In the early weeks of 1649, an iconographic revolution took place at the heart of English law and government. The execution of King Charles i on 30 January was swiftly followed by the abolition of the monarchy and House of Lords, as the portion of the Commons left in place following Colonel Pride’s purge declared themselves sufficient to govern for the nation. An urgent priority for Parliament was to establish its legal identity, as a justification of its exclusive right to rule but also in terms of the practical tools and routines that enabled the state to function. Central to this campaign was the creation of a new Great Seal of England, the instrument under which so much business was transacted.

Since the days of Edward the Confessor, the Great Seal had circulated the image of the monarch as fount of justice and protector of the realm throughout the Crown administration and into every part of the king’s dominions. Its iconography had grown more elaborate over the centuries, evolving from a symbol of monarchical power during the middle ages to become a lifelike characterisation of kings and queens under the Tudors. The reverse of Charles i’s Great Seal pictured him on horseback, conveying allegorical messages about royalty while also capturing the passion for hunting that punctuated the rhythm of the early Stuart court. Both these characteristics of the Great Seal, its representation of the power of the Crown and its recognisable depiction of individual occupants of the throne, posed a challenge to a post-regicidal regime seeking to stamp its own authority on the realm and to purge the memory of its royal predecessors.

Tasked with devising a new Great Seal representing the English people as ‘the original of all just power’ and parliamentary government,Footnote 1 the authorities looked to the interior of the House of Commons itself: namely, the former upper chapel of St Stephen in the Palace of Westminster, which since Edward vi’s reign had served as the meeting place of the elected burgesses and knights of the shire and was now the exclusive home of Parliament. The result was the first Great Seal of the Commonwealth, engraved by Thomas Simon in early 1649 and re-issued in an improved version in 1651 (figs 1 and 2). Following the instructions given to him, but also responding to printed images of the chamber, Simon captured the House of Commons in the act of debate: many legislators where there had been one monarch. Coupled with a detailed map of England, Wales and Ireland, this image of the Commons turned the Great Seal into a potent public symbol of the Commonwealth, encompassing both its constitutional and its territorial claims. This substitution of centuries-old images of royal authority stands comparison to other acts of royal iconoclasm following Charles i’s execution, and was accompanied by ceremonies performed in the Commons chamber that consciously undermined and replaced older traditions of royal ritual in Parliament. As an image of power and a representation of its physical location (the two being intimately connected), the republican Great Seal thus repays close attention.

Fig 1. Thomas Simon (engraver), second Great Seal of the Commonwealth (1651), obverse, map of England, Wales and Ireland. Photograph: seal impression, courtesy of the Society of Antiquaries of London, LDSAL A32.

Fig 2. Thomas Simon (engraver), second Great Seal of the Commonwealth (1651), reverse, House of Commons in session. Photograph: seal impression, courtesy of the Society of Antiquaries of London, LDSAL A32.

This article presents research conducted by the ‘St Stephen’s Chapel, Westminster’ Arts and Humanities Research Council-funded project at the University of York, led by the History and History of Art departments in collaboration with the UK Parliament, and additionally calls on the collections and expertise of the Society of Antiquaries of London.Footnote 2 The museum collection of the Society of Antiquaries preserves a cast of the second Commonwealth Great Seal of 1651, newly-commissioned photographs of which accompany this article. The probably nineteenth-century cast lacks provenance but is of high quality, enabling a remarkable level of detail to be made out in both the obverse or front of the seal, with its map of England and Ireland and the seas surrounding them, and the reverse depicting the Commons in session.Footnote 3 This article is also indebted to earlier generations of antiquarian research, notably that of engraver to the Society George Vertue FSA in his Medals, Coins, Great Seals and other Works of Thomas Simon, and also to Allan Wyon FSA in his spirited but still valuable The Great Seals of England.Footnote 4 The fact that several of the actors in the drama surrounding the Great Seal were themselves antiquaries, including both the polemicist who argued for its control by Parliament and the lord keeper who yielded custody of the Great Seal to the king at a critical moment, will hopefully add interest for readers of this journal.

THE GREAT SEAL: HISTORY, FUNCTION AND ICONOGRAPHY

Historians are shyer than they once were about using seals as source material. Valuable work continues to be done, for instance Margaret Aston’s exploration of episcopal seals, John Cherry’s study of late-medieval guild and fraternity seals (often the sole surviving object among those once owned by a pre-Reformation guild) or the interdisciplinary ‘Imprint’ project using forensic science techniques to investigate hand-prints in medieval seal impressions.Footnote 5 Otherwise the field is comparatively under-explored by the current generation of historians; deterred by the inadequacy of modern scholarly catalogues, and perhaps also uncertain about venturing into territory with unfamiliar technical conventions.Footnote 6 This is a pity, because the study of seals in terms of their manufacture, usage and iconography has the potential to enrich the writing of mainstream political and religious history as well as more specialist administrative, legal or antiquarian endeavours. In the case of the Commonwealth Great Seal, the relevant interpretative contexts are twofold: a visual history of representations of royal and parliamentary power dating back to the Reformation era, helping us to understand its radical design; and the architectural and political culture of the Palace of Westminster since the conversion of St Stephen’s Chapel to become the first permanent and dedicated House of Commons. Prints and engravings play a part in this story, but so too do parliamentary ceremony and the self-perception of the members who gathered in the Commons chamber.Footnote 7

As the highest form of authorisation under English law, the Great Seal was intimately associated with monarchy. By ancient custom the seal was vested in the lord chancellor, who as keeper of the king’s conscience represented the legal identity of the sovereign. In 1562 the Lord Keeper Act raised the status of the lord keeper of the Great Seal to ‘like place, pre-eminence, jurisdiction’ with the lord chancellor.Footnote 8 Located in the Chancery and serviced by officers with evocative names, including the spigurnal, the chafewax and the keeper of the hanaper, the Great Seal was employed to validate a range of documents, including charters, writs, letters patent and other kinds of royal grant. By the 1530s it had also become incorporated into the work of Star Chamber.Footnote 9

Geoffrey Elton’s survey of the sixteenth-century English constitution distinguished between bureaucratic processes, in which the Great Seal (with the other two royal seals, the Privy Seal and the Signet) continued to play an active part, and government itself, over which the seals and their offices had lost the influence that they once enjoyed. Whatever the truth of this, Elton’s conclusion that ‘in the main the day of seals was past’ does not take account of the potency of the Great Seal as a visual and physical representation of power; a quality that both Crown and Parliament understood very well.Footnote 10 Elizabeth i took a keen interest in her Great Seal, delivering the silver matrix into the custody of senior courtiers with her own hands and repeatedly reviewing patterns and wax models of a new design by Nicholas Hilliard during the final decade of her reign.Footnote 11 The physical handling of seals, and their ritual and material history (for instance the purses and chests in which they were kept), could usefully be factored into discussion of images of monarchy and the king’s or queen’s ‘two bodies’, natural and politic. When Queen Elizabeth went in procession from Westminster Abbey to open Parliament, she was preceded by the Great Seal: as David Dean puts it, ‘the ultimate symbol of the right to make law’.Footnote 12 The ceremonial destruction of a seal matrix following the death of a monarch marked the arrival of a new regime, as when James vi/i good-humouredly took a hammer to Elizabeth’s last Great Seal at Hampton Court in July 1603 before his own seal combining England and Scotland was unveiled.Footnote 13 Henry viii’s initial use of his father’s Great Seal, by contrast, betokened the continuity of early Tudor rule.

Since before the Norman Conquest the Great Seal has been double sided, offering complementary images of royal authority: the king or queen seated in majesty on the obverse, representing the monarch as fount of sovereignty and justice; and on horseback on the reverse, as protector of the realm. As early as the twelfth century, according to Elizabeth New, the engraving of a Great Seal often had ‘as much to do with politics and propaganda as practicality’.Footnote 14 Its value as a mechanism for royal magnificence has also been detected by historians of the early modern period, albeit more often as a footnote within broader discussions than as a subject in its own right. Dale Hoak, for instance, traces the imagery of a closed ‘imperial’ crown back to the 1470s and the third Great Seal of Edward iv.Footnote 15 Another leading exponent of Tudor royal iconography, Sydney Anglo, notes Henry viii’s decision to rework his father’s Great Seal in 1532 and again in 1541 (developments which Wyon plausibly links to the break from Rome and Henry’s assumption of the title of King of Ireland), while also pointing out that as senior a courtier as Stephen Gardiner was capable of mistaking its iconography for St George rather than King Henry.Footnote 16

As these examples demonstrate, the Great Seal adapted according to circumstance even if its essential elements remained the same. Kevin Sharpe draws attention to the novel design of Mary i’s Great Seal following her marriage to Philip of Spain in 1554, which balanced the need to grant Philip the deference due to a king of England without diminishing the sovereignty of the queen. Sharpe also notes the interplay between commemorative royal medals and seals under the Tudors, which we will encounter again in the work of the engraver Thomas Simon.Footnote 17

As an intrinsically royal object that was also vital to the procedures of early modern English law and administration, the Great Seal plainly held the greatest constitutional and representational significance. So long as governance was carried out in the name of the monarch (even if its structures were in practice mainly devolved), there was no contradiction between the two functions of the Great Seal. But when the broad consensus between Tudor Crown and Parliament faltered under the rule of Charles i, the two bodies – politic and natural – assumed to be embedded in the Great Seal also began to pull apart. As that conflict hardened into a military campaign and ultimately a constitutional revolution, the seal became a powerful weapon in what Sharpe has called the ‘battle for representation’ and ‘propaganda war’ between the king and Parliament; a struggle that would only become more intense in the aftermath of Charles’s execution.Footnote 18

RIVAL SEALS AND CIVIL WAR

In January 1642 Charles i left Windsor, bound initially for Dover and thence to York and Oxford. The ensuing stand-off between the king and Parliament meant that the role of lord keeper of the Great Seal, occupied by Sir Edward Littleton, became politicised as never before. Littleton had refused to apply the Great Seal to Charles’s proclamation for the arrest of the five members, but in an apparent change of heart he then released the seal to a messenger sent by the king and obeyed a summons to join Charles in York. The king’s successful reclamation of both the Great Seal and its keeper threatened the parliamentary administration with petrifying inertia. Efforts to pressure Littleton into returning the Great Seal to London were thwarted by Charles himself, who kept it safe in his bedchamber.Footnote 19 On 11 May 1643 the Commons resolved that ‘by reason of the Great Seal of England hath not attended the Parliament, according to the laws, the Commonwealth hath suffered many grievous mischiefs, tending to the destruction of the king, Parliament, and kingdom’; a replacement seal was therefore both just and necessary.Footnote 20 The deployment of a traditional language of commonwealth and monarchy in peril is revealing, another example of the legal fiction by which Parliament (assuming the authority of the Crown, or body politic) was able to levy arms against the body natural of the king.

At this stage, the controversy surrounding the Great Seal was a struggle for control over the royal image rather than an attempt to efface it. For MPs raised to revere the rule of monarchs and common law based on precedent, agreeing a new design for the seal was tantamount to imagining the king’s death: the ancient definition of treason. Even authorising a duplicate Great Seal was a step too far for some, potentially implicating the Commons in a different definition of high treason by forgery. As recounted by Sean Kelsey, the success of those MPs who argued that Parliament should acquire its own Great Seal further entrenched the factional divisions that were becoming apparent within the Commons.Footnote 21 Despite the reservations of many members, however, the lower house resolved to recreate their own version of the seal that the king had in his possession. On 19 July 1643 the former royal engraver Thomas Simon was duly offered £100 in hand to manufacture a Great Seal for Parliament.Footnote 22

The question of the Great Seal’s status was put and answered by the lawyer, pamphleteer and puritan William Prynne. In the 1630s Prynne had twice suffered physical mutilation on the orders of Star Chamber for supposed acts of sedition against the Crown.Footnote 23 His criticism of Charles i, whom he suspected of secretly commissioning the 1641 uprising of Catholics in Ireland, had by 1643 coalesced into his Soveraigne Power of Parliaments and Kingdomes, a lengthy justification of resistance to a king who ‘should bring in Forraigne forces … to destroy, or Conquer his Subjects, Parliament, Kingdome … and should join himselfe personally with them in such a service’.Footnote 24 Having dealt with the relationship between the king, Parliament and the people, Prynne turned his legal and polemical powers to the matter of the Great Seal. On 15 September the Commons ordered the printing of Prynne’s treatise The Opening of the Great Seale of England. His stated purpose was to refute the ‘over-rash censures of such who inveigh against the Parliament, for ordering a new Great Seale to be engraven, to supply the wilfull absence, defects, abuses of the old, unduely withdrawn and detained from them’.Footnote 25 Signing himself an ‘utter’ or outer barrister (as distinct from an ‘inner’ barrister, bencher or king’s counsel) of Lincoln’s Inn, Prynne drew on legal precedents mined from antiquarian sources to outline the evolution of the Great Seal’s high standing. He concluded that ‘This Seale is Clavis Regni; and therefore ought to be resident with the Parliament, (which is the representative body of the whole Kingdome) whiles it continues sitting; the King, as well as the Kingdome, being alwaies legally present in it during its Session’.Footnote 26

Prynne’s Opening of the Great Seale supplied the required evidence that custody of the seal properly lay with Parliament, without any diminution of its regal authority. The House of Lords was less keen on this course of action than the Commons, but eventually conceded to appointing keepers for the Great Seal on 10 November. Charles i predictably responded with a Declaration condemning Parliament’s action as an outright attack upon ‘the three most glorious jewels in our Diadem’: his ability to act, his enforcement of justice and his capacity to pardon and show mercy.Footnote 27 But as yet there was no intention to alter the royal iconography of the Great Seal; given Prynne’s line of reasoning, any attempt to negate the king’s image would have compromised Parliament’s essential claim that their seal superseded the version illegally retained by the king. For his own part, Charles was compelled to order a new seal for the Court of Wards bearing the regalia of the Prince of Wales, to differentiate it from ‘the old seal of the court kept and withheld from us’.Footnote 28

Thomas Simon, the maker of this 1643 Great Seal and the more radical Commonwealth versions that followed it, has been characterised as a natural supporter of Parliament on account of his French Protestant descent.Footnote 29 In fact he had previously enjoyed a career in royal service, and would go on to engrave seals and coins for Charles ii following his years of work for Commonwealth and Protectorate; a reminder that the makers of the images of power, in which early modern historians have invested such significance, could be perfectly willing to follow the money and turn their hands to any kind of representation, from royal to republican. Having served his apprenticeship under chief engraver of the royal mint Edward Greene, Simon would be proficient not only in the technical aspects of cutting matrices for medals and coins but also in the conventions of visualisation. Vertue credits him with ‘a most curious Great Seal for the Admiralty’ made in about 1636, when he would have been eighteen years old.Footnote 30 Otherwise Simon’s first recorded work, which propelled him into the growing political turmoil resulting from Charles i’s personal rule, was the medal struck to commemorate the 1639 Treaty of Berwick.

The obverse of Simon’s design depicts the king on horseback, a field marshal’s baton in his right hand, while his horse rears over a cuirass and abandoned military paraphernalia. Surrounded by contracted versions of his royal titles, the mounted king at once recalls the imagery of the royal Great Seal. However, Simon has set the figures in almost three-quarter pose to the surface, rather than adopting a more hieratic profile treatment. To attempt a successful impression of recession, along with the animated spirit that pervades the obverse, marks out Simon’s abilities at suggestive modelling. In contrast, the medal’s reverse indicates his familiarity with abstract heraldic forms. A rose for England and the Scottish thistle are bound together by a cord; the inscription ‘Quod Deus’ is a reference to scripture, ‘Whom God hath joined together let no man put asunder’.Footnote 31 By returning to Simon for the 1649 and 1651 Great Seals, the Commons ensured that they would be realised to a consistent aesthetic standard.

THE GREAT SEAL OF THE COMMONWEALTH

While King Charles i still lived, albeit under house arrest in various locations after his surrender to the Scots in 1646, a Great Seal bearing his image could still confer some degree of legitimacy over the deliberations and decisions of Parliament. But the king’s complicity in the second civil war reinforced his identification as a ‘man of blood’ in the eyes of the army, and on 6 December 1648 Colonel Thomas Pride purged the Commons of members still hoping for a negotiated settlement. With the stage set for Charles’s trial and execution, the Rump Parliament began creating a legal and administrative framework that would derive from their own corporate identity rather than the king’s.

The making of the first Great Seal of the Commonwealth is recorded in the Journals of the House of Commons, the initial step being the appointment of a committee on 6 January 1649 to ‘take order for the framing of a Great Seal’.Footnote 32 Two days earlier, the Commons had taken the unprecedented step of declaring ‘That whatsoever is enacted, or declared for law, by the Commons, in Parliament assembled, hath the force of law; and all the people of this nation are concluded thereby, although the consent and concurrence of King, or House of Peers, be not had thereunto’.Footnote 33 In effect the Commons had legitimised itself as the sole source of legal and political authority. The committee for the Great Seal was made up of nine members: Francis Allen, John Blakiston, William Lord Monson, John Fry, Nicholas Love, Gilbert Millington, William Purefoy, Thomas Scott and Henry Marten, to whom ‘the more particular care’ of the matter was delegated.Footnote 34 During the early sessions of the Long Parliament, Marten had been a vocal critic of the royal prerogative and a regular contributor to committees. Paul Seaward describes him as ‘one of the most influential and active of English politicians’ during the creation of the republic.Footnote 35 Marten’s philosophy has been summarised in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography as guided by the premise that ‘the representative must always be in direct balance with those it represented’, a notion which may well have steered the Great Seal’s design.Footnote 36 Another possible influence on the committee’s thinking was the range of counties and communities that they represented, from Dorset and Hampshire to Nottinghamshire and Newcastle – a geographical span made manifest in the annotated map of England replacing the enthroned king on the obverse of the Commonwealth Great Seal. All the men on the committee could be categorised as ‘regicides’, through their role in the high court of justice arraigned to try Charles i. Five would also sign the king’s death warrant.

Regrettably, the minutes of the Great Seal committee have not survived. After three days, however, Marten informed the Commons that a decision had been reached:

That a great Seal be graven, with the addition of the map of the Kingdom of Ireland, and of Jersey and Guernsey, together with the map of England; and, in some convenient place, on that side, the arms by which the Kingdoms of England and Ireland are differenced from other Kingdoms … That, on the map-side of the Great Seal, the inscription shall be, ‘The Great Seal of England, 1648’ … That the inscription on the other side of the Seal on which the sculpture of the House of Commons is engraven, shall be this; viz. ‘In the First Year of Freedom, by God’s Blessing restored, 1648’.Footnote 37

In order to realise this agreed design, on 26 January Thomas Simon was ‘authorized to engrave a Seal, according to the form formerly directed’ and granted £200 for materials and his fee.Footnote 38 The need to consolidate the Commons’ authority was pressing. On 8 February an Act was passed to establish the new Great Seal in place of the version of the royal seal that Parliament had been using since 1643. The defunct seal matrix was brought into the Commons chamber to be broken into pieces, which were given with the purse to its erstwhile keepers Bulstrode Whitelocke and Sir Thomas Widdrington in lieu of their fees.Footnote 39 Following the surrender of Oxford in 1646, the king’s own seals had been confiscated and brought to Parliament to be destroyed in the presence of the Lords and Commons. But coming so soon after Charles’s beheading, this second ritual dismemberment of his portrait on the Great Seal will have seemed all the more significant. Four new keepers were then sworn into office by Speaker William Lenthall – the same Speaker who in January 1642 had denied Charles i’s demand to give up the five members on grounds that he was the Commons’ servant, not the king’s, and was now in 1649 effectively ‘the leading citizen of England’.Footnote 40 Lenthall presented the keepers with Simon’s new Great Seal of the Commonwealth, whereupon they processed out of the chamber preceded by the serjeant at arms bearing the mace.Footnote 41 A ceremony of breaking and making the Great Seal traditionally focused on the sovereign had been co-opted by the House of Commons, with the Speaker substituting for the king. Watching and cheering from the benches, MPs offered their personal affirmation of a symbolic revolution. Within months the serjeant’s mace would similarly be reimagined along republican lines, supplied by London goldsmith Thomas Maundy to a design specified by another parliamentary committee.Footnote 42

The legal validity of the new seal was consolidated with an ordinance making any attempt to counterfeit it high treason.Footnote 43 This first Great Seal of the Commonwealth remained in use for more than two years, until an Act for its replacement – using the same combination of map on the obverse, and Commons chamber on the reverse – on 26 March 1651.Footnote 44 The need to re-make the seal has sometimes been understood as indicative of its inferior quality, given the haste with which Simon had been forced to work: less than two weeks between commissioning and delivery. An alternative explanation is that the matrices had become excessively worn through a deliberate policy of disseminating the seal throughout the republic, validating documents from the appointment of ambassadors and clergymen to grants of pardon for horse-thieving and witchcraft – thus a victim of its own success.Footnote 45

The second Commonwealth Great Seal was also executed by Thomas Simon. George Vertue refers to impressions of the seal taken by Simon himself, one of which Vertue engraved for his Works of Thomas Simon from the collection of his friend and patron Edward Harley, second Earl of Oxford. Taking their cue from Vertue, who praised the 1651 Great Seal as ‘the most curious and extraordinary work that was ever performed’, commentators have acknowledged its superiority to the 1649 original, though the elements are very similar. An updated legend, ‘IN. THE. THIRD. YEARE. OF. FREEDOME. BY. GODS. BLESSING. RESTORED’, and casement windows opened wide to bring some welcome air into the Commons chamber, enable the 1651 version to be distinguished from its predecessor.Footnote 46

The technical skill displayed in the second Great Seal is undoubtedly remarkable, in its intricacy of detail – for instance, the decorative sequence (perhaps tapestries) on the walls of the Commons chamber, unique evidence for this feature at this date – but also in its angle and depth of perspective, displaying a mastery of these accomplishments that the design of previous royal Great Seals had not demanded to the same degree. This stands in contrast to the conventional assessment of post-Reformation seals, whose aesthetic tenor has often been seen as a falling short of the achievements of late-medieval metalworkers. Simon retained his post of chief engraver as Commonwealth transitioned into Protectorate, supplying the replacement Great Seal ordered by Cromwell’s Council of State in 1655 in which the lord protector appeared on horseback; a version for Richard Cromwell followed.Footnote 47 But the parliamentary imagery of the 1651 Great Seal was then revived during the dying days of the Commonwealth, Simon applying a simplified legend, ‘GOD. WITH. US. 1659’ to his now familiar image of the Commons chamber. He understandably took advantage of this opportunity to renew his petition for money owed for his previous work, estimated at £1728 5s 8d in 1657.Footnote 48

The Great Seals of 1649, 1651 and 1659 transformed the iconography of the highest legal instrument in the land, replacing the medieval political theology of the king’s ‘two bodies’ with representations of Parliament and the territories over which it ruled.Footnote 49 On the obverse of the seal (see fig 1), maps of the two kingdoms (as they were still termed) of England and Ireland asserted a new vision of the body politic, defined territorially and divorced from the body natural of the monarch. The arms of England appear as a cross of St George on an oval shield, with a harp equivalent for Ireland. Names of towns, counties, seaports and principal headlands are picked out in tiny letters, perhaps copied from an atlas by the Dutch cartographer Joan Blaeu; according to Vertue ‘so distinctly expressed and named in such minute characters, as to make it a work truly admirable, and beyond compare’.Footnote 50 Numerous parliamentary boroughs are depicted, for example Helston in Cornwall and Boroughbridge in Yorkshire, in a visual endorsement of the Commons’ claim to represent the whole nation. But the imagery of the Great Seal is both less and more than this; neither a complete list of towns and counties returning members to Parliament, nor restricted to communities incorporated as parliamentary boroughs. Falmouth appears, barely a town by the mid-seventeenth century but a prized fortified haven on Cornwall’s south coast. Other ports and headlands feature prominently, from Carlingford Haven to Lizard Point, and indeed the map functions as a declaration of sovereignty over the seas as much as the land; an argument reinforced by the ships under sail, the compass dial and (more fancifully) a spouting dolphin.

Given the British context of the conflicts of the 1640s and 50s, the prominence given to Ireland in the composition requires some explanation. Ireland retained its own Parliament and indeed its own Great Seal, so this was not a representation of boroughs returning members to Westminster. Rather, the map on the Commonwealth Great Seal re-asserted a claim to English sovereignty over Ireland that had been bound up with monarchy since the twelfth century, was reinforced when Henry viii became king of Ireland in 1541 and had been vigorously and violently pursued by parliamentary commanders since the onset of the Irish rebellion of 1641. Kingship may now have been abolished, but England’s dominance over Ireland persisted nonetheless. The Great Seal thus demarcated the geographical jurisdiction of the Rump Parliament, including other territories – the Channel Islands, the Isle of Man – historically tied to England by virtue of the Crown.

The decision to represent the authority of the Commonwealth in a map suggests a responsiveness to the wider cultural interest in cartography observable in the visual arts since the later sixteenth century.Footnote 51 The depiction of the fleet of fighting ships and merchantmen, for instance, bears comparison with the emblematic title page that John Dee devised for his 1577 treatise promoting a maritime ‘British empire’, the Generall and Rare Memorials pertayning to the Perfect Arte of Navigation.Footnote 52 A more recent and specific example was the map on the seal matrix of the 1630 Providence Island Company, which sought to establish an English Puritan colony in the Caribbean.Footnote 53 Cartography and heraldry often went together in the early modern period, and so it was on the Commonwealth Great Seal. The arms of England and Ireland appear in their new and simplified formulation, voicing what Kelsey calls an ‘entirely new representational language’ that spread to ceremonial maces and naval flags, among other media.Footnote 54 But if the form of the arms was new, the continued use of heraldry also recognised the resonance of precedent: a fundamental quality for an essentially medieval tool of government re-worked to ensure the continuity of law and administration under the new regime.

The reverse of the Commonwealth Great Seal (see fig 2) was equally innovative, though here too there was an underlying appeal to the familiar. Centuries of equestrian royal imagery were replaced by a visualisation of the Commons in session as the wellspring of legitimate authority. Henry Marten’s reference to the ‘sculpture of the House of Commons’, in the sense of a picture or design derived from an engraved plate or a block (newly coined in the mid-seventeenth century), was apposite.Footnote 55 Closely related to engravings of the Commons chamber that had been in circulation since the 1620s, the image on the reverse of the Great Seal added relief and perspective to produce a three-dimensional picture of Parliament in the very act of debating and governing.

Surviving examples of the 1649 Great Seal tend to be poorly preserved, but in the more sharply detailed 1651 impression the skill displayed by engraver Thomas Simon is striking. The cast in the Society of Antiquaries collection reveals a wealth of architectural detail, from the leading of the windows overlooking the Thames to the joins in the wooden planking on the floor – features attested in State Paper and other manuscript evidence for the conversion of St Stephen’s Chapel into the Commons chamber.Footnote 56 But it is in the characterisation of the membership of the Commons, each of whom is an individual rather than a type, that the verisimilitude of the design finds its greatest expression. The man standing to speak has by custom removed his hat, grasped in his right hand while his left gestures across the chamber; his posture is suggestive of an actor on the stage. Some of his fellow MPs are looking at him, while others watch for reactions to his words on the opposite side of the chamber. The house is full of conversation, as neighbours address each other or turn around to talk to those behind them. A discussion between two men beyond the bar in the west end of the chamber seems particularly animated, just possibly because a speech from the front benches would have been difficult to hear from this position. Clerks of the parliaments bend over their papers, while a doorkeeper – perhaps the serjeant at arms – guards the entrance to the chamber. The Speaker (presumably William Lenthall) sits stiff-backed, his raised chair decorated with the classical columns specified in the accounts of the surveyor of the king’s works, but now shorn of the royal arms that had been updated as recently as 1645.Footnote 57

The ‘accuracy’ of an image like this must naturally be treated with caution. Yet from what we know of the Commons chamber in this period, culled from archival evidence as well as visual sources for the interior from the 1620s onwards, the Great Seal appears to be faithful not only to its architecture but also to how it functioned as a space, capturing its noise and intimacy and culture of performance. The depth of field achieved by Simon, for instance in the depiction of the clerks’ table, could have been studied from the life by means of the gallery installed in 1606; certainly the artist was familiar with the layout of the chamber. In only one detail did he materially alter the appearance of the House of Commons, and its politics are deeply significant. Until December 1648 about 470 MPs had been entitled to sit in the lower house, not much different from the number returned to the last Parliament of Elizabeth i. But Pride’s purge cut the Commons to less than half its size: some 211 MPs, and in practice many fewer than that during the critical weeks around the king’s execution.Footnote 58 A Commons chamber that had been crammed for generations, with space on the benches often impossible to find, was now uncharacteristically thinned out. Though the record does not specify, we may imagine Marten making it clear to Simon that the Rump should appear to be no less populated than previous parliaments had been.

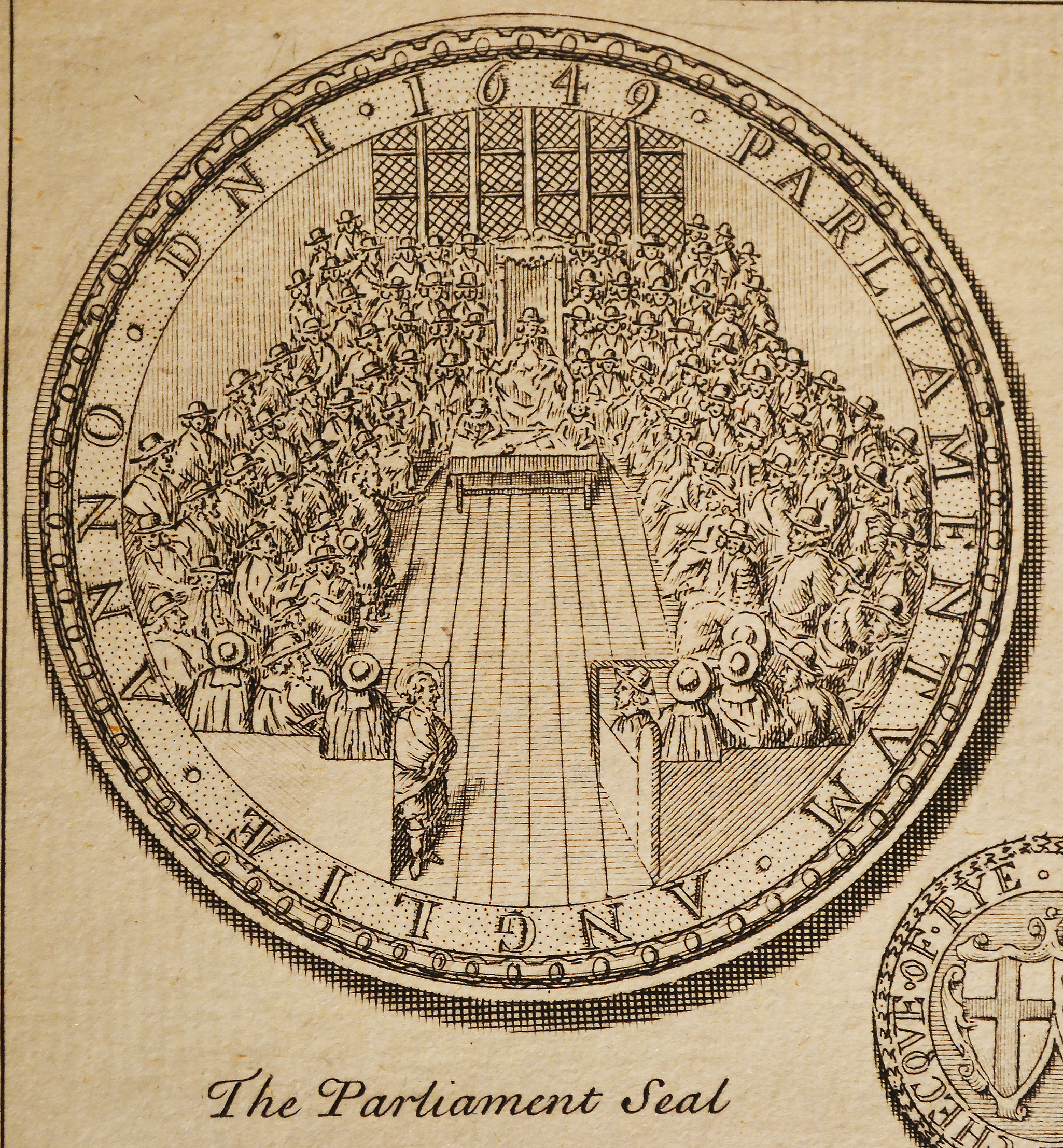

The Great Seal image of the House of Commons was reproduced in other Commonwealth-era seals, guaranteeing that it reached every part of the realm. Vertue’s Works of Thomas Simon includes descriptions and plates of the seals of the courts of Common Bench and Exchequer, the County Palatine of Lancaster and court of Common Pleas of the Duchy of Lancaster, all of which feature versions of the Commons chamber. Marten’s Great Seal committee was given responsibility for ensuring that any writs issuing from the Westminster courts antedating the change of style should be authorised under the old versions of the relevant seal. Parliament also had its own seal, again with the same view of the Commons interior but a different legend and style of dating, ‘PARLIAMENTUM. ANGLIAE. ANNO. D[OMI]NI. 1649’ (fig 3).Footnote 59 Simon additionally adapted his ‘sculpture’ of the House of Commons for use on two of the medals that he designed for the Commonwealth: the 1650 Dunbar medal, its obverse featuring a portrait of Oliver Cromwell that the artist travelled to Edinburgh to capture in the life, with the House of Commons appearing in the reverse of some versions; and a Naval Reward medal of the same year.Footnote 60

Fig 3. Thomas Simon (engraver), seal of the Parliament of England, 1649 (Vertue 1780, plate v).

ICONOGRAPHY AND ICONOCLASM

The act of denying the late king’s authority by effacing his image from the Great Seal needs to be understood as part of a wider programme of iconoclasm. The nullification of other symbols of monarchical power, in particular the royal arms, was made a priority by the Commonwealth. Statues of the king were removed from several ecclesiastical and commercial sites in London following examples of popular iconoclasm that had taken place during the war, such as the attack on Hubert Le Sueur’s bronzes of James i and Charles i that was reported from Winchester.Footnote 61 The most prominent target of this campaign would be the statue of Charles erected in 1629 to conclude the sequence of monarchs at the Royal Exchange. On 31 July 1650 the Council of State ordered the mayor and aldermen that the statue should be ‘demolished by haveing the head taken off and the Sceptre out of his hand, and this inscription to bee written Exit tyrannus Regum ultimus Anno primo restituæ Libertatis Angliæ 1648 [so passes the last tyrant, in the first year of the restored freedom of England 1648]’.Footnote 62

The inscription not only clarifies why such iconoclasm was politically necessary to demonstrate and validate the Commonwealth, but also parallels the sentiments written on the obverse of the Great Seal. Henry Marten’s stipulated legend, ‘In the first [or third] yeare of freedome by God’s blessing restored’, was a radical break with the past, presented in English rather than Latin and replacing the regnal dating that was synonymous with government by monarchy. Implicitly celebrating the execution of the king as the restoration of a lost state of freedom, the legend neatly frames the ideal of a representative body as the guarantor of ancient liberties that been negated during Charles’s personal rule, acting in accordance with the workings of divine providence.

The use of English on the Great Seal anticipated further changes to inherited procedures of documentation, which altered the linguistics and graphology of governance. By the seventeenth century, the courts and departments of the royal household based at Westminster (Chancery, King’s Remembrancer, Exchequer, Common Pleas, King’s Bench) had developed their own distinctive hands for the copying and writing of documents, serving as proof of legal worth. This plethora of conventions, mannered and remote from practical requirements, was abolished during the Commonwealth. In 1650 English was established as the sole language for domestic administration, a reform already heralded in the Great Seal’s inscription. Latin and departmental hands were to be abandoned, and records henceforth ‘written in an ordinary, usual, and legible hand and character’.Footnote 63 Legal phraseology was also updated to reflect parliamentary authority and efface any formulae that were redolent of monarchy.Footnote 64 The Great Seal serves, literally, as a sigillum of reforms to both the language and appearance of legal and administrative documents.

All of this took place while the late king’s posthumous identity was being shaped by the illicit circulation of the Eikon Basilike. A book of meditations and prayers that purported to be Charles’s reflections upon the turbulent events leading up to his execution, it presented its readers with a view into the private devotional world of the late king. The frontispiece to early editions, engraved by William Marshall, established an iconographic model for Charles as a suffering martyr. The king is shown renouncing an earthly crown or ‘vanitas’, to clutch a crown of thorns ‘gratia’, while looking upwards to a stellar crown ‘gloria’. Even as the king’s presence in administrative process and public monuments was being purged, his image was reaffirmed within the private sphere of the Eikon’s readership. Described by one historian as ‘the publishing sensation of the century’, with thirty-five editions in a single year, Eikon Basilike must have spurred on the republican authorities to erase the visual remnants of Charles’s legacy.Footnote 65 The creation of a new Great Seal, and the destruction of Charles i’s public iconography, were expressions of a unified ideological intent; the one affirming an image, the other erasing it.

The selection of the Commons chamber as an emblem for the republican Great Seal was a declaration of the collective authority vested in one institution. Converted from the former royal chapel of St Stephen at Westminster, the two-story ‘Parliament House’ was a landmark in the topography of Westminster, drawn and engraved by artists from Anthonis van den Wyngaerde in the 1540s to Wenceslaus Hollar a century later.Footnote 66 And yet the committee for the Commonwealth Great Seal chose to depict the interior of the Commons chamber with a debate in progress, rather than the chamber’s prominent east end. This selection of collective institution over architectural exterior responds to a wider association of the appearance of the Commons; one which had been consistently reinforced since the 1620s by popular print, and which finally returns us to the deliberations of Henry Marten and his fellow MPs who assembled to discuss the Great Seal’s design in 1649.

The summoning of Parliament in 1640 had seen a flurry of political pamphlets and tracts, several of which derived their frontispieces from images of Parliament (crown, Lords and Commons) last issued prior to Charles i’s personal rule. These prototypes were frequently amended to reflect the pressures for reform and redress of grievances in the climate of the day. Such reissuing and re-cutting of illustrative plates may at first have been the result of expediency by printers. But their cumulative effect was to impress upon a politically-attuned and literate readership ways of visualising the English state that emphasised the place of Parliament, and especially the House of Commons.

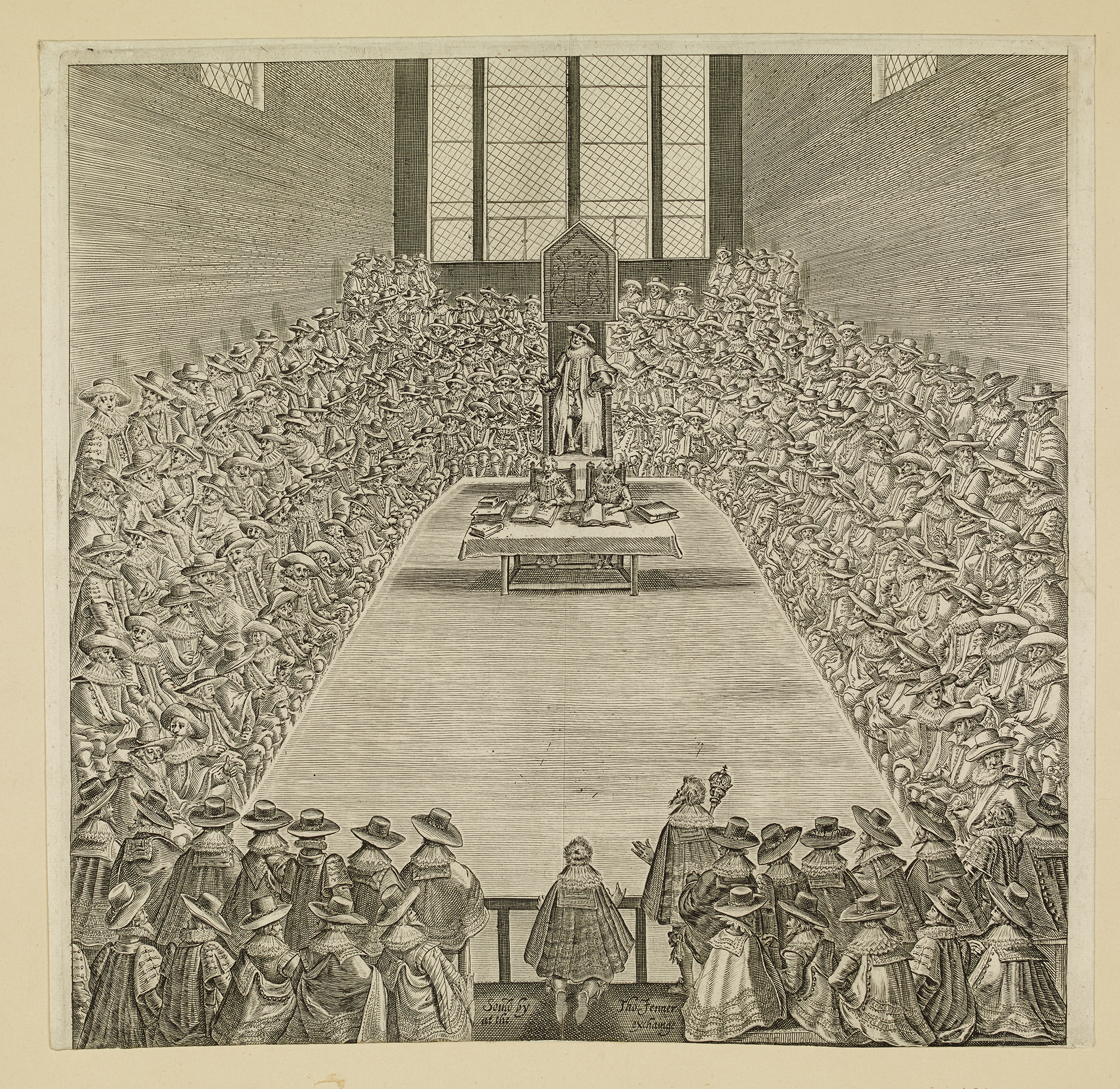

In support of this point, it is known that MPs themselves took an interest in such images. One significant example, collected by the parliamentary diarist Sir Simonds d’Ewes and formerly part of the Harley collection of manuscripts, is preserved in the British Museum (fig 4).Footnote 67 Issued in c 1624 and thus the earliest impression of the interior of the House of Commons that has so far been identified, the subject of the engraving and the fact of its collection both attest to the gathering self-awareness among MPs, and sense of association between place and institution, that historians of Parliament have detected in this period.Footnote 68 The features of the Commons highlighted by Simon in the Commonwealth Great Seal – the steeply raked seating, with two shorter additional tiers perched at the east end of the former chapel; the Speaker in his high-backed chair; two clerks consulting their books; above all, the packed and intimate atmosphere of the chamber – are all present in this print made some twenty-five years earlier. The perspective of the Great Seal image is foreshortened by comparison, and the seal has four tiers of seating rather than the five in the print (presumably to save space in what was already a crowded composition), but otherwise the similarity between the two images is immediately evident.

Fig 4. Unknown engraver, published by Thomas Jenner, ‘The House of Commons’, c 1624, print formerly in the collection of Sir Simonds d’Ewes. Image: BM 1850,0726.9, reproduced by kind permission of the British Museum © The Trustees of the British Museum.

An even closer relationship is observable in an anonymous print issued in 1641, entitled ‘Platform of the Lower House of this Present Parliament’ (fig 5).Footnote 69 The broadside format of the image, which at 760mm is more than twice the width of the engraving collected by d’Ewes, allows for a view of the Commons chamber in session to be juxtaposed with a map of the English and Welsh counties, simplified plans of towns and cities from Berwick to Launceston and Caernavon to Ely, a view of the city of London and a map of Westminster. The treatment may be crude by comparison with the high standards subsequently achieved by Thomas Simon, but the combination of the House of Commons in session and maps of English and Welsh boroughs returning members to Parliament invites the possibility that this image, or one like it, inspired the deliberations of the committee for the Great Seal in January 1649. Lords and bishops traditionally took precedence over the Commons in parliamentary ceremony and protocol, and indeed a letterpress ‘catalogue’ of peers and bishops entitled to be summoned to Parliament circumscribes the central image and surrounding maps. But it is a member of the Commons who heads that list, the same man who has removed his hat to address the chamber: Sir Edward Littleton, judge, antiquary and – as we have seen – lord keeper of the Great Seal. Littleton was appointed to this position in January 1641, just a month before his elevation to the Lords as Baron Littleton, helping us to date the print more precisely.Footnote 70

Fig 5. Unknown engraver, ‘Platform of the Lower House of this Present Parliament’, c 1641, broadside. Image: BM 1885,1114.124.1-3, reproduced by kind permission of the British Museum © The Trustees of the British Museum.

The title of the print is also worth reconsidering. ‘Platform’ in the mid-seventeenth century meant a raised surface on which people could stand, or more specifically a theatrical stage. Either definition might apply to a Commons chamber situated in the former upper chapel of St Stephen, where speech and ceremony were performed on a wooden floor elevated above foot level of the lowest tier of seats, as visible in this print. But another meaning was also current, as anyone with military experience would have appreciated: a platform was a structure on which artillery was mounted.Footnote 71 Taken in this sense, the ‘Platforme of the Lower House’ conveyed the barrage of voices, Littleton’s not least among them, that were defending the rights and privileges of the Commons.

The novelty of such an engagement between king and people unsurprisingly sparked interest elsewhere in Europe. A sequence of three prints in the British Museum, provisionally dated to 1641–50, pictures the constituent parts of the English Parliament translated for a French audience, including a view of the Commons interior probably derived from one of the English versions then in circulation (fig 6). ‘La maniere et ordre de la Sceance de la maison basse’ is more generic in its treatment of the architecture of the chamber than either of the two English prints discussed here. But its depiction of the membership of the Commons (as the title explains, made up of knights, gentlemen and burgesses), and details of the Speaker, clerks, bar and mace, fed a French market hungry for news of what was taking place across the Channel.Footnote 72 Companion prints presented the other two estates that joined with the Commons to constitute the English Parliament: the king enthroned with orb and sceptre, attended by ‘les seigneurs spirituelz et temporelz dans le hault parlement’ and a herald displaying the royal arms; and the convocations of Canterbury and York, bishops and clergy meeting in their separate houses of assembly.Footnote 73

Fig 6. Unknown engraver, ‘La maniere et ordre de la Sceance de la maison basse ou des com[m]unes qui consiste en chevaliers gentils hom[m]es et bourgeois’, c 1641–50, print. Image: BM 1847,1009.137, reproduced by kind permission of the British Museum © The Trustees of the British Museum.

In refashioning the Great Seal to proclaim the sovereignty of the Commons, Henry Marten and Thomas Simon deliberately drew on visual material with which a politically-engaged public would have been conversant, both within England and further afield. The House of Commons was a recognisable type of image that had appeared and re-appeared in support of the parliamentary cause. It was clearly felt to embody the authority of Parliament more effectively than a view of the chamber’s exterior would have done. As realised by Simon, the emblem of the Commons in session on the Great Seals of 1649, 1651 and 1659 had clear antecedents among popular prints in circulation since the 1620s; a medium familiar to members, their supporters beyond Parliament and royalist detractors alike.

CONCLUSION: PICTURING PARLIAMENT

The supremacy of the Commons made manifest in the Great Seal of the Commonwealth may have been newly asserted, but it had been long in the making. Its lineage ran past the Elizabethan ‘monarchical republic’ identified by Patrick Collinson and back to the innovations of the earlier Tudor period: the parliamentary Reformation of 1529–36, the move into St Stephen’s Chapel in Edward vi’s reign and the assembling of a formal Commons archive. According to Sean Kelsey, in its creation of a public image the Commonwealth was essentially conservative and improvisatory, ‘the embodiment of a “gentry republic” which had always provided the bare bones of a structure of authority over which was draped the surface gilding of early modern monarchy’.Footnote 74 If the revolutionary iconography of the republican Great Seal did not announce the truly radical new regime that some outside the Commons were agitating for, then this was consistent with what Blair Worden has described as the ‘trail of disillusionment and resentment among the advocates of social and religious reform’ left by the Commonwealth.Footnote 75 The simple fact of the Great Seal’s continued existence, with its centuries of history and embedded procedures and fees, argues for the limitations of the legal reforms attempted by the Rump Parliament. Radical in design, the Commonwealth Great Seal at the same time signalled an underlying continuity in law and government: revolution in the pre-Enlightenment sense of a turning back to a pre-existing state of affairs, in this case the primacy of a House of Commons that (in the perception of members, at least) could be dated back a century and more. So it was that the image of the Commons chamber, already familiar from pamphlets and engravings, acted to reassure office-holders in the localities and other recipients of the Great Seal that not all the world had been turned upside down.

ABBREVIATIONS AND BIBLIOGRAPHY

Abbreviations

- BM

British Museum

- ODNB

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

- OED

Oxford English Dictionary

- TNA

The National Archives, Kew