The Olympic Movement has been self-regulated from the beginning, and its private ordering is governed by the domestic law of the nations in which its organizations are domiciled and operate. Nevertheless, it is also an institution of global governance, with important ties to international law. This essay examines the nature of those ties and the push for additional alignment between the norms of the Movement and international legal norms. I first provide a taxonomy of Olympic Movement organizations, centered on the attributes that are helpful to understanding the place of each in the global governance of sport and the value the organizations produce for their diverse stakeholders. I then describe demands from international law for additional alignment with human rights and governance norms and the standard response from sport. In the final section, I argue that regulatory autonomy is necessary for sport to produce the values expected by its stakeholders; domestic law, including as it reflects international law, is generally an adequate check on abuses of that autonomy. International norms are useful not as binding law that would displace the Movement's autonomy, but as pressure for Movement organizations to consider aligning their policies and procedures with the public interests those norms reflect.

A Taxonomy of Olympic Movement Organizations

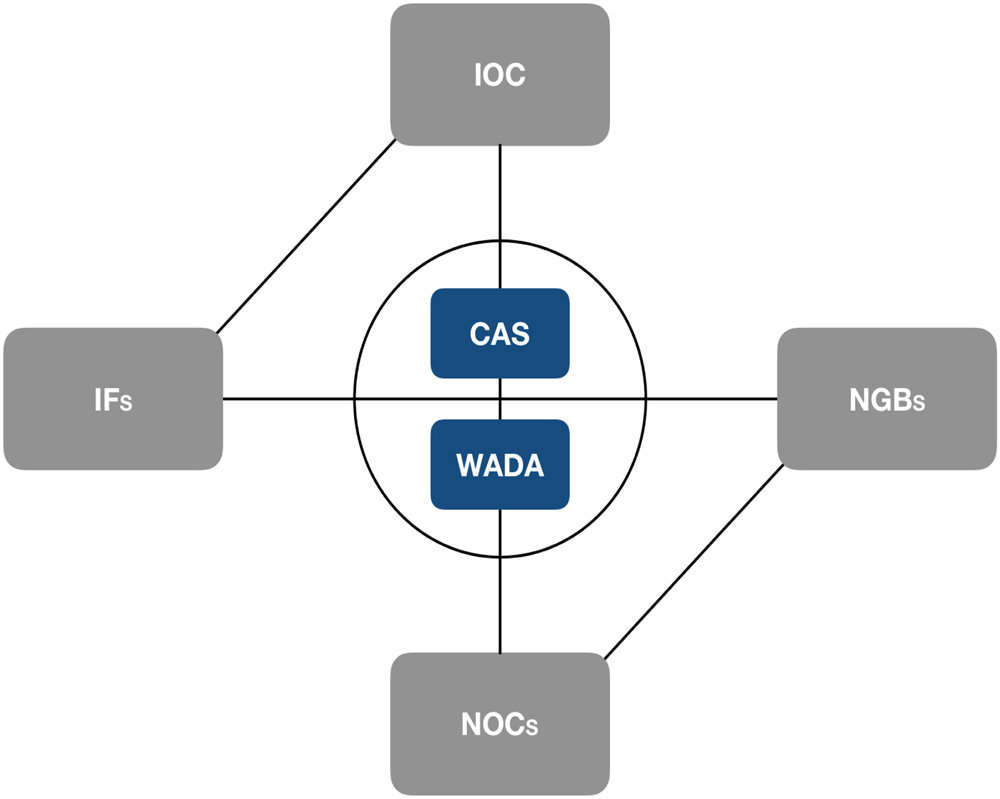

As represented in the figure below, the Olympic Movement is comprised of a set of closely-affiliated domestic and international organizations that, per the Olympic Charter and related instruments, regulate almost all aspects of international competitive sport.Footnote 1

The International Olympic Committee (IOC) is the nominal head of the Movement. It established, and since 1896 has continually owned and operated, the modern Olympic Games. The National Olympic Committees (NOCs) represent the IOC within their domestic spheres. They operate either simply to field their Olympic teams each quadrennial, or more generally as national sports ministries.

The International Federations (IFs) regulate their sports in the global arena which includes describing their attributes and events, setting their competition rules, and operating regional and world championships. Their domestic counterparts are the National Governing Bodies (NGBs). The Fédération Internationale de Football (FIFA) and U.S. Soccer are an example of an IF-NGB pair.

In an Olympic Year, the National Olympic Committees typically field their countries’ teams from NGB rosters; and the IFs work closely with the IOC to staff and manage their events at the Games consistent with IF regulations and IOC policy. In non-Olympic years, the IFs and NGBs operate independently of the IOC and NOCs, although the former often have important ongoing financial and regulatory ties to the latter.

The World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) and the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS) are linked to the other organizations through their specialized institutional missions. WADA is responsible for maintaining the Anti-Doping Code, sanctioning Olympic Laboratories, and investigating Code violations. CAS provides a forum for sports-specific dispute resolution, hearing cases of first impression and on appeal.

Olympic Movement organizations may be private, public, or quasi-public. The IOC and FIFA are examples of private entities, as are WADA and CAS. The French national sports federations are examples of public entities, and the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Committee is an example of a quasi-public entity. Because national governments tend to be interested in the organizations that regulate their teams and affect their prospects, those with the resources tend also to be financially invested. Thus, even where they are organized as private entities, the organizations’ operations are often tied to the public purse.

Regulatory Governance of Olympic Movement Organizations

Olympic Movement organizations are self-regulated and otherwise privately ordered according to the domestic law of the countries in which they have chosen to be domiciled and operate. The Olympic Charter requires the IOC and the International Federations to have significant regulatory autonomy, which is designed to be passed on to National Olympic Committees and National Governing Bodies. Disputes between organizations, e.g., between the IOC and WADA, and between organizations and their athletes, e.g., between FIFA and a player, are mostly handled internally through arbitration at the CAS. Appeals from CAS decisions are to the Swiss Federal Tribunal.

International law binds the organizations to the extent that it is part of domestic law. International legal norms are also influential, albeit informally. Most operational heads and their staffs are European and tend to be politically and culturally aligned with the human rights norms long embraced by their countries. That alignment creates an internal culture where those norms can thrive. From without, pressure from government audits and American or European-based sponsors also expressing international human rights and governance norms can bring significant pressure to bear on the Movement's substantive commitments and operational standards.

Olympic Movement organizations have four functions which correspond to the global value they produce. The first is health and welfare related: the promotion of sport as a good unto itself—as a means of healthy physical engagement and competition. The second is political: regional glory or to showcase the relative supremacy of a team and by extension of a people and their political system; diplomatic ends, including to provide a setting where otherwise disengaged or even warring parties can meet on neutral ground; and social change, to persuade stakeholders to adopt institutional commitments. The third is commercial: because the enterprise is largely self-funded but also sometimes simply for profit, the monetization of the brands and events. The fourth is regulatory: management of the system that achieves the three substantive ends. In all four respects, the Olympic Movement produces significant value for its stakeholders and their societies.

The Challenge from International Law and the Standard Response from Sport

Because this value may be produced in collaboration with public authorities using collective resources, and because Olympic Movement organizations have not always been good stewards of those resources, they are the focus of sustained examination and critique. Recurring targets are corruption in connection with mega-event site selection and the anti-doping effort, misuse and contested allocations of funds, human rights issues that arise in connection with events and eligibility rules, and top-heavy approaches to management and rule-making. Some of these issues have been tackled through internally-generated reforms and external pressure from domestic law, but, increasingly, pressure has come from academics, advocates, and institutions for additional alignment with international legal norms.

This last effort has mostly focused on the Movement's international organizations, and on the following three claims: The first is that they are proper subjects of international law however they are described, i.e., as public or quasi-public entities, as private multinationals, or as institutions of global governance. The second is that they are bound to the domestic law of the countries in which they are domiciled and operate, including to their treaty obligations. The third is that they should voluntarily follow other international legal norms, such as governance norms and the Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (Guiding Principles).

Compliance with international legal norms according to these claims can both support and complicate the Olympic Movement's socially valuable objectives and functions. A useful illustration is the matter of the eligibility rule for the women's category. In the remainder of this section I describe that rule, the challenge from international law, and the standard response from sport.

The raison d’être for the women's category is to provide a space in which females can compete against each other and not also against males. Sex segregation in this context is lawful according to standard commitments to sex equality and to the use of affirmative actions to secure those commitments. Specifically, because there is a significant performance gap between males and females which results from male reproductive sex traits, if sport were not segregated by sex, we would never see females in finals, on the podium, or in championship positions. Because most Olympic Movement organizations are committed to sex equality—at least to three podium spots for male athletes and three for female athletes—consistent with this grounding, they define eligibility for the women's category on the basis of those biological traits.Footnote 2

In the past decade, however, the Olympic Movement has been encouraged to re-define eligibility according to gender identity and legal sex instead, with the goal of including athletes who have the operative constellation of male sex traits in the women's category when they identify or are legally identified as women. This includes trans women and males with certain differences of sex development who were assigned female at birth. Notwithstanding its effects on the Movement's ability to meet its sex equality goals, the current push is specifically for unconditional inclusion—i.e., no physical or physiological conditions precedent to eligibility. Increasingly, this effort is grounded in a set of claims about what international law requires. For example, the following arguments and evidence were developed specifically to support the case brought before the CAS by Caster Semenya and Athletics South Africa against the International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF), now called World Athletics:Footnote 3

– A report authored by three UN Special Rapporteurs adopting the argument developed by intersex advocates that the IAAF, a private entity domiciled in Monaco, was subject—directly, not through Monegasque law—to provisions in conventions on health, torture, and discrimination; and further, that its eligibility rule, centered as it is on sex, not identity, violates their terms.

– Expert testimony to the effect that the IAAF's data collection, rule-making, and administrative processes, along with its eligibility rule, violate global governance norms pertaining to transparency and accountability, and human rights norms in violation of the Guiding Principles. The focus of the latter was on emerging norms about the treatment of people with differences of sex development, including their right to be classified on the basis of gender or legal identity without regard to sex or sex-linked traits.

– Resolutions of the Human Rights Council and the World Medical Association requested by the Republic of South Africa holding that the IAAF's sex-based eligibility rule violates norms of international law and medicine pertaining to the treatment of women and individuals with differences of sex development. The Council has since issued a report calling on sport regulators and domestic lawmakers to abandon sex-linked eligibility rules; this was, in effect, a call to abandon the commitment to sex equality in competitive sport.

The IAAF's response was grounded in its regulatory authority and obligations under the Olympic Charter to define its commitments and develop its rules consistent with applicable domestic law. Thus, it affirmed its right and responsibility to ensure that male and female athletes have matching competitive opportunities; that physical and physiological conditions on eligibility are subject to the informed consent process; and that due process requirements are met, including that its policies and their applications are reviewable by the CAS and then by the Swiss Federal Tribunal for conformity with clearly established procedural and substantive law. In the process, the IAAF took the position that it was in full compliance with Swiss and Monegasque law as both countries have committed to the Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, and the Conventions on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women and on the Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards. Implicit in this response was a rejection of the authority of the special rapporteur procedure and the Human Rights Council to render dispositive interpretations of its legal obligations and ultimately to modify its institutional commitments. Other Olympic Movement organizations tend to respond to the challenge from international law—on these facts and in general—consistently.Footnote 4

Olympic Movement Authority and International Law Norms: A Reconciliation

To produce the social goods embraced by stakeholders, including by nations around the globe, the Movement requires harmonization of sports-specific rules together with stakeholder buy-in, or at least the consent of the governed and full compliance. Given the nature and diversity of its objectives and functions and the degree of stakeholder heterogeneity, self-regulation and private ordering are most likely to secure these ends. Thus, as the IAAF did in the Semenya case, the organizations should stand by their regulatory autonomy; and they should examine critically any non-binding international law to ensure that it supports rather than undermines their objectives and functions.

As I note above, this approach nevertheless yields substantial alignment with international legal norms. True to their primarily European and American anchors, the Olympic Movement organizations have tended to self-regulate consistent with these political cultures, which have also had an outsized influence on the development of international law. Moreover, when the organizations’ rules and operations deviate from international norms, these can often be enforced via domestic law and, in Europe, ultimately by the European Courts of Justice and Human Rights.

It is only when international law norms aren't part of domestic law—or, in the case of European nations, recognized by European courts—that they are implemented only as organizational choices not mandates. On balance, this is good for the same reasons self-regulation and private ordering should be preferred in the first instance, i.e., given the multidimensional complexity of the Movement's project, it's the best way to secure the value that stakeholders and societies embrace. Organizations may decline to abide by non-binding norms and interpretations of norms for one of two reasons: Either they are insular for insularity's sake, e.g., because their top-heavy management enjoys power, or they understand that those norms and interpretations are in fact incompatible with their project. Their authority can and should be checked in the former instance but not in the latter.

Governance norms and the Guiding Principles are by design the product of deliberative process and typically reflect broad and deep consensus. Thus, even where they aren't binding, Olympic Movement organizations should generally abide by their terms since this will normally align with and thus support rather than complicate their mission. To say this is just a start, however; it doesn't resolve what it means to abide, how to proceed in the face of inconsistent commitments, and perhaps most importantly, who decides. The eligibility rule for the women's category is again illustrative.

Olympic Movement organizations begin from the twin premises that sex equality is undoubtedly an “internationally recognized human right”Footnote 5 and the affirmative actions necessary to give that right meaning in this specialized space—separate and equal events for males and females—are undoubtedly acceptable, as are closely-tailored, proportionate sorting criteria.Footnote 6 Because separate sex sport has created important value for the Movement, including in its health and welfare, political, and commercial functions, it is understood to be integral to the project and a first line commitment.

Given this, claims from international law about different, non-binding human rights priorities and related governance processes may but need not be considered if they would be undermining. Thus, for example, process claims that sound in transparency and accountability and go to ensuring the eligibility rule is evidence-based should be considered because stakeholders share that interest. In contrast, process claims that are, in effect, for a seat at the table for non-stakeholders whose interest lies in using sport as a vehicle for incompatible ends—e.g., the redefinition of sex or the elimination of affirmative sex classifications—can be rejected.

Institutions within international law, such as the Human Rights Council and UN Special Rapporteurs, may use their authority to reinterpret existing human rights or to affirm new ones. But where emerging rights and interpretations collide with established ones, or where the generative process is itself flawed or doesn't reflect broad and deep consensus, on the principle of consent of the governed it isn't wrong for Movement organizations to continue to abide by their own, otherwise lawful commitments.

Governance norms, new interpretations of existing obligations, and emerging rights, may become codified in binding law, which would force revolutionary change in the Olympic Movement's commitments along with the nature of the value it produces. To use the running illustration one last time, sport and sex equality are both important, but they too are policy choices and different institutions and values may prevail. Although the Semenya case was recently resolved by the Swiss Federal Tribunal in favor of the IAAF's eligibility rule,Footnote 7 it may ultimately pass through the European Court of Human Rights and trigger such revolutionary change as it concerns sport's commitment to sex-based affirmative action.

Whatever happens in that instance, Olympic Movement organizations should consider non-binding international law as useful pressure continually to review their commitments and procedures to ensure they remain in synch not only with stakeholder interests but also with the public good. Where there is a disconnect and it is clear that non-binding law has come to reflect broad and deep consensus, the organizations should adjust accordingly. The enterprise undoubtedly tilts private in its organizational forms and activities, but important public veins run through it and the externalities it produces are not insignificant. The Movement is most likely to thrive when, in the exercise of their governance autonomy, its organizations make choices consistent with that consensus.