Introduction

As the population ages, the number of people with dementia will increase significantly (Prince et al., Reference Prince, Wimo, Guerchet, Ali, Wu and Prina2015). This increase brings urgency to researching, designing and delivering care and supports for people with dementia which improve their wellbeing and quality of life. Historically, the personhood of people with dementia was deemed to have been undermined or completely lost by the onset of the disease (Small et al., Reference Small, Geldart, Gutman and Clarke Scott1998; Surr, Reference Surr2006). The belief that people with dementia lose personhood evolved from Cartesian definitions, which defined the latter as requiring cognition (Dewing, Reference Dewing2008). While the narrative around people with dementia has changed for the better in the last 30 years, in some cases, the belief that people with dementia lack personhood persists, despite evidence to the contrary (Caddell and Clare, Reference Caddell and Clare2010; Hunter et al., Reference Hunter, Hadjistavropoulos, Smythe, Malloy, Kaasalainen and Williams2013). The denial of personhood has important implications for the autonomy, agency and wellbeing of people with dementia.

The modern study of personhood in dementia can be traced to Kitwood and Bredin's (Reference Kitwood and Bredin1992) work which explored the significance of supporting personhood in dementia. Kitwood later redefined personhood as ‘a standing or status that is bestowed upon one human being, by others, in the context of relationship and social being’ (Kitwood, Reference Kitwood1997: 8), making it relational and placing it in the domain of roles, relationships and social interaction (Tolhurst et al., Reference Tolhurst, Bhattacharyya and Kingston2014). Related work by Sabat and Harré (Reference Sabat and Harré1992), on the perceived loss of self in people with dementia, suggests that some losses arise from how others view and treat the person with dementia. Other commentators have expanded the definition of personhood in dementia to include additional social and relational dimensions, e.g. Buron (Reference Buron2008) defines personhood in dementia on three levels: biologic, individual and sociologic. O'Connor et al. (Reference O'Connor, Phinney, Smith, Small, Purves, Perry, Drance, Donnelly, Chaudhury and Beattie2007) posit that research into personhood should focus on three areas: the subjective experience of the person with dementia, the interactional environment of the person with dementia and the wider socio-cultural context. Some authors argue that personhood in dementia is framed solely, or excessively, as relational, ignoring embodied elements of selfhood (Kontos, Reference Kontos2005; Baldwin et al., Reference Baldwin, Capstick, Phinney, Purves, O'Connor, Chaudhury, Bartlett, Baldwin and Capstick2007). Kontos and Martin (Reference Kontos and Martin2013) point to how the examination of embodied selfhood has enhanced the research landscape on selfhood and memory in dementia. This includes, for example, ethnographical research on modern art and personhood (Selberg, Reference Selberg2015), and the exploration of other concepts such as relational embodiment and intercorporeality (Jenkins, Reference Jenkins2014; Zeiler, Reference Zeiler2014; Bryden, Reference Bryden2018). It is also important to point to how the concept of personhood itself varies with place and time. The concept may take on different forms, meanings or practices in other cultural settings which have different ideas of what it means to be an individual or, indeed, part of a group or community (De Craemer, Reference De Craemer1983). There is some examination of this already in existing research on dementia which discuss notions such as couplehood (Hellström et al., Reference Hellström, Nolan and Lundh2005) and collective social identity (Beard and Fox, Reference Beard and Fox2008; Robbins, Reference Robbins2019). Bryden (Reference Bryden2018), reflecting on her own lived experience of dementia, proposes three aspects of the self: the embodied self, the relational self and the narrative self. Overall, there is significant theoretical ambiguity around personhood, partly explained by its conflation with other related concepts. Self-identity and the self are sometimes treated as synonymous to personhood and at other times differentiated from it (Higgs and Gilleard, Reference Higgs and Gilleard2016). Moreover, terms such as autonomy, dignity, respect and agency are frequently conceptualised as both elements of personhood and mechanisms through which it can be supported.

For all its ambiguity, personhood is recognised as a key driver of person-centred care in dementia (Brooker, Reference Brooker2007; Fazio et al., Reference Fazio, Pace, Flinner and Kallmyer2018), and supporting personhood through providing person-centred care continues to be a key policy objective in many countries (see e.g. Welsh Government, 2018; Public Health Agency of Canada, 2019). That said, there has been little empirical research on personhood in relation to care provision in dementia and what does exist is often criticised for lacking clear theoretical foundations (Caddell and Clare, Reference Caddell and Clare2010, Reference Caddell and Clare2012). There is limited knowledge on the experience of personhood in dementia from the perspective of people with dementia (Nowell et al., Reference Nowell, Thornton and Simpson2013), and in particular little research into personhood in dementia using a multiple perspective study design. There has also been little examination of what family carers and formal carers think about personhood in dementia, particularly in relation to its effect on care delivery. One study found that nihilistic beliefs about personhood amongst formal carers had a negative impact on care practices (Hunter et al., Reference Hunter, Hadjistavropoulos, Smythe, Malloy, Kaasalainen and Williams2013). In spite of the absence of empirical evidence, or maybe because of it, the Irish National Dementia Strategy (Department of Health, 2014) identifies personhood as one of its two core principles (the other being citizenship), reflecting a wider public appetite for supporting personhood through person-centred models (The Institute of Public Health in Ireland, 2018). However, the realisation of the concept and its influence on the practice of care remains unproven. For example, the provision of person-centred care in Irish nursing homes is questionable (Colomer and de Vries, Reference Colomer and de Vries2016), as is the degree to which personhood or person-centred outcomes are currently measured, or indeed valued, by regulators and policy makers (Meagher and Conroy, Reference Meagher and Conroy2015). Ultimately, there is evidence of ambiguity and a lack of understanding around personhood and person-centred care in dementia in Ireland, and how to actualise these concepts in day-to-day care relationships (Hennelly and O'Shea, Reference Hennelly and O'Shea2019).

The objective of this paper is to explore the interpretation and application of personhood within formal care provision for people with dementia in Ireland. The analysis is not about the conceptualisation of personhood for its own sake, but is focused more on the practice implications of those conceptualisations for formal care provision in dementia. The study conceptualises personhood as being both relational and individual, meaning that it is socially constructed within relationships (Kitwood, Reference Kitwood1997) and includes the self of the person with dementia (Sabat and Harré, Reference Sabat and Harré1992). While the role of embodied selfhood (Kontos, Reference Kontos2005) in conceptualisations of personhood is acknowledged, this aspect of personhood is not examined in this study, which relies entirely on qualitative interviews with participants rather than ethnographic scholarship. The study examines the testimony of people with dementia, family carers and formal carers to generate an understanding of the current approach to personhood in dementia, both theoretically and practically, within formal care provision in Ireland.

Methods

Approach

This study uses a multiple perspective design incorporating interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA). A multiple perspective approach is often used in health-care research when examining the similarities and differences in the perceptions of different groups (Kendall et al., Reference Kendall, Murray, Carduff, Worth, Harris, Lloyd, Cavers, Grant, Boyd and Sheikh2009), and can be very informative in circumstances such as dementia care, where people with the disease may experience difficulty verbalising their perspectives (Larkin et al., Reference Larkin, Shaw and Flowers2019). IPA examines how people make sense of their experiences (Pietkiewicz and Smith, Reference Pietkiewicz and Smith2014), which involves exploring in detail the participant's view of the phenomenon being investigated (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Jarman, Osborn, Murray and Chamberlain1999). IPA is particularly suited to this research question due to its phenomenological base with its focus on the participants’ personal experiences and perceptions and its interpretative stance crucial to gaining an ‘insider's perspective’ on personhood in dementia (Conrad, as cited in Smith et al., Reference Smith, Jarman, Osborn, Murray and Chamberlain1999).

Sample selection

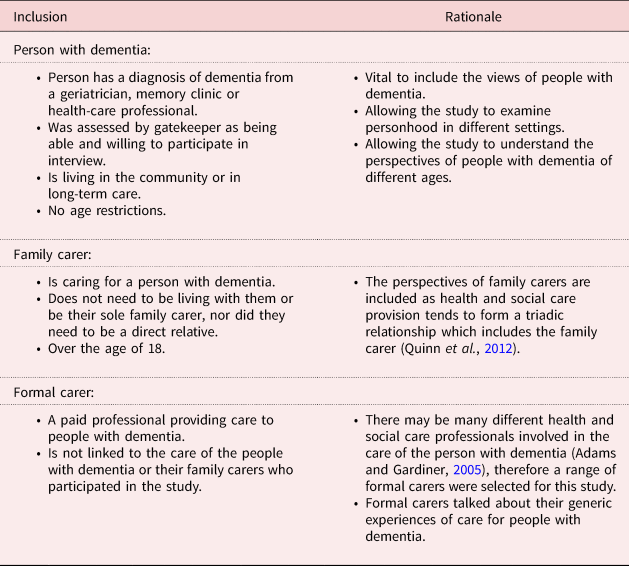

Participants for the study were recruited purposively (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Flowers and Larkin2009), through gatekeepers such as the Alzheimer Society of Ireland and the Health Service Executive in Ireland. Gatekeepers were asked to identify people with dementia and family carers who were both willing and able to respond to the formal interview process which potentially could include people at all stages of dementia. Formal carers were recruited mainly through snowball recruitment techniques, while remaining mindful to recruit formal carers from across the spectrum of formal care provision. The inclusion criteria for each participant group is included in Table 1.

Table 1. Inclusion criteria for study participants

In total, 31 people participated in this study, eight people with dementia, eight family carers and 15 formal carers, resulting in 30 interviews in total (one interview was conducted as a dyad). Of the participants with dementia, five are female and three male, ranging in age from 58 to 84. Of the family carers five are female and three male. Of the formal carers 11 are female and four male. Formal carers include a range of professions: nurses, psychiatric nurses, a psychologist, home care assistants, nursing home care assistants, a home care service manager, a general practitioner (GP) and a geriatrician. For anonymity reasons, including protecting the anonymity of the participants within a dyad, individual-level data are not reported for the participants with dementia or family carers (Ummel and Achille, Reference Ummel and Achille2016).

Research instruments

Semi-structured interviews were deemed to be the most appropriate method to gain an in-depth understanding of the three groups’ perspectives. A separate interview guide was designed for each group through reviewing existing research and advice on designing guides for IPA studies (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Flowers and Larkin2009). Interview questions focused on the participants’ conceptualisation of personhood and related concepts such as autonomy, flexibility, choice, relationships, communication, dignity and respect, particularly in the context of formal care provision. Participant information sheets were provided to all participants prior to the interviews. A second more accessible information sheet, as well as an accessible consent form were drafted, using the guidelines of the Dementia Engagement and Empowerment Project (2013), for participants with dementia and used as required. Pilot interviews were carried out with seven participants, three people with dementia, two family carers and two formal carers, to test the reliability and feasibility of the research instruments.

Data collection

The interviews were conducted in various settings including the Centre for Economic and Social Research on Dementia, participants’ own homes, their places of work and in long-term care settings, across Ireland, in both urban and rural locations. Interviews were mainly conducted on a one-to-one basis, interviewer and participant; the exceptions to that approach were for a small number of people with dementia who chose to be interviewed in the company of their family carer. The interviews were carried out by the first author, between January 2018 and January 2019. They were audio recorded, transcribed verbatim and anonymised. Several factors were considered when setting up the interviews to support communication, particularly among people with dementia. A key goal, prior to and at the start of the interview, was to develop a good rapport and relationship with the participant (Bartlett et al., Reference Bartlett, Milne and Croucher2019). During the interviews, the interviewer encouraged the expression of feeling through speaking with participants as equals, finding common ground, sharing a little of oneself as well as being attentive, using prompts and probes, being non-judgemental, allowing silence, and also being aware of body language and non-verbal cues (Tappen et al., Reference Tappen, Williams-Burgess, Edelstein, Touhy and Fishman1997; Denscombe, Reference Denscombe2014; Pietkiewicz and Smith, Reference Pietkiewicz and Smith2014). Where possible, the interviewer met with the participant in person or spoke over the phone initially to explain the study and then carried out interviews a week or two later. This allowed participants time to consider their participation. The interviewer took time to explain the research again at the start of the interview and the policy of ongoing assent was applied throughout. The interviews lasted between 30 minutes and two hours.

Statement of ethical approval

Ethical approval for this study was provided by the National University of Ireland Galway Research Ethics Committee (University Ethics Reference 18-Jan-06). For participants who could not provide consent, proxy consent was sought along with ongoing assent (Slaughter et al., Reference Slaughter, Cole, Jennings and Reimer2007). Distress and researcher safety protocols were adhered to in all interviews, including formal debrief with the second author following the interviews.

Data analysis

Guidelines from Smith et al. (Reference Smith, Flowers and Larkin2009) and Larkin et al. (Reference Larkin, Shaw and Flowers2019) in conducting IPA on large sample sizes were used. Firstly, the transcript was read and reread. Next, exploratory comments were noted, including descriptive, linguistic and conceptual comments (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Flowers and Larkin2009). From the exploratory comments more concise and abstract emergent themes were identified (Pietkiewicz and Smith, Reference Pietkiewicz and Smith2014). Once all of the transcripts for a particular group were analysed, the coded transcripts were re-examined, clustering the emergent themes for that group (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Jarman, Osborn, Murray and Chamberlain1999). When the three groups had been analysed separately, a merging of the three groups was conducted, what Larkin et al. (Reference Larkin, Shaw and Flowers2019) refer to as a mini meta-synthesis. This involved looking for consensus, conflict, reciprocity of concepts and paths of meaning across the data from the three groups (Larkin et al., Reference Larkin, Shaw and Flowers2019). Only those themes that were present in 50 per cent or more of the transcripts in a given group were synthesised (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Flowers and Larkin2009). Elements of the analysis were very much an iterative process, particularly at the write-up stage. The analysis was conducted by the first author with support from the second author at each stage. Yardley's four principles for assessing quality in IPA studies (as cited in Smith et al., Reference Smith, Flowers and Larkin2009) were applied to this study. The interviews were conducted in a manner which ensured there was adequate sensitivity to context. Reflective and observation notes taken prior and post-interview provided a source for data triangulation. To provide transparency in the analysis, a clear audit trail was recorded within NVivo (version 11 2015, QSR International, Melbourne), and in this paper direct participant quotes are used to illustrate each theme.

Findings

Participants provided rich and detailed accounts of personhood and how it can be supported in formal care in Ireland, making it difficult to distil all of the findings into a single paper. The findings are divided into three sections: core elements of personhood; barriers to supporting personhood in practice; and enhancing personhood in formal care provision.

The core elements of personhood

This theme examines how personhood is conceptualised across the three groups. All three groups define people with dementia as having interests, preferences and traits, lifecourse experience and being social. Some of the participants reference the significance of family and place to personhood.

All participants emphasise the importance of interests and preferences, and how they are part of personhood. Participants with dementia described themselves in many ways such as being active, being a good person and how they pursue different hobbies. Family carers also defined the person with dementia through their interests and personality traits. Ronan, a GP, reflects on how interests and passions form part of identity:

I mean everyone has a passion, no matter how small or odd it might be. And often that forms your identity. Running, stamp collecting, whatever it may be, but everyone has some passion.

Almost all of the participants reflect on lifecourse experiences, how they contribute to who a person is and what this means for personhood. Participants with dementia and family carers spoke about occupational roles and the impact of different people and events on their lives. The participants with dementia had fulfilled various roles across the lifecourse, including being a farmer, being a member of the army, working in the local community and working as home-makers. Thomas, a person with dementia, reflects on how hard he had worked during his life:

Thomas: So I worked hard in me day.

Interviewer: Emm, yea.

Thomas: I worked all over the country.

Almost all the participants conceptualise the person with dementia as a social being, one whose wellbeing depends on social interaction, meeting and engaging with others. This includes enjoying social activities, keeping up with local news, getting out and about, and a feeling of belonging. Cynthia, a family carer, describes how her mother enjoys being part of a group:

She was sitting down as quiet as anything, but she was part of a group … she was really content and she'd be joining in on jokes.

All participants with dementia, except one, reference the importance of family, defining themselves through their relationships to family members and at times friends. Participants with dementia referenced various familial roles, including being spouses, parents and siblings. For Maura, a participant with dementia and a mother, family is a hugely significant aspect of her life:

Well the family was very important to me like, very important to me in my life like was very important the family like.

Family could have both positive and negative impacts on the lives of participants with dementia. For Christine, a participant with dementia, family were also a source of tension or anxiety:

On good terms with the people that matter to me in my life within my family and my circle of friends and ah there's certain people I've had to kind of withdraw from in my life as well for health reasons.

Family carers spoke less about the meaning of family. However, they spoke in detail about their own relationship with the person with dementia and how this was impacted by dementia. They referred to a wide variety of different experiences in their relationships with the person with dementia from conflict to loving relationships. The issue of conflict is discussed in more detail under barriers to supporting personhood. Similarly, formal carers did not reflect as deeply on the meaning of family in the context of personhood but did refer to their relationships with family carers.

The majority of participants with dementia reference the importance of place. Of participants with dementia who referenced place, this included people living in both urban and rural locations, as well as people living in long-term care settings. The references to place included to the physical landscape as well as a sense of familiarity and belonging to place. Thomas, a participant with dementia, had lived in the same place all his life and defined his personhood through this:

Interviewer: Could you tell me a little about yourself about your life?

Thomas: Well sure I was reared, born and reared here [place name].

There was no reference to place from family carers and few references from formal carers. Barbara, a community nurse, refers to the connection between place and personhood, viewing it as part of the self:

I think sense of identity is about like, that thing about who you are, where you come from, maybe a bit about what you did, although I don't know in the future will that make much sense to us, what we did and that sense of belonging that you belong wherever you are, that you belong to somewhere.

Interpreting changes to personhood

While there is general consensus on expressions of personhood, there is less agreement on interpreting changes to personhood. Participants with dementia convey personhood through talking about who they are, being certain of the self, being aware of their memory problems and seeing themselves as ‘normal’, like everyone else. Nuala, a participant with dementia, sees herself as an ‘average’ person:

Yea I'm just an average person, an average person, I like things to be done properly and tastefully and am honestly.

There is no indication that any of the participants with dementia think they are less of a person or do not have personhood. However, a minority of participants with dementia refer to uncertainty around their future self, in particular, in relation to their future care needs. Christine talks about how she would like formal carers to get to know her now to be better equipped to support her in the future:

I think it's good for them to get to know me at this stage because I'm not things will change I'm sure am at least they kinda get to know me as I am now they'll be able to remember me as I will be (chuckle) then do you know what I mean.

There is significantly more ambiguity among family carers and formal carers in understanding and interpreting changes associated with dementia, and what this means for personhood. They see the person with dementia as both changed and unchanged. When the person is viewed as unchanged, this is presented in a positive light, implying that their personhood remains intact, that the person with dementia is ‘still there’. They refer to how it is important to accept the person with dementia as they are and have a normalised conceptualisation of that person. They acknowledge that everyone is different and that this uniqueness is at the core of every person, including people with dementia. Karen, a home care assistant, takes the person with dementia's perspective in relation to care practices, and as a consequence sees her own personhood reflected in the person with dementia:

Yea, so I just treat them like you'd like to be treated if it was yourself.

When the person with dementia is viewed as different or changed, family carers and formal carers often perceive them as lost, as being a problem, being in their own world, becoming child-like over time, not being the person they once were, being unstable, passive and changing. Michael, a family carer, caring for his mother, explains how little changes become big changes:

I know week on week I can see changes, little changes all the time and I know that little changes to me are big changes to people that haven't been here for a while.

For family carers and formal carers, there are essentially two strands to interpreting change: viewing the person with dementia as problematic or blaming the disease. Formal carers, in particular, view some people with dementia as creating and causing stress in the care environment due to their behaviour. In other instances, formal carers blame issues of change on dementia itself, explaining how they used this rationale to accept or come to terms with ‘problematic’ behaviour. The difficulties family carers and formal carers experience in interpreting changes to personhood is reflected in the barriers to supporting personhood identified in the next theme.

Barriers to supporting personhood in practice

This theme examines barriers to supporting the core elements of personhood within formal care provision. These are categorised into two different types of barriers: interpersonal and structural.

Interpersonal barriers

Interpersonal barriers are difficulties experienced in the formal care relationship due to the actions of individual members of the care triad. Two main difficulties are identified by participants, conflict and a lack of understanding of dementia. The majority of formal carers, and a minority of family carers and participants with dementia, identify conflict in the care relationship as a limiting factor to supporting personhood. Formal carers refer to how, at times, family is a barrier to supporting personhood and reflect on the need to have the family ‘on the same hymn sheet’. Conflict evolves from differences between what family and formal carers view as important in the care relationship. The majority of formal carers also refer to conflict in the relationship with the person with dementia. Ita, a home care assistant, illustrates the difficulty of dealing with agitated behaviour or abuse, including racism:

Some of them you kind of think, ah here now, I'm not here to do this you know. I don't get paid enough or this isn't my job to be sitting here and taking all this abuse, you know?

When discussing consistency in the care relationship, a minority of participants refer to how a change of personnel is desirable if there is tension or conflict.

A lack of understanding of dementia is also cited as an interpersonal barrier. Formal carers reference how families do not always understand dementia, which may lead to poor communication within households, making the formal carers’ job more difficult and the potential for conflict higher. Pauline, a home care assistant, reflects on the need for more education and training for family:

Families don't always understand what's, am, have more education, maybe, for families, as regards dementia … I have seen how families would get frustrated with the person.

Formal carers also reference a lack of training in their own profession as a barrier to supporting personhood. This is reflected in the accounts of family carers who experience significant difficulty getting a diagnosis, citing issues around not being taken seriously and ageist attitudes towards dementia. Louise, a family carer for her father, felt ‘fobbed off’ by her father's GP:

The GP he had attended all his life really fobbed us off … and the GP basically was saying, ‘sure he's 80 or 80 whatever and sure what do you expect’.

Structural barriers

Nearly all of the participants reference structural barriers to the development of personhood ideals. These are external factors which impact negatively on personhood and are related to how formal care provision is structured and delivered in Ireland. These include: issues around choice, flexibility, autonomy, consistency, time constraints and feeling obliged to accept care.

Participants with dementia and family carers have varied experiences of receiving choice in relation to care supports and services. They have mixed views of choice depending on their experience of it. For some, choice is very important, while others are more circumspect, conceptualising it as an impossibility in the current resource-constrained system and so, by consequence, something to which there is no point aspiring. Patrick, a participant with dementia, sees little point in having choice:

Patrick: No, there wasn't, never really, any choice given or

Interviewer: Ok. And would you like to have a choice?

Patrick: Sure ah it makes very little difference.

While family carers and participants with dementia view choice in relation to service provision, formal carers conceptualise choice in a more nuanced way, in relation to the care relationship, and emphasise the goal of personalised care delivery. The majority of formal carers conceptualise choice as limited; as a possibility rather than a certainty. Sometimes choice conflicts with risk to the person with dementia and other care recipients and therefore has to be restricted. Other times, the budget constraint does not allow any choice to be provided to the person with dementia. However, formal carers emphasise the significance of choice. Claire, a clinical psychologist, emphasises how it is important to provide choice to the person with dementia, even within limited choice sets:

I think it's extremely important where possible. And even where not possible, I think it's really important to find choices within the limited choices.

A concept which goes hand in hand with choice is flexibility. Fewer participants with dementia refer to flexibility, but those who do give examples of how they would benefit from flexibility in service provision. Family carers point to how the absence of flexibility means that the person with dementia misses out on services, which also impacts negatively on the family carer. However, before developing flexible services you have to address availability, which is sometimes limited and often non-existent. Louise, a family carer for her father, notes the irony in offering flexibility and choice, when there is none:

You get the form out and it says, you know, pick in order of preference what company you want for the hours and whatnot. And behind it all you just get whoever has hours available and that's it, there is no choice.

Coupled with choice and flexibility, the issue of consistency of care personnel is also discussed by participants. The majority of participants think consistency is important and key to providing good care. However, half of the family carers reference issues around inconsistency across formal carers and a minority of participants with dementia refer to how care is a ‘mixed bag’. Johnathon, a family carer for his aunt, outlines the impact of inconsistency on his loved one:

They were changing, there might be one girl [home care assistant] one day and a different girl another day and that threw her off altogether I think. If she got used to the one person I think it would have been way better.

Denying autonomy is also identified by some formal carers as a barrier to supporting personhood. They outline how it is important to respect autonomy, but how they have to balance a need for autonomy with risk to the person with dementia and other care recipients. Sometimes power imbalances in the care relationship may impact on autonomy. Nuala, a participant with dementia, describes the ‘reporting structure’ within a care setting she attends:

Interviewer: Do you think you're allowed to do things for yourself when you're down there?

Nuala: I wouldn't think so no no way … I'd be limited in what I could ask for…

Interviewer: So if you wanted to do something yea you wouldn't?

Nuala: Go to the head person whoever and get permission.

Time constraints are cited by nearly all of the formal carers and family carers as a barrier to supporting personhood. One family carer describes current formal care provision as being ‘hit and run’. Shane, a nursing home assistant, is frustrated at not having enough time to carry out his role:

I think the one thing that matters most is the that they probably never get enough of is just time and you know as much one-to-one you know relating as possible and … it's one of the more frustrating aspects of the job and it's just not possible.

The majority of family carers, and a minority of formal carers and participants with dementia, reference how care is sometimes forced on the person with dementia, resulting in a person receiving care that they may not want or need. Thomas, a participant with dementia, felt obliged to attend a day care setting:

Interviewer: Ok, so you go in a couple of days in the week?

Thomas: Yea yea but sure I have to for who or what (inaudible) anyway.

Interviewer: You have to sorry?

Thomas: Put up with what I'm at.

Enhancing personhood in formal care provision

This section identifies practices to enhance the core elements of personhood in formal care. The focus is on changes that participants identified as being central to any new model of care that has personhood at its core. These changes are grouped under two sub-headings: communication skills for personhood-enhancing care and traits of personhood-enhancing care.

Communication skills for personhood-enhancing care

Good communication skills are identified as important for personhood-enhancing care. However, there is no strong degree of consensus on what ‘good’ means. It is not the case that there is strong evidence of conflict among the three groups of respondents, but rather there is weak consensus, with participants in each group citing a wide range of requirements. However, all of the groups refer to the need for communication to be easy, clear and simple, citing the content and speed of delivery of the language used. Formal carers are more likely to focus in on specific aspects of effective communication, such as the need to be at the person's level, to sit with and maintain eye contact with the person, to take time and to listen.

For half of the family carers, and a minority of formal carers, humour and fun are important. Participants with dementia do not explicitly reference humour, however, they all engaged in jokes and laughter with the interviewer during the interview process, suggesting that it remains an important part of their own communication strategy and underlying personality. Harry, a nurse in a long-stay setting, enjoys humour with people to whom he provides care:

A resident, he used to take the piss out of me here, ‘Model them again for me, them jumpers. Which ones you want me to put on?’ He says ‘I don't give a shite what I put on. You know? (chuckle)’ … That's what I like, like a bit of banter with them, you get to build up your trust.

One theme, unique to and referenced by all of the formal carers, is the concept of finding balance in the care relationship. Formal carers use various communication skills to resolve conflict and difficult situations such as: avoiding upsetting the person with dementia, avoiding conflict and not taking things personally. They try to take a step back from a situation if it becomes tense and refer to ‘going with the person’, e.g. agreeing with the person with dementia if their current reality was not accurate. In this determination to find balance, the majority of formal carers talk about persuading the person with dementia to do certain things. Laura, who manages a home care service, describes the skills required to achieve this balance:

Calm and initiative and sometimes you just have to give a client space and come back to them then afterwards and try … You kind of have to go with the flow.

Finding balance is not solely limited to communication. Formal carers also try to balance all elements of care to suit the support required by the person with dementia, depending on the type and stage of dementia. This includes personalising care tasks and balancing activities to ensure that it is right for the individual. Formal carers refer to how care should, if at all possible, always be different as every person is different. However, half of the formal carers emphasise how generic care tends to override personalised care when time and resources are scarce. Claire, a clinical psychologist, reflects on how personhood and person-centred care is not always prioritised:

I think they often see the doing the activity and the person-centred stuff as another task and it's one that gets shoved down I think.

Traits of personhood-enhancing care

Traits of personhood-enhancing care referenced by participants include: competency and friendliness, respect, honesty and trust, knowing the person, empowerment and reassurance. While there are no significant conflicts amongst the groups on this sub-theme, some qualities are emphasised more strongly by one group than another. There is significant consensus on the need for friendliness across all groups. Friendliness is a catchall phrase for talking with the person, creating a sense of warmth, belonging, acceptance, being pleasant and being open with the person with dementia. All of the participants with dementia found positive things to say about the formal care they receive, with many describing formal carers as nice and good, conveying competency, as well as concepts such as kindness, reliability and availability. Family carers place a strong emphasis on competency and refer to how some formal carers are amazing. James, a family carer, sees personality as important but also competency and kindness:

Say that would be kind of a pleasant personality we'll call it would be one major thing I'd say in the job. But then how good or kind they'd be after that would be another next question.

Almost all participants reference the importance of respect, honesty and trust to supporting personhood. Hallmarks of respect include being treated with compassion, flexibility, not being patronised, being patient, communicating one to one, respecting people's preferences and respecting privacy and space. Half of the participants with dementia refer to how important honesty is in the formal care relationship. Nuala, a participant with dementia, emphasises how honesty, truth and respect are important to her:

Interviewer: What's important to you in how the, the staff, the health-care staff see you and interact with you, how would you like them to think of you?

Nuala: I'd like them to have respect for me.

Interviewer: Ok.

Nuala: Oh yea and eh respect my truthfulness and honesty.

While honesty is not emphasised as strongly by the other two groups, they do refer to trust. Formal carers place the strongest emphasis on trust, identifying it as crucial to developing a good formal care relationship.

Almost all of the participants reference how critical knowing the person with dementia is to supporting personhood in formal care, with participants with dementia also explaining how it is important to know the care staff well. For formal carers, knowing the person involves: knowing their preferences, their routines, understanding who they are, engaging and connecting with the person. Noreen, a family carer, describes how one formal carer connected with her husband by getting to know him:

Talk to him and ask him and just let him talk, draw him out what he likes, she knew in no time, he likes dogs, he likes farm animals, she was from the background, she let him talk.

The majority of formal carers reference empowerment and supporting the person with dementia to live well. This includes supporting independence, enabling the person to participate in interests, not highlighting mistakes, and assisting the person with dementia to find purpose and meaning in life. Empowerment is not referenced as much by the other two groups, but a minority of participants with dementia conceptualise good care as supporting the person with dementia to live as independently as possible. Maeve, a participant with dementia, explains her frustration in trying to find the right type of support:

If it was just something just to support me to help me to do things as opposed to doing it for me.

Discussion

This study found consensus on the core elements of personhood incorporating: interests and preferences; lifecourse experiences; social interaction; family; and place. The findings reflect both theoretical and empirical evidence on the self (Sabat and Harré, Reference Sabat and Harré1992; Sabat and Collins, Reference Sabat and Collins1999; Batra et al., Reference Batra, Sullivan, Williams and Geldmacher2016) and on relational personhood (Kitwood, Reference Kitwood1997; Nowell et al., Reference Nowell, Thornton and Simpson2013; Borley and Hardy, Reference Borley and Hardy2017), including familial roles (Cohen-Mansfield et al., Reference Cohen-Mansfield, Parpura-Gill and Golander2006). This study provides further support for the inclusion of these core elements into person-centred care models (Brooker, Reference Brooker2007; Fazio et al., Reference Fazio, Pace, Flinner and Kallmyer2018). However, there is some ambiguity among stakeholders in relation to the continued existence of personhood as the disease progresses. Family and formal carers sometimes struggled to both accept and interpret changes to personhood over time, particularly if this involved behavioural elements. Sometimes, family carers’ negative conceptualisation of the person with dementia as childlike is a way of dealing with changing relationships arising from the disease (Seaman, Reference Seaman2020). The consequences of formal carers acting in the same way are even more fraught. If the latter do not see people with dementia as maintaining personhood throughout the disease, then the fundamental professional ethos of person-centred care may be lost (Malloy and Hadjistavropoulos, Reference Malloy and Hadjistavropoulos2004), leading to serious consequences for people with dementia (Hunter et al., Reference Hunter, Hadjistavropoulos, Smythe, Malloy, Kaasalainen and Williams2013). Further research is required into conceptualising and interpreting transient elements of the self (Harris and Keady, Reference Harris and Keady2009), and how all parties in the care triad deal with change. It is vital that the experiences of family and formal carers are acknowledged and that they are supported and better equipped to interpret, understand and deal with change.

Interpersonal barriers to supporting personhood outline the difficulties parties in the care triad experience. Research elsewhere has explored the complexity in trying to find balance in triadic care relationships (Quinn et al., Reference Quinn, Clare, McGuinness and Woods2012), and highlighted the importance of relationship-centred communication strategies (Adams and Gardiner, Reference Adams and Gardiner2005). Ultimately, for the formal care relationship to function well and support personhood, there needs to be a harmonious triadic relationship with, as one formal carer put it, everyone ‘singing from the same hymn sheet’. Supporting personhood requires a complex set of skills, which are about much more than providing personal or physical care. This study provides guidance to key enhancers for personhood, such as competency, familiarity and friendliness, respect, honesty and trust, knowing the person and empowerment, many concepts which appear in different guises in person-centred care models already (Kitwood, Reference Kitwood1997; Brooker, Reference Brooker2007). Training and education for effective communication are also critical in supporting personhood in dementia care. A recent discrete choice experiment on personhood in dementia care suggests that the public value flexibility and good communication highly and are willing to support new models of care exhibiting these qualities through additional taxation (Walsh et al., Reference Walsh, O'Shea, Pierse, Kennelly, Keogh and Doherty2020).

The structural barriers identified in this study indicate how the health and social care system in Ireland is not always supportive of personhood or person-centred (Donnelly et al., Reference Donnelly, O'Brien, Begley and Brennan2016). Formal carers are frustrated by time constraints, which hinder their ability to support personhood. Family carers and people with dementia sometimes feel that they have to accept unwanted and therefore inappropriate provision, thereby denying their right to have care and supports that are reflective of their personal needs and circumstances. A more person-centred system of care would see choice given back to the person with dementia and their families, but achieving that will require higher levels of public spending than is currently allocated to dementia. Recognising dementia as a disability (Shakespeare et al., Reference Shakespeare, Zeilig and Mittler2019) is, perhaps, the first step in restructuring current conceptualisations of care away from paternalistic models to more rights-based, social models of delivery.

There are two interesting differences in how the three groups conceptualise and support personhood. First, participants with dementia identify place as a core element of personhood much more than family carers or formal carers. There has been some theoretical discussion on place and personhood (Chaudhury, Reference Chaudhury1999, Reference Chaudhury2008), and the importance of ‘being in place’ has already been acknowledged in person-centred models (McCormack, Reference McCormack2004). Equally, international policy emphasises ‘ageing in place’ and creating ‘age-friendly countries’ (World Health Organization, 2020). Second, participants experienced and interpreted change in different ways following the onset of dementia. Family carers were most likely to experience difficulty interpreting changes to personhood, including seeing the person as ‘lost’ as the disease progresses. This, in turn, may impact on the culture of care in home care settings, including negatively influencing the behaviour of formal carers who provide care and supports in the home; culture matters for personhood and the provision of person-centred care wherever that care occurs (McCormack et al., Reference McCormack, Dewing and McCance2011). Further research is required to understand fully the impact of familial attitudes on personhood, on formal care provision and practices.

All of the formal carers reference how they seek to ‘find balance’ in their communication and care practices. Finding balance reflects an understanding of the care process, but it also sheds light on the pressures that formal carers sometimes feel in the face of resource and time constraints. Of course, we need to know more about the effect of these pressures on the embodied selfhood of care recipients through further observational and ethnographic studies (Kontos, Reference Kontos2005; Twigg and Buse, Reference Twigg and Buse2013). The findings of this study must be also viewed in the context of geography and location. How personhood is viewed among stakeholders in Ireland is likely to differ from other cultures and societies, pointing to the need for more comparative cross-country work. Overall, however, the research reveals a significant level of understanding and appreciation of the importance of personhood among people with dementia, family carers and formal carers in Ireland. The next step is to reform the organisation and delivery of care so that the gap between actions and words is reduced and the aspirations of the Irish National Dementia Strategy (Department of Health, 2014) can be realised.

Limitations

The absence of ethnographic methods in this study is a limit to exploring embodied selfhood. The potential for conducting in-depth observational methods was beyond the scope of this work.

Conclusion

This study provides insight into the multifaceted nature of personhood in dementia in formal care relationships. It points to how a deeper and more practical emphasis on the core elements of personhood is required when designing formal care models of provision for people with dementia. This includes making sure that provision is not only medical, but that psychological and social supports are also available. Supporting people with dementia to be socially active, to maintain relationships and interests, and to stay connected to family, place and community are central to a personhood model of care. Effective communication is also important in formal care provision, pointing to the need for further education and training to ensure that providers can help maintain and foster the human contacts and relationships that people with dementia need and want.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to the research participants in this study, for giving their time and sharing their perspectives and experiences.

Author contributions

Both authors conceived of the study and guided the study methodology. The data were collected by NH and were analysed by NH with support from EOS. Both authors contributed to the findings, discussion and final manuscript.

Financial support

This work was supported by the Irish Research Council (grant number GOIPG/2016/697); and the Health Research Board Ireland (grant number rl-2015-1587). The funders played no role in this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

Ethical approval for this study was provided by the National University of Ireland Galway Research Ethics Committee (University Ethics Reference 18-Jan-06).