Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Chapter1 Accounting for the Industrial Revolution

- Chapter2 Industrial organisation and structure

- Chapter3 British population during the ‘long’ eighteenth century, 1680–1840

- Chapter4 Agriculture during the industrial revolution, 1700–1850

- Chapter5 Industrialisation and technological change

- Chapter6 Money, finance and capital markets

- Chapter7 Trade: discovery, mercantilism and technology

- Chapter8 Government and the economy, 1688–1850

- Chapter9 Household economy

- Chapter10 Living standards and the urban environment

- Chapter11 Transport

- Chapter12 Education and skill of the British labour force

- Chapter13 Consumption in eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century Britain

- Chapter14 Scotland

- Chapter15 The extractive industries

- Chapter16 The industrial revolution in global perspective

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

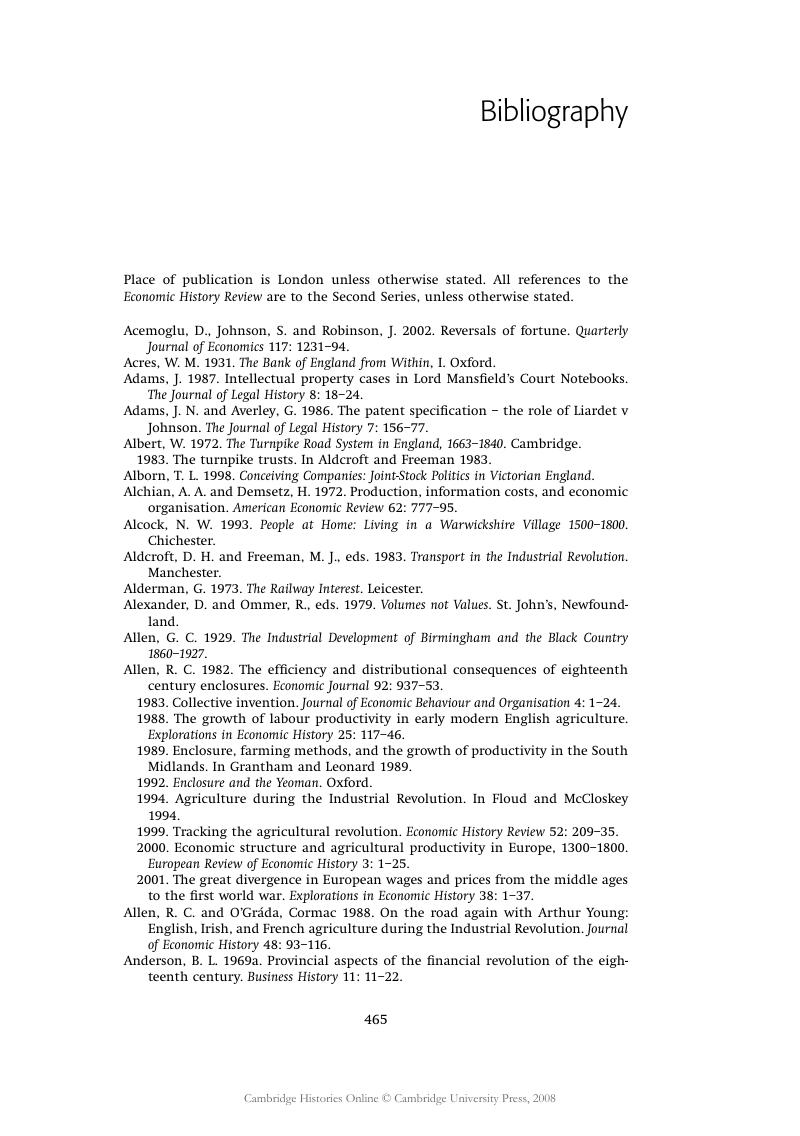

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 28 March 2008

- Frontmatter

- Chapter1 Accounting for the Industrial Revolution

- Chapter2 Industrial organisation and structure

- Chapter3 British population during the ‘long’ eighteenth century, 1680–1840

- Chapter4 Agriculture during the industrial revolution, 1700–1850

- Chapter5 Industrialisation and technological change

- Chapter6 Money, finance and capital markets

- Chapter7 Trade: discovery, mercantilism and technology

- Chapter8 Government and the economy, 1688–1850

- Chapter9 Household economy

- Chapter10 Living standards and the urban environment

- Chapter11 Transport

- Chapter12 Education and skill of the British labour force

- Chapter13 Consumption in eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century Britain

- Chapter14 Scotland

- Chapter15 The extractive industries

- Chapter16 The industrial revolution in global perspective

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- The Cambridge Economic History of Modern Britain , pp. 465 - 505Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2004