The idea of Rome and the idea of power are inextricably linked. Rome’s empire lasted longer than any other except China’s and, though often surpassed in size by later empires it was rivalled in ancient times only by the Persian Achaemenids and the Han dynasty in China. We may wonder what human being ever exercised significantly greater power than the more effective kind of Roman emperor, Augustus, say, or Trajan.

But what is power, and what are the best ways of analysing its workings in a historical society? These questions were never easy, and since Foucault made such ‘promiscuous’ use of the term,Footnote 1 the complexities have increased still further. No concept, perhaps, is more pervasive or protean (not to say vague) in current intellectual discourse. Half of the non-fiction book titles now being published seem to contain the word. And the modern concept of ‘power’ commonly combines both raw physical power (German Macht) and institutionalized power (German Herrschaft).Footnote 2 Nonetheless power exists all right, the power of human beings to determine the actions and experience of other human beings, and its sources and characteristics in any given society can be analysed.

An added difficulty in studying Roman power is that its modern historians seem to be especially liable to power-worship. This is in fact the main obstacle, apart from sheer foolishness, that has made it difficult for people to write the history of how the Roman Empire was put together in the first place. One symptom of this subservience is the reluctance that scholars sometimes show to call Roman republican imperialism ‘imperialism’,Footnote 3 a bizarre evasion that need not detain us for long (I shall say a little more about it later: p. 36). And when we come to late antiquity, the related problem of ‘vicarious identification’ identified by Brent ShawFootnote 4 seems if anything to intensify: contemporary historians commonly seem to consider the empire of Justinian to have been somehow ‘our side’, which leads to all sorts of distortions. Far from being an impersonal matter, the rise and fall of the Roman Empire engages strong feelings, even now.

The worship of power can maintain a certain level of respectability because it merges into the fascination with power that is very widespread if not universal: how it is gained and lost, how it is abused and resisted – these are the themes of a large part of our myths and histories. And since we are inevitably subjected to power, even if we are born to be the emperor of Rome or China, or the Sultan of Brunei, it is just as well that we should try to understand it.

The questions that this book sets out to answer are the following. Why in the first place did Roman power spread so widely and last so long? External factors such as the relative weakness of many neighbouring peoples had major effects, but no one will doubt that internal factors were also crucial. Some of these were geographical, demographic, or economic, but power relations within the Roman world probably made a great deal of difference too. So how should we characterize these relations? How much power of various kinds – political, legal, economic, psychological, discursive, or any other kind – did some inhabitants of the Roman world have over others? And I shall implicitly be asking whether we help ourselves as historians if we take the tempting analytic course and distinguish political power, legal power, economic power, and so on, even though we know that in pre-modern societies most kinds of power were often concentrated in the hands of a single elite and its agents.

What in the end went wrong, wrong that is from the Roman point of view? The Roman Empire still in the age of the reconqueror Justinian (ad 527–65) extended from one end of the Mediterranean to the other, finally ceasing to be an empire only under the rule of Heraclius (ad 610–41). Why did it fail to maintain its place in the world, and what were the internal power structures that accompanied that failure?

Any worthwhile analysis of power in the Roman world, however brief, has to be three-dimensional. It has to capture the dimension of national power, the domination by the gradually expanding group of those who called themselves Romans over the rest of the empire’s inhabitants, together with their power along the empire’s edges and beyond them. It must also capture the dimension of social differentiation or social class, without underestimating the importance of the political institutions and structures, or of slavery, or of gender power, or of power within the family.

Finally it must take full account of time and of the discontinuities as well as the continuities to be encountered in a thousand years or so of more or less accessible Roman history, from say Camillus (the shadowy military hero of the 390s and 380s bc) to Heraclius. There are strikingly few Roman histories – in fact, almost none – that attempt to cover the whole arc of Roman imperial history. Not only is it a unitary subject, but the earliest and the latest phases greatly illuminate each other, and we would have been spared a good deal of implausible story-telling about the sixth- and seventh-century ad Roman Empire if its historians had paid more attention to the Republic, and vice versa. And there were many continuities, most notably slavery: ‘it is likely that more than 100 million people were enslaved in the millennium during which the Roman empire rose and was eclipsed’.Footnote 5

Some readers will be startled to see Roman history divided into three such long periods.Footnote 6 This is programmatic. We normally end our Roman histories too early, in many cases much too early. When did the Roman Empire come to an end? Not in any case, as many historians continue to imply, with the reign of Constantine (ad 312–37), or when Rome was captured by the Visigoths (410). The latter event was a symptom but not by any means the end, for the centre of gravity had shifted from west to east between 324 (the foundation of a new capital at Constantinople) and the early fifth century. Montesquieu [Figure. 1.1] already knew very well not to make this error.Footnote 7 Just as Rome had gradually grown stronger in the fourth and third centuries bc until it was clearly an empire, so the Roman Empire gradually grew weaker from the late fourth century onwards. But the enterprise survived much longer as an empire. Some treat the fall of the emperor Maurice in ad 602 as the empire’s end.Footnote 8 The only significant exception to premature endings in recent anglophone historiography is a text-book by David Potter.Footnote 9 But there was an end: after the Battle of the Yarmuk (636), when the Muslim Arabs deprived the Byzantine emperor of the vital Syrian provinces, it begins to make much more sense to see Byzantium not as an empire in any proper signification of the term but as one state among a number of others that covered western Eurasia and the Mediterranean. Antioch fell to the Muslims in 637, Jerusalem in the same year, Alexandria in 641 (but it was only in 698 that they destroyed Carthage), and before very long the Umayyad Caliphate was larger than the Roman Empire had ever been.

Figure 1.1. Charles de Secondat, Baron de Montesquieu, whose book Considérations sur les causes de la grandeur des Romains et de leur décadence (Amsterdam, 1734) was the first important historical analysis of the Roman Empire in modern times

By 636 the Roman Empire had few Latin-speaking subjects, but that is a secondary issue: the sixth- and seventh-century Byzantines believed that they were Romans and that their territory was Romanía (hence John the Lydian naturally started his On the Magistracies of the Roman People – his people, even though he was born in western Asia Minor – with Romulus),Footnote 10 and their continuous history entitled them to that belief. After the disastrous events of 636–42, however, the question is whether the Byzantine Roman Empire was still powerful enough to be counted as an empire – and it did not fit that description again for more than 300 years, not in fact until the early eleventh century and the last years of the emperor Basil II. The years between 636 and the failures of the emperor Constans II (641–68) should be recognized as the real end of the Roman Empire.

As to why serious Roman historians virtually never cover the entirety of Roman history, there are more and less obvious reasons. The most obvious is that it is very difficult. Almost everything changes, not only the sources and the material culture, but the principal language and the dominant religion. But that is a challenge not an excuse.

Having determined the chronological limits, the historian should try to decide where the major discontinuities lie. The years ad 16 and 337 seem to me the best choices, all the more so because they are to some extent counter-intuitive. Neither date represents an obvious revolution. I choose 16 because it was in that year that the emperor Tiberius slowed down the expansion of the Roman Empire – how long-term a change he expected this to be we cannot tell –, and because he, more than anyone, finished off the old aristocracy and made the monarchy absolute (not that I would want to minimize the tyrannous nature of the regime of Augustus). I choose 337 because, although the house of Constantine continued to rule for another twenty-six years, internal political cohesion began to disintegrate at once, and it is in the next generations that we may reasonably look for the emergence of the factors that led to the collapse of the Roman Empire in the west.

A great advantage of the long view taken here is that, as I suggested above, the distinctive aspects of the periods in question will stand out more clearly. Cross-cultural comparisons are, rightly, an important part of the current historical agenda, but we should not neglect cross-period comparisons when, as in the case of Roman history, the imperial, geographical, and environmental contexts remain the same or are broadly similar.

Nonetheless a history such as this will be notably more valuable if it takes at least some notice of other comparable empires. It can for instance be safely assumed that most empires maintain their power with the help of co-opted local elites – so what was specific or exceptional about the ways the Romans did that? A number of empires have structured power relations by means of complex systems of law, so why is it that we look upon the Roman Empire as the great historical example of this phenomenon? If we want to answer such questions, or questions about the rise and decline of the Roman Empire – questions about causation are the most important ones of all –, we need to consider other large and/or long-lasting empires, such as those of Britain and China. This is becoming a received doctrine. It is less commonly observed that if we are to understand the rise of Roman power we also need to study the Romans’ less successful rivals (why no Spartan empire, why no Etruscan empire?), and other less successful ancient-Mediterranean empires whose affairs are relatively well known to us; that means above all the empire of the Athenians.

Yet this is not a comparatist account, in the sense of a full-blown attempt to delineate a set of actual or potential imperial systems. Others have recently attempted comparisons between Rome and China, and between Rome and the Mughals. The Byzantine and Ottoman empires offer ample scope here. But my intent is to make use of comparisons that throw bright light on the Romans, and in particular on the reasons for historical changes, rather than to list similarities and ‘divergences’ or formulate universal historical laws.Footnote 11

And the most meaningful comparisons of all, so I maintain, juxtapose one Roman period against another; taking an unusually inclusive time-frame, more than ten centuries, is therefore a great advantage – and we can say at once that Rome’s republican successes as an imperial power can teach us things about the late-antique Roman Empire’s military failures, and vice versa. In particular, the contrast between the mid-republican army on the one side and the armies that served the emperors Honorius, Maurice, Phocas, and Heraclius on the other is intense.

A system of law is an abstraction, and that will remind us that abstractions as well as people and groups of people exercise power: the Roman Empire itself is an abstraction, the Roman state is an abstraction, so is any given social class, so is religious belief. The ideas conveyed by images and buildings can have power, so that it has become natural to speak of the power of the images themselves. Traditions can have power, as mos maiorum (‘ancestral custom’) did at Rome. So can rhetoric. Emotions – anger, for instance – can have power, as historians have increasingly come to recognize. Stoicism, arguably the most powerful ideology of the high Roman Empire, is another abstraction. Slogans can exercise power too, especially perhaps if their meaning is highly unstable – libertas is the extreme Roman example.Footnote 12 It used to be widely held that ideas exercised relatively little power in the Roman world, but fewer now believe this. So part of our task is to decide which abstractions truly altered behaviour.

To ward off excessive abstraction, however, I intend to illustrate the big historical processes, as much as possible in this limited space, with the behaviour of individuals. Some of these will be the obvious men of power who could sway the power of the state, and might, according to circumstances, bestow or withhold a livelihood, social position, freedom or the right to go on living. But not all powerful individuals were emperors or senators, for it is a characteristic of power that even in the most centralized state it is extremely diffuse: the village policemen and the petty tax-gatherers of the Roman Empire exercised a sort of power, as well as the mighty dignitaries, and even within a system of brutal slavery, power of various kinds could in certain circumstances come into the hands of the unfree. One historian says that even Christian visionaries had power in the high Roman Empire,Footnote 13 and in a limited sense that is clearly true.

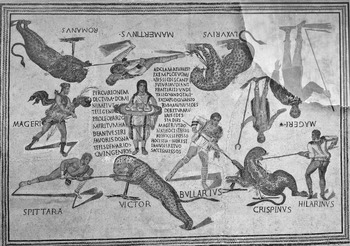

Here [Figure. 1.2] is an illustration of local power: a third-century ad mosaic floor from Smirat in coastal Tunisia commemorates a venatio, that is to say a massacre of wild animals, a favourite Roman sport. There is text as well as pictures, and the cries of the spectators are imagined: ‘…when was there ever such a show (munus)?… Magerius pays. That’s what it is to be rich, that’s what it is to have power (hoc est posse)…’.Footnote 14 This Magerius, who is otherwise unknown, has wealth and local power (how much? in virtue of what exactly?). But others have power at Smirat too, not only the local fat cats like Magerius, but also the spectators to some extent, and also the ‘hunters’, the Telegenii, who provided the leopards and killed them in the arena.

Figure 1.2. This mosaic from Smirat (Tunisia) shows a venatio or slaughter of wild animals, in this case leopards, which was funded by the local magnate Magerius. It explicitly emphasizes his (local) power (see the text). Mid-third century ad. Museum of Sousse, Tunisia

Local power is indeed something of an additional challenge for this project. Dorotheos of Gaza (sixth-century ad, very late in this history) wrote rhetorically that a man who was number one at little Gaza would be rated below the great men at nearby Caesarea, and would count as a mere outsider [paganos] in Antioch and as a poor man in Constantinople (Didaskaliai [Instructions] 2.34)Footnote 15 – the difference, roughly, between village, town, city, and capital. This was an obvious if imprecise truth, but for much of Roman history the story was still more complicated, chiefly because the people who owned the land and other assets in the small places were very often the wealthy from the capital and the cities.

How then did the Romans themselves, at various periods, think of the workings of power? We shall see going forward. But two questions are worth posing immediately.

(1) Was Roman thinking about power exceptionally legalistic? The natural answer seems to be yes: the Republic expressed many of the major changes in its own evolution in the form of laws, and there was a strong strain of legal pedantry in its public life. Technically proficient and politically influential experts on law were a constant feature from the first century bc onwards. But it may be that the intense attention given to the delimitation of potestas (legally or constitutionally established power) and imperium (the right of certain high officials to get their orders obeyed)Footnote 16 was a result not simply of an especially legalistic mentality, but of the particular nature of the Roman social-political system itself. Under the Republic this system was aristocratic – the inner circle of power was indeed hard to enter – and even under the Principate it was socially exclusive; but at the same time the ordinary citizens had specific rights,Footnote 17 and for centuries these were jealously guarded. Legal status very often mattered, and this continued to be true in the later empire. Definitions were necessary.

(2) A considerable amount of what Romans said and wrote about power consisted of myth-making, and we ought to identify the prevailing myths. One – the myth that Rome was a citizen democracy – is illustrated by a passage of Cicero, On Laws: speaking of the relationship between the citizens and the magistrates, he wrote that ‘he who obeys ought to hope that one day he will command (imperaturum)’ – which for most Romans would have been the wildest delusion.Footnote 18 Two centuries later, Aelius Aristides (To Rome 90; cf. also sect. 60) could solemnly, though perhaps not without some private irony, tell the Romans that their political system was, under the rule of one man, a ‘complete democracy’.Footnote 19 And this notion left traces even later, as we shall see. Modern ideas, it may be noted parenthetically, can be equally paradoxical: Trajan’s rule was ‘not a monarchy’, a recent authority assures us.Footnote 20 Another Roman myth had it that Rome ruled the entire world: this idea was first articulated by Romans in the second century bc, and by the 70s bc was widely accepted, being reflected for instance in coin-types representing the globe [Figure. 1.3].Footnote 21 It appears commonly in Cicero.Footnote 22 It echoes on as late as the fifth century ad (Orosius, History against the Pagans 6.20.2). All the while the Roman elite, not to mention the Roman army, knew perfectly well on some level that they did not rule the whole earth or anything like it (though there is evidence that they underestimated the size of the territories that remained outside their power).

Figure 1.3. Denarius of the moneyer Cn. Lentulus (later consul), 76/5 bc. The globe on the reverse (b), together with the sceptre, wreath and rudder, indicates the Roman idea, much emphasized in these years, that Rome ruled the entire world. Crawford, RRC no. 393/1a

Presumably such myths – fantasies or delusions, if you will – were functional; they may indeed offer us important clues. Rome’s imaginary democracy reflected some continuing belief in the rights of the citizen. As for the notion of world-power, we shall want to ask when steely self-confidence turned into merely self-deluding arrogance.

Existing definitions of power, which are numerous, are somewhat unsatisfactory. One thing that is usually missing is the element of durability: the emperor or the paterfamilias may of course disappear from the face of the earth from one moment to the next, but in any given situation he is most unlikely to do so; power, in short, is more or less insistent. When Max Weber described power as ‘the probability that one actor within a social relationship will be in a position to carry out his own will despite resistance’ [my italics],Footnote 23 he seemed to imply that power had this characteristic of insistence, but his description was quite unusual in that respect.

Readers are entitled to ask which, if any, theory of power is most consonant with what this book has to say. My approach, as far as theory is concerned, is selective and highly critical. I simply seek throughout this study to discover how much the character of the Roman state’s constantly changing external relations was determined by its constantly changing internal power structures, and vice versa. This is how I want to consider the dynamics of imperial power and of its eventual demise. This is my principal objective.

To a quite startling degree modern studies of external and internal power in world history ignore each other. (Machiavelli, however, brought the two together in The Prince, chapters 19 and 21). Standard anthologies and general scholarly works tend to concern themselves either with ‘empire’ or with ‘power’, the latter being understood as a matter that concerns a given society’s internal relationships.Footnote 24 Even those analysts of political power who recognize that it also belongs to strong states at work beyond their own bordersFootnote 25 have little if anything useful to say about international power.

Theorists of empire have done rather better, and, since Stanislav Andreski and more recently Michael Mann, have made valiant efforts to relate imperial power to the internal dynamics of the imperial state. Keith Hopkins and I attempted more than thirty years ago to do just that, with regard to mid-republican Rome.Footnote 26 A brief but important paper by Tim Cornell applied a similar approach to the early Principate.Footnote 27 But the later you go in Roman history, the less of this work you find – the venerable example of Gibbon notwithstanding.Footnote 28 Neither Andreski nor Mann possessed expert knowledge about Roman history. International relations theorists, meanwhile, – always under the suspicion of being driven by presentist concernsFootnote 29 – have normally paid scant if any attention to the dictates of domestic politics.Footnote 30

Marxists of various stripes have notoriously paid ample attention to the nexus between economic and political formations and imperialism, and continue to do so down to this day.Footnote 31 But this work – so it seems to me – only illuminates the history of pre-modern states and empires in the most fitful way. As Moses Finley implied, the anti-Marxists are more dangerous than the Marxists,Footnote 32 but Marx’s ideas, even in their most sophisticated modern re-formulations, do not help one much to understand the relationship between the specific history of Roman imperial power and its internal power relations.Footnote 33 I shall certainly pay attention to the economic imperatives that conditioned Roman behaviour, but not because of any theoretical dogma.

This failure to connect has in fact a very long tradition behind it: some of the most brilliant older analysts of imperial power, Thucydides for instance, have partly failed to explain the internal power structures of the states they have written about, while some of the most brilliant analysts of intra-state power, Rousseau for instance, have been feeble commentators on external power.Footnote 34 The historian of the Roman Republic, however, is fortunate to have two sources, Polybius and Sallust, who for all their shortcomings (especially serious in the case of Sallust) succeeded in linking the patterns of Rome’s behaviour towards the outside world with its internal structures.

Various other thinkers about the workings of power, in particular Aristotle, Montesquieu, Marx, and Foucault, will be referred or alluded to in the pages that follow, but it will be obvious that the book as a whole is not Marxist, or Foucauldian, or within any other school.Footnote 35 Readers may infer from my recurrent stress on the interests of the large landowners that I want to understand the material basis of political power, but that does not mean that I consider this to be its only basis. Readers will also encounter the recurrent suggestion that Roman government was sometimes more oligarchical than it seems, but that does not make me a follower of Robert Michels (who invented the ‘iron law of oligarchy’). When Arendt asserts that ‘power is never the property of an individual’,Footnote 36 she is scarcely right; but when she continues that ‘it belongs to a group and remains in existence only as long as the group keeps together’, she enunciates a general truth; exceptions will always need to be justified.

What is wrong with what contemporary political science has to offer on the subject of Roman power is not so much its proneness to serious factual errors, though that will always jar with a historian, or to sheer fantasy (such as the notion that the late Roman Empire overtaxed its subjects).Footnote 37 The problem is rather that the explanations do not measure up to the phenomena. Take Peter Turchin, for instance, who knows more about the Romans than many. His conclusion is that:

two factors explain the rise of the Roman Empire: the high degree of the internal cohesiveness of the Roman people, or asabiya, which reached a peak c. 200 bc; and the remarkable openness to the incorporation of other peoples, often recent enemies.Footnote 38

That is all right, as far as it goes; the second of these factors is a commonplace of the historiography, and we shall have much to say about it. Rome’s ‘internal cohesiveness’ is more problematic. States that consistently win wars do indeed demonstrate this quality, and conversely we can certainly say that the diminished cohesiveness of the late Roman Empire was an important factor in its declining power, and that the main task of the historian of that phenomenon is to analyse why its cohesiveness decreased. But this is merely a necessary condition of empire-building. A lot more is needed, in particular an aggressive willingness to make war, a political elite with the capacity to organize and mobilize the state for war, and the ability to find the organizational techniques that are needed to retain and make use of what has been won.Footnote 39

Finally, people, collectivities, and states exercise power, so do abstractions and myths. So do images, as it first became fashionable to say about a generation ago. At its best, such work has raised vital questions about the ability of the powerful to control and influence diverse populations by means of architectural programmes, coin-types, public statuary and monuments, and more evanescent spectacles. Physical evidence of such kinds has already appeared several times in this short introduction. But there is still much work to be done on sociological and psychological as well as strictly archaeological aspects of this matter: to put it concisely, we know how the agents of Augustus shaped the Temple of Isis and Osiris at Dendur in upper Egypt, where he was depicted as a pharaoh (and we can remind ourselves by going to the Metropolitan Museum), but how the provincials who saw it reacted to it is, to say the least, uncertain. In recent times art-historians have begun to pay more attention to such questions.Footnote 40 A neglected key, in my view, is the elite audience. The Arch of Constantine, to take another example, no doubt evoked generalized awe in many of those who saw it, while its iconographic programme spoke only to a few – but those few were often men of influence.