2 Exporting the Revolution Why Only Some Eastern EU New Democracies Support Democratization Abroad

Why is it that some new eastern EU democracies, such as Poland, the Czech Republic, and Slovakia, have become noteworthy democracy promoters in the postcommunist space, while other new democracies, such as Slovenia and Bulgaria, have invested little in supporting democracy abroad? In general, why is it that only some countries that recently experienced regime change emerge as diffusion entrepreneurs that support similar change abroad?

The chapter finds that some of the same eastern EU civic activists who prepared the democratic breakthroughs in their country subsequently also argued in favor of their state promoting democracy abroad as well. Where these democracy promotion entrepreneurs represented strong advocacy contingents, namely, large and united movements that articulated resonant arguments, their states incorporated democracy promotion into their foreign policy. In sum, the stronger the eastern EU civic movements in favor of democracy promotion, the more attention their governments have paid to this issue.

This chapter theorizes an understudied mechanism underlying regime change waves – the purposeful efforts of states that recently experienced regime change to support similar change abroad. Explaining why some new democracies support democracy abroad more actively than others has both theoretical and empirical implications. This issue sits at the intersection of the debates about the international impact of revolutions, about the foreign policy of democracy promotion, and about the mechanisms underlying diffusion processes and waves of regime change. In answering why only some new democracies support democratization abroad, this chapter also sheds light on three other related and previously unanswered questions: (1) why certain states that recently experienced revolutionary regime change engage in the export of their revolutions (despite its high costs and low chances of success); (2) why some new democracies that used to be recipients of democracy assistance become democracy promoters; and (3) why certain countries that are adopters of diffusion practices (or norm takers) become their exporters (or norm makers). Furthermore, this chapter answers these questions through the prism of the diffusion of democracy – a process that has been crucial in the making of the modern world and the liberal international order that organizes it.

The Puzzle: Only Some New Democracies Emerge as Democracy Promoters

The third wave of democratization, like most other revolutionary waves, included a number of revolutions that served as models for emulation and learning by other countries and for export by entrepreneurs committed to the promotion of similar regime change abroad. In fact, the third wave of democratization unfolded in part because a number of new democracies sought not only to “observe the principles of democracy and human rights at home but also to propagate them elsewhere.”1 Much like Western support for democracy abroad,2 the democracy promotion commitments of new democracies have often been inconsistent, ad hoc, and of low priority.3 Nevertheless, these new democracies have played an important role in the diffusion of democracy around the globe as demonstrated by a number of quantitative studies that document “neighbor effects” on regime change and a few qualitative/historical studies that document that these effects are in part the result of purposeful democracy-promotion efforts of newly democratic states.4

As Chapter 1 discussed, however, there are significant differences in the democracy promotion activism of new democracies. A Freedom House survey examining the foreign policies of forty countries worldwide over a ten-year period (1992–2002) documents that a number of new democracies have made a “strong effort” to support “the ideals of democracy” abroad, while other new democracies have promoted democracy only passively.5 According to the study, for the period covered, in Latin America, Argentina, Chile, and Brazil have been more engaged in democracy promotion than have Peru or Mexico; in Africa, Botswana, Ghana, and Senegal have been much more active than have South Africa, Mali, or Benin; and in Asia, South Korea has been more involved in supporting democracy abroad than have Thailand or the Philippines.

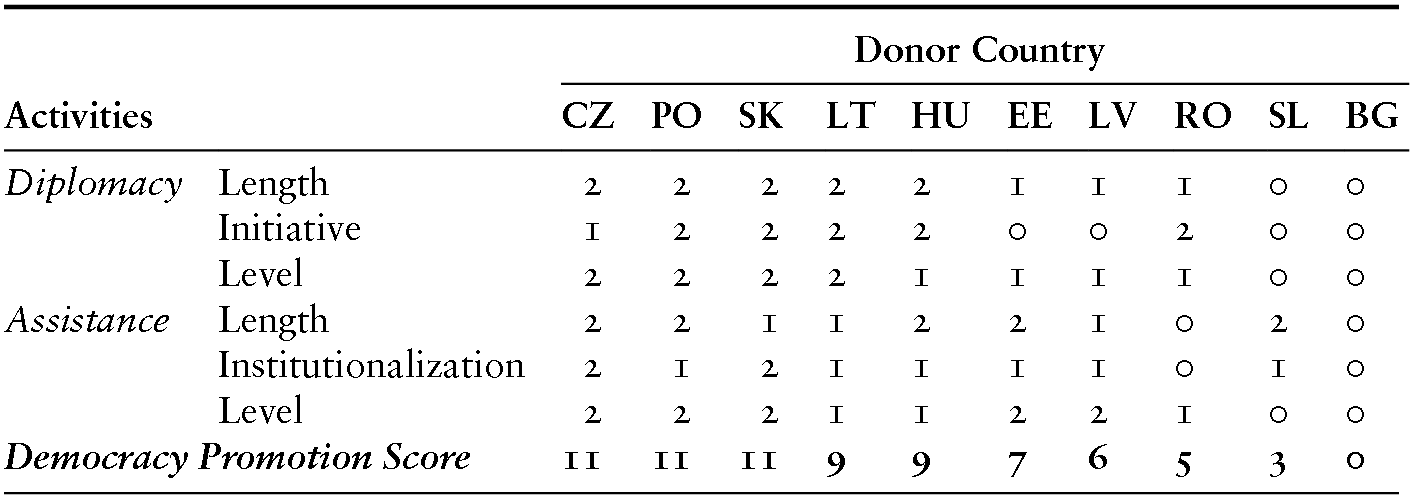

Similarly, there are important differences among the eastern EU members in terms of the length, level, and initiative of their democracy promotion activities. [These differences are summarized in Table 2.1. The table is based on a review of the foreign-policy record of and the aid provided by the eastern EU states. The use of diplomacy and aid is assessed according to three criteria: length, level, and institutionalization/initiative, measured on a low-medium-high (or 0–1–2 respectively) scale. All scores were validated in interviews with knowledgeable observers of eastern EU democracy promotion. For a detailed explanation of the table, see Appendix 2.1.]

Table 2.1. Eastern EU Democracy Promotion Activism by Donor Country

Among the eastern EU democracy promoters, countries such as Bulgaria, Slovenia, and Romania have been slow to transition from democracy promotion recipients to providers support for democracy abroad. Bulgaria has neither taken diplomatic initiative nor supplied democracy assistance. Slovenia has provided very little democracy aid and has supported the democratization of its neighbors primarily indirectly through advocating for their European integration. Romania has taken some diplomatic initiative both bilaterally and multilaterally but has made only minimal investments in these initiatives and Romania’s democracy assistance has primarily consisted of earmarked funds to international organizations.

In contrast, other eastern EU countries such as the Czech Republic, Poland, and Slovakia have quickly become key democracy promotion players in the former Soviet Union and the western Balkans. Within a year of their own democratic breakthroughs, Poland and Slovakia began providing diplomatic support for the democratization of a few of their neighbors. Poland has enjoyed considerable success in spearheading EU democracy promotion in its neighbors to the east. Slovakia, meanwhile, has become one of the main agents of European policy toward the western Balkans and, more recently, Belarus. The Czech Republic began promoting democracy within five years of its independence and has done so very actively both regionally and globally, especially by taking diplomatic initiative multilaterally. The Czech Republic has set up the only dedicated eastern EU Transition Promotion agency and has emerged as a defender of beleaguered prodemocratic oppositions around the globe, specializing in Belarus and Cuba and, to a lesser extent, in Burma and Iraq. The Czech Republic, Poland, and Slovakia give the most democracy assistance of all eastern EU donors as measured by the share that democracy assistance represents in the overall official development assistance provided by each of those three countries. Poland and the Czech Republic were also among the first donors in the region, and the Czech Republic and Slovakia have, respectively, the first and second most institutionalized systems for the provision of democracy assistance.

Hungary, Lithuania, Estonia, and Latvia rank in between the least and the most active eastern EU democracy promoters. Budapest and Vilnius began providing diplomatic support for the democratization of their neighborhood early on and have taken both bilateral and multilateral initiative. Unlike Lithuania, which has been an active democracy promoter and the home of the Belarusian opposition in exile, Hungary’s investment in regional democratization beyond the protection of minority rights and cross-border cooperation has remained limited. Estonia and Latvia, on the other hand, started promoting democracy diplomatically mostly after their EU accession and have done so moderately and without taking initiative. The institutionalization of the democracy aid distribution in all these countries is relatively weak, and the democracy assistance provided by all but Estonia has been either belated or small.

Theorizing Revolution Export: Why Do Only Some New Democracies Promote Democracy?

What explains the differing levels of democracy promotion among the new eastern EU democracies? The answer to this question sits at the intersection of the study of revolution, diffusion, and democracy promotion. Most of the diffusion literature, however, has a structural bias or is adopter centric6 – that is, it has overlooked the transformation of certain adopters of diffusion practices into promoters of the same practices. Similarly, in the democracy promotion literature, the transition of new democracies from recipients to suppliers of democracy support has not been explained. Work on the factors shaping the foreign policy of revolutionary states, however, has identified three families of such influences: (1) revolutionary ideology and identity, (2) domestic pressure, and (3) balance of power or of threat.7 Policy observers of eastern EU democracy promotion have offered a number of parallel explanations of the varying levels of activism of these countries – their commitment to democracy; civic advocacy; and pressure by regional and global actors, namely, the EU, the United States, and Russia. In other words, for a given revolutionary country, how do the revolutionary change itself, the domestic politics in its wake, and the country’s international environment contribute to the emergence of that country as a revolution exporter?

Identity: Normative Commitment and Signaling

Some argue that revolution is exported when it is prescribed by the revolution’s ideology and universal aspirations.8 On assuming power, the revolutionaries acquire the opportunity to embed their ideology in foreign policy as it comes to guide – whenever possible – the domestic as well as the international affairs of the revolutionary state. Pleas from aspiring revolutionaries abroad, seeking assistance or a successful model for their own country, could strengthen a revolutionary state’s perceived obligation to export the revolution’s ideals.9 Some have argued that the leaders of the Bolshevik revolution, for example, were “convinced that it was both possible and obligatory for the revolutionary regime to do all it could to promote revolution on a world stage.”10 Cuba also demonstrated a “strong belief in the necessity for international revolution and a willingness at times to let this belief override more immediate and obvious interests.”11 Proponents of the democratic peace proposition have similarly claimed that democracies tend to externalize their domestic values.12

Policy observers of eastern EU democracy promotion have suggested that as new democracies, these countries are sensitive to violations of democracy abroad.13 Indeed, eastern EU diplomats regularly emphasize the liberal values their countries share with new and established democracies and at times express “solidarity” with other countries struggling for democracy and human rights. For instance, in 2005, a number of prominent eastern EU politicians condemned the violations of human rights and democracy in Cuba in an open letter stating, “Given how central the values of human rights, democracy and the rule of law are in Europe, we feel it is our obligation to speak out against such injustices continuing unchecked [in Cuba]. . . . Cuba’s regime has remained in power, the same ways that communist governments did [. . . in Eastern Europe] – by using propaganda, censorship, and violence to create a climate of fear.”14 Consider also the Czech foreign ministry’s explanation for the establishment of its Transition Promotion unit: “The Czech Republic advocates the principles of human solidarity and accepts its share of responsibility for resolving global problems. To that end, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs created a new department, charged with the task of assisting in the transition to democracy wherever necessary.”15

There are, however, meaningful differences in the extent to which the eastern EU leaderships have internalized the various democratic norms and practices. In the eastern EU states where the domestic commitment to democracy is relatively weak, these norms are unlikely to guide the foreign policy of these states or to be exported abroad.

Therefore, to the extent that new democracies externalize their domestic values, the stronger the domestic commitment to the democracy, the more active this state’s democracy-export efforts.16

An alternative identity-based argument proposes that it is exactly recent “converts,” with a (still) weak or feigned commitment to the revolution that export its ideals in the short term, possibly creating a long-term tradition. These states might respond to increased rewards associated with embracing the revolution’s ideology and promote it abroad to signal their commitment to these values.17 These rewards can be moral, such as increased legitimacy or a desired reputation, or material, such as access to preferential treatment, aid, trade, or other resources. In other words, states that are not committed to democracy at home might nonetheless engage in democracy promotion as a way of obtaining moral or material benefits.

Demonstrating commitment to the revolution’s ideals, can be difficult and costly. Violations of a norm or a set of ideals do not necessarily mean that the norm or an actor’s commitment to it is weak.18 Also, revolutionary periods can be turbulent and nontransparent, increasing the likelihood of informational asymmetries and misperceptions on the part of those monitoring commitment to the revolution’s ideals. The revolution’s export allows recent converts to rehearse, affirm, and perhaps deepen their commitment to the revolution while simultaneously demonstrating this commitment to the actors distributing the desired moral or material rewards in a transparent and possibly cost-effective way. Alternatively, revolution export might be a strategic campaign by countries whose commitment to the revolution is ambiguous, lacking, or undesirable for political reasons. Whether principled or instrumental, revolution export in these cases is a means of signaling commitment to the revolution.

For example, some suggest that China’s attempt to export revolution to the Third World was partly a means of establishing its own credibility as a revolutionary state.19 Some democracy promotion studies also argue that by appealing to the EU’s self-conception as a “community of liberal-democratic states,” the Eastern European countries have shamed the EU into enlarging, supporting their democratization, and thus demonstrating its commitment to democracy.20 Similarly, some policy studies suggest that eastern EU democracy promotion is related to the EU and NATO integration of these countries, which required them to be democratic. In these accounts, eastern EU democracy promotion has enabled the postcommunist states to demonstrate their new democratic identity to the Euro-Atlantic community and to justify their “place” within that community.21

Therefore, the greater the need of or benefit to a new democracy in demonstrating its democratic identity, the more active its democracy-export efforts.

Domestic Politics: Diffusion Entrepreneurs

In the domestic politics approach, conflict within the revolutionary polity plays out through revolution export.22 Factions of the revolutionary movement might seek to promote its ideals abroad to secure greater power for themselves at home. For example, some argue that during the French liberal and Iranian Islamic revolutions, radicals used revolution export to undermine more moderate forces.23

Moving beyond narrow conceptions of revolutionary export as a manifestation or a byproduct of domestic conflict, support for similar regime change abroad could be understood to be a result of the advocacy of revolutionary movement activists.24 They represent the civic subset of each country’s diffusion entrepreneurs supporting regime change abroad. They mobilize political support for spreading their revolution’s ideals and institutions at home and abroad through reform or more radical means. They can be motivated by strategic concerns (seeking more power on resources for themselves) or by principled considerations (belief that their revolution’s ideals are universal, intrinsically good, or highly desirable form of governance).

This interpretation of the role of domestic politics in fueling revolution export returns agency to the coalitions favoring revolution export and focuses on their preferences/choices and successes/failures to influence policy. It also allows for problematizing the motivation of such actors instead of assuming it. Also, these civic diffusion entrepreneurs might be driven by strategic concerns other than those related to domestic conflict. For instance, some argue that domestic actors sometimes comply with, deploy, and even misuse democratic and human rights norms for various domestic purposes, such as strengthening the domestic commitment to the norm or obtaining domestic and international benefits on account of its adoption.25 This study’s interpretation of the role of domestic politics in driving revolution export further allows for the possibility that domestic actors might be acting for principled reasons. This is an important possibility because some democracy promotion studies suggest that in established democracies, normatively motivated civic movements pressure and persuade their governments to support democracy and human rights abroad.26 In the same way, some argue that the Czech government’s decision to broaden the scope of its Transition Promotion program from assisting the reconstruction of Iraq to democracy promotion around the globe resulted from “strong lobbying” by Czech NGOs.27

Therefore, to the extent that they need to influence their state to place revolution export on its agenda, the stronger the domestic entrepreneurs favoring democracy export, the more active the state’s democracy promotion efforts. These entrepreneurs’ strength can be defined as social movement scholars assess the power of movements to influence policy – as including “worthiness [of the cause], unity, numbers, and commitment [as sustained effort].”28

The International Environment: Soft Balancing and Bandwagoning

The last approach emphasizes the responses of revolutionary states to their external environment. The arguments here are that revolutionary states export their ideals (1) either as a hedge against their enemies or (2) because they are compelled to do so by a powerful ally or want to curry the ally’s favor.

Because revolutionary states feel especially vulnerable to ideological challenges,29 some propose that revolution export is a defense against the powers that threaten the legitimacy and survival of these states. For instance, some find that communist Cuba and China adopted revolution-export policies aimed at weakening and eventually defeating the leader of the imperialist capitalist order, the United States.30 In these cases, exporting revolution is a strategy of ideological balancing and, more generally, “soft balancing” against the revolution’s perceived enemies.31 In other words, in this type of argument, revolution export is a byproduct of international conflict rather than of domestic conflict (as in the domestic politics arguments) or a manifestation of the ideological commitments of the revolutionary state (as in the identity-driven arguments presented earlier).

In this vein, U.S. democracy promotion during the Cold War is sometimes interpreted as a strategy aimed at undermining the USSR.32 The “new battle” against Russia today can likewise be seen as an eastern EU attempt to balance Russia’s expansionism, which has threatened the independence of these countries in the past.33 In the words of a prominent eastern EU diplomat, “shifts to democracy will decrease the influence of Russia in the countries of the former Soviet Union and may thus be considered as security guarantors.”34

Therefore, to the extent that democracy promotion represents a soft balancing strategy, the stronger the perceived threat from nondemocratic powers, the more active a newly democratic state’s democracy promotion efforts.

An alternative international-environment argument is that revolutionary states tend to join the “bandwagon” – that is, they join the efforts of the leading revolutionary state to spread the revolutions’ ideals.35 Such revolutionary states might be trying to curry the favor of the leading revolutionary power or be compelled by it to support the revolution export agenda. The USSR, for instance, obliged its Eastern European satellites to provide aid to “friendly regimes” in the Third World.36 The United States has similarly exerted pressure on its democratic allies to support American efforts to provide development and democracy assistance.37

Likewise, the democracy promotion efforts of the eastern EU countries may be an attempt to align themselves with their main security partner, which is also the most prominent democracy promoter in the world today – the United States. The eastern EU states tend to favor U.S. leadership of world affairs, and the United States has formally and informally conveyed its expectations that the eastern EU states should assist democratization laggards in their region and beyond. A recent example comes from the 2009 speech of U.S. Vice President Joseph Biden in Romania: “You’ve delivered on the promise of your revolution. You are now in a position to help others do the same.”38 As another example, all eastern EU states supported the controversial “freedom agenda,” which included democracy promotion as an objective of the U.S. military intervention in Iraq. Accordingly, the eastern EU democracy promotion policies could be an investment in their alliance with the United States through nonmilitary, ideological cooperation, termed in this chapter “soft bandwagoning.”

Therefore, to the extent that democracy promotion is a policy of soft bandwagoning, the stronger the perceived security (and other benefits) of aligning with a democratic power, the stronger a newly democratic state’s democracy promotion efforts.

It should be noted that identity, domestic politics, and the international-environment factors shaping the foreign policies of revolutionary states are not mutually exclusive. For example, states with a strong domestic commitment to democracy might also harbor a strong contingent of democracy promotion entrepreneurs. Similarly, states with a strong domestic commitment to democracy might also perceive nondemocratic hegemons as more threatening and be more likely to ally with democratic hegemons. Last, powerful coalitions of democracy promotion entrepreneurs might emerge in states with heightened domestic perceptions of the threat posed by nondemocratic hegemons or of the importance of democratic hegemons. Therefore, it is an empirical question whether there are potential interaction effects among these factors.

Explaining Eastern EU Democracy Promotion: The Role of Diffusion Entrepreneurs

How important are the identity, domestic politics, and the international-environment factors in explaining the diversity in the eastern EU democracy promotion practices? The limited availability and quality of relevant data preclude a definitive statistical test of the significance of these factors. Instead, this study uses a paired comparison to evaluate the causal role of each explanatory factor in the context of all factors while also identifying the underlying causal mechanisms. The comparison focuses on Slovakia and Bulgaria39 and draws on original data gathered through in-depth interviews with the key foreign policymakers and civic activists involved in these cases.40 Neither country is atypical of or unusual within the eastern EU group. Moreover, there are many similarities between the two countries with respect to the explanatory factors considered in this study. [See Appendix 2.2 and Appendix Table 2.2.1.] Bulgaria and Slovakia have similar democratization trajectories and comparable commitments to democracy. Both countries also needed to demonstrate these commitments because neither was going to be included in the first wave of eastern EU enlargement. Additionally, Bulgaria and Slovakia have similar friendly pragmatist relationships with Russia. Bulgaria has further demonstrated more support than Slovakia has for U.S. leadership in world affairs. [See Appendix 2.2 and Appendix Table 2.2.1.] So why is it that, despite these similarities, Slovakia is among the most active democracy promoters in the group while Bulgaria has provided little support for democracy abroad?

The Bulgaria-Slovakia comparison suggests that the key difference between the most and the least active eastern EU democracy promoters is the presence of a strong civic advocacy for democracy promotion in the most active democracy promoters, such as Slovakia, and its absence in the least active democracy promoters, such as Bulgaria. Not only does this comparative logic suggest the importance of such civic enterpreneurs, but the analysis of the foreign-policy history of each country, too, points to the same conclusion.41 In both Bulgaria and Slovakia, some of the civic elites who organized the democratic breakthroughs in Bulgaria and Slovakia are also responsible for the introduction and persistence of democracy promotion in these countries. These activists and their NGOs have not only assisted others struggling for democracy but have also sought to embed democracy promotion in their country’s foreign policy. Only in the Slovak case, however, where such democracy entrepreneurs represented a large and united group that articulated resonant arguments in favor of supporting democracy abroad, was democracy promotion incorporated into the foreign policy of this new postcommunist democracy.

The Slovak case is particularly instructive because Slovakia is one of the eastern EU countries least likely to be an active democracy promoter. Slovakia was initially a democratization laggard. As a small and young state, economically dependent on the EU and energy dependent on Russia, it is not necessarily expected to have the ambitious and proactive foreign policy that democracy promotion requires. In addition, there are other eastern EU countries that are stronger democracies, more pro-American and/or more anti-Russian, which have nonetheless provided (much) less support for democracy abroad. So explanations that emphasize the identity or international environment of eastern EU democracy promotion (i.e., leaving out the civic advocacy factor) would be unable to account for the fact that Slovakia has promoted democracy fairly consistently over the last decade, regardless of the party in power.

Normative Commitment to Democracy

The 1997 Bulgarian democratic breakthrough and the 1998 Slovak one were part of the same sub-wave of democratization in Central and Southeastern Europe.42 This wave swept through states with transitions arrested by illiberal rulers, who were defeated when their civic and political oppositions mobilized the citizenry in defense of democracy.43 In both Bulgaria and Slovakia, these breakthroughs were prepared in part by elites and demanded by publics committed to democracy.44

Although Bratislava began supporting Serbia’s democratization only a year after its breakthrough, Sofia took no such actions. Yet, there is little support for the argument that Sofia’s lack of initiative stems from a lack of democratic commitment. In fact, democracy was accepted as “the only game in town” fairly early on in Bulgaria’s transition.45 Indicative is the fact that most key Bulgarian foreign policymakers in the transition period had a personal commitment to democracy that could have defined their foreign policy. Consider, for instance, the profile of the first postbreakthrough foreign minister of Bulgaria, Nadezhda Mihajlova, who began her political career in opposition to the Bulgarian communist regime and later became one of the 1997 breakthrough leaders. After leaving office, Mihajlova became the board chair of the Institute for Democracy and Stability in South-Eastern Europe. Similarly, her successor, Solomon Passy, is also a renowned anticommunist dissident and human rights activist. Even when the successors of the former illiberal rulers returned to power, they also appointed a foreign minister with experience in various European international organizations and a commitment to European values (including democracy) – Ivailo Kalfin. Some of these successor elites have never fully internalized some democratic norms & practices but in Slovakia, there are also such elites – successors of the former illiberal unless who similarly have a questionable committment to democracy. Consider that Bulgaria’s Freedom House average combined score for civil liberties and political rights (1.5 out of 7 and 2.93 out of 7 as overall democracy score) during these successors’ term is further comparable to Slovakia’s (1.0 and 2.39 overall democracy score) during the reign of the Slovak successors of the former illiberal rulers. Still, although all these Bulgarian foreign policymakers occasionally expressed solidarity with other peoples fighting for democracy,46 Sofia made few sustained efforts and developed no strategy to promote democracy.

Slovakia, although among the most active eastern EU democracy promoters, is not among the best eastern EU democracies. Similarly, the country with the highest Freedom House overall democracy score in the eastern EU group, Slovenia, is among the least active democracy promoters in the group. These cases thus present strong evidence against the proposition that countries that are democratization leaders are also the ones that choose to spread their ideals abroad.

Democracy Promotion Entrepreneurs

In contrast to the internalization of democracy in Bulgaria and Slovakia, the advocacy of the civic organizers of the democratic breakthroughs in Bulgaria and Slovakia were much more consequential. A number of these activists with strong and salient transnational ties began almost immediately sharing best practices from their own democratic breakthroughs with other postcommunist elites. (Chapter 3 will discuss in detail the motivations of the eastern EU civic democracy promoters.) The potential of the Bulgarian and the Slovak revolutions to serve as models for defeating illiberal incumbents reigning in electoral democracies was immediately recognized by their organizers, by other prodemocracy activists in the region, and by some U.S. donors.47 With U.S. funding and support, key Bulgarian civic breakthrough organizers coached prodemocracy actors in Slovakia in 1997, Macedonia in 1998, and Serbia in 1999.48 Similarly, with U.S. funding and support, in 1999 several Slovak NGOs began assisting prodemocracy activists in Serbia, Croatia, Ukraine, and Belarus.49

Soon thereafter, these Slovak activists also began lobbying the new Slovak government (staffed with many former prodemocratic opposition allies) to support democracy abroad. When asked how Bratislava began promoting democracy in Serbia, the key foreign policymakers of the late 1990s recalled that the Slovak NGOs already working in Serbia approached them to put the question of Slovak democracy promotion in Serbia on the table.50 These activists succeeded in convincing Bratislava to support the democratization of this important western Balkans country.51 The Slovak foreign policymakers chose to pay attention to the Slovak democracy promotion entrepreneurs because they presented a united and authoritative movement behind a (morally acceptable) and convincing solution to Slovakia’s main foreign-policy challenges that had not been effectively addressed. These activists not only represented several of Slovakia’s most prominent NGOs and breakthrough organizers, such as the Pontis Foundation, Civic Eye, and Memo 1998, they also coordinated their advocacy in favor of Slovak democracy promotion in Serbia. Also, as Chapter 4 discusses in detail, the activists appealed not only to the democratic commitments and solidarity of Slovak diplomats but mostly to their understanding of the benefits of a democratic neighborhood for Slovakia, namely security and prosperity. These arguments resonated because they were based on a shared understanding of the benefits that resulted from Slovakia’s own democratization: just as democracy had been the antidote for Slovakia’s illiberal nationalism and international isolation, so could democracy be the remedy for the weak, isolated, and nationalistic autocracies in Slovakia’s neighborhood. Moreover, Bratislava also saw its democratization-support efforts in Serbia as beneficial to Slovakia’s efforts to secure its membership in the EU and NATO, which also viewed the instability in the western Balkans as a security threat.

Slovak diplomats and NGOs successfully mobilized a number of prominent international actors to join their initiative in support of democracy in Serbia.52 The so-called Bratislava Process helped prepare the Serbian opposition to organize an electoral revolution in 2000 (See Box 4.2 in Chapter 4).53 When the Process activities ended, Slovakia set up a special Bratislava-Belgrade Fund to support development projects, including democracy building, in Serbia.

By that time, Slovakia had negotiated its EU and NATO membership and was debating its postaccession foreign policy. The Slovak civic democracy promoters insisted that Bratislava continue to promote democracy as a way of both stabilizing its southeastern neighbors and participating in the EU’s external relations; they also urged Bratislava to begin promoting democracy to the east (especially Ukraine and Belarus) for similar reasons.54 Furthermore, by realizing democracy-assistance projects through the Slovak development aid system, which was established in 2004, these Slovak NGOs helped transform this aid system into (and benefited from its becoming) a platform for democracy promotion. Also, a number of NGO activists had joined the government, consequently representing additional allies to the democracy promotion advocates. The movement, a contingent of Slovak NGOs regularly working on democracy-related projects abroad and lobbying the Slovak state in favor of democracy promotion, had grown to more than a dozen groups. They included some of the most influential NGOs in the country, several of which were also internationally recognized for their democracy work at home and abroad.55 In their advocacy, they were a large and united group.56 In sum, these Slovak democracy promotion champions represented a strong movement able to articulate resonant arguments. Swayed by both this advocacy and the success of the Bratislava Process, Slovakia institutionalized democracy promotion and made it a foreign-policy priority.57

In contrast, Bulgaria’s democracy promotion entrepreneurs were weaker and therefore less successful. A democracy promotion movement never emerged in Bulgaria. As in Slovakia, the former prodemocratic opposition allies of the Bulgarian activists were in power, so the NGOs involved in the western Balkans in the late 1990s kept the Bulgarian cabinet “apprised” of their initiatives.58 They never presented a united front, however, and made only weak attempts to convince Sofia that backing their efforts would be good foreign policy. Some never even explicitly argued that the Bulgarian state should support democracy in the western Balkans.59 Like Slovakia, Bulgaria had suffered spillover from the region’s ethnic conflicts and viewed Serbian nationalism as a regional problem.60 At the same time, Bulgaria, again like Slovakia, was overwhelmed by the challenges of moving forward with its Euro-Atlantic integration. The Slovak activists addressed the potential costs of democracy promotion (possible tensions with Serbia and diverting resources that could have gone to the country’s Euro-Atlantic integration) by convincingly reframing them as benefits (resolving Serbia’s nationalism and improving Slovakia’s EU and NATO membership chances); the Bulgarian activists, however, failed to persuade their political allies that democracy promotion could solve these foreign-policy problems. As a result, Sofia offered only rhetorical rather than substantive support for the democratization of the western Balkans.

In the early 2000s, the number and geographic reach of the Bulgarian democracy promotion NGOs increased somewhat.61 There were more than a half-dozen organizations with democracy promotion programs (rather than ad hoc projects). Although fewer in number than those in smaller Slovakia, these Bulgarian NGOs were prominent organizations. Yet their advocacy continued to be weak and disorganized.62 The NGOs approached the relevant (and like-minded) foreign policymakers, including Minister Passy, only sporadically and only one or a few at a time. According to these policymakers, they interpreted this advocacy as requests for supporting these NGO’s own work abroad rather than as conversations about Bulgaria’s foreign policy.63

Would the Slovak prodemocracy politicians, who assumed power in the late 1990s and early 2000s, have supported democracy abroad in the absence of the advocacy of the Slovak civic democracy entrepreneurs? Most likely, they would have provided some rhetorical support and demonstrated some solidarity, episodically and on an ad hoc basis, as their Bulgarian colleagues also did on occasion. The Bulgaria-Slovakia comparison suggests that the discussions between the key foreign policymakers and the democracy promotion movements were crucial in creating and publicizing a resonant narrative about the need for and benefits of democracy promotion. This narrative is based on the arguments that the civic democracy entrepreneurs made in favor of their state supporting democratization abroad. This narrative informs to this day the Slovak democracy promotion rationales, justifying the institutionalization of democracy promotion and ensuring its survival after turnover in power. It was thus the Slovak civic advocacy that allowed democracy promotion to become a systematically and actively implemented diplomatic tradition rather than simply the personal mission of a few politicians with commitment to democracy. As a result, Slovakia has promoted democracy fairly consistently since 1998, regardless of the party in power.

A brief side comparison with the Czech Republic is instructive here. [For a short history of the Czech Republic’s efforts to support democratization abroad, see Appendix 2.3.] As the leader of the Czech anticommunist opposition forces, Vaclav Havel became the president of Czechoslovakia in 1989 and continued to serve, after its dissolution, as president of the Czech Republic until 2003. Under the leadership of Havel and his former opposition colleagues, who assumed different foreign-policy posts, the Czech Republic issued a number of statements condemning violations of human rights and democracy around the globe and supported multilateral sanctions against offending regimes. Prague also volunteered to serve on the steering committee of the Community of Democracies and supported the democratization of the western Balkans through its contribution to various regional multilateral initiatives, such as the Stability Pact for South-East Europe.

It was mostly in the early 2000s, however, when the Czech civic democracy promoters weighed in on their country’s post–EU–accession foreign policy, that Prague moved from such expressions of solidarity to more systematic support of democracy abroad through a variety of policy instruments. Thanks to the advocacy of the Czech democracy promotion movement, the Czech government institutionalized democracy promotion as a foreign-policy priority and created a Transition Promotion unit in the foreign ministry; the Czech state further moved beyond criticism of offending states and following the lead of multilateral organizations.64 Since then, consecutive Czech governments have expanded the level and reach of Prague’s aid and of Prague’s bilateral and multilateral diplomatic support for democratization abroad. In sum, as in the Slovak case, democracy promotion transitioned from a personal mission of a few politicians with commitment to democracy to a systematically and actively implemented foreign-policy priority as a result of the advocacy of the country’s democracy promotion movement.

The advocacy of the Slovak movement was crucial not only in embedding democracy promotion in Slovakia’s foreign policy but also in keeping it high priority on the agenda. When the descendants of the prebreakthrough illiberal rulers returned to power in 2006, the Slovak civic democracy promoters launched a strong public campaign in favor of continued official democracy promotion. According to local policy observers, the strength of this campaign, as indicated by the reputation and number of these activists and the organizational strength of the participating NGOs and their ability to mobilize the citizenry, ensured that they “continued to wield the authority to influence [Slovak] public opinion and the actions of the [Slovak] political elite” in favor of democracy promotion.65 The ruling coalition signed an agreement confirming its commitment to democracy at home and abroad. In addition, the ruling coalition appointed two foreign ministers who were internationally recognized for their democracy promotion work and who accordingly continued the democracy promotion policies of previous governments. Although to a lesser degree, the government also continued to cooperate with, build on the work of, and delegate responsibilities to the Slovak NGOs providing democracy assistance to priority recipients in the east and southwest.66 A weaker democracy promotion movement might have been unable to pressure this government into supporting democracy abroad, thus leaving Slovakia in the group of moderate or weak democracy promoters. The history of Slovakia’s democracy promotion in the mid-to-late 2000s thus provides additional evidence of the importance of civic advocacy in ensuring continued and strong official democracy promotion.

If the Slovak movement used the period before and after Slovakia’s EU accession to consolidate the democracy promotion agenda introduced after Slovakia’s democratic breakthrough, their Bulgarian counterparts were unsuccessful in influencing Bulgaria’s post–EU–accession foreign-policy debate.67 Their activism gradually dwindled with declining demand for their expertise by fellow activists abroad, the withdrawal of U.S. donors from Bulgaria, and increased EU criticism of Bulgaria’s democratization.68 The few civic democracy promoters joined other international development NGOs and, after a few years of disagreements and inaction, finally formed a platform poised to pressure the Bulgarian state to begin providing development aid as required by the EU.69 Such a system is slowly being put in place, but because the share of the democracy promoting NGOs in the platform is so small, they have failed to have democracy promotion defined as a development aid priority.70

Signaling

In the late 1990s, both Bulgaria’s and Slovakia’s efforts to “fast track” to EU and NATO accession derailed because of problems with democracy at home.71 Both the Slovak and the Bulgarian democracy promotion entrepreneurs sought to take advantage of this uncertainty about their countries’ EU and NATO accession. The highly desired Euro-Atlantic membership, however, did not by itself entice the Bulgarian or Slovak foreign policymakers to promote democracy as a strategy of signaling their commitment to the norm. Rather, it was the advocacy of the Slovak democracy promotion movement that made those concerns part of Slovakia’s democracy promotion rationale: as discussed previously, these activists convinced Bratislava that democracy promotion is, among other things, a means to earning Slovakia’s EU and NATO membership. The frame the Slovak entrepreneurs used in their advocacy was in part about EU and NATO membership. In some of the other eastern EU countries, however, other frames were used, as Chapter 4 demonstrates. Also, the same frame about EU and NATO membership was inconsequential in Bulgaria because of the general weakness of the Bulgarian democracy promotion entrepreneurs. Given that weakness, even their calls for Sofia to abide by the EU’s guidelines for providing development aid, including democracy assistance, remained unanswered. It is thus also difficult to argue that the domestic politics and signaling factors need to be combined to explain eastern EU democracy promotion.

In addition to Bulgaria and Slovakia, Romania was the other country, which in the late 1990s needed to prove, consolidate, and project its new democratic identity in order to join Euro-Atlantic community. Slovakia was the only one of the three countries to catch up with the first-wave EU applicants, thus having its democratic credentials recognized; yet Slovakia continued to be one of the most active eastern EU democracy promoters. Romania and Bulgaria were left behind to advance in their own second wave of eastern EU enlargement; thus, they both had a fairly equal need to demonstrate their commitment to democracy. Yet they have not been both equally interested in supporting democracy abroad. Bulgaria has invested little in supporting democracy abroad, whereas Romania has taken some diplomatic initiative (even if it has been rather less active than Slovakia). In the context of the Slovakia-Bulgaria comparison, the Romanian case mounts further evidence against explanations of eastern EU democracy promotion as a signaling strategy.

Soft Balancing

Likewise, there is no support for the argument that a perceived Russian threat explains the difference in democracy promotion efforts between Bulgaria and Slovakia. First, Bulgaria and Slovakia are similarly dependent on Russian oil and have had similarly accommodating policies toward and threat perceptions of Russia. Yet only in Bulgaria do civic and political elites express concern that their state is hesitant to support democracy abroad to avoid “stepping on Moscow’s toes.”72

Second, in other eastern EU countries, concerns about Russia’s influence in the region have been used to justify, not to discourage, democracy promotion. As Chapter 4 demonstrates, many Poles have felt that their country’s independence is threatened by Russia and that Polish expansionism was an ineffective but the only articulated solution to this threat until a strong, authoritative group of Polish dissidents argued resonantly that “freedom promotion” in the mutual Polish-Russian neighborhood would weaken Russian imperialism and would thus be a better solution. In other words, in the Polish case, as in the Slovak one, the explanatory leverage rests not with the perceived balance of threat but once again with the strength of the democracy promotion entrepreneurs. Moreover, there are no interaction effects between the domestic-politics and balance-of-power factors. The frame the Polish entrepreneurs used in their advocacy was about addressing the country’s geopolitical vulnerability, which happened to be the Russian threat; in some of the other eastern EU countries, however, other frames were used, as the Slovak case demonstrates.

Third, consider also that the most active eastern EU democracy promoters represent the full spectrum of attitudes toward Russia – from Slovakia, which sees little threat in Russia and seeks to maintain a relatively close relationship with it, to the Czech Republic, which is only somewhat distrustful of Russia, to Poland, which remains “deeply fearful of Russia.”73

In sum, taken together these Bulgaria-Slovakia, the Poland-Slovakia and the Poland-Slovakia-Czech Republic comparisons make it difficult to argue that there are interaction effects among the domestic-politics and international-environment explanatory factors considered in this study.

Soft Bandwagoning

Last, alignment with and pressure by the United States was similarly not very influential on Bulgaria’s and Slovakia’s democracy promotion efforts. Bulgaria has aligned with the United States on many important occasions and is one of the more pro-American countries in the eastern EU group: in the early and mid-2000s, Sofia even actively lobbied to host a U.S. military base.74 At about the same time, U.S. diplomats began conveying to Sofia their belief in the value of the Bulgarian democratization model.75 Washington also offered Bulgaria support for initiatives meant to facilitate the sharing of this experience with neighboring countries and proposed to make Bulgaria a regional hub for a number of U.S. democracy promotion programs.76 Bulgaria, however, did not take advantage of this opportunity and remained largely uninterested in promoting democracy.

The Hungarian case is also instructive here. With U.S. encouragement and pressure to be an active democracy promoter,77 Budapest set up an International Centre for Democratic Transition as the Hungarian contribution to the Community of Democracies.78 But Budapest is currently financing only the operation of the institute, which relies on external donors for individual project funding.79 More generally, Hungary remains a hesitant and reluctant democracy promoter: Hungary’s democracy aid is perhaps the most fragmented assistance program among the eastern EU donors; Budapest’s activism on issues beyond minority rights is rather low; and even minority rights have been pursued not in the framework of democracy promotion but within the framework of cross-border cooperation. In other words, in addition to the Bulgarian case, the Hungarian case mounts further evidence against explanations of eastern EU democracy promotion as a soft-bandwagoning strategy.

In sum, that Slovakia is among the most active eastern EU democracy promoters and Bulgaria is the least active one is a result that can be attributed to the one theoretically important dimension on which these countries differ, namely, the presence of a strong democracy promotion movement in Slovakia and its absence in Bulgaria. The Slovak movement’s advocacy was crucial for embedding democracy promotion in the country’s foreign policy, for elevating its importance, and for keeping it high on the agenda through turnovers in power. These civic activists not only monitored and pressured their state but also advised and assisted it in implementing democracy assistance abroad. In contrast, the weakness of the Bulgarian democracy promotion advocates, a small and fragmented group of NGOs unable to articulate or present resonant arguments, prevented these entrepreneurs from effectively pressuring or persuading Sofia to promote democracy.

Appendix 2.2 includes a simple statistical test that further examines the importance of the identity, domestic politics, and the international-environment factors in explaining the diversity in the eastern EU democracy promotion practices. The test confirms the strong relationship between the advocacy of the eastern EU democracy promotion entrepreneurs and the democracy promotion activism of their states. The test also confirms that there is no meaningful relationship between eastern EU democracy promotion and any of the other explanatory factors. Because the test takes into account all eastern EU cases, it also bears out the generalizability of the findings of the paired comparison – in brief, these findings are not specific to Bulgaria and Slovakia alone but apply to the eastern EU group as a whole.

Even if the eastern EU international environments and identities do not drive the democracy promotion activism of the eastern EU states, these two factors have not been inconsequential: they may not have influenced whether an eastern EU state provides more or less support for democracy abroad but they have nonetheless shaped the rationales behind such support. As Chapter 4 discusses, Polish democracy promotion has been in part about counterbalancing Russian power, Czech democracy promotion has a strong normative rationale behind it and Slovak democracy promotion has an important signalling dimension. When advocating in favour of their states supporting democratization abroad, the eastern EU civic democracy promotion entrepreneurs put forward arguments that addressed the moral and/or the strategic concerns confronting the eastern EU foreign policymakers. As the Slovak case illustrates, these advocacy frames and the resultant state-society foreign policy conversations created narratives about the need for and thus the rationales behind democracy promotion. These rationales, in turn, regulate under what circumstances democracy promotion was prioritized above and sacrificed for other foreign policy goals and which recipients each eastern EU democracy promoter prioritized. Note, however, that the activists in different eastern EU countries used different frames and that it was the strength of these activists that decided the impact of the frames evoking the eastern EU international environments and/or identities (as demonstrated by the Bulgaria-Slovakia comparison presented earlier). It is thus difficult to argue that the domestic politics and the other two factors need to be combined to explain eastern EU democracy promotion.

So why is it that some countries have stronger democracy promotion entrepreneurs than others? As the case studies suggested, strong democracy promotion entrepreneurs neither emerged nor succeeded as a result of their countries’ commitment to democracy, the perceived threat posed by nondemocratic hegemons, or the perceived importance of democratic hegemons.80 Instead, some of the Bulgarian policymakers and civic activists interviewed for this chapter noted the general fragmentation of the Bulgarian civil society both on domestic and on foreign-policy issues.81 In contrast, Slovak NGOs have a strong record of working together and with their governments on both domestic and foreign-policy issues through different formal and informal mechanisms.82 Also, as the Bulgarian and Slovak case studies suggested and Chapter 3 will discuss in detail, the number of these entrepreneurs is related to their inclusion in relevant and salient translational solidarity networks. This finding parallels previous work on forcible regime promotion and waves of regime change, which also emphasizes the important role of transnational networks in setting regime promotion in motion.83 Last, as Chapter 4 will discuss, what made the arguments of the Slovak democracy promotion entrepreneurs resonant was that they bridged two sets of shared understandings among civic and political elites in Slovakia: (1) the political and economic benefits that resulted from Slovakia’s democratization (and that could similarly be expected to accrue in other countries in the region as a result of their democratization) and (2) the foreign policy challenges Slovakia faced that could potentially be addressed through democracy promotion (namely by bringing about in other countries political and/or economic improvements similar to the ones brought about by Slovakia’s democratization). In contrast to the Slovak activists who thus credibly reframed the costs of democracy promotion as benefits, the Bulgarian entrepreneurs failed to articulate arguments that presented democracy promotion as a sound solution to Sofia’s important foreign-policy concerns.

Eastern EU Democracy Promotion in Context

As discussed in Chapter 1, in addition to the eastern EU countries, there are other third-wave democracies that have similarly supported the democratization of their neighborhoods. Did domestic politics similarly influence those other countries’ emergence as democracy promoters? It is beyond the scope of this book to answer this question in a systematic and comparative fashion. There is some evidence, however, suggesting that the relationship between the strength of the democracy promotion entrepreneurs and the level of state support for democracy abroad discussed in this chapter with respect to the eastern EU countries also holds for new democracies in other regions. Some have argued that Indonesia’s democracy promotion activism ones to the strong advocacy of the country’s civic democracy promoters.84 In the early 2000s, a few influential academic activists began arguing and were increasingly backed by a number of other civic activists and groups, insisting that their government conduct a foreign policy that reflects Indonesia’s new democratic identity.85 Similarly, others have found that the South African civil society, and especially its trade unions, have played an important role in convincing their government to support democratization rather than friendly autocrats abroad.86

When considering the generalizability of this chapter’s findings, however, two types of caveats are in order: (1) caveats about the eastern EU cases compared to other third-wave democracies; and (2) caveats about the third wave of democratization compared to other revolutionary waves.

Eastern Europe Compared to Other Third-Wave Democracies

When compared to other third-wave democracies, Eastern Europe is one of the regions with the strongest regional identity. Not only are there significant similarities among the political (and economic) regimes in the region – a product of their shared communist past and their similar transitions away from communism – but even more important, there is also “an assumption of [such] fundamental similarities” as well as dense bilateral and multilateral ties that bind these countries together.87 These linkages and perceived similarities create an especially favorable environment for regional diffusion.88 Although there are other regions with developed regional identities such as Latin America, the Middle East, and, to a lesser extent, Africa, other regions, such as Asia, are more politically diverse and divided. Even in Eastern Europe, however, some fairly strong regional subidentities have developed over time: East Central Europe, Southeastern Europe, Eastern Europe, South Caucuses, and Central Asia. The ways in which differences in the strength of regional identity over time and across regions impact diffusion beg further examination.

The eastern EU states used to provide assistance to developing countries before the collapse of communism.89 Even though they did not do so voluntarily but rather were obliged to support friendly regimes in the Third World by the USSR, this practice created an appreciation for the usefulness of aid as a foreign-policy tool and a tradition of exporting successful political, economic, and social “best practices” abroad.

Relatedly, Eastern Europe also includes mostly developed countries. Despite the economic collapse in all these countries in the early transition years and the challenges presented by the simultaneous transition to market and to democracy, even by the mid-1990s, four of these ten countries were already OECD members and two more became members in the 2000s. Such high levels of development make these countries capable of providing greater amounts of assistance, more systematic aid, and additional support beyond technical democracy assistance. These high levels of development have also underscored the success of the eastern EU democratic transitions and reinforced the perception that these transitions represent valuable models that could and should be exported. Perhaps this positive relationship between the economic and the political restructuring of the eastern EU countries accounts for the prevalence of strategic rather than normative rationales for democracy promotion (as Chapter 4 discusses). The eastern EU countries are, of course, far from unique in their level of development – South Korea, Chile, Argentina, Botswana, and Malaysia are good examples of other developed new democracies. Still, the relationship between democracy promotion and its rationale on the one hand and democratization and development on the other hand deserves further attention.

With a few other exceptions, such as South Korea, for example, the eastern EU countries are perhaps most unique within the group of third-wave new democracies in terms of their relationship to the West. Unlike many other new democracies witnessing the West’s efforts to project its democratic values abroad, the eastern EU countries are not burdened by the association of the West as a group of former imperial powers imposing their governance systems on their colonies. In fact, for much of Eastern Europe, the end of the Cold War was a “victory” for the democratic West over the regional imperial power, the USSR, and its governance system. Aspiring to the practices, values, and ideals of the West and joining the Euro-Atlantic community was a national priority for all the eastern EU countries after their democratic breakthroughs.90 Furthermore, the democratic conditionality of both the NATO and the EU enlargement processes served as powerful affirmations of the completion of the eastern EU transitions and the democratic identity of these countries. Consequently, joining these organizations has served to underscore the success of the eastern EU transitions in the eyes of their elites, thereby also reinforcing the understanding that these transitions represent valuable models that could and should be exported.

The Third Wave of Democratization Compared to Other Revolutionary Waves

As discussed in Chapter 1, when compared to other revolutionary states, the eastern EU countries and the other third-wave democracies are perhaps most unique in that (1) they embraced what soon became an “ideology for humankind”91 and (2) almost simultaneously, the promotion of that ideology abroad began to encounter skepticism and fatigue.92 It is perhaps this first political reality that accounts for the fact that democracy promotion has been accepted as a foreign-policy goal even by the elite successors of those replaced by the third wave of democratizations. Whether the second political reality makes new democracies today less concerned about or more willing to support democracy abroad relative to previous revolutions is perhaps best tested empirically.

Finally, some students of revolution have already documented that there are important differences across revolutionary waves in the organizational bases of revolutionary movements, which have in turn impacted different aspects of regime change diffusion. For example, some suggest that regime change diffused more quickly but less successfully in the 1848 versus the 1917 to 1919 liberal revolutionary wave because the effective locus of contentious decision making shifted from crowds to the leaders of broad-based party and union organizations.93 Accordingly, even if the eastern EU diffusion entrepreneurs have been mostly civic elites, revolution-export advocates in other regions and other waves might have different backgrounds and coalitions. The eastern EU countries are mostly small countries with relatively simple foreign-policy processes and very few veto players.94 In larger and more complicated polities, however, regime change diffusion entrepreneurs might have to prepare more broad and ambitious campaigns and still succeed more rarely.

Conclusion

In brief, with some important caveats, this chapter documents that the eastern EU civic diffusion entrepreneurs played an important role in embedding regime export in their states’ foreign policies. The export of one’s ideals, innovations, and experiences is a common thread in the literatures on revolution, diffusion, and democracy assistance but has been previously overlooked, in part because these literatures have ignored each other and in part because of the tension between structure and agency. If the literature on diffusion has been overly structural and the literature on democracy promotion has focused most on the agents behind democracy promotion, works on revolutionary states have focused on the identity, domestic politics, or international environments of these countries. This chapter added to the literature on the influence of domestic politics on revolution export but moved beyond previous narrow and structural conceptions of the role of domestic politics in the foreign policy of revolutionary states. Instead of focusing on domestic conflict, this study emphasized the important agency of diffusion entrepreneurs-activists and their belief in the potential of their revolution to positively reshape both the domestic and the international order of their countries. If a number of revolutions have produced such entrepreneurs, only in some countries have these entrepreneurs managed to embed their agenda in their states’ foreign policies. Like some previous work on social movements and on norms,95 this chapter suggests that the strength of their advocacy is rooted in their ability to unite in numbers and articulate an authoritative and resonant narrative that reframes the costs of revolution export as benefits. It is the efforts and motivations of these entrepreneurs-activists that become the focus of the next chapter. If this chapter has provided an explanation of the poorly understood transformation of certain countries from adopters of diffusion practices into their exporters, Chapter 3 will explain how certain NGOs have undergone this adopter-to-exporter transformation.

1 Wlodzimierz Cimoszewicz, Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Poland, describing his country’s commitment to democracy (“Information of the Government of the Republic of Poland,” Warsaw, Poland, 2003).

2 See, for example, Schraeder Reference Schraeder2002.

3 To the extent that new democracies have supported democracy abroad, they have commonly done so without much of a strategic vision or planning. Their efforts are also most frequently limited to concern about the record of a handful of their neighbors. In addition, maintaining good relations with their neighbors has frequently constrained the engagement of new democracies on human rights and democracy abroad. Perhaps most important, they are often hesitant to publicly confront antidemocratic practices or openly embrace a democracy agenda. See, for example, Carothers and Youngs Reference Carothers and Youngs2011; Stuenkel and Jabin Reference Stuenkel and Jabin2010.

4 Starr Reference Starr1991; Gleditsch, Skrede, and Ward Reference Gleditsch and Ward2006; Brinks and Coppedge Reference Brinks and Coppedge2006; Fournier 1998.

5 Herman and Piccone Reference Herman and Piccone2002.

7 Walt Reference Walt1992. There are two types of revolutions: central revolutions, which articulate a novel vision for changing their domestic and possibly the international order, and affiliate revolutions, which voluntarily embrace the ideology of and align themselves with the central revolution (Katz Reference Katz1997). The cases described in this book are of affiliate revolutions.

8 Halliday Reference Halliday1999, 100; Walt Reference Walt1992.

9 Katz Reference Katz1997.

10 Halliday Reference Halliday1999, 103–4.

11 Armstrong Reference Armstrong1993, 174.

12 Risse-Kappen Reference Risse-Kappen1995; Smith Reference Smith1994.

13 Jonavicius Reference Jonavicius2008.

14 Vaclav Havel et al., “Europe Needs Solidarity Over Cuba,” Guardian, March 18, 2008.

15 , Foreign Policy of the Czech Republic (Prague, Czech Republic: Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2005), 7.

16 The commitment to externalizing the revolution’s ideals could be reinforced through socialization by previous similar revolutions. The PolishAid promotional materials, for instance, list “We ourselves received assistance” as one reason why “We provide [development, including democracy,] assistance” (http://www.polishaid.gov.pl/Why,We,Provide,Assistance,204.html).

17 Hyde Reference Hyde2011; Alcaniz 2012.

18 Finnemore and Sikkink Reference Finnemore and Kathryn1998.

19 Armstrong Reference Armstrong1993, 178.

20 Schimmelfennig Reference Schimmelfennig2001.

21 Kucharczyk and Lovitt Reference Kucharczyk and Lovitt2008; Jonavicius Reference Jonavicius2008.

22 See also Owen Reference Owen2010.

23 Blanning Reference Blanning1986; Arjomand Reference Arjomand1988.

24 In theory, domestic pressure for democracy promotion abroad could include popular demand. In practice, however, most citizens tend to be more interested in domestic than in foreign-policy issues. Also, eastern EU foreign policy makers report that they are uncertain about their citizens’ preferences on democracy promotion. Interview with E. K., Slovak foreign policymaker, November 28, 2008; and interview with M. M., Polish foreign policymaker, October 13, 2008.

25 Moravcsik Reference Moravcsik2000; Subotic Reference Subotic2009; Hyde Reference Hyde2011.

26 On democracy export, see Brookings Institution 2011. On human rights promotion, see Sikkink Reference Sikkink2004 and Simmons Reference Simmons2009.

27 Kucharczyk and Lovitt Reference Kucharczyk and Lovitt2008.

28 Tilly 2004, 53.

29 Walt Reference Walt1996.

30 Armstrong Reference Armstrong1993.

31 Soft balancing is a strategy of balancing the dominant state in the regional or international system through the use of nonmilitary actions (Pape Reference Pape2005; Paul Reference Paul2005). On balancing against perceived threats, see Walt Reference Walt1990.

32 Carother Reference Carothers1999.

33 Jonavicius Reference Jonavicius2008.

34 Quote by Vahur Made, cited in Jonavicius Reference Jonavicius2008.

35 On bandwagoning, see Schweller Reference Schweller1994; Powell Reference Powell1999. See also Owen Reference Owen2010.

36 Wettig Reference Wettig2008.

37 Schraeder Reference Schraeder2002.

38 Baker Reference Baker2009.

39 Bulgaria and Slovakia represent a most-similar-cases comparison. On most-similar cases as optimal for theory testing and theory building, see Gerring Reference Gerring2007, 89.

40 All 112 interviews were conducted in confidentiality; interviewee names and positions are withheld by mutual agreement. The interviewees included all key relevant activists and foreign-policy elites (within the foreign ministries, prime ministers’ and presidents’ offices, and development-aid system) as well as other knowledgeable observers, such as foreign donors, journalists, and policy analysts.

41 The Bulgaria-Slovakia comparison thus combines the qualitative comparison method with process tracing. On process tracing, see George and McKeown 1985 and George and Bennett Reference George and Bennett2005.

42 Vachudova Reference Vachudova2005.

43 Bunce and Wolchik Reference Bunce and Wolchik2011.

44 Their export commitment was reinforced through socialization by Western democracy promoters, but the importance of this socialization should not be overstated. For example, some have reported that there are significant differences in the perceived indebtedness to external actors among the most active eastern EU democracy promoters – Poland, the Czech Republic, and Slovakia (Butorova and Gyarfasova Reference Butorova and Gyarfasova2009). Also, two of the top recipients of USAID Democracy and Governance Aid – Bulgaria and Romania – for example, are among the least active eastern EU democracy promoters.

45 Dimitrov Reference Dimitrov2002 and Giatzidis Reference Giatzidis2002.

46 Interview with S. P., Bulgarian foreign policymaker, September 1, 2011; and interview with S. V., Bulgarian activist, July 25, 2011.

47 Interview with P. D., Slovak activist, November 20, 2008; interview with J. K., Slovak activist, November 27, 2008; interview with I. K., Slovak foreign policy analyst, November 21, 2008; interview with D. K., Bulgarian activist, July 11, 2011; interview with L. L., U.S. donor representative, June 18, 2010; and interview with R. H., U.S. donor representative, August 18, 2010.

48 Interview with D. K., Bulgarian activist, August 10, 2011; and interview with R. S., Bulgarian activist, October 22, 2009.

49 Interview with M. M., Slovak activist, July 27, 2007; interview with P. N., Slovak activist, November 11, 2008; and interview with P. D., Slovak activist, November 26, 2008.

50 Interview with E. K., Slovak foreign policymaker, November 28, 2008; and interview with K. V., Slovak foreign policymaker, November 19, 2008.

51 Interview with E. K., Slovak foreign policymaker, November 28, 2008; and interview with M. M., Slovak activist, July 27, 2007.

52 Forbrig and Demes Reference Forbrig and Demes2007.

53 Bunce and Wolchik Reference Bunce and Wolchik2011.

54 Interview with A. D., Slovak foreign policy analyst, July 27, 2007; interview with P. D., Slovak activist, November 26, 2008; and interview with E. K., Slovak foreign policymaker, November 28, 2008.

55 Interview with L. L., U.S. donor representative, June 18, 2010; and interview with R. P., U.S. donor representative, October 19, 2008.

56 Interview with E. K., Slovak foreign policymaker, November 28, 2008; and interview with J. M., Slovak foreign policy analyst, November 27, 2008.

57 Interview with J. M., Slovak foreign policy analyst, November 27, 2008; and interview with I. K., Slovak foreign policy analyst, November 21, 2008.

58 Interview with R. S., Bulgarian activist, October 22, 2009; and interview with D. K., Bulgarian activist, August 10, 2011.

59 Interview with S. V., Bulgarian activist, July 25, 2011; interview with D. K., Bulgarian activist, August 10, 2011; and interview with S. P., Bulgarian foreign policymaker, September 1, 2011.

60 It should be noted that Bulgaria and Serbia are direct neighbors, while Slovakia and Serbia are not. Still, proximity to the recipient does not seem to be a factor in explaining eastern EU democracy promotion activism. Consider that the most active democracy promoters differ in their proximity to their priority recipients: The Czech Republic has no direct nondemocratic neighbors; Slovakia borders just one such country, Ukraine, and has supported democracy in it as well as in two other nondirect neighbors (Serbia and Belarus); and Poland is an immediate neighbor to nondemocratic Ukraine and Belarus and has prioritized promoting democracy in both.

61 Interview with S. V., January 12, 2012.

62 Interview with O. Sh., Bulgarian activist, August 1, 2011; and interview with S. P., Bulgarian foreign policymaker, September 1, 2011.

63 Interview with S. P., Bulgarian foreign policymaker, September 1, 2011; and interview with N. M., Bulgarian foreign policymaker, July 23, 2011.

64 On the causal importance and the advocacy of Czech NGOs, interview with M. S., Czech activist, June 28, 2012; interview with K. P., Czech foreign policymaker, March 27, 2009; interview with K. C., Czech foreign policymaker, March 3, 2009; and Kucharczyk and Lovitt Reference Kucharczyk and Lovitt2008. On the different levels of Czech support for democracy abroad, see Herman and Piccone Reference Herman and Piccone2002; Kral Reference Kral2005; Fawn Reference Fawn2003; Galante and Schipani-Aduriz Reference Galante and Schipani-Aduriz2006.

65 “Foreign Policy,” in Global Report on the State of Society 2006 (Bratislava, Slovakia: Institute for Public Affairs, 2007), 32.

66 Ibid. Despite these continuities, and in spite of protests by Slovak NGOs, however, Bratislava’s democracy promotion in the rest of the world was inconsistent and often overshadowed by economic interests – a fact that demonstrates the limitations of these entrepreneurs’ advocacy.

67 Interview with O. Sh., Bulgarian activist, August 1, 2011.

68 Interview with S. V., Bulgarian activist, July 25, 2011; and interview with S. V., Bulgarian activist, January 12, 2012.

69 Interview with O. Sh., Bulgarian activist, August 1, 2011; and interview with S. V., Bulgarian activist, January 12, 2012.

70 Interview with D. K., Bulgarian activist, August 10, 2011.

71 Vachudova Reference Vachudova2005.

72 Interview with S. V., Bulgarian activist, July 25, 2011.

73 On Slovakia, see Duleba Reference Duleba2009; on the Czech Republic, see Kratochvil, Cibulkova, and Benes 2006; on Poland, see Andrew Rettman, “Polish Government Deeply Fearful of Russia, US cable shows,” EUObserver, August 12, 2010. Similarly, these countries differ in their geographic proximity to Russia and to other nondemocracies. The Czech Republic is farthest from Russia and borders only democracies. Slovakia is closer to Russia and borders nondemocratic Ukraine. Poland is closest to Russia and borders nondemocratic Ukraine and Belarus.

75 Interview with K. A., U.S. foreign policy representative, July 1, 2010; and interview with S. V., Bulgarian activist, July 25, 2011.

76 Interview with K. A., U.S. foreign policy representative, July 1, 2010; and interview with D. R., U.S. foreign policymaker, July 1, 2010. As Chapter 3 discusses, a more indirect form of support for the transformation of Bulgaria and Slovakia from recipients of democracy assistance to democracy promoters came in the form of U.S. sponsorship of the local civic democracy promoters. As discussed earlier, however, the United States has engaged with such activists from Bulgaria and Slovakia in comparable ways, yet the democracy promotion records of the two countries differ significantly.

77 Interview with R. P., U.S. donor representative, October 19, 2008.

78 International Centre for Democratic Transition, History of the International Centre for Democratic Transition, http://www.icdt.hu/about-us/introduction (accessed April 2010).

79 Horvath Reference Horvath, Kucharczyk and Lovitt2008.

80 The quantitative analysis further demonstrated that the strength of these entrepreneurs is not related to the other explanatory factors and that its impact is not contingent on any of the other explanatory factors.

81 Interview with R. S., Bulgarian activist, October 22, 2009; interview with D. K., Bulgarian activist, August 10, 2011; and interview with S. V., Bulgarian activist, July 25, 2011.

82 The most notable of these mechanisms is perhaps the so-called National Convent – a forum representing “all key segments of the Slovak society” in the policymaking process related to Slovakia’s EU membership. http://www.sfpa.sk/en/podujatia/narodny-konvent-o-eu/

83 Owen Reference Owen2010.

84 Sukma 2010; Brookings Institution 2010. Interview with R. S., Indonesian activist, March 20, 2013; and interview with R. R., Indonesian foreign policymaker, March 20, 2013.

85 Sukma 2010.

86 Brookings Institution 2010, 21–2.

87 Bunce and Wolchik Reference Bunce and Wolchik2011, 11.

88 On the “attribution of similarity” as a precondition for diffusion, see McAdam and Rucht Reference McAdam and Paulsen1993.

89 Lightfoot Reference Lightfoot2010.

90 Vachudova Reference Vachudova2005.