Introduction

About 350,000 older people in England live in care homes, generally for the final months or few years of their lives (LaingBuisson, 2018; Age UK, Reference Age2019). It is estimated that about 70 per cent of people in care homes have dementia or severe memory problems (Alzheimer's Society, 2019). Their wellbeing depends on their experience of living in a residential facility and the quality of care they receive. In England, personalisation is seen as a core ingredient of high-quality care and efforts are being made to destigmatise the image of care homes as being a place of ‘last resort’ (Townsend, Reference Townsend1962).

However, there are conflicting narratives of personalisation in adult social care. In residential care, personalisation is often referred to as ‘person-centred care’ or ‘personalised care’ (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2015; Care Quality Commission (CQC), 2018), suggesting that personalisation is generally regarded as an aspect of care and caring and a dimension of good quality care (Owen and Meyer, Reference Owen and Meyer2012). It also highlights the centrality of the role of professional carers and their aptitude and ability to provide relationship-oriented care. In domiciliary care, in contrast, a competing narrative of personalisation emphasises individual choice and control, typically expressed as choice of carer and service, facilitated by a direct payment (Kendall and Cameron, Reference Kendall and Cameron2014; Woolham et al., Reference Woolham, Daly, Steils and Ritters2015; Glasby and Littlechild, Reference Glasby and Littlechild2016). While the relationship aspect may be implicit, as most service users deploy their direct payment to pay for individual care assistants, this second narrative foregrounds individualism, independence and autonomy. This conceptualisation of personalisation has also been associated with marketisation of adult social care in England, which casts people receiving care as ‘consumers’ or ‘clients’ (Spicker, Reference Spicker2013; Rodrigues and Glendinning, Reference Rodrigues and Glendinning2014).

Efforts have been made to integrate both concepts, with the ‘My Home Life’ study of the Joseph Rowntree Foundation arguing that ‘voice, choice and control’, and attention to people's wishes and preferences, are as relevant to people in care homes as to anyone in any other setting (Owen and Meyer, Reference Owen and Meyer2012). However, in practice, there can be tensions between these two concepts, with care homes giving priority to one or the other. Davies (Reference Davies, Nolan, Lundh, Grant and Keady2003) observed that nursing homes in England differ in their espoused styles of care home community involving residents, relatives and staff. She described homes which were organised around tasks and routines for the benefit of the organisation as ‘controlled communities’, focused on minimising risks but with little attention to the social and emotional needs of residents. This contrasts with organisations that are more customer-oriented and interested in providing quality care and privacy, but in which relationships between staff and residents remain ‘business-like’ and superficial (‘cosmetic communities’). A more positive model, in her view, termed the ‘complete community’, prioritised the emotional and social needs of residents and their wellbeing, and pursued this by fostering personal relationships between residents, families and staff (Davies, Reference Davies, Nolan, Lundh, Grant and Keady2003). In a similar vein, Trigg (Reference Trigg2018) distinguishes three approaches that care homes adopt to provide quality care for older people, which she describes as ‘organisation-focused’, ‘consumer-directed’ or ‘relationship-centred’, mirroring the three nursing home communities identified by Davies (Reference Davies, Nolan, Lundh, Grant and Keady2003).

In the following analysis, we have interrogated our data from interviews with care home managers to understand better how managers conceptualise their approach to personalisation enacted in the care home they manage, and what version, or which aspects, of personalisation they aspire to within their home. We use the term ‘care homes’ to include residential care homes (for people requiring personal care) and nursing homes (for people requiring personal and nursing care). We attempt to answer two questions: how do care home managers conceptualise the personalisation approach of their care home; and which types of personalised care do they aspire to in the homes they manage?

The aim of this paper is to understand better different approaches to personalising care present in the care home market in England. The objectives are to analyse the metaphors and conceptualisations care home managers provide in interviews; to reflect how these resonate with the relevant research and practitioner literature; and to develop a typology of approaches to personalising care in care homes. For the purpose of this analysis, we interrogate interviews with care home managers and the relevant research and practice literature using abductive reasoning (Schwartz-Shea and Yanov, Reference Schwartz-Shea and Yanov2012). In the interviews, some managers used metaphors such as ‘hotel’ or ‘family’ as opposed to ‘institution’ to describe how they approached personalisation in their homes. In our analysis, we have aimed to delve deeper into the meaning of these metaphors, as they reflect aspects of the two competing narratives about the relevance of choice and the importance of relationship building. We think of the typology we develop as a series of Weberian ‘ideal types’. Weber (Reference Weber1986) suggested using ideal types to analyse social phenomena by distinguishing pre-defined categories formed around salient characteristics, without these necessarily being mutually exclusive. In our analysis of the phenomenon that is ‘personalised care’, this process was iterative and ‘abductive’ as we moved between constructs present in the literature and metaphors and conceptualisations presented in interviews.

Background

There is growing interest internationally in investigating the meaning of ‘home’ in relation to long-term care (Hauge and Heggen, Reference Hauge and Heggen2008; Falk et al., Reference Falk, Wijk, Persson and Falk2012; Bigonnesse et al., Reference Bigonnesse, Beaulieu and Garon2014; Klaasens and Meijering, Reference Klaasens and Meijering2015; Rijnaard et al., Reference Rijnaard, Van Hoof, Janssen, Verbeek, Pocornie, Eijkelenboom, Beerens, Molony and Wouters2016; Eijkelenboom et al., Reference Eijkelenboom, Verbeek, Felix and Van Hoof2017; Power, Reference Power2017; Hatcher et al., Reference Hatcher, Chang, Schmied and Garrido2019). Studies of residential care often highlight the importance of care homes making residents feel ‘at home’ and developing a ‘home-like’ or ‘homely’ environment. ‘At homeness’ has been linked with improved quality of life of residents and is associated with feelings of belonging, familiarity, privacy and safety (Cooney, Reference Cooney2012). However, there is no agreement as to what constitutes ‘at homeness’ in care homes (Molony, Reference Molony2010).

The feeling of being at home is often associated with the image of the domestic home, the environment, it is assumed, that older residents are most familiar with, although it has been argued that such imagery – the family home as a safe haven organised around a nuclear family, with its gendered ordering of tasks – is overly simplistic (Dyck et al., Reference Dyck, Kontos, Angus and McKeever2005). For many older people, the experience of being in their own homes is likely to be more complicated: the domestic environment can be a lonely place and burdensome to maintain in the face of age-related decline, while at the same time experienced as a place of autonomy and self-actualisation (Boyle, Reference Boyle2004; Bally and Jung, Reference Bally and Jung2015). Feeling ‘at home’ is a much more ‘complex blend of emotional, cognitive, behavioural and social bonds to a particular place’ than the idealist imagery suggests (Cooney, Reference Cooney2012: 189). Yet the domestic home remains the prototypical place of care that combines both individual choice and the closeness of the care relationship associated with family bonds.

Individual choice and decision-making

Individual choice features prominently among the descriptors of ‘at homeness’ (De Veer and Kerkstra, Reference De Veer and Kerkstra2001; Molony, Reference Molony2010, Rijnaard et al., Reference Rijnaard, Van Hoof, Janssen, Verbeek, Pocornie, Eijkelenboom, Beerens, Molony and Wouters2016). Unlike in domestic homes, people living in care homes usually do not have the option to decide who they live with, rather, they are faced with living with a collection of strangers, whose habits, moods and manners have to be tolerated. Living in a care home, therefore, takes ‘getting used to’ and involves an effort of substantial adjustment on the part of a new resident. Cooney (Reference Cooney2012) notes that residents who move into a care home of their own volition are often happier and more likely to feel at home than those who were placed there by their family or social services.

In the care home context, choice and control also translate into how boundaries between public and private spaces are maintained and navigated (Boyl, Reference Boyle2004; Klaasens and Meijering, Reference Klaasens and Meijering2015, Bangerter et al., Reference Bangerter, Van Haitsma, Heid and Abbott2016). Invasions of privacy are pre-eminent characteristics of institutional living, in which members of staff enter residents’ personal spaces such as bedrooms or bathrooms without asking for consent. Other choices within the care home include activities of daily living, such as getting out of or into bed, dressing, eating a meal or having a drink. It also includes how people spend their time and with whom they spend it. Are they allowed, in principle and in practice, to leave the home if they so wish? Such decisions have implications for the safety of people with diminished capacity, be this physically because of their frailty and concerns about prevention of falls, or cognitively such as in cases of advanced dementia (O'Sullivan, Reference O'Sullivan2013; Clarke and Mantle, Reference Clarke and Mantle2016; Manthorpe and Samsi, Reference Manthorpe and Samsi2016).

Frameworks for person-centred care tend to emphasise ‘joint decision-making’ as an important feature of personalisation (Brooker, Reference Brooker2003; Wilberforce et al., Reference Wilberforce, Challis, Davies, Kelly, Roberts and Clarkson2017; Social Care Institute for Excellence, 2019). In theory, decisions should be made by the resident, with carers and managers playing a supportive role. Yet in practice, it may not always be possible to shift power entirely from carers to residents, both for reasons of residents’ capacity to make decisions and for reasons such as time constraints, safety regulation and professional judgement (Wilberforce et al., Reference Wilberforce, Challis, Davies, Kelly, Roberts and Clarkson2017). In addition, decisions taken in a communal context are likely to impact on other residents, as well as on carers.

Care and caring relationships

A second body of literature relevant to this analysis discusses the role of the care relationship for the wellbeing of residents in care homes, especially, but not exclusively, people with dementia (Brooker, Reference Brooker2003; McCormack and McCance, Reference McCormack and McCance2006; Hutchinson et al., Reference Hutchinson, Rawson, O'Connell, Walker, Bucknall, Forbes, Ostaszkiewicz and Ockerby2017). Person-centred care emphasises the importance of staff knowing the residents of their care home, to value their past and their experiences, and to appreciate their preferences and personalities. The attitudes and behaviours of care providers are central to the delivery of person-centred care, and to the physical and psychological wellbeing of the resident with dementia (Doyle and Rubinstein, Reference Doyle and Rubinstein2014; Dichter et al., Reference Dichter, Trutschel, Schwab, Haastert, Quasdorf and Halek2017; Fazio et al., Reference Fazio, Pace, Flinner and Kallmyer2018). A classic portrait of institutional care describes the absence of human empathy and support (Townsend, Reference Townsend1962; Klaassens and Meijering, Reference Klaasens and Meijering2015). Kitwood (Reference Kitwood1997) described the ‘malignant social pathologies’ that characterised carers’ treatment of people with dementia, such as infantilising, labelling or disempowering behaviour. It is worth noting that such attitudes and behaviours do not happen without context, but reflect that people with dementia are not valued, and often not taken seriously, by society (Brooker, Reference Brooker2003). An empathetic, compassionate attitude is therefore seen as essential to foster the positive relationship that values residents as people deserving respect undiminished by disability or cognitive decline, in the same way in which staff should be valued by managers and families (Brooker, Reference Brooker2003).

However, there can be tension between the professional responsibilities of staff and their role as carers ‘who care’ (Rockwell, Reference Rockwell2012; Lynch et al., Reference Lynch, McCance, McCormack and Brown2018). For example, staff have to balance compliance with regulation and with other aspects of caring within the care relationship. Staff are professionals, accountable within a managerial hierarchy, guided by a complex regulatory environment, as well as multiple forms of collaborations with other professionals, and expected to be responsive to pressures and expectations from families and others. There is also an emotional cost to care work that is often not adequately articulated, let alone appropriately remunerated (Johnson, Reference Johnson2015). Nakrem et al. (Reference Nakrem, Vinsnes, Harkless, Paulsen and Seim2012) note that relationships between residents and staff are often ambiguous. Residents experience staff as kind and competent, as well as busy, preoccupied and not immediately available because of high workloads and competing priorities. The presence of professional carers can be reassuring and at the same time exacerbate residents’ feelings of helplessness and dependence. Thus, the care relationship, despite the ambitions expressed in various frameworks and policy and practice documents, can be fraught with ambiguities and ambivalence.

Methods

To achieve the study's aim and objectives, we use interviews with managers of care homes in England and draw on the research and practitioner literature relevant to personalising care in care homes to contextualise and deepen our analysis. We built our analysis on the findings of a larger study, which included an extensive review of the practitioner and research literature on concepts and approaches to personalising care in care homes. The methods of identifying, selecting and analysing studies are reported in detail elsewhere (Ettelt et al., Reference Ettelt, Damant, Perkins, Williams and Wittenberg2020). For this analysis, we added a further body of research to include the themes of ‘home’ and ‘at homeness’, to contextualise the development of the typology.

Support for recruitment of care home managers was provided through the National Institute for Health Research's (NIHR) Clinical Research Network (CRN), following adoption of the study on the NIHR CRN portfolio in May 2018. All CRN regional leads were contacted directly by a member of the research team with an invitation letter, information about the purpose and approach of the study, and our criteria for recruitment. Further information about the study was provided directly by a member of the research team (LW) where requested. To enable recruitment, the CRN leads used one or more of the following methods: electronically disseminating written information about the study through their research networks; directly contacting managers from their Enabling Research in Care Homes (ENRICH) networks with information about the study; and disseminating information about the study to managers during one of their ‘research network visits’ to care homes. Because several methods were used at the CRN leads’ discretion, we have no information about how many care home managers were approached for this study in total.

All managers expressing an interest in participating in an interview were invited to contact a member of the research team by email or telephone. After they established contact, their name and contact details were entered on to a database and they were advised that a member of the team would contact them if they met the criteria required for selection. The sample was selected purposefully to include care homes that were ‘for-profit’ and ‘not-for-profit’; homes with a small, medium or large number of residents; stand-alone homes and homes that formed part of a group or chain; and a few homes that served specific population groups such as faith communities. The sample also included care homes from a variety of geographical regions in England, operating in either urban or rural settings and in receipt of different quality ratings from the CQC. All care home managers from care homes meeting the sampling criteria were then contacted by a member of the research team and arrangements were made to interview.

Semi-structured interviews were carried out with 24 out of 25 care home managers recruited into this study. One manager agreed to participate but did not find the time for an interview. Interviews were conducted between June and September 2018. Interviews were conducted by all members of the research team, all of whom are experienced interviewers with relevant training. Managers were interviewed at their place of work in person or over the telephone. Interviews lasted between 35 and 90 minutes, were audio recorded with consent and transcribed verbatim. Interviewees were given a gift voucher of £30 in compensation for their time.

Interview topics included: characteristics of the care home; views on the meaning and practical implications of personalisation in care homes; how personalisation related to different levels of care needs; measures taken to promote personalisation, including the types of choices available to residents, how staff promoted joint decision-making, helped service users to maintain their sense of identity and encouraged involvement in the community of the care home; staff training, recruitment and management; barriers to promoting personalisation; and the role of the CQC.

The 24 care homes from which managers were recruited to the study were located in 17 towns in six regions in England (no care home managers were recruited in London, the North-East or East Midlands). They included a mix of small, medium and large care homes; the smallest catering for nine residents and the largest for 127 residents in total. Fourteen of the 24 managers recruited led care homes that were part of a group of care homes and, of these, three belonged to large groups of over 60 homes within the United Kingdom, and four belonged to smaller groups of between two and four homes. Ten care homes operated as free-standing homes and these accounted for four of the six care homes recruited to the study that had 50 residents or more. All care homes provided care for adults aged 65 years and over, although some managers said that a few of their residents were younger.

Table 1 provides a summary of the characteristics of the care homes and managers interviewed. Two-thirds of the care homes were private for-profit businesses and one-third were not-for-profit organisations. Seventeen care homes were registered for nursing and residential care, seven were registered for residential care only. Managers of nine homes stated that all or most of their residents were self-funding their care, ten reported receive funding from the National Health Service or a local authority, and five had both self-funded and publicly funded residents.

Table 1. Characteristics of care homes and interviewees

Note: LA/NHS: local authority/National Health Service.

All care homes whose managers were interviewed for this study provided care for people with varying degrees of dementia, alongside other conditions, and most were registered for dementia care with the CQC. Managers of the two care homes without such a registration explained that they may have residents with dementia as a secondary diagnosis. Two-thirds of the managers interviewed had a background in clinical nursing and most of these were currently registered to practise as nurses. Among the 24 care homes selected, three were rated as ‘outstanding’, 15 as ‘good’ and six as ‘requiring improvement’ at their last available CQC rating.

Interview data were analysed using abductive reasoning, working with themes and ideas from a literature review we carried out for a separate arm of the larger study (Ettelt et al., Reference Ettelt, Damant, Perkins, Williams and Wittenberg2020), while also conducting additional literature searches to explore themes emerging from the interviews (Schwartz-Shea and Yanov, Reference Schwartz-Shea and Yanov2012). The latter was particularly pertinent with regard to the themes of ‘home’ and ‘feeling at home’ around which a substantial body of work has emerged. This interest in ‘home’ shares many features with the interest in personalisation and person-centred care (e.g. improving the quality of care; attention to the wellbeing and emotional needs of residents; the importance of continuity and the connection to place in the process of ageing), yet studies investigating concepts of ‘home’ tend not to be fully integrated in the discussions of personalised care. This analysis aims to redress this imbalance by exploring the different types of ‘home’ that care home managers aspire to providing to their residents.

The development of the typology was an iterative process taking inspiration from the interviews with care home managers, with managers using different metaphors (e.g. ‘a hotel service’, ‘like a family’) to describe their ambition for the type of personalised care they aimed to provide in the care home they managed. We used these metaphors as themes to interrogate the research and practitioner literature on personalisation, person-centred care and ‘at homeness’ in residential care, finding commonalities and investigating contrasts between the two main narratives of personalisation: the importance of choice and the quality of the relationship between residents and carers.

Findings

The following section presents the findings from the analysis of the interviews with care home managers asked to reflect about their understanding of personalisation and the personalised practices they promote in the homes they manage. Three categories have emerged from the interviews, which resonate with the debates in the literature about the meaning of living in a care home. These categories are the care home as an institution, as a family and as a hotel.

Care home as an institution

In our interviews, the ‘institution’ was a firm point of reference for managers. Managers evoked the care home as an ‘institution’ when they wanted to describe the type of home from which they would like to distance themselves. The image was frequently used for contrast, to provide a negative comparator to the efforts made by staff to personalise care and make people feel ‘at home’.

Well, the philosophy of care is basically that this is the person's home, so everybody here, nobody wants to go into 24-hour care, it's never really something people want to go in. So, the idea is that this is going to be their home, and we make it as much [like] home. We don't like to think of it as the traditional type of care home in an institutionalised setting. We do try to make it as personal and as friendly as possible. (Manager 21)

The image of the care home as an ‘institution’ is perhaps the most enduring one in the literature and the public imagination. It is captured by the theory of the ‘total institution’ established by Erving Goffman in his essay collection Asylums, described as places of ‘residence and work where a large number of like-situated individuals, cut off from the wider society for an appreciable period of time, together lead an enclosed, formally administered round of life’ (Goffman, [Reference Goffman1961] Reference Goffman1991: 11). Residents living in the institution Goffman describes are separated from the outside world, while staff have a life outside the institution and are able to traverse its boundaries. In addition to care homes, the concept has been applied to other forms of communal living such as psychiatric hospitals, military barracks and monasteries. Townsend's (Reference Townsend1962) work on care homes as ‘the last refuge’ was another seminal piece cementing the negative image of care homes in which the frail elderly were subjected to routines they cannot escape while having little opportunity to express themselves or access the outside world.

Evoking the ‘institution’ was all the more powerful as it conjured up the image of people losing both their freedom and their ability to determine how they spend their lives upon entering a care home. Some managers therefore likened the institution to a ‘prison’ that people cannot escape from and in which people are not treated as human beings but as commodities that are stored, rather than cared for. As one manager noted with regret, the care home as an institution was still the dominant imagery among people entering care and members of the public (Manager 20).

In the managers’ accounts, the ‘institution’ was associated with routinised, regimented approaches to organising care, evoking the military as an example of a ‘total institution’. Although this was commonly seen as ‘a thing of the past’, several managers noted that it was impossible to organise care in a care home without a degree of routinisation and scheduling. Aspects of the institution were seen to creep back into approaches to personalisation. Some managers conceded that providing individualised care was always more demanding and more time-consuming than not individualising care, and thus could be difficult to deliver consistently in the resource-constrained context of most care homes.

The care home as an institution combines distant hierarchical relationships between carers and residents, and sterile, routine-driven arrangements of communal life. Both are associated with ‘batch living’ (Goffman, [Reference Goffman1961] Reference Goffman1991) and routinisation of tasks that strip away individual identities (Gilleard and Higgs, Reference Gilleard and Higgs2010), afford residents little privacy or personal decision-making space (Klaassens and Meijering, Reference Klaasens and Meijering2015), and prioritise efficiency and risk minimisation over the wellbeing of the individual (Davies, Reference Davies, Nolan, Lundh, Grant and Keady2003). In today's discourse, the institution has almost mythical qualities reflecting the care home of the past with which nobody operating a care home today wants to be associated; and yet, the image of the ‘institution’ appears to have survived not only in reports of poor care, but as ‘a kind of social and cultural “black hole”’ in which the infirm aged disappear towards the end of their lives (Gilleard and Higgs, Reference Gilleard and Higgs2010: 121). It appears in the use of set routines, especially in nursing homes (Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Rolph and Smith2010); the often blurred boundaries between communal and private space; and the tendency of regulatory compliance to prevent residents taking risks and executing tasks they would normally do in their own homes (e.g. boil water for a cup of tea; handle a kitchen knife). In these respects, the care home as an institution is as far removed from feeling like ‘home’ as a hospital, although without providing the sense of ‘ontological security’ a hospital may provide as a place of healing (Giddens, Reference Giddens1991; Jones, Reference Jones2015: 255).

Some managers noted the influence of nursing services on task orientation, which closely resembled care provided in hospitals. Nursing care was also associated with a tendency to avoid risks to residents, even if this might mean that residents would be less able to execute their own wishes (Manager 5). There were concerns about safety and the ability of the manager to be able to demonstrate compliance with regulation and the home's ‘duty of care’ (Manager 3). Such concerns were also seen as a response to external regulation and the need to be able to document residents’ choices that might constitute a risk. One manager conceded that their home had invested in a surveillance system in the communal areas of the home to be able to understand, and presumably demonstrate to families, whether incidences of harm to residents were the responsibility of the home (Manager 32). While it may be understandable that managers felt under pressure to justify themselves, such practices were reminiscent of the disciplinary surveillance associated with prisons (Foucault, Reference Foucault1977). The example also illustrates the shifting boundary between communal and private space in the home in which residents could experience privacy and would be trusted to be left on their own. However, attitudes towards risk taking varied substantially between managers, in part reflecting the needs of different care home populations, such as people with advanced dementia. These differences in experiences tended to underpin different accounts of approaches to surveillance and protection (e.g. whether residents were able to leave the home on their own or smoke outdoors during bad weather if they so wished).

Many managers described trade-offs between personalisation with risk management and the need to organise care effectively and efficiently within the constraints of the home. The need to uphold some routines therefore meant that personalisation happened at the margins of these routines (Manager 21). This seemed particularly pronounced in care homes that provided nursing care to a larger number of residents requiring substantial personal care such as feeding, washing, dressing and continence care:

It's quite difficult. With the best will in the world, with day-to-day functioning of a very busy care home with very, very dependent people who have predominantly physiological needs, so they're mostly incontinent, mostly need feeding. Out of the 60 people, I probably have 40 that need to be fed and are incontinent. So therefore, with my hand on my heart, a person's previous life and experiences can be merged into just the normal day-to-day running. (Manager 3)

Although all managers interviewed for this study agreed with the aim of personalisation and described a wealth of approaches to personalising care, some conceded that it was not always easy, and sometimes impossible, to organise care without recourse to routines, task orientation and risk management associated with institutionalised care, with some being less optimistic about their ability to provide a truly personalised service than others (Manager 14).

Care home as a family

The care home as a ‘family’ was the version of a personalised care home most popular with managers. Treating residents ‘as family’ was seen by many managers as the model of personalised care that they aspired to within their home, built around close relationships and a sense of equality between residents and carers.

In terms of, I'm talking about the staff really, how the staff create the culture, that it's about belief and it's about enjoyment and making sure that they're part of the family, that is … Again, you did ask me and I'm probably talking about this in a very long-winded way, but the heart of family life in residential care is that we're all in it together. We're all part of this process of family life. (Manager 24)

By evoking the ‘family’ as the ideal version of the care home community, managers elevated the care relationship as the all-important ingredient to personalised care, appropriate for people in need of care and valued by both residents and staff. Managers emphasised the necessity for residents, their families and staff to trust one another, to be able to build close relationships.

The care home as a family emphasises communal living, but in a relationship-oriented way that is compatible with person-centred care and its emphasis on positive care relationships (Brooker, Reference Brooker2003). It underlines the need for compassion, emotional investment and empathy, while also stressing the importance of homeliness, permanence and familiarity within the home (Dewar et al., Reference Dewar, Adamson, Smith, Surfleet and King2014). It is most easily equated with care provided at a domestic scale, even if in practice this will include dozens of residents and staff, with homely interiors and home-like practices (De Rooij et al., Reference De Rooij, Luijkx, Spruytte, Emmerink, Schols and Declercq2012). It is often seen as most suitable for people with dementia both with regard to the emphasis on the care relationship but also because it is expected that a home-like environment will be more familiar to people, and will therefore help them to orientate themselves more easily when they enter residential care (Smith, Reference Smith2013).

Managers described various techniques used by staff to foster positive, trusting relationships with residents, for example by showing affection (giving a cuddle or a kiss) and sharing jokes. Other care home managers aimed to make relationships less formal by doing away with staff insignia such as uniforms or titles (Manager 4; Manager 35) and by using terms of endearment, although staff were reminded to be judicious in their use of informal behaviour (Manager 27).

Importantly, being part of the family was seen as fully compatible with exercising individual choices, which were encouraged and facilitated by staff respecting residents’ wishes and decisions, rather than influencing them to suit their own professional ideas of residents’ appropriate behaviour. Indeed, the ability to make decisions enabled residents to be themselves and to feel ‘at home’ in the care home. Yet managers also tended to emphasise the communal aspects of living in a care home, the type of community they aspired to creating and the activities they would do together within the home:

I think it's about recognising who people are and what their choices are and making sure that we can offer them what they want and so it becomes their home. It feels like their home and we become part of a bigger family for them. (Manager 28)

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the ‘family’ was often evoked by managers who operated small to medium-sized care homes, with some saying that caring for a smaller number of residents enabled them to respond flexibly to residents’ wishes, even at short notice (Manager 25). Size mattered in the accounts of managers, with managers of large homes also often referring to having smaller ‘units’ or ‘wards’ to ensure ‘familiarity’.

Another feature of the family model of personalisation mentioned in interviews was enabling residents to participate in domestic activities. These were seen as a method of encouraging community and a sense of belonging, but also of creating continuity between residents’ lives before and after entering the care home. Such activities could include dusting, washing up, tidying, ironing and gardening, some of which could blend in with programmed activities (Manager 28), while others reflected individual residents’ desire for useful occupation that the care home aimed to accommodate (Manager 35; Manager 29). Managers also noted that such efforts often remained symbolic, with residents wanting to ‘help’ staff while no longer being able to execute such tasks or remembering that they actually disliked domestic chores:

We've had the resident that said to me that she missed ironing so much. Now how can anyone miss ironing? But, you know? So, I asked the laundry girl to take the ironing board down to the quiet lounge where this lady was sat and said, could she support her in ironing some of the bedding? And I think she only ironed a couple of things and she said she'd forgotten how she hated ironing. (Manager 23)

In their study of care home laundry, Buse et al. (Reference Buse, Twigg and Nettleton2018) distinguished the visibility of laundry compatible with the domestic home from hotel-like handling of dirty washing ‘behind the scenes’. Domestic tasks like ironing laundry or laying the table can connect residents with their own domestic past and thus help to personalise their experience of the home. However, while these tasks can promote identity and social engagement (and are often referred to as ‘meaningful’ activities), the authors also note a tension between the aspiration of domestic living and the communal, institutional aspects of home life, such as a lack of privacy around ‘bulk’ washing of residents’ personal items (Buse et al., Reference Buse, Twigg and Nettleton2018). The family model is also associated with de-emphasising hierarchies and aspiring to relationships built on equality, companionship and compassion. Yet while these are aimed at increasing the emotional security of residents, sustaining close relationships equally with all residents (i.e. without picking ‘favourites’) requires substantial emotional labour from staff (Davies, Reference Davies, Nolan, Lundh, Grant and Keady2003; Johnson, Reference Johnson2015).

Evoking the idea of the ‘family’ was seen as an antidote to potential social isolation of residents, by emphasising the role of the care home community and encouraging friendships between residents, as well as positive relationships with staff. This also extended to the use of physical space with some managers explaining how they used the care home to enable family occasions such as celebrating residents’ birthdays or having ‘a little party’ for other reasons (Manager 30; Manager 31). Celebrating people's lives, be it birthday celebrations, hosting wakes or organising events for remembrance were also seen as an important contribution to the lives of the residents in the home and their families (Manager 31; Manager 35; Manager 28).

Care home as a hotel

The care home as a ‘hotel’ was an image evoked as an alternative model of the personalised care home, although, on the whole, its use in interviews was rarer than reference to ‘institution’ and ‘family’, and produced a less-coherent image of care. Reference to this model emphasised individual choice and a customer relationship between the resident and home.

Managers referred to the care home as a ‘hotel’ to indicate the quality of their services and the aspiration of the home as a place of choice rather than a place of necessity. This aspiration applied to the interior design of the care home, as well as to the provision of services. For example, one manager talked about the dining room as being presented as a restaurant, in which residents find menus on each table from which they could choose and order a meal they liked (Manager 28). This manager also likened staying in the care home to being on an expensive holiday, a metaphor they used in staff training to remind colleagues of the level of service, comfort and courtesy expected from them vis-à-vis residents, who were cast as paying customers:

At the end of the day, we only want what's best for our residents and that can change on a daily basis so we have to change with it. Part of our training is if we went on holiday and paid £850 a week what would we expect? (Manager 28)

The care home as a hotel is often associated with upmarket residential homes caring for privately funded residents and the image they present about themselves (Buse et al., Reference Buse, Twigg and Nettleton2018). The emphasis here is on choice, privacy and comfort, which can be portrayed as provided by a hotel rather than a facility specialising in personal care and support (the ‘cosmetic community’ of Davies, Reference Davies, Nolan, Lundh, Grant and Keady2003). This image of the care home is compatible with the consumer model of health and social care, in which residents are cast as ‘customers’, ‘clients’ or ‘guests’ (Trigg, Reference Trigg2018; Stevens et al., Reference Stevens, Moriarty, Harris, Manthorpe, Hussein and Cornes2019). It is also expressed in the architectural design of some homes, which gives prominence to generous reception areas, private bedrooms with en-suite bathrooms, and facilities looking ‘clean’ and ‘nice’ rather than ‘cosy’ or ‘domestic’ (O'Dwyer, Reference O'Dwyer2013). They are more likely to compare themselves to ‘smart hotels’ or ‘stately homes’ in which people are waited on rather than recipients of care (Buse et al., 2017). This model is less emphatic about the personal relationships within the home and there is likely to be substantial tension between the model of the resident as the service consumer and the intrusion, intimacy and ‘messiness’ associated with personal care, which some argue makes this model inappropriate for the care of people with limited cognitive capacity and substantial physical care needs (O'Dwyer, Reference O'Dwyer2013). Even managers who felt that their home did not provide a hotel-like service felt that this was how competitors in the sector would portray themselves, especially those who attracted self-funding individuals, and that this was a business model that was appreciated, even expected, by those people who were able to afford it (Manager 29).

There were frequent examples of managers using customer relations techniques to elicit feedback on service quality and resident satisfaction. Asked whether and how managers encouraged shared decision-making between residents and professionals, some managers noted that they would regularly ask residents and their families for feedback on their services. Many homes used customer satisfaction surveys to be completed by residents or family members if residents did not have sufficient capacity to complete them. Such techniques were reminiscent of those used in service industries (such as hospitality or airlines); however, most managers conceded that they should only be used in combination with other feedback mechanisms and that personal rapport with residents and families was essential to maintain a positive relationship and positive service experience.

This perspective firmly prioritised the customer experience, while casting staff as service providers whose needs were seen as secondary to the needs and wishes of the customer. When asked how to deal with a situation in which a resident and a staff member did not get along, a service-oriented manager argued that the resident's views counted more than those of the staff member, emphasising the transactional relationship between a paying customer and the provider who received a wage for delivering a service:

The bottom line is, if somebody needs something, you meet those needs. How you feel is secondary. Client needs come first. They pay our wages. Let's be mindful that they're not here for us. We're here for them … We're the hired help … They're paying our wages, and they pay a lot of money to live in a home. And they have a right to be treated with dignity and with respect. (Manager 30)

However, while such a response emphasised the consumer rights of residents, there was also a risk of downplaying their level of care need, e.g. one manager referring to the care home as ‘a hotel for older people … for people who might need some help with the laces on their shoes’ (Manager 20).

Others noted that while they used the image of the ‘hotel’ as an ambition against which to measure the standard of their service provision, in their experience there was a limit to the extent to which this would entail a shift in power from professionals to residents:

I can't say I've noted it [i.e. a shift in power] with the residents. I'd be telling fibs if I said, oh yes – I can't say I've noted an equality with the residents. But we do try our very best to … you know, we are here to serve you, you are paying for a service, this is a service industry, you know, if you were staying in a five-star hotel, this is what you should be expecting in our home. (Manager 17)

Thus, while some managers aspired to empowering residents by emphasising their role as customers, it was not always seen as practical given that many older residents were highly dependent on the services provided to them, irrespective of whether they paid for the service.

Discussion and conclusion

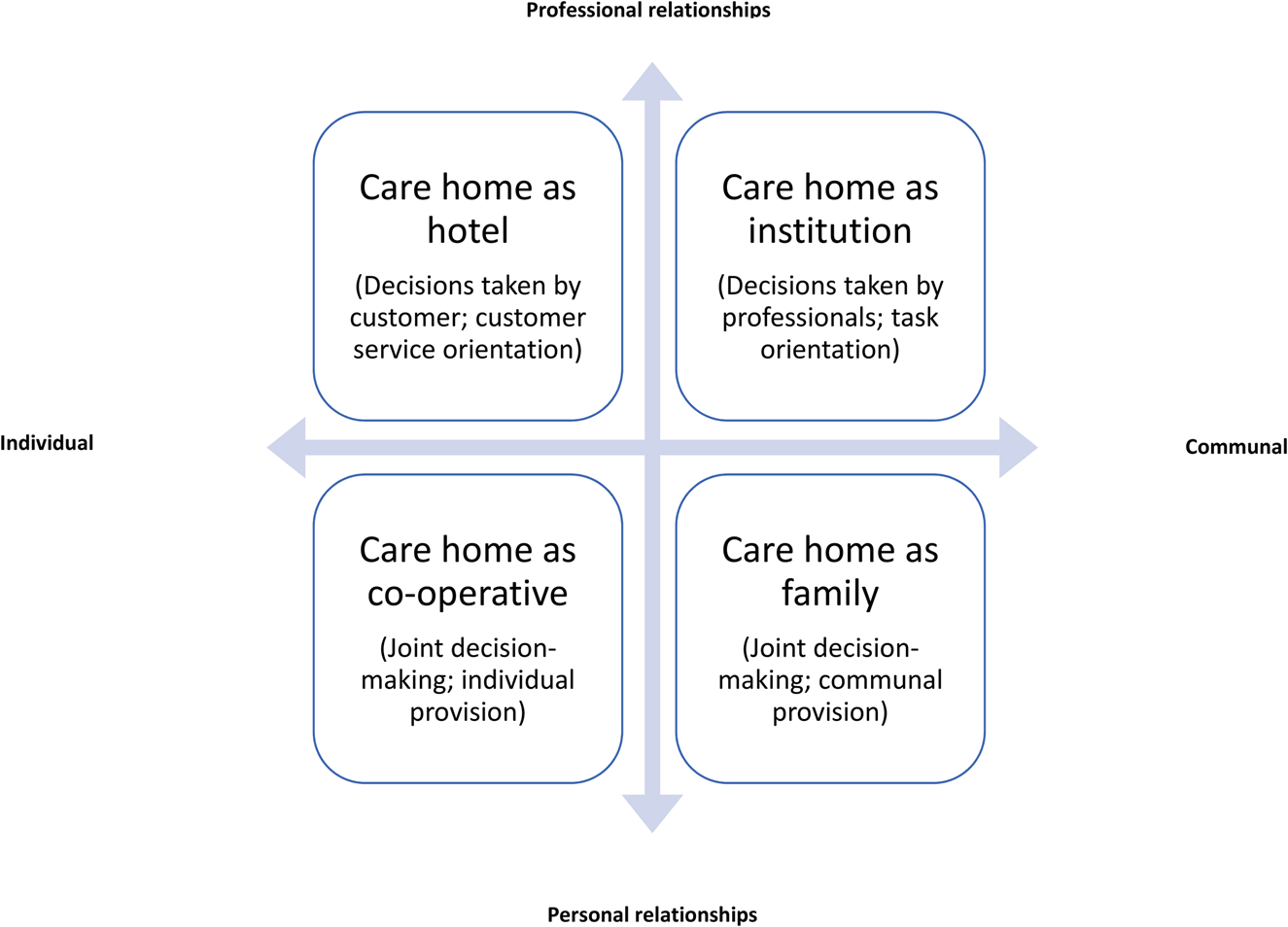

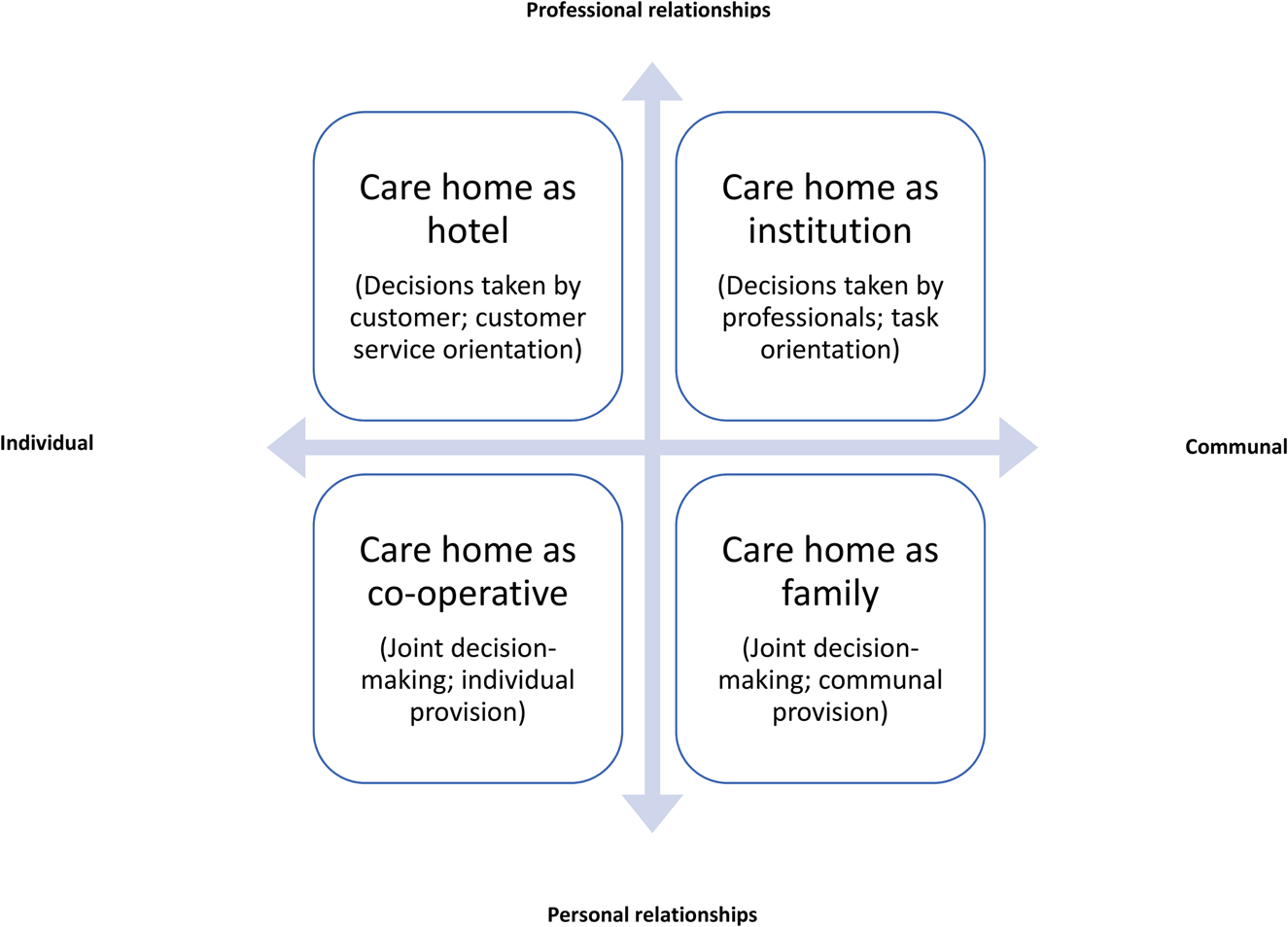

In the analysis above, we examined how care home managers interviewed for this study conceptualised the personalisation approach they aspired to in the care homes they managed. We found three distinct concepts: the care home as an institution, a family and a hotel, which we have discussed in the context of the research and practitioner literature we identified on the subject. We have mapped these concepts on to the two variables identified in literature on personalised care: the importance of the care relationship and the level of resident choice and decision-making aspired to in the care home. This has resulted in a typology of three ‘types’ of personalised (and non-personalised) care in care homes, to which we suggest adding a fourth type, discussed below (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Four types of care home.

While none of the managers would like their care home to be seen as an ‘institution’, some managers noted that there were elements of routinisation, task orientation and risk aversion reminiscent of institutional care, especially perhaps in the organisation of nursing care for those with high dependencies. This raises the question as to whether these managers tolerate practices that are incompatible with the idea of personalised care or whether some aspects of residential care necessitate a series of trade-offs, between individual and collective provision, spontaneity and the need for task completion, risk taking and ensuring residents’ safety. Findings suggest that such trade-offs become more pertinent as residents’ care needs increase, with high-dependency nursing care perhaps most likely to be routinised and ‘institutional’ (Milligan, Reference Milligan2009; Wada et al., Reference Wada, Canham, Battersby, Sixsmith, Woolrych, Fang and Sixsmith2020), with personalised care, as one manager described, only happening at the periphery.

Creating a family-like community was the most popular aspiration among managers. This type emphasised close, trusting relationships between staff and residents and a desire to treat everyone as equals. Many care home managers spoke about offering activities that are typically associated with the domestic home such as participation in household tasks or the celebration of family occasions. For managers, enabling a family-like community was not incompatible with promoting choice, yet these choices tended to be embedded in the communal context of the home. In this study, we only spoke to managers of homes to understand how they conceptualised their approach, not to care staff nor residents. It would be interesting to compare managers’ views with the views and experiences of residents and staff, to understand whether managers achieved their objective of creating a family-like home and explore their perspectives on the benefits, and limits, of such ‘family-like’ relationships. It is possible, for example, that the aspiration of a ‘family-style’ home is more popular with managers than residents or staff, who may feel the difference between their own (past or present) experience of the domestic home and the care home more succinctly.

Managers referring to the family-like approach of their home emphasised the ability of staff to empathise and connect with residents (and families), stressing the emotional labour of care workers (Hochschild, Reference Hochschild1979; Johnson, Reference Johnson2015). However, this model rubs against the managerial ethos of many homes, which, after all, are workplaces in which staff and their managers are ultimately responsible for the wellbeing of residents and accountable to local authorities, professional bodies and the CQC. While the findings suggest that such tensions may be less pronounced in smaller than in larger care homes, tensions between homes being residents’ home and a workplace have also been reported for earlier models of small, proprietor-run homes with four or fewer residents (Peace and Holland, Reference Peace and Holland2001).

Managers who likened their home to a hotel emphasised the customer service orientation they tried to instil in their staff. This was expressed, for example, by emulating ‘hotel-style’ practices, such as presenting the dining room as a restaurant in which residents choose their meals from a menu. However, it was not always clear whether such renaming involved a genuine increase in choice. Meals, in practice, may not be much different from those in ‘family-like’ homes (Reimer and Keller, Reference Reimer and Keller2009). It also raises the question about potential trade-offs between the hotel-style practices of the home, with its more impersonal client–provider relationships, and the type of care provided and the intimacy it requires. This finding resonates with earlier concerns about consumerist versions of personalisation being built on a ‘flawed conception of the people who use social [work] services’ (Ferguson, Reference Ferguson2007: 400) that are at risks of underplaying the vulnerability and dependency of people in need of care (Fine and Glendinning, Reference Fine and Glendinning2005; Lloyd, Reference Lloyd2010; Lymbery, Reference Lymbery2010). Hotel-like ‘luxuries’ have also been perceived as less ‘homely’ and familiar (Cooney et al., Reference Cooney, Hunter, Murphy, Casey, Devane, Smyth, Dempsey, Murphy, Jordan and O'Shea2014; Wada et al., Reference Wada, Canham, Battersby, Sixsmith, Woolrych, Fang and Sixsmith2020). Yet perhaps the priority of ‘service’ over ‘care’ is precisely what attracts some people to these homes who value exclusivity and privacy over (forced) proximity, however justified (Bland, Reference Bland1999). However, it is not clear whether this type of home is suitable for all levels of need, such as people with advanced dementia, who may no longer be able to benefit from exercising their ‘client’ role. Again, it would be useful to investigate how care homes associated with this aspiration are experienced by staff, residents and their families. Perception of what is a suitable approach to personalisation may also change over time, as residents’ care needs increase.

We have included the ‘co-operative’ as a fourth, alternative type that brings together an emphasis of individual choice and autonomy, and close, perhaps more symmetric relationships between residents and carers, but also between residents themselves. While no manager spoke about his or her home as a ‘co-operative’, arrangements similar to this model can be found in the market for ‘extra care’ and assisted living in England which predominantly provides appropriate housing with elements of care, paid for separately, that can be scaled up as needed and organised according to people's preferences and needs (Evans et al., Reference Evans, Fear, Means and Vallelly2007; Vallelly and Manthorpe, Reference Vallelly and Manthorpe2009). Such arrangements shift decision-making power to residents, underpinned by financial and organisational provisions supporting the model. Similar models are also developed in other European countries, such as ‘senior flat-shares’ (Senioren-Wohngemeinschaft or Pflege-WG) in Germany, which are founded and owned by residents, who can organise their lives and care according to their preferences, while being financially supported by long-term care insurance (BMG, 2018).

The ‘co-operative’ also resonated with some managers’ account of having to square individual residents’ various, and sometimes conflicting, likes and dislikes, and having to manage behaviours of individual residents that impacted on other residents. In a ‘co-operative’, residents would decide together whether applicants would be allowed to join the community. However, in the care homes, this was not seen as realistic and none of the managers suggested that this was a practice they pursued. Instead, it was usually the manager who decided whether an aspiring resident was ‘a good fit’ based on whether the care home was able to meet his or her care needs. It is also not clear whether such arrangements necessarily result in residents experiencing close relationships or more control over their daily lives compared to other forms of residential care (Callaghan and Towers, Reference Callaghan and Towers2014). For example, a recent study from Finland found that people in assisted living felt lonely and imprisoned, suggesting that the concept may be better suited to meet some people's needs than others (Jansson et al., Reference Jansson, Karisto and Pitkälä2021). Yet the ‘co-operative’ may also include other forms of assisted living together that are not well represented in current housing and care delivery.

In contrast to earlier work by Davies (Reference Davies, Nolan, Lundh, Grant and Keady2003) and Trigg (Reference Trigg2018), this typology distinguishes two ‘relationship-centred’ models of residential care. The ‘family’ and ‘co-operative’ both underline the importance of personal relationships and caring, as opposed to providing services. However, they differ in their articulation of choice and individuality, with the family-type home aiming for a more collectivist model of care than the ‘co-operative’, with the former likely to be more successful in meeting the needs of people with advanced dementia and in preventing loneliness (Falk et al., Reference Falk, Wijk, Persson and Falk2012; Cooney et al., Reference Cooney, Hunter, Murphy, Casey, Devane, Smyth, Dempsey, Murphy, Jordan and O'Shea2014).

This typology is not intended to classify individual care homes, and it is unlikely that any care home, as portrayed by its manager, would fall entirely into any one category. Arguably, all care homes have elements of an ‘institution’ simply because they are a form of collective provision of care in a regulated welfare sector under resource constraint, a trait that seems perhaps more pronounced in some homes than in others (e.g. those caring for people with substantial nursing needs leaning towards similarities with hospital care) but is essentially irreducible. Instead, the typology aims to develop a better understanding of the tensions between different meanings of personalisation and the choices care home managers make in providing personalised care in the context of a communal setting.

This study has limitations. While we applied a number of criteria for sampling care home managers for interview, managers of nursing homes and with a nursing background were overrepresented in our sample, while managers of homes belonging to large chains were slightly underrepresented. Perhaps more importantly, managers were recruited through the ENRICH network and volunteered to be interviewed, both likely to be associated with high motivation and performance, although CQC ratings were mixed (with six ‘requiring improvement’). We have not interviewed older people residing in care homes directly for this study, as we focused on understanding managers’ conceptualisations of personalised care; however, future research should investigate how residents experience differences in the conceptualisation and provision of personalised care. Within the scope of this study, we also did not consider the constraints and effects of the physical environment (e.g. architectural features) on the personalisation efforts of managers, although space constraints were occasionally mentioned in interviews, and deserve to be investigated in their own right (Eijkelenboom et al., Reference Eijkelenboom, Verbeek, Felix and Van Hoof2017; Wada et al., Reference Wada, Canham, Battersby, Sixsmith, Woolrych, Fang and Sixsmith2020).

Does the existence of different types of personalised care pose a problem that needs to be addressed? In principle, variation in models enhances choice if people are able to select the kind of home that best reflects their preferences, personalities and needs, mediated by any cultural expectations prevalent in their environment (Hauge and Heggen, Reference Hauge and Heggen2008; Ågotnes and Øye, Reference Ågotnes and Øye2018). However, in England, there is substantial variation in the quality and availability of care homes between local areas, with many care homes that cater for those dependent on local authority funding being financially fragile following years of austerity. Availability of choice is also dependent on people's ability to pay; people on low incomes and with few savings and no relatives able to contribute to the costs of their care have their choice limited to care homes that accept local authority rates. In terms of policy, there seems to be an expectation, implicit or otherwise, that care homes provide both types of personalisation simultaneously, ideally at no additional cost: person-centred care with its emphasis on caring relationships and customer choice and decision-making along the lines of the consumerist model. This paper has attempted to bring the tensions between these concepts to the surface and to highlight the implications for residents and their families, as well as staff and managers of care homes. In years to come, debates about the future of adult social care funding should include consideration of the types of care homes we as a society would like to see in the care home market, to provide care, as well as a home, for older people in need of support.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Clinical Research Network leads for their help in the recruitment of care homes and to the care home managers who kindly agreed to be interviewed for this study. We also wish to acknowledge the valuable comments received from the participants of a workshop we held in November 2019 to discuss our findings.

Author contribution

All authors contributed to the conception, design, analysis and interpretation of the data. SE drafted the paper and all other authors revised it. All authors approved the version to be published.

Financial support

This work was supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Policy Research Programme through its core support to the Policy Innovation Research Unit (project number PR-PRU-102-0001). The views expressed are those of the authors and are not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

Ethical approval for this study was granted by the Research Ethics Committee of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM Ethics reference number 14727).