14.1 Introduction

Following the 2016 peace agreement with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), the Colombian government focused on the crucial issue of how to finance the peace process, especially as oil revenues declined following rapid price decreases the same year. A structural fiscal reform was promulgated at the end of 2016 with the aim of rebalancing public accounts and addressing critical revenue challenges. Reform proposals focused on issues such as value-added tax (VAT) and tax evasion, yet long-running fiscal support to sectors such as mining received a free pass, even though the restructuring or elimination of subsidies might have unlocked an additional source of government revenue.

Colombia is one of the top five exporters of thermal coal globally, and the coal mining sector became a core pillar of the government’s economic-development policy during the 2000s. However, debate about the governance of the extractives sector (i.e. production of minerals, coal, oil and gas) has increased, notably around the real costs and benefits of mining, including large-scale coal mining. This debate has focused on the lack of transparency in the governance of mining and on the use of income generated by mining activities, as well as its environmental and social impacts. As a result, the mining sector, including coal extraction, suffers today from a growing legitimacy deficit in the eyes of the general public and, increasingly, local governments, who argue that they do not reap enough of the economic benefits (Long Reference Long2017).

This situation has contributed to a redesign of the mining policy (MME 2016) and has encouraged the government to become a member of the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) in an attempt to improve governance of the sector. Despite these changes, subsidies to the mining sector, including to coal mining, are increasingly a controversial subject in Colombia. There is, however, little explicit ‘subsidies’ language in policy debates or the academic literature, and the first two EITI reports submitted by the Colombian government (MME 2017; 2015a) make no mention of any subsidies to extractive industries.

To understand the resilience of fiscal support to coal mining in Colombia, this chapter explores the political dynamics behind the introduction and maintenance of various kinds of subsidies that support extraction. It focuses particularly on the subsidies regime associated with large-scale coal production. After a brief overview of the sector and its socio-economic importance, we introduce some of the key subsidies to large-scale coal extraction and then explore why and how these subsidies have been maintained. We discuss two key examples of subsidies – the Plan Vallejo and a royalty rebate – in more detail before drawing conclusions.

14.2 The Economic, Social and Political Roles of Coal Extraction in Colombia

Colombia produced roughly 85 million tonnes of coal in 2015, corresponding to 1.5 per cent of global production (BP 2017). More than 90 per cent of this is high-quality thermal coal from large-scale open-pit mines (SIMCO 2016). Compared to many other major coal producers, Colombia consumes little coal domestically: only 6.5 per cent, mainly for power generation and industrial use (IEA 2016). In 2015, virtually all the large-scale coal production in the La Guajira and César departments was exported (SIMCO 2016). Most of the coal consumed internally is produced by small- and medium-scale mines. Therefore, coal production serves other, more significant societal functions than ensuring power generation and energy security. This is reflected in the fact that the legal and institutional framework governing coal extraction is for minerals, whereas other fossil fuel extraction activities such as oil and gas fall under the country’s energy policy. Since 2000, coal extraction has been dominated by private companies, with three of them – Cerrejón, Drummond Ltd. and Prodeco – producing more than 76 per cent of all Colombian coal (MME 2015a).

In 2015, coal mining represented little more than 1.3 per cent of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) and 12 per cent of exports (MME 2016: 43). Yet the economic weight of coal extraction is particularly significant in the two main producing departments: in 2013, the industry contributed to 38 and 47 per cent of the regional GDP in the César and La Guajira departments, respectively (DANE–Banco de la República 2015a, 2015b).Footnote 1

The extractives industry in general has been a substantial contributor to the country’s public finances, accounting for about one-third of revenues in 2013 (Nieves Zárate and Hernández Vidal Reference Nieves Zárate and Hernández Vidal2016). Most of that comes out of the hydrocarbons sector; in 2015, the sector was responsible for three-quarters of the extractives industry’s contributions to the country’s public revenues via taxes, royalties and other types of financial compensation (MME 2017). For royalties alone, 82 per cent in 2014 came from oil and gas extraction, compared to 15 per cent from coal extraction and 3 per cent from other minerals (MME 2015b).

However, the wider economic benefits of large-scale mining have been the subject of growing criticism. Some highlight a lack of overall socio-economic development despite the extraordinary rents the commodity boom brought to the country (Rudas Lleras and Espitia Zamora Reference Rudas Lleras, Espitia Zamora and Salamanca2013; Torres et al. Reference Torres, Rocha, Melo and Peña2015); others worry about the potential negative macroeconomic effects of resource extraction (Torres González Reference Torres González2014). In a 2015 study commissioned by the Colombian Mining Association, 59 per cent of the interviewed inhabitants of mining municipalities said their well-being would improve if no further mining activities were developed (Arteaga Reference Arteaga2016).

Serious concerns over the environmental and human security impacts of large-scale coal mining have also been raised, focusing on community (voluntary or forced) relocation, indigenous and Afro-Caribbean communities’ rights (Múnera Monte et al. Reference Múnera Monte, Granados Castellanos, Teherán Sánchez and Naranjo Vasco2014) and air, water and soil pollution (Cabrera Leal and Fierro Morales Reference Cabrera Leal, Fierro Morales and Salamanca2013; Cardoso Reference Cardoso2015). Between 2000 and 2016, at least 179 social conflicts linked to the extractives sector (especially coal, gold and oil) have been documented (Valencia and Riaño Reference Valencia and Riaño2017). However, although 86 per cent of Colombians in 2016 thought that mining is destroying the environment, 78 per cent considered it essential for development (Rojas and Hopke Reference Rojas, Hopke, Henao and Espinosa2016).

Coal production also plays an important part in the country’s politics. Since the 1990s, the national government has based its economic policy on internationalisation and has embraced the extraction of natural resources as a main driver for development, thus facilitating the entry and operation of foreign financial and technological capital into the large-scale extractives sector (Vélez-Torres Reference Vélez-Torres2014). During this period, key mining actors reinforced their links with the national political elite (Sankey Reference Sankey2013), enabling the creation of a strong alliance between the national government, local elites and the mining sector under the administrations of Álvaro Uribe (2002–10) and Juan Manuel Santos (2010–18).

14.3 Subsidies to Coal Extraction in Colombia

As mentioned in Chapter 1, defining subsidies is a political exercise (see also Chapter 2). We draw on the definition from the Global Subsidies Initiative (GSI 2010a, 2010b), which builds on and expands the definition from the World Trade Organization’s Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures. The GSI thus defines subsidies as preferential treatment in all forms (financial and otherwise) provided to selected companies, to one sector or product when compared to other sectors or to sectors or products in one country when compared to other countries. It distinguishes the following categories of subsidies to fossil fuel producers: direct and indirect transfer of funds and liabilities, government revenue foregone, government-provided or government-purchased goods or services and income or price support.

Although incentives to coal extraction are rarely referred to as ‘subsidies’ in Colombia, the work by Rudas Lleras and Espitia Zamora (Reference Rudas Lleras, Espitia Zamora and Salamanca2013), Pardo Becerra (Reference Pardo Becerra2014; Reference Pardo Becerra2016) and Chen and Perry (Reference Chen and Perry2015) shows that there are a broad range of incentives to large-scale coal extraction, some of which can be considered subsidies. Many of these are tax incentives, a form of indirect support. The Directorate of National Taxes and Customs reported 179 tax discounts for the mining sector in 2014 (Parra et al. Reference Parra, Parra Garzón and Sierra Reyes2014: 31).

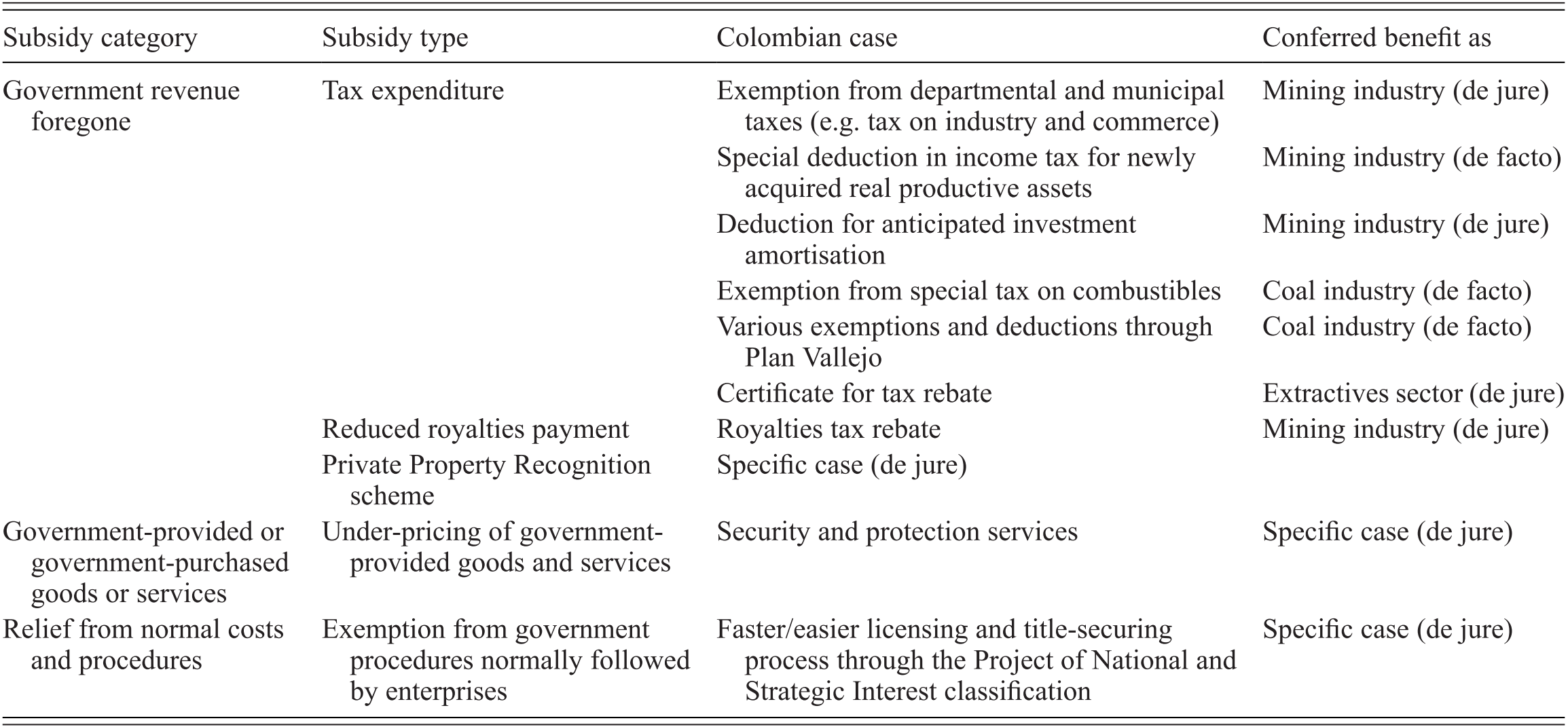

Here we provide a non-exhaustive account of subsidies from which the large-scale coal sector benefits (or has benefited from) to illustrate the diversity of mechanisms used to support the sector. While in many cases coal companies are conferred benefits because they belong to the wider mining or extractives sector, in some cases subsidies are specific to the coal sector. The following examples also show that while some of the subsidies are conferred through legal or administrative measures that target the (coal) mining or extractives sector explicitly (de jure), other conferred benefits are more general economic incentives that have ended up serving the interests of the mining or coal industry disproportionally (de facto). Table 14.1 summarises the subsidies according to the Global Subsidies Initiative classification.

Table 14.1 Examples of subsidies to coal Extraction in Colombia by subsidy category

| Subsidy category | Subsidy type | Colombian case | Conferred benefit as |

|---|---|---|---|

| Government revenue foregone | Tax expenditure | Exemption from departmental and municipal taxes (e.g. tax on industry and commerce) | Mining industry (de jure) |

| Special deduction in income tax for newly acquired real productive assets | Mining industry (de facto) | ||

| Deduction for anticipated investment amortisation | Mining industry (de jure) | ||

| Exemption from special tax on combustibles | Coal industry (de facto) | ||

| Various exemptions and deductions through Plan Vallejo | Coal industry (de facto) | ||

| Certificate for tax rebate | Extractives sector (de jure) | ||

| Reduced royalties payment | Royalties tax rebate | Mining industry (de jure) | |

| Private Property Recognition scheme | Specific case (de jure) | ||

| Government-provided or government-purchased goods or services | Under-pricing of government-provided goods and services | Security and protection services | Specific case (de jure) |

| Relief from normal costs and procedures | Exemption from government procedures normally followed by enterprises | Faster/easier licensing and title-securing process through the Project of National and Strategic Interest classification | Specific case (de jure) |

In terms of revenue foregone, the coal sector (and the rest of the mining industry) benefits from an exemption on departmental and municipal taxes. This implies that departmental and municipal governments are prevented from generating additional tax income from coal exploitation and exploration (Pardo Becerra Reference Pardo Becerra2014). The mining industry, including coal, also benefits from a deduction for anticipated investment amortisation: mining exploration and development expenditures are written off within at least five years, and expensing of failed explorations is allowed.

Between 2004 and 2011, the sector disproportionally benefited from a special deduction in their income tax of 30 per cent from the investment value of newly acquired real productive fixed assets (Rudas and Espitia Reference Rudas Lleras, Espitia Zamora and Salamanca2013). When introducing this measure in 2003, President Uribe – recognising it could incur significant fiscal costs – framed it as a way to stimulate foreign direct investment and employment in a national context marked by insecurity and infrastructure deficits (Presidencia de la República Reference Pizarro Leongómez and Gutiérrez2003). However, because it proved both costly and ineffective (Galindo and Meléndez Reference Galindo and Meléndez2010), this measure was abandoned when President Santos came to power as part of an effort to improve tax collection efficiency.

Further, a 1959 measure to stimulate exports, known as the Vallejo Plan, allows Colombian companies to claim total or partial exemption from customs duties (such as tariffs and VAT) when they import raw materials, intermediate inputs, capital goods and spare parts that are destined for the manufacture of export goods. The Vallejo Plan was intended to incentivise the manufacturing industry and promote non-traditional exports. However, it ended up disproportionally favouring the coal sector (see Section 14.5). In addition, the 2016 fiscal reform reintroduced for the extractives sector the Certificate for Tax Rebate, a credit that can be applied to taxes on income, custom duties and other taxes.

Besides the tax expenditures just described, large-scale coal mining has also benefited from an exemption from special taxes because of its geographical proximity to Venezuela. In 2001, a tax relief measure was introduced to support the economy of border areas, exempting liquid combustibles distributed by the national oil company Ecopetrol from VAT, import duty and the ‘global’ tax on gasoline and diesel. This measure was initially supposed to be temporary but was extended and modified on several occasions. In 2007, the exemption was restricted to big consumers, or those consuming on average more than 20,000 gallons a month. As a result, there were fewer beneficiaries from the measure; however, one of these was the large-scale coal industry. The subsidy was eliminated in 2010 as part of tax reform in the Santos administration.

The coal sector, like the rest of the mining industry, is also eligible to deduct royalties from its income tax (see Section 14.5). This measure cost the Colombian state more than COP 13 trillion (approximately USD 6.2 billion) between 2006 and 2012 (Congreso de la República 2014).

Some coal companies benefit from special conditions under the Private Property Recognition scheme, a legal provision establishing the royalty rate at 0.4 per cent or more of the production value. This compares with the general minimum rate of 5 per cent of the mining pit revenue for companies extracting up to 3 million tonnes annually; the rate is 10 per cent for companies extracting more than 3 million tonnes annually. This special regime applies to certain mining titles issued by the state to private individuals during the nineteenth century (intended to boost mining). It did not include environmental, technical or economic obligations until 2011, when the 0.4 per cent minimum royalty rate was introduced through a ruling by the Constitutional Court. Three of the 55 existing Private Property Recognitions are for coal (Pardo Becerra Reference Pardo Becerra2012), including one for a title owned by Cerrejón (Cerrejón 2010).

Regarding benefits from the provision of goods and services below market value, the mining sector receives special security and protection services by the Colombian government (CODHES 2011; Vélez-Torres Reference Vélez-Torres2014). This can take the form of providing information, escort and backing, as well as designing security protocols and managing dynamite stocks on site. Companies appear to be contributing to part of these costs but not all of them (Glencore 2015). This type of relationship between companies and the state is established formally in agreements between the Ministry of Defence and the companies themselves (Sarmiento Reference Sarmiento2008). However, these contracts are mostly kept secret under the argument of preserving national security (Tierra Digna 2015). In 2011, about 12,000 army and navy personnel were reported to be protecting extractive operations (Mining Colombia 2011).

In the category of relief from normal costs and procedures, an example of a subsidy is the use of the Project of National and Strategic Interest classification. Private projects that are deemed strategic for the social and economic development of the country are eligible for special procedures relating to environmental licensing and land ownership applications (González Espinosa Reference González Espinosa and Isaza2015). The Colombian Ministry of Mines and Energy lists four coal Projects of National and Strategic Interest, including mines operated by Cerrejón, Prodeco and Drummond Ltd. (MME 2018).

These are only some key examples that illustrate the diversity of subsidies to the (coal) mining industry and the mechanisms used to confer them. However, it is possible that coal mining companies benefit from additional subsidies through special conditions negotiated directly in the contracts they signed with the state (Tierra Digna 2015).

14.4 The Power Dynamics Behind Coal Subsidies in Colombia

Understanding why subsidies were originally introduced is essential for identifying the opportunities and challenges for their reform. Here we turn attention to the political strategies used by a particular coalition of actors in Colombia – comprising the national government, coal extraction companies and other mining companies – to introduce and maintain subsidies that benefit coal extraction. As Victor (Reference Victor2009) highlights, the politics of subsidies include both their demand from typically well-organised groups of private actors and their supply by government in the pursuit of specific policy goals (e.g. attracting foreign investment or fostering industrial development). The introduction of the special income tax deduction for investment in real productive fixed assets by President Uribe in 2003 (see Section 14.3) is an example of the latter.

Various authors have conceptualised the relations between policymakers, public officials and incumbent companies as an alliance interested in maintaining the status quo and resisting fundamental change (Geels Reference Geels2014; see Chapter 4). One example is the ‘minerals-energy complex’ in South Africa, which describes capital accumulation of fossil fuels companies backed by policymakers (Fine and Rustomjee Reference Fine and Rustomjee1996; see Chapter 13).

Building on Geels (Reference Geels2014) and Kern (Reference Kern2011), the approach we take is to explore the political strategies and factors behind coal subsidies by analysing different forms of power: discursive, instrumental and institutional. ‘Discursive’ forms of power refer to processes of elaborating and making public discourses, which shape not only what is being discussed (thus setting agendas) but also how issues are discussed (see the discussion of ideational factors in Chapter 1). A better understanding of how ideational factors influence the introduction, maintenance and removal of subsidies can be gleaned by examining how those advocating for or offering subsidies frame coal extraction and the benefits or ‘necessity’ of government support. ‘Instrumental’ forms of power refer to cases where actors use resources (e.g. positions of authority, money, access to media, personnel and networks) to achieve their goals and interests (see also Chapter 1). ‘Institutional’ forms of power refer to how elements embedded in political cultures and governance structures (or socio-political factors) are mobilised or contribute to shape the subsidies regime (see also Chapters 1 and 4).

14.4.1 Discursive Forms of Power

Exploiting natural resources has been a key pillar of modernisation efforts in Latin America since the 1950s and remains an essential component of economic development models across the region, notably with the global boom in commodity prices of the 2000s (Veltmeyer and Petras Reference Veltmeyer and Petras2014). The relationship between extraction and economic development has been a key narrative used by the region’s governments to legitimise the existence of incentives to the extractives sector.

In Colombia, the development model shifted noticeably towards the extractives sector during the Uribe administration (2002–10). A special role in fuelling economic development was given to both hydrocarbons and minerals extraction. The development of the energy and mining sectors, together with the democratic security policy,Footnote 2 was seen as the path for Colombia to become one of the leading economies in Latin America by 2019 (Insuasty Rodriguez et al. Reference Insuasty Rodriguez, Grisales and Gutierrez León2013). The government’s discourse on the special role of the mining sector in Colombia’s economic development was accompanied by statements on the need for foreign investment to fully develop Colombia’s mining potential – and therefore on the need to increase the country’s competitiveness by providing incentives to foreign investment.

During the first administration of Juan Manuel Santos (2010–14), resource extraction maintained its central role and was framed as one of the ‘locomotives of development’ in the National Development Plan (NDP 2010). In this period, the government also increasingly used the concept of ‘responsible mining’ (Presidencia de la República 2013; Santos Calderón Reference Santos Calderón2014). Since 2015, however, this metaphor was abandoned in response to the economic and legitimacy issues of the mining sector. A new ‘peace’ frame was introduced: the national government now justifies the importance and incentives given to the extractives sector based on its expected contribution to funding the peace process and its associated social programmes (González Espinosa Reference González Espinosa and Isaza2015).

This new frame not only ensures that the extractives sector is perceived as a key partner, or even an enabler, of the country’s new development era after the peace deal with FARC, but it also leads to distorted public perceptions about the actual importance of coal in Colombia’s economy and its actual contribution to the state’s income, as well as to the diffusion or suppression of some of the concerns raised about the sector’s socio-economic impacts. As the leading mining industry, coal has benefited from being included in a broader mining and energy package that levels out the particularities and differences between minerals and hydrocarbons. For instance, the differences in terms of revenues generated and scope of payments between the hydrocarbons and the mining sector are considerable. The extractive sector paid COP 35 trillion (USD 18.5 billion) to the Colombian state in 2013, but only COP 2.3 trillion (USD 1.2 billion) was from the mining sector. Of that, 85 per cent was paid by the three main coal companies, Cerrejón, Drummond and Prodeco (MME 2015a).

14.4.2 Instrumental Forms of Power

A key political factor behind the maintenance of subsidies to the coal sector in Colombia is the strengthening of a broad constellation of actors that include mining business associations and others that benefit from the subsidies regime. Traditionally, lobbying through business associations has been an effective way for mining companies to secure significant subsidies for the sector, as described in Section 14.5. Until 2014, there were three main business associations defending mining interests: the Colombian Chamber of Mining, the Association of Large-Scale Mining Sector and the Miners’ Association (Asomineros). However, they combined to create the Colombian Mining Association in order to improve bargaining positions and communication to the general public. This fusion implies that the Colombian Mining Association is now representing a very large portion of the mining industry, articulating and representing interests from operators, producers and goods and services providers to the sector.

As was the case with framing strategies, coal producers have partnered with the rest of the mining industry to benefit from a more powerful position when negotiating with the government. However, this partnering strategy also creates additional challenges for the large-scale coal sector. While facing its own reputational challenges, it now also indirectly faces criticism that was traditionally linked to other mining subsectors, such as the disastrous environmental impacts of mercury use in gold extraction. While the coal sector’s strategy had been to keep a low profile to reduce financial and operational risks deriving from social acceptance issues (González Espinosa Reference González Espinosa2013), large companies are now increasingly engaging in communication activities, using the media to respond to accusations and improve their image.

The large-scale coal sector has also been involved in important partnership initiatives with public institutions aimed either at improving the performance of the sector (e.g. the EITI) or at engaging in social programmes (e.g. Alianza Social, a programme through which mining companies made voluntary commitments with the National Agency for Overcoming Extreme Poverty). These initiatives have been useful platforms for the sector to interact with key policymakers at the national level. At the local level, coal companies and political leaders have historically been closely linked, including through the revolving-door channel (when policymakers join industries they used to regulate and vice versa) or through political campaign financing (Transparencia por Colombia 2014). For example, several former governors and other local political leaders have had a long-standing relationship with Cerrejón, from when the state still had a stake in the company (González Espinosa Reference González Espinosa2013).

14.4.3 Institutional Forms of Power

One key element in understanding government support to coal mining, including subsidies, is the historical legacy of internal conflict and the Colombian state’s weakness and lack of legitimacy among large sections of the population. In 1991, the country underwent a constitutional reform that sought to increase the presence of the state by devolving fiscal and political power to lower levels of government and expanding basic social services (Torres del Río Reference Torres del Río2015). These measures, together with defence efforts to deal with drug trafficking, paramilitary activities and guerrilla warfare, required considerable resources. The state thus needed revenues urgently and introduced successive fiscal reforms that would prioritise rapid revenue production (or limit specific expenditures such as regional transfers) instead of tax efficiency, a situation that has prevailed since the 1990s despite several attempts at structural reform (Olivera et al. Reference Olivera, Pachón and Perry2010). Indeed, royalties became one of the most important public revenues in resource-rich regions. In La Guajira, royalties reached an annual average of USD 23.6 million between 1985 and 2004; this amount increased along with production between 2005 and 2007 to an annual average of USD 105 million (FCFI 2009: 10).

At the same time, conditions established in loan agreements with the International Monetary Fund in 1998 and 2003 led to a series of privatisations and restructuring of the state. Compared to other Latin American countries, where structural adjustment and pro-market economic policies aimed to reduce the role of the state, Colombia intended to use these measures to strengthen the state’s administrative functions (Flórez Enciso Reference Flórez Enciso2001). This pursuit of short-term revenues partly explains why the economic policy of the 2000s prioritised the extractives sector and introduced incentives for mining. The thinking was that development of this sector would deliver a steady flow of rents for the state, as long as conditions were made attractive enough to foreign investors (Caballero Argáez and Bitar Reference Caballero Argáez and Bitar2015).

Another key dimension here is the fragmentation of political parties and lack of programmatic discipline, a result of modifications to the Constitution of 1991 concerning political parties’ representation in the Congress and also of powerful lobbying by interest groups (Pizarro Leongómez Reference Pizarro Leongómez and Gutiérrez2002). These political dynamics have favoured the expansion of nominal tax rates while simultaneously expanding tax exemptions (Salazar Reference Salazar2013).

14.5 Political Factors in the Introduction, Maintenance and Removal of Subsidies

This section describes how the political dynamics introduced earlier have shaped the establishment, maintenance and/or removal of two subsidies that have highly benefited the Colombian coal industry.

14.5.1 Plan Vallejo

Plan Vallejo was introduced under the Alberto Lleras administration at the end of the 1950s in response to a deep economic crisis characterised by a drop in the price of coffee, a crisis in foreign trade, structural unemployment and a decades-long agrarian conflict. The Plan, combined with tighter currency controls and import restrictions, aimed to boost the transformation of imported raw materials and subsequent export, as well as to expand Colombia’s export capacity (Garay Salamanca Reference Garay Salamanca1998). This effectively represented a shift from the import-substitution industrialisation model to a new model based on the promotion of non-traditional exports. As a result, non-coffee exports started to increase exponentially after the 1967 modifications to the currency exchange policy (Amézquita Zárate Reference Amézquita Zárate2009). This framing remains today: the Minister for Trade announced an expansion of the Plan at the end of 2016 with the aim of increasing exports from sectors other than mining and energy (Lacouture Reference Lacouture2016).

The 1960s economic policy change was also the result of a significant shift in the country’s politics. At that time, a political agreement known as the National Front (1958–74) had emerged after years of bipartisan violence and military dictatorship, where the two main political parties (the Liberal and Conservative Parties) alternated power during four presidential terms. Under these special political circumstances, clientelism deepened (Leal Buitrago and Dávila Ladrón de Guevara Reference Leal Buitrago and Dávila Ladrón de Guevara2010), bringing economic elites together and safeguarding the interests of the emerging bourgeoisie and old landowners around the patrimonial order and the generous profits from coffee exports and industrial production (Leal Buitrago Reference Leal Buitrago and González1996).

Although the Plan has gone through a series of modifications since its introduction, especially regarding its administration, its main terms are still being applied five decades later. However, the definition of ‘non-traditional exports’ has not been adjusted over time, even as the actual export mix has changed, and as a result – against the spirit of the initiative – the industry benefiting most from the policy has been coal mining. Along with the internationalisation of Colombia’s economy, the share of coal exports under Plan Vallejo increased from 3.2 per cent in 1985 to 27.2 per cent in 1990 (Garay Salamanca Reference Garay Salamanca1998). In 2015, over one-third of the exports made under the Plan consisted of coal (Granada López et al. Reference Granada López, Zárate Farias and Sierra Reyes2016).

The maintenance of Plan Vallejo was called into question by the World Trade Organization, whose Trade Policy Review Body identified the Plan as an export subsidy in 1996 and reported it to the Committee on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures (see also Chapter 7). Colombia was given until 2003 to phase out Plan Vallejo and other export-related incentives. Thanks to ‘heavy diplomatic artillery’, the country was granted a three-year extension (El Tiempo 2002). After further negotiations, Colombia managed to keep the Plan for raw materials and services, although it had to limit the scope with regard to capital goods and spare parts. Subsequently, during negotiations about a free trade agreement, the United States initially requested elimination of the Plan for raw materials. Once again, however, Colombia managed to keep it rolling; after negotiations, the trade agreement allowed Plan Vallejo to remain in place (El Tiempo 2005).

Pressure on the Plan not only came from outside but also from inside the country. In 2004, at a Presidential Summit of the Andean Community, President Uribe suggested dismantling Plan Vallejo if other Andean countries would do the same with similar instruments. This generated strong opposition not only from the coal sector but also from other export-oriented sectors that rely heavily on the Plan’s incentives to maintain their competiveness (Correa Reference Correa2004). This suggests that an important factor for the maintenance of the Plan is support and lobbying from other industries, such as flowers and textiles production, through broader business associations such as the National Association of Exporters (Analdex).

In summary, framing and instrumental strategies have been essential in ensuring that the industry keeps the conferred benefits despite both internal and external pressures. The strength of the discourse around the contribution of Plan Vallejo for Colombia’s industrial development, along with effective lobbying from a coalition of exporting industries, has enabled the Plan to remain legitimate in a different economic model than the one in which it originated. This example also illustrates how a policy that was not designed as a subsidy to the coal sector when it was introduced became one as a result of changes in the domestic and global economic context.

14.5.2 Royalties Rebate

In 2005, a decision by the National Tax and Customs Directorate allowed mining companies to deduct the royalties they pay from their income taxes. This measure was introduced in response to a formal request by Carlos Alberto Uribe, who was then the president of Asomineros (and is not a close relative of the ex-president). The business association argued that royalties are a cost for companies – although the Colombian Constitution establishes that royalties constitute a mandatory compensation to the state generated by the exploitation of non-renewable natural resources.

The decision marked a significant change in the institution’s interpretation of Colombia’s tax law, since it had itself responded negatively to the same request on two earlier occasions, in 1998 and 2004 (Proyecto de Ley 071 2014). In 2005, however, the National Tax and Customs Directorate argued that mining companies should be given the same treatment as the national oil company Ecopetrol and be allowed to discount royalties from their income taxes.

There have already been at least four attempts to remove the subsidy since its introduction: in November 2011, when the Senate discussed the government take from mining activities; in 2012, when the Liberal Party led a proposal to reform the royalties system; in 2013, when a group of congressmen and academics submitted a simple invalidity action to the State Council, and again in 2014 through a legislative proposal from Senator Julio Guerra Soto. The lawsuit filed in 2013 was ultimately successful. In October 2017, the State Council canceled the measure (Morales Manchego 2017).

This last example not only illustrates how powerful and well-organised private interests contributed to the introduction of a key subsidy to coal production in Colombia through instrumental strategies, but it also shows how the mining sector, dominated by coal companies, has made use of institutional means to get new subsidies in place. It also raises questions about accountability and democracy in relation to the subsidy’s introduction; despite the subsidy’s significant impact on the state’s spending capacity, and resulting indirect impacts on the Colombian population’s well-being, its adoption was made by a non-representative authority.

14.6 Conclusion

The Colombian case illustrates the diversity of subsidies that are provided to fossil fuel production. It provides insights into the varied and innovative framing strategies used by producers and the governments to justify the existence of fiscal incentives. It also suggests that a powerful actor coalition exists in Colombia beyond the coal sector itself, including not only other minerals producers but also the national government and, in some cases, other export sectors. While relying mainly on traditional instrumental strategies, the coal industry has also made efforts to develop innovative framing strategies while relying on institutional support from the national government to maintain existing or obtain new subsidies.

In Colombia, a complex set of objectives is being pursued by the government, not all of which relate to the energy or natural resources sectors. The Colombian example highlights issues of democratic legitimacy and accountability in the establishment of subsidies, as evidenced by the example of the royalty rebate. When the Colombian Congress discussed the 2016 fiscal reform, there was significant debate about a VAT increase – a measure known for placing a high burden on the poorer segments of the population – but little was said about sectoral subsidies, such as those described here benefiting coal mining. The Congress did not discuss the actual socio-economic benefits of such subsidies or the opportunity cost of maintaining them. This is nevertheless a crucial matter within the context of the peace agreement’s implementation. The process needs significant public resources, and peace is contingent on the well-being of and economic opportunities for Colombians in rural areas, which depend on how public resources are used.

The Colombian case offers insights into how historically inherited political and social factors have influenced the governance of the sector, including the provision and maintenance of subsidies. Many of these influential socio-political factors are shared with the rest of Latin America, as a result of the continent’s historical processes of integration in the global economy. A historical comparative assessment of the Colombian case with other Latin American fossil fuel and minerals producers – such as Brazil, Chile, Peru and Venezuela – would provide interesting perspectives on how domestic and global political and economic factors have interacted to shape the current subsidies regime for fossil fuel extraction in these countries. Understanding these interactions will be essential to effectively combine domestic and global strategies for reforming fossil fuel subsidies.