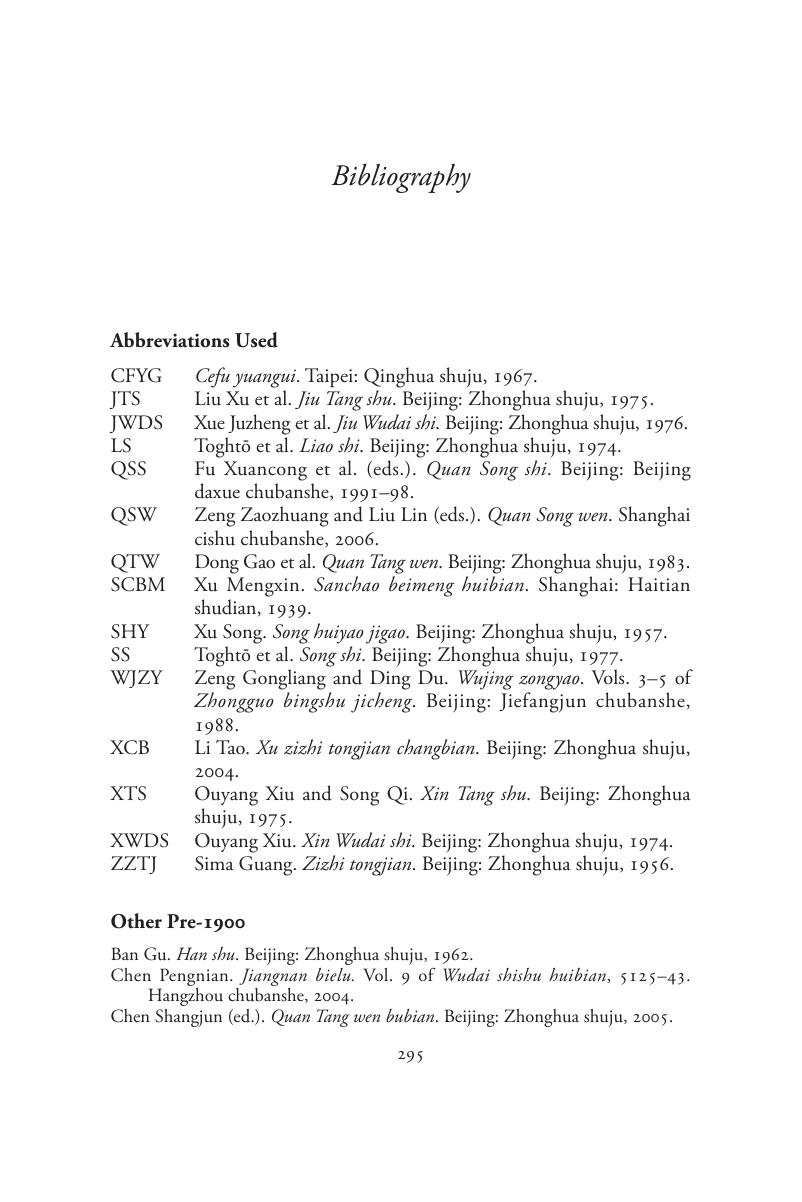

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 07 December 2017

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- The Origins of the Chinese NationSong China and the Forging of an East Asian World Order, pp. 295 - 318Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2017