxonomy, according to the seriousness of the violation and the violator’s culpability (Goodman Reference Goodman2015; HUD 2014).

In an ideal world, the deterrent effect of representations and warranties could also be strengthened on the front end to curb the proliferation of lax loans during credit booms while obviating the need for enforcement. Suggested reforms have included improved due diligence and internal quality control, stronger data integrity controls for automated underwriting systems, faster post-purchase reviews by investors, and improved, standardized disclosures for put-back obligations (which the Securities and Exchange Commission issued in 2014 (Dodd Frank Act § 943; SEC 2014)).

All of these reforms, in place or contemplated, have a potential flaw, however, which is that they rely on originators’ compliance. Standardized disclosures and detailed underwriting guidelines are only as good as the integrity of the underwriting process that generates them. Even if some purchasers carefully monitor loan originations through pre-purchase and post-purchase quality assurance and control as suggested, there is the potential for other purchasers to not do so, thus undermining the quality of underwriting for the system as a whole. Those originators and purchasers who skirt requirements and procedures in the “hustle” for business will rapidly gain market share, even as they lower their costs. The result will be higher prices as loans are made that otherwise would not be made and the higher prices will mask the poor underwriting. The representations and warranties may stop some, but if more aggressive lenders operate in this way, there is an “externality” (Wachter Reference Wachter2014) that results as the quality of the aggregate mortgage book of business deteriorates and risk increases even for more careful lenders. Moreover those lenders who are willing to undermine standards will set the bar lower for other lenders who unless they similarly lower the bar will not be able to attract the marginal borrower (Pavlov and Wachter Reference Pavlov and Wachter2006). And the process is unleashed again.

12.3.C Systemic Reforms

Lenders have called for greater clarity in the representations and warranties that they provide. But better drafting alone is not the answer to deterrence. The events of 2008 showed that lenders ignored even objective representations and warranties such as loan-to-value caps in the rush for greater market share at the height of the credit bubble. The market incentives are for contractual representations and warranties to be procyclically implemented. No one will exercise a put option when prices are rising, but everyone will do so once they have fallen. Besides market forces that lead to sliding standards across firms during the bubble, in the aftermath, there will be competitive tightening: firms will not want to be the lax lender when they fear that representations and warranties will be strictly enforced. While a normal level of “mistakes” is to be expected and not entirely avoidable, such mistakes will become the potential source for put-backs if in the overall market, prices have plummeted due to the aftermath of the unsustainable expansion of credit. And at that point put-backs bite. Accordingly, stronger external measures are needed in order for representations and warranties to have real teeth, to prevent market-wide pressures for deterioration in underwriting. Some of those measures are already in place.

Ability-to-Repay and Qualified Mortgage Provisions: The new ability-to-repay and qualified mortgage rule promulgated by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau places a federal floor under underwriting practices by prohibiting reduced documentation loans. Because the rule requires documentation and verification of income and assets, it should significantly reduce one of the main sources of put-back claims. In addition, the rule creates a new category of loans with especially risky features such as balloon terms and negative amortization – called non-qualified mortgages – and imposes liability for any such loans made in disregard of the borrowers’ ability to repay (CFPB 2013; Dodd-Frank Act §§ 1411–1412). The rule is enforced through federal examinations of lenders and through public and private enforcement mechanisms (which apply to poorly underwritten loans and non-qualified mortgages), which should help ensure that the federal floor is observed (Dodd-Frank Act §§ 1024(a)(1)(A), 1025–26, 1042(a), 1413, 1416(b)).

Heightened Solvency Safeguards: Increased solvency supports would give lenders a greater stake in observing representations and warranties ex ante in order to avoid liability for breach ex post, while providing purchasers with greater assurance of compensation where needed. These supports can take the form of capital requirements, provisioning thresholds, and mandatory risk retention.

To begin with, countercyclical provisioning requirements for representations and warranties would give representations and warranties more teeth while ensuring that the reserves on hand for compensation by lenders are sufficiently deep. Currently, insured depository institutions maintain reserves against their representation and warranty exposures. However, the computation of those reserves is severely procyclical. Because institutions compute these reserves based on losses already incurred, instead of expected future losses (FASB 2016, 1; Standard & Poor’s 2013a, 6), they chronically under-reserve for representation and warranty liability during expansions, while struggling to boost those reserves post-crisis once lawsuits spike.

A shift to the countercyclical technique known as dynamic provisioning would reverse this perverse sequence of events. During credit booms, dynamic provisioning triggers a switch in the algorithm for loss reserves that calculates those reserves as if credit were contracting. Later, if an economic downturn strikes, that switch is turned off (Caprio Reference Caprio2009, 22; Ren Reference Ren2011, 11–19). This model requires lenders to build up their representations and warranties reserves during credit booms, when they have cash, and allows them to spend down those reserves during economic downturns to pay for any legal exposures. To the extent that these added reserves made representations and warranties more effective, any resulting legal liability would be reduced.23

While federal regulators have not adopted dynamic provisioning, U.S. accounting standards have made strides toward countercyclical provisioning. In 2016, the Financial Standards Accounting Board adopted a new standard requiring lenders to calculate their loan loss allowances based on expected credit losses, regardless of whether losses have probably been incurred (FASB 2016, 1–2; see Board of Governors et al. 2016a). The provision, which takes effect in 2019, requires lenders to book all projected losses over the lifetime of the loans immediately upon origination. This is not a fully countercyclical approach because some losses for long-term residential mortgages may not become expected until years down the road. Nevertheless, the new provision will require lenders to incorporate forecasts of future conditions in addition to past and current events and record projected losses up front. Importantly, the new FASB provision applies to all bank and nonbank lenders alike.

Minimum capital requirements form another important solvency safeguard. Under Basel III, prudential banking regulators substantially increased the capital adequacy requirements for residential mortgages originated and securitized by federally insured depository institutions.24 In addition, Basel III imposes a countercyclical capital buffer designed to kick in when credit conditions start to overheat (Department of the Treasury et al. 2013, 62031, 62171). While questions surround the implementation and efficacy of the countercyclical capital buffer if left to regulators’ discretion (McCoy Reference McCoy2015, 1204–05 and n. 118), Basel III takes a step in the right direction by increasing the deterrence exerted by representations and warranties during incipient credit bubbles.

In the capital arena, however, regulatory arbitrage remains a serious concern. Federal banking regulators lack jurisdiction to impose minimum capital requirements on independent nonbank lenders (Board of Governors et al. 2016b, 37).25 Even if they did have jurisdiction, uniform capital standards would be highly unlikely, given federal regulators’ conclusion that Basel III is incompatible with the business models of some large nonbank mortgage servicers (id., 37–39). This means that as the nonbank sector grows, it will continue to enjoy arbitrage opportunities and escape the disciplining effect of uniform capital requirements. Not only will this reduce the in terrorem effect of representations and warranties, it will perpetuate competitive inequalities among bank and nonbank lenders. Unless Congress empowers federal banking regulators to impose capital adequacy requirements on mortgage lenders regardless of charter, it will be incumbent on the GSEs, Ginnie Mae, and the private-label sector to demand more meaningful safeguards from nonbank originators than they have so far.26 Whether these investors will impose sufficient capital requirements during a credit boom, when nonbank originators are likely to expand and investors are prone to over-optimism, is questionable. Moreover if investors and private-label securitizers themselves, in a bid to grow market share, fail to demand comparable safeguards from nonbank originators, the game will be on again. We can already see potential warning signs of trouble in the rising numbers of FHA mortgages being made by nonbank lenders to borrowers with FICO scores below 660 (Lux and Greene Reference Lux and Greene2015, 18–25).

12.4 Conclusion

During the run-up to the 2008 financial crisis, representations and warranties (contractual statements enforceable through legal action) on lending processes may have given investors false assurance that mortgage loans were being properly underwritten. This assurance in turn may have contributed to overinvestment in MBS in two ways. First, the assumption that legally enforceable penalties associated with representations and warranties would deter lax underwriting may have led to less screening of loans than would otherwise have occurred. In turn, the failure to oversee actual underwriting practices enabled the spread of lax lending practices. The existence of these representations and warranties and the potential penalties associated with them did not deter lax underwriting. Paradoxically, after the fact when the representations and warranties were enforced, this enforcement coincided with a tightening of credit beyond historic norms, with serious distributive implications. Post-crisis, lenders’ fears over put-back exposure appear to have caused them to scale back, particularly on government lending to creditworthy borrowers. The representations and warranties as used in mortgage lending in the run-up to the crisis were part of the procyclicality of lending, both in the easing and tightening phases of the lending cycle.

We suggest reforms to add to the deterrent value of representations and warranties. Particularly we suggest a shift to the countercyclical technique known as dynamic provisioning to increase the in terrorem effect of representations and warranties. This model requires lenders to build up their representations and warranties reserves during credit booms, when they have cash and when risk is growing, and allows them to spend down those reserves during economic downturns to pay for any legal exposures. To the extent that these added reserves signaled greater risk, they would make self-enforcement of representations and warranties more effective and procyclicality would be reduced. We also propose stricter capital standards.

Nonetheless, such changes would be useless unless they were adopted throughout the lending industry: otherwise, just those entities with risky practices would increase their market share. And next time such entities are more likely to be thinly capitalized, as the lesson of capital exposure to legal risk has been learned, thus further reducing the deterrence effect of representations and warranties, going forward.

Authors’ Note

Our thanks to Lee Anne Fennell, Benjamin Keys, Karen Pence, and the other participants at the conference sponsored by the Kreisman Initiative on Housing Law and Policy at the University of Chicago in June 2016 for their helpful comments.