Introduction

Dramatic changes in marriage, divorce, cohabitation, and fertility behaviors over the past fifty years have been observed across a wide range of industrialized countries, sometimes referred to as the “second demographic transition” (Lesthaeghe and Neidert Reference Lesthaeghe and Neidert2006). Yet, only within the past several decades has there been growing awareness of the extent to which changes in family demography are unfolding unevenly by socioeconomic status. McLanahan (Reference McLanahan2004) was among the first to identify that differences by socioeconomic status (measured by maternal education) in a range of family behaviors were an important aspect of growing inequality (“diverging destinies”) among children, especially in the United States. Other scholars have increasingly considered differences in various family behaviors by socioeconomic status across other countries (e.g., Härkönen and Dronkers Reference Härkönen and Dronkers2006; Kalmijn Reference Kalmijn2013; Perelli-Harris et al. Reference Perelli-Harris, Kreyenfeld and Kubisch2010), but the extent to which socioeconomic gradients in family behaviors are broadly observed across Western industrialized countries (and whether such gradients may be positive or negative) is less well understood. In this chapter, I examine whether there are differences by socioeconomic status with respect to a range of family behaviors based on the extant literature in the United States and Europe.

The striking changes in family behaviors that have been observed since the middle of the twentieth century across Western countries include a delay and decline in marriage, an increase in cohabitation, a notable rise in divorce rates (followed by a decline in some nations), a high prevalence of repartnering, and a large increase in the proportion of births that occurred outside marriage. Also, there is today striking instability and complexity in family life, as adults are likely to spend time living with more than one partner in marital and/or cohabiting unions, and children often experience several changes in the adults who co-reside with them and/or serve as parental figures in their lives. In this context, men’s involvement with children has become especially precarious, since women still maintain primary responsibility for child-rearing after union dissolution (Goldscheider Reference Goldscheider2000). Taken together, these patterns suggest high levels of instability and perhaps complexity in children’s family arrangements and experiences over childhood and adolescence (Furstenberg Reference Furstenberg2014).

Over the same time period that family patterns have changed, we have also observed a striking increase in overall levels of economic inequality across many industrialized countries, including those that are more egalitarian in values and public policy (OECD 2011b). The increase has been especially stark in the United States – whether measured by wage rates, earnings, family income or wealth (Brandolini and Smeeding Reference Brandolini and Smeeding2006; Gottschalk and Danziger Reference Gottschalk and Danziger2005; Piketty and Saez Reference Piketty and Saez2003). After a strong period of economic growth that benefited individuals across all parts of the income distribution from the mid-1940s to the early 1970s, US inequality rose in the 1980s, slowed somewhat in the 1990s during the economic expansion, then continued to rise as we entered the twenty-first century (Autor, Katz, and Kearney Reference Autor, Katz and Kearney2008; Blank Reference Blank1997). Recent cross-national comparisons show heterogeneity in the levels of inequality observed across European countries (with Scandinavian countries being somewhat less unequal). Compared to industrialized OECD countries, the United States has very high levels of income inequality; in 2013, on average, the top 10 percent of US incomes were fully 19 times higher than those of the bottom 10 percent of incomes, compared to the OECD average of the top 10 percent being about 10 times higher than the bottom 10 percent (OECD 2015). It is important to note that US market income inequality (i.e., before taxes and transfers) is not exceptionally high compared to other European countries (Gini of 0.52, where the range is 0.43 to 0.56 across 19 OECD countries examined in 2010) (Gornick and Milanovic Reference Gornick and Milanovic2015). Rather, the United States does far less than other countries to redistribute income via social policy; after accounting for taxes and transfers, Gini coefficients across these 19 countries ranged from 0.24 in Norway to 0.37 in the United States: Scandinavian countries (Norway, Denmark, and Finland) had the lowest Ginis (0.24–0.26), Anglo-countries (Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United States) had the highest (0.32–0.37), and central/southern/eastern European countries (Czech Republic, Estonia, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Poland, Slovak Republic, Spain, as well as the Republic of Ireland), comprised a group in the middle (0.26–0.33) (Gornick and Milanovic Reference Gornick and Milanovic2015).

Changes in family patterns and economic inequality are not independent, especially in the United States. Indeed, many would argue that the fundamental changes in the economy that have undergirded the overall rise in inequality have also been key drivers of the changes in family patterns. Amidst rapid technological change, deindustrialization, and globalization in labor markets, “good jobs” for those with low-to-moderate education became increasingly scarce (Cherlin Reference Cherlin2014). Starting in the 1980s, scholars began to understand that the limited job opportunities for low-skilled men, especially in poor urban areas, were shaping family behaviors among the disadvantaged (Blank Reference Blank, Cancian and Danziger2009); the decline in “marriageable men” (i.e., men who could get and hold a steady job) was seen as a key aspect of decreasing marriage rates, especially in large US cities (Wilson Reference Wilson1987). Over the same period (since the 1970s), women were increasingly entering the labor market. Women’s employment and earnings provided them with greater economic independence (Oppenheimer Reference Oppenheimer1988), which has been an important factor that typically delays entry into marriage (Sweeney Reference Sweeney2002; Xie et al. Reference Xie, Raymo, Goyette and Thornton2003). Once married, the influence of women’s employment and earnings on the likelihood of divorce is less straightforward, and it seems the greater risk of divorce with higher female earnings is only observed for marriages of lower relationship quality (Sayer and Bianchi Reference Sayer and Bianchi2000; Schoen et al. Reference Schoen, Astone, Kim, Rothert and Standish2002) and for marriages begun in the 1960s and 1970s – but not for marriages begun in the 1990s (Schwartz and Gonalons-Pons Reference Schwartz and Gonalons-Pons2016).

While economic changes and globalization have contributed to rising inequality within (and between) most industrialized countries in recent decades (Firebaugh Reference Firebaugh, Scott and Kosslyn2015), we know that the ultimate circumstances of individuals and families also depend on the level and type of policy supports and the degree of “decommodification” (i.e., citizens’ ability to have sufficient income independent of the market) across welfare states (Esping-Andersen Reference Esping-Andersen1990). Overall, means-tested and targeted benefits are less effective for reducing poverty and inequality as compared to universal social insurance benefits (Korpi and Palme Reference Korpi and Palme1998). As noted above, the Scandinavian countries typically offer more generous welfare policies that provide higher levels of support and allow parents to better balance work and family obligations, as compared to Anglo-countries (especially the United States) which offer minimal support, with central and southern European countries falling somewhere in between (Gornick, Meyers, and Ross Reference Gornick, Meyers and Ross1997). There is extensive research demonstrating that indeed social policies across countries have an important influence on levels of inequality in economic outcomes such as employment, earnings, and income (e.g., Hegewisch and Gornick Reference Hegewisch and Gornick2011; Mandel and Semyonov Reference Mandel and Semyonov2005).

At the same time, differences in family patterns may also contribute to increasing economic inequality, both within and across generations – at least in the United States (M. Martin Reference Martin2006; McLanahan Reference McLanahan2004; McLanahan and Percheski Reference McLanahan and Percheski2008). Within the United States, changes in family structure – especially the rise in divorce and single parenthood – are shown to have increased family income inequality, although there is a range in the estimates about how big a factor these have been (McLanahan and Percheski Reference McLanahan and Percheski2008). Also, increasingly homogamous marriages at both the low and high ends of the income distribution were observed from 1960 to the early 2000s (Schwartz and Mare Reference Schwartz and Mare2005), and the growing association in spouses’ earnings served to significantly increase aggregate-level income inequality in the United States (Schwartz Reference Schwartz2010). To my knowledge, there has been less research about how family patterns per se have driven levels of inequality in other countries. The prevalence of single parenthood has been linked with higher inequality across sixteen European countries between 1967 and 2005, holding constant the level of female employment (which is itself associated with reduced inequality) (Kollmeyer Reference Kollmeyer2013). An analysis of Denmark shows that greater educational assortative mating has increased inequality, but due to shifting educational distributions by gender (i.e., education increasing for both men and women – but more so for women) rather than partner choice (Breen and Andersen Reference Breen and Andersen2012). Certainly, families with greater socioeconomic resources are able to make greater investments (of both time and money) in their children (Kalil Reference Kalil, Amato, Booth, McHale and Van Hook2015; Kalil, Ryan, and Corey Reference Kalil, Ryan and Corey2012; Lareau Reference Lareau2003), and these differential investments may be an important factor in growing inequality, especially across generations (Lundberg, Pollak, and Stearns Reference Lundberg, Pollak and Stearns2016; Reeves Reference Reeves2017). And as Cooke (see Chapter 11) describes, countries differ greatly in the share of national resources that are invested in families; when countries provide greater baseline support, there is likely less variation by parents’ income in how much they invest in children. Nevertheless, differential parental investments have a long-lasting effect on the development and attainment of the next generation, and inequality therein (Heckman Reference Heckman2007; Yeung, Linver, and Brooks-Gunn Reference Yeung, Linver and Brooks–Gunn2002).

Thus, overall, it seems reasonable to expect a reciprocal and dynamic relationship between inequality and family patterns: Aggregate-level inequality affects family behaviors and outcomes, and differential family patterns further reify inequality and stratification (McLanahan and Percheski Reference McLanahan and Percheski2008). In the remainder of this chapter, I will (a) provide a brief review of key changes in family patterns that have occurred over the past half-century in the United States and Europe, and then (b) summarize the literature about the extent to which differentials in family patterns by socioeconomic status are observed.

Changing Family Patterns

Across most Western industrialized countries, a number of changes in family behaviors occurred, beginning in the 1960s. Often referred to as the “second demographic transition,” there has been a similarity in the changes across Western countries that included delayed marriage, a disconnection between marriage and childbearing, a diversity of relationships and living arrangements, and declining fertility to below replacement level (Lesthaeghe Reference Lesthaeghe2010). While not uniform across all countries or European regions (see Chapter 4), the basic changes in family behaviors fall into predictable patterns, as described below.

Marriage and Cohabitation

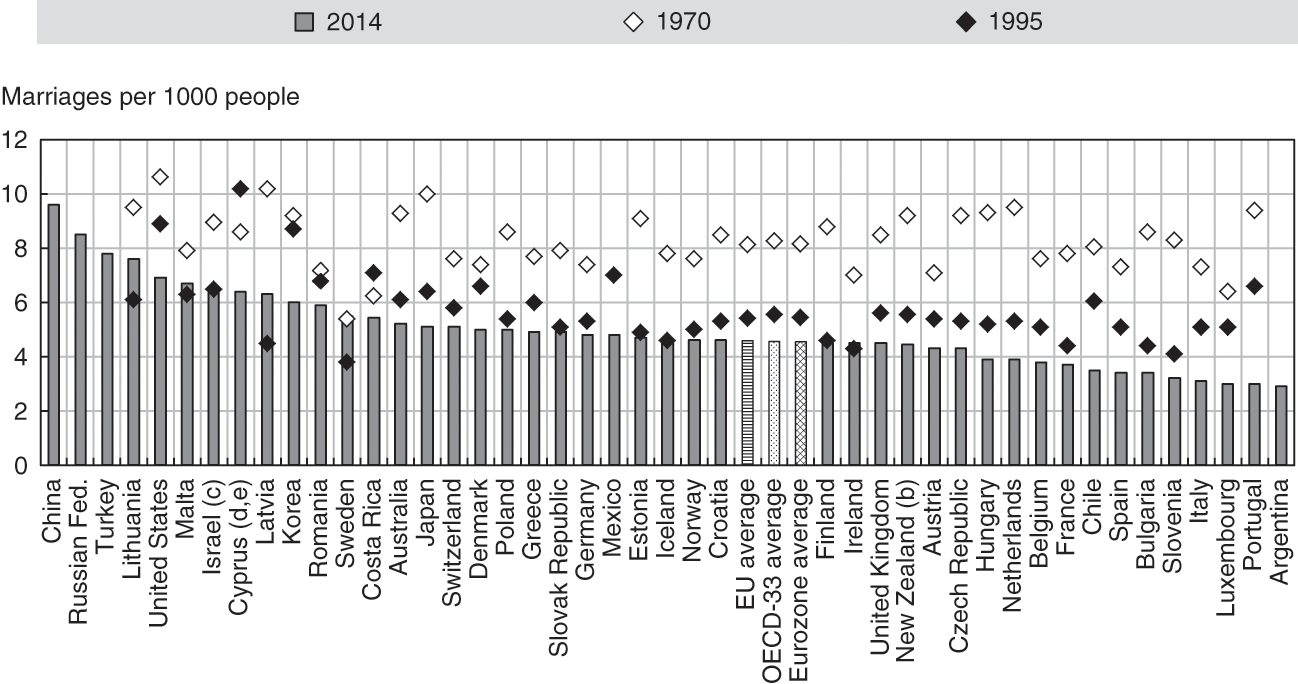

At the core of changes in family life over the past half-century have been shifts in the nature of union formation and marital behavior. Marriage has become less central to the life course, both because individuals are marrying later and a small – but perhaps rising – fraction are not marrying at all (Cherlin Reference Cherlin2009). As shown in Figure 1.1, crude marriage rates have significantly declined in most OECD countries over the period from 1970 to 2014.

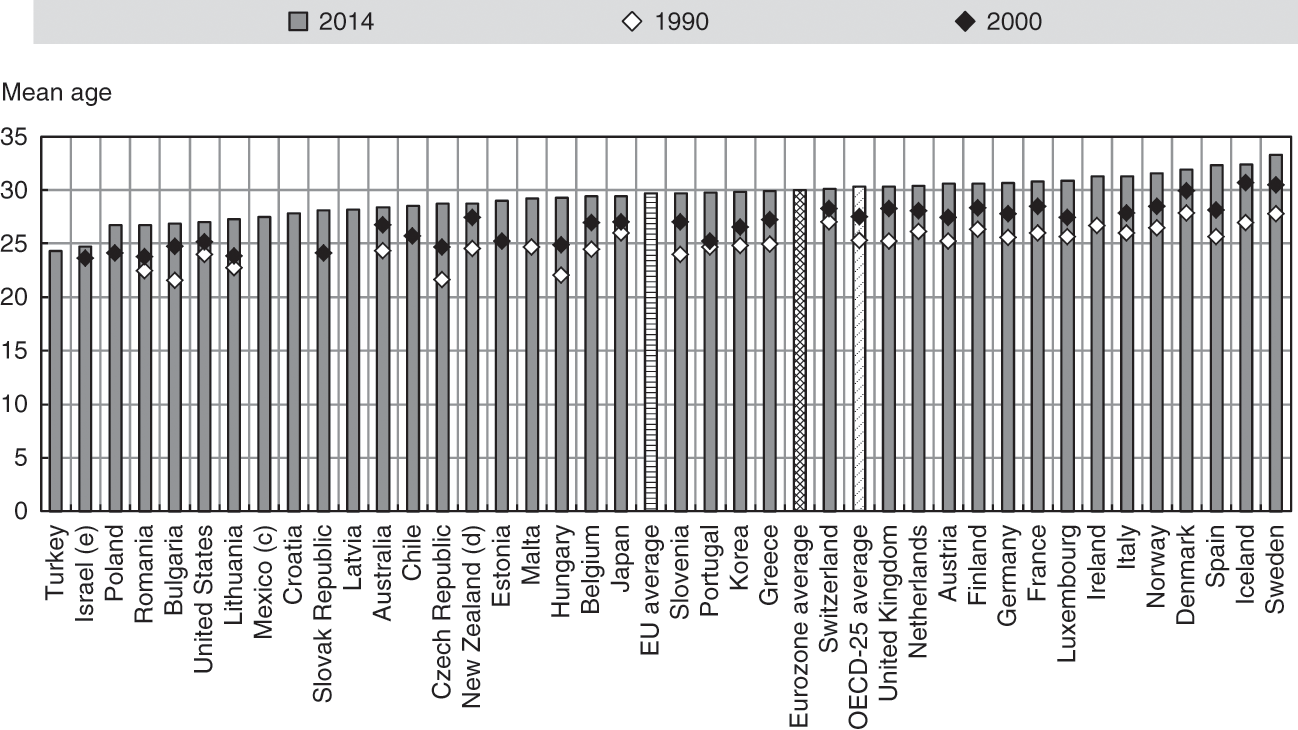

Across nearly all OECD countries, age at first marriage has increased over the past two decades (see Figure 1.2); women’s mean ages at marriage now range from the mid-twenties in some Eastern European countries to the early thirties in some Scandinavian countries. In the United States, the median age at first marriage has never been higher than since data were first collected in 1890 – age 27.4 for women and 29.5 for men in 2015 (US Census Bureau 2016).

Figure 1.2 Women’s mean age at first marriage across OECD countries, 1990–2014.

Also, cohabitation has increased such that today over 60 percent of US women have ever cohabited (Manning Reference Manning2013), and the fraction is even higher in most European countries. Cohabitation has essentially replaced marriage as a first union for the majority of young adults, as, at least in the United States, individuals have been entering a first union at about the same average age over the past twenty years (Manning, Brown, and Payne Reference Manning, Brown and Payne2014). The diverse meanings and experiences of cohabitation are an important factor in both the United States and Europe, as cohabitation may be a precursor to – or a substitute for – legal marriage for different groups or at different stages of the life course for the same individuals (Heuveline and Timberlake Reference Heuveline and Timberlake2004; Hiekel, Liefbroer, and Poortman Reference Hiekel, Liefbroer and Poortman2014; Perelli-Harris et al. Reference Perelli-Harris, Mynarska and Berghammer2014; Seltzer Reference Seltzer2004). A growing proportion of first births now occur within cohabiting unions across European countries (Perelli-Harris et al. Reference Perelli-Harris, Kreyenfeld and Sigle-Rushton2012) and the United States (Curtain, Ventura, and Martinez Reference Curtain, Ventura and Martinez2014). Further, many cohabiting households include children who are born to couples while living together or that one or the other partner has from a prior relationship (Kennedy and Bumpass Reference Kennedy and Bumpass2008; Thomson Reference Thomson2014).

Divorce

Divorce has been rising across most European countries over recent decades, and there is notable heterogeneity in the patterns, causes, and consequences (Amato and James Reference Amato and James2010). Divorce in the United States has historically been much higher than in other Western countries, and the best estimates suggesting that about half of all first marriages will end in divorce in the United States (Amato Reference Amato2010). Figure 1.3 shows crude divorce rates across OECD countries for 1970–2014, ranging from the lowest European levels today in the Republic of Ireland and Italy to the highest in Lithuania, Denmark, and the Russian Federation. In many countries, divorce rates rose between 1970 and 1995 and then declined between 1995 and 2014. Across European countries, divorce tends to be higher in the West and North versus lower in the East and South.

Figure 1.3 Crude divorce rates across OECD countries, 1970–2014.

Repartnering

As many unions now dissolve, it is increasingly likely that individuals will have more than one partner over their life course, either by marriage and/or cohabitation. Repartnering provides a new opportunity to share economic resources, give/receive emotional support, and experience companionship and sexual intimacy, and thus may offset some of the negative consequences of divorce (Amato Reference Amato2010). Yet, when children are involved, repartnered relationships may be more complicated or less “institutionalized” than first partnerships (Cherlin and Furstenberg Reference Cherlin and Furstenberg1994). Across Europe and the United States, there has been a notable rise in repartnering since the 1970s, although there is substantial cross-country variation (Gałęzewska Reference Galezewska2016). Figure 1.4 (from Gałęzewska Reference Galezewska2016) shows the cumulative proportion of women who repartner within ten years of union dissolution, across three birth cohorts. There has been a dramatic rise in repartnering over time, as, in most countries, women born 1965–1974 are much more likely to repartner than women born 1945–1954 or 1955–1964; the exception here being the United States, where repartnering was already high in the earliest cohort. For the most recent cohort, the majority of women will repartner within ten years after union dissolution across twelve of the fifteen countries examined (the exceptions being Bulgaria, Lithuania, and Poland), and most of those unions will be cohabitations; at the same time, it is important to note that selection processes may affect the high rate of repartnering for the recent cohort, as these women were quite young at union dissolution and may differ from women who entered unions at older ages and/or had longer-lasting unions (Gałęzewska Reference Galezewska2016).

Figure 1.4 Cumulative proportions of women repartnering ten years after union dissolution by cohort

Nonmarital Childbearing

Along with the changes in marriage patterns has been a sharp increase in childbearing outside marriage across most Western industrialized countries. In the United States, 40 percent of births are today outside legal marriage (Hamilton, Martin, and Osterman Reference Hamilton, Martin and Osterman2016). As shown in Figure 1.5, the OECD-27 average for 2014 was also 40 percent, but this belies notable variation across countries – from only 7 percent in Greece to more than 50 percent in Belgium, Bulgaria, Denmark, Estonia, France, Iceland, Norway, Slovenia, and Sweden.

While “traditional” family formation typically followed a linear course – first dating, then marriage, and then childbearing – the rise in nonmarital childbearing (along with concomitant changes in union formation) has yielded a range of complex and diverse family arrangements. This is especially true for disadvantaged individuals in the United States and the United Kingdom, who are likely to have children outside marriage in relationships that are likely to break up (Kiernan et al. Reference Kiernan, McLanahan, Holmes and Wright2011; Mincy and Pouncy Reference Mincy, Pouncy, Horn, Blankenhorn and Pearlstein1999). In Europe, nonmarital childbearing occurs more often within cohabitation, and cohabitation is often not differentiated from legal marriage in policy or research, especially in countries where cohabitation is quite common.

Much of the recent increase in nonmarital childbearing can be attributed to births to cohabiting couples, especially in European countries (Thomson Reference Thomson2014). The majority of nonmarital births between 2000 and 2004 occurred to cohabiting couples in France and Norway, and 30–40 percent in Austria, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom (Perelli-Harris et al. Reference Perelli-Harris, Kreyenfeld and Kubisch2010). In the United States, 18 percent of all children were born to cohabiting mothers between 1997 and 2001 (Kennedy and Bumpass Reference Kennedy and Bumpass2008), and the most recent US data indicate that fully 58 percent of nonmarital births between 2006 and 2010 occurred to cohabiting couples (Curtain, Ventura, and Martinez Reference Curtain, Ventura and Martinez2014). At the same time, being born to cohabiting parents does not mean that children necessarily enter into a stable union, as many such unions are highly unstable – even more so in the United States than in other nations (Kiernan Reference Kiernan1999; Osborne and McLanahan Reference Osborne and McLanahan2007). Growing evidence clearly shows that children born to married parents have much more stable families than children born to cohabiting parents across European countries as well (DeRose et al. Reference DeRose, Lyons-Amos, Wilcox and Huarcaya2017; Sánchez Gassen and Perelli-Harris Reference Sánchez Gassen and Perelli-Harris2015; Henz and Thomson Reference Henz and Thomson2005; Liefbroer and Dourleijn Reference Liefbroer and Dourleijn2006). Recent research using data from the Generations and Gender Surveys and other comparable sources across Europe and the United States suggests that children born to cohabiting parents are far more likely to see their parents separate by age 15 (ranging from 13 percent in Georgia to fully 73 percent in the United States), compared to those born to married parents (ranging from 8 percent in Georgia to 34 percent in the United States and 36 percent in the Russian Federation) (Andersson, Thomson, and Duntava 2016). In other words, even in more egalitarian countries, marriage in the context of childbearing is associated with greater union stability (perhaps due to the selection of those who choose to have children within legal marriage versus cohabitation).

Multipartnered Fertility

Amidst high levels of union dissolution and nonmarital childbearing, a large fraction of adults today have (or will have) biological children by more than one partner, sometimes referred to as “multipartnered fertility.” All things being equal, overall fertility rates are shown to be higher in countries where policies allow women to better balance work and family commitments (Castles Reference Castles2003; Duvander, Lappegård, and Andersson Reference Duvander, Lappegård and Andersson2010; Rindfuss et al. Reference Rindfuss, Guilkey, Morgan and Kravdal2010), but multipartnered fertility will also be higher in contexts of high union dissolution (Thomson Reference Thomson2014). Recent studies focused on the United States have identified that a sizeable fraction of individuals across various demographic groups have children by more than one partner (Guzzo and Dorius Reference Guzzo and Dorius2016), including low-income teenage mothers (Furstenberg and King Reference Furstenberg and King1999), national samples of adult men (Guzzo Reference Guzzo2014; Guzzo and Furstenberg Reference Guzzo and Furstenberg2007b), adolescent and early adult women (Guzzo and Furstenberg Reference Guzzo and Furstenberg2007a), unwed parents in large US cities (Carlson and Furstenberg Reference Carlson and Furstenberg2006), and mothers receiving welfare (Meyer, Cancian, and Cook Reference Meyer, Cancian and Cook2005).

This phenomenon is not unique to the United States, and a growing literature has explored multipartnered fertility across European contexts, especially with respect to its prevalence and predictors. In a study comparing two Anglo-countries and two Nordic countries, Thomson et al. (Reference Thomson, Lappegård, Carlson, Evans and Gray2014) found that the fraction of all mothers who have children with two or more fathers was 12 percent in Australia, 16 percent in Norway, 13 percent in Sweden and 23 percent in the United States; the higher prevalence in Australia and the United States is likely due to the greater proportion of births that occur to lone mothers in these two countries (Thomson Reference Thomson2014; Thomson et al. Reference Thomson, Lappegård, Carlson, Evans and Gray2014). Other studies have shown that childbearing across partnerships, or “stepfamily childbearing” (Thomson Reference Thomson2014), is not uncommon in Sweden (Holland and Thomson Reference Holland and Thomson2011; Vikat, Thomson, and Hoem Reference Vikat, Thomson and Hoem1999) and Norway (Lappegård and Rønsen Reference Lappegård and Rønsen2013).

Family Instability for Children

Taken together, at the intersection of patterns of union formation and dissolution with fertility behavior, are the family experiences of children. Within the United States, a growing literature has examined the prevalence and consequences of family instability for children. While much of the early literature focused on being in particular family types – first, intact versus nonintact families, then various longitudinal categories of family structure during childhood (e.g., Astone and McLanahan Reference Astone and McLanahan1991; Cherlin Reference Cherlin1999; McLanahan and Sandefur Reference McLanahan and Sandefur1994) – more recent studies have identified family transitions or instability (i.e., changes in family type) as an important factor predicting children’s well-being. This literature consistently shows that greater family instability is associated with disadvantageous outcomes for children across a range of academic and behavioral domains (Davis et al. Reference Davis, Schoppe-Sullivan, Mangelsdorf and Brown2009; Fomby and Cherlin Reference Fomby and Cherlin2007; Osborne and McLanahan Reference Osborne and McLanahan2007).

There is a growing literature about the prevalence of family instability experienced in other industrialized countries, including several cross-national, comparative studies. Using data from the UN’s Fertility and Family Surveys (FFS), Andersson (Reference Andersson2004) and Heuveline, Timberlake, and Furstenberg (Reference Heuveline, Timberlake and Furstenberg2003) found that the United States is an outlier with respect to family instability, with fully half of US children experiencing their parents’ union dissolution by age 15; at the other end of the spectrum, only about one in ten of children in Italy will see their parents’ union dissolve by age 15, while most other countries in Western and Eastern Europe fall somewhere in between – with about one quarter to one third of children experiencing the dissolution of their parents’ union by age 15. The United States has a higher fraction of children born to single (i.e., not cohabiting or married) mothers than other countries; however, across nearly all countries, including the United States, children are more likely to live with a single parent as a result of parental separation than being born to an unpartnered mother.

Swedish register data (i.e., data about the entire population of Sweden) offer a particularly rich source of information about parents’ union histories (and hence children’s family structure), including cohabitation, which is often not accurately or regularly measured in surveys. Thomson and colleagues have several papers exploring family (in)stability in Sweden, finding that one quarter to one third of Swedish children have experienced their parents’ union dissolution by age 15, depending on whether survey data or register data are used (Kennedy and Thomson Reference Kennedy and Thomson2010; Thomson and Eriksson Reference 320Thomson and Eriksson2013).

Research suggests that children who live apart from their biological fathers do not fare as well on a range of outcomes as children who grow up with both biological parents, especially within stable married families (Amato and Anthony Reference Amato and Anthony2014; McLanahan, Tach, and Schneider Reference McLanahan, Tach and Schneider2013). The research evidence is especially strong in the United States, although parents’ union dissolution has been linked with various adverse outcomes across European and Anglo-countries as well (see Chapter 6; Härkönen, Bernardi, and Boertien Reference Härkönen, Bernardi and Boertien2017; McLanahan, Tach, and Schneider Reference McLanahan, Tach and Schneider2013). There is mixed evidence about whether there is an educational gradient in the effects of single parenthood on children’s outcomes; recent reviews of the literature (see Chapter 6; Bernardi et al. Reference Bernardi, Härkönen, Boertien, Rydell, Bastaits and Mortelmans2013) note that some studies show single parenthood to be more detrimental for children of higher educated parents, while other studies show single parenthood to have greater negative consequences for children of lower education.

Children in single-mother families are often deprived of two types of resources from their fathers: Economic (money) and relational (time) (Thomson, Hanson, and McLanahan Reference Thomson, Hanson and McLanahan1994; Thomson and McLanahan Reference Thomson and McLanahan2012). The economic circumstances can be most easily quantified: Single-parent families with children have a significantly higher poverty rate (43 percent in 2015) than two-parent families with children (10 percent in 2015) (DeNavas-Walt, Proctor, and Smith Reference DeNavas-Walt, Proctor and Smith2010), and an extensive US literature shows that living in poverty has adverse effects on child development and well-being as well as adult socioeconomic attainment (Duncan and Brooks-Gunn Reference Duncan and Brooks-Gunn1997; Duncan, Ziol-Guest, and Kalil Reference Duncan, Ziol-Guest and Kalil2010; Duncan et al. Reference Duncan, Magnuson, Kalil and Ziol-Guest2012; Hair et al. Reference Hair, Hanson, Wolfe and Pollak2015). Yet, it is important to recognize the effects of family structure on economic well-being are not necessarily (or entirely) causal, though there is evidence of some causal effect of marriage on family income (Sawhill and Thomas Reference Sawhill and Thomas2005; Waite and Gallagher Reference Waite and Gallagher2000). Also, at the aggregate level, geographic regions with a higher proportion of intact families are shown to experience greater economic growth (Lerman et al. Reference Lerman, Price and Wilcox2017) and higher intergenerational mobility (Chetty et al. Reference Chetty, Hendren, Kline and Saez2014a). Children in single-parent families also receive less parental attention and emotional support from their fathers: Nonresident fathers see their children less often than resident fathers, and lack of interaction decreases the likelihood that a father and child will develop a close relationship (Carlson Reference Carlson2006; Seltzer Reference Seltzer1991).

Overall, dramatic changes in family behaviors have occurred over the past half-century, resulting in new and more diverse patterns of family experiences for adults and for the children with whose life courses they overlap. While there is some variation in breadth and scope, these patterns are generally observed across Western industrialized countries. In the next section, I turn to the extent to which these family patterns appear to systematically differ by socioeconomic status.

Family Change and Inequality

Although the “second demographic transition” – with the incumbent changes in marriage, divorce, cohabitation, and fertility – has been recognized as occurring across a wide range of industrialized countries (Lesthaeghe Reference Lesthaeghe, Mason and Jensen1995, Reference Lesthaeghe2010), only within the past fifteen years has there been clear recognition of the extent to which changes in family demography are unfolding unevenly across the income distribution. McLanahan’s Reference McLanahan2004 presidential address at the Population Association of America noted that differences in family behaviors (including divorce, single parenthood, maternal employment, and fathers’ involvement with children) by socioeconomic status (measured by mothers’ education) were an important aspect of growing inequality among children, or what she called “diverging destinies” (McLanahan Reference McLanahan2004; McLanahan and Jacobsen Reference McLanahan, Jacobsen, Amato, Booth, McHale and Van Hook2015). Although the bulk of her evidence was focused on the United States, she included international comparisons for maternal age, maternal employment, and single motherhood by mothers’ education for six European countries, using data from the Luxembourg Income Study; in all cases, she found notable gaps by education in the prevalence of each. Subsequent studies have provided additional evidence about the extent to which family demographic patterns diverge by socioeconomic status (and whether this divergence may be increasing).

Marriage

Extensive evidence has shown that the retreat from marriage is much more pronounced among the less-educated in the United States. Those with a college education are much more likely to marry compared to those with less (Cherlin Reference Cherlin2009; Goldstein and Kenney Reference Goldstein and Kenney2001; White and Rogers Reference White and Rogers2000). An educational gradient in marriage is less consistently observed across European countries, although whether, and in what direction, a gradient is observed may depend on the degree of gender segregation within countries (Kalmijn Reference Kalmijn2007, Reference Kalmijn2013). Analyzing union formation across Canada, Italy, Sweden, and the United States in the early/mid-1990s, Goldscheider, Turcotte, and Kopp (Reference Goldscheider, Turcotte and Kopp2001) found that the educational gradient for marriage was steepest in the United States, where those with a college education were more likely – and those with below high school were less likely – to marry than those with a high school degree. There was no discernible gradient in Canada or Sweden, and in Italy, those with both lower education and with higher education were more likely to marry than those with a high school education. Using data from the European Social Survey from 2002 to 2010 for twenty-five countries, Kalmijn (Reference Kalmijn2013) found that for women, higher education is negatively related to marriage when gender roles are highly segregated but is positively related to marriage in gender-egalitarian countries; in other words, highly educated women are more likely to marry when societal expectations about marriage include continued involvement in the paid labor market. For men, there is a positive gradient overall, but it is weaker in traditional countries and more strongly positive in egalitarian societies. At the same time, higher education is associated with a delay in marriage in a recent study across fifteen Western countries (Perelli-Harris and Lyons-Amos Reference Perelli-Harris and Lyons-Amos2016).

Divorce

There is mixed evidence about how education is related to divorce, with some countries showing a positive gradient, others a negative gradient, and some no detectable gradient. In the United States, a notable negative educational effect on divorce has emerged since the 1970s, as those with a college degree are much less likely to divorce then their less-educated counterparts (S. P. Martin Reference Martin2006; Raley and Bumpass Reference Raley and Bumpass2003; White and Rogers Reference White and Rogers2000). Using data on first marriages in seventeen countries from the Fertility and Family Surveys with event-history techniques, Härkönen and Dronkers (Reference Härkönen and Dronkers2006) found that higher education is associated with a higher risk of divorce in France, Greece, Italy, Poland, and Spain and with a lower risk of divorce in Austria, Lithuania, and the United States; there is no educational gradient in divorce observed in Estonia, Finland, West Germany, Hungary, Latvia, Sweden, and Switzerland – and for some models in Flanders and Norway. They attributed their disparate findings to the social and economic costs of divorce, which vary over time and across countries. They also found that the gradient is more positive in countries with more generous welfare policies, which they suggested means that social benefits may promote marital stability among the socioeconomically disadvantaged. Kalmijn (Reference Kalmijn2013) also considered divorce in his paper on the educational gradient in marriage across twenty-five European countries; he found that overall, men – but not women – with a higher education were less likely to get divorced (conditional on marriage). However, the association differed by gender attitudes within countries – a higher education was associated with a lower likelihood of divorce in gender-egalitarian societies, but with a higher likelihood of divorce in more gender-traditional countries. In a meta-analysis of fifty-three studies of education and divorce across Europe, Matysiak, Styrc, and Vignoli (Reference Matysiak, Styrc and Vignoli2014) found a generally positive socioeconomic gradient in divorce – but with variation across countries – and they note that the relationship between education and divorce has weakened over time as divorce has become more common and as women have increasingly entered the labor force.

In a recent paper that conjointly considers union formation and dissolution patterns as linked to socioeconomic status, Perelli-Harris and Lyons-Amos (Reference Perelli-Harris and Lyons-Amos2016) used data across fifteen countries with latent-class analysis to examine partnership trajectories. They found that education is consistently associated with a delay in marriage, but there is less consistent evidence for an education gradient in stable cohabitation or union dissolution. In other words, a higher education is associated with marrying later but not with cohabiting or the likelihood of breaking up. Overall, they find that country context is more important (and increasingly so) then individual-level education in predicting partnership patterns, with country context reflecting the unique combination of social, cultural, political, and economic factors within particular nations.

Repartnering

Repartnering only occurs once unions have been entered and exited, and we know that there are numerous factors that affect the likelihood of such, including both social and economic characteristics (Lyngstad and Jalovaara Reference Lyngstad and Jalovaara2010; Xie et al. Reference Xie, Raymo, Goyette and Thornton2003). While repartnering has increased across most Western countries, following rising union dissolution rates, there does not appear to be a consistent socioeconomic gradient. In the United States, where repartnering rates are highest, greater education (especially college) is associated with a higher likelihood of remarriage – but with a lower likelihood of cohabiting with a new partner (McNamee and Raley Reference McNamee and Raley2011). In the Netherlands, education is associated with a greater likelihood of repartnering (either marriage or cohabitation) for men but not for women (de Graaf and Kalmijn Reference De Graaf and Kalmijn2003; Poortman Reference Poortman2007). One recent study in Flanders that considered the characteristics of new partners found that higher educated men are more likely to repartner with a childless partner (versus no union) but not with a partner who has a child (Vanassche et al. Reference Vanassche, Corijn, Matthijs and Swicegood2015); this study also found no effects of education on repartnering for women.

Nonmarital Childbearing

We know that nonmarital childbearing in the United States is strongly associated with socioeconomic disadvantage (Ellwood and Jencks Reference Ellwood, Jencks and Neckerman2004; McLanahan Reference McLanahan, Carlson and ngland2011). Childbearing within cohabitation is shown to follow a clear socioeconomic gradient within eight European countries, although the gap by education has not necessarily increased over time (Perelli-Harris et al. Reference Perelli-Harris, Kreyenfeld and Kubisch2010); these authors find that conceptual expectations from second demographic transition theory cannot account for the gradient across countries and over time. Instead, the negative socioeconomic gradient appeared to emerge from both economic and social changes; in particular, changes in the labor market brought both greater economic uncertainty and higher employment among women, and at the same time, social values and norms were changing that increased the acceptability of certain family behaviors. Kennedy and Thomson (Reference Kennedy and Thomson2010) also considered births to single and cohabiting women in Sweden, and they found a small and persistent gap by education in the fraction of births to single (unpartnered) women; of births to women with less than secondary education (tertiary education), 5 percent (2 percent) were to single mothers in the 1970s and 6 percent (3 percent) in the 1990s. While births to cohabiting women rose for all women, the relative gap by education remained similar over this time period: For women with less than secondary education (tertiary education), the fraction of births to cohabiting women rose from 45 percent (30 percent) in the 1970s to 59 percent (38 percent) in the 1990s – thus the ratio of high-to-low education was similar (at 1.5–1.6) at both time points.

Multipartnered Fertility

In the United States, we know that multipartnered fertility is much more common among socioeconomically disadvantaged men and women (Cancian, Meyer, and Cook Reference Cancian, Meyer and Cook2011; Carlson and Furstenberg Reference Carlson and Furstenberg2006; Guzzo and Dorius Reference Guzzo and Dorius2016). Thomson et al. (Reference Thomson, Lappegård, Carlson, Evans and Gray2014) find a similar pattern in their study of Australia, Norway, Sweden, and the United States: There is a negative educational gradient, as higher education is associated with a lower chance of having a subsequent birth to a different father. In their detailed analyses of Norwegian register data, Lappegård and Rønsen (Reference Lappegård and Rønsen2013) paint a more complicated picture, finding that multipartnered fertility is related to both socioeconomic disadvantage and advantage. The former can be attributable to the fact that the risk of union dissolution is higher among those who are socioeconomically disadvantaged, while the latter is due to the fact that, conditional on having broken up, the chance of repartnering is higher among the socioeconomically advantaged. Indeed, union instability during the childbearing years can serve as an “engine of fertility,” because parity progression occurs more quickly in new partnerships (Thomson et al. Reference Thomson, Winkler-Dworak, Spielauer and Prskawetz2012).

Family Instability for Children

While there has been less research focused on socioeconomic gradients in family instability for children in European contexts, several recent papers have provided important new insights. In work in progress by Carlson et al. (Reference Carlson, Raymo, VanOrman and Lim2014) analyzing fifteen industrialized countries, the authors find that between birth and age 15, US children spend on average five years living with a single (unpartnered) mother, compared to one to three years in all other countries (Russia being the second highest at three years). Further, there is a notable educational gradient in family instability; across all countries examined, children spend a higher number of years living with both parents if the mother has a higher education, but the gap in family stability by maternal education is greatest in the United States.

Kennedy and Thomson (Reference Kennedy and Thomson2010), using data from the Swedish Level of Living Survey, found some evidence of a growing gap in family instability by parental education in Sweden from the 1970s to the 1990s, although the magnitude of the gradient was far less than that observed in the United States. Given the strong association noted earlier between growing up with two biological parents and healthy child development (McLanahan, Tach, and Schneider Reference McLanahan, Tach and Schneider2013), this may have broader implications for inequality. Yet, one recent paper focused on Germany, Italy, the United Kingdom, and the United States found that while indeed growing up in a nonintact family was associated with lower socioeconomic attainment, this did not explain aggregate-level differences in inequality across countries (Bernardi and Boertien Reference Bernardi and Boertien2017a); this was in part because the effects of nonintact families are actually more negative for those with higher socioeconomic status, even though the likelihood of experiencing a nonintact family is much more common for those with lower socioeconomic status. A recent working paper by Musick and Michelmore (Reference Musick and Michelmore2016) suggests that the higher proportion of unions that break up in the United States and the greater socioeconomic gradient in such compared to European countries is due to the higher prevalence of – and correlation among – behaviors linked to union instability (such as early childbearing and multipartnered fertility – which are also linked with unplanned pregnancies); this, in turn, points to greater inequality in what children get from parents in the United States compared to Western Europe.

Conclusion and Implications

This chapter summarizes what we know about recent patterns of family change and socioeconomic inequality therein across the United States and Europe. This is an important topic because family circumstances and transitions can influence individual well-being, happiness, identity, and relationships – and also play an important role in promoting or sustaining economic well-being. To the extent that family behaviors diverge by socioeconomic status within countries, this can reflect a broader pattern of accumulating advantage or disadvantage (depending on the direction of the gradient), with long-term ramifications for individuals and society; differences in outcomes for a given generation may then perpetuate growing inequality for the next generation.

Overall, in contrast to the United States, where there are consistent socioeconomic gradients in family behaviors – with more educated individuals experiencing more “traditional” and stable family patterns – there is much greater variability in Europe. Observed variation in family patterns by socioeconomic status (SES) seems to depend on numerous factors in particular places, including gender role attitudes and other cultural attributes, as well as social policies that facilitate balancing work and family and that reduce income inequality. At the same time, there is some evidence that family instability may be rising, especially for children from the least-educated families.

Also, it is important to consider how the timing of family changes may be related to the educational gradient. Conceptual arguments about the “second demographic transition” (Lesthaeghe Reference Lesthaeghe, Mason and Jensen1995, Reference Lesthaeghe2010) suggested that the highly educated would be in the vanguard of ushering in new family patterns; thus, there would initially be a positive educational gradient in “modern” family behaviors (such as delayed marriage and childbearing, and rising cohabitation, nonmarital childbearing, and divorce), but that this gradient would dissipate as the new ideas spread to lower socioeconomic strata. Here too, a consistent pattern cannot be observed across contexts, or particular behaviors, and more research over time (that allows comparisons by education across cohorts) is warranted.

Ultimately, it seems impossible to draw strong general conclusions about patterns of inequality in family behaviors – and the relationship to broader economic inequality – across Europe and the United States writ large. Instead, it appears that individual countries experience quite distinct patterns. As Perelli-Harris and Lyons-Amos observed in their recent study of partnership patterns (Reference Perelli-Harris and Lyons-Amos2016, p. 275), “macro-level country context explains more of the variance in predicted probabilities than individual-level education.” Thus, we are reminded of the importance of historical, cultural, social, and economic processes within particular geographic contexts and communities as key factors that influence human behavior and outcomes.

Introduction

Latin America is the most unequal continent in the world. According to World Bank data, the richest 10% accumulate more than 40% of the wealth. Latin American inequality has historical roots and has been exacerbated in recent times after decades of neoliberal reforms that neither generated sustained economic growth nor bridged the gap between the very few rich and the very large number of poor. Inequality affects Latin America in many ways (e.g., health, education) and family life is no exception (World Bank 2003). A pattern of social disadvantage emerges in every category of family formation: The evidence shows that early union formation and childbearing, cohabitation, single motherhood, and union dissolution are more common among women with low education than among those with higher education (secondary and beyond completed). Although this pattern holds true across Latin America, the effects of educational and income inequality interact in numerous ways, varying considerably from context to context.

Geohistorical legacies are of paramount importance in understanding family diversity in Latin America. At the individual level, ethnicity and religion frequently interact with themselves and with education, adding endless variations to the relationship between social status and family behavior. For instance, two individuals with similar profiles regarding education, ethnicity, and religion may show quite different family behavior depending on the region where they live, proving that “individuals have histories but regions have much longer histories” (Esteve and Lesthaeghe, Reference Esteve and Lesthaeghe2016, p. 269). This conclusion was originally drawn from cohabitation analysis but, as we will show in this chapter, it can be generalized to other family dimensions as well. To sum up, this underscores the importance of context in the analysis of families in Latin America.

In addition to geohistorical legacies, the historical presence in Latin America of family forms that are considered a recent phenomenon by Western standards (i.e., cohabitation, union instability, and single motherhood not connected to widowhood) complicates, from a theoretical perspective, any attempt to apply Western theoretical frameworks to Latin America, in particular the male breadwinner model (Becker Reference Becker1973), the second demographic transition (Lesthaeghe Reference Lesthaeghe, Mason and Jensen1995), diverging destinies (McLanahan Reference McLanahan2004), patterns of disadvantage (Perelli-Harris et al. Reference Perelli-Harris, Kreyenfeld and Kubisch2010), and the two halves of the gender revolution (Goldscheider, Bernhardt, and Lappegård Reference Goldscheider, Bernhardt and Lappegård2015). Elements of all these theories can be glimpsed. Fertility has declined rapidly across the region, sinking below replacement levels in a growing number of countries (CELADE 2013). Unmarried cohabitation has soared and marriage rates have plummeted at the same pace (Esteve, Lesthaeghe, and López-Gay Reference Esteve, Lesthaeghe and López-Gay2012). More children have been born out of wedlock (Laplante et al. Reference Laplante, Castro-Martín, Cortina and Martín-García2015), unions have become more unstable, and more households are now headed by women (Liu, Esteve, and Treviño Reference Liu, Esteve and Treviño2016). However, closer scrutiny of family trends reveals some differences from Western experience. Age at union formation and childbearing has barely changed (Esteve and Florez-Paredes Reference Esteve and Florez-Paredes2014). Household sizes have diminished but retained similar levels of internal complexity (Arriagada Reference Arriagada2004). Furthermore, trends over time and variations across regions reveal a significant paradox: A lack of correlation between micro- and macro dimensions of family behavior and change.

Within this context, this chapter summarizes trends in family life in Latin America over the last four decades, analyzing the rich collection of census and survey microdata available in the region and the literature on family dynamics. The chapter is organized into four main sections: Dimensions, trends in independent family indicators, divergence by education, and paradoxes. In the dimensions section, we describe family regimes in Latin America across four factors/dimensions and show their variation across 368 regions and 15 countries. In the trends section, we document changes over time since the 1970s with reference to the key variables contributing to each of the four factors. For a selection of countries – Mexico, Colombia, and Brazil– we explore in the third section divergence by education in women’s partnership status, extended co-residence, and household headship. And finally, in the paradoxes section, we analyze the lack of correlation between the micro- and macro dimensions of family change over time and across space. In short, this chapter provides a systematic characterization of family regimes in Latin America, trends in key indicators, divergence by educational status, and paradoxes of Latin American family change.

Dimensions

The concept of a family system has been widely used to refer to the set of characteristics defining the structure and functioning of families in a society (Laslett Reference Laslett1970; Reher Reference Reher1998). By definition, family systems have multiple dimensions, among them, when and who to marry, intergenerational transmission of property, filial obligations toward parents, and a long et cetera (Fauve-Chamoux Reference Fauve-Chamoux1984). Most research so far has been devoted to Europe and its internal diversity (e.g., Hajnal Reference Hajnal, Glass and Eversley1965), and Asia. Research on family systems in Latin America is rather scarce, scattered, and focused on specific subpopulations. Systematic study of the regional scale of the main dimensions of family change and its geographic boundaries is lacking (see exceptions in Arriagada Reference Irma2009; De Vos Reference De Vos1987; Quilodran Reference Quilodran1999). Recent availability of census microdata, through the Integrated Public Use of Microdata Series (IPUMS) international project, offers an opportunity for a partial yet broad description of variations in family life across Latin America. Obviously, there are many features of family systems that are well beyond what a census can measure, but there are others for which censuses can provide reasonable approximations (e.g., marriage timing, type of union, household composition, and female headship).

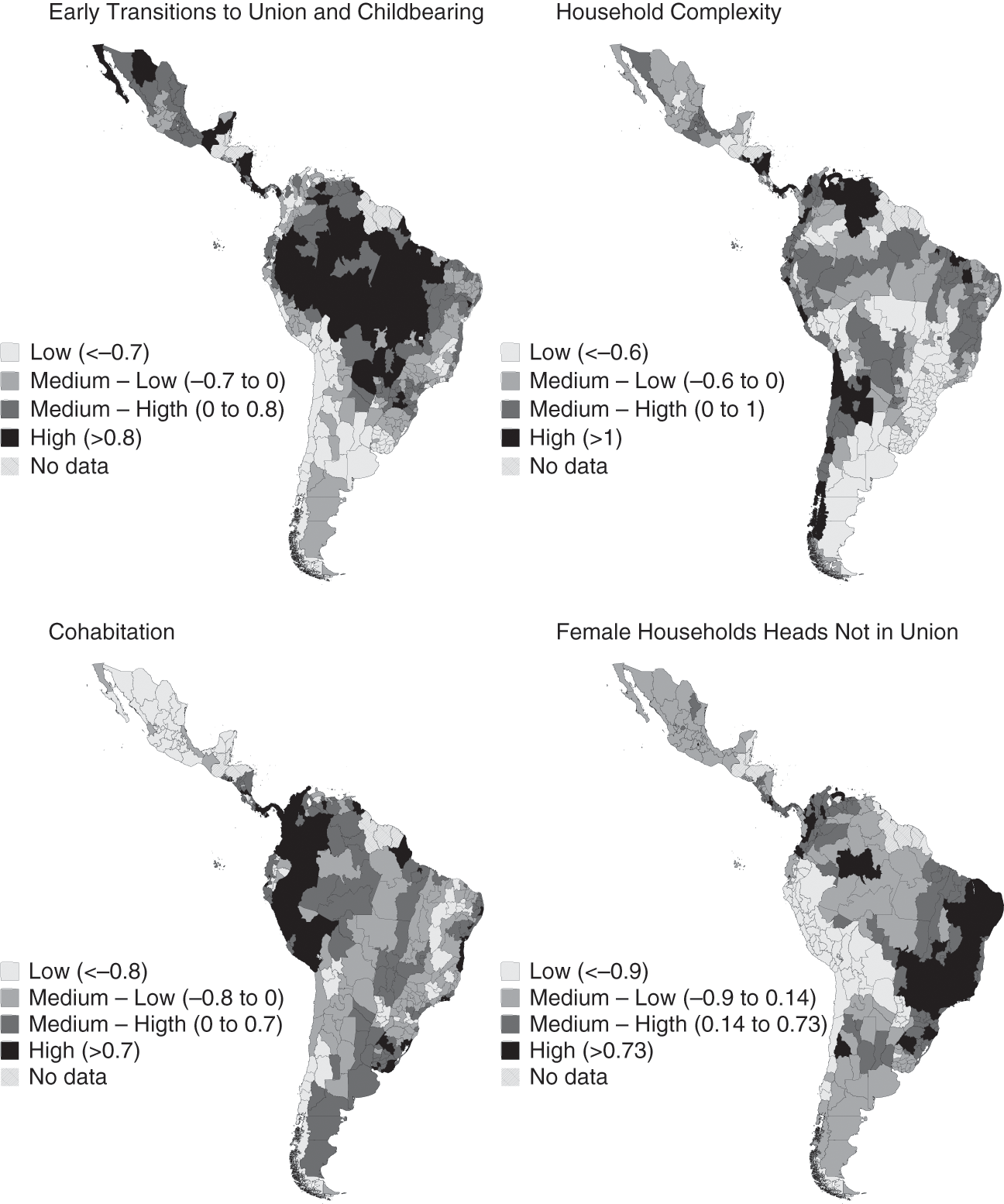

Hence, in this section we ask which main dimensions characterize family regimes in Latin America. We aim to identify independent dimensions of family life and trace their respective geographies using subnational-level data to account for within-country differences. We use factor analysis to identify the main dimensions emerging from 18 family life indicators calculated for 368 regions spread through 15 Latin America countries. Data come from IPUMS census microdata (Minnesota Population Center 2015). The chosen indicators are percentages of women at various ages regarding their situation with respect to marriage, cohabitation, childbearing, union dissolution, household headship, and living arrangements. In Appendix 2A.1, we show the list of the eighteen indicators for 2000 and their contribution (in technical terms, factor loads) to each dimension. The same analysis was carried out using data from the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s census rounds. The dimensions emerging from all these rounds were virtually the same, which demonstrates their stability over time. Hence, we only present results from the 2000 round.

One of the advantages of factor analysis is that it identifies groups of indicators that are independent of each other. Mere identification of such groupings is, per se, a very relevant result, because it allows characterization of family regimes on an empirical basis. Little is known about the dimensions that structure families in Latin America, and even less about the degree of independence among them.

First dimension: Union and Childbearing Calendars

The analysis yielded four factors or dimensions. The first dimension, union and childbearing calendars, refers to the age at which transitions to first union and first child occur. This factor mainly captures timing dimensions of fertility initiation and union formation, but it also includes two other variables, namely the proportion of women in unions at ages 15–44 and the proportion women both single and childless women in the age range of 15–19. The timing of union formation is closely correlated with the timing of childbearing, as, for most women, the two transitions occur within a relatively short period of time. Early transitions are associated with high intensity of union formation and childbearing. This dimension distinguishes between regions where men and women form unions and have children early in life and those where unions and children come later. Regarding internal differences, Map 1 in Figure 2.1 shows the factor scores for each region. Lighter colors indicate late transitions to union formation and childbearing and darker ones the opposite. At one end, Uruguayan, Chilean, and Argentinian (Southern Cone) women experience these transitions later than in any other regions in Latin America. At the opposite end, are women from Central America (e.g., Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Panama, and Mexico). Between these two poles, there are countries with sizeable internal variations. Brazilian women in the Amazon and in the northern states show dramatic differences from those in the southern states, where there has been much recent European immigration. Even in comparatively smaller countries like Bolivia, internal variations are huge. The Andean states (Colombia, Venezuela, Peru, and Bolivia) show the largest internal variations, as they combine areas with extremely diverse ethnic, religious, and economic backgrounds.

Figure 2.1 Maps of four dimensions that characterize families in Latin America, 2000

Caption for top left map: Early transitions to union and childbearing

Caption for top right map: Household complexity

Caption for bottom left map: Cohabitation

Caption for bottom right map: Female household heads not in union

Second Dimension: Household Complexity

The second dimension captures household complexity. All the original indicators (see Appendix 2A.1) measuring the complexity of living arrangements contribute to this (e.g., percentage of extended households, of children aged 0–4 in nuclear households, and of children aged 0–4 not related to the household head, among others). Positive values (darker colors in Map 2 of Figure 2.1) indicate complex household structures, which basically mean a high proportion of members and young children not directly related to the household head. Nicaragua, Venezuela, Panama, and El Salvador present the highest levels of household complexity. At the opposite extreme, Uruguay and Argentina show the lowest levels of household complexity. Showing some independence across dimensions, Chile breaks with its concurrence with Uruguay and Argentina in terms of late marriage while still revealing relatively high levels of household complexity. Costa Rica, in contrast, shows relatively early transitions to union formation and childbearing but low levels of household complexity.

Third Dimension: Married and Unmarried Cohabitation

The third dimension refers to the type of union. It distinguishes between married and unmarried cohabitation. In Map 3 of Figure 2.1, we show the factor scores for the third dimension emerging from the analysis. This dimension is constructed from all the indicators measuring the marital or nonmarital status of unions. Positive values (darker colors) indicate high levels of cohabitation, and negative values (lighter colors) the opposite. The geography of high levels of cohabitation has a distinctive profile: The highest levels of cohabitation appear in the non-Andean regions of the Andean countries (Colombia, Venezuela, Peru, and Ecuador) followed by Uruguay and Central America. Lower levels of cohabitation, hence higher marriage levels, are found in Ecuador (with some internal differences), Mexico, Chile, and Paraguay. The patterns of marriage and cohabitation basically mirror the path of history. Contrary to many Western societies, cohabitation coexisted with marriage since colonial times as a form of organizing unions among those who did not have access to the institution of marriage for many reasons. The implementation of European marriage in Latin America was uneven across regions and across population strata, as is reflected in Map 3.

Fourth Dimension: Nature of Female Household Headship

Finally, the fourth dimension, female household headship, consists of indicators regarding the type of female household heads rather than their numbers. It distinguishes between female household heads not in union (presumably raising children without the support of fathers) and female heads in union. Positive values (darker colors) indicate the presence of female-headed households in which women are not in union, whereas negative values and lighter colors indicate female household headship among women in union. Female household heads in Brazil, Costa Rica, Panama, and Colombia show the largest proportion of women not in a union and with children, compared to the much lower trend in Bolivia, Paraguay, and Peru. The latter countries have lower proportions of women not in union and with children than the former.

Trends in Independent Family Indicators

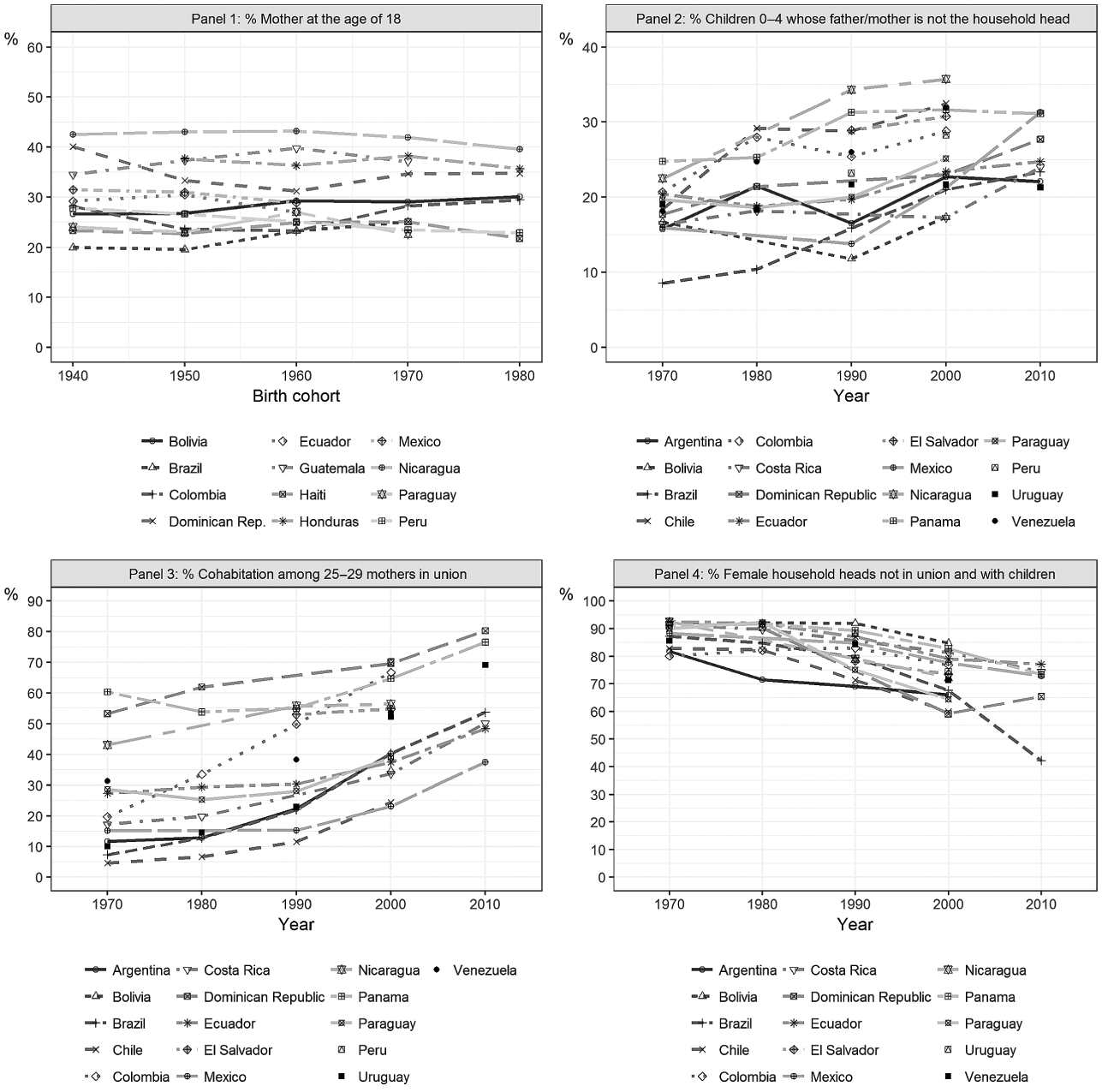

As noted above, the main (census-observable) dimensions that define family regimes in Latin America have remained relatively stable between 1970 and 2010. Nevertheless, many of the indicators contributing to these dimensions have changed dramatically over time. We now summarize the major trends in a selection of key variables representing each dimension. Figure 2.2 provides graphic representation of the trends in four separate panels.

Figure 2.2 Trends in selected key family life indicators in Latin America over recent decades and cohorts

Caption for Panel 1: % mothers at the age of 18

Caption for Panel 2: % children aged 0–4 whose father/mother is not the household head

Caption for Panel 3: % cohabitation among 25–29-year-old mothers in union

Caption for Panel 4: % female household heads not in union and with children

Age at First Child

Panel 1 of Figure 2.2, using all the available Demographic and Health Survey data in Latin America, shows the percentage of women by birth cohort who were mothers by the age of 18 in twelve Latin American countries. The timing of first childbearing has remained relatively stable over time, as has the percentage of women in a union at the age of 18 (results not shown). This suggests that trends in union formation and childbearing are strongly correlated. At later ages (e.g., 20 or 22), trends are equally stable. Such stability has been corroborated by many authors and is one of the salient characteristics of recent trends in family formation in Latin America, and sets Latin America apart from other regions where childbearing and union formation are increasingly postponed (Fussell and Palloni Reference Fussell and Palloni2004; Heaton and Forste Reference Heaton and Forste1998; Martin and Juárez Reference Martín and Juárez1995). This has occurred amidst marked declines in fertility, increased access to contraception, even at early ages, and substantial improvements in education and female labor force participation. Signs of postponement are still modest and reduced to a small number of countries and mainly among higher educated groups (Binstock Reference Binstock2010; Cabella and Pardo Reference Cabella, Pardo, Cavenaghi and Cabella2014; Guzmán et al. Reference Guzmán, Rodríguez, Martínez, Contreras and González2006; Rosero Bixby, Martin, and Martín-García Reference Rosero Bixby, Martín and Martín-García2009).

Extended Households

Regarding household complexity, in Panel 2 of Figure 2.2, we represent the percentage of children aged 0–4 whose father/mother is not the household head. On average, one in every four children is not the son or daughter of the household head. They may be living with other relatives, including grandparents, uncles, aunts, or nonrelatives. The percentage of children in these households ranges from 8.5% in Brazil in 1970 to 35.7% in Nicaragua in 2000, but for the vast majority of countries, values are within the 15% to 30% range. On average, these percentages have increased by 8% points between 1970 and 2010.

This indicator is highly correlated with the percentage of extended households. Both indicators contribute positively to the factor on household complexity (see Appendix 2A.1). The percentage of extended households ranges, for the majority of countries, within the 20% to 30% range, and has remained constant over time (results not shown). This shows that household complexity is quite widespread in Latin America, in particular Central America. However, comparison to the meaning and function of extended households differs from that which has been described for parts of Europe (Fauve-Chamoux and Ochiai Reference Fauve-Chamoux and Ochiai2009). Extended households in Latin America are not seeking to secure exploitation of land and transference of property but, rather, to cope with social vulnerability and provide a refuge for family members in insecure situations (Goldani and Verdugo Reference Goldani and Lazo2004). Few extended households in the region include two adult couples; most are comprised of a couple co-residing with other relatives (not in a union). These results reflect a very fluid system of living arrangements, in which preexisting nuclear households incorporate other relatives in need of housing (De Vos Reference De Vos1987). Latin America presents strong families concerned with coping with poverty, vulnerability, and uncertainty rather than with protecting family assets. For example, close to 70% of single mothers reside with their parents, and this high level has remained stable over the last three or four decades (Esteve, García-Román, and Lesthaeghe Reference Esteve, García-Román and Lesthaeghe2012).

Cohabitation

Panel 3 of Figure 2.2 shows the percentage of unions that are cohabiting but not married among mothers aged between 25 and 29, by census round and country. Among these young mothers, cohabitation is increasingly the context for childbearing. The percentage of cohabiting mothers has multiplied since the 1970s by three times or more in a number of countries, including Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, and Uruguay. Based on the latest figures available, childbearing within is more frequent than outside cohabitation in ten out of the sixteen countries represented in Panel 3.

Of all dimensions considered in this analysis, cohabitation is the one that is changing fastest. Marriage rates have dropped across Latin America. The decline of marriage has been completely offset by the rise of cohabitation. Hence, age at union formation has barely changed. The rise of cohabitation cannot be attributed to a single factor. Some authors suggest a partial fit to the theory of the second demographic transition (Esteve and Lesthaeghe Reference Esteve and Lesthaeghe2016), whereas others emphasize a continuation of the historical pattern of disadvantage (Rodriguez Vignoli Reference Rodríguez Vignoli2005). Analysis of World Values Survey for Latin America shows a major transformation of values toward post-materialist values consistent with the second demographic transition, including greater acceptance of homosexuality, euthanasia, and abortion, especially among the better-educated respondents (Esteve, García-Román, and Lesthaeghe Reference Esteve, García-Román and Lesthaeghe2012). However, the absence of postponement in union formation and childbearing does not fit with second demographic transition theory, and neither does the fact that a large part of early cohabitation takes place in complex and extended households (Esteve, García-Román, and Lesthaeghe Reference Esteve, García-Román and Lesthaeghe2012).

A combination of factors would therefore seem to be the most plausible explanation. Women with high levels of education are not only choosing cohabiting unions over marital unions more often but they are also postponing union formation and childbearing, whereas the least-educated women are choosing cohabitation more but without postponement. Recent research suggests the presence of (at least) three types of cohabitation: Traditional, blended, and innovative. Each type has its specific traits with regard to age at union formation, education, number of children, and stability (Covre-Sussai et al. Reference Covre-Sussai, Meuleman, Botterman and Matthijs2015). Traditional cohabitation is defined by early union formation and childbearing and is more frequent among women with low levels of education. At the opposite end, innovative cohabitation is associated with later union formation and a higher level of education. In between the traditional and the innovative cohabitation, the blended cohabitation has features of both types (e.g., early pregnancy and a higher level of education). Future research should inquire further into the different meanings of cohabitation and their implications for union stability and consequences for children.

Female-Headed Households

Finally, female headship has increased dramatically since the 1970s (Liu, Esteve, and Treviño Reference Liu, Esteve and Treviño2016), but still the vast majority of female household heads are women not in a union and with children. Panel 4 of Figure 2.2 shows the percentage of female heads between the ages of 35 and 44 who were mothers but were not in a union at the time of the census, either because they were single mothers or because they were separated, divorced, or widowed. In the 1970s, more than 80% of female heads across all countries fell into this category. These high figures remained relatively stable until the 1990s. The rise of headship rates among married and cohabiting women or among single women (without children) has slightly changed the profile of female heads. By the 2000s, the proportion of female heads with children and not in a union had decreased by 16% points on average. The rise in female headship among women in union is mainly due to an increasing propensity among women to report as household heads, even in the presence of their spouses (Liu, Esteve, and Treviño Reference Liu, Esteve and Treviño2016). Census forms have also reflected (and perhaps induced) this change, as they adopt more gender-neutral definitions of household headship.

Despite recent trends, the historically high levels of female-headed households in Latin America continue to be associated with the notable presence of single mothers resulting from short-lived unions due to union dissolution. Although families provide “shelter” to single mothers, many are on their own. Female-headed households have been associated with the feminization of poverty (Arias and Palloni Reference Arias and Palloni1999; Buvinic and Gupta Reference Buvinić and Gupta1997), but recent research has challenged the supposed relationship between female headship and poverty (Chant Reference 291Chant2003; Liu, Esteve, and Treviño Reference Liu, Esteve and Treviño2016; Medeiros and Costa Reference Medeiros and Costa2008), showing that the living conditions of female-headed households are not necessarily worse than in those headed by males (Chant Reference 291Chant2003, Chant Reference Chant2007; Medeiros and Costa Reference Medeiros and Costa2008; Moser Reference Moser and Chant2010; Quisumbing, Haddid, and Peña Reference Quisumbing, Haddad and Peña2001), and also that female-headed households are extremely diverse.

Divergence by Education in Women’s Timing and Context of Childbearing, Household Complexity, and Household Headship

Most of the indicators and trends described here show a steep educational gradient. Education is one of the most significant stratifying dimensions of social and demographic behavior, and Latin America is no exception. There is ample evidence that, in Latin America, education is a strong predictor for the age at which union formation and childbearing occur, as well as whether unions are marital or not. Furthermore, access to education is constrained by social class. Despite major progress in universalizing access to primary and secondary education, schools continue to reproduce inequality (OECD 2013a).

Here we investigate whether family inequality is increasing over time. We explore divergence by education in the four family dimensions identified in the dimensions section: Timing at union formation and childbearing; household complexity; cohabitation vs. marriage; and nature of female household headship. We present results only for Colombia, Brazil, and Mexico, which are three of the largest and most populated countries in Latin America.

Timing and Context of Childbearing

The first and third dimensions are analyzed together in Figure 2.3 (see exact figures in Appendix 2A.2A). Three-dimensional histograms with stacked bars represent, on the z-axis, the percentage of mothers among women aged between 25 and 29. Among mothers, we distinguish between married, cohabiting, or single (not in a union). On the x-axis, we represent change over time, showing data from various census rounds. On the y-axis, women are classified according to their level of education: Primary or lower; secondary completed; and university.

Figure 2.3 Percentage of mothers among women aged from 25 to 29 by union status, educational attainment, and census round

Caption for top: Mexico

Caption for middle: Colombia

Caption for bottom: Brazil

Despite being three different countries, the patterns and trends in Mexico, Brazil, and Colombia are quite similar. First, the percentage of women who are mothers is highest among those with primary or lower education, intermediate among women with only secondary education, and motherhood is least common at ages 25–29 among women with a university education. This indicates that highly educated women have children, if any, at later ages when compared with women of lower levels of education.

Second, the proportion of women who have become mothers by 25–29 years old have been almost stable among the first two groups (primary and secondary education), while over time, fertility postponement appears among women with a higher education. As shown in Figure 2.3, the percentage of highly educated women who are mothers has decreased, but the percentage for the other two groups has remained constant. Trends are diverging across educational groups. In Mexico, the percentage of women with a university education who are mothers has decreased from 47.1% in 1970 to 32.8% in 2010 and, in Brazil, from 40.3% to 23.9% between 1980 and 2010.

The most important transformation is the change in the partnership context of childrearing. This is most noticeable among women with secondary education or lower. For these two groups, the percentage of women who are mothers is stable, but the proportion of those rearing children within marriage is decreasing. Childbearing and child-rearing are increasingly taking place within the context of cohabitation and single motherhood. Trends unanimously point in this direction but the pace of change varies from country to country. Mexico has the highest proportion of mothers who are married mothers. It is still above 50% in all educational groups in 2010. In Colombia in 2005, married mothers represent less than 45% in all educational groups, dropping to 19% among the lower educated groups. Married mothers represent less than 50% in Brazil in 2010, except for those with a university education (58%). Mothers who are in cohabiting unions comprise a growing proportion of all mothers in all educational groups. The share of lone mothers, residual in the 1980s, now represent at least 15% of mothers in Mexico and 20% in Colombia and Brazil. Marriage predominates among highly educated women, but even among the highly educated, cohabitation and lone motherhood are becoming more common contexts for child-rearing. However, women with high levels of education are postponing childbearing and, accordingly, the trends in the partnership context of child-rearing are likely to be driven by selection effects.

In any case, the trends depicted so far show a clear educational gradient regarding age at childbearing and diverging trends with respect to change over time. Moreover, there is also a dramatic transformation of the family context of childbearing as marriage rates are plummeting and cohabitation and single motherhood are rising rapidly as well.

Household Complexity

Using three-dimensional stacked bar graphs, in Figure 2.4, we represent the percentage of women between the ages of 25 and 29 who reside in an extended household by year and educational attainment (see exact figures in Appendix 2A.2B). Additionally, we distinguish between mothers and non-mothers. Extended co-residence among young women has risen over time in the three countries and educational groups, except for Colombian women with primary or lower education. Mexico has experienced by far the largest increase in extended co-residence. Trends are similar across all educational groups, but the distribution between mothers and non-mothers is quite distinct, most probably because of higher educated women having children later. Half or more of women with primary and secondary education who live in extended households are mothers. Among women with a university education, this figure is lower than 50%, with the only exception of Colombia in 1993. In any case, and according to the most recent data, around one in three women in Mexico and one in four women in Colombia and Brazil reside in an extended household. In Mexico and Brazil, higher educated women are less likely to be in extended households, but in Colombia, the opposite pattern holds true. However, the gap between the higher and the lower educated group is no bigger than 5% points. This indicates that extended co-residence is quite widespread across all educational groups.

Figure 2.4 Percentage of women aged from 25 to 29 who reside in an extended household by motherhood status, educational attainment, and census round

Caption for top: Mexico

Caption for middle: Colombia

Caption for bottom: Brazil

Household Headship