Foreign Trade (Ea) gave to the Traders

I Introduction

The five other chapters in this part of Seals and Sealing in the Ancient World: New Approaches to Glyptic Studies address seals as an essential tool of urban life in late fourth through second millennia BCE Mesopotamia. The authors engage a variety of topics that are raised in glyptic studies within that context: the relationship between text and image at the origins of writing (Scott); the role of women in ancient administration (McCarthy) and in social and political life (Costello) as mirrored in the iconography of seals; the enduring importance of seals as objects of legitimization and authority (Smith); and the impact that changing political structures and administrative procedures had on the composition and iconography (Rakic). Each of these discussions draws on imagery, style, and materiality of seals and their ancient impressions.

What these and most seal studies share is an interest in the message carved in intaglio on the seal’s surface. This message invariably consists of recognizable images, symbols, abstract patterns, and/or inscriptions. One of the most intriguing problems raised by seal imagery is its “meaning” and its association with the owner or individual who either displays the seal or uses its impression to participate in acts of administrative or juridical communication. After fifty years of scholarship focusing squarely on this problem, what is clear is that there are no hard-and-fast rules which determine that relationship. Only rarely can meaning actually be grasped; more often only the domain of meaning can be approached. Perhaps the clearest relationship between image and administrative meaning is that carried on a subset of official seals issued by the Neo-Sumerian rulers to their officials (Winter Reference Winter, Gibson and Biggs1987). A similar relationship can be convincingly asserted for official seals of the Old Akkadian court of Naram-Sin (Zettler Reference Zettler, Gibson and Biggs1977, Reference Zettler and Crawford2007; Rakic Reference Rakic2003 and this volume).

One topic that is not explicitly raised in any of the chapters in this section is a discussion of the administrative role of seals. Thus, as an introductory contribution, I will first offer some summary remarks on the role of seals followed by a brief case study of a novel setting in which seals seemed to have been used on the Iranian Plateau during the third millennium BCE. This is not a comprehensive treatment of the subject since there is a very broad range of purposes that seals performed. Rather, I wish to bring this dimension of seal use into the range of approaches considered here as it applies to the Late Chalcolithic and Early Bronze Age (ca. 3500–1800 BCE).

II Administrative Role of Seals in Mesopotamia

In order to contextualize this case study of a fascinating body of glyptic art that has been recently added to the corpus of ancient Near Eastern seals from Bronze Age Iran, it is useful to present an overview of how seals were used in administrative contexts from the earliest prehistoric times into the third-millennium Bronze Age. It is significant that seals, that is to say stones and other durable materials engraved with imagery meant to be impressed on malleable materials, appear very early in village contexts.

As has been repeatedly observed, seals were meaningful and powerfully symbolic objects in their own right in Mesopotamian society serving as amulets and markers of status, office, identity. They were associated across the entire spectrum of society from everyday citizens to the royal court and temple personnel. Even gods had their seals. We are told in the omen texts (perhaps ironically) that they were even used as weapons, responsible for the deaths of either the Old Akkadian king Rimush or Sharkalisharri (Goetze Reference Goetze1947). Their materials had specific significance as well, derived from their color or exotic origin. As objects they stood in for and were extensions of their owners (Collon Reference Collon1987). Beyond their importance and meaning as objects, an equally important function was embedded in their ability to make an infinite number of identical marks that carried significance as a trace of the seal itself. The ancient fragments of clay found in archaeological contexts remain to us as the residue of administrative activity in the form of seal impressions which preserve in the positive a rendering of the negative design carried on the original seal. I am concerned here primarily with the impressions on mud masses and the variety of domains in which they functioned.

From their very invention in the aceramic Neolithic period (Duistermaat Reference Duistermaat and Akkermans1996) the ability of stamp seals to make endlessly reproducible and identical marks was exploited. Egalitarian communities of the Late Neolithic phases used seals to control goods for the larger group, making sure that communally held goods were protected from unauthorized distribution. During the subsequent Ubaid period, the household replaced the community as the primary economic unit within settlements. This reorganization led to the unequal distribution of resources, with some families having greater access to wealth and resources than others. The earliest evidence for this new organization is reflected in a new tripartite house plan that is found first in southern Mesopotamia. During the long Ubaid period this house plan, used by scholars as proxy for this new economic structure, spread to the north, where stamp seals had long been part of the egalitarian organization of storage and distribution. Under the new regime stamp seals were used within each household economic unit to control both mobile and stationary storage (Rothman Reference Rothman and Ferioli1994a), probably within the extended family. It is with the Uruk period in the fourth millennium that seals found their full administrative potential. This is the moment when cylinder seals replaced stamps as the dominant glyptic form. In the increasingly complex economic and social organizations, the imagery carried on seals, as Scott develops in her chapter, exploded. Although the precise domains of their meaning are still debated, it is obvious that the imagery on Uruk seals transmitted messages that referred to institutions and various production sectors of the economy (Brandes Reference Brandes1979; Nissen Reference Nissen, Gibson and Biggs1977, Reference Nissen, Finkbeiner and Rollig1986; Dittmann Reference Dittmann, Finkbeiner and Rollig1986; Pittman Reference Pittman1994a, Reference Pittman, Ferioli, Fiandra, Fissore and Frangipane1994b, Reference Pittman and Petrie2013b). They were deployed within an administration meant to impose control within the production and the distribution of surplus that was accumulated for the benefit of the gods and goddesses of the cities and the emerging elite who represented them. It is in that intense symbolic cauldron that writing was invented shortly after the introduction of the cylinder seal. The ingenious symbolic technology which had the potential to capture spoken utterance in conventional marks undoubtedly facilitated the appearance of true cities and urban life which characterize Mesopotamian culture. It is obvious that some of the earliest signs in this system of symbols that lead to writing were drawn directly from images carried on the cylinder seals. The close cognitive relationship between seals and writing was established at this point and an inexorable process was begun which linked changes in the writing system to changes in the imagery and the administrative functions of seals (Pittman Reference Pittman, Ferioli, Fiandra, Fissore and Frangipane1994b; see Scott, this volume).

When seals are considered as administrative tools, one important category of information about function is essentially independent of the seals themselves, but is rather carried on the mud matrix of their impressions. More than fifty years ago, Enrica Fiandra and Piera Ferioli revolutionized seal studies by grasping the obvious but previously unappreciated fact that the mud masses carrying impressions of seals were an additional source of information about ancient economies and administrations. Through experimentation and careful observation, first on impressions from the Aegean and Shahr-i Sokhta and then on the huge and precisely excavated caches of sealings from Arslantepe, they were able to identify with precision the types of objects that were impressed by seals (Fiandra Reference Fiandra1975; Ferioli and Fiandra Reference Ferioli, Fiandra, Gnoli and Rossi1979; Ferioli et al. Reference Ferioli, Fiandra, Frangipane, Frangipane, Ferioli, Fiandra, Laurito and Pittman2007). Using the Semenovian method (Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Korobkova, Longo, Plisson, Skakun, Longo and Skakun2005), they identified a series of door sealings and differentiated them from various types of containers, including jars, jar stoppers, leather and cloth bags, baskets, and the like. Introducing this analytical control over the morphology of sealings has allowed us to differentiate between stationary storage, that is, storerooms that would be opened and closed under the supervision of an authorized individual or group, and individual containers that would be opened upon receipt, or when their contents were either dispersed or replenished. Having established this systematized and tested typology of features for each functional type, publication of seal impressions now typically includes a drawing and an identification of the object impressed by a particular seal.

A Administrative Functions in the Uruk Period

While there are a number of collections of seal impressions whose functions have been studied, those found at Arslantepe in eastern Anatolia have received the most thorough examination (Frangipane et al. Reference Frangipane, Ferioli, Fiandra, Laurito and Pittman2007). During the late fourth millennium the site of Arslantepe was the home of a small polity which made extensive use of seals to administer the internal receipt and distribution of foodstuffs. The evidence was found in storerooms and distribution areas within a building that has been identified as a “palace.” The importance of the building is made obvious through the presence of wall paintings marking the most significant spaces in the structure. One of the most obvious features of the Arslantepe corpus of seals is the fundamental coherence of the imagery and style of the seals (Pittman Reference Pittman, Frangipane, Ferioli, Fiandra, Laurito and Pittman2007). The majority of the more than three hundred seals are stamps. There are fewer than ten cylinder seals, and all but three are carved with imagery and in a manner that connects them closely with the stamp seals. Neutron activation analysis confirmed the analysis of the functions. Both lines of inquiry concluded that the sealings were used in an internal system of administration controlling the distribution of food for consumption by local groups, probably in the form of communal feasting in recognition of work undertaken for the benefit of the “palace.” All of the participants belonged to a single administrative community and they were all operating by essentially the same rules. This feature is closely comparable to that developed by both Regulski and Nolan within the Early Dynastic and Old Kingdom administrative systems that they present in this volume. Indeed, describing the rules for each administrative system is a large part of the systematic analysis of the role of glyptic in systems of administration.

An essentially contemporary collection of sealings was found at the site of Hacınebi on the bend of the Euphrates. At that site, two seal-using communities have been identified on the basis of the morphology, style, iconography, and function of the seals (Pittman Reference Pittman1999). One was “local,” using traditional Late Chalcolithic stamp seals having distinctive designs and closing smaller mobile containers. The other had close formal ties to southern Late Uruk communities, apparently based at Susa. The seals were uniformly cylinders, the imagery was closely comparable to contemporary seals from Susa, and they served to seal hollow clay balls, jar stoppers, tablets, and larger storage jars, functions not preserved in the local sealings. What is clear from this evidence is that each community followed the functional rules consistent with their system. There was very little mixing of the two communities, and there was no evidence that they were interacting administratively at the site. Each had its own administrative domain. Additionally there was very little evidence for what could be construed as “trade” between the colony at Hacınebi and either the south or the neighboring hinterland. Neutron activation analysis did identify several sealings as coming from Khuzistan, the region in which Susa is sited (Blackman Reference Blackman1999). It is most likely that these items did not arrive as objects of “trade” but rather as provisions, or care packages of special items brought by countrymen to their fellows in the wilderness. Although Hacınebi and other Uruk-period sites have been identified as “colonies” or outposts of communities from the southern alluvium, no one has argued that the residue of administrative materials is in itself evidence for trading or mercantile activity (Algaze Reference Algaze2004). Rather, similar to what was observed at Arslantepe, the administrative evidence in the “colonies” is understood as remains of local populations or southern inhabitants present in the region each using seals following administrative protocols consistent with their individual communities in order to manage local concerns.

B Administrative Role of Seals in Third-Millennium Mesopotamia

Several large groups of seal impressions, dating from the third millennium, have been recovered at various Mesopotamian sites that have been subjected to an iconographic and stylistic analysis in an effort to determine the roles of various types of seals within administrative systems. Among others, they include Jemdet Nasr (Moorey Reference Moorey1978; Matthews Reference Matthews1993), Seal Impressions Strata at Ur (Zettler Reference Zettler, Leonard and Williams1989; Moorey Reference Moorey1979; Matthews Reference Matthews1993; Scott Reference Scott2005), the Ash Tip at Abu Salabikh (Green Reference Green1993), Fara (Martin Reference Martin1988), and in Syria at Tell Beydar (Bretschneider and Joachim Reference Bretschneider and Joachim2011). Although obviously different from the assemblages discussed above, all of these have also been interpreted as the residue of internal administration concerned with the collection, storage, redistribution, and dispersal of commodities or labor within an urban community either between or within institutions or from institutions to individual laborers or teams of laborers in the form of rationed necessities. Indeed, as the chapters by Rakic, Regulski, and S. T. Smith in this volume show, this is the most common administrative context in which seal impressions are used. This has important implications for the ways in which imagery of seals used in such contexts signals difference.

In addition to controlling commodities for distribution, the other important function of seals was to impress tablets or other documents. Like impressions on closing and locking devices, impressions on documents began even before writing was invented. In the Middle Uruk period the hollow clay balls containing counters and tokens were usually impressed on their surface with as many as three cylinder seals as well as a stamp seal. Although we have not cracked the code of meaning for these combinations of impressions, in the anepigraphic environment, it is clear that the seal imagery served to convey complex messages that referred to the subject or object being controlled (textile production, food distribution) as well as the identity of the controlling authority. Although a few Uruk IV and even fewer Uruk III/Jemdet Nasr tablets are seal impressed, with the appearance of the next stage of writing, as represented by the Archaic Texts found in the Seal Impression Strata at Ur, seals were no longer used to impress tablets. This separation of written documents and seal impressions was maintained throughout the Early Dynastic and Old Akkadian periods when only a very few tablets were seal impressed. Beginning with the Ur III period, however, tablets were again uniformly impressed with seals, this time having the very clear function to identify, through the cuneiform inscription as well as through imagery, the identity of the witness to the transaction recorded in the tablet. Because the iconography of the seals used to impress the tablets is so consistent (one of several versions of the presentation scenes), the seals of the Ur III period can effectively only be differentiated through their inscriptions. In the following Old Babylonian and Kassite periods, seals were frequently impressed on tablets, particularly those of a juridical or contractual nature.

What I want to emphasize through this review of the administrative functions of seals in Mesopotamia is that seal imagery was meant to be understood within particular administrative contexts. It was not meant to flag identity to different external groups, but rather the variety within the imagery was internal to the particular administrative process. Understanding this allows us in each case to treat the residue as the product of the administration of an essentially internal process of the control within a closed system of accounting and distribution. When applied to tablets in the Ur III period, the function of the impression was to convey official sanction of the transaction or to identify the parties legally responsible for the accuracy of the record (Steinkeller Reference Steinkeller, Gibson and Biggs1977; Zettler Reference Zettler1987; Winter Reference Winter, Gibson and Biggs1987). The variety within such groups of sealings tends to be low. While there might be many individual seals, they can be differentiated first through their inscriptions and then through iconography but rarely through style. If there are several styles with variation within them, each tends to be represented by many examples.

These general parameters can, I believe, be clearly seen in practice within the body of seals found impressed on mud masses in level 8–4 of the Seal Impression Strata (SIS) (Legrain Reference Legrain1936; Scott Reference Scott2005). Although there is considerable internal iconographic variation, there are really only three categories of seal images carried on those seals: abstract designs (the smallest number), figural seals showing animals and humans, and the so-called City Seals. Although these were all found mixed together in the trash, it is likely that they originated from individual institutions, perhaps at different times, each of which had its own imagery. There is on occasion a mixing of these three categories, which reinforces the idea that the imagery that each institution was using was comprehensible to the others. These seals were used among administrators following the same conventions of meaning for the iconography. That is to say they used the same “visual language” and probably also the same natural language. They were all residents of Ur, probably speaking Sumerian, and engaging in the administrative protocols of their various institutions. All were used in the task of controlling the movement of special goods within the same system to which they belonged. Within the SIS corpus one outlier serves to prove the rule. Several impressions of the same seal showing a scene of animals acting as humans can clearly be identified as coming from the outside (Legrain Reference Legrain1936: pl. 20 no. 384). Through comparisons with seals and sealings from Susa, it is immediately obvious that this is the single clearly recognizable proto-Elamite sealing among the hundreds of local examples. I am inclined to interpret this one exemplar not as evidence of trade between Ur and Susa, but rather as evidence of an official from neighboring Susa present, and apparently active, at Ur in some unknown but probably special capacity. While the City Seals are understood to be administering the collection and the distribution of specialty goods to the temple of the goddess Inanna, the imagery is not meant to differentiate one city from the other. Rather, they are meant to show that the individual cities were unified in this redistribution activity (Matthews Reference Matthews1993; Steinkeller Reference Steinkeller and Abusch2002).

C Function of Seal Imagery in the Old Assyrian Trading Colonies

Outside Mesopotamia proper, in Anatolia, an extremely interesting corpus of seal impressions is preserved in association with the thousands of tablets and envelopes found in archives of the Old Assyrian karum at Kültepe/Kanesh in central Anatolia. The contents of many of the tablets have been studied over generations to produce a fascinating record of a colonial installation of traders in the nineteenth century BCE. The ethnic diversity of the community of traders can be identified by their names, and is made up of individuals from the city of Ashur, together with others from Anatolia. A small minority of the seals carry inscriptions. They have been formally categorized into four distinct style groups based on both iconography and style of cutting. These have been given regional names, including the Old Assyrian style and the Anatolian style. Several studies have tried to penetrate the patterns of use by correlating seal type and iconography with the user as identified in cuneiform written on the document itself and not on the seal (most recently Lassen Reference Lassen2012; Larsen and Lassen Reference Larsen, Lassen, Kozuh, Henkelman, Jones and Woods2013). What appears is a highly complex pattern that seems to evolve over time. While there is clearly some preference based on ethnic identity, by the third generation of seal users the mixing of populations is reflected in the individual choice of hybrid iconography. In the early years of the commercial arrangement apparently the seal groups correlate rather closely with the user’s ethnic origin, but by the time of the second- and third-generation traders, users apparently felt free to choose seals that crossed over “ethnic” categories as they have been identified by modern scholars. However, there is a local Anatolian style that is consistently and only used by indigenous Anatolians who do not directly participate in mercantile activities but are rather involved in peripheral issues. Whatever the relationship that existed between the seal and the user, the function of the seal was in all cases a legal one, witnessing the accuracy of the content of the document. It is never used to secure or lock containers or to control the opening and closing of storerooms.

Cylinder seals were introduced into central Anatolia by the traders who arrived from Assyria and administered their commercial activities using the symbolic technologies of cuneiform writing and seals to record and ratify transactions. Because of the multi-ethnic context of the commercial arena, an important element in the seal imagery was developed to differentiate ethnic affiliation. Although the recent analyses of the seals and ethnic identity of their owners show that this was a complicated and evolving relationship, a fundamental correlation has been established as an important motivating element in the selection of certain seal styles by individual users.

III Administrative Function of Seal Imagery on the Iranian Plateau: Merchants and Traders

With this background, which draws on previous scholarship, I will introduce another case study concerning the administrative function of seals. It is one that does not concern the administration of an internal organization but rather it is one dedicated to controlling the acquisition and distribution of raw materials between and among individuals of distinct ethnic identities. While also related to trade among and between distinct ethnic communities, this case is different from the Old Assyrian example in a number of aspects. Most importantly, it exists entirely outside the domain of writing. As such, there is more pressure on seal imagery to carry the message of identity. In both cases seals were used only within the commercial context and were not, as typical of Mesopotamia proper, used to administer internal distribution of goods or services. The primary audience for the seal imagery in each setting was other participants in the trading community.

The evidence I consider here comes from recent excavations on the Iranian Plateau at the site of Konar Sandal South (hereafter KSS). During the third millennium KSS was large entrepôt or nexus located at the crossing of routes that linked the greater Iranian Plateau to both the east and the west. As such it attracted traders from both nearby and far away. To judge from the glyptic evidence, the site (and probably others like it) filled this role for about 500 years until the relationship between the west and the highland became militarized and commercial actors were replaced by agents of the state, first soldiers and armies and later diplomats and official delegations. What leads to this conclusion is the analysis of internal variability of the seal imagery and style and their administrative functions as determined through the morphology of the sealings.

Konar Sandal South is the largest of three large mounded sites located in the northern part of the Halil River Valley in south central Iran in the province of Kerman. They are about 30 kilometers south of the modern city of Jiroft, which now serves a similar purpose as the city through which exports from Iran are transported and conversely which receives goods imported into Iran from the great ports at the Straits of Hormuz. First identified by Sir Aurel Stein (Reference Stein1937), KSS and the Bronze Age occupation of the Halil River Valley remained essentially invisible to the archaeological community until vast looting of thousands of graves occurred following a massive flood in 2000 (Madjidzadeh Reference Madjidzadeh2003a, Reference Madjidzadeh2003b). Among the artifacts confiscated and deposited in local museums were hundreds of carved chlorite objects of a type well known from the earlier excavations of Tepe Yahya (Potts Reference Potts2001). After the looting was stopped, Yousef Madjidzadeh led six seasons of excavation at KSS, Konar Sandal North, and Qaleh Kuckeck (Madjidzadeh Reference Madjidzadeh2003b; Madjidzadeh and Pittman Reference Madjidzadeh and Pittman2008). This related complex of mounds was the center of dense occupation in the remarkable fertile valley of the Halil River during the Early Bronze Age.

Of the fourteen trenches that explored KSS, three produced seal impressions. While a complete functional analysis has yet to be completed, most are sealings from small containers, bags, baskets, jars, and boxes. What distinguishes them most remarkably is the variety of styles, iconography, as well as the types and shapes of the seals. This variety stands in direct contrast to the homogeneity of the glyptic used within internal administrative systems in Mesopotamia. Indeed, it is considerably greater than that of the Old Assyrian colony period. There can be little doubt that this is the residue of activity of individuals engaged in the acquisition and distribution of precious raw materials that were consumed by elites both locally and abroad (Pittman Reference Pittman, Madjidzadeh and Pittman2008, Reference Pittman, Fahimi and Mashkour2012, Reference Pittman and Potts2013a, Reference Pittman and Petrie2013b). Unlike the Assyrian colony situation in which the seals are applied to documents that record the trading activity, what we see at KSS is the residue of the actual trading activity in which seals were used by the individuals as tools of the profession. The sealings are not meant to be records, for there is no evidence of archiving. Rather, they served as a direct controlling mechanism among the participants of exchange.

From the evidence that we have so far from KSS, this activity began in the early centuries of the third millennium at a time equivalent to the Seal Impression Strata of Ur (ED I) and continued until the end of the Early Dynastic period or even into the earliest years of the reign of Sargon (Pittman Reference Pittman, Fahimi and Mashkour2012). It seems to have been most intense during the period of the Royal Cemetery when Ur was a dominant city in southern Mesopotamia. There is no evidence at KSS for the presence of seals or administration during the classical Akkadian or Ur III periods. However, the site itself continued to be occupied, and it is during that period that the fortified Citadel was built (Madjidzadeh and Pittman Reference Madjidzadeh and Pittman2008). The end of the residue of sealing from mercantile activity at the site coincides with the fundamental change in the way in which Mesopotamia engaged with the Iranian Plateau. By the reigns of the Old Akkadian kings Rimush and Manishtushu the relationship between Mesopotamia and Iran had become militarized. The trade relations that remained were mediated by maritime merchants from the Indus Valley, Magan, and later Dilmun who operated in the Gulf as middlemen for preciosities from the plateau, Central Asia, the Indus Valley, and vast quantities of copper from Oman (Potts Reference Potts1999; Ratnagar Reference Ratnagar2004).

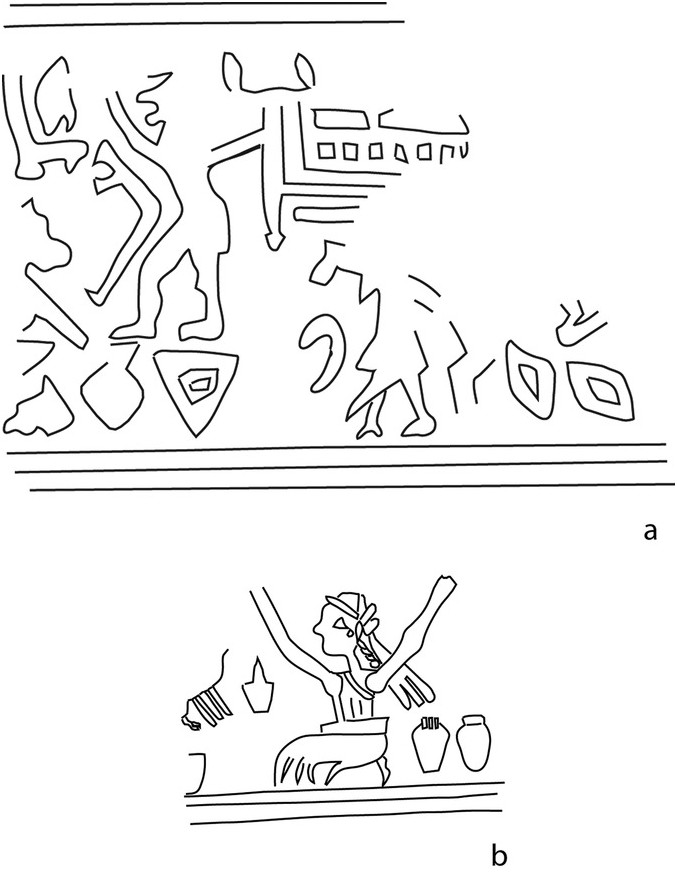

A Early Third Millennium: Trench XIV

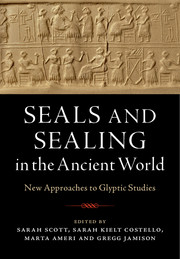

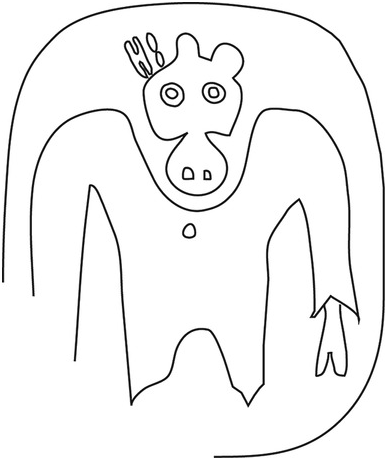

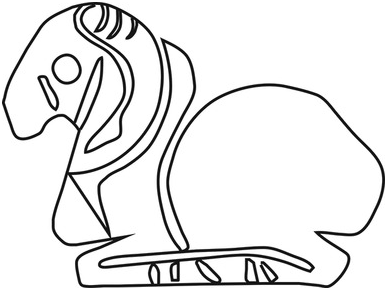

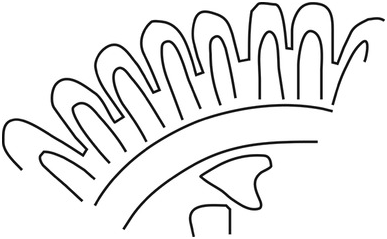

Trench XIV provides the earliest evidence for the presence of traders on the Iranian Plateau and at the site. Four seal impressions were found together in burnt trash within the walls of a structure. Although the context is tertiary, their importance cannot be overestimated. As discussed at length elsewhere (Pittman Reference Pittman, Fahimi and Mashkour2012), the most significant is the impression of a City Seal of a type that must have originated at Ur (Fig. 2.1). The fact that this image was carried on a door sealing makes it certain, in my mind, that a trader from Ur who was provisioning the Ki-en-gi league was present at KSS around 2900 BCE. The implications of the presence of this type of seal on the Iranian Plateau are considerable for our understanding of the system that the City Seal style represents (Matthews Reference Matthews1993; Steinkeller Reference Steinkeller and Abusch2002). We must however, await further excavation with more extensive finds of administrative materials before these can be properly developed. What is important for this discussion is that the City Seal was found together with three other impressions of stamp seals, each different and each belonging to a distinct glyptic tradition. One is the impression on a rectangular seal with curved corners of an image of a standing bovid with a distinctly humanoid aspect (Fig. 2.2). Although there is nothing with which this image can be closely compared, it is obviously related to the contemporary proto-Elamite image of the powerful standing bovid that is frequently paired with an equally powerful feline (e.g. Amiet Reference Amiet1972: no. 1013). Although at this point purely speculative, this stamp could be the seal of a proto-Elamite participant in this commercial activity (Damerow and Englund Reference Damerow and Englund1989). The two other stamps add to the diversity. One is in fact not a seal, but rather the impression in a large mud mass of uncertain function of an amulet in the shape of a recumbent bovid (Fig. 2.3). A number of similar amulets were found among the looted materials now in the museum in Kerman (Madjidzadeh Reference Madjidzadeh2003a: 167). The type is also known in substantial numbers from both northern and southern Mesopotamia and at Susa during the Uruk and Jemdet Nasr periods. Finally, the last stamp-seal impression in this early context (Fig. 2.4) finds its best parallel among the stone stamp seals known from Shahr-i Sokhta Phase II (Tosi Reference Tosi1983: fig. 73 middle row right). Even with this minimal evidence, we can conclude that as early as the ED I period, KSS was a place where individuals were coming from the west (Ur), certainly by the maritime route, disembarking in the region of modern-day Bandar Abbas or Minab, and making the easy five-day journey overland to the northern reaches of the Halil River Valley. KSS was located on the overland routes from the north and northeast and it is in a valley that is surrounded by mountains full of timber, metal, and soft and hard stones. There these Mesopotamians met people from the region and from the east, perhaps from the Helmand River Valley who had arrived along the easy overland route following the Bampur River. Although not from Trench XIV, a nearby Trench XI produced a radiocarbon sample of 2880–2690 BCE 2 sigma which is precisely the conventional date assigned to the City Seal impressions from Ur (Madjidzadeh and Pittman Reference Madjidzadeh and Pittman2008).

2.1. Drawing of fragmentary cylinder-seal impression. City Seal comparable to those found in Seal Impression Strata from Ur. Konar Sandal South, Trench XIV: 2008XIV002. Preserved height 3.4 cm.

2.2. Drawing of impression of stamp seal showing frontal standing bull. Konar Sandal South, Trench XIV: 2008XIV003. Preserved height 6 cm.

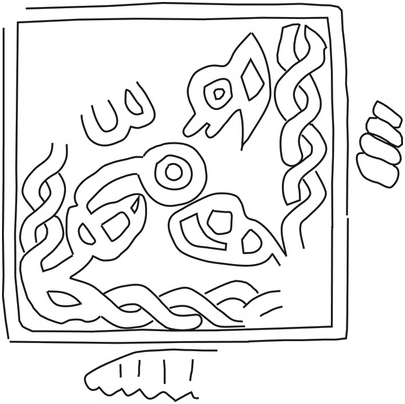

2.3. Drawing of impression of stamp amulet in the form of a recumbent ram. Konar Sandal South, Trench XIV: 2008XIV004. Preserved height 2.4 cm.

2.4. Drawing of stamp-seal impression with a circular petal pattern. Konar Sandal South, Trench XIV: 2008XIV001. Preserved height 3 cm.

B Trenches III and V

The next phase of this interaction is preserved in two distinct contexts, Trench III and Trench V (Madjidzadeh and Pittman Reference Madjidzadeh and Pittman2008). Taken together, these two groups of seal impressions, like the much smaller set in Trench XIV, preserve a remarkable variety of styles and iconography. The lowest excavated level of Trench III extends under the high Citadel mound. In the level that extends under the Citadel, an architectural complex of several rooms was revealed. It was enclosed by a wall some 10 meters wide that apparently encircled a large portion of the lower town. In the latest of two phases of this complex were found almost one hundred seal impressions on the floors of several adjoining rooms (Pittman Reference Pittman, Madjidzadeh and Pittman2008). Together on the same floor was a burned branch of a Sandal tree that produced two c14 dates having the range 2480–2280 BCE 2 sigma. Also found on the floors were a number of intact ceramic jars, and a broken fragment of a chlorite plaque in the shape of a scorpion man with raised arms very similar to those confiscated from the looters (Madjidzadeh and Pittman Reference Madjidzadeh and Pittman2008).

The presence of seal impressions supports the identification of the building, at least in its last phase, as an administrative quarter. As I have argued elsewhere, some of the seal impressions in Trench III show strong connections to Mesopotamia, but none were certainly made with seals manufactured in Mesopotamia (Pittman Reference Pittman, Fahimi and Mashkour2012). Additionally there are many other seals, both stamps and cylinders that belong to distinct Iranian traditions. While we do not yet have enough comparative evidence to precisely locate the regions from which those seals derived, it is clear that a number of distinct style communities are represented.

The other deposit that produced many seal impressions is a trash pit on the side of a large open-air working platform which was revealed in the excavations of Trench V. Although it is a secondary rather than primary context, the contents of this pit are uniform, consisting of trash generated in the course of the lapidary craft industries undertaken on the platform. Among the impressions are several examples of a stamp seal that was also present in Trench III (Fig. 2.5). This means that while the two deposits might represent a number of decades, for this discussion they can be treated as essentially contemporary. They are two different contexts in which administrative activity took place. Trench III is an administrative setting at a remove from the craft production area while Trench V is directly associated with the platform on which craft production of semi-precious stones took place.

2.5. Composite drawing of square stamp seal in linear style showing heads of snakes on twisted necks coming together in the center. Examples of this stamp seal were found in both Trench III and Trench V. Konar Sandal South, 2005III114, 2005III119, 2005V004, 2005V003. Preserved height 2.5 cm.

C Distinct Sealing Communities

What follows is a brief presentation of the distinct sealing communities that can be identified through the style, iconography, and morphology of seal. While it will never be possible to associate “ethnic” labels with the various Iranian groups, further exploration will surely reveal the home region of some. That seal types can be associated with distinct communities during the Bronze Age has been convincingly demonstrated for the Indus Valley merchants (Possehl Reference Possehl, Weber and Belcher2003), for the Indus-related traders (Vidale Reference Vidale, Franke-Vogt and Weisshaar2005; Laursen Reference 425Laursen2010b), and later for the Dilmun traders (Crawford Reference Crawford2001). What is significant about the glyptic material from KSS is that it is the only place where the actual residue of the actors engaged together in the business of trade and exchange has been found. At all of the other sites, seals rather than sealings are found. Further, among those actors is positive evidence for the presence of Mesopotamians on the Iranian Plateau also engaging in the acquisition of the preciosities that supported the emergent elite of the Early Dynastic city-states.

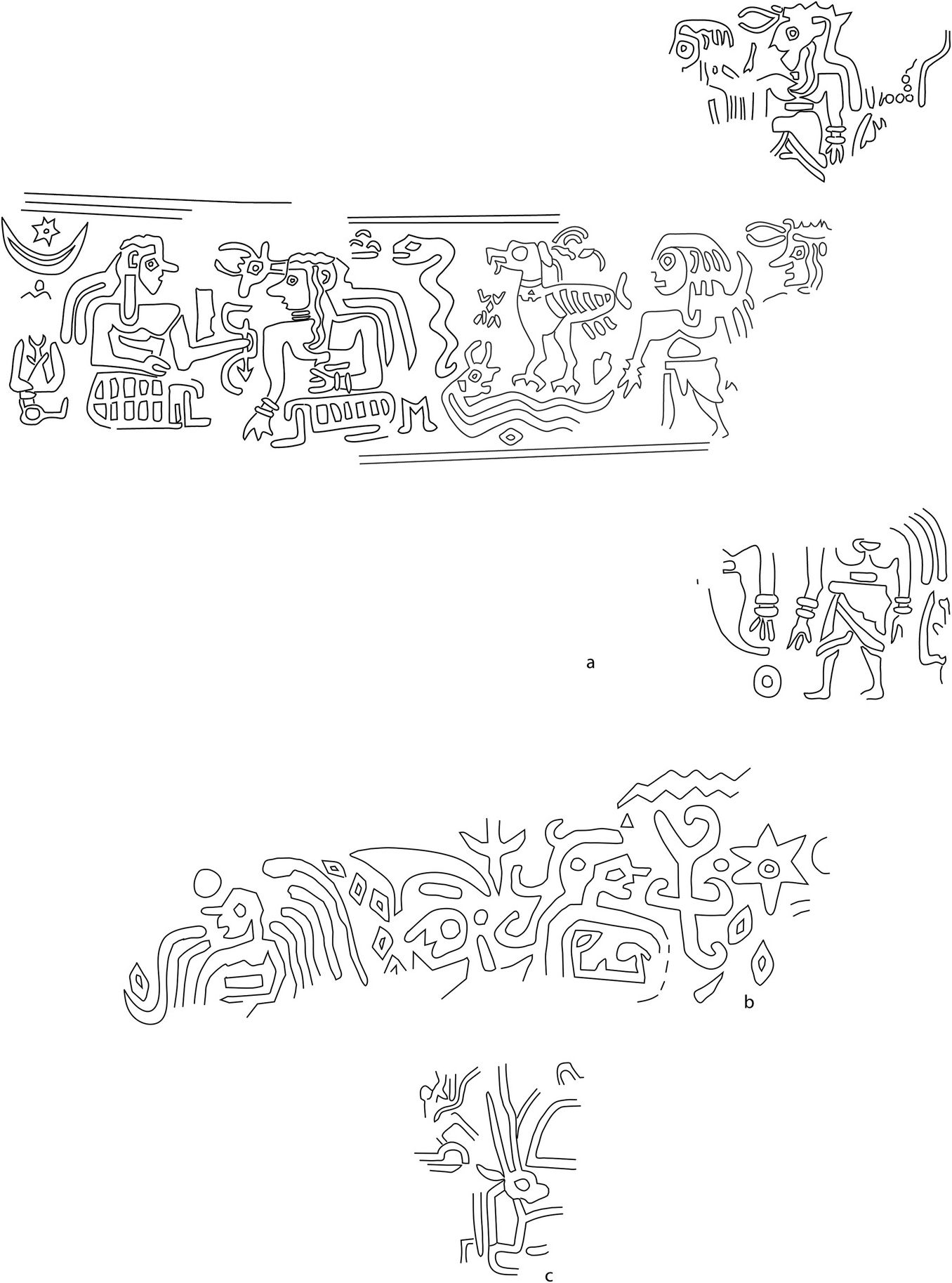

1. Mesopotamian Community (Trenches III and V)

Unlike in Trench XIV, no seal impression found on the floor of the administrative rooms in Trench III can positively be attributed to a seal made in Mesopotamia. However, the iconography of several impressions exhibits close association with Mesopotamian imagery and style. They include one fragment of a combat scene (Fig. 2.6a); another carries a scene showing calves emerging from either side of an animal bier topped with divine signs (Fig. 2.6b). In Trench V, however, almost a dozen fragmentary impressions (Fig. 2.7) can be identified as having been made by cylinder seals made in Mesopotamia. Indeed, they find their closest comparisons at Ur among the combat scenes preserved in the Royal Cemetery (Boehmer Reference Boehmer1969). Not discussed here, but certainly important, is a group of seals whose imagery is a combination of Mesopotamian and Iranian features (Pittman Reference Pittman, Lamberg-Karlovsky and Cerasetti2014b).

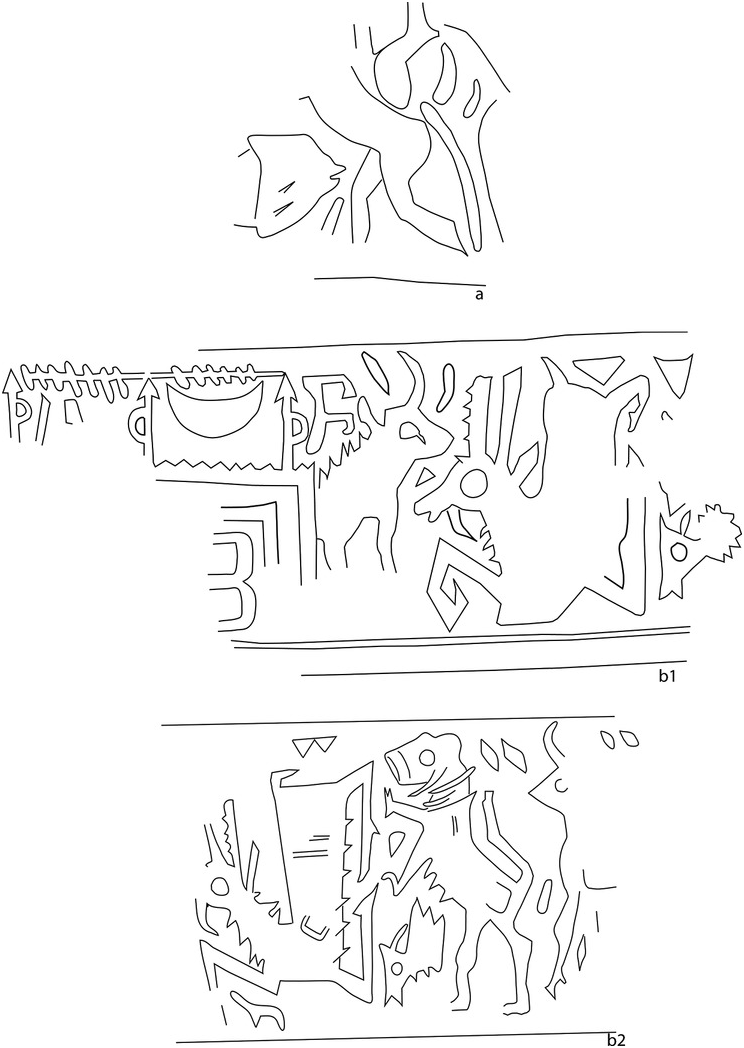

2.6. (a) Drawing of fragmentary cylinder-seal impression. Animal combat design in the style of Mesopotamian Early Dynastic combat scenes. Konar Sandal South, Trench III: 156III306. Preserved height 3.3 cm. Drawing by author; (b) Drawing of two fragments of cylinder-seal impressions. Bulls emerge from either side of an animal bier having emblematic standards on the roof; to the side is a lion dominating a caprid. Konar Sandal South, Trench III. Fragment 1: 130III306, preserved height 3.8 cm; Fragment 2. 154III306, preserved height 3.8 cm.

2.7. Drawing of fragmentary cylinder-seal impression. Combat scene made by a cylinder seal of Mesopotamian manufacture. Konar Sandal South, Trench V: 2005V098. Preserved height 2.25 cm.

The remainder of the seals represented among the administrative residue can be broadly classified as belonging to Iranian traditions. Among them I recognize six groups, some of which have overlapping features. Some groups find close comparisons at Susa, others find close comparisons at Tepe Yahya and Shahdad, and a group of stamp seals finds comparisons on the Iranian Plateau at sites to the east including Damin and Shahr-i Sokhta. Three groups of seals find comparisons only among the glyptic art from KSS. Although much more work needs to be done in the region before styles can be associated with locations, these types must represent an activity community of local traders and administrators involved in the commerce.

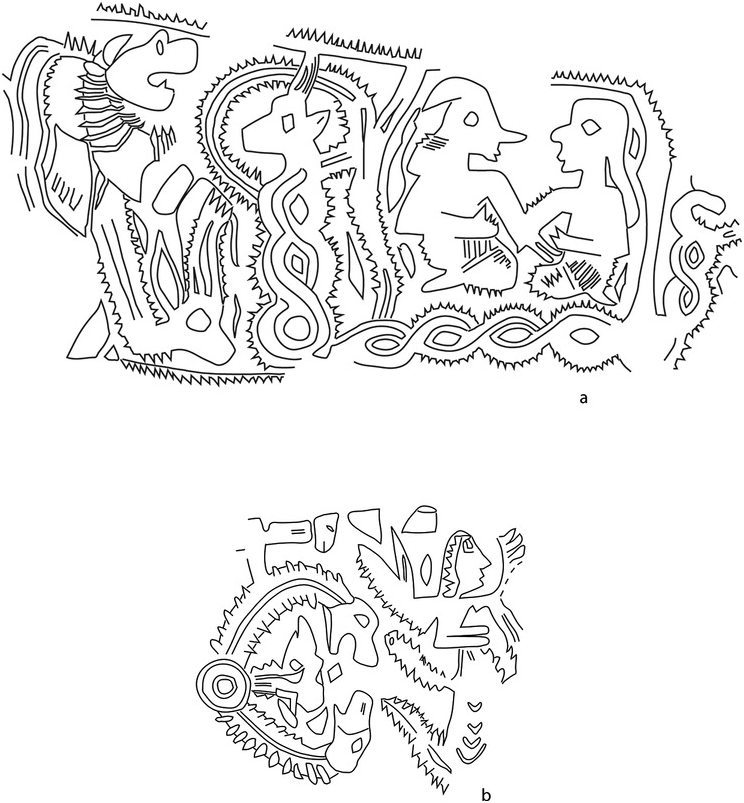

2. Iranian Community 1: Hatched-Border Seals (Trench V)

The Hatched-Border Group is found in both Trench III and V and, as its name suggests, it is defined by the use of fine saw-toothed hatching on the borders that define the upper and lower zone of the image field. There are twenty-one fragments that carry this type of design (Fig. 2.8 a, b; Fig. 2.11a). Some feature small figures, both animals and humans which in some cases find distant similarity to Early Dynastic prototypes. At Susa this group is also represented by a dozen examples published by Amiet (Reference Amiet1972: 1404, 1407). The imagery of the Susa examples also carries animal combat scenes and heroes fighting animals. It is important to note that there are no examples of this style at sites in Mesopotamia, with the notable exception of a single cylinder seal, found at Ur (Legrain Reference Legrain1951: no. 632). This seal is often associated with the Indus Valley because of the humped bull (Aruz Reference Aruz, Aruz and Wallenfells2003a). However, in the context of the seals from KSS, it seems obvious that it belongs to the hatched group discussed here. The question remains if seals of this type were produced in Susa as well as in the Halil River Valley. What is relevant for this discussion, however, is that the hatched-border seals can be associated with a group of traders, perhaps coming from Susa, perhaps originating in the Halil River Valley, who engaged in the trafficking of commodities secured through negotiations at KSS.

2.8. (a) Drawing of a fragmentary cylinder-seal impression. To the left confronting heroes, in the center an animal combat, to the right a hero fighting a quadruped above the head of a cervid, top border hatched. Konar Sandal South, Trench V: 044V402. Drawing by author; (b) Drawing of a fragmentary cylinder-seal impression. Head of a larger cervid; squatting female figure between its horns. To the right is a human figure with arms raised above a second human figure also with arms raised who appears to be falling. To the far right are the three curls of the head of what was probably a large female figure facing right, top border hatched. Konar Sandal South, Trench V: 154V402. Preserved height 1.1 cm.

3. Iranian Community 2: Pantheon Group (Trench V)

The third group of seals which shows connections to the outside must certainly be identified as originating in the region of Kerman province. This group is defined by a specific iconography that is rendered in two different styles. The imagery consists of anthropomorphic deities distinguished by wings, horned headdresses, or vegetation emerging from their bodies. Seals (not sealings) having this imagery have been found at Yahya IVB (Pittman Reference Pittman, Lamberg-Karlovsky and Potts2001a: figs. 10.46, 47, 48, 49, 51) as well as in graves at Shahdad (Hakemi Reference Hakemi1997: 661). Significantly, the seals from both of those sites are rendered in distinct styles and materials which suggest regional workshops using shared iconography. All five examples from Yahya are carved in a gouged style from steatite or chlorite, while at Shahdad all examples of the Pantheon Group were cut in a very fine white stone in a style that is defined first by drilling and then smoothed to create highly modeled forms. One seal of this type has been found in Central Asia at Gonur, where it was certainly imported from the Iranian Plateau, perhaps from near Kerman (Salvatori Reference Salvatori, Salvatori, Tosi and Cerasetti2008; Pittman Reference Pittman, Lamberg-Karlovsky and Cerasetti2014b). All of these seal stones carry only images of female deities.

At KSS the Pantheon Group is found only in Trench V, where it is represented by about fifteen examples. It shows far greater variety, both stylistically and iconographically, than is apparent in the seals of the type from either Yahya or Shahdad. Both male and female deities are represented, and they are shown with wings, horns, and vegetation emerge from their bodies (Fig. 2.9a, b, c). The male deities often wear animal headdresses, in this case in the form of a bird. While some are carved in a gouged style typical of Yahya, others are highly modeled in a volumetric style. Although it is probably premature to draw any firm conclusions, given the fact that only seals come from Yahya and Shahdad and only impressions come, so far, from KSS, it is possible to hypothesize that local traders from Yahya and Shahdad participated in the commercial activity centered at KSS. They returned to their homes or their workshops, where they lost or were buried with their seals. The seals traveled with them. They used them administratively at KSS in the context of trade and exchange to acquire or to deliver desired finished or raw materials. The variety within the Pantheon Group suggests that there were a number of workshops active in the larger region of what is now the modern province of Kerman. The imported seals found at Gonur in the north (Sarianidi Reference Sarianidi2007: figs. 180, 181) and Jalalabad in Fars (Ascalone Reference Ascalone2011: pl. 60 no. 4B14) arrived there from the region of Kerman. At Susa, in addition, one such seal was used administratively (Amiet Reference Amiet and Caubet1996: 128, fig. 6, caption switched with fig. 7), perhaps by a Kermani trader who either sent a sealed package on a shipment to the site or who was there acting in an administrative capacity. The Vase à la Cachette, also from Susa, most likely belonged to a trader, who, along with items of commerce and utility, had six seals that he used in his practice (Pittman in press).

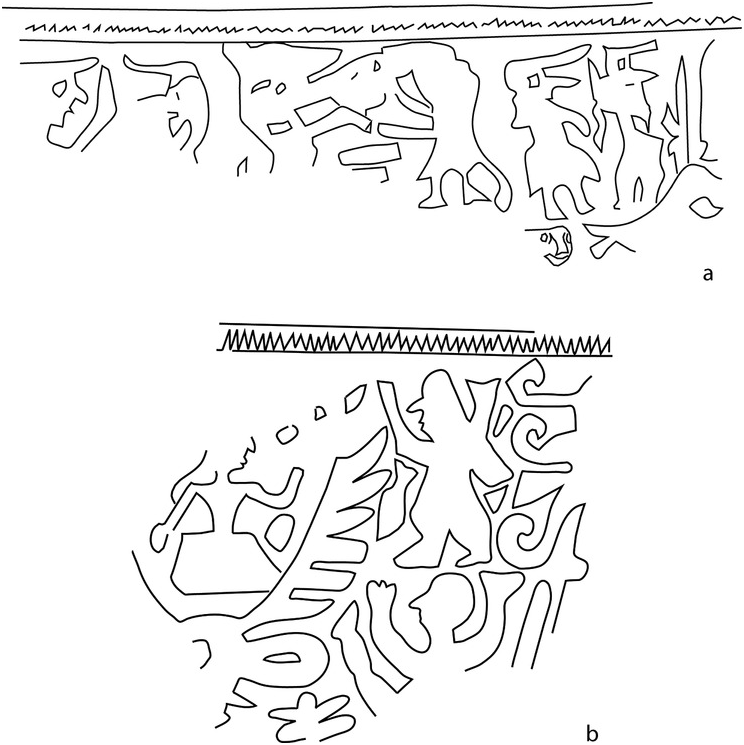

2.9. (a) Drawing of a fragmentary cylinder-seal impression. From the left, a deity with a snake emerging from the shoulder, a male figure wearing a kilt and a cap with pointed brim, and a seated bird; and the shoulder and arm of a larger divine figure with wings and bird headgear. Konar Sandal South, Trench V: 127V402. Preserved height 2.5 cm. Drawing by author; (b) Drawing of a fragmentary cylinder-seal impression. The upper body of a divine figure with vegetation emerging from its body. Konar Sandal South, Trench V: 2005V008. Preserved height 1.5 cm. Drawing by author; (c) Drawing of fragmentary cylinder-seal impression overstamped by a stamp seal. Facing left is a male figure wearing a horned headdress, with long hair, wearing a bull-head pendant around his neck, holding a curved staff in his extended right hand. In front of him are illegible forms. Konar Sandal South, Trench V: 013aV402. Preserved height 1.3 cm.

4. Iranian Community 3: Narrative Seals (Trenches III and V)

Iconography presenting ceremonial events serves as the defining feature of this group which is represented in both trenches. For the most part fragmentary, these seal impressions carry imagery of festivals, or ceremonies that involved both human and fantastic beings (Fig. 2.10a, b). Frequently there is a platform on which figures stand. This is a type that is known in the form of seals from the antiquities market (gathered together and discussed in Pittman Reference Pittman, Bleibtrau and Steymans2014a). Significantly one is also known among the seals from Gonur Tepe (Sarianidi Reference Sarianidi2007: fig. 181), which, like the pantheon examples mentioned above, was certainly imported to the Oxus Civilization, likely on an individual arriving from the Iranian Plateau. The iconography of these seals is extremely rich and provides a singular window into the ritual practices and religious beliefs of the Iranian Plateau Early Bronze Age communities. We see related themes carried on objects from the graves of Shahdad, for example the standard and the fragment of a wall painting (Hakemi Reference Hakemi1997: 649, 663).

2.10. (a) Drawing of a fragmentary cylinder-seal impression. Festival scene with various figures, from the left a crouching lion, a snake, a human figure with animal head raising its hands and standing above various filling motifs; to the left above is a platform and below is a bird facing right toward illegible forms and hollow lozenges. Konar Sandal South, Trench III: KSBtrIII103#006. Preserved height 2.9 cm. Drawing by author; (b) Drawing of a fragmentary cylinder-seal impression. Kneeling male figure facing left with arms raised. Behind are two vessels, in front is a vessel and illegible forms. Konar Sandal South, Trench V: 2005V070. Preserved height 1.5 cm.

5. Iranian Community 4: Gouged-Style Seals (Trenches III and V)

Among the seal impressions from KSS found in both Trenches III and V is a very distinctive type characterized by a gouged style of carving, hence the name. The seals in this group are large, and the carving can be as much as 3–4 millimeters in depth. The iconography is in all cases figural and ranges from fantastic creatures to deities (Fig. 2.11a, b) that could also be included in the Pantheon Group. Similarity, their hatched borders associate them with the Hatched-Border Group discussed above. The composition of the gouged-style seals is in all cases very compact, but the figures adhere to a ground line and are not distorted through interlocking. Also characteristic of the imagery of this group is that the outlines of the figures themselves are created through gouging, resulting in a notched outline effect in the impression. Outside KSS, only one seal (impressions), from Susa, can tentatively be included in this group (Amiet Reference Amiet1972: 1436).

2.11. (a) Drawing of complete impression of a cylinder seal. To the left is a combat scene featuring fantastic creatures including a snake-headed lion engaged with an upside-down goat; the head of a goat emerges from a twisted interlace. To the right a kneeling male faces and holds the hand of a kneeling female facing left. They are surrounded by a twisted interlace. The top and bottom borders are hatched. Konar Sandal South, Trench III: 2005III101. Preserved height 2.75 cm. Drawing by author; (b) Drawing of a fragmentary cylinder-seal impression. To the left is a camel’s head emerging from a central element from which snake heads emerge; to the right is a winged vegetation deity. In the field are illegible forms. Konar Sandal South, Trench V: 029V402. Preserved height 3.3 cm.

6. Iranian Community 5: Linear-Style seals (Trenches III and V)

Among the local styles that were preserved in the administrative residue retrieved from KSS is a type identified as the Linear Group. Although not noticed before this distinctive group appeared, there is one example from the graves at Shahdad which squarely fits within this type (Hakemi Reference Hakemi1997: 661, obj. no. 1226). Of all of the groups identified at KSS so far, the Linear Group can I believe be associated with the official, or ruling, elites within the region. Certainly the most significant seal found at KSS so far can be reconstructed in its entirety through more than fifteen impressions found in Trench V (Fig. 2.12a), one of which is counterstamped by a linear style stamp (see above Fig. 2.1), impressions of which were found in Trench III and Trench V. While no traces of the cylinder itself were found in Trench III, another example of the same theme was found in that trench impressed on a flat biconical tag (Fig. 2.12b). In addition to the theme of the confronted figures, another theme that is preserved through impressions in this style is of a goddess squatting on the back of addorsed horned quadrupeds (Fig. 2.12c). Among the confiscated objects from the looted graves, both confiscated and held in Kerman and in private collections, are a number of actual seals of this type (Pittman in press). There are a number of features that distinguish the type in addition to the distinctive linear manner of the construction of their imagery. Their squat proportions produce a long image field that can accommodate a number of motifs. Another is that when known through the actual seals, they are made of metal (examples in silver, gold, and copper/bronze are known) or less frequently in special stones (lapis or white stone). To judge from the iconography of mortal power apparent in the reconstructed impression from KSS (Fig. 2.12a), this style must have been closely associated with the ruling elites of the site of KSS and the surrounding region. Exactly what role they played in the trade is impossible to determine, but the large number of impressions of the complete Linear Group seal (Fig. 2.12a) suggests that they were active, perhaps both within the commercial system itself and in the administration of that system for the benefit of the local community (for example taxing or otherwise controlling the trade transactions of others).

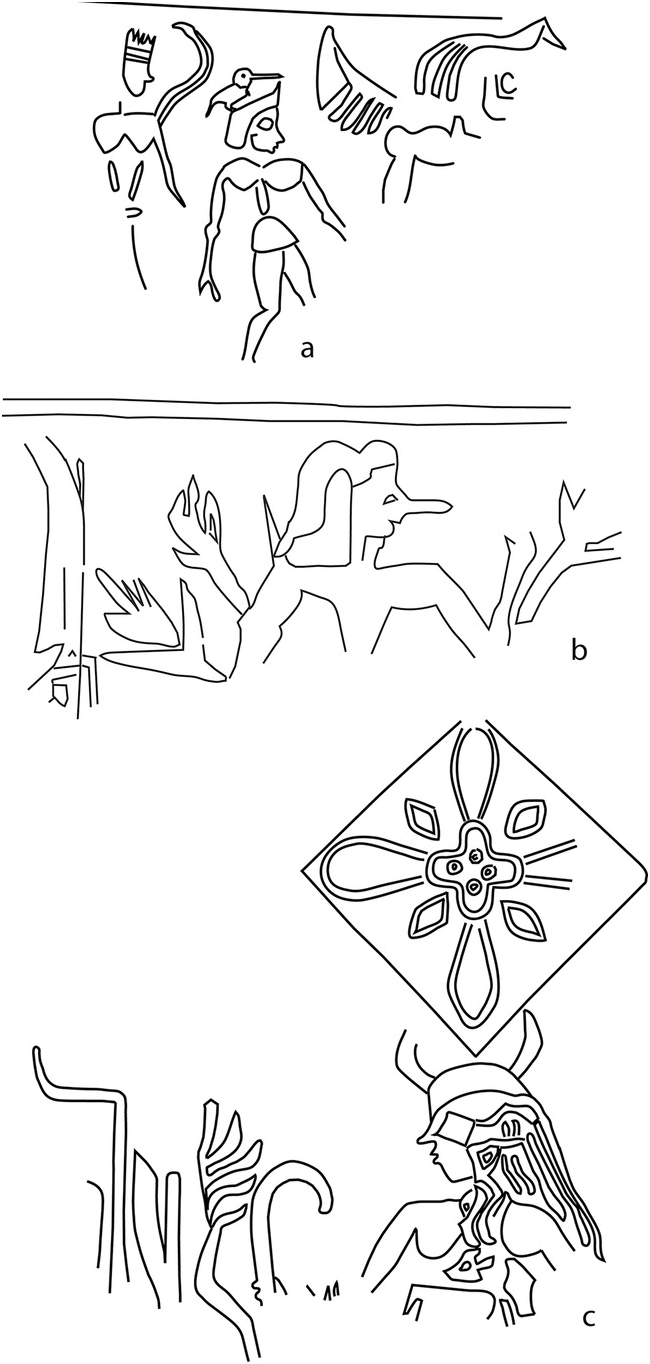

2.12. (a) Composite drawing of a cylinder-seal impression. From the left is a dividing element of star, crescent moon, three dots above an upside-down bird of prey; a long-haired male figure seated on platform extends in his right hand a bow and an arrow pointed downward toward a facing divine figure with long hair and wearing bracelets. A heraldic device consisting of a vertical undulating snake, a bird of prey facing left and grasping a horned snake in its talons. Behind are three male deities all wearing kilts and bracelets striding toward the left. Konar Sandal South, Trench V: 002V401, 002V402, 011V402, 012V402, 016V402. Preserved height 3 cm. Drawing by author; (b) Drawing of cylinder-seal impression representing the order of the figures on the impression. The composition should be read beginning on the left with a seated female figure in front of a tree (?). A star and lozenges. Facing her is a male figure with long hair (or alternatively a group of snakes) and a hero with a flat cap. In the field are lozenges and illegible forms. Konar Sandal South, Trench III: 148aIII306. Preserved height 2.2 cm. Drawing by author; (c) Drawing of fragmentary cylinder-seal impression. Goddess kneeling on the back of a goat with its head turned back. Illegible forms in the field. Konar Sandal South, Trench V: 054V402. Preserved height 1.6 cm.

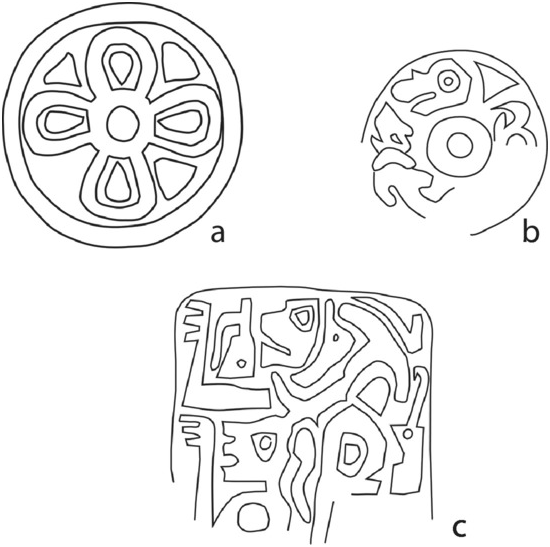

7. Iranian Community 6: Stamp Seals (Trenches III and V)

The last group considered here are stamp seals which are present among the sealing residue from both trenches at KSS. They are of different types and styles, each probably typical of a region on the plateau. Compartmented stamp seals of first stone (Phase II) and then bronze (Phase III) are well documented at the site of Shahr-i Sokhta (Tosi Reference Tosi1983). Compartmented stamps are also abundant in the graves excavated at Gonur in Turkmenistan and are also documented among the looted materials from graves of the region (Baghestani Reference Baghestani1997). Closer to KSS, compartmented stamp seals are known both as objects and through their impressions on ceramic vessels from the graves at Shahdad (Hakemi Reference Hakemi1997). Several of the impressions from KSS on clay sealings appear to have been made from the elaborated heads of pins (Fig. 2.13a). Such pins were confiscated from the looted graves in the region and are also known from Shahdad. Another impression has been made by a metal stamp (Fig. 2.13b), which bears a very close comparison to a stamp seal from the small site of Damin north of the Bampur River (Tosi Reference Tosi1970). In addition to the compartmented stamps, there is a type of stamp imagery that is, to my knowledge at the time of writing, unique to KSS. It features very densely packed figural imagery consisting of human figures, and free-floating arms, bird heads, lion heads, horned animal heads (Fig. 2.13c).

2.13. (a) Drawing of circular stamp-seal impression. Four-petaled design; petals filled with ovoids, and separated by triangles. A raised circular border. Konar Sandal South, Trench III: 139III306. Preserved height 2.1 cm. Drawing by author; (b) Drawing of a fragmentary circular stamp-seal impression. Snake, bird and feline (?) heads surround a central concentric circle. Konar Sandal South, Trench III: 137III306. Preserved height 1.6 cm. Drawing by author; (c) Drawing of a fragmentary square stamp seal. Interlocking composition consists of human figure raising its hand in front of face and wearing a distinctive horned (?) headdress; above are a bird head, a feline head, an upside-down human (?) and a second raised arm which perhaps belongs to the figure below. To the right is a second human figure with long hair (?) facing right toward the head of a horned animal. Illegible forms in the field. Konar Sandal South, Trench III: 132III306. Preserved height 2.2 cm.

There are two instances of countersealing of cylinder impressions with stamps found among the impressions from Trench V. The first (Figs. 2.1 and 2.12a) has been discussed above in relation to the Linear Group. The second is a square stamp with a four-petal design (Fig. 2.9c), which was used to counter-impress a very fine seal of the Pantheon Group. To judge from the imagery and the quality of carving, both cylinders were held by individuals who had access to the finest seal cutters. In addition, the placement of the counterstamp was in each case very careful and intentional. In the case of the fine four-petaled stamp, obviously made from metal, one corner was carefully placed directly above the head of the individual wearing a horned headdress. On the other, both the stamp and the cylinder are carved in the linear style, and the counterstamp was placed to overlap slightly, but not to obliterate the imagery of the cylinder.

From the above discussion it is apparent that different communities from near and far were engaged in shared administrative praxis that was arguably commercial in nature. These distinct communities can be identified through the appearance of their seals, which they used as administrative tools in a variety of ways. Their difference was manifest through morphology of seal type, through iconography, and through style as determined through specific techniques of manufacture. While a microstylistic analysis similar to that undertaken by Jamison or the kind of practice-based analysis undertaken by Green cannot be applied to this data set, it is possible to discern differences that were the result of distinct processes of manufacture. For example, the imagery of the linear-style seals, whether made of metal or stone, was in all cases constructed by a gouging tool of a certain width. The images are essentially drawn using a line of a single width. The gouged style, on the other hand, consists of large seals whose images were formed through a sharp tool that cut at varying depth into the substrate material. Future analysis will consider style as a reflection of method of manufacture in an attempt to discern the degree to which methods of manufacture were shared across communities.

IV Conclusion: Traders in Action

The enormous quantity of luxury raw materials found in the tombs of the Royal Cemetery at Ur make it obvious that during the Late Early Dynastic period boatloads of lapis lazuli, carnelian, copper, silver, gold, alabaster vessels, steatite and chlorite vessels flowed into the city. This is a powerful but indirect testimony to Mesopotamian relations with the Iranian Plateau, which is supported by a contemporary text from Abu Salabikh which states that “the garash-merchant from the (eastern) mountains brought lapis lazuli and silver” (Biggs Reference Biggs1966: 175). The works of Pierre Amiet (Reference Amiet1986), Timothy Potts (Reference Potts1999), and Shereen Ratnagar (Reference Ratnagar2004) have usefully summarized in considerable detail what we know about those relations. As Roger Moorey (Reference Moorey and Curtis1993) states in his most useful article, “Iran: A Sumerian El-Dorado?” there has never been any question that Iran and Mesopotamia had close relations in the third millennium; the problem was, and still is, how to characterize those relations. Were they based on trade, on extraction through force, or diplomatic suasion? In fact, what we can now reconstruct is that all three mechanisms were in play over the span of almost a millennium. Beyond the archaeological evidence, textual evidence describes relations, in terms both of trade and of military and diplomatic vehicles. The richest stream of texts are the literary works, in particular “Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta,” which offers an alternative explanation for the origin of the practice of trade and exchange.

Until the excavations at KSS, there existed no actual physical evidence for the presence of Mesopotamians on the Iranian Plateau. What I have presented here is a summary of the new evidence for their presence within the context of a discussion of the administrative function of seals in the third millennium. What is clear is that within Mesopotamia proper, the function of seals was primarily within internally closed administrative systems that controlled the collection and disbursement of goods within and between institutions and from institutions to individuals dependent on them. Outside Mesopotamia, however, this powerful administrative technology was put to other ends. In the trading context of the Old Assyrian colonies, different ethnic groups employed seals to guarantee and acknowledge various aspects of the economy developed around international trade. While there is never a perfect one-to-one correlation between seal design and ethnicity of the user, there are patterns that link the two, patterns that evolve through the changing identity of the users across generations. On the Iranian Plateau in the Early Bronze, in an environment where writing, if it existed at all, was not used administratively, seals played a vital role in differentiating the various actors who came to central places or markets to acquire, disperse, or exchange raw or semi-processed materials and certainly also finished goods of the types found in the Royal Tombs. Although there is much more to discover before this reconstruction can be accepted as fact, this interpretation of the collections of administrative residue makes sense. We are not looking at a system comparable to Arslantepe, Hacınebi, Ur SIS 8–4, Fara, or Abu Salabikh. A subsequent study will take into account a detailed discussion of the backs of the seal impressions to determine if there is a correlation between seal group and functional type. It can be hoped that iNAA test will also be run on seal impressions in an attempt both to define local clays, and to compare sealings from clays known to be local to Susa and to Ur in the third millennium.

We know from the Mesopotamian evidence that the relations between Mesopotamia and Iran in the third millennium were fluid and that they changed character with the evolving political structure in Mesopotamia itself. The pattern that we can observe now is that during the entire length of the Early Dynastic period beginning in ED I and extending into Late ED III, the relations between Mesopotamia and the east were generally peaceful and of a commercial nature. There is little evidence for conflict and none for colonization. Rather we have, I argue, the traces of individuals from both southern Mesopotamia and Susa who arrived, probably by boat, bringing with them their goods for exchange and their seals. They were ready and eager to acquire what would bring them a profit back home. They were joined by traders and merchants and craftspeople, both local and from other parts of the plateau if we are correct to equate, at least generally, seal group with regional identity. Only further exploration of the still largely unknown region of central Iran will allow us to confirm this notion.

This case study adds to the variety of ways in which the study of seals can shed light on the ancient past. As all of the chapters in this volume illustrate, seals are an immensely rich proxy for behavior and beliefs of ancient people. Seals are a vital trace of administrative and bureaucratic behavior, their iconographies and styles serve as sensitive chronological and regional markers, their imagery provides form to the social, economic, and political concerns as well as religious beliefs of their owners and users, the methods of manufacture shed light on workshop practices and idiosyncratic technologies. With the rich body of material from Konar Sandal South, we have the first instance of the material residue for what can best be interpreted as an interregional marketplace.